Muscogee Nation

The Muscogee Nation

Este Mvskokvlke (Creek) | |

|---|---|

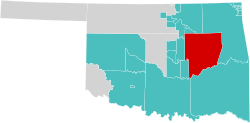

Location (red) in the U.S. state of Oklahoma | |

| Established | August 7, 1856 |

| Capital | Okmulgee |

| Government | |

| • Chief | David Hill |

| Population (2023)[1] | |

| • Total | 100,000 |

| Demonym | Muscogee |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| Website | www |

Flag | |

Seal of the Muscogee Nation | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 100,000[1] (census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Muscogee[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Muscogee people, Alabama, Hitchiti, Koasati, Natchez Nation, Shawnee, Seminole, and Yuchi |

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation,[3] is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati, with Muscogee retaining the largest number of speakers. They commonly refer to themselves as Este Mvskokvlke (pronounced [isti məskóɡəlɡi]). Historically, they were often referred to by European Americans as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast.[4]

The Muscogee Nation is the largest of the federally recognized Muscogee tribes. The Muskogean-speaking Alabama, Koasati, Hitchiti, and Natchez people are also enrolled in this nation. Algonquian-speaking Shawnee[5] and Yuchi (language isolate) are also enrolled in the Muscogee Nation, although historically, the latter two groups were from different language families and cultures than the Muscogee.

Other federally recognized Muscogee groups include the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, Kialegee Tribal Town, and Thlopthlocco Tribal Town of Oklahoma; the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians in Alabama.

Jurisdiction

[edit]

The Muscogee Nation is headquartered in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, and serves as the seat of tribal government. The Muscogee Nation's Reservation status was affirmed in 2020 by the decision of the United States Supreme Court in Sharp v. Murphy, which held that the allotted Muscogee Nation reservation in Oklahoma has not been disestablished and therefore retains jurisdiction over tribal citizens in Creek, Hughes, Okfuskee, Okmulgee, McIntosh, Muskogee, Tulsa, and Wagoner counties in Oklahoma.[6][7]

Government

[edit]

The government of the Muscogee Nation is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. Okmulgee is the capital of the Muscogee Nation and also serves as the seat of government.[8]

Executive branch

[edit]The Executive branch is led by the Principal Chief, Second Chief, Tribal Administrator, and Secretary of the Nation. The Principal Chief and Second Chief are democratically elected every four years. Citizens cast ballots for both the Principal Chief and Second Chief as they are elected individually. The Principal Chief then chooses staff; some of which must be confirmed by the legislative branch known as The National Council. The current members of the executive branch are as follows:

- David W. Hill, Principal Chief

- Del Beaver, Second Chief

Legislative branch

[edit]The legislative branch is the National Council and consists of sixteen members elected to represent the 8 districts within the tribe's jurisdictional area. National Council representatives draft and sponsor the laws and resolutions of the Nation.[8] The eight districts include: Creek, Tulsa, Wagoner, Okfuskee, Muskogee, Okmulgee, McIntosh, and Tukvpvtce (Hughes).

Judicial branch

[edit]Under the inherent sovereign authority of the Mvskoke Nation, the Nation's citizens ratified the modern Mvskoke Nation Constitution on October 6, 1979. The Supreme Court was re-established by Article VII. The Court is vested with exclusive appellate jurisdiction over all civil and criminal matters that fall under Mvskoke jurisdiction and serves as the final interpretive authority on Mvskoke law. The Court consists of seven justices who serve six-year terms after nomination by the Principal Chief and confirmation by the National Council. Annually, the Court selects from its members a Chief Justice and Vice-Chief Justice. The Justices are as follows:[9]

- Chief Justice Richard C. Lerblance

- Vice-Chief Justice Amos McNac

- Justice Andrew Adams III

- Justice Montie R. Deer

- Justice Leah Harjo-Ware

- Justice Kathleen R Supernaw

- Justice George Thompson Jr.

The Muscogee Nation also has its own Bar Association, referred to as the M(C)N Bar Association. The Board members include President Shelly Harrison, Vice President Clinton A. Wilson, and Secretary/Treasurer Greg Meier. The M(C)N Bar Association has Facebook and Twitter accounts for members to stay connected.[10]

Citizenship

[edit]In 2023, the total population of Muscogee citizens reached exactly 100,000 persons,[1] a significant increase from 2019 when the total population was 87,344, of which 65,070 resided in Oklahoma with 11,194 of that number living in the City of Tulsa.[11] The population is essentially evenly split in half by gender, with most citizens being between the ages of 18 and 54 years old.[11] The criteria for Citizenship are to be Creek by Blood and trace back to a direct ancestor listed on the 1906 Dawes Roll by issuance of birth and/or death certificates. The Citizenship Board office is governed by a Citizenship Board consisting of five members. This office provides services to citizens of the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma or to potential citizens in giving direction or assisting in the lineage verification process of the Muscogee people. The mission of this office is to verify the lineage of descendants of persons listed on the 1906 Dawes Roll. In doing so, research is involved in the whole aspect of attaining citizenship. The Director of the Citizenship Board is Nathan Wilson.[12]

A 2023 Muscogee court ruling found that descendants of black slaves held by Muscogee nation members can be granted citizenship in the nation.[13]

Services

[edit]

The Nation operates its own division of housing and issues vehicle license plates.[14] Their Division of Health contracts with Indian Health Services to maintain the Creek Nation Community Hospital and several community clinics, a vocational rehabilitation program, nutrition programs for children and the elderly, and programs dedicated to diabetes, tobacco prevention, and caregivers.[15]

The Muscogee Nation operates the Lighthorse Tribal Police Department, with 43 active employees.[16] The tribe has its own program for enforcing child support payments.

The Mvskoke Food Sovereignty Initiative is sponsored by the nation. It educates and encourages tribal members to grow their own traditional foods for health, environmental sustainability, economic development, and sharing of knowledge and community between generations.[17]

The Muscogee Nation also operates a Communications Department that produces a twice-monthly newspaper, the Mvskoke News, and a weekly television show, the Native News Today.

Economic development

[edit]The tribe operates a budget in excess of $290 million, has more than 4,000 employees, and provides services within their jurisdiction.[18]

The tribe has both gaming (casino related) and non-gaming businesses. Non-gaming business ventures include both Muscogee Nation Business Enterprise[19] (MNBE) and Onefire.[20] MNBE and Onefire oversee economic development as well as investigating, planning, organizing and operating business ventures projects for the tribe related to non-gaming business.[14] Gaming enterprises consist of 9 stand alone casinos; the largest being River Spirit Casino Resort featuring Margaritaville in Tulsa. The revenue from both gaming and non-gaming business are reinvested to develop new businesses, as well as support the welfare of the tribe.

The Muscogee Nation also operates two travel plaza truck stops.

Civic institutions

[edit]

The Creek National Capitol, also known as the Council House, was built in 1878 and is located on a landscaped city block in downtown Okmulgee. Exterior walls of the symmetrical Italianate building are constructed of rough-faced sandstone in a coarse ashlar pattern with paired brackets at the cornice. The building measures 100 by 80 feet with two identical entrances on both the north and south elevations. A bracketed porch with a balcony above covers each entrance and 6-over-6, double-hung sash windows line the exterior walls. The hipped roof is crowned with a square wooden cupola, which originally housed bells to call tribal leaders to meetings. The inside of the building is centrally divided by a stair hall, creating an east and west side. The stairs lead to a similarly divided second story. The House of Warriors had a large meeting room on the east side, while the House of Kings had a meeting room, referred to as the Supreme Court Room, on the west side. The capitol served as a meeting place for the legislative branches of the Muscogee Nation until 1907, when Oklahoma became a state. Tribal business in the capitol ended in 1908, when Congress authorized the possession of tribal lands, effectively ceasing tribal sovereignty. From the time of statehood to 1916, the Council House served as the Okmulgee County Courthouse. In 1926, Oklahoma Native Will Rogers visited Okmulgee to entertain a crowd of nearly 2,000. While doing so, he said that it was important to maintain buildings like the Creek National Capitol, since people were speculating on what they would use the Capitol for now that its legislative use had expired. His words had an impact, considering the building is still standing to this day. Since then, the building has served as a sheriff’s office, Boy Scout meeting room, and a YMCA. In 1961, the building was designated as a National Historic Landmark. By 1979, tribal sovereignty had been fully renewed and the Muscogee adopted a new constitution. The Creek Council House underwent a full restoration in 1989–1992 and reopened as a museum operated by the City of Okmulgee and the Creek Indian Memorial Association. In 2010, the Muscogee Nation purchased the building back from the City of Okmulgee for $3.2 million. It now serves as a museum of tribal history, which is open to the public and exhibits Native American History and culture.[21][22][23]

Tribal college

[edit]

In 2004, the Muscogee Nation founded a tribal college in Okmulgee, the College of the Muscogee Nation (CMN), one of only 38 Tribal Colleges in the US. CMN is a two-year institution, offering associate degrees in Tribal Services, Police Science, Gaming, and Native American Studies. It offers Mvskoke language, Native American History, Tribal Government, and Indian Land Issue classes as well. The CMN offers financial aid through FAFSA and offers on-campus housing. For the spring trimester in 2018, individual student enrollment was 197. A needs assessment survey revealed that a majority of Muscogee citizens were interested in attending the tribal college. Of 386 tribal citizens from the 8 districts, 86% of those were interested in attending college responded that they would attend a tribal college. When asked if they had others in their family who were interested in attending a tribal college 25% of the survey sample responded yes.[24]

History

[edit]The nation includes the Muscogee people and descendants of their African-descended slaves[25] who were forced by the US government to relocate from their ancestral homes in the Southeast to Indian Territory in the 1830s, during the Trail of Tears. They signed another treaty with the federal government in 1856.[26]

During the American Civil War, the tribe split into two factions, one allied with the Confederacy and the other, under Opothleyahola, allied with the Union.[27] There were conflicts between pro-Confederate and pro-Union forces in the Indian Territory during the war. The pro-Confederate forces pursued the loyalists who were leaving to take refuge in Kansas. They fought at the Battle of Round Mountain, Battle of Chusto-Talasah, and Battle of Chustenahlah, resulting in 2,000 deaths among the 9,000 loyalists who were leaving.[28]

After defeating the Confederacy, the Union required new peace treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes, which had allied with that insurrection. The Treaty of 1866 required the Creek to abolish slavery within their territory and to grant tribal citizenship to those Creek Freedmen who chose to stay in the territory; this citizenship was to include voting rights and shares of annuities and land allotments.[29] If the Creek Freedmen moved out to United States territory, they would be granted United States citizenship, as were other emancipated African Americans.[30]

The Muscogee established a new government in 1866 and selected a new capital of Okmulgee. In 1867 they ratified a new constitution to incorporate elements of the new peace treaty, and their own desire for changes.[4]

They built their capitol building in 1867 and enlarged it in 1878. Today the Creek National Capitol is a National Historic Landmark. It now houses the Creek Council House Museum, as more space was needed for the government. During the prosperous final decades of the 19th century, when the tribe had autonomy and minimal interference from the federal government, the Nation built schools, churches, and public houses.[4]

At the turn of the century, Congress passed the 1898 Curtis Act, which dismantled tribal governments in another federal government attempt to assimilate the Native American people. The related Dawes Allotment Act required the break-up of communal tribal landholdings to allot land to individual households. This was intended to encourage adoption of the European-American style of subsistence farming and property ownership. It also was a means to extinguish Native American land claims and prepare for admitting Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory as a state, which took place in 1907.

The government declared that communal land remaining after allotments to existing households was "surplus". It was classified as excess and made available for sale to non-Natives. This resulted in the Muscogee and other tribes losing control over much of their former lands.

In the hasty process of registration, the Dawes Commission registered tribal members in three categories: they distinguished among "Creek by Blood" and "Creek Freedmen," a category where they listed anyone with visible African ancestry, regardless of their proportion of Muscogee ancestry; and "Intermarried Whites." The process was so confused that some members of the same families of Freedmen were classified into different groups. The 1906 Five Civilized Tribes Act (April 26, 1906) was passed by the US Congress in anticipation of approving statehood for Oklahoma in 1907. During this time, the Muscogee had lost more than 2 million acres (8,100 km2) to non-Native settlers and the US government.

Later, when Muscogee communities organized and set up governments under the 1936 Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act, some former Muscogee tribal towns reorganized that were in former Indian Territory and the Southeast. Some descendants had remained there and preserved cultural continuity. Others reorganized and gained recognition later in the 20th century. The following Muscogee groups have gained federal recognition as tribes: the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, Kialegee Tribal Town, and Thlopthlocco Tribal Town of Oklahoma; the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, and the Poarch Band of Creeks in Alabama.

The Muscogee Nation did not reorganize its government and regain federal recognition until 1970. This was an era of increasing Native American activism across the country. In 1979 the tribe ratified a new constitution that replaced the 1866 constitution.[4] The pivotal 1976 court case Harjo v. Kleppe helped end US federal paternalism. It ushered in an era of growing self-determination. Using the Dawes Rolls as a basis for determining membership of descendants, the Nation has enrolled more than 58,000 members, descendants of the allottees.

Muscogee Freedmen controversy

[edit]From 1981 to 2001, the Muscogee had membership rules that allowed applicants to use a variety of documentary sources to establish qualifications for membership.

In 1979 the Muscogee Nation Constitutional Convention voted to limit citizenship in the Nation to persons who could prove descent by blood, meaning that members had to be able to document direct descent from an ancestor listed on the Dawes Commission roll in the category of "Creek by Blood". Persons proving they are descended from persons listed as Creek by blood can become citizens of the Muscogee Nation. The 1893 registry was established to identify citizens of the nation at the time of allotment of communal lands and dissolution of the reservation system and tribal government.[31]

The 1979 vote on citizenship excluded descendants of persons recorded only as Creek Freedmen in the Dawes Rolls. This decision has been challenged in court by those descendants, according to the 1866 treaty[32] of "Creek Freedmen."[33][34]

The Freedmen were listed on the Dawes Rolls. Some descendants can prove by documentation in other registers that they had ancestors with Muscogee blood. The Freedmen had been listed on a separate register, regardless of their proportion of Muscogee ancestry. This classification did not acknowledge the unions and intermarriage that had taken place for years between the ethnic groups. Prior to the change in code, Muscogee Freedmen could use existing registers and the preponderance of evidence to establish qualification for citizenship, and were to be aided by the Citizenship Board. The Muscogee Freedmen have challenged their exclusion from citizenship in legal actions[35][36] which are pending.[37]

Notable Muscogee Nation people

[edit]Historic Muscogee people are listed in the Muscogee article.

- Fred Beaver (1911–1980), Muscogee/Seminole painter and muralist

- R. Perry Beaver (1938-2014), principal chief, football coach

- Acee Blue Eagle (1909-1959), actor, artist, author, and educator

- Ernest Childers (1918–2005), lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army during World War II and the first Native American to be awarded a Medal of Honor during that war

- Eddie Chuculate (b. 1972), Muscogee/Cherokee journalist and fiction writer

- Helen Chupco (1919-2004), Methodist missionary and tribal councilwoman for 23 years

- Fred S. Clinton (1874-1955), surgeon

- Shelly Crow (1948–2011), first woman to serve in the executive branch of the National Council, as Second Chief

- Sarah Deer (b. 1972), lawyer, professor of law, and MacArthur Fellow

- Jennifer Foerster, poet and professor

- Thomas Gilcrease (1890–1962), oilman, founder of the Gilcrease Museum

- Chitto Harjo (1846-1911), orator, veteran, and traditionalist, leader of the Crazy Snake Rebellion

- Joy Harjo (b. 1959), poet and jazz musician, first Native American United States Poet Laureate

- Joan Hill (1930–2020), painter

- Isparhecher (1829-1902), political activist, traditionalist leader

- Jack Jacobs (1919–1974), football player

- Lauren J. King (b. 1982), attorney

- William Harjo LoneFight (b. 1966), author, President of Native American Services, languages and cultural activist

- Timothy Long, pianist and assistant conductor of the Metropolitan Opera

- Louis Oliver (1904–1991), poet

- Jim Pepper (1941–1992), Muscogee/Kaw jazz musician

- Grant-Lee Phillips (born 1963), alternative Americana singer-songwriter and founder-songwriter of Grant Lee Buffalon[38]

- Pleasant Porter (1840–1907), Principal Chief from 1899 to 1907

- Alexander Posey (1873—1908), poet, humorist, journalist, and politician

- Allie P. Reynolds (1917-1994), professional baseball player for the Cleveland Indians and New York Yankees, businessman

- Will Sampson (1933–1987), film actor, noted for performance in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975)

- Cynthia Leitich Smith (born 1967), children's book author, noted for Jingle Dancer

- Dana Tiger (b. 1961), artist

- Johnny Tiger, Jr. (1940–2015), painter and sculptor

- Tommy Warren, (1917–1968) Major League Baseball professional athlete

- France Winddance Twine (born 1960), professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara

- Micah Ian Wright (born 1969), writer, videogame designer, graphic novelist, and film director[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Stella Mason (unknown–1918), she was subject to a known lawsuit, highlighting a pattern of abuse against freedmen among the Five Civilized Tribes

- Muscogee

- Muscogee language

- Muscogee mythology

- Crazy Snake Rebellion

- Green Corn ceremony

- Ocmulgee National Monument

- Stomp dance

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Harper, Braden (September 23, 2023). "Muscogee (Creek) Nation enrolls its 100,000th citizen". Mvskoke Media. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ " (Mvskoke)", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed Dec. 22, 2009

- ^ The tribe has made clear that their official name remains the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and it is not wrong for someone to use the word "Creek"; but, the change to "Muscogee Nation" was made for advertising and marketing purposes. "The Muscogee Nation is dropping "Creek" from its name. Here's why". Michael Overall, Tulsa World, May 6, 2021. May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Theodore Isham and Blue Clark. "Creek (Mvskoke)", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed Dec. 22, 2009

- ^ Innes, 393

- ^ Higgins, Tucker; Mangan, Dan (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court says eastern half of Oklahoma is Native American land". CNBC. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Dictionary

- ^ a b "MCN Governmental Branches." Muscogee Nation. 2008 (retrieved 22 Dec 2009)

- ^ "Creek Supreme Court"

- ^ "M(C)N Bar Association"

- ^ a b "Muscogee (Creek) Nation Citizenship Facts and Stats"

- ^ "Muscogee (Creek) Nation Citizenship"

- ^ "Muscogee Nation judge rules in favor of citizenship for slave descendant". Law. NPR. Associated Press. September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ a b [1] Muscogee (Creek) Nation Citizenship Office. Retrieved 8 Mar 2017. (archived)

- ^ "Division of Health", Muscogee (Creek) Nation. (retrieved 28 Dec 2009)

- ^ "Lighthorse Tribal Police." Muscogee (Creek) Nation. (retrieved 28 Dec 2009)

- ^ "About MFSI." Mvskoke Food Sovereignty Initiative. (retrieved 28 Dec 2009)

- ^ "Quick Facts" (PDF). Mvskoke Tourism & Recreation. March 8, 2017.

- ^ "MNBE". MNBE. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Onefire Holdings | Tulsa, Oklahoma". onefireholding.com. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Creek Council House Museum." Attractions in Okmulgee, Oklahoma. (retrieved 22 Dec 2009)

- ^ Clifton Adcock, "Creeks ask to buy Council House: The U.S. sold it out from under them to the city of Okmulgee in 1919. It's now a museum.", Tulsa World, March 18, 2010.

- ^ [2]"Creek National Capitol" (Retrieved 20 Feb 2021)

- ^ College of the Muscogee Nation "FAQ". (retrieved 20 Feb 2021)

- ^ Congressional Edition - United States. Congress - 1888 Exhibit E. State of Indian Territory, County of Creek Nation : Before me, ... Sarah Davis (her x mark).

- ^ "The Fourteenth Creek Treaty", concluded at Washington, D. C., on the 7th of August, 1856, was one of the most important in the history of the Creek. The names of the Creek delegates who signed it: Tuckabatchee Minco, Echo Harjo, Chilly McIntosh and Daniel N. McIntosh (sons of chief William McIntosh, who was executed in 1825 for signing the Treaty of Indian Springs), Benjamin Marshall, and George W. Stidham. These names continue to be prominent in the Creek Nation. Their descendants are among the leaders of the present generation of Creek. This treaty is an attempted summary of all former treaties, canceling many old provisions that seemed to have outlived their usefulness and adjusting many disputes which had arisen during the preceding decade. Chronicles of Oklahoma

- ^ Morton, Ohland (March 1931). "Early History of the Creek Indians". Oklahoma Historical Society. Chronicles of Oklahoma. p. 25. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Creek Indians in the American Civil War

- ^ 1870 Loyal Creek abstract - Creek Treaty - Article IV provides how the losses of the loyal Creeks are to be ascertained ... and a roll of the names of all soldiers that enlisted in the Federal army, loyal refugee Indians ...

- ^ Note: Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and American Indians: The Amendment was intended to give citizenship to African-American former slaves and not to Indians, who were considered to have independent sovereignty and citizenship within the territories of their reservations. Government agencies (the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Department of the Interior), and the courts (state, federal, and, ultimately, the Supreme Court) consistently held that the Fourteenth Amendment did not confer citizenship on Indians. Under the Constitution, and the Supreme Court's interpretation of the Constitution, Indian tribes were classified as "domestic dependent nations," and therefore, Indians were tribal citizens, not United States citizens.

- ^ Sessional indexes to the Annals of Congress: Register of Debates in Congress ... By United States Historical Documents: 1914 Reference, Creek Nation: to Investigate relative to duplicate and fraudulent enrollments in (see Ы. J. Res. 3SS>. 329.b

- ^ McKay v Cambell The negro and his descendants never had been considered a part of the free inhabitants ... McKay v. Campbell. 2 7 was another case in which an opinion was given on the clause in ... II. Status and Disabilities - INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND .Doe v. Avaline, 8 Ind., 6. The term "mestizo" signifies the issue of a negro and an Indian. Miller v. Dawson .... Osborn, 2 Fed., 58; 6 Sawy., 406; McKay v. Campbell, 16 Fed. Cas., No. 8840 ...

- ^ United States Courts of Appeals reports: Cases adjudged ..Circuit Courts of Appeals, Samuel Appleton Blatchford - 1895 - Law reports, digests, etc Cases adjudged in the United States Circuit Court of Appeals. v. ... J. P. Davison, one of Julia's children, was appointed administrator of her ... Caldwell, Circuit Judge, after stating the DAVISON v. GIBSON. 363.

- ^ DAVISON V. WALKER.. of J. P. Davison, guardian of Sally McIntosh v. said Walker, involving the N. Q ...

- ^ IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATION. FILED. Ron Graham,. OKMULGEE DISTRICT. Plaintiff,. ) v. 1. ) Muscogee (Creek) Nation. ) Citizenship Board,. ) ) Defendant. ) and. Fred Johnson, ...

- ^ Muscogee Creek Nation Official Tribal Website: Freedmen descendants want their own tribe

- ^ MASON et al v. SALAZAR et al :: Justia Dockets & Filings Apr 27, 2012 – ... al v. SALAZAR et al - Justia Federal Dockets and Filings. ... KELVIN MASON, JAMES MASON, NATALEE MILLER and GRANT PERRYMAN ...

- ^ "Grant-Lee Phillips." Archived September 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The Ark. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

References

[edit]- Innes, Pamela. "Creek in the West." William C. Sturtevant, editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 14, Southeast. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Associate Justice Richard C. Lerblance - Descendants of Elijah Hermogene Lerblance

External links

[edit]- The Muscogee Nation, official website

- Mvskoke Etlvlwv Nakcokv Mvhakv Svhvlwecvt (College of the Muscogee Nation)

- Muscogee Nation District Court

- "Creek (Mvskoke)," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- Muscogee (Creek) Indian Territory Project, OK/ITGenWeb Project.

- Muscogee (Creek) Nation

- Native American tribes in Oklahoma

- American Indian reservations in Oklahoma

- Federally recognized tribes in the United States

- Creek County, Oklahoma

- Hughes County, Oklahoma

- Okfuskee County, Oklahoma

- Okmulgee County, Oklahoma

- McIntosh County, Oklahoma

- Muskogee County, Oklahoma

- Tulsa County, Oklahoma

- Wagoner County, Oklahoma