Sheldon Dick

Sheldon Dick | |

|---|---|

Sheldon Dick, photographed by Janina Lester, 1939. | |

| Born | 1906 |

| Died | May 12, 1950 (aged 43–44) |

Sheldon Dick (1906–1950) was an American publisher, literary agent, photographer, and filmmaker. He was a member of a wealthy and well-connected industrialist family, and was able to support himself while funding a series of literary and artistic endeavors. He published a book by poet Edgar Lee Masters, and made a documentary about mining that has been of interest to scholars. Dick is best known for the photographs he took on behalf of the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression, and for the violent circumstances of his death.

Early life

[edit]Sheldon Dick was the son of Albert Blake Dick, a wealthy manufacturer of mimeograph machines in Chicago, and Mary Henrietta Dick.[1] He married Dorothy Michelson, the 21-year-old daughter of scientist Albert Abraham Michelson, in 1927, shortly before Dick began studies at Corpus Christi College at Cambridge University.[2] On returning to the United States, the couple lived in New York; their daughter, also named Dorothy, was born shortly thereafter.

The marriage was brief. Mrs. Dick filed for divorce in April 1932, and stated in her suit that the couple had been separated for a year. The divorce was concluded within a day, and she received custody of the child.[3]

Dick was active as a publisher at the time, working with another minor publisher, C. Louis Rubsamen.[4] Only one volume bore his name as an imprint: a book of poems, The Serpent in the Wilderness, by Edgar Lee Masters, published in a fine-press limited edition in 1933.[5] It was large (8½ by 12 inches) and made with obvious attention to detail, but with some mistakes, the worst of which was the accidental binding of manuscript pages into some copies; the reception was mixed. A positive review in The New York Times describes the physical book as "an attractive piece of work."[6] The book sold slowly, despite a brief spike caused by the Times review, and made no profit, and a trade edition, which Dick and Masters had discussed, never materialized, partly because Dick had indicated in promotional material that there would not be one.[7] Masters biographer Herbert K. Russell blames the book's failure in part on Dick's "poor judgment."

Dick married Mary Lee Burgess in 1933; she would later assist in his documentary work. His first recorded activity as a photographer took place around this time, shortly after his failure in publishing; he took photographs for a book on Mexico, published in 1935.[8] The book was not well-received, however, and a review states that "The group of photographs adds little to the volume."[9]

With the FSA

[edit]

Roy Stryker, head of the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration, collected a large group of photographers in the mid-1930s, including well-known artists like Walker Evans and many who were far less experienced, with the goal of documenting the times and the nation itself. In a 1965 interview, Stryker remembers that Dick originally was introduced to him through his contacts in the publishing world:

Henry Lester was a partner of Willard Morgan in the early days of their book publishing. And Sheldon Dick was a rich man's son and he had a desire to do things, and I went up one time and they wanted to know if I would take Sheldon down to Washington on more or less a dollar a year, he would like to work, and I agreed to it.[10]

Dick's wealth allowed him to provide his own funding, and gave him an independence the other photographers lacked. Stryker attempted to provide some guidance for the kind of photographs he was looking for, writing to Dick, "It is terribly important that you in some way try to show the town against this background of waste piles and coal tipples. In other words, it is a coal town and your pictures must tell it."[11] Instead, many of Dick's photographs are interiors, bars, and images of ordinary life. Critic Collen McDannel has pointed out that, particularly in regard to his treatment of religion, Dick's work is different from most of the FSA file. Because of his composition of images of the poor surrounded by religious items and by ordinary household objects (objects not in themselves indicating poverty), Dick's photographs are less politically clear than those of the other FSA photographers. His composition "transgresses common assumptions about men and religion and therefore appears to be less 'documentary.'"[12]

Dick worked relatively briefly for the FSA, in 1937 and 1938. He supported himself, submitting his photographs for payment of one dollar a year, but Stryker soon terminated his work anyway.[13] In the 1965 interview, Stryker says, "I went through [his albums of prints] twice, the pictures were lousy, just plain lousy [. . .] It didn't work out. He tried two or three other things for us and it didn't work." During the period of his association, however, he travelled as widely and submitted as many photographs as the full-time employees. Because Dick was not a full-time employee of the FSA, his travels are not well documented, but they can be inferred from the photographs he took.[14] Some of the greatest concentrations of surviving images come from a few documentable trips over the two years of Dick's work:

-

In January and February 1937, Dick photographed the Flint Sit-Down Strike for the FSA. Many of his photographs, like this one, are of ordinary life during the strike.

-

In July 1938, Dick was in Baltimore, taking photographs of poor black and white neighborhoods.

-

This photograph of a homemade tractor came from an August, 1938 trip to FSA client farmers in Berks County, Pennsylvania.

-

That September, Dick took photographs of damage from the New England Hurricane of 1938 in Connecticut (where this photograph of a destroyed tobacco barn was taken) and Massachusetts.

-

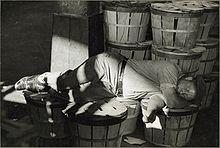

A number of images exist of the Lancaster County, Pennsylvania area, dated "1938?." The description filed with this photograph includes the note, "Notice the Amish boy on the extreme left."[15]

-

Dick's images of Pennsylvania mining towns, including this one of a bar in Gilberton (also dated "1938?"), focus on everyday activities, household living and items, and the mines themselves.

Men and Dust

[edit]One of Dick's last assignments for Stryker was a trip to the mining towns surrounding Joplin, Missouri (known as the "tri-state area").[16] He decided to return to the area to make a documentary film about the effects of silicosis on the region, but did not receive approval for the project from the FSA. Dick evidently decided to fund and direct the film himself.[17]

The result was a 16½-minute documentary film, narrated by the actor Will Geer, and consisting of both moving images and Dick's photographs of the region and its people.[18] The film, titled Men and Dust, was released in conjunction with the Association of Documentary Film Producers in New York; Lee Dick, his wife, is credited as producer under the aegis of Dial Films.[19] The score, by Fred Stewart (an actor), and narration included both informational and more suggestive narration; a comment by Paul Bowles on the film's use of sound provides a useful description:

One does not remember any music as such, but rather a constant sound of human voices, talking, singing, or humming. The idea of the possibility of human ascendancy over the deplorable conditions shown is thus made more vivid.[20]

Dick's film proved to be his most influential effort; it is cited in modern scholarship on the region's history, and his photographs of the miners and their families were displayed in a New York gallery to positive reviews.[21] Film scholar William Alexander, documenting films of the American left wing, has said that Men and Dust is "affecting and powerful" through its "mind-jogging changes of stance."[22] On December 18, 2013, the U.S. Librarian of Congress entered the film onto the National Film Registry, a list of American films the Librarian deems worthy of preservation in perpetuity.[23][24]

Dick and Stewart collaborated on another film, Day after Day, released later in 1940. The film, written and photographed by Dick and with narration by Storrs Haynes, depicts the efforts of a community nursing service operated by the Henry Street Settlement in New York.[25]

Death

[edit]In 1950 Dick was married to his third wife, Elizabeth Durand Dick. After working as a literary agent in the early 1940s, he was retired (though only 44) and living in Greens Farms, Westport, Connecticut. Early on the morning of May 12 of that year, Dick telephoned the police and said, "We have just killed ourselves. Send an officer right away."[26] Both were dead of gunshot wounds to the head when the police arrived; both shootings were ascribed to Dick. The New York Times reported that, "Other than the 'temporary insanity' theory advanced by [the medical examiner], investigators were unable to establish a motive for the shooting."

The shooting colored what sparse legacy his FSA work had left him. Colleen McDannell says that, because of it, "Dick was the most infamous of the FSA photographers."[13] Stryker connects it to his sense of the pattern of Dick's life: "He shot himself, or he shot his wife, and one of the kids and himself. [. . .] He never had a chance to be himself. It was one of the worst cases I've ever known in my experience of the wealthy son who couldn't get away from it."[27] Of course, Stryker's memory is poor, as Dick's children were unharmed.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Why S. Dick Wed Suddenly," The New York Times, September 29, 1927; "Mrs. Albert Blake Dick" (obituary), The New York Times, September 27, 1944.

- ^ "Dorothy Michelson Surprises by Wedding," The New York Times, September 29, 1927.

- ^ "Wife Sues Sheldon Dick," The New York Times, April 6, 1932; "Divorces Sheldon Dick," The New York Times, April 7, 1932.

- ^ "Books and Authors," The New York Times, October 9, 1932.

- ^ A note on the endpaper reads, "This edition consists of 400 numbered copies, of which 365 are for sale, numbers 1 to 84 inclusive, containing holograph manuscript. The book was made under the supervision of Vrest Orton & Ray Nash, and printed at the Marchbanks press on papier de Rives in Baskerville type." Edgar Lee Masters, The Serpent in the Wilderness (New York: S. Dick, 1933).

- ^ P. H., "A New Book of Poems by Edgar Lee Masters," The New York Times, August 6, 1933.

- ^ Herbert K. Russell,Edgar Lee Masters: A Biography (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 293-294.

- ^ Edith Mackie and Sheldon Dick, Mexican Journey: An Intimate Guide to Mexico (New York: Dodge Publishing Company, 1935).

- ^ Robert Spiers Benjamin, "Mexican Journey," The New York Times, September 27, 1936.

- ^ Richard Doud, "Interview with Roy Stryker at the Artist's home in Montrose, Colorado, January 23, 1965," Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; online transcript.

- ^ Alan Trachtenberg, "From Image to Story: Reading the File," Documenting America: 1935-1943, ed. Carl Fleischhauer and Beverly Brannan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 62.

- ^ Colleen McDannell, Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 40.

- ^ a b McDannell, 39.

- ^ McDannell makes this observation (39).

- ^ Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Archive, Call # LC-USF34-040326-D, online version.

- ^ See the Doud interview for Stryker's memory of this trip. Stryker mentions Dick's interest in making a film, but did not appear to know that it had been completed. None of the photographs from the tri-state trip survive in the Library of Congress's collections.

- ^ M. Keith Booker, Film and the American Left: A Research Guide (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999), 77-78.

- ^ Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner, "'The Street of Walking Death': Silicosis, Health, and Labor in the Tri-State Region, 1900-1950," The Journal of American History, Vol. 77, No. 2. (1990), 539.

- ^ Bosley Crowther, "Onward March the Documentaries," The New York Times, February 4, 1940. For the formal credits, see the film's entry at the British Film Institute database, online.

- ^ Timothy Mangan and Irene Herrmann, eds., Paul Bowles on Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 25.

- ^ For the film, see Markowitz and Rosner. For the photographs, see Howard Devree, "A Reviewer's Notebook," The New York Times, May 21, 1939. Devree said of the photographs, "These highly-moving documents [. . .] deserve a wide audience."

- ^ Alexander, Film on the Left, quoted in Booker, 78.

- ^ "25 U.S. Films Deemed Essential to Preserve," Moving Image Archive News, posted December 20, 2013 online

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ Rick Prelinger, The Field Guide to Sponsored Films (San Francisco: National Film Preservation Foundation, 2006), entry #106, p. 25; PDF version Archived 2008-01-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Sheldon Dick Kills Wife and Himself," The New York Times,May 13, 1950.

- ^ Doud, Interview.

External links

[edit]- Men and Dust essay [1] by Adrianne Finelli on the National Film Registry website

- Sheldon Dick at IMDb

- Photographs from the FSA at the Library of Congress. Contains records of all of Dick's 378 surviving photographs for the FSA and digital versions of many of them. Linked directly here.

![A number of images exist of the Lancaster County, Pennsylvania area, dated "1938?." The description filed with this photograph includes the note, "Notice the Amish boy on the extreme left."[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Sheldon_Dick_Lancaster_school.jpg/158px-Sheldon_Dick_Lancaster_school.jpg)