Fandom

A fandom is a subculture composed of fans characterized by a feeling of camaraderie with others who share a common interest. Fans typically are interested in even minor details of the objects of their fandom and spend a significant portion of their time and energy involved with their interest, often as a part of a social network with particular practices, differentiating fandom-affiliated people from those with only a casual interest.

A fandom can grow around any area of human interest or activity. The subject of fan interest can be narrowly defined, focused on something like a franchise or an individual celebrity, or encompassing entire hobbies, genres or fashions. While it is now used to apply to groups of people fascinated with any subject, the term has its roots in those with an enthusiastic appreciation for sports. Merriam-Webster's dictionary traces the usage of the term back as far as 1903.[1]

Many fandoms are overlapped. There are a number of large conventions that cater to fandom such as film, comics, anime, television shows, cosplay, and the opportunity to buy and sell related merchandise. Annual conventions such as Comic Con International, Wondercon, Dragon Con, and New York Comic Con are some of the more well-known and highly attended events that cater to overlapping fandoms.

Origins of fandom

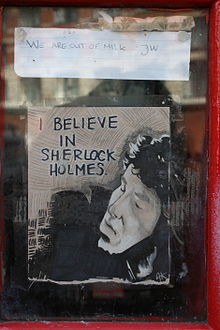

Feminist scholar Adrianne Wadewitz cited Janeites, the devotees of 19th century author Jane Austen, as the earliest example of fandom subculture, beginning around 1870.[2] Another early example was fans of the literary detective Sherlock Holmes,[3] holding public demonstrations of mourning after Holmes was "killed off" in 1893, and creating some of the first fan fiction as early as about 1897 to 1902.[3][4] Outside the scope of media, railway enthusiasts are another early fandom with its roots in the late 19th century that began to gain in popularity and increasingly organize in the first decades of the early 20th century.[5][6]

A wide variety of modern organized Western fan subcultures originated with science fiction fandom, the community of fans of the science fiction and fantasy genres. Science fiction fandom dates back to the 1930s and maintains organized clubs and associations in many cities around the world. Fans have held the annual World Science Fiction Convention since 1939, along with many other events each year, and has created its own jargon, sometimes called "fanspeak".[7] In addition, the Society for Creative Anachronism, a medievalist re-creation group, has its roots in science fiction fandom and was founded by members thereof.[8] Many science fiction and fantasy authors such as Marion Zimmer Bradley,[9] Poul Anderson,[10] Randall Garrett,[10] David D. Friedman,[11] and Robert Asprin[12] have been members of the organization.

Media fandom split from science fiction fandom in the early 1970s with a focus on relationships between characters within TV and movie media franchises, such as Star Trek and The Man from U.N.C.L.E..[13] Fans of these franchises generated creative products like fan art and fan fiction at a time when typical science fiction fandom was focused on critical discussions. The MediaWest convention provided a video room and was instrumental in the emergence of fan vids, or analytic music videos based on a source, in the late 1970s.[14] By the mid-1970s, it was possible to meet fans at science fiction conventions who did not read science fiction, but only viewed it on film or TV.

Anime and manga fandom began in the 1970s in Japan. In America, the fandom also began as an offshoot of science fiction fandom, with fans bringing imported copies of Japanese manga to conventions.[15] Before anime began to be licensed in the U.S., fans who wanted to get a hold of anime would leak copies of anime movies and subtitle them to exchange with friends in the community, thus marking the start of fansubs. While the science fiction and anime fandoms grew in media, the Grateful Dead subculture that emerged in the late 1960s to the early 1970s created a global fandom around hippie culture that would have lasting impacts on society and technology.[16]

Music fandom in the 20th century coincided with the rise of popular music culture, and revolves around the collective enthusiasm and dedication of fans towards specific musical artists, bands, or genres. Common forms of engagement for music fandoms include attending concerts, creating fan art, participating in online communities, and consuming media related to their preferred artist.[17] These communities play an important role in promoting and supporting the careers of artists, as well as shaping cultural trends within the music industry. Some popular examples of music fandom include Beatlemania, Swifties, Deadheads and The Barbz.

The furry fandom refers to the fandom for fictional anthropomorphic animal characters with human personalities and characteristics. The concept of the furry originated at a science fiction convention in 1980,[18] when a drawing of a character from Steve Gallacci's Albedo Anthropomorphics initiated a discussion of anthropomorphic characters in science fiction novels, which in turn initiated a discussion group that met at science fiction and comics conventions.

Additional subjects with significant fandoms include comics, animated cartoons, video games, sports, music, films, television shows, pulp magazines,[19] soap operas,[20] celebrities, and game shows.[21]

Participating in fandom

Members of a fandom associate with one another, often attending fan conventions and publishing and exchanging fanzines and newsletters. Amateur press associations are another form of fan publication and networking. Originally using print-based media, these subcultures have migrated much of their communications and interaction onto the Internet, which is also used for the purpose of archiving detailed information pertinent to their given fanbase. Often, fans congregate on forums and discussion boards to share their love for and criticism of a specific work. This congregation can lead to a high level of organization and community within the fandom, as well as infighting. Although there is some level of hierarchy among most of the discussion boards, and certain contributors may be valued more highly than others, newcomers are most often welcomed into the fold. Most importantly, these sorts of discussion boards can have an effect on the media itself, as was the case in the television show Glee.[22] Trends on discussion boards have been known to influence the writers and producers of shows. The media fandom for the TV series Firefly was able to generate enough corporate interest to create a movie after the series was canceled.[23]

Some fans write fan fiction ("fanfic"), stories based on the universe and characters of their chosen fandom. This fiction can take the form of video-making as well as writing.[24] Fan fiction may or may not tie in with the story's canon; sometimes fans use the story's characters in different situations that do not relate to the plot line at all.

Especially at events, fans may also partake in cosplay, the creation and wearing of costumes designed in the likeness of characters from a source work, which can also be combined with role-playing, reenacting scenes, or inventing likely behavior inspired by their chosen sources.[25]

Others create fan vids, or analytical music videos focusing on the source fandom, and yet others create fan art. Such activities are sometimes known as "fan labor" or "fanac" (an abbreviation for "fan activity"). The advent of the Internet has significantly facilitated fan association and activities. Activities that have been aided by the Internet include the creation of fan "shrines" dedicated to favorite characters, computer screen wallpapers, and avatars. The rise of the Internet has furthermore resulted in the creation of online fan networks who help facilitate the exchange of fanworks.[26]

Some fans create pictures known as edits, which consist of pictures or photos with their chosen fandom characters in different scenarios. These edits are often shared on social media networks such as Instagram, TikTok, Tumblr or Pinterest.[27] In edits, one may see content relating to several different fandoms. Fans in communities online often make gifs or gif sets about their fandoms. Gifs or gif sets can be used to create non-canon scenarios mixing actual content or adding in related content. Gif sets can also capture minute expressions or moments.[28] Fans use gifs to show how they feel about characters or events in their fandom; these are called reaction gifs.[29]

The Temple of the Jedi Order, or Jediism, a self-proclaimed "real living, breathing religion," views itself as separate from the Jedi as portrayed in the Star Wars franchise.[30] Despite this, sociologists view the conflation of religion and fandom in Jediism as legitimate in some sense, classifying both as participatory phenomena.[31]

There are also active fan organizations that participate in philanthropy and create a positive social impact. For example, the Harry Potter Alliance is a civic organization with a strong online component which runs campaigns around human rights issues, often in partnership with other advocacy and nonprofit groups; its membership skews college age and above. Nerdfighters, another fandom formed around Vlogbrothers, a YouTube vlog channel, are mainly high school students united by a common goal of "decreasing world suck".[32] K-pop fans have been involved in various online fan activism campaigns related to Donald Trump's presidential campaign and the Black Lives Matter movement.[33][34]

In film

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2021) |

Notable feature-length documentaries about fandom include Trekkies[35] and A Brony Tale.[36] Slash is a movie released in 2016 about a young boy who writes slash fan fiction.[37] The SiriusXM-produced audio documentary Comic-Con Begins was launched as a six-part series starting June 22, 2021. It presents the history of both the San Diego Comic-Con and the modern fandom scene it helped to spawn, as told by nearly 50 surviving foundational SDCC members, fandom experts, and special guests such as: Kevin Smith, Neil Gaiman, Frank Miller, Felicia Day, Trina Robbins, Maggie Thompson, the Russo brothers, and Bruce Campbell. Cosplay pioneer, scream queen, and foundational SDCC member Brinke Stevens hosts the series.[38] Comic-Con Begins was expanded into the book See You at San Diego: An Oral History of Comic-Con, Fandom, and the Triumph of Geek Culture by creator Mathew Klickstein and published by Fantagraphics on September 6, 2022.[39] The book includes forewords by cartoonists Stan Sakai and Jeff Smith, and an afterword by Wu-Tang Clan's RZA.

In books

Fangirl is a novel written by Rainbow Rowell about a college student who is a fan of a book series called Simon Snow, which is written by a fictional author named Gemma T. Leslie. On October 6, 2015 Rainbow Rowell published a follow-up novel to Fangirl. Carry On is a stand-alone novel set in the fictional world that Cath, the main character of Fangirl writes fan fiction in.[40]

Relationship with the media industry

The film and television entertainment industry refers to the totality of fans devoted to a particular area of interest, organized or not, as the "fanbase".

Media fans, have, on occasion, organized on behalf of canceled television series, with notable success in cases such as Star Trek in 1968, Cagney & Lacey in 1983, Xena: Warrior Princess, in 1995, Roswell in 2000 and 2001 (was canceled with finality at the end of the 2002 season), Farscape in 2002, Firefly in 2002, and Jericho in 2007. (In the case of Firefly the result was the movie Serenity, not another season.) It was likewise the fans who facilitated the push to create a Veronica Mars film through a Kickstarter campaign.[41] Fans of the show Chuck launched a campaign to save the show from being canceled using a Twitter hashtag and buying products from sponsors of the show.[42] Fans of Arrested Development fought for the character Steve Holt to be included in the fourth season. The Save Steve Holt! campaign included a Twitter and Facebook account, a hashtag, and a website.[43]

In the music industry, fandoms have played vital roles in shaping the music of their favorite artists. In 2023, Lana Del Rey was featured in Taylor Swift's song "Snow on the Beach", a track off of her popular album Midnights. Both Swifties, Taylor Swift's loyal fan base, and Lana Del Rey fans were disappointed with the feature, as they felt her contribution was not long enough or sufficiently prominent in the mix. In response, Taylor Swift released an updated version of the track titled "Snow on the Beach (Feat. More Lana Del Rey)", where she sings the entire second verse.[44]

Such outcries, even when unsuccessful, suggest a growing self-awareness on the part of entertainment consumers, who appear increasingly likely to attempt to assert their power as a bloc.[45] Fan activism in support of the 2007 Writers Guild of America strike through Fans4Writers appears to be an extension of this trend.

Science Fiction writers, editors and publishers have participated in science fiction fandom themselves, from Ray Bradbury and Harlan Ellison to Patrick Nielsen Hayden and Toni Weisskopf. Ed Brubaker was a fan of the Captain America comics as a kid and was so upset that Bucky Barnes was killed off that he worked on ways to bring him back. The Winter Soldier arc began in 2004, and in the sixth issue in 2005 it was revealed that the Winter Soldier was Bucky Barnes.[46] Many authors write fan fiction under pseudonyms. Lev Grossman has written stories in the Harry Potter, Adventure Time, and How to Train Your Dragon universes. S.E. Hinton has written about both Supernatural and her own books, The Outsiders.[47] Movie actors often cosplay as other characters to enjoy being a regular fan at cons; for example, Daniel Radcliffe cosplayed as Spider-Man at the 2014 San Diego Comic-Con.[48] Before the release of The Amazing Spider-Man, Andrew Garfield dressed up as Spider-Man and gave an emotional speech about what Spider-Man meant to him and thanking fans for their support.[49]

The relationship between fans and professionals has changed because of access to social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. By giving their follows a glimpse into their everyday life, public figures have a new way of expressing themselves and engaging with their fanbases on a deeper level. Online platforms also give fans more ways to connect and participate in fandoms.[50]

Some fans have made their work in fandom into careers. The book Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James was originally a fan fiction of the Twilight series published on FanFiction.Net. The story was taken down for mature content that violated the site's terms of service. James rewrote the story to take out any references to Twilight and self-published on The Writer's Coffee Shop in May 2011. The book was published by Random House in 2012 and was very popular, selling over 100 million copies.[51] However, many fans were not happy about James using fan fiction to make money and felt it was not in the spirit of the community.[26]

There is contention over fans not being paid for their time or work. Gaming companies use fans to alpha and beta test their games in exchange for early access or promotional merchandise.[26] The TV show Glee used fans to create promotional materials, though they did not compensate them.[52]

The entertainment industry has promoted its work directly to members of the fandom community by sponsoring and presenting at events and conventions dedicated to fandom.[53] Studios frequently create elaborate exhibits,[54] organize panels that feature celebrities and writers of film and television (to promote both existing work and works yet to be released), and engage fans directly with providing Q&A sessions, screening sneak previews, and supplying branded giveaway merchandise. The interest, reception, and reaction of the fandom community to the works being promoted have a marked influence on how film studios and others proceed with the projects and products they exhibit and promote.[55]

Fandoms, for example at Comic Con, can sometimes lead to toxic behavior, including harassing other fans or media creators.[56]

Fandom and technology

The rise of the Internet created new and powerful outlets for fandom. While the principles of fandom largely remain the same, internet users now have the ability to engage in discourse on a global scale, creating an even stronger sense of community among fans. Mark Duffet touches on this point in Popular Music Fandom: Identities, Roles and Practices: "Online social media platforms... have operated as a forthright challenge to the idea that electronic mediation is an alienating and impersonal process".[57]

Fandoms engaging with technology began with early engineers trading Grateful Dead set lists and discussing the setup of the band's concert speaker system, called the "Wall of Sound," on ARPANET, a precursor to the Internet.[58] This led to tape trading over FTP, and the Internet Archive began to add Grateful Dead shows in 1995.[58] Online tape trading communities such as etree evolved into P2P networks trading shows through torrents. After the birth of the World Wide Web, many communities adopted the practices of Deadhead fandom online.

See also

Fandoms by medium

List of notable fandoms

- A Song of Ice and Fire fandom (fans of George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire including A Game of Thrones)

- Beatlemaniacs (fans of the Beatles)

- Bondians (James Bond)

- Bronies (fans of My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic)

- Browncoats (fans of Firefly)

- Deadheads (fans of The Grateful Dead)

- Directioners (fans of One Direction)

- Disney fandom

- Fandom culture in South Korea (fans of Korean pop idols and anime)

- Janeites (fans of Jane Austen)

- Juggalos (fans of Insane Clown Posse)

- Larries (shipping fans of Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson)

- Madonna wannabes (part of Madonna's fandom)

- Marvel fandom

- Moonwalkers (fans of Michael Jackson)

- MSTies (fans of Mystery Science Theater 3000)

- Parrotheads (fans of Jimmy Buffett)

- Potterheads (fans of Harry Potter)

- Railfans

- Science fiction fandom

- Shakira fandom

- Sherlockians (fans of Sherlock Holmes)

- SRKians (fans of Shah Rukh Khan)

- Stargate fandom

- Star Wars fandom

- Swifties (fans of Taylor Swift)

- Tifosi (fans of Italian sports teams or motor vehicles)

- Toonheads

- Tolkien fandom (also known as Tolkienites, or, if only fans of The Lord of the Rings, Ringers)

- Trekkies (fans of Star Trek)

- Ultras, fanatic sports supporters

- Whovians (fans of Doctor Who)

References

- ^ "Fandom - Definition of fandom by Merriam-Webster". merriam-webster.com. 30 March 2024.

- ^ Hefferman, Virginia. "The Pride and Prejudice of Online Fan Culture". Wire. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b Brown, Scott (2009-04-20). "Scott Brown on Sherlock Holmes, Obsessed Nerds, and Fan Fiction". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

Sherlockians called them parodies and pastiches (they still do), and the initial ones appeared within 10 years of the first Holmes 1887 novella, A Study in Scarlet.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes". Fanlore wiki. Fanlore. 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

The earliest recorded examples of this fannish activity are from 1902...

- ^ "About Us | National Railway Historical Society". Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, Inc - History". www.rlhs.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Dr. Gafia's Fan Terms". fanac.org.

- ^ "The History of the Kingdom of The West: Pre-History". 2007-06-09. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "The Priestess of Avalon – Welcome to Avalon!". avalonbooks.net. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ a b Clute, John (1997). "Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997) Society for Creative Anachronism". sf-encyclopedia.uk. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ Friedman, David. "On Restructuring the SCA". www.daviddfriedman.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Home – Great Dark Horde – Horde Space". hordespace.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ Coppa, Francesca (2006). "A Brief History of Media Fandom". In Hellekson, Karen; Busse, Kristina (eds.). Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 41–59. ISBN 978-0-7864-2640-9.

- ^ Walker, Jesse (August–September 2008). "Remixing Television: Francesca Coppa on the vidding underground". Reason Online. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ Bennett, Jason H. "A Preliminary History of American Anime Fandom" (PDF). University of Texas at Arlington. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Ben Grubb (2016-02-14). "The Deadhead Subculture". Grinell College. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ^ Marshall, P. David (2004). New media cultures. Cultural studies in practice. London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-80699-9.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2012-07-15). "Retrospective: An Illustrated Chronology of Furry Fandom, 1966–1996". Flayrah. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ Cook, Michael L. (1983). Mystery fanfare: a composite annotated index to mystery and related fanzines 1963–1981. Popular Press. pp. 24–5. ISBN 0-87972-230-4.

- ^ "Kristian Alfonso, Alison Sweeney and More Shocking Soap Opera Exits|msn.com". MSN.

- ^ ""Gaming's Fringe Cults"|The Escapist". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ Laskari, Isabelle. "Glee Producer and Writer Discuss the Show's Fandom". Hypable. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Miller, Gerri (28 September 2005). "Inside Serenity". How Stuff Works. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry. "Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Digital Cinema, Media Convergence, and Participatory Culture". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ Thorn, Rachel (2004). "Girls And Women Getting Out Of Hand: The Pleasure And Politics Of Japan's Amateur Comics Community". Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan William W. Kelly, ed. State University of New York Press. Archived from the original on 2016-12-14.

- ^ a b c Stanfill, Mel; Condis, Megan (2014-03-15). "Fandom and/as labor". Transformative Works and Cultures. 15. doi:10.3983/twc.2014.0593. ISSN 1941-2258. S2CID 142712852.

- ^ "fandom edits on Tumblr". tumblr.com. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2015-03-09.

- ^ Cain, Bailey Knickerbocker. "The New Curators: Bloggers, Fans And Classic Cinema On Tumblr". M.A. Thesis. University Of Texas, 2014.

- ^ Petersen, Line Nybro (2014). "Sherlock fans talk: Mediatized talk on tumblr". Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook. 12.1: 87–104.

- ^ "Home". www.templeofthejediorder.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ Hanson, Megan (2019-02-20). "Fandom for the Faithless: How Pop Culture Is Replacing Religion". Popdust. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Kilgler-Vilenchik, Neta (2013). "Decreasing World Suck: Fan Communities, Mechanisms of Translation, and Participatory Politics." USC" (PDF).

- ^ Bruner, Raisa (2020-07-25). "How K-Pop Fans Actually Work as a Force for Political Activism in 2020". Time. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (2020-06-05). "How K-pop fans became celebrated online vigilantes". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Trekkies - Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com.

- ^ "A Brony Tale | 2014 Tribeca Festival". Tribeca.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (2016-03-14). "Film Review: 'Slash'". Variety. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ "Column: San Diego Comic-Con gets the superhero treatment in a new SiriusXM podcast". San Diego Union-Tribune. 25 June 2021.

- ^ "See You At San Diego: An Oral History of Comic-Con, Fandom, and the Triumph of Geek Culture". Fantagraphics.

- ^ El-Mohtar, Amal (6 October 2015). "Fan Fiction Comes To Life In 'Carry On'". NPR.org. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ "The Veronica Mars Movie Project". Kickstarter.

- ^ Savage, Christina (2014-03-15). ""Chuck" versus the ratings: Savvy fans and "save our show" campaigns". Transformative Works and Cultures. 15. doi:10.3983/twc.2014.0497. ISSN 1941-2258.

- ^ Locker, Melissa. "Save Steve Holt! Arrested Development Fans Rally for Bit Player". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ Zhan, Jennifer (2023-05-26). "Taylor Swift Turned Up Lana Del Rey's Mic". Vulture. Retrieved 2024-04-20.

- ^ Chin, Bertha; Jones, Bethan; McNutt, Myles; Pebler, Luke (March 15, 2014). "Veronica Mars Kickstarter and crowd funding". Transformative Works and Cultures. 15. doi:10.3983/twc.2014.0519 – via journal.transformativeworks.org.

- ^ "The Story Behind Bucky's Groundbreaking Comic-Book Reinvention As the Winter Soldier". Vulture. 2016-05-06. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ "Lev Grossman, S.E. Hinton, and Other Authors on the Freedom of Writing Fanfiction". Vulture. 2015-03-13. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ Reporter, Tyler McCarthy Trending News (2014-07-28). "Daniel Radcliffe Disguised Himself As Spider-Man During Comic-Con". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ "Watch Andrew Garfield's Earnest Spider-Man Speech at Comic-Con". Vulture. 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ Bennett, Lucy (2014). "Tracing Textual Poachers: Reflections on the development of fan studies and digital fandom". The Journal of Fandom Studies. 2.1: 5–20.

- ^ "'Fifty Shades of Grey' started out as 'Twilight' fan fiction before becoming an international phenomenon". Business Insider. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ Stork, Matthias (2014-03-15). "The cultural economics of performance space: Negotiating fan, labor, and marketing practice in "Glee"'s transmedia geography". Transformative Works and Cultures. 15. doi:10.3983/twc.2014.0490. ISSN 1941-2258.

- ^ Graser, Marc (2013-07-15). "Comic-Con: Universal Destroys San Diego Convention Center for 'Oblivion'". Variety. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ Maass, Arturo Garcia, Dave (2018-07-23). "25 Best Things We Saw at San Diego Comic Con 2018". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamato, Jen (19 July 2017). "Inside Comic-Con's Hall H, the most important room in Hollywood". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ Carson, Erin. "Comic-Con 2018 is all about the fans. So why are so many of them mad?". CNET.

- ^ Duffett, Mark, ed. (2014). Popular music fandom: identities, roles and practices. Routledge studies in popular music. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-50639-7.

- ^ a b Scott Beauchamp (2017-06-14). "The Internet Is the Grateful Dead". Pacific Standard. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

External links

- "Who owns fandom?" – Salon.com December 13, 2000

- "Rank and Phile" Archived 2008-05-12 at the Wayback Machine – Arts Hub feature, August 12, 2005

- ELIZABETH MINKEL (February 28, 2024). "Lots of People Make Money on Fanfic. Just Not the Authors". Wired.

- Organization for Transformative Works – Non-profit organization promoting fandom and archiving fanworks.

- "Surviving Fandom" – Mookychick June 24, 2013

- Harry Potter Alliance - official website