Pamiris

Pōmērə (Shughni) | |

|---|---|

Flag used by the Pamiri people | |

A Pamiri girl photographed in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan (2018) | |

| Total population | |

| c. 300,000–350,000[1] (2006) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tajikistan (Gorno-Badakhshan) | approx. 200,000 (2013)[2] |

| Afghanistan (Badakhshan) | 65,000[3] |

| China (Xinjiang) | 50,265[4] |

| Russia (Moscow) | 32,000 (2018)[5] |

| Pakistan (Gilgit-Baltistan) | Unknown |

| Languages | |

| Pamiri Secondary: Persian (Dari and Tajik), Russian, Urdu, Uyghur | |

| Religion | |

| Mainly Islam (predominantly Nizari Isma'ili Shia Islam, minority Sunni Islam) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranian peoples | |

The Pamiris[a] are an Eastern Iranian ethnic group, native to Central Asia, living primarily in Tajikistan (Gorno-Badakhshan), Afghanistan (Badakhshan), Pakistan (Gilgit-Baltistan) and China (Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County). They speak a variety of different languages, amongst which languages of the Eastern Iranian Pamir language group stand out. The languages of the Shughni-Rushani group, alongside Wakhi, are the most widely spoken Pamiri languages.[6]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]

Eastern Iranian (mainly Saka (Scythian)), Tocharian, and probably Dardic tribes, as well as pre-Indo-European substrate populations took part in the formation of the Pamiris: in the 7th and 2nd centuries BC the Pamir Mountains were inhabited by tribes known in written sources as the Sakas.[7][1][8] They were divided into different groupings and recorded with various names, such as Saka Tigraxauda ("Saka who wear pointed caps"), Saka Haumavarga ("Saka who revere hauma"), Saka Tvaiy Paradraya ("Saka who live beyond the (Black) Sea"), Saka Tvaiy Para Sugdam ("Saka who are beyond Sogdia").[9][10]

The version about Pamiris' Hephthalite origin was put forward by the famous Soviet and Russian anthropologist Lev Gumilev (d. 1992).[11]

The Western Pamirs, which was defending itself from the invasion of eastern nomads, became the eastern outpost of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom from the middle of the 3rd century BC, and the Kushan Empire from the middle of the 1st century AD.[7][12] Nomadic cattle breeding developed in the Eastern Pamirs, while agriculture and pastoralism developed in the Western Pamirs.[7] Remains of ancient fortresses and border fortifications of the Bactrian and Kushan periods are still preserved in the Pamirs.[12] The oldest Saka burials have also been found in the Eastern Pamirs.[13]

Middle Ages

[edit]Mass migration particularly strengthened after the 5th and 6th centuries because of the Turkic movement into Central Asia (and the Mongols afterwards) from whom the settled Iranian population escaped in canyons that were not attractive for cattle-breeding needed wildest.[14] Vasily Bartold (d. 1930), in his work "Turkistan" mentions that in the 10th century three Pamiri states: Wakhan, Shikinan (Shughnan) and Kerran (probably Rushan and Darvaz) have already been settled by pagans, however in the political realm, probably, were subjugated by Muslims. In the 12th century, Badakhshan was annexed to the Ghurid state.[15] Between the 10 and 16th centuries Wakhan, Shughnan and Rushan together with Darvaz (the last two were united in the 16th century) were governed by the local feudal dynasties and actually were independent.[16][17][18]

Modern history

[edit]In 1895, Badakhshan was divided between Afghanistan, which was under British influence, and the Emirate of Bukhara, which was under the protectorate of the Tsarist Russian Empire.[7][19][17] The central lands of Badakhshan, however, remained on the Afghan side of the demarcation line.[19][20] On 2 January 1925, the Soviet government decided to create a new geographical and political entity known in modern times as the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast' (GBAO). During the Soviet period Pamiris were generally excluded from positions of power within the republic, with a few exceptions, notably Shirinshoh Shotemur, a Shughni who held the position of chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic during the 1930s; and Nazarshoh Dodkhudoev, a Rushani who served as chairman of the Presidium of the Tajik Supreme Soviet in the 1950s.[21] Literacy in GBAO increased from 2% in 1913 to almost 100% in 1984.[22]

In the 1926 census the Pamiris were labelled as "Mountain Tajiks", in the 1937 and 1939 censuses they appeared as separate ethnic groups within the Tajiks, in the 1959, 1970 and 1979 censuses they were classified as Tajiks.[7] In the late 1980s Pamiri identity was further solidified through efforts to elevate the status of Pamiri languages and to promote literature in the Pamiri languages, as well as 'claims of sovereignty and republic status for Badakhshan' made by Pamiri intellectuals.[21] In 1991, after the fall of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), GBAO remained part of the newly independent country of Tajikistan.[19]

On 4 March 1991 the Pamiri political group La'li Badakhshan (Tajik: Лаъли Бадахшон, lit. 'the ruby of Badakhshan') was formed in Dushanbe.[23][24][25] The founder of this organization was Atobek Amirbekov, a Pamiri born in Khorog who had worked at the Dushanbe Pedagogical Institute as a lecturer and deputy dean.[23][25] The backbone of the organisation were students of higher educational institutions of the capital and Pamiri youth living in the Tajik capital.[24][26] La'li Badakhshan's primary objective was to represent the cultural interests of the Pamiri people and to advocate for greater autonomy for the GBAO. The group also participated in and organised numerous demonstrations in Dushanbe and Khorog during the first year of independence in Tajikistan.[23]

Since the end of 1992, the Pamiris' national movement has declined, which was primarily due to the sharp deterioration of socio-economic conditions and the civil war (1992–1997) that unfolded in Tajikistan.[27][28][29] Together with Gharmis, the Pamiris were part of the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), a coalition of different nationalist, liberal democratic and Islamist parties. A United Nation investigation reported that in December 1992 in Dushanbe "buses were routinely searched, and persons with identity cards revealing they were of Pamiri or Gharmi origin were forced out and either killed on the spot or taken away and later found dead or never heard from again."[30]

The self-proclaimed Autonomous Republic of Badakhshan formally existed until November 1994.[31] According to Suhrobsho Davlatshoev, "the Tajikistani civil war crystallized and strengthened the ethnic consciousness of Pamiris in some respect."[29]

Starting in the 2020s, the Tajikistani government cracked down on Pamiri activism, cultural practices, and institutions, as well as the use of the Pamiri language.[32] Subsequently, there was an exodus of ethnic Pamiris from Tajikistan and Russia.[33]

Identity

[edit]As Alexei Bobrinsky's records testify, during his discussions with the Pamiris in the beginning of the 20th century, Pamiris underlined their Iranian origin.[34] Although the Soviet ethnographers called the Pamiris as "Mountain Tajiks" the majority of the Pamiri intelligentsia see themselves as belonging to a separate and distinct ethnos.[35][36] In China, the same people are officially deemed to be Tajiks. Not so long ago the same was true in Afghanistan where they were identified as Tajiks, but more recently the Afghan government reclassified them as Pamiris.[37]

Religion

[edit]Pre-Islamic beliefs

[edit]Before the spread of Islam in the Pamirs, the Pamiris professed faith in various belief systems. Legends and some current stories about fire worshipping and veneration of the sun and the moon indicate the possibility of some continuation of pre-Islamic religious practices, such as mehrparastī (a pre-Islamic practice of worshipping the sun and the moon), and Manichaean and Zoroastrian customs and rites in the Pamirs.[38][39] Zoroastrianism was a dominant religion and tradition for thousands of years, such that many of its traditions survived including specific features of the Nowruz (Iranian New Year) celebrations and of Pamiri houses, graveyards, burial rites and customs, as well as Avestan toponyms.[40] In Shugnan and Wakhan, Zoroastrian temples were active until the late Middle Ages.[7]

The town of Sikāshim [modern Ishkashim on both the Tajik and Afghan sides] is the capital of the region of Wakhān (gaṣabi-yi nāhiyyat-i Wakhān). Its inhabitants are the fire-worshipers (gabrakān) and the Muslims, and the ruler (malik) of Wakhān lives there. Khamdud [Khandut in modern Afghan Wakhān] is where the idol temples of the Wakhis (butkhāna-yi Wakhān) are located.[41]

Nasir Khusraw and Fatimid Isma'ilism

[edit]

The spread of Isma'ili Shi'i Islam is associated with the stay in the Pamirs of Nasir Khusraw (d. 1088), a Persian-speaking poet, theologian, philosopher, and missionary (da'i) for the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate, who was hiding from a Sunni fanaticism in Shughnan.[7][42][43] Many religious practices are associated with Nasir's mission by the Pamiri Isma'ili community to this day, and people in the community venerate him as a hazrat [majesty], hakim [sage], shah [king], sayyid [descendant of the Prophet], pir-i quddus [holy saint], and hujjat [proof].[44][45] The community also considers him to be a member of the Prophet Muhammad's family, the Ahl al-Bayt.[45][46]

As Lydia Monogarova asserts, one of the main reasons why Pamiris accepted Isma'ilism can be seen as their extreme tolerance to various beliefs compared to the other sects of Islam.[47] As a result, terms such as Daʿwat-i Nāṣir or Daʿwat-i Pīr Shāh Nāṣir are prevalent designations among the Isma'ilis in Tajik and Afghan Badakhshan, the northern areas of Pakistan and certain parts of Xinjiang province in China.[42][48] The Isma'ilis of Badakhshan and their offshoot communities in the Hindu Kush region, now situated in Hunza and other northern areas of Pakistan, regard Nasir as the founder of their communities.[43]

Marco Polo (d. 1324), when passed through Wakhan in 1274 referred to the population here as Muslims.[49]

The five Iranian da'is

[edit]In the Pamirs, there is a story about five Iranian Isma'ili da'i brothers sent by the Nizari Imams: Shah Khamush, Shah Malang, and Shah Kashan, who settled in Shughnan; and Shah Qambar Aftab and Shah Isam al-Din, who settled in Wakhan.[50][51][52] They likely introduced themselves as qalandars, because even today, they are remembered by the Pamiris as the "Five Qalandars".[53] The most detailed biographical narrative of Shah Khamush is found in Fadl Ali-Beg Surkh-Afsar's appendix to the Tāʾrikh-i Badakhshān of Mirza Sangmuhammad Badakhshi. For instance, Surkh-Afsar claims that the aforementioned Shah Khamush ('the silent king'), referred to as Sayyid Mīr Ḥasan Shāh, who traced his descent to Musa al-Kazim (d. 799), the seventh Imam of the Twelver Shi'is, was an uwaisi saint (wali) from his mother's line, migrated from Isfahan to Shughnan in the 11th century, and that he was the ancestor of Shughnan's pirs and mirs.[54][55][56] This story was narrated to Bobrinsky, one of the Russian pioneers of Pamiri studies, by the Shughni pir Sayyid Yūsuf ʿAlī Shāh in 1902.[53]

Dīn-i Panj-tanī

[edit]During the concealment period (dawr al-satr), which continued in Isma'ili history for several centuries (from the Alamut collapse until the Anjudan revival), several elements of the Twelver Shi'i and Sufi ideas became mixed with the Isma'ili belief of the Pamiris.[57][58] Many Persian-speaking poets and philosophers, such as Ansari, Sanai, Attar, and Rumi, are considered by Pamiri Isma'ilis as their co-religionists and are regarded as pīran-i maʿrifat (lit. 'the masters of gnosis').[59][57] Recognizing as their leaders Muhammad, his daughter Fatima, son-in-law Ali and grandsons Hasan and Husayn, the Pamiris call their religion "Dīn-i Panj-tanī" (lit. 'the religion of the [holy] five ') and perceive themselves as the followers of this religion, which they name as "Panj-tan".[60][61][62]. The 15 century Shughni poet Shāh Ẓiyāyī praises Imām ʿAlī, Imām Ḥusayn, Imām Ḥasan and Fāṭima, whom he calls the Panj-tan, in a poem "Muḥammad-astu ʿAlī Fāṭima Ḥusayn-u Ḥasan" that is well known in Badakhshan.[63]

The label Chār-yārī (lit. 'followers of the four friends') is used by the Pamiri Isma'ilis to refer to the Sunni Muslims who acknowledge the first four caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali).[64][65] Shāh Ẓiyāyī regards those who have faith in the Panj-tan as true believers, unlike those who only say "four four" (chār chār), i.e. the Sunnis.[63]

The use of the term Dīn-i Panj-tanī, a local equivalent of the term Shi'a in the context of Badakhshan, expresses an allegiance to the Shi'a, in general, and to Isma'ilism, in particular.[66][67]

Chirāgh-Rāwshan

[edit]Amongst the Pamiri Isma'ilis there is distinctive practice called Chirāgh-Rāwshan (lit. 'luminous lamp'), which was probably introduced by Nasir Khusraw as a means of attracting people to attend his lectures.[46][68][69] The practice is also known as tsirow/tsiraw-pithid/pathid in Pamiri languages; the recitation text called Qandīl-Nāma or Chirāgh-Nāma (lit. 'the Book of Candle'), consist of certain Qur'anic verses and several religious lyrics in Persian, which are attributed to Nasir Khusraw.[70][71] Chirāgh-Rāwshan is also a custom prevalent among the Isma'ilis of the northern areas of Pakistan and some parts of Afghanistan.[72]

O insightful lover, join the mission of Nāṣir! O pious believer, join the mission of Nāṣir! Nāṣir is from the family of the Prophet, He is truly the offsprings of ʿAlī.[46]

— Qandīl-Nāma

According to oral tradition, this ritual was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by the angel Gabriel (Jibra'il) to provide comfort for the Prophet at the death of his young son Abd Allah.[73]

Language

[edit]The Pamiris linguistically vary into the Shughni-Rushani group (Shughni, Rushani, Khufi, Bartangi, Roshorvi, Sarikoli), with which Yazghulami and the now extinct Vanji closely linked; Ishkashimi, Sanglechi, and Zebaki; Wakhi; Munji and Yidgha.[74][17][75] Native languages of Pamiris belong to the southeastern branch of Iranian languages.[76][74] However, according to Encyclopædia Iranica, the Pamiri languages and Pashto belong to the North-Eastern Iranian branch.[77]

According to Boris Litvinsky:

The common Shughni-Rushani language existed approximately 1,300–1,400 years ago, but it later split … in much earlier times, however, there was a common Pamiri language which developed into the Shughni-Rushani, Wakhi, Ishkashimi and Munji dialects. And, as a common Shughni-Rushani language existed until the 5–6th centuries CE, a broad Pamiri linguistic communion may have existed during, or around, the Saka period.[10]

The Chinese traveler Xuanzang, who visited Shughnan in the 7th century, claimed that the inhabitants of this region had their own language, different from Tocharian (Bactrian). However, according to him, they had the same script.[78]

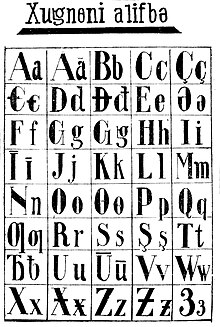

In the 1930s, Pamiri intellectuals tried to create an alphabet for Pamiri languages. They started to create an alphabet for the Shughni language, the most widely spoken language in the Pamirs, based on the Latin script. In 1931, the first textbook in Shughni for adults was published, one of the authors of which was the young Shughni poet Nodir Shambezoda (1908–1991).[79][80]

During the Great Purge in the USSR, Nodir Shanbezoda's collection of poems was destroyed, and he himself was subjected to repression, like other Pamiri intellectuals who had started working by that time. All work on the development of literature and education in Pamiri languages was curtailed.[80] As a result, Pamiri languages became inscriptural for many decades. In 1972, a campaign to destroy books in Pamiri languages was carried out at the Ferdowsi State Public Library in Dushanbe.[81][82] As Tohir Kalandarov notes, "this remains a black spot in Tajikistan's history."[82]

Although Pamiri languages belong to the same group of Eastern-Iranian languages they exclude common understanding among themselves.[76] Tajik language, called as forsi (Persian) by Pamiris, was used for communication as between them and with neighboring peoples as well.[76][83][84] Though Shughni communities are habitually spread only in Tajikistan and Afghanistan traditionally Shughni language is spread among all Pamiris as a lingua franca.[85]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Лашкарбеков 2006, pp. 111–30.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "Pamiri Tajiks and Yaghnobis | Facts and Details". Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "What Languages do People Speak in Afghanistan?". World population review. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "新疆维吾尔自治区统计局". 11 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Додыхудоева 2018, p. 108.

- ^ "What Languages do People Speak in Afghanistan?". World population review. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Каландаров 2014.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Мамадназаров 2015, p. 386.

- ^ a b Zoolshoev 2022.

- ^ Мамадназаров 2015, p. 387.

- ^ a b Nazarkhudoeva 2015, p. 102.

- ^ Лашкарбеков 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, pp. 37–8.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 40.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Iloliev 2022, p. 47.

- ^ Straub 2014, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Daudov, Shorokhov & Andreev 2018, p. 804.

- ^ a b Straub 2014, p. 177.

- ^ Daudov, Shorokhov & Andreev 2018, p. 805.

- ^ a b c Straub 2014, p. 179.

- ^ a b Худоёров 2011, p. 79.

- ^ a b Kılavuz 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Daudov, Shorokhov & Andreev 2018, p. 817.

- ^ Худоёров 2011, p. 80.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, pp. 91, 94.

- ^ a b Davlatshoev 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Straub 2014, pp. 181–2.

- ^ Худоёров 2011, p. 81.

- ^ "Tajikistan: Freedom in the World 2024 Country Report". Freedom House. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Pair of Pamiri Activists Disappear From Russia and Reappear in Tajikistan". The Diplomat. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 97.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 102.

- ^ Додыхудоева 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Dagiev 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Goibnazarov 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Мамадназаров 2015, p. 402.

- ^ Dagiev 2022, p. 88.

- ^ Iloliev 2008, p. 29.

- ^ a b Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 147.

- ^ a b Daftary 2007, p. 207.

- ^ Dagiev 2022, pp. 18–9.

- ^ a b Goibnazarov 2017, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Iloliev 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 50.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, pp. 44, 48.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 44.

- ^ Iloliev 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Goibnazarov 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 155.

- ^ a b Goibnazarov 2017, p. 35.

- ^ Iloliev 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Dagiev 2022, pp. 27–8.

- ^ Elnazarov & Aksakolov 2011, p. 48.

- ^ a b Iloliev 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Goibnazarov 2017, pp. 35–6.

- ^ Goibnazarov 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Davlatshoev 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 124.

- ^ Iloliev 2008, pp. 36, 41–2.

- ^ a b Gulamadov 2018, p. 82.

- ^ Elnazarov & Aksakolov 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Goibnazarov 2017, p. 38.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, pp. 24, 124.

- ^ Gulamadov 2018, pp. 81, 82.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 221.

- ^ Elnazarov & Aksakolov 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Iloliev 2022, p. 54.

- ^ Goibnazarov 2017, p. 36.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 216.

- ^ Elnazarov & Aksakolov 2011, p. 68.

- ^ a b Steblin-Kamenski 1990.

- ^ Dodykhudoeva 2004, pp. 149, 150.

- ^ a b c Davlatshoev 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Sims-Williams 1996.

- ^ Лашкарбеков 2006, p. 64.

- ^ Каландаров 2018, pp. 166, 167.

- ^ a b Эдельман 2016, p. 95.

- ^ Эдельман 2016, p. 96.

- ^ a b Каландаров 2018, p. 170.

- ^ Моногарова 1965, p. 27.

- ^ Nourmamadchoev 2014, p. 37, 38.

- ^ Dodykhudoeva 2004, p. 149.

Bibliography

[edit]English sources

[edit]- Steblin-Kamenski, I. M. (1990). "Central Asia xiii. Iranian Languages". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 2–3. pp. 223–226.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1996). "Eastern Iranian languages". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. VII. pp. 649–652.

- Dodykhudoeva, L. R. (2004). "Ethno-cultural heritage of the peoples of West Pamir". Collegiuim Antropologicum. 1: 147–159.

- Davlatshoev, Suhrobsho (2006). The formation and consolidation of Pamiri ethnic identity in Tajikistan. Middle East Technical University.

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Ismā'īlīs: Their History and Doctrines (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511355615.

- Iloliev, Abdulmamad (2008). The Ismaili-Sufi Sage of Pamir: Mubarak-i Wakhani and the Esoteric Tradition of the Pamiri Muslims. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-934043-97-4.

- Elnazarov, Hakim; Aksakolov, Sultonbek (2011). "The Nizari Ismailis of Central Asia in Modern Times". In Daftary, Farhad (ed.). A Modern History of the Ismailis: Continuity and Change in a Muslim Community. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-717-7.

- Nourmamadchoev, Nourmamadcho (2014). The Ismāʿīlīs of Badakhshan: History, Politics and Religion from 1500 to 1750. London: School of Oriental and African Studies.

- Kılavuz, I. T. (2014). Power, Networks and Violent Conflict in Central Asia: A Comparison of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815377931.

- Straub, D. P. (2014). Akyildiz, Sevket; Carlson, Richard (eds.). Social and Cultural Change in Central Asia. Central Asia Research Forum (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781138575615.

- Nazarkhudoeva, D. S. (2015). "The current stage of development of ethnic identity and ethnic relations of the people of the Pamir". Moscow State Art and Cultural University. 1: 63. ISSN 1997-0803.

- Goibnazarov, Chorshanbe (2017). Qasīda-khonī: A Musical Expression of Identities in Badakhshan, Tajikistan Tradition, Continuity, and Change. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- Gulamadov, Shaftolu (2018). The Hagiography of Nāṣir-i Khusraw and the Ismāʿīlīs of Badakhshān. University of Toronto. ISBN 9780438188624.

- Dagiev, Dagikhudo (2018). Identity, History and Trans-Nationality in Central Asia. Central Asian Studies. Routledge.

- Daudov, A. K; Shorokhov, V. A; Andreev, A. A. (2018). "Anatomy of the Political Transformations during the Period of the Dissolution of the USSR on the Material from Kūhistoni Badakhshon" (PDF). Saint Petersburg University. 63 (3): 799–822. doi:10.21638/11701/spbu02.2018.309. ISSN 1812-9323.

- Zoolshoev, M. Z. (2022). Ancient and Early Medieval Kingdoms of the Pamir Region of Central Asia (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1032246765.

- Dagiev, Dagikhudo (2022). Central Asian Ismailis: An Annotated Bibliography of Russian, Tajik and Other Sources. Ismaili Heritage. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-7556-4498-8.

- Iloliev, Abdulmamad (2022). "Ismaili Revival in Tajikistan: From Perestroika to the Present". Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi (102): 43–60. doi:10.34189/hbv.102.002. ISSN 1306-8253.

Russian sources

[edit]- Моногарова, Л. Ф. (1965). Современные этнические процессы на Западном Памире (in Russian). Советская этнография.

- Лашкарбеков, Б. Б. (2006). Памирская экспедиция (статьи и материалы полевых исследований) (in Russian). Москва: Институт востоковедения РАН. ISBN 5892822915.

- Худоёров, М. М. (2011). "Проблема Памирской автономии в Таджикистане на рубеже 1980—1990-х годов". Magistra Vitae: электронный журнал по историческим наукам и археологии (in Russian). 22 (237): 78–81.

- Каландаров, Тохир (2014). "Памирские народы". Большая российская энциклопедия (in Russian). Москва. pp. 178–179.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Мамадназаров, Мунавар (2015). Памятники зодчества Таджикистана (in Russian). Москва: Прогресс-Традиция. ISBN 978-5-89826-459-8.

- Эдельман, Д. И. (2016). "Некоторые проблемы миноритарных языков Памира". Родной язык (in Russian): 88–112.

- Каландаров, Т. С. (2018). "Памирские народы, их языки и перепись: этнический дискурс". Этнографическое обозрение (in Russian): 162–178. doi:10.31857/S086954150001482-0.

- Додыхудоева, Л. Р. (2018). "Влияние городской среды на носителей памирских языков". Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. Труды института лингвистических исследований (in Russian). XIV (3): 108–136. ISSN 2306-5737.