Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire | |

|---|---|

| 330–1453 | |

The empire in 555 under Justinian the Great, at its greatest extent since the fall of the Western Roman Empire (its vassals in pink) | |

The change of territory of the Byzantine Empire (476–1400) | |

| Capital | Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) |

| Common languages | |

| Religion | Christianity (state) |

| Demonym(s) | Byzantine Roman |

| Government | Autocracy |

| Notable emperors | |

• 306–337 | Constantine I |

• 379–395 | Theodosius I |

• 408–450 | Theodosius II |

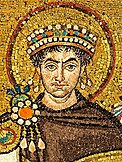

• 527–565 | Justinian I |

• 610–641 | Heraclius |

• 717–741 | Leo III |

• 976–1025 | Basil II |

• 1081–1118 | Alexios I |

• 1143–1180 | Manuel I |

• 1261–1282 | Michael VIII |

• 1449–1453 | Constantine XI |

| Historical era | Late Antiquity to Late Middle Ages |

| Population | |

• 457 | 16,000,000 |

• 565 | 26,000,000 |

• 775 | 7,000,000 |

• 1025 | 12,000,000 |

• 1320 | 2,000,000 |

| Currency | Solidus, denarius, and hyperpyron |

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centered in Constantinople during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world. The term "Byzantine Empire" was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as "Romans".[a] Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to Byzantium, the adoption of state Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin, modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier Roman Empire and the later Byzantine Empire.

During the earlier Pax Romana period, the western parts of the empire became increasingly Latinised, while the eastern parts largely retained their preexisting Hellenistic culture. This created a dichotomy between the Greek East and Latin West. These cultural spheres continued to diverge after Constantine I (r. 324–337) moved the capital to Constantinople and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the state religion, and other religious practices were proscribed. Greek gradually replaced Latin for official use as Latin fell into disuse.

The empire experienced several cycles of decline and recovery throughout its history, reaching its greatest extent after the fall of the west during the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), who briefly reconquered much of Italy and the western Mediterranean coast. The appearance of plague and a devastating war with Persia exhausted the empire's resources; the early Muslim conquests that followed saw the loss of the empire's richest provinces—Egypt and Syria—to the Rashidun Caliphate. In 698, Africa was lost to the Umayyad Caliphate, but the empire subsequently stabilised under the Isaurian dynasty. The empire was able to expand once more under the Macedonian dynasty, experiencing a two-century-long renaissance. This came to an end in 1071, with the defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. Thereafter, periods of civil war and Seljuk incursion resulted in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The empire recovered during the Komnenian restoration, and Constantinople would remain the largest and wealthiest city in Europe until the 13th century.

The empire was largely dismantled in 1204, following the Sack of Constantinople by Latin armies at the end of the Fourth Crusade; its former territories were then divided into competing Greek rump states and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the reconstituted empire would wield only regional power during its final two centuries of existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans in perennial wars fought throughout the 14th and 15th centuries. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 ultimately brought the empire to an end. Many refugees who had fled the city after its capture settled in Italy and throughout Europe, helping to ignite the Renaissance. The fall of Constantinople is sometimes used to mark the dividing line between the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

Nomenclature

The inhabitants of the empire, now generally termed Byzantines, thought of themselves as Romans (Romaioi). Their Islamic neighbours similarly called their empire the "land of the Romans" (Bilād al-Rūm), but the people of medieval Western Europe preferred to call them "Greeks" (Graeci), due to having a contested legacy to Roman identity and to associate negative connotations from ancient Latin literature.[1] The adjective "Byzantine", which derived from Byzantion (Latinised as Byzantium), the name of the Greek settlement Constantinople was established on, was only used to describe the inhabitants of that city; it did not refer to the empire, which they called Romanía—"Romanland".[2]

After the empire's fall, early modern scholars referred to the empire by many names, including the "Empire of Constantinople", the "Empire of the Greeks", the "Eastern Empire", the "Late Empire", the "Low Empire", and the "Roman Empire".[3] The increasing use of "Byzantine" and "Byzantine Empire" likely started with the 15th-century historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles, whose works were widely propagated, including by Hieronymus Wolf. "Byzantine" was used adjectivally alongside terms such as "Empire of the Greeks" until the 19th century.[4] It is now the primary term, used to refer to all aspects of the empire; some modern historians believe that, as an originally prejudicial and inaccurate term, its use should be halted.[5]

History

As the historiographical periodizations of "Roman history", "late antiquity", and "Byzantine history" significantly overlap, there is no consensus on a "foundation date" for the Byzantine Empire, if there was one at all. The growth of the study of "late antiquity" has led to some historians setting a start date in the seventh or eighth centuries.[6] Others believe a "new empire" began during changes in c. 300 AD.[7] Still others hold that these starting points are too early or too late, and instead begin c. 500.[8] Geoffrey Greatrex believes that it is impossible to precisely date the foundation of the Byzantine Empire.[9]

Early history (pre-518)

In a series of conflicts between the third and first centuries BC, the Roman Republic gradually established hegemony over the eastern Mediterranean, while its government ultimately transformed into the one-person rule of an emperor. The Roman Empire enjoyed a period of relative stability until the third century AD, when a combination of external threats and internal instabilities caused the Roman state to splinter as regional armies acclaimed their generals as "soldier-emperors".[10] One of these, Diocletian (r. 284–305), seeing that the state was too big to be ruled by one man, attempted to fix the problem by instituting a Tetrarchy, or rule of four, and dividing the empire into eastern and western halves. Although the Tetrarchy system quickly failed, the division of the empire proved an enduring concept.[11]

Constantine I (r. 306–337) secured sole power in 324. Over the following six years, he rebuilt the city of Byzantium as a capital city, which was renamed Constantinople. Rome, the previous capital, was further from the important eastern provinces and in a less strategically important location; it was not esteemed by the "soldier-emperors" who ruled from the frontiers or by the empire's population who, having been granted citizenship, considered themselves "Roman".[12] Constantine extensively reformed the empire's military and civil administration and instituted the gold solidus as a stable currency.[13] He favoured Christianity, which he had converted to in 312.[14] Constantine's dynasty fought a lengthy conflict against Sasanid Persia and ended in 363 with the death of his son-in-law Julian.[15] The short Valentinianic dynasty, occupied with wars against barbarians, religious debates, and anti-corruption campaigns, ended in the East with the death of Valens at the Battle of Adrianople in 378.[16]

Valens's successor, Theodosius I (r. 379–395), restored political stability in the east by allowing the Goths to settle in Roman territory;[17] he also twice intervened in the western half, defeating the usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius in 388 and 394 respectively.[18] He actively condemned paganism, confirmed the primacy of Nicene Christianity over Arianism, and established Christianity as the Roman state religion.[19] He was the last emperor to rule both the western and eastern halves of the empire;[20] after his death, the West would be destabilised by a succession of "soldier-emperors", unlike the East, where administrators would continue to hold power. Theodosius II (r. 408–450) largely left the rule of the east to officials such as Anthemius, who constructed the Theodosian Walls to defend Constantinople, now firmly entrenched as Rome's capital.[21]

Theodosius' reign was marked by the theological dispute over Nestorianism, which was eventually deemed heretical, and by the formulation of the Codex Theodosianus law code.[22] It also saw the arrival of Attila's Huns, who ravaged the Balkans and exacted a massive tribute from the empire; Attilla however switched his attention to the rapidly-deteriorating western empire, and his people fractured after his death in 453.[23] After Leo I (r. 457–474) failed in his 468 attempt to reconquer the west, the warlord Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus in 476, killed his titular successor Julius Nepos in 480, and the office of western emperor was formally abolished.[24]

Through a combination of luck, cultural factors, and political decisions, the Eastern empire never suffered from rebellious barbarian vassals and was never ruled by barbarian warlords—the problems which ensured the downfall of the West.[25] Zeno (r. 474–491) convinced the problematic Ostrogoth king Theodoric to take control of Italy from Odoacer, which he did; dying with the empire at peace, Zeno was succeeded by Anastasius I (r. 491–518).[26] Although his Monophysitism brought occasional issues, Anastasius was a capable administrator and instituted several successful financial reforms including the abolition of the chrysargyron tax. He was the first emperor to die with no serious problems affecting his empire since Diocletian.[27]

518–717

The reign of Justinian I was a watershed in Byzantine history.[28] Following his accession in 527, the law-code was rewritten as the influential Corpus Juris Civilis and Justinian produced extensive legislation on provincial administration;[29] he reasserted imperial control over religion and morality through purges of non-Christians and "deviants";[30] and having ruthlessly subdued the 532 Nika revolt he rebuilt much of Constantinople, including the original Hagia Sophia.[31] Justinian took advantage of political instability in Italy to attempt the reconquest of lost western territories. The Vandal Kingdom in North Africa was subjugated in 534 by the general Belisarius, who then invaded Italy; the Ostrogothic Kingdom was destroyed in 554.[32]

In the 540s, however, Justinian began to suffer reversals on multiple fronts. Taking advantage of Constantinople's preoccupation with the West, Khosrow I of the Sasanian Empire invaded Byzantine territory and sacked Antioch in 540.[33] Meanwhile, the emperor's internal reforms and policies began to falter, not helped by a devastating plague that killed a large proportion of the population and severely weakened the empire's social and financial stability.[34] The most difficult period of the Ostrogothic war, against their king Totila, came during this decade, while divisions among Justinian's advisors undercut the administration's response.[35] He also did not fully heal the divisions in Chalcedonian Christianity, as the Second Council of Constantinople failed to make a real difference.[36] Justinian died in 565; his reign saw more success than that of any other Byzantine emperor, yet he left his empire under massive strain.[37]

Financially and territorially overextended, Justin II (r. 565–578) was soon at war on many fronts. The Lombards, fearing the aggressive Avars, conquered much of northern Italy by 572.[38] The Sasanian wars restarted that year, and continued until the emperor Maurice finally emerged victorious in 591; by that time, the Avars and Slavs had repeatedly invaded the Balkans, causing great instability.[39] Maurice campaigned extensively in the region during the 590s, but although he managed to re-establish Byzantine control up to the Danube, he pushed his troops too far in 602—they mutinied, proclaimed an officer named Phocas as emperor, and executed Maurice.[40] The Sasanians seized their moment and reopened hostilities; Phocas was unable to cope and soon faced a major rebellion led by Heraclius. Phocas lost Constantinople in 610 and was soon executed, but the destructive civil war accelerated the empire's decline.[41]

Bottom: the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, critically important during the 717–718 siege.

Under Khosrow II, the Sassanids occupied the Levant and Egypt and pushed into Asia Minor, while Byzantine control of Italy slipped and the Avars and Slavs ran riot in the Balkans.[42] Although Heraclius repelled a siege of Constantinople in 626 and then, brilliantly, invaded and defeated the Sassanids in 627, this was a pyrrhic victory.[43] The early Muslim conquests soon saw the conquest of the Levant, of Egypt, and of the Sassanid Empire by the newly-formed Arabic Rashidun Caliphate.[44] By Heraclius' death in 641, the empire had been severely reduced economically as well as territorially—the loss of the wealthy eastern provinces had deprived Constantinople of three-quarters of its revenue.[45]

The next seventy-five years are poorly documented.[46] Arab raids into Asia Minor began almost immediately, and the Byzantines resorted to holding fortified centres and avoiding battle at all costs; although it was invaded annually, Anatolia avoided permanent Arab occupation.[47] The outbreak of the First Fitna in 656 gave Byzantium breathing space, which it used wisely: some order was restored in the Balkans by Constans II (r. 641–668),[48] who began the administrative reorganisation known as the "theme system", in which troops were allocated to defend specific provinces.[49] With the help of the recently rediscovered Greek fire, Constantine IV (r. 668–685) repelled the Arab efforts to capture Constantinople in the 670s,[50] but suffered a reversal against the Bulgars, who soon established an empire in the northern Balkans.[51] Nevertheless, he and Constans had done enough to secure the empire's position, especially as the Umayyad Caliphate was undergoing another civil war.[52]

Justinian II sought to build on the stability secured by his father Constantine but was overthrown in 695 after attempting to exact too much from his subjects; over the next twenty-two years, six more rebellions followed in an era of political instability.[53] The reconstituted caliphate sought to break Byzantium by taking Constantinople, but the newly crowned Leo III managed to repel the 717–718 siege, the first major setback of the Muslim conquests.[54]

718–867

Leo and his son Constantine V (r. 741–775), two of the most capable Byzantine emperors, withstood continued Arab attacks, civil unrest, and natural disasters, and reestablished the state as a major regional power.[55] Leo's reign produced the Ecloga, a new code of law to succeed that of Justinian II,[56] and continued to reform the "theme system" in order to lead offensive campaigns against the Muslims, culminating in a decisive victory in 740.[57] Constantine overcame an early civil war against his brother-in-law Artabasdos, made peace with the new Abbasid Caliphate, campaigned successfully against the Bulgars, and continued to make administrative and military reforms.[58] However, due to both emperors' support for the Byzantine Iconoclasm, which opposed the use of religious icons, they were later vilified by Byzantine historians;[59] Constantine's reign also saw the loss of Ravenna to the Lombards, and the beginning of a split with the Roman papacy.[60]

In 780, Empress Irene assumed power on behalf of her son Constantine VI.[61] Although she was a capable administrator who temporarily resolved the iconoclasm controversy,[62] the empire was destabilized by her feud with her son. The Bulgars and Abbasids meanwhile inflicted numerous defeats on the Byzantine armies, and the papacy crowned Charlemagne as Roman emperor in 800.[63] In 802, the unpopular Irene was overthrown by Nikephoros I; he reformed the empire's administration but died in battle against the Bulgars in 811.[64] Military defeats and societal disorder, especially the resurgence of iconoclasm, characterised the next eighteen years.[65]

Stability was somewhat restored during the reign of Theophilos (r. 829–842), who exploited economic growth to complete construction programs, including rebuilding the sea walls of Constantinople, overhaul provincial governance, and wage inconclusive campaigns against the Abbasids.[66] After his death, his empress Theodora, ruling on behalf of her son Michael III, permanently extinguished the iconoclastic movement;[67] the empire prospered under their sometimes-fraught rule. However, Michael was posthumously vilified by historians loyal to the dynasty of his successor Basil I, who assassinated him in 867 and who was given credit for his predecessor's achievements.[68]

867–1081

The accession of Basil I to the throne in 867 marks the beginning of the Macedonian dynasty, which ruled for 150 years. This dynasty included some of the ablest emperors in Byzantium's history, and the period is one of revival. The empire moved from defending against external enemies to reconquest of territories.[69] The Macedonian dynasty was characterised by a cultural revival in spheres such as philosophy and the arts. There was a conscious effort to restore the brilliance of the period before the Slavic and subsequent Arab invasions, and the Macedonian era has been dubbed the "Golden Age" of Byzantium.[69] Although the empire was significantly smaller than during the reign of Justinian I, it had regained much strength, as the remaining territories were less geographically dispersed and more politically, economically, and culturally integrated.

Between 1021 and 1022, following years of tensions, Basil II led a series of victorious campaigns against the Kingdom of Georgia, resulting in the annexation of several Georgian provinces to the empire. Basil's successors also annexed Bagratid Armenia in 1045. Importantly, both Georgia and Armenia were significantly weakened by the Byzantine administration's policy of heavy taxation and abolishing of the levy. The weakening of Georgia and Armenia played a significant role in the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071.[70]

Basil II is considered among the most capable Byzantine emperors and his reign as the apex of the empire in the Middle Ages. By 1025, the date of Basil II's death, the Byzantine Empire stretched from Armenia in the east to Calabria in southern Italy in the west.[71] Many successes had been achieved, ranging from the conquest of Bulgaria to the annexation of parts of Georgia and Armenia, and the reconquests of Crete, Cyprus, and the important city of Antioch. These were not temporary tactical gains but long-term reconquests.[72]

The Byzantine Empire fell into a period of difficulties, caused to a large extent by the undermining of the theme system and the neglect of the military. Nikephoros II, John Tzimiskes, and Basil II shifted the emphasis of the military divisions (τάγματα, tagmata) from a reactive, defence-oriented citizen army into an army of professional career soldiers, increasingly dependent on foreign mercenaries. Mercenaries were expensive, however, and as the threat of invasion receded in the 10th century, so did the need for maintaining large garrisons and expensive fortifications.[73] Basil II left a burgeoning treasury upon his death, but he neglected to plan for his succession. None of his immediate successors had any particular military or political talent, and the imperial administration increasingly fell into the hands of the civil service. Incompetent efforts to revive the Byzantine economy resulted in severe inflation and a debased gold currency. The army was seen as both an unnecessary expense and a political threat. Several standing local units were demobilised, further augmenting the army's dependence on mercenaries, which could be retained and dismissed on an as-needed basis.[74]

At the same time, Byzantium was faced with new enemies. Its provinces in southern Italy were threatened by the Normans who arrived in Italy at the beginning of the 11th century. During a period of strife between Constantinople and Rome culminating in the East-West Schism of 1054, the Normans advanced slowly but steadily into Byzantine Italy.[75] Reggio, the capital of the tagma of Calabria, was captured in 1060 by Robert Guiscard, followed by Otranto in 1068. Bari, the main Byzantine stronghold in Apulia, was besieged in August 1068 and fell in April 1071.[76]

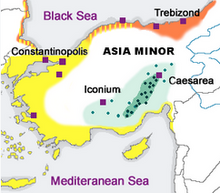

About 1053, Constantine IX disbanded what the historian John Skylitzes calls the "Iberian Army", which consisted of 50,000 men, and it was turned into a contemporary Drungary of the Watch. Two other knowledgeable contemporaries, the former officials Michael Attaleiates and Kekaumenos, agree with Skylitzes that by demobilising these soldiers, Constantine did catastrophic harm to the empire's eastern defences. The emergency lent weight to the military aristocracy in Anatolia, who in 1068 secured the election of one of their own, Romanos Diogenes, as emperor. In the summer of 1071, Romanos undertook a massive eastern campaign to draw the Seljuks into a general engagement with the Byzantine army. At the Battle of Manzikert, Romanos suffered a surprise defeat by Sultan Alp Arslan and was captured. Alp Arslan treated him with respect and imposed no harsh terms on the Byzantines.[74] In Constantinople a coup put in power Michael Doukas, who soon faced the opposition of Nikephoros Bryennios and Nikephoros III Botaneiates. By 1081, the Seljuks had expanded their rule over virtually the entire Anatolian plateau from Armenia in the east to Bithynia in the west, and they had founded their capital at Nicaea, just 90 kilometres (56 miles) from Constantinople.[77]

Komnenian dynasty and the Crusades

Alexios I and the First Crusade

The Komnenian dynasty attained full power under Alexios I in 1081. From the outset of his reign, Alexios faced a formidable attack by the Normans under Guiscard and his son Bohemund of Taranto, who captured Dyrrhachium and Corfu and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly. Guiscard's death in 1085 temporarily eased the Norman problem. The following year, the Seljuq sultan died, and the sultanate was split by internal rivalries. By his own efforts, Alexios defeated the Pechenegs, who were caught by surprise and annihilated at the Battle of Levounion on 28 April 1091.[78]

Having achieved stability in the West, Alexios could turn his attention to the severe economic difficulties and the disintegration of the empire's traditional defences.[79] However, he still did not have enough manpower to recover the lost territories in Asia Minor and to advance against the Seljuks. At the Council of Piacenza in 1095, envoys from Alexios spoke to Pope Urban II about the suffering of the Christians of the East and underscored that without help from the West, they would continue to suffer under Muslim rule.[80] Urban saw Alexios request as a dual opportunity to cement Western Europe and reunite the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church under his rule.[80] On 27 November 1095, Urban called the Council of Clermont and urged all those present to take up arms under the sign of the Cross and launch an armed pilgrimage to recover Jerusalem and the East from the Muslims. The response in Western Europe was overwhelming.[78] Alexios was able to recover a number of important cities, islands and much of western Asia Minor. The Crusaders agreed to become Alexios' vassals under the Treaty of Devol in 1108, which marked the end of the Norman threat during Alexios' reign.[81]

John II, Manuel I, and the Second Crusade

Alexios's son John II Komnenos succeeded him in 1118 and ruled until 1143. John was a pious and dedicated emperor who was determined to undo the damage to the empire suffered at the Battle of Manzikert half a century earlier.[82] Famed for his piety and his remarkably mild and just reign, John was an exceptional example of a moral ruler at a time when cruelty was the norm.[83] For this reason, he has been called the Byzantine Marcus Aurelius. During his twenty-five-year reign, John made alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the West and decisively defeated the Pechenegs at the Battle of Beroia.[84] He thwarted Hungarian and Serbian threats during the 1120s, and in 1130 he allied himself with German Emperor Lothair III against Norman King Roger II of Sicily.[85]

In the later part of his reign, John focused his activities on the East, personally leading numerous campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor. His campaigns fundamentally altered the balance of power in the East, forcing the Turks onto the defensive, while restoring many towns, fortresses, and cities across the peninsula to the Byzantines. He defeated the Danishmend Emirate of Melitene and reconquered all of Cilicia, while forcing Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch, to recognise Byzantine suzerainty. In an effort to demonstrate the emperor's role as the leader of the Christian world, John marched into the Holy Land at the head of the combined forces of the empire and the Crusader states; yet despite his great vigour pressing the campaign, his hopes were disappointed by the treachery of his Crusader allies.[86] In 1142, John returned to press his claims to Antioch, but he died in the spring of 1143 following a hunting accident.

John's chosen heir was his fourth son, Manuel I Komnenos, who campaigned aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and in the east. In Palestine, Manuel allied with the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and sent a large fleet to participate in a combined invasion of Fatimid Egypt. Manuel reinforced his position as overlord of the Crusader states, with his hegemony over Antioch and Jerusalem secured by agreement with Raynald, Prince of Antioch, and Amalric of Jerusalem.[87] In an effort to restore Byzantine control over the ports of southern Italy, he sent an expedition to Italy in 1155, but disputes within the coalition led to the eventual failure of the campaign. Despite this military setback, Manuel's armies successfully invaded the southern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1167, defeating the Hungarians at the Battle of Sirmium. By 1168, nearly the whole of the eastern Adriatic coast lay in Manuel's hands.[88] Manuel made several alliances with the pope and Western Christian kingdoms, and he successfully handled the passage of the crusaders through his empire.[89]

In the East, Manuel suffered a major defeat in 1176 at the Battle of Myriokephalon against the Turks. Yet the losses were quickly recovered, and in the following year Manuel's forces inflicted a defeat upon a force of "picked Turks".[90] The Byzantine commander John Vatatzes, who destroyed the Turkish invaders at the Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir, brought troops from the capital and was able to gather an army along the way, a sign that the Byzantine army remained strong and that the defensive programme of western Asia Minor was still successful.[91] John and Manuel pursued active military policies, and both deployed considerable resources on sieges and city defences; aggressive fortification policies were at the heart of their imperial military policies.[92] Despite the defeat at Myriokephalon, the policies of Alexios, John and Manuel resulted in vast territorial gains, increased frontier stability in Asia Minor, and secured the stabilisation of the empire's European frontiers. From c. 1081 to c. 1180, the Komnenian army assured the empire's security, enabling Byzantine civilisation to flourish.[93]

This allowed the Western provinces to achieve an economic revival that continued until the close of the century. It has been argued that Byzantium under the Komnenian rule was more prosperous than at any time since the Persian invasions of the 7th century. During the 12th century, population levels rose and extensive tracts of new agricultural land were brought into production. Archaeological evidence from both Europe and Asia Minor shows a considerable increase in the size of urban settlements, together with a notable upsurge in new towns. Trade was also flourishing; the Venetians, the Genoese and others opened up the ports of the Aegean to commerce, shipping goods from the Crusader states and Fatimid Egypt to the west and trading with the empire via Constantinople.[94]

Decline and disintegration

Angelid dynasty

Manuel's death on 24 September 1180 left his 11-year-old son Alexios II Komnenos on the throne. Alexios was highly incompetent in the office, and with his mother Maria of Antioch's Frankish background, his regency was unpopular.[95] Eventually, Andronikos I Komnenos, a grandson of Alexios I, overthrew Alexios II in a violent coup d'état.[96] After eliminating his potential rivals, he had himself crowned as co-emperor in September 1183. He eliminated Alexios II and took his 12-year-old wife Agnes of France for himself.[96]

Andronikos began his reign well; in particular, the measures he took to reform the government of the empire have been praised by historians. According to George Ostrogorsky, Andronikos was determined to root out corruption: under his rule, the sale of offices ceased; selection was based on merit, rather than favouritism; officials were paid an adequate salary to reduce the temptation of bribery. In the provinces, Andronikos's reforms produced a speedy and marked improvement.[97] Gradually, however, Andronikos's reign deteriorated. The aristocrats were infuriated against him, and to make matters worse, Andronikos seemed to have become increasingly unbalanced; executions and violence became increasingly common, and his reign turned into a reign of terror.[98] Andronikos seemed almost to seek the extermination of the aristocracy as a whole. The struggle against the aristocracy turned into wholesale slaughter, while the emperor resorted to ever more ruthless measures to shore up his regime.[97]

Despite his military background, Andronikos failed to deal with Isaac Komnenos, Béla III of Hungary who reincorporated Croatian territories into Hungary, and Stephen Nemanja of Serbia who declared his independence from the Byzantine Empire. Yet, none of these troubles compared to William II of Sicily's invasion force of 300 ships and 80,000 men, arriving in 1185 and sacking Thessalonica.[99] Andronikos mobilised a small fleet of 100 ships to defend the capital, but other than that he was indifferent to the populace. He was finally overthrown when Isaac II Angelos, surviving an imperial assassination attempt, seized power with the aid of the people and had Andronikos killed.[100]

The reign of Isaac II, and more so that of his brother Alexios III, saw the collapse of what remained of the centralised machinery of Byzantine government and defence. Although the Normans were driven out of Greece, in 1186 the Vlachs and Bulgars began a rebellion that led to the formation of the Second Bulgarian Empire. The internal policy of the Angeloi was characterised by the squandering of the public treasure and fiscal maladministration. Imperial authority was severely weakened, and the growing power vacuum at the centre of the empire encouraged fragmentation. There is evidence that some Komnenian heirs had set up a semi-independent state in Trebizond before 1204.[101] According to Alexander Vasiliev, "the dynasty of the Angeloi, Greek in its origin, ... accelerated the ruin of the Empire, already weakened without and disunited within."[102]

Fourth Crusade and aftermath

In 1198, Pope Innocent III broached the subject of a new crusade through legates and encyclical letters.[103] The stated intent of the crusade was to conquer Egypt, the centre of Muslim power in the Levant. The Crusader army arrived at Venice in the summer of 1202 and hired the Venetian fleet to transport them to Egypt. As a payment to the Venetians, they captured the (Christian) port of Zara in Dalmatia (the vassal city of Venice, which had rebelled and placed itself under Hungary's protection in 1186).[104] Shortly afterward, Alexios IV Angelos, son of the deposed and blinded Emperor Isaac II, made contact with the Crusaders. Alexios offered to reunite the Byzantine church with Rome, pay the Crusaders 200,000 silver marks, join the crusade, and provide all the supplies they needed to reach Egypt.[105]

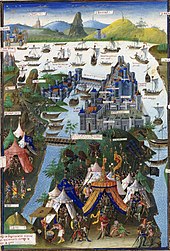

The crusaders arrived at Constantinople in the summer of 1203 and quickly attacked, starting a major fire that damaged large parts of the city, and briefly seized control. Alexios III fled from the capital, and Alexios Angelos was elevated to the throne as Alexios IV along with his blind father Isaac. Alexios IV and Isaac II were unable to keep their promises and were deposed by Alexios V. The crusaders again took the city on 13 April 1204, and Constantinople was subjected to pillage and massacre by the rank and file for three days. Many priceless icons, relics and other objects later turned up in Western Europe, a large number in Venice. According to chronicler Niketas Choniates, a prostitute was even set up on the patriarchal throne.[106] When order had been restored, the crusaders and the Venetians proceeded to implement their agreement; Baldwin of Flanders was elected emperor of a new Latin Empire, and the Venetian Thomas Morosini was chosen as patriarch. The lands divided up among the leaders included most of the former Byzantine possessions.[107] Although Venice was more interested in commerce than conquering territory, it took key areas of Constantinople, and the Doge took the title of "Lord of a Quarter and Half a Quarter of the Roman Empire".[108]

After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin crusaders, two Byzantine successor states were established: the Empire of Nicaea and the Despotate of Epirus. A third, the Empire of Trebizond, was created after Alexios Komnenos, commanding the Georgian expedition in Chaldia[109] a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople, found himself de facto emperor and established himself in Trebizond. Of the three successor states, Epirus and Nicaea stood the best chance of reclaiming Constantinople. The Nicaean Empire struggled to survive the next few decades, however, and by the mid-13th century it had lost much of southern Anatolia.[110] The weakening of the Sultanate of Rûm following the Mongol invasion in 1242–1243 allowed many beyliks and ghazis to set up their own principalities in Anatolia, weakening the Byzantine hold on Asia Minor.[111] In time, one of the Beys, Osman I, created the Ottoman Empire that would eventually conquer Constantinople. However, the Mongol invasion also gave Nicaea a temporary respite from Seljuk attacks, allowing it to concentrate on the Latin Empire to its north.

The Empire of Nicaea, founded by the Laskarid dynasty, managed to recapture Constantinople in 1261 and defeat Epirus. This led to a short-lived revival of Byzantine fortunes under Michael VIII Palaiologos, but the war-ravaged empire was ill-equipped to deal with the enemies that surrounded it. To maintain his campaigns against the Latins, Michael pulled troops from Asia Minor and levied crippling taxes on the peasantry, causing much resentment.[112] Massive construction projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damage of the Fourth Crusade, but none of these initiatives were of any comfort to the farmers in Asia Minor suffering raids from Muslim ghazis.[113]

Rather than holding on to his possessions in Asia Minor, Michael chose to expand the empire, gaining only short-term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Church to submit to Rome, again a temporary solution for which the peasantry hated Michael and Constantinople.[113] The efforts of Andronikos II and later his grandson Andronikos III marked Byzantium's last genuine attempts to restoring the glory of the empire. However, the use of mercenaries by Andronikos II often backfired, with the Catalan Company ravaging the countryside and increasing resentment towards Constantinople.[114]

Fall

The situation became worse for Byzantium during the civil wars after Andronikos III died. A six-year-long civil war devastated the empire, allowing the Serbian ruler Stefan Dušan to overrun most of the empire's remaining territory and establish a Serbian Empire. In 1354, an earthquake at Gallipoli devastated the fort, allowing the Ottomans (who were hired as mercenaries during the civil war by John VI Kantakouzenos) to establish themselves in Europe.[115][116] By the time the Byzantine civil wars had ended, the Ottomans had defeated the Serbians and subjugated them as vassals. Following the Battle of Kosovo, much of the Balkans became dominated by the Ottomans.[117]

Constantinople by this stage was underpopulated and dilapidated. The population of the city had collapsed so severely that it was now little more than a cluster of villages separated by fields. On 2 April 1453, Sultan Mehmed's army of 80,000 men and large numbers of irregulars laid siege to the city.[118] Despite a desperate last-ditch defence of the city by the massively outnumbered Christian forces (c. 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreign),[119] Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after a two-month siege on 29 May 1453. The final Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.[120]

Geography

The Empire was centered in what is now Greece and Turkey with its metropolis Constantinople.[121] In the 5th century, it controlled the eastern basis of the Mediterranean running east from Singidunum (modern Belgrade) in a line through the Adriatic Sea and south to Cyrene, Libya.[122] This encompassed most of the Balkans, all of modern Greece, Turkey, Syria, Palestine; North Africa, primarily with modern Egypt and Libya; the Aegean islands along with Crete, Cyprus and Sicily, and a small settlement in Crimea.[121]

The landscape of the Empire was defined by the fertile fields of Anatolia, long mountain ranges and rivers such as the Danube.[123] In the north and west are the Balkans, the corridors between the mountain ranges of Pindos, the Dinaric Alps, the Rhodopes and the Balkans, and in south and east is Anatolia, the Pontic Mountains and Taurus-Anti-Taurus range, served as passages for armies, while the Caucasus mountains lay between the Empire and its eastern neighbours.[124]

Roman roads connected the Empire by land, with the Via Egnatia running from Constantinople to the Albanian coast through Macedonia and the Via Traiana to Adrianople (modern Edirne), Serdica (modern Sofia) and Singidunum.[125] By water, Crete, Cyprus and Sicily were key naval points and the main ports connecting Constantinople were Alexandria, Gaza, Caesarea and Antioch.[126] The Aegean sea was considered an internal lake to the Empire.[124]

Society

Transition into an Eastern Christian empire

In 212 citizenship was granted across the entire Empire. Roman citizenship was an innovation of the Roman state, where people with no direct territorial claim to the city of Rome could have it.[127] The decision in 212 would affect two-thirds of the Empire's population, fundamentally changing its nature.[128] In 249, Decius required all subjects to make a public sacrifice to the gods for the Empire, which following 212 was unprecedented in scale and marked the progression towards uniform religious practice.[129]

Diocletian's constitutional reforms from 284 ended the facade of dyarchy created by the reforms by Augustus that created the principate.[130] The state would begin to intervene more in the private matters of families.[131] Constantine's support for Christianity and moving the imperial seat east, changed the power structure permanently: the formation of the Constantinople Senate provided the East political independence.[130] Theodosius issued a series of edicts essentially banning pagan religion: pagan sacrifices, ceremonies, and access to pagan places of worship were restricted.[132] The last recorded Olympic Games had been held in 393.[133]

By the fifth century CE, Hellenic culture had heavily impacted Roman identity.[134] The theological debates in the Christian Church increased the importance of the Greek language, in turn making it highly dependent on Hellenic thought.[135] It enabled philosophy like Neoplatonism to loom large on Christian theology.[136] Anthony Kaldellis views Christianity as "bringing no economic, social, or political changes to the state other than being more deeply integrated into it".[137]

Slavery

There were 3 million enslaved people (or 15% of the population) around the time of the Diocletian reforms.[138] Youval Rotman calls the changes to slavery during this period, as "different degrees of unfreedom".[139] Previous slave roles became high-demand free market professions (like tutors), and the state encouraged the coloni, tenants bound to the land, as a new legal category between free and slave.[140] In 294, the enslavement of children was forbidden; Honorius (r. 393–423) would begin to free enslaved people that were battle captives, and later emperors would free the slaves of conquered people.[141][142] Christianity as an institution had no direct impact, but state policies prohibited enslaved Christians, had limits on trading them, and made it a bishop's duty to ransom Christians.[143]

Despite this, slavery persisted due to a steady source of non-Christians, albeit with stable prices.[144][145]

Socio-economic

Agriculture was the main basis of taxation and the state sought to bind everyone to land for productivity[146] The emperor held the largest landownership, with senators after that; Local city councillors were typically the richest in their respective areas, though there would be a noticeable disparity between smaller and larger towns.[147] In an economic sense, a middle class existed, comprising merchants, smaller landowners, and artisans, yet it never coalesced as a distinct class.[140] Most lands consisted of small and medium-sized lots, with family farms serving as the primary source of agriculture.[148] The status of the coloni—once referred to as proto-serfs—were free citizens and remains a subject of historical debate.[149] Slaves would have been rare after the 7th century, primarily urban, with their socio-economic status tied principally to their masters.[150]

In 741, marriage had become a Christian institution, and no longer a private contract.[151] Monogamy had been a Roman definition of marriage, but Christianity introduced a prohibition on divorce and sexual relations outside of marriage, bringing a change in power relations with slavery.[152] Marriage was considered an institution to sustain the population, transfer property rights, support the elderly family, and the Empress Theodora had additionally said it was needed to restrict sexual hedonism.[153] Women usually married at ages 15–20, and were used as a way to connect men and create economic benefit among families.[154] The societal norm dictated that women should bear up to six children, yet only 2–3 were expected to survive.[155] Divorce could be done by mutual consent but would be restricted over time, such as only if joining a convent.[156]

Inheritance rights were well developed, including for all women.[157] The rights may have been what prevented the emergence of large properties and a hereditary nobility capable of intimidating the state.[150] The prevalence of widows (estimated at 20%) meant that women often controlled family assets as heads of households and businesses, contributing to the rise of some empresses to power.[158] Women were major taxpayers, landowners, and petitioners to the imperial court seeking resolution for primarily property-related disputes.[159]

Education maintained a standard and a continuation from the Hellenistic and Ancient Roman eras, and right through the Byzantine era.[160] Education was voluntary but required financial means to attend.[161]

Women

Although women shared the same socio-economic status as men, they faced legal discrimination and had limitations in economic opportunities and vocations.[162] Prohibited from serving as soldiers or holding political office, and restricted from serving as deaconesses in the Church from the 7th century, women were mostly assigned household responsibilities that were "labour-intensive".[163] They worked in professions, such as in the food and textile industry, as medical staff, in public baths, had a heavy presence in retail, and were practicing members of artisan guilds.[164] They also worked in disreputable occupations: entertainers, tavern keepers, and prostitutes, allegedly where some saints and empresses originated from.[165] (Prostitution was widespread, and attempts were made to limit it, especially during Justinian's reign under the influence of Theodora.)[166]

Women participated in public life, engaging in social events such as dancing at festivals, processions, protests, and attending the Hippodrome.[150] They played an important role in resisting imperial iconastic policies.[167] Women's rights would not be better in comparative societies, nor Western Europe or America until the 19th century.[168]

Language

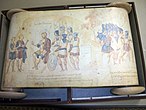

Right: The Joshua Roll, a 10th-century illuminated Greek manuscript possibly made in Constantinople (Vatican Library, Rome)

There was never an official language but Latin and Greek were the main languages.[170] During the principate, knowledge of Greek had been useful to pass the requirements to be an educated noble, and knowledge of Latin was useful for a career in the military, government, or law.[171] Latin had experienced a period of spreading from the second century BCE, and especially in the western provinces, but not as much in the eastern provinces.[172] In the east, Greek was the dominant language, a legacy of the Hellenistic period.[173] Greek was also the language of the Christian Church and trade.[174] Most of the emperors were bilingual but had a preference for Latin in the public sphere for political reasons, a practice that first started during the Punic Wars.[175]

Following Diocletian's reforms in the 3rd century CE, there was a decline in the knowledge of Greek in the West, with Latin reasserted as the language of power in the East.[176] Greek's influence grew, when Arcadius in 397 allowed judges to issue decisions in Greek, Theodosius II in 439 expanded its use in legal procedures, 448 the first law, and the 460s when Leo I legislated in it.[177][178] Justinian I's Corpus Juris Civilis, a compilation of mostly Roman jurists, was written almost entirely in Latin. However, the laws issued after 534, with Justinian's Novellae Constitutiones, were in Greek and Latin which marks when the government switched officially.[179] Greek for a time became diglossic with the spoken language, known as Koine (later, Demotic Greek), used alongside an older written form (Attic Greek) until Koine won out as the spoken and written standard.[180]

Latin had begun to evolve in the 4th century. It later fragmented into the incipient romance languages in the 8th century CE, following the collapse of the West with the Muslim invasions that broke the connection between speakers.[181][182] During the reign of Justinian (r. 527–565), Latin disappeared in the east though it may have lingered in the military until Heraclius (r. 610–641).[183][184] Contact with Western Europe in the 10th century revived Latin studies, and by the 11th century, knowledge of Latin was no longer unusual at Constantinople.[185]

Many other languages are attested in the Empire, not just in Constantinople but also at its frontiers.[186] They include Syriac, Coptic, Slavonic, Armenian, Georgian, Illyrian, Thracian, and Celtic who typically were the lower strata of the population and illiterate, the vast majority.[187] It was a multi-lingual state, but Greek bound everyone and the forces of assimilation would lead to less diversity of languages over time.[188]

Government and military

Governance

The government was run by the emperor, who was "above the law, within the law, and the law itself" and does not align with our modern understanding of the separation of powers.[189] The proclamations of the crowds of Constantinople, and the inaugurations of the patriarch from 457 CE, would legitimise the rule of an emperor.[190] The senate had its own identity but became an extension of the emperor's court; the Komnenian aristocracy would eventually replace the senatorial order.[191] The central government likely was at its peak power in the decade before 572.[192]

Transitions to new emperors were not always peaceful. The reign of Phocas (r. 602–610) was the first military overthrow since the third century, his reign also being one of 43 emperors violently removed.[193] This is partly because when the army was stationed closer to the capital it became more enmeshed in its politics.[194] There were nine dynasties between Heraclius in 610 and 1453, however only 30 of those 843 years was the empire not ruled by men linked by blood or kinship (largely due to the practice of co-emperorship).[195]

As a result of the Diocletianic–Constantinian reforms, the army was separate from the civil administration.[196] This remained in place until the 7th century, when it was divided into provinces, ruled by civil governors appointed by the emperor but responsible to the relevant praetorian prefect.[197] The provinces were grouped into four prefectures, and the army was being organised separately.[197] The Empire was divided into districts called themata at the end of the eight century, governed by a military commander called a strategos that oversaw the civil and military administration.[197] During the reign of Leo VI (r. 886–912), farmers and soldiers were more closely linked and is when supporting the army was woven into the tax system.[198]

Cities had their own governance. They were run by a local council, central government representatives, and their bishops.[199] The Arab destruction primarily changed this, with a decline in city councils from the 7th century but which also occurred in Italy due to the Lombard destruction.[200]

Military

Army

In the 5th century the East was fielding five armies of ~20,000 each in two army branches: stationary frontier units (limitanei) and mobile forces (comitatenses).[201] In the 6th century, Anthony Kaldellis claims the fiscally stretched Empire could only handle one major enemy at a time.[202] The Islamic conquests between 634 and 642 led to significant changes, transforming the 4th-7th centuries field forces into provincialised militia-like units with a core of professional soldiers.[203] The state shifted the burden of supporting the armies onto local populations and eventually wove them into the tax system, with provinces evolving into military regions known as themata.[204] Despite many challenges, Warren Treadgold states the field forces between 284 and 602 of the Eastern Empire were the best in the western world while Anthony Kaldellis believes during the conquest period of the Macedonian dynasty, they were the best in its history.[205]

The military structure would diversify to include militia-like soldiers tied to regions, professional thematic forces (tourmai), and imperial units mostly based in Constantinople (tagmata).[206] Foreign mercenaries also increasingly became employed, including the better-known tagma regiment, the Varangians, that guarded the emperor.[207] The defence-orientated thematic militias were gradually replaced with more specialised offensive field armies but also to counter the generals who would rebel against the emperor.[208] When the Empire was expanding, the state began to commute thematic military service for cash payments: in the 10th century, there were 6,000 Varangians, another 3,000 foreign mercenaries and when including paid and unpaid citizen soldiers, the army on paper was 140,000 (an expeditionary force was 15,000 soldiers and field armies seldom were more than 40,000).[209]

The thematic forces faded into insignificance—the government relying on the tagmata, mercenaries and allies instead—and which led to a neglect in defensive capability.[210] Mercenary armies would further fuel political divisions and civil wars that led to a collapse in the Empire's defence and resulting in significant losses such as Italy and the Anatolian heartland in the 11th century.[211] Major military and fiscal reforms under the emperors of the Komnenian dynasty after 1081 re-established a modest-sized, adequately compensated and competent army.[212] However, the costs were not sustainable and the structural weaknesses of the Komnenian approach—namely, the reliance on fiscal exemptions called pronoia—unraveled after the end of the reign of Manuel I (r. 1143–1180).[213]

Navy

The navy dominated the eastern Mediterranean and were active also on the Black Sea, the Sea of Marmara, and the Aegean.[214] Imperial naval forces were restructured to challenge Arab naval dominance in the 7th century, and would later cede its own dominance to the Venetians and Genoans in the 11th century.[215] The navy's patrols, in addition to chains of watchtowers and fire signals that warned inhabitants of threats, created the coastal defense for the Empire and were the responsibility of three themes (Cibirriote and others for the islands) and an imperial fleet that consisted of mercenaries like the Norsemen and Russians that later became Varangians.[216]

A new type of war galley, the dromon, appeared early in the sixth century.[217] A variant, the chelandion, appeared during the reign of Justinian II (r. 685–711) and it could be used to transport cavalry.[218] The galleys were oar-driven, designed for coastal navigation, and had capacity to hold 3–4 days of on-board water supply.[219] They were equipped with apparatus to deliver Greek fire in the 670s, and when Basil I (r. 867–886) developed professional marines, this kept the check on Muslim raiding through piracy.[220] They were the most advanced galleys on the Mediterranean until the 10th century development of the galeai which replaced them in the 12th century, when the word katergon became the standard word for war galley.[219]

Late era (1204–1453)

The rulers of the Empire of Nicaea that retook the capital and the Palaiologos that ruled until 1453, built on the Komnenian foundation initially with four types of military units—the Thelematarii (volunteer soldiers), Gasmouloi and the Southern Peloponnese Tzacones/Lakones (marines), and Proselontes/Prosalentai (oarsmen)—but similarly could not sustain funding a standing force, largely relying on mercenaries for soldiers and fiscal exemptions to pronoiars who provided a small force of mostly cavalry.[221] The Fleet was disbanded in 1284 and attempts were made to build it back later but Italian sea states sabotaged the effort.[222] Over time, the distinction between field troops and garrison units eventually disappeared as resources were strained.[223] The frequent civil wars further drained the Empire, now increasingly instigated by foreigners such as the Serbs and Turks to win concessions, and the emperors were dependent on mercenaries to keep control all the while dealing with the impact of the Black Death.[224] The strategy of employing mercenary Turks to fight civil wars was repeatedly used by emperors and led to the same outcome: subordination to the Turks.[225]

Diplomacy

According to Dimitri Obolensky, the preservation of civilisation in eastern Europe was due to the skill and resourcefulness of the Empire's diplomacy, and Imperial Diplomacy is one of its lasting contributions to the history of Europe.[226] The Empire's longevity has been said to be due to its aggressive diplomacy in negotiating treaties, the formation of alliances, and partnerships with the enemies of its enemies, notably seen with the Turks against the Persians or riffs between states like the Umayyads in Spain and the Aghlabids in Siciliy.[227] Diplomacy often involved long-term embassies, hosting foreign royals as potential hostages or political pawns, and overwhelming visitors with displays of wealth and power (with deliberate efforts that word of it would travel).[228] Other tools in diplomacy included political marriages, bestowing titles, bribery, differing levels of persuasion, and leveraging intelligence as attested in the ‘Bureau of Barbarians’ from the 4th century and which is likely the first foreign intelligence agency.[229]

Diplomacy in the Empire following Theodosius I (r. 379–395) contrasted sharply with that of the Roman Republic, emphasizing peace as a strategic necessity.[230] Even when it had more resources and less threats in the 6th century, the costs of defense were enormous;[231] foreign affairs had become more multi-polar, complex and interconnected;[232] further the challenges in protecting the empire's primarily agricultural income as well as numerous aggressive neighbors made avoiding war a preferred strategy.[233] Between the 4th and 8th centuries, diplomats leveraged the Empire's status as Orbis Romanus and sophistication as a state, which influenced the formation of new settlements on former Roman territories.[234] Byzantine diplomacy drew fledgling states into dependency, creating a network of international and inter-state relations (the oikouménē) dominated by the Empire, utilising Christianity as a tool.[235] This network focused on treaty-making, welcoming new rulers into the family of kings, and assimilating social attitudes, values, and institutions into what Evangelos Chrysos has called a "Byzantine Caliphate".[236] Diplomacy with the Muslim states, however, differed, as they were less open to diplomatic influence due to differences;[237] diplomacy centered on war-related matters such as hostages or the prevention of hostilities.[238]

Initially, the Empire's primary concern was defense against the vastly superior forces of Islam, which threatened its very existence.[239] However, a change in policies by emperors in the 9th and early 10th centuries laid the groundwork for future activity.[239] This change involved halting, reversing, and attacking Muslim power; cultivating relations with Armenians and Rus; and subjugating the Bulgarians.[239] The primary objective of diplomacy was survival, not conquest, and it was fundamentally defensive or as Dimitri Obolensky has claimed "defensive imperialism".[240] The Empire's strategic location and limited resources constrained its actions.[241] Telemachos Lounghis notes that diplomacy with the West became more challenging from 752/3 and later with the Crusades, as the balance of power shifted.[242] The number and nature of the Empire's neighbors also changed significantly, making the Limitrophe system (satellite states) and the principle of unbalanced power less effective and eventually abandoned.[243] By the 11th century, the Empire changed this core diplomatic principle to one of equality, and Byzantine diplomacy evolved instead to solicit and utilise the emperor's presence.[244]

Complex diplomatic maneuvering is how Michael Palaiologos managed to recover Constantinople in 1261.[245] Despite its weakened state, it was strong in statecraft and in the 13th and 14th centuries, the Empire still acted as the great power of the past, which allowed it to forge a network of alliances.[246] The now more influential Constantinople patriarch also gave the emperor credibility.[246] Militant Islam threatened the state geographically and Latin Christians challenged it economically.[247] Nikolaos Oikonomides claims despite not having a foreign service, it was its efficient foreign relations, not military or economic might, that kept the state alive in the late era.[248]

Law

In 438, the Codex Theodosianus, named after Theodosius II, codified Byzantine law. It went into force in the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire as well as in the Western Roman Empire. It summarised the laws and gave direction on interpretation. In 529, Justinian appointed a commission to revise and codify the law into the "Corpus Juris Civilis", or the Justinian Code. In 534, the Corpus was updated and, along with the enactments promulgated by Justinian after 534, formed the system of law used for most of the rest of the Byzantine era.[249] The Corpus forms the basis of civil law of many modern states.[250] It was Tribonian, a notable jurist, who supervised the Corpus Juris Civilis. Justinian's reforms had a clear effect on the evolution of jurisprudence, with his Corpus becoming the basis for revived Roman law in the Western world, while Leo III's Ecloga influenced the formation of legal institutions in the Slavic world.[251]

In the 10th century, Leo VI achieved the complete codification of Byzantine law in Greek. This monumental work of 60 volumes became the foundation of all subsequent Byzantine law and is still studied today.[252] Leo also reformed the administration of the empire, redrawing the borders of the administrative subdivisions (the themata, or "themes") and tidying up the system of ranks and privileges, as well as regulating the behaviour of the various trade guilds in Constantinople. Leo's reform did much to reduce the previous fragmentation of the empire, which henceforth had one centre of power, Constantinople.[253] The increasing military success of the empire greatly enriched and gave the provincial nobility more power over the peasantry, who were essentially reduced to a state of serfdom.[254]

Attested in orations by Themistius from 364 CE, and later codified in law by Justinian, the emperor was regarded as nomos empsychos, the "living law", both lawgiver and administrator.[255][256] This is a characterisation that is commonly used in modern scholarship to distinguish the Byzantine emperors from earlier Roman emperors, but it is now understood that this idea originated with the Julio-Claudian dynasty.[257][258]

Flags and insignia

For most of its history, the Byzantine Empire did not know or use heraldry in the West European sense. Various emblems (Greek: σημεία, sēmeia; sing. σημείον, sēmeion) were used on official occasions and for military purposes, such as banners or shields displaying various motifs such as the cross or the labarum. The use of the cross and images of Christ, the Virgin Mary and various saints is also attested on seals of officials, but these were personal rather than family emblems.[259]

Economy

The Byzantine economy was among the most advanced in Europe and the Mediterranean for many centuries. Europe, in particular, could not match Byzantine economic strength until late in the Middle Ages. Constantinople operated as a prime hub in a trading network that at various times extended across nearly all of Eurasia and North Africa, in particular as the primary western terminus of the famous Silk Road. Until the first half of the 6th century and in sharp contrast with the decaying West, the Byzantine economy was flourishing and resilient.[260]

The Plague of Justinian and the Arab conquests represented a substantial reversal of fortunes contributing to a period of stagnation and decline. Isaurian reforms and Constantine V's repopulation, public works and tax measures marked the beginning of a revival that continued until 1204, despite territorial contraction.[261] From the 10th century until the end of the 12th, the Byzantine Empire projected an image of luxury and travellers were impressed by the wealth accumulated in the capital.[262]

The Fourth Crusade resulted in the disruption of Byzantine manufacturing and the commercial dominance of the Western Europeans in the eastern Mediterranean, events that amounted to an economic catastrophe for the empire.[262] The Palaiologoi tried to revive the economy, but the late Byzantine state did not gain full control of either the foreign or domestic economic forces. Gradually, Constantinople also lost its influence on the modalities of trade and the price mechanisms, and its control over the outflow of precious metals and, according to some scholars, even over the minting of coins.[263]

The government attempted to exercise formal control over interest rates and set the parameters for the activity of the guilds and corporations, in which it had a special interest. The emperor and his officials intervened at times of crisis to ensure the provisioning of the capital, and to keep down the price of cereals. Finally, the government often collected part of the surplus through taxation, and put it back into circulation, through redistribution in the form of salaries to state officials, or in the form of investment in public works.[264]

One of the economic foundations of Byzantium was trade, fostered by the maritime character of the empire. Textiles must have been by far the most important item of export; silks were certainly imported into Egypt and appeared also in Bulgaria, and the West.[265] The state strictly controlled internal and international trade, and retained the monopoly of issuing coinage, maintaining a durable and flexible monetary system adaptable to trade needs.[264]

Daily life

Cuisine

Byzantine culture was initially the same as Late Greco-Roman, but over the following millennium of the empire's existence, it slowly changed into something more similar to modern Balkan and Anatolian culture. The cuisine still relied heavily on the Greco-Roman fish-sauce condiment garos, but it also contained foods still familiar today, such as the cured meat pastirma (known as "paston" in Byzantine Greek),[266][267][268] baklava (known as koptoplakous κοπτοπλακοῦς),[269] tiropita (known as plakountas tetyromenous or tyritas plakountas),[270] and the famed medieval sweet wines (Malvasia from Monemvasia, Commandaria and the eponymous Rumney wine). Retsina, wine flavoured with pine resin, was also drunk, as it still is in Greece today, producing similar reactions from unfamiliar visitors; "To add to our calamity the Greek wine, on account of being mixed with pitch, resin, and plaster was to us undrinkable", complained Liutprand of Cremona, who was the ambassador sent to Constantinople in 968 by the German Holy Roman Emperor Otto I.[271] The garos fish sauce condiment was also not much appreciated by the unaccustomed; Liutprand of Cremona described being served food covered in an "exceedingly bad fish liquor."[271] The Byzantines also used a soy sauce-like condiment, murri, a fermented barley sauce, which, like soy sauce, provided umami flavouring to their dishes.[272][273]

Recreation

Byzantines were avid players of tavli (Byzantine Greek: τάβλη), a game known in English as backgammon, which is still popular in former Byzantine realms and still known by the name tavli in Greece.[274] Byzantine nobles were devoted to horsemanship, particularly tzykanion, now known as polo. The game came from Sassanid Persia, and a Tzykanisterion (stadium for playing the game) was built by Theodosius II inside the Great Palace of Constantinople. Emperor Basil I excelled at it; Emperor Alexander died from exhaustion while playing, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos was injured while playing with Tatikios, and John I of Trebizond died from a fatal injury during a game.[275][276] Aside from Constantinople and Trebizond, other Byzantine cities also featured tzykanisteria, most notably Sparta, Ephesus, and Athens, an indication of a thriving urban aristocracy.[277] The game was introduced to the West by crusaders, who developed a taste for it particularly during the pro-Western reign of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos. Chariot races were popular and held at hippodromes across the empire. There were initially four major factions in chariot racing, differentiated by the colour of the uniform in which they competed; the colours were also worn by their supporters. These were the Blues (Veneti), the Greens (Prasini), the Reds (Russati), and the Whites (Albati), although by the Byzantine era, the only teams with any influence were the Blues and Greens. Emperor Justinian I was a supporter of the Blues.

Arts

Architecture

Influences from Byzantine architecture, particularly in religious buildings, can be found in diverse regions from Egypt and Arabia to Russia and Romania. Byzantine architecture is known for the use of domes, and pendentive architecture was invented in the Byzantine Empire. In contrast to the basilica plans favored in medieval Western European churches, Byzantine churches usually had more centralized ground plans, such as the cross-in-square plan deployed in many Middle Byzantine churches.[278] It also often featured marble columns, coffered ceilings and sumptuous decoration, including the extensive use of mosaics with golden backgrounds. Byzantine architects used marble mostly as interior cladding, in contrast to the structural roles it had for the Ancient Greeks. They used mostly stone and brick, and also thin alabaster sheets for windows. Mosaics were used to cover brick walls and any other surface where fresco would not resist. Good examples of mosaics from the proto-Byzantine era are in Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki (Greece), the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and the Basilica of San Vitale, both in Ravenna (Italy), and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Christian liturgies were held in the interior of the churches, the exterior usually having little to no ornamentation.[279][280]

-

Christ as the Good Shepherd; c. 425–430; mosaic; width: c. 3 m; Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (Ravenna, Italy)[281]

-

Diptych Leaf with a Byzantine Empress; 6th century; ivory with traces of gilding and leaf; height: 26.5 cm (10.4 in); Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)[282]

-

Collier; late 6th–7th century; gold, an emerald, a sapphire, amethysts and pearls; diameter: 23 cm (9.1 in); from a Constantinopolitan workshop; Antikensammlung Berlin (Berlin, Germany)[283]

Art

| Byzantine culture |

|---|

|

Surviving Byzantine art is mostly religious and with exceptions at certain periods is highly conventionalised, following traditional models that translate carefully controlled church theology into artistic terms. Painting in fresco, illuminated manuscripts and on wood panels and, especially in earlier periods, mosaics were the main media, and figurative sculpture was very rare except for small carved ivories. Manuscript painting preserved to the end some of the classical realist tradition that was missing in larger works.[284] Byzantine art was highly prestigious and sought-after in Western Europe, where it maintained a continuous influence on medieval art until near the end of the period. This was especially so in Italy, where Byzantine styles persisted in modified form through the 12th century, and became formative influences on Italian Renaissance art. However few incoming influences affected the Byzantine style. With the expansion of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Byzantine forms and styles spread throughout the Orthodox world and beyond.[285]

Literature

Byzantine literature concerns all Greek literature from the Middle Ages.[286] Although the Empire was linguistically varied, the vast majority of extant texts are in medieval Greek,[287] albeit in two diglossic variants: a scholarly form based on Attic Greek, and a vernacular based on Koine Greek.[288] Most contemporary scholars consider all medieval Greek texts to be literature,[289] but some offer varying constraints.[290] The literature's early period (c. 330–650) was dominated by the competing cultures of Hellenism, Christianity and Paganism.[291] The Greek Church Fathers—educated in an Ancient Greek, rhetoric tradition—sought to synthesize these influences.[286] Important early writers include John Chrysostom, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Procopius, all of whom aimed to reinvent older forms to fit the empire.[292] Theological miracle stories were particularly innovative and popular;[292] the Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Apophthegmata Patrum) were copied in practically every Byzantine monastery.[293] During the subsequent Byzantine Dark Ages (c. 650–800), most literature ceased, although some important theologians were active, such as Maximus the Confessor, Germanus I of Constantinople and John of Damascus.[292]

The subsequent Encyclopedism period (c. 800–1000) saw a renewed proliferation of literature and revived the earlier Hellenic-Christian synthesis.[286] Works by Homer, Ancient Greek philosophers and tragedians were translated, while hagiography was heavily reorganized.[292] After an early flowering of monastic literature, there was a dearth until Symeon the New Theologian in the late 10th-century.[292] A new generation (c. 1000–1250), including Symeon, Michael Psellos and Theodore Prodromos, rejected the Encyclopedist emphasis on order, and were interested in individual-focused ideals variously concerning mysticism, authorial voice, heroism, humor and love.[294] This included the Hellenistic-inspired Byzantine romance and Chivalric approaches in rhetoric, historiography and the influential epic Digenes Akritas.[292] The empire's final centuries saw a renewal of hagiography and increased Western influence, leading to mass Greek to Latin translations.[295] Authors such as Gemistos Plethon and Bessarion exemplified a new focus on human vices alongside the preservation of classical traditions, which greatly influenced the Italian Renaissance.[295]

Music

The ecclesiastical forms of Byzantine music—composed to Greek texts as ceremonial, festival, or church music[297]—are today the most well-known forms. Ecclesiastical chants were a fundamental part of this genre. Greek and foreign historians agree that the ecclesiastical tones and in general the whole system of Byzantine music is closely related to the ancient Greek system.[298] It remains the oldest genre of extant music, of which the manner of performance and (with increasing accuracy from the 5th century onwards) the names of the composers, and sometimes the particulars of each musical work's circumstances, are known.

The 9th-century Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh, in his lexicographical discussion of instruments, cited the lyra (lūrā) as the typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the urghun (organ), shilyani (probably a type of harp or lyre) and the salandj (probably a bagpipe).[299] The first of these, the early bowed stringed instrument known as the Byzantine lyra, came to be called the lira da braccio,[300] in Venice, where it is considered by many to have been the predecessor of the contemporary violin, which later flourished there.[301] The bowed "lyra" is still played in former Byzantine regions, where it is known as the Politiki lyra (lit. 'lyra of the City', i.e. Constantinople) in Greece, the Calabrian lira in southern Italy, and the lijerica in Dalmatia. The water organ originated in the Hellenistic world and was used in the Hippodrome during races.[302][303] A pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent by Emperor Constantine V to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks in 757. Pepin's son Charlemagne requested a similar organ for his chapel in Aachen in 812, beginning its establishment in Western church music.[303] The aulos was a double-reeded woodwind like the modern oboe or Armenian duduk. Other forms include the plagiaulos (πλαγίαυλος, from πλάγιος "sideways"), which resembled the flute,[304] and the askaulos (ἀσκός askos – wineskin), a bagpipe.[305] Bagpipes, also known as dankiyo (from ancient Greek: angion (Τὸ ἀγγεῖον) "the container"), had been played even in Roman times and continued to be played throughout the empire's former realms through to the present. (See Balkan Gaida, Greek Tsampouna, Pontic Tulum, Cretan Askomandoura, Armenian Parkapzuk, and Romanian Cimpoi.) The modern descendant of the aulos is the Greek Zourna. Other instruments used in Byzantine music were the Kanonaki, Oud, Laouto, Santouri, Tambouras, Seistron (defi tambourine), Toubeleki, and Daouli.

12th-century renaissance

During the 12th century, there was a revival in mosaic, and regional schools of architecture began producing many distinctive styles that drew on a range of cultural influences.[306] In this period, the Byzantines provided their model of early humanism as a renaissance of interest in classical authors. In Eustathius of Thessalonica, Byzantine humanism found its most characteristic expression.[307] In philosophy, there was a resurgence of classical learning not seen since the 7th century, characterised by a significant increase in the publication of commentaries on classical works.[308] Besides, the first transmission of classical Greek knowledge to the West occurred during the Komnenian period.[309] In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the Komnenian period was one of the peaks in Byzantine history,[310] and Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in size, wealth, and culture.[311] There was a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy, as well as an increase in literary output in vernacular Greek.[308] Byzantine art and literature held a pre-eminent place in Europe, and the cultural impact of Byzantine art on the West during this period was enormous and of long-lasting significance.[309]

Science and medicine

Byzantine science played an important and crucial role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy.[312][313] Many of the most distinguished classical scholars held high office in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[314]