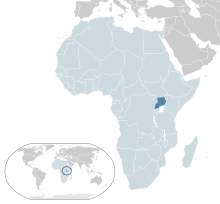

History of the Jews in Uganda

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| History of Uganda | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Special themes | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

The history of the Jews in Uganda is connected to some local tribes who have converted to Judaism, such as the Abayudaya, down to the twentieth century when Uganda under British control was offered to the Jews of the world as a "Jewish homeland" under the British Uganda Programme known as the "Uganda Plan" and culminating with the troubled relationship between Ugandan leader Idi Amin with Israel that ended with Operation Entebbe known as the "Entebbe Rescue" or "Entebbe Raid" of 1976.[1]

Abayudaya[edit]

The small Abayudaya tribe converted to Judaism in the early 20th century.[2] Their population is estimated at 2,500[3] having once been as large as 3,000 prior to the persecutions of the Idi Amin regime.[4] Like their neighbors, they are subsistence farmers. Most Abayudaya are of Bagwere origin, except for those from Namutumba who are Basoga. They speak Luganda, Lusoga or Lugwere, although some have learned Hebrew as well.[5]

British Uganda Programme[edit]

The British Uganda Programme was a plan to give a portion of British East Africa to the Jewish people as a homeland.[6] The offer was first made by British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain to Theodore Herzl's Zionist group in 1903. He offered 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of the Mau Plateau in what is today Kenya and Uganda.[7] The offer was a response to pogroms against the Jews in Russia, and it was hoped the area could be a refuge from persecution for the Jewish people.[8]

Modern relations with Israel[edit]

In 1972 relations with Israel soured. Although Israel had previously supplied Uganda with arms, in 1972 Idi Amin, enraged over Israel's refusal to supply Uganda with jets for a war with neighboring Tanzania, expelled Israeli military advisers and turned to Libya and the Soviet Union for support.[9] Amin became an outspoken critic of Israel.[1] In the documentary film General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait, he discussed his plans for war against Israel, using paratroops, bombers and suicide squadrons.[10] Amin later stated that Hitler "was right to burn six million Jews".[11]

In June 1976, Amin allowed an Air France airliner hijacked by two members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations (PFLP-EO) and two members of the German Revolutionäre Zellen to land at Entebbe Airport. There, the hijackers were joined by three more. Soon after, 156 non-Jewish hostages who did not hold Israeli passports were released and flown to safety, while 83 Jews and Israeli citizens, as well as 20 others who refused to abandon them (among whom were the captain and crew of the hijacked Air France jet), continued to be held hostage. In the subsequent Israeli rescue operation, codenamed Operation Thunderbolt (popularly known as Operation Entebbe), nearly all the hostages were freed. Three hostages died during the operation and 10 were wounded; seven hijackers, 45 Ugandan soldiers, and one Israeli soldier, Yoni Netanyahu, were killed. A fourth hostage, 75-year-old Dora Bloch, who had been taken to Mulago Hospital in Kampala prior to the rescue operation, was subsequently murdered in reprisal. The incident further soured Uganda's international relations, leading Britain to close its High Commission in Uganda.[12]

Operation Entebbe[edit]

Operation Entebbe was a hostage-rescue mission carried out by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) at Entebbe Airport in Uganda on July 4, 1976.[13] A week earlier, on June 27, an Air France plane with 248 passengers was hijacked by Palestinian terrorists and supporters and flown to Entebbe, near Kampala, the capital of Uganda. Shortly after landing, all non-Jewish passengers were released. The operation took place at night, as Israeli transport planes carried 100 elite commandos over 2,500 miles (4,000 km) to Uganda for the rescue operation. The operation, which took a week of planning, lasted 90 minutes and 103 hostages were rescued. Five Israeli commandos were wounded and one, the commander, Lt Col Yonatan Netanyahu, was killed. All the hijackers, three hostages and 45 Ugandan soldiers were killed, and 11 Soviet-built MiG-17's of Uganda's air force were destroyed.[14] A fourth hostage was murdered [15] by Ugandan army officers at a nearby hospital.[16]

Reactions[edit]

Dora Bloch, a 75-year-old British Jewish immigrant, was taken to Mulago Hospital in Kampala, and was murdered by the Ugandan government, as were some of her doctors and nurses for apparently trying to intervene.[17] In April 1987, Henry Kyemba, Uganda's Attorney General and Minister of Justice at the time, told the Uganda Human Rights Commission that Bloch had been dragged from her hospital bed and murdered by two army officers on Idi Amin's orders. Mrs Bloch had been shot and her body dumped in the trunk of a car which had Ugandan intelligence services number plates. Bloch's remains were recovered near a sugar plantation 20 miles (32 km) east of Kampala in 1979,[16] after the Ugandan–Tanzanian War led to the end of Amin's rule.[18]

The government of Uganda, led by Juma Oris, the Ugandan Foreign Minister at the time, later convened a session of the United Nations Security Council to seek official condemnation of the Israeli raid,[19] as a violation of Ugandan sovereignty. The Security Council ultimately declined to pass any resolution on the matter, condemning neither Israel, nor Uganda. In his address to the council, Israeli ambassador Chaim Herzog said:

We come with a simple message to the Council: we are proud of what we have done because we have demonstrated to the world that a small country, in Israel's circumstances, with which the members of this Council are by now all too familiar, the dignity of man, human life and human freedom constitute the highest values. We are proud not only because we have saved the lives of over a hundred innocent people—men, women and children—but because of the significance of our act for the cause of human freedom.[20][21]

— HERZOG, Chaim.

Israel received support from the Western World for its operation. West Germany called the raid "an act of self defense". Switzerland and France also praised Israel for the operation. Significant praise was received from representatives of the United Kingdom and the US both of whom called it "an impossible operation". Some in the United States noted that the hostages were freed on July 4, 1976, which was 200 years since the signing of the US declaration of independence.[22][23][24]

UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim described the raid as "a serious violation of the national sovereignty of a United Nations member state".[25] Dozens of Ugandan soldiers were killed in the raid. The Arab and Communist world condemned the operation calling it an act of aggression.

For refusing to depart (and subsequently leave some of his passengers as hostages) when given leave to do so by the hijackers, Captain Bacos was reprimanded by his superiors at Air France and suspended from duty for a period. He was awarded by Israel for his heroism in refusing to leave the Jewish hostages behind.[26]

In the ensuing years, Betser and the Netanyahu brothers—Iddo and Benjamin, all Sayeret Matkal veterans—argued in increasingly public forums about who was to blame for the unexpected early firefight which caused Yonatan Netanyahu's death and partial loss of tactical surprise.[27][28]

See also[edit]

- Early history of Uganda

- Foreign relations of Israel

- History of Uganda (1962–71)

- History of Uganda (1971–79)

- History of Uganda (1979–present)

- Uganda Protectorate

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jamison, M. Idi Amin and Uganda: An Annotated Bibliography, Greenwood Press, 1992, pp.155–6

- ^ Ornstein, Dan (2023-04-02). "For Passover, I sent matzo to the Jews of Uganda. They've given me a gift as well". Goats and Soda. NPR. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ Harrisberg, Kim (14 April 2014). "The lost Jews of Uganda". Daily Maverick. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Shadrach Levi, Mugoya (November 6, 2017). "We Are the Jews of Uganda. This Is Our Story". The Forward. Rachel Fishman Feddersen. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Parfitt, Tudor ( Black Jews in Africa and the Americas, Harvard University Press 2013

- ^ "The Uganda Proposal". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Joseph Telushkin (1991). Jewish literacy. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-688-08506-7.

Britain stepped into the picture, offering Herzl land in the largely undeveloped area of Uganda (today, it would be considered an area of Kenya). ...

- ^ Theodor Herzl's biography at Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Tall, Mamadou (Spring–Summer 1982). "Notes on the Civil and Political Strife in Uganda". Issue: A Journal of Opinion. 12 (1/2): 41–44. doi:10.2307/1166537. JSTOR 1166537.

- ^ General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait. Le Figaro Films. 1974. ISBN 0-7800-2507-5.

- ^ End for Amin the executioner The Sun-Herald August 17, 2003

- ^ "On this day: July 7th 1976: British grandmother missing in Uganda". BBC. 1976-07-07. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Smith, Terence (4 July 1976). "HOSTAGES FREED AS ISRAELIS RAID UGANDA AIRPORT; Commandos in 3 Planes Rescue 105-Casualties Unknown Israelis Raid Uganda Airport And Free Hijackers' Hostages". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ "Hostage Rescue at the Raid on Entebbe". OperationEntebbe.Com. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ Middle Eastern terrorism, Mark Ensalaco p. 101 University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Body of Amin Victim Is Flown Back to Israel". New York Times. 4 June 1979, Monday, p. A3.

- ^ Ben, Eyal (3 July 2006). "Special: Entebbe's unsung hero". YNetNews.com. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ Verkaik, Robert (13 February 2007). "Revealed: the fate of Idi Amin's hijack victim—Crime, UK—The Independent". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ Teltsch, Kathleen. "Uganda Bids U.N. Condemn Israel for Airport Raid." New York Times. 10 July 1976. (Section: The Week In Review)

- ^ Herzog, Chaim. Heroes of Israel. p. 284.

- ^ Fendel, Hillel. "Israel Commemorates 30th Anniversary of Entebbe Rescue." Israel National News.

- ^ "Age of Terror: Episode one". BBC News. 16 April 2008.

- ^ "עכשיו, במבצע". 31 March 2008.

- ^ מבצע אנטבה Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "July 4, Day of Operation Entebbe, Israel Upgrades Uganda Airport". The Jewish Press. 2013-07-04. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ Kaplan, David E. "A historic hostage-taking revisited." Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine Jerusalem Post. 3 August 2006.

- ^ Sharon Roffe-Ofir "Entebbe's open wound" Ynet, 7 February 2006

- ^ Josh Hamerman "Battling against 'the falsification of history'" Ynet News, 4 February 2007