Crown Dependencies

|

Flags of the Crown Dependencies | |

| Anthem: "God Save the King" | |

| Largest territory | Isle of Man |

| Official languages | English |

| Government | |

| Charles III | |

| Area | |

• Total | 768 km2 (297 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2021 Census estimate | 252,719 (exc. Sark) |

| Currency | Pound sterling[b] (£) (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC+00:00 (GMT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (BST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44 |

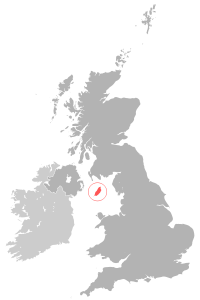

The Crown Dependencies[c] are three offshore island territories in the British Islands that are self-governing possessions of the British Crown: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey, both located in the English Channel and together known as the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Ireland.

They are not parts of the United Kingdom (UK) nor are they British Overseas Territories.[1][2] They have the status of "territories for which the United Kingdom is responsible", rather than sovereign states.[3] As a result, they are not member states of the Commonwealth of Nations.[4] However, they do have relationships with the Commonwealth and other international organizations, and are members of the British–Irish Council. They have their own teams in the Commonwealth Games.

Each island's political development has been largely independent from, though often parallel with, that of the UK,[5] and they are akin to "miniature states with wide powers of self-government".[6]

As the Crown Dependencies are not sovereign states, the power to pass legislation affecting the islands ultimately rests with the King-in-Council (though this power is rarely exercised without the consent of the dependencies, and the right to do so is disputed). However, they each have their own legislative assembly, with power to legislate on many local matters with the assent of the Crown (Privy Council, or, in the case of the Isle of Man, in certain circumstances the lieutenant-governor or, in the case of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, the Lieutenant-Governor).[7] In Jersey and the Isle of Man, the head of government is called the chief minister. In Guernsey, the head representative of the committee-based government is the President of the Policy and Resources Committee.

Terminology

[edit]The term 'Crown Dependencies' has been disputed by Gavin St Pier, former Chief Minister of Guernsey. He argues that the term was an administrative invention of Whitehall, which incorrectly implies that the islands are dependent upon the Crown, and advocates instead the use of the term 'Crown Dominion'.[8]

List of Crown Dependencies

[edit]| Name | Location | Title of monarch | Area | Population | Island | Arms | Capital | Airport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bailiwick of Guernsey |

English Channel | King in right of the Bailiwick[9][d] | 78 km2 (30 sq mi) | 67,334[12] | Alderney |

|

Saint Anne | Alderney Airport |

Guernsey |

|

Saint Peter Port[e] | Guernsey Airport | |||||

Herm |

|

(none) | (none) | |||||

Sark |

|

La Seigneurie (de facto; Sark does not have a capital city) |

(none) | |||||

| Bailiwick of Jersey |

English Channel | King in right of Jersey[13][f][d] | 118.2 km2 (46 sq mi) | 107,800[15] | Jersey |

|

Saint Helier | Jersey Airport |

| Isle of Man | Irish Sea | Lord of Mann | 572 km2 (221 sq mi) | 83,314[16] | Isle of Man |

Douglas | Isle of Man Airport (Ronaldsway Airport) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

Channel Islands

[edit]

Since 1290,[17] the Channel Islands have been governed as:

- the Bailiwick of Guernsey, comprising the islands of Alderney, Brecqhou, Guernsey, Herm, Jethou, Lihou, and Sark;

- the Bailiwick of Jersey, comprising the island of Jersey and uninhabited islets such as the Écréhous and Minquiers.

Each Bailiwick is a Crown dependency and each is headed by a Bailiff, with a Lieutenant Governor representing the Crown in each Bailiwick. Each Bailiwick has its own legal and healthcare systems and its own separate immigration policy, with "local status" in one Bailiwick having no validity in the other. The two Bailiwicks exercise bilateral double taxation treaties. Since 1961, the Bailiwicks have had separate courts of appeal, but generally, the Bailiff of each Bailiwick has been appointed to serve on the panel of appellate judges for the other Bailiwick.

Bailiwick of Guernsey

[edit]The Bailiwick of Guernsey comprises three separate jurisdictions:

- Alderney, including smaller surrounding uninhabited islands.

- Guernsey, which also includes the nearby islands of Herm, Jethou, Lihou, and other smaller uninhabited islands.

- Sark, which also includes the nearby island of Brecqhou, and other smaller uninhabited islands.

The parliament of Guernsey is the States of Deliberation, the parliament of Sark is called the Chief Pleas, and the parliament of Alderney is called the States of Alderney. The three parliaments together can also approve joint Bailiwick-wide legislation that applies in those parts of the Bailiwick whose parliaments approve it. There are no political parties in any of the parliaments; candidates stand for election as independents.[18]

Bailiwick of Jersey

[edit]

The Bailiwick of Jersey consists of the island of Jersey and a number of surrounding uninhabited islands.

The parliament is the States Assembly, the first known mention of which is in a document of 1497.[19] The States of Jersey Law 2005 introduced the post of Chief Minister of Jersey, abolished the Bailiff's power of dissent to a resolution of the States and the Lieutenant Governor's power of veto over a resolution of the States, and established that any Order in Council or Act of the United Kingdom proposed to apply to Jersey must be referred to the States so that the States can express their views on it.[20] There are few political parties, as candidates generally stand for election as independents.

Isle of Man

[edit]

The Isle of Man's Tynwald claims to be the world's oldest parliament in continuous existence, dating back to 979. (However, it does not claim to be the oldest parliament, as Iceland's Althing dates back to 930.) It consists of a popularly elected House of Keys and an indirectly elected Legislative Council. These two branches may sit separately or jointly to consider pieces of legislation, which, when passed into law, are known as "Acts of Tynwald". Candidates mostly stand for election to the Keys as independents, rather than being selected by political parties. There is a Council of Ministers headed by a chief minister.[21]

Unlike the other Crown Dependencies, the Isle of Man has a Common Purse Agreement with the United Kingdom.

City status

[edit]As overseas territories were added to the land conquered by the British, a number of towns and villages began to request formal recognition to validate their importance, and would be accorded a status if deemed to be deserving such as a borough or as a more prestigious city by the monarch. Many cities were designated over several centuries, and as Anglican dioceses began to be created the process of city creation became aligned to that used in England, being linked to the presence of a cathedral.[22]

Despite this, St Patrick's Isle adjoining the Isle of Man, which had a medieval cathedral, was never granted privileges of a city. What is now Peel Cathedral was later built nearby, but only raised to the status of a cathedral in the 1980s.

The Channel Islands were at first part of a mainland French diocese, and then came under the Bishop of Winchester after the English Reformation. These islands had no cathedral.

Since the year 2000, the UK government has arranged competitions to grant city status to settlements. In 2021, submissions for city status were invited to mark the Platinum Jubilee of Elizabeth II, with Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories being allowed to take part for the first time.[23] In the Dependencies, the only applicants were Douglas and Peel, both on the Isle of Man,[24] and Douglas was granted the honour, making it the first formal city.[25]

Constitutional status

[edit]According to the 1973 Kilbrandon Report, the Crown Dependencies are "like miniature states".[26][27] According to a 2010 Commons Justice Committee, they are independent from the UK and from each other and their relationship is with the Crown. The UK's responsibilities derive from that fact.[26]

All "insular" legislation has to receive the approval of the "King in Council", in effect, the Privy Council in London.[28] Certain types of domestic legislation in the Isle of Man and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, however, may be signed into law by the Lieutenant Governor, using delegated powers, without having to pass through the Privy Council. In Jersey, provisional legislation of an administrative nature may be adopted by means of triennial regulations (renewable after three years), without requiring the assent of the Privy Council.[29] Much legislation, in practice, is effected by means of secondary legislation under the authority of prior laws or Orders in Council.

A unique constitutional position has arisen in the Channel Islands as successive monarchs have confirmed the liberties and privileges of the Bailiwicks, often referring to the so-called Constitutions of King John, a legendary document supposed to have been granted by King John in the aftermath of 1204. Governments of the Bailiwicks have generally tried to avoid testing the limits of the unwritten constitution by avoiding conflict with British governments. Following the restoration of King Charles II, who had spent part of his exile in Jersey, the Channel Islands were given the right to set their own customs duties, referred to by the Jersey Legal French term as impôts.

The Crown

[edit]The monarch is represented by a Lieutenant Governor in each Crown dependency, but this post is largely ceremonial. Since 2010 the Lieutenant Governors of each Crown dependency have been recommended to the Crown by a panel in each respective Crown dependency; this replaced the previous system of the appointments being made by the Crown on the recommendation of UK ministers.[30][31] In 2005, it was decided in the Isle of Man to replace the Lieutenant Governor with a Crown Commissioner, but this decision was reversed before it was implemented.

The Crown in the Isle of Man

[edit]

"The Crown" is defined differently in each Crown Dependency. Legislation of the Isle of Man defines the "Crown in right of the Isle of Man" as being separate from the "Crown in right of the United Kingdom".[32] In the Isle of Man the British monarch is styled Lord of Mann, a title variously held by Norse, Scottish and English kings and nobles (the English nobles in fealty to the English Crown) until it was revested into the British monarchy in 1765. The title "Lord" is today used irrespective of the gender of the person who holds it.

The Crown in the Channel Islands

[edit]

The Channel Islands are part of the territory annexed by the Duchy of Normandy in 933 from the Duchy of Brittany. This territory was added to the grant of land given in settlement by the King of France in 911 to the Viking raiders who had sailed up the Seine almost to the walls of Paris. William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, claimed the title King of England in 1066, following the death of Edward the Confessor, and secured the claim through the Norman conquest of England. Subsequent marriages between Kings of England and French nobles meant that Kings of England had title to more French lands than the King of France. When the King of France asserted his feudal right of patronage, the then-King of England, King John, fearing he would be imprisoned should he attend, failed to fulfill his obligation.

In 1204, the title and lands of the Duchy of Normandy and his other French possessions were stripped from King John of England by the King of France. The Channel Islands remained in the possession of the King of England, who ruled them as Duke of Normandy until the Treaty of Paris in 1259. John's son, Henry III, renounced the title of Duke of Normandy by that treaty, and none of his successors ever revived it. The Channel Islands continued to be governed by the Kings of England as French fiefs, distinct from Normandy, until the Hundred Years' War, during which they were definitively separated from France. At no time did the Channel Islands form part of the Kingdom of England, and they remained legally separate, though under the same monarch, through the subsequent unions of England with Wales (1536), Scotland (1707) and Ireland (1801).

Charles III reigns over the Channel Islands directly, and not by virtue of his role as monarch of the United Kingdom. No specific title is associated with his role as monarch of the Channel Islands. The monarch has been described, in Jersey, as the "King in right of Jersey",[13] and in legislation as the "Sovereign of the Bailiwick of Jersey" and "Sovereign in right of the Bailiwick of Jersey".[14]

In Jersey, statements in the 21st century of the constitutional position by the Law Officers of the Crown define it as the "Crown in right of Jersey",[33] with all Crown land in the Bailiwick of Jersey belonging to the Crown in right of Jersey and not to the Crown Estate of the United Kingdom.[34] In Guernsey, legislation refers to the "Crown in right of the Bailiwick",[9] and the Law Officers of the Crown of Guernsey submitted that "The Crown in this context ordinarily means the Crown in right of the république of the Bailiwick of Guernsey"[35] and that this comprises "the collective governmental and civic institutions, established by and under the authority of the Monarch, for the governance of these Islands, including the States of Guernsey and legislatures in the other Islands, the Royal Court and other courts, the Lieutenant Governor, Parish authorities, and the Crown acting in and through the Privy Council."[36] This constitutional concept is also worded as the "Crown in right of the Bailiwick of Guernsey".[35]

Distinction from Overseas Territories

[edit]Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories (BOTs) share a similar geopolitical status. They are both categories of self-governing territories which fall under British sovereignty (the Head of State being the King of the United Kingdom) and for which the UK is responsible internationally. Neither Crown Dependencies nor BOTs are part of the UK and neither send representatives to the UK Parliament.[37]

However, Crown Dependencies are distinct from BOTs. Unlike BOTs, which are remnants of the British Empire, the Crown Dependencies have a much older relationship with the UK, springing from their status as "feudatory kingdoms" subject to the English Crown. The self-governing status of the BOTs evolved through Acts of Parliament and the creation of fairly homogeneous political structures. On the other hand, the political systems of the Crown Dependencies evolved in an ad hoc manner, resulting in particular and unique political structures in each dependency.[37]

Relationship with the UK

[edit]

The United Kingdom, Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories collectively form "one, undivided realm" under the British monarchy.[38][39] Crown Dependencies have the international status of "territories for which the United Kingdom is responsible" rather than sovereign states.[3] The relationship between the governments of the Crown Dependencies and the UK is "one of mutual respect and support, i.e. a partnership".[40] There is a significant gap between the official and operational relationship between the UK and the islands.[41]

Until 2001, responsibility for the UK Government's relationships with the Crown dependencies rested with the Home Office, but it was then transferred first to the Lord Chancellor's Department, then to the Department for Constitutional Affairs, and finally to the Ministry of Justice. In 2010, the Ministry of Justice stated that relationships with the Crown Dependencies are the responsibility of the United Kingdom Government as a whole, with the Ministry of Justice holding responsibility for the constitutional relationship and other ministries engaging with their opposite numbers in the Crown Dependencies according to their respective policy areas.[4]

The UK Government is solely responsible for defence and international representation[2] (although, in accordance with 2007 framework agreements,[42] the UK has elected not to act internationally on behalf of the Crown Dependencies without prior consultation). The Crown Dependencies are within the Common Travel Area and apply the same visa policy as the UK, but each Crown dependency has responsibility for its own customs and immigration services.

As in England, but not the United Kingdom as a whole, the Church of England is the established Church in the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey.[43][44]

The constitutional and cultural proximity of the islands to the UK means that there are shared institutions and organisations. The BBC, for example, has local radio stations in the Channel Islands, and also a website run by a team based in the Isle of Man (which is included in BBC North West). Similarly, ITV Channel Television is a franchise in the UK's ITV network, while the Isle of Man falls within the ITV Granada franchise area. While the islands now assume responsibility for their own post and telecommunications, they continue to participate in the UK telephone numbering plan, and they have adopted postcode systems that are compatible with that of the UK.

The growth of offshore finance in all three territories led to a "conflictual relationship" with the UK governments of the 2000s.[41]

The Crown Dependencies, together with the United Kingdom, are collectively known as the British Islands. Since the British Nationality Act 1981 came into effect, they have been treated as part of the United Kingdom for British nationality law purposes.[45] However, each Crown dependency maintains local controls over housing and employment, with special rules applying to British citizens without specified connections to that Crown dependency (as well as to non-British citizens).

Parliament Square, at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London, features all of the British flags alined: the flags of the United Kingdom, those of its four nations,[46] the county flags of these nations,[46] the three flags of the Crown Dependencies and the sixteen heraldic shields of the British Overseas Territories.[47]

On 15 May 2023, the three coats of arms of the Crown Dependencies and the sixteen heraldic shields of the British Overseas Territories, were 'immortalised' in two new stained glass windows unveiled in the Speaker's House at the New Palace of Westminster. The Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, said: "The two windows represent part of our United Kingdom family".[48]

International representation

[edit]For the purposes of international agreements, the islands were considered part of the British metropolitan territory until a declaration was agreed in 1950 that henceforth the three territories would be considered distinct from the UK and each other.[26]: 19

In 2007–2008, each Crown Dependency and the UK signed agreements[42][49][50] that established frameworks for the development of the international identity of each Crown Dependency. Among the points clarified in the agreements were that:

- The UK has no democratic accountability in and for the Crown Dependencies, which are governed by their own democratically elected assemblies;

- The UK will not act internationally on behalf of the Crown Dependencies without prior consultation;

- Each Crown Dependency has an international identity that is different from that of the UK;

- The UK supports the principle of each Crown Dependency further developing its international identity;

- The UK recognises that the interests of each Crown Dependency may differ from those of the UK, and the UK will seek to represent any differing interests when acting in an international capacity; and

- The UK and each Crown Dependency will work together to resolve or clarify any differences that may arise between their respective interests.

While the Parliament of the United Kingdom has the power to legislate for the Crown Dependencies without prior consultation, the United Kingdom is expected to seek permission from the dependencies before doing so.[51][52]

Generally speaking, the British government will only extend international agreements to the Crown Dependencies with their permission. Under international law, the British government is responsible for ensuring the dependencies comply with any treaties that extend to them.[53]

Legislative independence

[edit]The United Kingdom Parliament has power to legislate for the Islands, but Acts of Parliament do not extend to the Islands automatically, but only by express mention or necessary implication ... 'it can be said that a constitutional convention has been established whereby Parliament does not legislate for the islands without their consent on domestic matters'.

— Baroness Hale, R (Barclay) v Secy of State for Justice [2014] 3 WLR 1142, at para 12.

Acts of the UK Parliament do not usually apply to the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, unless explicitly stated. UK legislation does not ordinarily extend to them without their consent.[4] For a UK Act to extend otherwise than by an Order in Council is now very unusual.[2] The States of Jersey Law 2005[54] and subsequently the 2019 amended version of The Reform (Guernsey) Law, 1948,[55] established that all Acts of Parliament and Orders in Council which have application to either island were to be referred to their respective States assemblies for debate before registration in their Royal Court.

When deemed advisable, Acts of Parliament may be extended to the islands by means of an Order in Council (thus giving the UK Government some responsibility for good governance in the islands). An example of this was the Television Act 1954, which was extended to the Channel Islands, so as to create a local ITV franchise, known as Channel Television. By constitutional convention this is only done at the request of the insular authorities,[56] and has become a rare option (thus giving the insular authorities themselves the responsibility for good governance in the islands); the islands usually prefer nowadays to pass their own versions of laws giving effect to international treaties.

Each dependency retains its own distinct law and legal system. The Channel Islands' law systems are founded in the traditions of Norman law. For all three states, there is a right of judicial appeal to the Crown via the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, whose judgements are binding once approved and promulgated by the King via an Order-in-Council.[41]

Westminster[vague] retains the right to legislate for the islands against their will as a last resort, but this is also rarely exercised, and may, according to legal opinion from the Attorney-General of Jersey, have fallen into desuetude – although the Department for Constitutional Affairs did not accept this argument. The Marine, &c., Broadcasting (Offences) Act 1967 was one recent piece of legislation extended to the Isle of Man against the wishes of Tynwald.[citation needed]

There are many highly authoritative assertions of Parliament's sovereignty over Jersey, such as the 1861 Civil Commissioners. According to the Kilbrandon Report, the long-standing convention against Parliament intervening in domestic matters did not limit Parliament's authority to legislate for the Crown Dependencies without consent. Baroness Hale further asserted this legal opinion in 2014 (quotation above), though she did not hear arguments from Crown Dependency governments in that case.[57]

Conversely, Jeffrey Jowell argues that Parliament's powers are "of last resort" and do not therefore constitute paramount power to intervene in the Dependencies' internal affairs. He argues that as the powers have always been used within the limits of their justification, these have become constitutional law. Henry John Stephen argued that, as the Duchy of Normandy conquered England and its territory has never been annexed into England, the level of parliamentary sovereignty exercised elsewhere in the British Empire may not apply to the Channel Islands.[57]

Royal prerogative

[edit]The UK Government has a monopoly on advising how the royal prerogative – such as giving royal assent to Channel Islands' legislation – should be exercised in the Crown Dependencies.[57] Gavin St Pier, former Chief Minister of Guernsey, has called in 2023 for the Channel Islands to reconsider their constitutional relationship with the UK, "making us less susceptible to whimsical breach of conventions should the UK continue to convulse politically". He called for the Islands to have more power of the exercise of the royal prerogative by their appointment of Privy Counsellors.[58]

International relations

[edit]Commonwealth

[edit]While their constitutional status bears some resemblance to that of the Commonwealth realms, the Crown Dependencies are not independent members of the Commonwealth of Nations. They participate in the Commonwealth of Nations by virtue of their relationship with the United Kingdom, and participate in various Commonwealth institutions in their own right. For example, all three participate in the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association and the Commonwealth Games.

All three Crown Dependencies regard the existing situation as unsatisfactory and have lobbied for change. The States of Jersey have called on the British Foreign Secretary to request that the Commonwealth Heads of Government "consider granting associate membership to Jersey and the other Crown Dependencies as well as any other territories at a similarly advanced stage of autonomy". Jersey has proposed that it be accorded "self-representation in all Commonwealth meetings; full participation in debates and procedures, with a right to speak where relevant and the opportunity to enter into discussions with those who are full members; and no right to vote in the Ministerial or Heads of Government meetings, which is reserved for full members".[59] The States of Guernsey and the Government of the Isle of Man have made calls of a similar nature for a more integrated relationship with the Commonwealth,[60] including more direct representation and enhanced participation in Commonwealth organisations and meetings, including Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings.[61] The Chief Minister of the Isle of Man has said: "A closer connection with the Commonwealth itself would be a welcome further development of the Island's international relationships"[62]

European Union

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (February 2023) |

The Crown Dependencies have never been EU member states, including during the period when the UK was. During that time, their relationship with the EU was governed by Protocol 3 of the European Communities Act 1972. The Dependencies were part of the EU customs territory[63] (though only the Isle of Man was in the VAT area)[64] and took part in the free movements of goods, but not the free movement of persons, services or capital.[63] The Common Agricultural Policy of the EU never applied to the Crown Dependencies, and their citizens never took part in elections to the European Parliament. Although they were still European citizens, British citizens who had a connection to the Crown Dependencies only were not entitled to freedom of movement rights.[65][66]

With the Brexit negotiations, the House of Lords produced a report titled "Brexit: the Crown Dependencies", which stated that the "UK Government must continue to fulfil its constitutional obligations to represent the interests of the Crown Dependencies in international relations, even where these differ from those of the UK, both during the Brexit negotiations and beyond."[67] In the "Great Repeal Bill" white paper published on 30 March 2017 the UK government stated, "The Government is committed to engaging with the Crown Dependencies, Gibraltar and the other Overseas Territories as we leave the EU."[68]: ch.5

The most contentious Brexit issue was an upset to the arrangement of fishing rights of fishermen from France, Jersey, or Guernsey who wished to fish in the territorial waters of a different jurisdiction; proof of historic fishing in the jurisdiction was required in order to obtain a fishing permit, but all communications on the matter had to be routed via national or EU officials in London, Paris, or Brussels, leading to delays. This was resolved after officials in the affected French regions were allowed to communicate directly to counterparts in Guernsey and Jersey.[69]

The UK requirement for EU citizens to present passports to enter the Common Travel Area resulted in a drop of day visitors to Jersey in particular. This issue was resolved in 2022 when Jersey (with UK approval) began to allow French nationals to enter the bailiwick on day trips using just their national ID card.[70] Guernsey followed suit.

Common Travel Area

[edit]

All three Crown Dependencies participate in an open borders area, along with the United Kingdom and Ireland. An informal memorandum of understanding exists between the member countries of the Common Travel Area (CTA) whereby the internal borders of each country are expected to have minimal controls, if any, and can normally be crossed by British and Irish citizens with minimal identity documents (with certain exceptions). Under Irish law, Manx people and Channel Islanders – who were not entitled to take advantage of the European Union's freedom of movement provisions – are exempt from immigration control and immune from deportation.[71]

In May 2019, the British and Irish governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding in an effort to secure the rights of British and Irish citizens after Brexit.[72] The document was signed in London, England before a meeting of the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference, putting the rights of both countries' citizens, that were already in place under an informal agreement, on a more secure footing.

The agreement, which is the culmination of over two years' work of both governments, means the rights of both countries' citizens are protected after Brexit whilst also ensuring that Ireland can continue to meet its obligations under European Union law. The agreement took effect on 31 January 2020 when the United Kingdom left the European Union. The maintenance of the CTA involves considerable cooperation on immigration matters between the British and Irish authorities.

Customs Union

[edit]On 26 November 2018 Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man each signed a customs agreement with the United Kingdom to collectively establish a customs union.[73]

On 31 January 2020 the UK–Crown Dependencies Customs Union was officially established.[74]

In 2020 the UK Government made the Customs (Tariff Quotas) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020. These regulations apply in modified form in the Crown Dependencies.[75]

Notes

[edit]- ^

- As the King in right of the Bailiwick in the Bailiwick of Guernsey

- As the King in right of Jersey in the Bailiwick of Jersey

- As the Lord of Mann on the Isle of Mann

- ^ Each dependency produces their own local issue coins and notes and accept all UK notes.

- ^ French: Dépendances de la Couronne; Manx: Croghaneyn-crooin; Jèrriais: Dépendances d'la Couronne

- ^ a b On the Channel Islands the monarch is informally known as the Duke of Normandy. However, the title is not used in formal government publications and does not exist as a matter of Channel Islands law.[10][11]

- ^ St Peter Port is also the de facto capital of the whole Bailiwick

- ^ Also known in legislation as the "Sovereign of the Bailiwick of Jersey" and "Sovereign in right of the Bailiwick of Jersey".[14]

See also

[edit]- United Kingdom

- British Overseas Territories

- European microstates

- Commonwealth of Nations

- British Empire

- List of the leaders of the Crown Dependencies

- Royal charters applying to the Channel Islands

- United Kingdom–Crown Dependencies Customs Union

References

[edit]- ^ "Crown Dependencies – Justice Committee". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ a b c "Background briefing on the Crown dependencies: Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Fact sheet on the UK's relationship with the Crown Dependencies" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Government Response to the Justice Select Committee's report: Crown Dependencies" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. November 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Kelleher, John D. (1991). The rural community in nineteenth century Jersey (Thesis). S.l.: typescript. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Report of the Royal Commission on the Constitution, "Kilbrandon Report". 1973. Vol 1.

- ^ "Profile of Jersey". States of Jersey. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

The legislature passes primary legislation, which requires approval by The King in Council, and enacts subordinate legislation in many areas without any requirement for Royal Sanction and under powers conferred by primary legislation.

- ^ Express, Bailiwick. "Should we be Crown Dependencies… or Crown Dominions?". Bailiwick Express. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ a b "The Unregistered Design Rights (Bailiwick of Guernsey) Ordinance". Guernsey Legal Resources. 2005. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ Matthews, Paul (1999). "Lé Rouai, Nouot' Duc" (PDF). Jersey and Guernsey Law Review. 1999 (2) – via Jersey Legal Information Board.

- ^ The Channel Islands, p. 11, at Google Books

- ^ "Guernsey - The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. 30 March 2022. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Review of the Roles of the Crown Officers" (PDF). States of Jersey. 4 May 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Succession to the Crown (Jersey) Law 2013". Jersey Legal Information Board. 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ "Jersey's population increases by 1,100 in the last year". itv.com/. 18 June 2020. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "2016 Isle of Man Census Report" (PDF). Gov.im. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Mollet, Ralph (1954). A Chronology of Jersey. Jersey: Société Jersiaise.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Guernsey". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ Balleine, G. R.; Syvret, Marguerite; Stevens, Joan (1998). Balleine's History of Jersey (Revised & Enlarged ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 1-86077-065-7.

- ^ "States of Jersey Law 2005". Jersey Legal Information Board. 5 May 2006.

- ^ "The Council of Ministers". Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Beckett, J. V. (2005). City status in the British Isles, 1830-2002. Historical urban studies. Aldershot, Hants, England ; Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5067-6.

- ^ "Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours Competition". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Full list of places aiming to become Jubilee cities revealed". GOV.UK. 4 January 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "List of cities (HTML)". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Torrance, David (5 July 2019). Briefing Paper: The Crown Dependencies (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Constitution 1969–1973 Volume 1, Cmnd 5460, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, para 1360.

- ^ "Review of the Roles of the Crown Officers" (PDF). States of Jersey. 29 March 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Southwell, Richard (October 1997). "The Sources of Jersey Law". Jersey Law Review. Retrieved 31 July 2017 – via Jersey Legal Information Board.

- ^ "£105,000 – the tax-free reward for being a royal rep". This Is Jersey. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011.

- ^ Ogier, Thom (3 July 2010). "Guernsey will choose its next Lt-Governor". This Is Guernsey. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011.

- ^ "The Air Navigation (Isle of Man) Order 2007 (No. 1115)". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Review of the Roles of the Crown Officers" (PDF). States of Jersey. 2 July 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Written Question To H.M. Attorney General by Deputy P.V.F. Le Claire of St. Helier". States of Jersey. 22 June 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Review of the Roles of the Jersey Crown officers" (PDF). States of Jersey. 30 March 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ De Woolfson, Joel (21 June 2010). "It's a power thing..." Guernsey Press. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b Mut Bosque, Maria (May 2020). "The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era". Island Studies Journal. 15 (1): 151–168. doi:10.24043/isj.114. ISSN 1715-2593. S2CID 218937362.

- ^ Bosque, Maria Mut (2022). "Questioning the current status of the British Crown Dependencies". Small States & Territories. 5 (1): 55–70. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023 – via University of Malta.

- ^ Loft, Philip (1 November 2022). The separation of powers in the UK's Overseas Territories (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Crown Dependencies – Justice Committee: Memorandum submitted by the Policy Council of the States of Guernsey". Parliament of the United Kingdom. October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Morris, Philip (1 March 2012). "Constitutional Practices and British Crown Dependencies: The Gap between Theory and Practice". Common Law World Review. 41 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1350/clwr.2012.41.1.0229. ISSN 1473-7795. S2CID 145209106.

- ^ a b "Framework for developing the international identity of Jersey" (PDF). States of Jersey. 1 May 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Gell, Sir James. "Memorandum Respecting the Ecclesiastical Courts of the Isle of Man..." Isle of Man Online. Archived from the original on 18 November 2002. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "About". Guernsey Deanery. Church of England. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "[Withdrawn] Nationality instructions: Volume 2". UK Border Agency. 10 December 2013. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Historic county flags raised in day of national celebration". Gov.uk. Gov.uk. 23 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Overseas Territories flags flown for the first time in Parliament Square". Gov UK. Gov UK. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Channel Islands represented in Speaker's House". BBC News. 15 May 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Framework for developing the international identity of Guernsey". States of Guernsey. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Framework for developing the international identity of the Isle of Man" (PDF). Isle of Man Government. 1 May 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Constitution 1969–1973, p. Paragraphs 1469–1473

- ^ "How autonomous are the Crown Dependencies?". Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ "Fact sheet on the UK's relationship with the Crown Dependencies: International Personality" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ "States of Jersey Law 2005". jerseylaw.je. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ P.2019/35 Archived 8 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine of the States of Deliberation of the Island of Guernsey to pass Project de Loi entitled The Reform (Guernsey) (Amendment) Law, 2019. Accessed 8 December 2021.

- ^ "UK Legislation and the Crown Dependencies". Department for Constitutional Affairs. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "Jersey's Relationship with the UK Parliament Revisited". Jersey Law Review. Retrieved 12 February 2023 – via Jersey Legal Information Board.

- ^ Express, Bailiwick. "Should we be Crown Dependencies... or Crown Dominions?". Bailiwick Express Jersey. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Affairs Committee: Written evidence from States of Jersey". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Foreign Affairs Committee: The role and future of the Commonwealth". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Foreign Affairs Committee: Written evidence from the States of Guernsey". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Isle of Man welcomes report on Commonwealth future". Isle of Man Government. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Article 3(1) of Council Regulation 2913/92/EEC of 12 October 1992 establishing the Community Customs Code (as amended) (OJ L 302)". EUR-Lex. 19 October 1992. pp. 1–50. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Article 6 of Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 (as amended) on the common system of value added tax (OJ L 347)". EUR-Lex. 11 December 2006. p. 1. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Section 1 of the British Nationality Act 1981 grants citizenship to (most) people born in the United Kingdom. Section 50 of the Act defines 'United Kingdom' for the purposes of that Act to include the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, overriding the usual definition from Schedule 1 of the Interpretation Act 1978 which excludes them.

- ^ Protocol 3 of the Treaty of Accession of the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark (OJ L 73, 27 March 1972).

- ^ "House of Lords European Union Committee – Brexit: the Crown Dependencies" (PDF). Parliament of the United Kingdom. 23 March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Legislating for the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union" (PDF). Department for Exiting the European Union. 30 March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Morel, Julian. "Major breakthrough in fishing dispute as Macron allows direct talks". Bailiwick Express. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Extension to ID cards scheme for French nationals travelling to Jersey". States of Jersey. 2 October 2023.

- ^ As per the provisions of the S.I. No. 97/1999 — Aliens (Exemption) Order, 1999 Archived 17 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine and Immigration Act 1999 Archived 16 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Memorandum of Understanding between the UK and Ireland on the CTA". GOV.UK. 8 May 2019. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Brexit: the impact of the end of the Transition Period on Guernsey and Jersey". Carey Olsen. 18 January 2021.

a new Customs Arrangement (the 'UK-CD Customs Union') between the UK and the Crown Dependencies, enabling the Islands to enjoy the benefit of free trade agreements entered into by the UK

- ^ Angeloni, Cristian (28 February 2020). "Crown dependencies weigh in on start of Brexit negotiations". International Adviser. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Customs (Tariff Quotas) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2020/1432