Valar

The Valar (['valar]; singular Vala) are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. They are "angelic powers" or "gods"[T 1] subordinate to the one God (Eru Ilúvatar). The Ainulindalë describes how some of the Ainur choose to enter the world (Arda) to complete its material development after its form is determined by the Music of the Ainur. The mightiest of these are called the Valar, or "the Powers of the World", and the others are known as the Maiar.

The Valar are mentioned briefly in The Lord of the Rings but Tolkien had developed them earlier, in material published posthumously in The Silmarillion, especially the "Valaquenta" (Quenya: "Account of the Valar"), The History of Middle-earth, and Unfinished Tales. Scholars have noted that the Valar resemble angels in Christianity but that Tolkien presented them rather more like pagan gods. Their role in providing what the characters in Middle-earth experience as luck or providence is also discussed.

Origin and acts

[edit]The creator Eru Ilúvatar first reveals to the Ainur his great vision of the world, Arda, through musical themes, as described in Ainulindalë, "The Music of the Ainur".[T 2]

This world, fashioned from his ideas and expressed as the Music of Ilúvatar, is refined by thoughtful interpretations by the Ainur, who create their own themes based on each unique comprehension. No one Ainu understands all the themes that spring from Ilúvatar. Instead, each elaborates individual themes, singing of mountains and subterranean regions, say, from themes for metals and stones. The themes of Ilúvatar's music are elaborated, and each of the Ainur add harmonious creative touches. Melkor, however, adds discordant themes: He strives against the Music; his themes become evil because they spring from selfishness and vanity, not from the enlightenment of Ilúvatar.[T 2]

Once the Music is complete, including Melkor's interwoven themes of vanity, Ilúvatar gives the Ainur a choice—to dwell with him or to enter the world that they have mutually created. The greatest of those that choose to enter the world become known as the Valar, the 'Powers of Arda', and the lesser are called the Maiar. Among the Valar are some of the most powerful and wise of the Ainur, including Manwë, the Lord of the Valar, and Melkor, his brother. The two are distinguished by the selfless love of Manwë for the Music of Ilúvatar and the selfish love that Melkor bears for himself and no other—least of all for the Children of Ilúvatar, Elves and Men.[T 2]

Melkor (later named Morgoth, Sindarin for "dark enemy") arrives in the world first, causing tumult wherever he goes. As the others arrive, they see how Melkor's presence would destroy the integrity of Ilúvatar's themes. Eventually, and with the aid of the Vala Tulkas, who enters Arda last, Melkor is temporarily overthrown, and the Valar begin shaping the world and creating beauty to counter the darkness and ugliness of Melkor's discordant noise.[T 3]

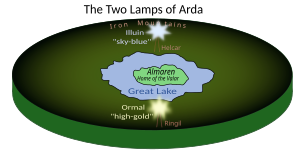

The Valar originally dwell on the Isle of Almaren in the middle of Arda, but after its destruction and the loss of the world's symmetry, they move to the western continent of Aman and found Valinor. The war with Melkor continues: The Valar realize many wonderful subthemes of Ilúvatar's grand music, while Melkor pours all his energy into Arda and the corruption of creatures like Balrogs, dragons, and Orcs. Most terrible of the early deeds of Melkor is the destruction of the Two Lamps and with them, the original home of the Valar, the Isle of Almaren. Melkor is captured and chained for many ages in the fastness of Mandos, until he is pardoned by Manwë.[T 3][T 4]

With the arrival of the Elves in the world, a new phase of the regency of the Valar begins. Summoned by the Valar, many Elves abandon Middle-earth and the eastern continent for the West, Valinor, where the Valar concentrate their creativity. There they make the Two Trees, their greatest joy because they illuminate the beauty of Valinor and delight the Elves.[T 4]

At Melkor's instigation the evil giant spider Ungoliant destroys the Trees. Fëanor, a Noldor Elf, with forethought and love, captures the light of the Two Trees in three Silmarils, the greatest jewels ever created. Melkor steals the Silmarils from Fëanor, kills his father, Finwë, chief of the Noldor in Aman, and flees to Middle-earth. Many of the Noldor, in defiance of the will of the Valar, swear revenge and set out in pursuit. This event, and the poisonous words of Melkor that foster mistrust among the Elves, leads to the exile of the greater part of the Noldor to Middle-earth: The Valar close Valinor against them to prevent their return.[T 5]

For the remainder of the First Age, the Lord of Waters, Ulmo, alone of the Valar, visits the world beyond Aman. Ulmo directly influences the actions of Tuor, setting him on the path to find the hidden city of Gondolin.[T 6] At the end of the First Age, the Valar send forth a great host of Maiar and Elves from Valinor to Middle-earth, fighting the War of Wrath, in which Melkor is defeated. The lands are changed, and the Elves are again called to Valinor.[T 7]

During the Second Age, the Valar's main deeds are the creation of Númenor as a refuge for the Edain, who are denied access to Aman but given dominion over the rest of the world. The Valar, now including even Ulmo, remain aloof from Middle-earth, allowing the rise to power of Morgoth's lieutenant, Sauron, as a new Dark Lord. Near the end of the Second Age, Sauron convinces the Númenóreans to attack Aman itself. This leads Manwë to call upon Ilúvatar to restore the world to order; Ilúvatar answers by destroying Númenor, as described in the Akallabêth.[T 8] Aman is removed from Arda (though not from the whole created world, Eä, for Elvish ships could still reach it).[T 8] In the Third Age, the Valar send the Istari (or wizards) to Middle-earth to aid in the battle against Sauron.[T 9]

The chief Valar

[edit]The names and attributes of the chief Valar, as they are described in the "Valaquenta", are listed below. In Middle-earth, they are known by their Sindarin names: Varda, for example, is called Elbereth. Men know them by many other names, and sometimes worship them as gods. With the exception of Oromë, the names listed below are not actual names but rather titles: The true names of the Valar are nowhere recorded. The males are called "Lords of the Valar", and the females are called "Queens of the Valar," or Valier. Of the known seven male and seven female Valar, there are six married pairs: Ulmo and Nienna are the only ones who dwell alone. This is evidently a spiritual rather than a physical union, as in Tolkien's later conception they do not reproduce.[T 10]

The Aratar (Quenya: Exalted), or High Ones of Arda, are the eight greatest of the Valar: Manwë, Varda, Ulmo, Yavanna, Aulë, Mandos, Nienna, and Oromë. Lórien and Mandos are brothers and are collectively called as the Fëanturi, "Masters of Spirits".[T 10]

Ilúvatar brings the Valar (and all the Ainur) into being by his thought and may therefore be considered their father. However, not all the Valar are siblings; where this is held to be so, it is because they are so "in the thought of Ilúvatar". It was the Valar who first practise marriage and later pass on their custom to the Elves; all the Valar have spouses, save Nienna, Ulmo, and Melkor. Only one such marriage among the Valar takes place within the world, that of Tulkas and Nessa after the raising of the Two Lamps.[T 10]

Lords

[edit]| Name(s) | Duties | Spouse | Dwelling-place | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manwë | King of the Valar, King of Arda, Lord of air, wind, and clouds | Varda | Atop Mount Taniquetil, the highest mountain of the world, in the domed halls of Ilmarin from where he could see right across Middle-earth | Noblest and greatest in authority, but not in power, of the Ainur; greatest of the Aratar. Observes the tidings of Middle-Earth and intervenes when necessary by use of his heralds, the Eagles of Manwë and their king, Thorondor. |

| Ulmo | Lord of Waters | —— | No fixed dwelling place: he lives in deep waters of ocean | Comes to Valinor only in dire need. A chief architect of Arda. In authority, second to Manwë. Sympathetic to the plight of the Ñoldor and delivers them hope in the form of Tuor who weds Idril and fathers Eärendil, the mariner who sails the difficult seas and arrives in Valinor to plead with the Valar on behalf of the Ñoldor. |

| Aulë | Lord of matter, Master of all crafts | Yavanna | Valinor | Creates the seven fathers of the Dwarves, who call him Mahal, the Maker. Eru is not pleased, as the stone people are not of the original theme and possess no fëa, only being able to do as the will of Aulë commands, but when Aulë lifts his hammer to smite them in repentance, they tremble upon the sight of Aulë's hammer, as Eru in that moment grants them fëa and pardons Aulë's disobedience. Eru notes the repercussions, including the love of the Dwarves' iron for Yavanna's trees. During the Music of the Ainur, Aulë's themes concern the physical things of which Arda is made; when Eru gives being to the themes of the Ainur, his music becomes the lands of Middle-earth. He created Angainor (the chain of Melkor), the Two Lamps, the aforementioned dwarves, and the vessels of the Sun and Moon. |

| Oromë [ˈorome], Araw in Sindarin, Aldaron "Lord of the Trees", Arum, Béma, Arāmē, the Great Rider | Huntsman of the Valar | Vána | Brother of Nessa. Active in the struggle against Morgoth. Renowned for his anger, the most terrible of the Valar in his wrath. Has a mighty horn, Valaróma, and a steed called Nahar. During the Years of the Trees, after most of the Valar had hidden in Aman, Oromë still hunts the Enemy in the forests of Middle-earth with Huan, Hound of the Valar. There he finds the Elves at Cuiviénen.[a] | |

| Mandos [ˈmandos], Námo [ˈnaːmo] | Judge of the Dead, Master of Doom, Chief advisor to Manwë, Keeper of the souls of elves | Vairë | Halls of Mandos | Stern and dispassionate, never forgetting a thing. Speaks the Prophecy of the North against the Noldor Elves leaving Aman, counselling that they should not be allowed to return.[b] The prophecies and judgments of Mandos, unlike Morgoth, are not cruel or vindictive by his own design. They are simply the will of Eru, and he does not speak them unless he is commanded to do so by Manwë. Only once is he moved to pity, when Lúthien sings of the grief she and her lover Beren had experienced in Beleriand. |

| Lórien [ˈloːrien], Irmo [ˈirmo] | Master of Visions and Dreams | Estë | Lórien | Named Irmo, but more commonly called Lórien, after his dwelling place. Lórien and Mandos are the Fëanturi: Masters of spirits. Lórien, the younger, is the master of visions and dreams. His gardens in the land of the Valar, where he dwells with his wife Estë, are the fairest place in the world and are filled with many spirits. All those who dwell in Valinor find rest and refreshment at the fountain of Irmo and Estë. Since he is the master of dreams, he and his servants are well aware of the hopes and dreams of the children of Eru. Olórin, or Gandalf, prior to his assignment by Manwë to a role as one of the Istari, is a Maia who long taught in the gardens of Lórien. |

| Tulkas [ˈtulkas] the Strong, Astaldo "The Brave One" | Champion of Valinor | Nessa | Not initially one of the Valar, Tulkas the Strong is "greatest in strength and deeds of prowess ... [who] came last to Arda, to aid the Valar in the first battles with Melkor".[T 10] Having joined the Valar, Tulkas is the Last of the Valar to descend into Arda, helping tip the scales against Melkor prior to the creation of the Two Lamps. Swifter on foot than any other living thing, he eschews a steed in battle. A wrestler, physically the strongest of Valar, his fist is his only weapon. He laughs in sport and in war, and even laughs in the face of Melkor. Husband of Nessa; slow to anger, but slow to forget; opposes release of Melkor after his prison sentence. |

Queens

[edit]| Name(s) | Spouse | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Varda Elentári in Quenya Elbereth Gilthoniel in Sindarin Lady of the Stars the Kindler |

Manwë | Kindles the first stars before the Ainur descend into the world; later brightens them with gold and silver dew from the Two Trees. Melkor fears and hates her the most, because she rejected him before Time. The Elvish hymn A Elbereth Gilthoniel appears in three differing forms in The Lord of the Rings.[T 13][T 14][T 15] |

| Nienna Lady of Mercy, acquainted with grief |

—— | Tutor of Olórin; weeps constantly, but not for herself; and those who hearken to her learn pity, and endurance in hope. She gives strength to those in the Hall of Mandos. Her tears are those of healing and compassion, not of sadness, and often have potency; she watered the Two Trees with her tears, and washed the filth of Ungoliant away from them once they were destroyed. She was in favour of releasing Melkor after his sentence, not being able to see his evil nature. |

| Estë [ˈeste] The Gentle "the healer of hurts and of weariness" |

Irmo | Her name means 'Rest'. "Grey is her raiment, and rest her gift." Lives with Irmo in his Gardens of Lórien in Valinor. She sleeps at day on the island in the Lake Lorellin. |

| Vairë [ˈvai̯re] the Weaver |

Mandos | She weaves the story of the world in her tapestries, which are draped all over the halls of Mandos. |

| Yavanna [jaˈvanna] Queen of the Earth Giver of Fruits |

Aulë | She is responsible for both kelvar (animals) and olvar (plants). She requested the creation of the Ents, concerned for the safety of the trees once her husband created the Dwarves. The Two Lamps were created by Aulë at Yavanna's request; their light germinated the seeds that she had planted throughout Arda. Following the destruction of the Two Lamps by Melkor and the withdrawal of the Valar to Aman, Yavanna sings into being her greatest creation, the Two Trees of Valinor. |

| Vána [ˈvaːna] Queen of Blossoming Flowers and the Ever-young |

Oromë | Younger sister of Yavanna. "All flowers spring as she passes and open if she glances upon them; and all birds sing at her coming." She dwells in gardens filled with golden flowers and often comes to the forests of Oromë. Tolkien wrote that Vána was "the most perfectly 'beautiful' in form and feature (also 'holy' but not august or sublime), representing the natural unmarred perfection of form in living things".[T 16] |

| Nessa The Dancer |

Tulkas | Sister of Oromë. Noted for her agility and speed, she is able to outrun the deer who follow her in the wild. Known for her love of dancing and celebration on the ever-green lawns of Valinor. |

Ex-Valar

[edit]| Name(s) | Duties | Spouse | Dwelling-place | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melkor or Morgoth | —— | —— | Fortress of Angband under Thangorodrim mountains, Beleriand. | Melkor means "He who arises in might". Morgoth means "Dark Enemy". Originally one of the most powerful Valar. The great enemy, the first Dark Lord; seeking to destroy both Elves and Men. Corrupts many Maiar such as Sauron and the Balrogs. |

Language

[edit]External history

[edit]Tolkien at first decided that Valarin, the tongue of the Valar as it is called in the Elvish language Quenya, would be the proto-language of the Elves, the tongue Oromë taught to the speechless Elves. He then developed the Valarin tongue and its grammar in the early 1930s.[T 17] In the 1940s, he decided to drop that idea, and the tongue he had developed became Primitive Quendian instead.[T 18] He then conceived an entirely new tongue for the Valar, still called Valarin in Quenya.[T 19]

Internal story

[edit]The Valar as spiritual immortal beings have the ability to communicate through thought and have no need for a spoken language, but it appears that Valarin develops because of their assumption of physical, humanlike (or elf-like) forms. Valarin is unrelated to the other languages constructed by J. R. R. Tolkien. Only a few words (mainly proper names) of Valarin are recorded by the Elves.[1]

Valarin is alien to the ears of the Elves sometimes to the point of genuine displeasure,[T 20] and few of them ever learn the language, only adopting some Valarin words into their own language, Quenya. The Valar know Quenya and use it to converse with the Elves, or with each other if Elves are present. Valarin contains sounds that the Elves find difficult to produce, and the words are mostly long;[T 20] for example, the Valarin word for Telperion, one of the Two Trees of Valinor, Ibrîniðilpathânezel, has eight syllables. The Vanyar adopt more words into their Vanyarin Tarquesta dialect from Valarin than the Noldor, as they lived closer to the Valar. Some of the Elven names of the Valar, such as Manwë, Ulmo, and Oromë, are adapted loanwords of their Valarin names.[1]

According to the earlier conception set forth in Tolkien's sociolinguistic text, Lhammas, the Valarin language family is subdivided into Oromëan, the Dwarves' Khuzdul (Aulëan), and Melkor's Black Speech. In this work, all Elvish languages are descended from the tongue of Oromë, while the Dwarves speak the tongue devised by Aulë, and the Black Speech of the Orcs is invented for them by Melkor.[T 21]

Analysis

[edit]Beowulf

[edit]The passage at the start of the Old English poem Beowulf about Scyld Scefing contains a cryptic mention of þā ("those") who have sent Scyld as a baby in a boat, presumably from across the sea, and to whom Scyld's body is returned in a ship funeral, the vessel sailing by itself. Shippey suggests that Tolkien may have seen in this both an implication of a Valar-like group who behave much like gods, and a glimmer of his Old Straight Road, the way across the sea to Valinor forever closed to mortal Men by the remaking of the world after Númenor's attack on Valinor.[2]

Norse Æsir

[edit]

Scholars such as John Garth have noted that the Valar resemble the Æsir, the Norse gods of Asgard.[3] Thor, for example, physically the strongest of the gods, can be seen both in Oromë, who fights the monsters of Melkor, and in Tulkas, the strongest of the Valar. Manwë, the head of the Valar, has some similarities to Odin, the "Allfather",[4] while the wizard Gandalf, one of the Maiar, resembles Odin the wanderer.[5]

Godlike power

[edit]Tolkien compared King Théoden of Rohan, charging into the enemy at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, to a Vala of great power, and to "a god of old":[T 22]

Théoden could not be overtaken. Fey he seemed, or the battle-fury of his fathers ran like new fire in his veins, and he was borne up on Snowmane like a god of old, even as Oromë the Great in the battle of the Valar when the world was young. His golden shield was uncovered, and lo! it shone like an image of the Sun, and the grass flamed into green about the white feet of his steed. For morning came ... and the hosts of Mordor wailed ... and the hoofs of wrath rode over them.[T 22]

The Episcopal priest and author Fleming Rutledge comments that while Tolkien is not equating the events here with the Messiah's return, he was happy when readers picked up biblical echoes. In her view the language here is clearly biblical, evoking Malachi's messianic prophecy "See, the day is coming, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble ... And you shall tread down the wicked, for they will be ashes under the soles of your feet".[6]

Pagan gods or angels

[edit]

The theologian Ralph C. Wood describes the Valar and Maiar as being what Christians "would call angels", intermediaries between the creator, Eru Ilúvatar, and the created cosmos. Like angels, they have free will and can therefore rebel against him.[7]

Matthew Dickerson, writing in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, calls the Valar the "Powers of Middle-earth", noting that they are not incarnated and quoting the Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger's description of their original role as "to shape and light the world".[8] Dickerson writes that while Tolkien presents the Valar like pagan gods, he imagined them more like angels and notes that scholars have compared the devotion of Tolkien's Elves to Elbereth, an epithet of Varda, as resembling the Roman Catholic veneration of Mary the mother of Jesus. Dickerson states that the key point is that the Valar were "not to be worshipped".[8] He argues that as a result, the Valar's knowledge and power had to be limited, and they could make mistakes and moral errors. Their bringing of the Elves to Valinor meant that the Elves were "gathered at their knee", a moral error as it suggested something close to worship.[8]

The scholar of literature Marjorie Burns notes that Tolkien wrote that to be acceptable to modern readers, mythology had to be brought up to "our grade of assessment". In her view, between his early work, The Book of Lost Tales,[c] and the published Silmarillion, the Valar had greatly changed, "civilized and modernized", and this had made the Valar "slowly and slightly" more Christian. For example, the Valar now had "spouses" rather than "wives", and their unions were spiritual, not physical. All the same, she writes, readers still perceive the Valar "as a pantheon", serving as gods.[9]

-

Tolkien's Valar behave as a group, so that readers perceive them as a pantheon like the Olympian gods of the Greeks.[9]

Elizabeth Whittingham comments that the Valar are unique to Tolkien, "somewhere between gods and angels". In her view they mostly lack the rough brutality of the Norse gods; they have the angels' "sense of moral rightness" but disagree with each other; and their statements most closely resemble those of Homer's Greek gods, who can express their frustration with mortal men, as Zeus does in the Odyssey[10] In a letter to Milton Waldman, Tolkien states directly that the Valar are "'divine', that is, were originally 'outside' and existed 'before' the making of the world. Their power and wisdom is derived from their Knowledge of the cosmogonical drama".[T 24] He explains that he intends them to be "of the same order of beauty, power, and majesty as the 'gods' of higher mythology".[T 24] Whittingham notes further that Tolkien likens lesser spirits, wizards, who are Maiar not Valar, to guardian angels; and that when describing the Maiar he "vacillates between 'gods' and 'angels' because both terms are close but neither is exactly right".[10] Tolkien states in another letter that the Valar "entered the world after its making, and that the name is properly applied only to the great among them, who take the imaginative but not the theological place of 'gods'."[T 25] Whittingham comments that the "thoughtful and carefully developed explanations" that Tolkien gives in these letters are markedly unlike his depictions of the Valar in his "earliest stories".[10]

Luck or providence

[edit]The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey discusses the connection between the Valar and "luck" on Middle-earth, writing that as in real life, "People ... do in sober reality recognise a strongly patterning force in the world around them" but that while this may be due to "Providence or the Valar", the force "does not affect free will and cannot be distinguished from the ordinary operations of nature" nor reduce the necessity of "heroic endeavour".[11] He states that this exactly matches the Old English view of luck and personal courage, as Beowulf's "wyrd often spares the man who isn't doomed, as long as his courage holds."[11] The scholar of humanities Paul H. Kocher similarly discusses the role of providence, in the form of the intentions of the Valar or of the creator, in Bilbo's finding of the One Ring and Frodo's bearing of it; as Gandalf says, they were "meant" to have it, though it remained their choice to co-operate with this purpose.[12]

Rutledge writes that in The Lord of the Rings, and especially at moments like Gandalf's explanation to Frodo in "The Shadow of the Past", there are clear hints of a higher power at work in events in Middle-earth:[13]

There was more than one power at work, Frodo. The Ring was trying to get back to its master ... Behind that there was something else at work, beyond any design of the Ring-maker. I can put it no plainer than by saying that Bilbo was meant to find the Ring, and not by its maker. In which case you also were meant to have it. [Tolkien's italics][T 26]

Rutledge notes that in this way, Tolkien repeatedly hints at a higher power "that controls even the Ring itself, even the maker of the Ring himself [her italics]", and asks who or what that power might be. Her reply is that at the surface level, it means the Valar, "a race of created beings (analogous to the late-biblical angels)"; at a deeper level, it means "the One", Eru Ilúvatar, or in Christian terms, divine Providence.[13]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In The Return of the King, Théoden is compared to Oromë when he leads the charge of Rohirrim in The Battle of the Pelennor Fields: "Fey he seemed, or the battle-fury of his fathers ran like new fire in his veins, and he was borne up on Snowmane like a god of old, even as Oromë the Great in the battle of the Valar when the world was young."[T 11]

- ^ "Tears unnumbered ye shall shed; and the Valar will fence Valinor against you, and shut you out, so that not even the echo of your lamentation shall pass over the mountains. On the House of Fëanor the wrath of the Valar lieth from the West unto the uttermost East, and upon all that will follow them it shall be laid also. Their Oath shall drive them, and yet betray them, and ever snatch away the very treasures that they have sworn to pursue. To evil end shall all things turn that they begin well; and by treason of kin unto kin, and the fear of treason, shall this come to pass. The Dispossessed shall they be for ever." The Silmarillion[T 12]

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales had two additional Valar, Makar and Meássë, omitted from Tolkien's later works, with roles similar to war gods of classical myth.[T 23]

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Carpenter 2023, #154 to Naomi Mitchison, September 1954

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1977, "Ainulindalë"

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1977, ch. 1, "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 23, "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 24, "Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, "Akallabêth"

- ^ Tolkien 1980, "The Istari"

- ^ a b c d e f g Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 6 "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- ^ Tolkien 1977 ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 3 "Three is Company"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 1 "Many Meetings"

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 4, ch. 10 "The Choices of Master Samwise"

- ^ Parma Eldalamberon #17, 2007, p. 150.

- ^ Tolkien 1987, ch. 7 The Lhammas

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R., "Tengwesta Qenderinwa", Parma Eldalamberon 18, p. 72

- ^ Tolkien 1994, pp. 397–407

- ^ a b Tolkien 1994 p. 398

- ^ Tolkien 1987 ch. 7 "The Lhammas"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 5, "The Ride of the Rohirrim"

- ^ Tolkien 1984, chs 3 "The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor", 4 "The Chaining of Melko", 5 "The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr", and 6 "The Theft of Melko and the Darkening of Valinor"

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #212, unsent draft continuation to Rhona Beare, on or after 14 October 1858

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 2 "The Shadow of the Past"

Secondary

[edit]- ^ a b Fauskanger, Helge Kåre. "Valarin - like the glitter of swords". Ardalambion: Of the Tongues of Arda, the invented world of J.R.R. Tolkien. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Shippey 2022, pp. 166–180.

- ^ a b Garth, John (2003). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. Houghton Mifflin. p. 86. ISBN 0-618-33129-8.

- ^ a b Chance, Jane (2004). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 169. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1.

- ^ Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1997). An investigation of the Teutonic god Óðinn; and a study of his relationship to J. R. R. Tolkien's character, Gandalf (Thesis). University of New England.

- ^ Rutledge, Fleming (2004). The Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien's Divine Design in The Lord of the Rings. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 286–288, "The Image of the Sun-King". ISBN 978-0-80282-497-4. She cites Malachi Malachi 4:1–3

- ^ a b Wood, Ralph C. (2003). The Gospel According to Tolkien. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-664-23466-9.

- ^ a b c d Dickerson, Matthew (2013) [2007]. "Valar". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 689–690. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ a b Burns, Marjorie (2004). "Norse and Christian Gods: The Integrative Theology of J. R. R. Tolkien". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 163–178. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1.

- ^ a b c Whittingham, Elizabeth A. (2008). The Evolution of Tolkien's Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth. McFarland. pp. 38, 69–70. ISBN 978-1-4766-1174-7.

- ^ a b Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 173–174, 262. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. p. 37. ISBN 0140038779.

- ^ a b Rutledge, Fleming (2004). The Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien's Divine Design in The Lord of the Rings. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 62–63, "The Third Power Makes Itself Known", and throughout. ISBN 978-0-80282-497-4.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Shippey, Tom (2022). "'King Sheave' and 'The Lost Road'". In Ovenden, Richard; McIlwaine, Catherine (eds.). The Great Tales Never End: Essays in Memory of Christopher Tolkien. Bodleian Library Publishing. pp. 166–180. ISBN 978-1-8512-4565-9.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35439-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

![Tolkien's Valar behave as a group, so that readers perceive them as a pantheon like the Olympian gods of the Greeks.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Raffaello%2C_concilio_degli_dei_02.jpg/707px-Raffaello%2C_concilio_degli_dei_02.jpg)