Satyricon

A modern illustration of the Satyricon | |

| Author | Petronius |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Publisher | Various |

Publication date | Late 1st century AD |

| Publication place | Roman Empire |

The Satyricon, Satyricon liber (The Book of Satyrlike Adventures), or Satyrica,[1] is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius in the late 1st century AD, though the manuscript tradition identifies the author as Titus Petronius. The Satyricon is an example of Menippean satire, which is different from the formal verse satire of Juvenal or Horace. The work contains a mixture of prose and verse (commonly known as prosimetrum); serious and comic elements; and erotic and decadent passages. As with The Golden Ass by Apuleius (also called the Metamorphoses),[2] classical scholars often describe it as a Roman novel, without necessarily implying continuity with the modern literary form.[3]

The surviving sections of the original (much longer) text detail the bizarre exploits of the narrator, Encolpius, and his (possible) slave and catamite Giton, a handsome sixteen-year-old boy. It is the second most fully preserved Roman novel, after the fully extant The Golden Ass by Apuleius, which has significant differences in style and plot. Satyricon is also regarded as useful evidence for the reconstruction of how lower classes lived during the early Roman Empire.

Principal characters

[edit]

- Encolpius: The narrator and principal character, moderately well educated and presumably from a relatively elite background

- Giton: A handsome sixteen-year-old boy, a (possible) slave and a sexual partner of Encolpius

- Ascyltos: A friend of Encolpius, rival for the ownership of Giton

- Trimalchio: An extremely vulgar and wealthy freedman

- Eumolpus: An aged, impoverished and lecherous poet of the sort rich men are said to hate

- Lichas: An enemy of Encolpius

- Tryphaena: A woman infatuated with Giton

- Corax: A barber, the hired servant of Eumolpus

- Circe: A woman attracted to Encolpius

- Chrysis: Circe's servant, also in love with Encolpius

Synopsis

[edit]The work is narrated by its central figure, Encolpius. The surviving sections of the novel begin with Encolpius traveling with a companion and former lover named Ascyltos, who has joined Encolpius on numerous escapades. Encolpius' slave, Giton, is at his owner's lodging when the story begins.

Chapters 1–26

[edit]In the first passage preserved, Encolpius is in a Greek town in Campania, perhaps Puteoli, where he is standing outside a school, railing against the Asiatic style and false taste in literature, which he blames on the prevailing system of declamatory education (1–2). His adversary in this debate is Agamemnon, a sophist, who shifts the blame from the teachers to the parents (3–5). Encolpius discovers that his companion Ascyltos has left and breaks away from Agamemnon when a group of students arrive (6).

Encolpius then gets lost and asks an old woman for help returning home. She takes him to a brothel which she refers to as his home. There, Encolpius locates Ascyltos (7–8) and then Giton (8), who claims that Ascyltos made a sexual attempt on him (9). After raising their voices against each other, the fight ends in laughter and the friends reconcile but still agree to split at a later date (9–10). Later, Encolpius tries to have sex with Giton, but is interrupted by Ascyltos, who assaults him after catching the two in bed (11). The three go to the market, where they are involved in a convoluted dispute over stolen property (12–15). Returning to their lodgings, they are confronted by Quartilla, a devotee of Priapus, who condemns their attempts to pry into the cult's secrets (16–18).

The companions are overpowered by Quartilla, her maids, and an aged male prostitute, who sexually torture them (19–21), then provide them with dinner and engage them in further sexual activity (21–26). An orgy ensues and the sequence ends with Encolpius and Quartilla exchanging kisses while they spy through a keyhole at Giton deflowering a seven-year-old virgin girl (26).

Chapters 26–78, Cena Trimalchionis (Trimalchio's dinner)

[edit]

This section of the Satyricon, regarded by classicists such as Conte and Rankin as emblematic of Menippean satire, takes place a day or two after the beginning of the extant story. Encolpius and companions are invited by one of Agamemnon's slaves to a dinner at the estate of Trimalchio, a freedman of enormous wealth, who entertains his guests with ostentatious and grotesque extravagance. After preliminaries in the baths and halls (26–30), the guests (mostly freedmen) enter the dining room, where their host joins them.

Extravagant courses are served while Trimalchio flaunts his wealth and his pretence of learning (31–41). Trimalchio's departure to the toilet (he is incontinent) allows space for conversation among the guests (41–46). Encolpius listens to their ordinary talk about their neighbors, about the weather, about the hard times, about the public games, and about the education of their children. In his insightful depiction of everyday Roman life, Petronius delights in exposing the vulgarity and pretentiousness of the illiterate and ostentatious wealthy of his age.[citation needed][according to whom?]

After Trimalchio's return from the lavatory (47), the succession of courses is resumed, some of them disguised as other kinds of food or arranged to resemble certain zodiac signs (35). Falling into an argument with Agamemnon (a guest who secretly holds Trimalchio in disdain), Trimalchio reveals that he once saw the Sibyl of Cumae, who because of her great age was suspended in a flask for eternity (48).

Supernatural stories about a werewolf (62) and witches are told (63). Following a lull in the conversation, a stonemason named Habinnas arrives with his wife Scintilla (65), who compares jewellery with Trimalchio's wife Fortunata (67). Then Trimalchio sets forth his will and gives Habinnas instructions on how to build his monument when he is dead (71).

Encolpius and his companions, by now wearied and disgusted, try to leave as the other guests proceed to the baths, but are prevented by a porter (72). They escape only after Trimalchio holds a mock funeral for himself. The vigiles, mistaking the sound of horns for a signal that a fire has broken out, burst into the residence (78). Using this sudden alarm as an excuse to get rid of the sophist Agamemnon, whose company Encolpius and his friends are weary of, they flee as if from a real fire (78).

Chapters 79–98

[edit]Encolpius returns with his companions to the inn but, having drunk too much wine, passes out while Ascyltos takes advantage of the situation and seduces Giton (79). On the next day, Encolpius wakes to find his lover and Ascyltos in bed together naked. Encolpius quarrels with Ascyltos and the two agree to part, but Encolpius is shocked when Giton decides to stay with Ascyltos (80). After two or three days spent in separate lodgings sulking and brooding on his revenge, Encolpius sets out with sword in hand, but is disarmed by a soldier he encounters in the street (81–82).

After entering a picture gallery, he meets with an old poet, Eumolpus. The two exchange complaints about their misfortunes (83–84), and Eumolpus tells how, when he pursued an affair with a boy in Pergamon while employed as his tutor, the youth wore him out with his own high libido (85–87). After talking about the decay of art and the inferiority of the painters and writers of the age to the old masters (88), Eumolpus illustrates a picture of the capture of Troy by some verses on that theme (89).

This ends when those who are walking in the adjoining colonnade drive Eumolpus out with stones (90). Encolpius invites Eumolpus to dinner. As he returns home, Encolpius encounters Giton, who begs him to take him back as his lover. Encolpius finally forgives him (91). Eumolpus arrives from the baths and reveals that a man there (evidently Ascyltos) was looking for someone called Giton (92).

Encolpius decides not to reveal Giton's identity, but he and the poet fall into rivalry over the boy (93–94). This leads to a fight between Eumolpus and the other residents of the insula (95–96), which is broken up by the manager Bargates. Then Ascyltos arrives with a municipal slave to search for Giton, who hides under a bed at Encolpius's request (97). Eumolpus threatens to reveal him but after much negotiation ends up reconciled to Encolpius and Giton (98).

Chapters 99–124

[edit]In the next scene preserved, Encolpius and his friends board a ship, along with Eumolpus's hired servant, later named as Corax (99). Encolpius belatedly discovers that the captain is an old enemy, Lichas of Tarentum. Also on board is a woman called Tryphaena, by whom Giton does not want to be discovered (100–101). Despite their attempt to disguise themselves as Eumolpus's slaves (103), Encolpius and Giton are identified (105).

Eumolpus speaks in their defence (107), but it is only after fighting breaks out (108) that peace is agreed (109). To maintain good feelings, Eumolpus tells the story of a widow of Ephesus. At first she planned to starve herself to death in her husband's tomb, but she was seduced by a soldier guarding crucified corpses, and when one of these was stolen she offered the corpse of her husband as a replacement (110–112).

The ship is wrecked in a storm (114). Encolpius, Giton, and Eumolpus get to shore safely (as apparently does Corax), but Lichas is washed ashore drowned (115). The companions learn they are in the neighbourhood of Crotona, and that the inhabitants are notorious legacy-hunters (116). Eumolpus proposes taking advantage of this, and it is agreed that he will pose as a childless, sickly man of wealth, and the others as his slaves (117).

As they travel to the city, Eumolpus lectures on the need for elevated content in poetry (118), which he illustrates with a poem of almost 300 lines on the Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey (119–124). When they arrive in Crotona, the legacy-hunters prove hospitable.

Chapters 125–141

[edit]When the text resumes, the companions have apparently been in Crotona for some time (125). A maid named Chrysis flirts with Encolpius and brings to him her beautiful mistress Circe, who asks him for sex. However, his attempts are prevented by impotence (126–128). Circe and Encolpius exchange letters, and he seeks a cure by sleeping without Giton (129–130). When he next meets Circe, she brings with her an elderly enchantress called Proselenos who attempts a magical cure (131). Nonetheless, he fails again to make love, as Circe has Chrysis and him flogged (132).

Encolpius is tempted to sever the offending organ, but prays to Priapus at his temple for healing (133). Proselenos and the priestess Oenothea arrive. Oenothea, who is also a sorceress, claims she can provide the cure desired by Encolpius and begins cooking (134–135). While the women are temporarily absent, Encolpius is attacked by the temple's sacred geese and kills one of them. Oenothea is horrified, but Encolpius pacifies her with an offer of money (136–137).

Oenothea tears open the breast of the goose, and uses its liver to foretell Encolpius's future (137). That accomplished, the priestess reveals a "leather dildo" (scorteum fascinum), and the women apply various irritants to him, which they use to prepare Encolpius for anal penetration (138). Encolpius flees from Oenothea and her assistants. In the following chapters, Chrysis herself falls in love with Encolpius (138–139).

An aging legacy-huntress named Philomela places her son and daughter with Eumolpus, ostensibly for education. Eumolpus makes love to the daughter, although because of his pretence of ill health he requires the help of Corax. After fondling the son, Encolpius reveals that he has somehow been cured of his impotence (140). He warns Eumolpus that, because the wealth he claims to have has not appeared, the patience of the legacy-hunters is running out. Eumolpus's will is read to the legacy-hunters, who apparently now believe he is dead, and they learn they can inherit only if they consume his body. In the final passage preserved, historical examples of cannibalism are cited (141).

Reconstruction of lost sections

[edit]- In the text below books refers to what modern readers would call chapters.

Although interrupted by frequent gaps, 141 sections of consecutive narrative have been preserved. These can be compiled into the length of a longer novella. The extant portions were supposedly "from the 15th and 16th books" from a notation on a manuscript found in Trau in Dalmatia in 1663 by Petit. However, according to translator and classicist William Arrowsmith,

- "this evidence is late and unreliable and needs to be treated with reserve, all the more since – even on the assumption that the Satyricon contained 16 rather than, say, 20 or 24 books – the result would have been a work of unprecedented length."[5]

Still, speculation as to the size of the original puts it somewhere on the order of a work of thousands of pages, and comparisons for length range from Tom Jones to In Search of Lost Time. The extant text runs to 140 pages in the Arrowsmith edition. The complete novel must have been considerably longer, but its true length cannot be known.

Statements in the extant narrative allow the reconstruction of some events that must have taken place earlier in the work. Encolpius and Giton have had contact with Lichas and Tryphaena. Both seem to have been lovers of Tryphaena (113) at a cost to her reputation (106). Lichas' identification of Encolpius by examining his groin (105) implies that they have also had sexual relations. Lichas' wife has been seduced (106) and his ship robbed (113).

Encolpius states at one point,

- "I escaped the law, cheated the arena, killed a host" (81).

To many scholars, that suggests Encolpius had been condemned for a crime of murder, or more likely he simply feared being sentenced, to fight to his death in the arena. The statement probably is linked to an earlier insult by Ascyltos (9), who called Encolpius a "gladiator". One scholar speculates that Encolpius had been an actual gladiator rather than a criminal, but there is no clear evidence in the surviving text for that interpretation.[6](pp 47–48)

A number of fragments of Petronius's work are preserved in other authors. Servius cites Petronius as his source for a custom at Massilia of allowing a poor man, during times of plague, to volunteer to serve as a scapegoat, receiving support for a year at public expense and then being expelled.[7] Sidonius Apollinaris refers to "Arbiter", by which he apparently means Petronius's narrator Encolpius, as a worshipper of the "sacred stake" of Priapus in the gardens of Massilia.[8] It has been proposed that Encolpius's wanderings began after he offered himself as the scapegoat and was ritually expelled.[6](pp 44–45) Other fragments may relate to a trial scene.[9][10]

Among the poems ascribed to Petronius is an oracle predicting travels to the Danube and to Egypt. Courtney[6] notes that the prominence of Egypt in the ancient Greek novels might make it plausible for Petronius to have set an episode there, but expresses some doubt about the oracle's relevance to Encolpius's travels,

- "since we have no reason to suppose that Encolpius reached the Danube or the far north, and we cannot suggest any reason why he should have."[6](pp 45–46)

Analysis

[edit]Date and authorship

[edit]The date of the Satyricon was controversial in 19th- and 20th-century scholarship, with dates proposed as varied as the 1st century BC and 3rd century AD.[11] A consensus on this issue now exists. A date under Nero (1st century AD) is indicated by the work's social background[12] and in particular by references to named popular entertainers.[13][14]

Evidence in the author's style and literary concerns also indicate that this was the period during which he was writing. Except where the Satyricon imitates colloquial language, as in the speeches of the freedmen at Trimalchio's dinner, its style corresponds with the literary prose of the period. Eumolpus' poem on the Civil War and the remarks with which he prefaces it (118–124) are generally understood as a response to the Pharsalia of the Neronian poet Lucan.[14][15]

Similarly, Eumolpus's poem on the capture of Troy (89) has been related to Nero's Troica and to the tragedies of Seneca the Younger,[16] and parody of Seneca's Epistles has been detected in the moralizing remarks of characters in the Satyricon.[17] There is disagreement about the value of some individual arguments but, according to S. J. Harrison, "almost all scholars now support a Neronian date" for the work.[11]

The manuscripts of the Satyricon ascribe the work to a "Petronius Arbiter", while a number of ancient authors (Macrobius, Sidonius Apollinaris, Marius Victorinus, Diomedes and Jerome) refer to the author as "Arbiter". The name Arbiter is likely derived from Tacitus' reference to a courtier named Petronius as Nero's arbiter elegantiae or fashion adviser (Annals 16.18.2). That the author is the same as this courtier is disputed. Many modern scholars accept the identification, pointing to a perceived similarity of character between the two and to possible references to affairs at the Neronian court.[18] Other scholars consider this identification "beyond conclusive proof".[19]

Genre

[edit]The Satyricon is considered one of the gems of Western literature, and, according to Branham, it is the earliest of its kind in Latin.[20] Petronius mixes together two antithetical genres: the cynic and parodic menippean satire, and the idealizing and sentimental Greek romance.[20] The mixing of these two radically contrasting genres generates the sophisticated humor and ironic tone of Satyricon.[20]

The name “satyricon” implies that the work belongs to the type to which Varro, imitating the Greek Menippus, had given the character of a medley of prose and verse composition. But the string of fictitious narrative by which the medley is held together is something quite new in Roman literature. The author was happily inspired in his devices for amusing himself and thereby transmitted to modern times a text based on the ordinary experience of contemporary life; the precursor of such novels as Gil Blas by Alain-René Lesage and The Adventures of Roderick Random by Tobias Smollett. It reminds the well-read protagonist of Joris-Karl Huysmans's À rebours of certain nineteenth-century French novels: "In its highly polished style, its astute observation, its solid structure, he could discern curious parallels and strange analogies with the handful of modern French novels he was able to tolerate."[21]

Literary and cultural legacy

[edit]Apocryphal supplements

[edit]The incomplete form in which the Satyricon survives has tantalized many readers, and between 1692 and the present several writers have attempted to round the story out. In certain cases, following a well-known conceit of historical fiction, these invented supplements have been claimed to derive from newly discovered manuscripts, a claim that may appear all the more plausible since the real fragments actually came from two different medieval sources and were only brought together by 16th- and 17th-century editors. The claims have been exposed by modern scholarship, even 21st-century apocryphal supplements.

Historical contributions

[edit]Found only in the fragments of the Satyricon is our source of information about the language of the people who made up Rome's populace. The Satyricon provides description, conversation, and stories that have become invaluable evidence of colloquial Latin. In the realism of Trimalchio's dinner party, we are provided with informal table talk that abounds in vulgarisms and solecisms which give us insight into the unknown Roman proletariat.

Chapter 41, the dinner with Trimalchio, depicts such a conversation after the overbearing host has left the room. A guest at the party, Dama, after calling for a cup of wine, begins first:

"Diēs," inquit, "nihil est. Dum versās tē, nox fit. Itaque nihil est melius quam dē cubiculō rēctā in triclīnium īre. Et mundum frīgus habuimus. Vix mē balneus calfēcit. Tamen calda pōtiō vestiārius est. Stāminātās dūxī, et plānē mātus sum. Vīnus mihi in cerebrum abiit."

—

"Daytime," said he, "is nothing. You turn around and night comes on. Then there's nothing better than going straight out of bed to the dining room. And it's been pretty cold. I could scarcely get warm in a bathtub. But a hot drink is a wardrobe in itself. I've had strong drinks, and I'm flat-out drunk. The wine has gone to my head."

Modern literature

[edit]In the process of coming up with the title of The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald had considered several titles for his book including "Trimalchio" and "Trimalchio in West Egg;" Fitzgerald characterizes Gatsby as Trimalchio in the novel, notably in the first paragraph of Chapter VII:

It was when curiosity about Gatsby was at its highest that the lights in his house failed to go on one Saturday night—and, as obscurely as it had begun, his career as Trimalchio was over.[22]

An early version of the novel, still titled "Trimalchio", was published by the Cambridge University Press.

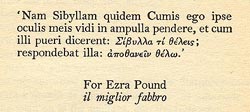

T. S. Eliot's seminal poem of cultural disintegration, The Waste Land, is prefaced by a verbatim quotation out of Trimalchio's account of visiting the Cumaean Sibyl (Chapter 48), a supposedly immortal prophetess whose counsel was once sought on all matters of grave importance, but whose grotto by Neronian times had become just another site of local interest along with all the usual Mediterranean tourist traps:

Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumīs ego ipse oculīs meīs vīdī in ampullā pendere, et cum illī puerī dīcerent: "Σίβυλλα τί θέλεις;" respondēbat illa: "ἀποθανεῖν θέλω."

Arrowsmith translates:

I once saw the Sibyl of Cumae in person. She was hanging in a bottle, and when the boys asked her, "Sibyl, what do you want?" she said, "I want to die."[23]

In Isaac Asimov's short story "All the Troubles of the World", Asimov's recurring character Multivac, a supercomputer entrusted with analyzing and finding solutions to the world's problems, is asked "Multivac, what do you yourself want more than anything else?" and, like the Satyricon's Sibyl when faced with the same question, responds "I want to die."

A sentence written by Petronius in a satyrical sense, to represent one of the many gross absurdities told by Trimalchio, reveals the cupio dissolvi feeling present in some Latin literature; a feeling perfectly seized by T. S. Eliot.

Oscar Wilde's novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, mentions "What to imperial Neronian Rome the author of the Satyricon once had been."

DBC Pierre's novel Lights Out in Wonderland repeatedly references the Satyricon.

Graphic arts

[edit]A series of 100 etchings illustrating the Satyricon was made by the Australian artist Norman Lindsay. These were included in several 20th century translations, including, eventually, one by the artist's son Jack Lindsay.

Film

[edit]In 1969 two film versions were made. Fellini Satyricon, directed by Federico Fellini, was loosely based upon the book. The film is deliberately fragmented and surreal though the androgynous Giton (Max Born) gives the graphic picture of Petronius's character. Among the chief narrative changes Fellini makes to the Satyricon text is the addition of a hermaphroditic priestess, who does not exist in the Petronian version.

In Fellini's adaptation, the fact that Ascyltos abducts this hermaphrodite, who later dies a miserable death in a desert landscape, is posed as an ill-omened event, and leads to the death of Ascyltos later in the film (none of which is to be found in the Petronian version). Other additions Fellini makes in his filmic adaptation: the appearance of a minotaur in a labyrinth (who first tries to club Encolpius to death, and then attempts to kiss him), and the appearance of a nymphomaniac whose husband hires Ascyltos to enter her caravan and have sex with her.

The other movie, Satyricon, was directed by Gian Luigi Polidoro.

Music and theatre

[edit]The Norwegian black metal band Satyricon is named after the book.

American composer James Nathaniel Holland adapted the story and wrote music for the ballet, The Satyricon.

Paul Foster wrote a play (called Satyricon) based on the book, directed by John Vaccaro at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in 1972.[24]

British director Martin Foreman wrote a play (titled The Satyricon) based on the novel. It was staged in Edinburgh in October 2022 as a co-production between Arbery Theatre and the Edinburgh Graduate Theatre Group.[25] In Foreman's adaptation the presumed author of the book, Petronius, plays an editorializing role, commenting on structural aspects of the text, such as its fragmentary nature, as well as on philosophical themes it addresses, such as 1st-century AD Roman attitudes to slavery.[26]

English translations

[edit]Over a span of more than three centuries the Satyricon has frequently been translated into English, often in limited editions. The translations are as follows. The online versions, like the originals on which they are based, often incorporate spurious supplements which are not part of the authentic Satyricon.

- William Burnaby, 1694, London: Samuel Briscoe. Includes Nodot's spurious supplement. Available online.

- Revised by Mr Wilson, 1708, London.

- Included in the edition of 1910, London, edited by Stephen Gaselee and illustrated by Norman Lindsay.

- Reprinted with an introduction by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, 1923, London.

- Revised by Gilbert Bagnani, 1964, New York: Heritage. Illustrated by Antonio Sotomayor.

- John Addison, 1736, London.

- Walter K. Kelly, 1854, in the volume Erotica: The elegies of Propertius, The Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter, and The Kisses of Johannes Secundus. London: Henry G. Bohn. Includes the supplements by Nodot and Marchena.

- Paris, 1902. Published by Charles Carrington, and ascribed by the publisher (on a loose slip of paper inserted into each copy) to Sebastian Melmoth (a pseudonym used by Oscar Wilde). Includes the Nodot supplements; these are not marked off.[27]

- reprint "in the translation attributed to Oscar Wilde", 1927, Chicago: P. Covici; 1930, Panurge Press. Available online as the translation of Alfred R. Allinson.

- Michael Heseltine, 1913, London: Heinemann; New York; Macmillan (Loeb Classical Library).

- revised by E. H. Warmington, 1969, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- William Stearns Davis, 1913, Boston: Allyn and Bacon (being an excerpt from "The Banquet of Trimalchio" in Readings in Ancient History, Vol. 2 available online with a Latin word list.)

- The Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter (1922) edited and translated by W. C. Firebaugh. Illustrated by Norman Lindsay. New York: Boni & Liveright. Includes the supplements by de Salas, Nodot, and Marchena separately marked.

- Adapted by Charles Whibley, 1927, New York.

- J. M. Mitchell, 1923, London: Routledge; New York: Dutton.

- Jack Lindsay (with the illustrations by Norman Lindsay), 1927, London: Fanfrolico Press; 1944, New York: Willey; 1960, London: Elek.

- Alfred R. Allinson, 1930, New York: The Panurge Press. (This is the same translation published in 1902 with a false attribution to Oscar Wilde.)

- Paul Dinnage, 1953, London: Spearman & Calder.

- William Arrowsmith, 1959, The University of Michigan Press. Also 1960, New York: The New American Library/Mentor.

- Paul J. Gillette, 1965, Los Angeles: Holloway House.

- J. P. Sullivan, 1965 (revised 1969, 1977, 1986), Harmondsworth, England: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044489-0.

- R. Bracht Branham and Daniel Kinney, 1996, London, New York: Dent. ISBN 0-520-20599-5. Also 1997, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21118-9 (paperback).

- P. G. Walsh, 1997, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283952-7 and ISBN 0-19-283952-7.

- Sarah Ruden, 2000, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 0-87220-511-8 (hardcover) and ISBN 0-87220-510-X (paperback).

- Frederic Raphael (Illustrated by Neil Packer), 2003, London: The Folio Society

- Andrew Brown, 2009, Richmond, Surrey: Oneworld Classics Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84749-116-9.

Français

- Laurent Tailhade, 1922, Paris: Éditions de la Sirène Gutenberg.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ S. J. Harrison (1999). Oxford Readings in the Roman Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xiii. ISBN 0-19-872174-9.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 834.

- ^ Harrison (1999). Nonetheless, Moore (101–3) aligns it with modern novels like Joyce's Ulysses and Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow.

- ^ "The Satyricon (Illustrated Edition)". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Arrowsmith, William (1959). Petronius: The Satyricon. Mentor. p. vii. ISBN 9780451003850.

- ^ a b c d Courtney, Edward (2001). A Companion to Petronius. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924594-0.

- ^ Petronius fragment 1 =

- ^ Petronius fragment 4 =

- Sidonius Apollinaris. Carmen. 23.155–157.

- ^ Petronius fragment 8 =

- Fabius Planciades Fulgentius. Expositio Vergilianae continentiae. p. 98.

- ^ Petronius fragment 14 =

- Isidore of Seville. Origines. 5.26.7.

- ^ a b Harrison (1999), p. xvi.

- ^ R. Browning (May 1949). "The Date of Petronius". Classical Quarterly. 63 (1): 12–14. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00094270. S2CID 162540839.

- ^ Henry T. Rowell (1958). "The Gladiator Petraites and the Date of the Satyricon". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 89. The Johns Hopkins University Press: 14–24. doi:10.2307/283660. JSTOR 283660.

- ^ a b K. F. C. Rose (May 1962). "The Date of the Satyricon". Classical Quarterly. 12 (1): 166–168. doi:10.1017/S0009838800011721. S2CID 170460020.

- ^ Courtney, pp. 8, 183–189

- ^ Courtney, pp. 141–143

- ^ J. P. Sullivan (1968). "Petronius, Seneca, and Lucan: A Neronian Literary Feud?". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 99. The Johns Hopkins University Press: 453–467. doi:10.2307/2935857. JSTOR 2935857.

- ^ e.g., Courtney, pp. 8–10

- ^ Harrison (2003) pages 1149–1150

- ^ a b c Branham, R. Bracht (1997-07-11). Satyrica. University of California Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-520-21118-6.

- ^ Against Nature, trans. Margaret Mauldon (Oxford, 1998), p. 26.

- ^ F. Scott Fitzgerald. (1925). The Great Gatsby, pp 119. Scribners Trade Paperback 2003 edition.

- ^ Arrowsmith, William. The Satyricon. Meridian, 1994, p. 57

- ^ "Program: "Satyricon" (1972) DOCUMENT". LaMama Archives. Archived from the original on 2023-02-18. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ^ "The Satyricon: the 2,000 year old outrageous comedy". thesatyricon.uk. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "The Satyricon : All Edinburgh Theatre.com". www.alledinburghtheatre.com. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Boroughs, Rod, "Oscar Wilde's Translation of Petronius: The Story of a Literary Hoax", English Literature in Transition (ELT) 1880-1920, vol. 38, nr. 1 (1995) pages 9-49. The 1902 translation made free use of Addison's 1736 translation, but mistakenly attributes it to Joseph Addison, the better known author and statesman who died in 1719. The bibliography is disappointing in both range and accuracy. The underlying text is very bad and turns of phrase suggest that the translation was more likely from French renderings than directly from the original Latin. Despite the publisher's slip of paper ascribing it to Oscar Wilde, the style is not good enough and Carrington could not, when challenged, produce any of the manuscript. Gaselee, Stephen, "The Bibliography of Petronius", Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, vol. 10 (1908) page 202.

Further reading

[edit]- Branham, R Bracht and Kinney, Daniel (1997) Introduction to Petronius' Satyrica pp.xiii-xxvi.

- S. J. Harrison (1999). "Twentieth-Century Scholarship on the Roman Novel". In S. J. Harrison (ed.). Oxford Readings in the Roman Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xi–xxxix. ISBN 0-19-872173-0. Archived from the original on 2006-05-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - S. J. Harrison (2003). "Petronius Arbiter". In Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth (ed.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd edition, revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1149–1150. ISBN 0-19-860641-9.

- Moore, Steven. The Novel, an Alternative History: Beginnings to 1600. Continuum, 2010.

- Bodel, John. 1999. “The Cena Trimalchionis.” Latin Fiction: The Latin Novel in Context. Edited by Heinz Hofmann. London; New York: Routledge.

- Boyce, B. 1991. The Language of the Freedmen in Petronius' Cena Trimalchionis. Leiden: Brill.

- Connors, C. 1998. Petronius the Poet: Verse and Literary Tradition in the Satyricon. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- George, P. 1974. "Petronius and Lucan De Bello Civili." The Classical Quarterly 24.1: 119–133.

- Goddard, Justin. 1994. "The Tyrant at the Table." Reflections of Nero: Culture, History, and Representation. Edited by Jaś Elsner & Jamie Masters. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Habermehl, Peter, Petronius, Satyrica 79–141. Ein philologisch–literarischer Kommentar. Band I: Satyrica 79–110. Berlin: de Gruyter. 2006.

- Habermehl, Peter, Petronius, Satyrica 79–141. Ein philologisch–literarischer Kommentar. Band II: Satyrica 111–118. Berlin: de Gruyter. 2020.

- Habermehl, Peter, Petronius, Satyrica 79–141. Ein philologisch–literarischer Kommentar. Band III: Bellum civile (Sat. 119–124). Berlin: de Gruyter. 2021.

- Highet, G. 1941. "Petronius the Moralist." Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 72: 176–194.

- Holmes, Daniel. 2008. "Practicing Death in Petronius' Cena Trimalchionis and Plato's Phaedo." The Classical Journal 104.1: 43–57.

- Jensson, Gottskalk. 2004. The Recollections of Encolpius: The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction. Groningen: Barkhuis Publishing and Groningen University Library (Ancient narrative Suppl. 2). Available online.

- Panayotakis, C.1995. Theatrum Arbitri. Theatrical Elements in Satyrica of Petronius. Leiden: Brill.

- Plaza, M. 2000. Laughter and Derision in Petronius’ Satyrica. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

- Ferreira, P., Leão, D. and C. Teixeira. 2008. The Satyricon of Petronius: Genre, Wandering and Style. Coimbra: Centro de Estudos Clássicos e Humanísticos da Universidade de Coimbra.

- Ragno, T. 2009. Il teatro nel racconto. Studi sulla fabula scenica della matrona di Efeso. Bari: Palomar.

- Rimell, V. 2002. Petronius and the Anatomy of Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sandy, Gerald. 1970. "Petronius and the Tradition of the Interpolated Narrative." Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 101: 463–476.

- Schmeling, G. 2011. A Commentary on the Satyrica of Petronius. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmeling, G. and J. H. Stuckey. 1977. A Bibliography of Petronius. Lugduni Batavorum: Brill.

- Setaioli. A. 2011. Arbitri Nugae: Petronius' Short Poems in the Satyrica. Studien zur klassischen Philologie 165. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Slater, N. 1990. Reading Petronius. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Zeitlin, F. 1971. "Petronius as Paradox: Anarchy and Artistic Integrity." Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 102: 631–684.

External links

[edit]- Satyricon at Perseus Digital Library

- Satyricon (Latin text) [1] (English translation) [2]

The Satyricon public domain audiobook at LibriVox.

The Satyricon public domain audiobook at LibriVox.- The Widow of Ephesus (Satyricon 110.6–113.4): A Grammatical Commentary by John Porter, University of Saskatchewan, with frames [3] and without frames. [4]