Dany Chamoun

Dany Chamoun | |

|---|---|

داني شمعون | |

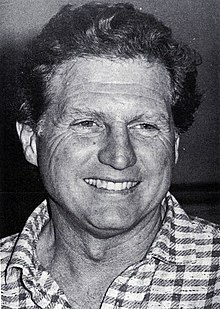

Dany Chamoun in 1988 | |

| President of the National Liberal Party | |

| In office 1985–1990 | |

| Preceded by | Camille Chamoun |

| Succeeded by | Dory Chamoun |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 August 1934 Deir el Qamar, Lebanon |

| Died | 21 October 1990 (aged 56) Beirut, Lebanon |

| Manner of death | Assassination by firearm |

| Political party | National Liberal Party |

| Children | 4 (2 surviving, including Tracy Chamoun) |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Dory Chamoun (brother) |

Dany Chamoun (Arabic: داني شمعون; 26 August 1934 – 21 October 1990) was a prominent Lebanese politician. A Maronite Christian, the younger son of former President Camille Chamoun and brother of Dory Chamoun, Chamoun was also a politician in his own right. He was murdered on October 21, 1990 at age 56, along with his family.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Chamoun was born in Deir el-Qamar on 26 August 1934.[1] He was the younger son of the former President Camille Chamoun. He studied civil engineering in the United Kingdom at Loughborough University[2]

Political career

[edit]Chamoun reported that he had not had any interest in politics before the Lebanon civil war.[2] He became the National Liberal Party Secretary of Defense in January 1976, after the death of its predecessor Naim Berdkan. As Supreme Commander of the NLP's military wing, the Tigers, he also played a major role in the early years of the Lebanese Civil War.[3]

By 1980, the Phalangist-dominated Lebanese Forces were under the command of Bachir Gemayel. The Tigers were eliminated as a military force in a surprise attack by Gemayel’s militia on 7 July 1980.

Chamoun's life was spared, and he fled to the Sunni Muslim-dominated West Beirut. He then went into self-imposed exile.[4]

He served as General Secretary of the National Liberal Party from 1983 to 1985, when he replaced his father as the party leader.[5] In 1988, he became President of the revived Lebanese Front—a coalition of nationalist and mainly Christian parties and politicians that his father had helped to found. The same year, he announced his candidacy for the Presidency of Lebanon to succeed Amine Gemayel (Bashir's brother), but Syria (which by this time occupied some 70 percent of Lebanese territory) vetoed his candidacy.

Gemayel's term expired on 23 September 1988 without the election of a successor. Chamoun declared his strong support for Michel Aoun, who had been appointed by the outgoing president to lead an interim administration and went on to lead one of two rival governments that contended for power over the next two years. He strongly opposed the Taif Agreement, which not only gave a greater share of power to the Muslim community than they had enjoyed previously, but more seriously, in Chamoun's opinion, formalized what he saw as the master-servant relationship between Syria and Lebanon, and refused to recognize the new government of the President Elias Hrawi, who was elected under the Taif Agreement.

War period

[edit]On January 18, 1976 Dany Chamoun was one of the militia commanders that participated in the Karantina Massacre, Chamoun conducted an interview after the massacre in which he denied that it was a massacre, instead referring to it as a "concise military operation" aimed at reclaiming private property.[6][7][8]

On June 28, 1976 Dany Chamoun led the attack on Tal el-Zaatar palestinian camp which resulted in a significant loss of life and displacement of Palestinian refugees. Dany Chamoun and Bachir Gemayel claimed that they didn't destroy the entire camp out of concern for the lives of civilians.[9]

Death

[edit]On 21 October 1990, Chamoun, along with his second wife Ingrid Abdelnour (aged 45), and their two sons, Tarek (aged 7) and Julian (aged 5), were all shot dead in their apartment.[10]

Chamoun was survived by his two daughters Tracy (through his first wife) and Tamara, eleven months old at the time of the massacre. Tracy had been overseas at the time of the massacre while Tamara survived.[3][11]

Aftermath and trials

[edit]On 24 June 1995, the Lebanese Tribunal found Christian rival Samir Geagea guilty of the murder of Dany Chamoun and his family.[10] He was sentenced to death commuted to life in prison with hard labour. Co-defendants Camille Karam and Rafic Saadeh were sentenced to ten and one year respectively. Ten other members of the Lebanese Forces were sentenced to life in absentia. The case was based entirely on circumstantial evidence and the trial was described by Amnesty International as seriously flawed. Geagea remained on trial for the Saydet al-Najat Church bombing.[12] The verdict was rejected by a part of the Lebanese public opinion and by Dany's brother, Dory Chamoun, who declared that the Syrian occupation army was responsible for the massacre.[10] Geagea was released as a part of a joint goodwill national reconciliation policy, after the Syrian departure.[13][14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Dany Chamoun". Wars of Lebanon. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ a b Tatro, Earleen F. (10 February 1983). "Lebanon: Dynasties dominate life..." The Lewiston Journal. Beirut. Associated Press. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ a b Jaber, Ali (22 October 1990). "Leader of a Major Christian Clan in Beirut Is Assassinated with His Family". The New York Times. p. 3.

- ^ "Lebanon's Christians". The Montreal Gazette. 22 September 1982. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "Syria has Waite, says Christian leader". The Glasgow Herald. 3 April 1987. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Lebanon Civil War 1976". YouTube.

- ^ "Karantina: City of Outsiders". 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Remembering Karantina... who does?". 20 January 2016.

- ^ "battle-of-tel-zaatar".

- ^ a b c "Lebanese Ex-Warlord Sentenced in Rival's Slaying : Mideast: Christian is the first militia chief convicted of civil war crimes. Many received amnesty. Eleven associates are also sentenced.", Los Angeles Times, 25 June 1995. Retrieved on 22 October 2016.

- ^ Chehayeb, Kareem (29 August 2022). "Lebanon presidential candidate backs anti-Hezbollah platform". Associated Press.

- ^ Middle East International No 504, 7 July 1995; Publishers Lord Mayhew, Dennis Walters MP; Giles Trendle p.13

- ^ Fisk, Robert. "Warlord gets life, but plan his vacation", Independent,, 25 June 1995.

- ^ Kennan, Rodeina. "Lebanon Militia Leader's Sentence For Murders Fans Religious Tension ", [1], 25 June 1995.

"Lebanon Historical Conflict Mapping and Analysis". Civil Society Knowledge Centre. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

External links

[edit]Jean-Marc Aractingi, La politique à mes trousses, éditions L'Harmattan, Paris, 2006 (ISBN 978-2-296-00469-6).

Media related to Dany Chamoun at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dany Chamoun at Wikimedia Commons

- 1934 births

- 1990 deaths

- People from Chouf District

- Lebanese Maronites

- Assassinated Lebanese politicians

- 20th-century Lebanese politicians

- Deaths by firearm in Lebanon

- People murdered in Lebanon

- National Liberal Party (Lebanon) politicians

- Terrorism deaths in Lebanon

- People of the Lebanese Civil War

- Children of presidents of Lebanon

- Chamoun family

- Candidates for President of Lebanon

- Lebanese anti-communists

- Lebanese warlords

- Asian politicians assassinated in the 1990s

- Politicians assassinated in 1990