Slavery in Syria

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

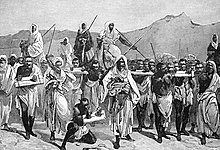

Slavery existed in the territory of the modern state of Syria until the 1920s.

Syria was one of the destinations of the Red Sea slave trade and the Indian Ocean slave trade of enslaved Africans until the late 19th century. During the Armenian genocide in 1915–1923, many Armenians were enslaved by Muslims in Ottoman Syria and Iraq, many of whom where liberated when the areas was conquered by the British during the first world war. Slavery was formally abolished in Syria by the French colonial authorities in 1931. Many members of the Afro-Syrian minority are descendants of the former slaves.

In the 21st century, Islamic terrorists again practiced slavery in areas under their control in Syria and Iraq.

Background

[edit]Present-day Syria was historically a part of many different states and cultures. The institution of slavery in the region of the later Iraq was reflected in the institution of slavery in the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661) slavery in the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), slavery in the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), slavery in the Fatimid Caliphate, slavery in the Mamluk Sultanate (1260–1516) and finally slavery in the Ottoman empire.

Ottoman Syria (1516–1918)

[edit]Slave trade

[edit]Syria both exported and imported slaves. There was a centuries old export of Syrian girls. Ibn Battuta met a Syrian Arab Damascene girl who was a slave of a black African governor in Mali in the 14th-century. Ibn Battuta engaged in a conversation with her in Arabic.[1][2][3][4][5] The black man was a scholar of Islam and his name was Farba Sulayman.[6][7] Syrian girls were trafficked from Syria to Saudi Arabia right before World War II and married to legally bring them across the border but then divorced and given to other men. A Syrian Dr. Midhat and Shaikh Yusuf were accused of engaging in this traffic of Syrian girls to supply them to Saudis.[8][9]

A major slave route to Ottoman Syria was that of African slaves trafficked from the Red Sea slave trade to Jeddah, and by caravan via the Hajj pilgrime passage from Mecca over the desert to the slave market i Damascus in Syria, which received about 200 slaves annually.[10]

The slave market in Damascus was held annually when the pilgrims returned home to Damascus from Hajj and the slave market of Mecca.[11] A Western traveller described the Damascus slave market in the 1870s as smaller than those of Constantinople and Cairo, but that in contrast to them it was held openly and not hidden away from foreigners, and that he witnessed the sale of African women and boy eunuchs as house slaves.[12]

One slave route to Ottoman Syria was the Indian Ocean slave trade by way of Ottoman Iraq.

In 1847, the British consulate in Baghdad reported:

The average import of slaves into Bussorah is 2000 head - in some years the numbers have reached 3000, but for the year 1836, owing, it is supposed, to the discouragement which the traffic has sustained from the Imam of Muscat, no more than 1000 slaves were imported. [...] Of the slaves imported, one half is usually sent to the Muntefik town on the Euphrates, named Sook-ess-Shookh, from whence they are spread all over Southern Mesopotamia, and Eastern Syria; a quarter are exported directly to Baghdad and the remainder are disposed of in the Bussorah market.[13]

Ottoman Syria was a province close enough to Constantinople to be more affected by the official abolitionist policies to curb the slave trade initiated by the Ottoman regime during the Tanzimat Era than many other, and while the slave trade to Syria did not end, it slowed down during the late 19th-century, at least according to official reports.

After a number of regulations against the slave trade caravans from Mecca by the local governor, only sixteen slaves were officially reported to have arrived at the Damascus slave market in the year of 1880.[14]

During the Armenian genocide in 1915–1923, many Armenians, primarily women, girls and boys under the age of twelve, were enslaved by Muslims in Ottoman Syria and Iraq.[15] Throughout the genocide the men were given free licence to do as they pleased with Armenian women.[16] Armenian women and children were displayed naked in auctions in Damascus, where they were sold as sex slaves. The trafficking of Armenian women as sex slaves was an important source of income for accompanying soldiers. In Arab areas, enslaved Armenian women were sold at low prices. The German consul at Mosul reported that the maximum price for an Armenian woman was "5 piastres" (about 20 Pence Sterling at the time).[17]

Function and conditions

[edit]Female slaves were primarily used as either domestic servants, or as concubines (sex slaves), while male slaves were used in a number of tasks.

Slaves in Islam were mainly directed at the service sector – concubines and cooks, porters and soldiers – with slavery itself primarily a form of consumption rather than a factor of production.[18] The most telling evidence for this is found in the gender ratio; among slaves traded in Islamic empire across the centuries, there were roughly two females to every male.[18] Outside of explicit sexual slavery, most female slaves had domestic occupations. Often, this also included sexual relations with their masters – a lawful motive for their purchase and the most common one.[19][20]

In Ottoman Syria, it was common for wealthy people, both Muslims, Christians and Jews, to own enslaved African women used as domestic servants.[11] According to Ottoman law, non-Muslims or dhimmi were not allowed to own slaves, but this prohibition was normally not enforced, especially not in Syria and Lebanon, which had a big Christian and Jewish population. In May 1842 however, the Governor of Damascus, Najib Pasha, encouraged the Muslims to attack Christians and Jews to liberate their slaves, since sharia allowed only for Muslims to own slaves. On request from the European consuls, the Christian and Jewish communities then liberated their slaves, to avoid a violent attack from the Muslims.[11] This parcial emancipation did however not affect the people enslaved by the Muslims however.

In the 1870s, it was reported that there was about 5000 African slaves (women or boys) in Damascus alone, the majority of them women, and about 100 Circassian slave women imported each year. [21]

Activism against slave trade

[edit]The British liberated many enslaved Armenians when the occupied Ottoman Syria and Iraq during World War I. When the British conquered Aleppo, Deir Zor and Cilicia in 1918, many enslaved Armenian were liberated, bought free or voluntarily handed over to the British.[22]

After the truce, the Ottoman government in Constantinople ordered the local governors in the Ottoman Empire to localise (enslaved) Christian women and children and hand them over to Christian bodies.[23] Syria was de facto ruled by king Faisal I of Syria, who was a British ally and who ordered all Arabs to return (enslaved) Christian women and children to "their people".[23]

Egyptian Armenians organized squads to resque enslaved Armenians from Beduins in Syria and Mesopotamia (Iraq); one of these, led by Rupen Herian, raported that they hade liberated 533 enslaved women and children between June and August 1919.[23]

Several actors, among them the League of Nations, the British Friends of Armenia, the Syrian Armenian Relief Society and Karen Jeppe, worked to ensure the liberation of the enslaved Armenians, some of them active as late as in the 1930s.[24] In her raport to the League of Nations in Geneva in May 1927, Karen Jeppe stated that 1600 enslaved Armenians had been liberated from slavery in a five year period, foremost from Syria;[24] however, many thousands of Armenians remained in slavery.[24]

Abolition

[edit]In 1923, former Ottoman Syria was transformed in to the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon under colonial French rule. On 20 July 1931, France ratified the 1926 Slavery Convention on behalf of both Syria and Lebanon, which was enforced on 25 June 1931.[25] In 1956, Syria ratified the 1926 Slavery Convention a second time, this time as an independent nation.

Many members of the Afro-Syrian minority are descendants of the former slaves.

21st-century

[edit]For the revival of slavery in territories in Iraq and Syria occupied by the Islamic State in the 21st-century, see Slavery in 21st-century jihadism and Genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State#Sexual slavery and reproductive violence.

See also

[edit]- Afro-Syrians

- Human trafficking in Syria

- Slavery and religion

- Islamic views on slavery

- History of slavery

- History of slavery in the Muslim world

- History of concubinage in the Muslim world

- Human trafficking in the Middle East

- Kafala system

- Slavery in 21st-century jihadism

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Asia

- Slavery in Iraq

- Slavery in Mauritania

- Slavery in Oman

- Slavery in Saudi Arabia

- Slavery in Sudan

References

[edit]- ^ Fisher, Humphrey J.; Fisher, Allan G. B. (2001). Slavery in the History of Muslim Black Africa (illustrated, revised ed.). NYU Press. p. 182. ISBN 0814727166.

- ^ Hamel, Chouki El (2014). Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. Vol. 123 of African Studies. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1139620048.

- ^ Guthrie, Shirley (2013). Arab Women in the Middle Ages: Private Lives and Public Roles. Saqi. ISBN 978-0863567643.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2018). There and Back: Twelve of the Great Routes of Human History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199093564.

- ^ King, Noel Quinton (1971). Christian and Muslim in Africa. Harper & Row. p. 22. ISBN 0060647094.

- ^ Tolmacheva, Marina A. (2017). "8 Concubines on the Road: Ibn Battuta's Slave Women". In Gordon, Matthew; Hain, Kathryn A. (eds.). Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0190622183.

- ^ Harrington, Helise (1971). Adler, Bill; David, Jay; Harrington, Helise (eds.). Growing Up African. Morrow. p. 49.

- ^ Mathew, Johan (2016). Margins of the Market: Trafficking and Capitalism across the Arabian Sea. Vol. 24 of California World History Library. University of California Press. p. 71-2. ISBN 978-0520963429.

- ^ "Margins Of The Market: Trafficking And Capitalism Across The Arabian Sea [PDF] [4ss44p0ar0h0]". vdoc.pub.

- ^ Toledano, E. R. (2014). The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression: 1840-1890. USA: Princeton University Press. p. 228-230

- ^ a b c Harel, Y. (2010). Syrian Jewry in Transition, 1840-1880. Storbritannien: Liverpool University Press. 104

- ^ Knox, T. W. (1875). Backsheesh! Or Life and Adventures in the Orient. USA: A. D. Worthington & Col. 290-292

- ^ Issawi, C. (1988). The Fertile Crescent, 1800-1914: A Documentary Economic History. Storbritannien: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 192

- ^ Toledano, E. R. (2014). The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression: 1840-1890. USA: Princeton University Press. p. 228-230

- ^ Looking Backward, Moving Forward: Confronting the Armenian Genocide. (2017). Storbritannien: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. 312.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. 314-5.

- ^ a b Segal, Islam's Black Slaves, 2001: p.4

- ^ Brunschvig. 'Abd; Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 13.

- ^ "The Truth About Islam and Sex Slavery History Is More Complicated Than You Think". HuffPost. 2015-08-19. Retrieved 2022-04-13.

- ^ The Anti-slavery Reporter. (1876). Storbritannien: The Society. p. 203-204

- ^ Morris, B., Ze'evi, D. (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. (n.p.): Harvard University Press. p. 312

- ^ a b c Morris, B., Ze'evi, D. (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. (n.p.): Harvard University Press. p. 313

- ^ a b c Looking Backward, Moving Forward: Confronting the Armenian Genocide. (2017). Storbritannien: Taylor & Francis. 104-106

- ^ Treaty Information Bulletin. United States Department of State · 1930. p. 10

Works cited

[edit]- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691153339.

- Segal, Ronald (2001). Islam's Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374527976.