Great Trek

The Great Trek (Afrikaans: Die Groot Trek [di ˌχruət ˈtrɛk]; Dutch: De Grote Trek [də ˌɣroːtə ˈtrɛk]) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial administration.[1] The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers, known collectively as Boers, and the British Empire.[2] It was also reflective of an increasingly common trend among individual Boer communities to pursue an isolationist and semi-nomadic lifestyle away from the developing administrative complexities in Cape Town.[3] Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as voortrekkers (/ˈfʊərtrɛkərz/,[4] Afrikaans: [ˈfuərˌtrɛkərs]), meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" (literally "fore-trekkers") in Dutch and Afrikaans.

The Great Trek led directly to the founding of several autonomous Boer republics, namely the South African Republic (also known simply as the Transvaal), the Orange Free State, and the Natalia Republic.[5] It also led to conflicts that resulted in the displacement of the Northern Ndebele people,[6] and conflicts with the Zulu people that contributed to the decline and eventual collapse of the Zulu Kingdom.[3]

Background

[edit]

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Cape of Good Hope area was populated by Khoisan tribes.[7] The first Europeans settled in the Cape area under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company (also known by its Dutch initials VOC), which established a victualling station there in 1652 to provide its outward bound fleets with fresh provisions and a harbour of refuge during the long sea journey from Europe to Asia.[8] In a few short decades, the Cape had become home to a large population of "vrijlieden", also denoted as "vrijburgers" (free citizens), former Company employees who remained in Dutch territories overseas after completing their contracts.[9] Since the primary purpose of the Cape settlement at the time was to stock provisions for passing Dutch ships, the VOC offered grants of farmland to its employees under the condition they would cultivate grain for the Company warehouses, and released them from their contracts to save on their wages.[8] Vrijburgers were granted tax-exempt status for 12 years and loaned all the necessary seeds and farming implements they requested.[10] They were married Dutch citizens, considered "of good character" by the Company, and had to commit to spending at least 20 years on the African continent.[8] Reflecting the multi-national character of the VOC's workforce, some German soldiers and sailors were also considered for vrijburger status as well,[8] and in 1688 the Dutch government sponsored the resettlement of over a hundred French Huguenot refugees at the Cape.[11] As a result, by 1691 over a quarter of the colony's European population was not ethnically Dutch.[12] Nevertheless, there was a degree of cultural assimilation through intermarriage, and the almost universal adoption of the Dutch language.[13] Cleavages were likelier to occur along social and economic lines; broadly speaking, the Cape colonists were delineated into Boers, poor farmers who settled directly on the frontier, and the more affluent, predominantly urbanised Cape Dutch.[14]

Following the Flanders Campaign and the Batavian Revolution in Amsterdam, France assisted in the establishment of a pro-French client state, the Batavian Republic, on Dutch soil.[2] This opened the Cape to French warships.[3] To protect her own prosperous maritime shipping routes, Great Britain occupied the fledgling colony by force until 1803.[2] From 1806 to 1814, the Cape was governed as a British military dependency, whose sole importance to the Royal Navy was its strategic relation to Indian maritime traffic.[2] The British formally assumed permanent administrative control around 1815, as a result of the Treaty of Paris.[2]

Causes

[edit]At the onset of the British rule, the Cape Colony encompassed 100,000 square miles (260,000 km2) and was populated by about 26,720 people of European descent, a relative majority of whom were of Dutch origin.[2][12] Just over a quarter were of German ancestry and about one-sixth were descended from French Huguenots,[12] although most had ceased speaking French since about 1750.[13] There were also 30,000 African and Asian slaves owned by the settlers, and about 17,000 indigenous Khoisan. Relations between the settlers – especially the Boers – and the new administration quickly soured.[5] The British authorities were adamantly opposed to the Boers' ownership of slaves and what was perceived as their unduly harsh treatment of the indigenous peoples.[5]

The British government insisted that the Cape finance its own affairs through self-taxation, an approach which was alien to both the Boers and the Dutch merchants in Cape Town.[3] In 1815, the controversial arrest of a white farmer for allegedly assaulting one of his servants resulted in the abortive Slachter's Nek Rebellion. The British retaliated by hanging at least five Boers for insurrection.[2] In 1828, the Cape governor declared that all native inhabitants but slaves were to have the rights of "citizens", in respect of security and property ownership, on parity with the settlers. This had the effect of further alienating the colony's white population.[2][15] Boer resentment of successive British administrators continued to grow throughout the late 1820s and early 1830s, especially with the official imposition of the English language.[6] This replaced Dutch with English as the language used in the Cape's judicial and political systems, putting the Boers at a disadvantage, as most spoke little or no English.[2][15]

Britain's alienation of the Boers was particularly amplified by the decision to abolish slavery in all its colonies in 1834.[2][3] All 35,000 slaves registered with the Cape governor were to be freed and given rights on par with other citizens, although in most cases their masters could retain them as apprentices until 1838.[15][16] Many Boers, especially those involved with grain and wine production, were dependent on slave labour; for example, 94% of all white farmers in the vicinity of Stellenbosch owned slaves at the time, and the size of their slave holdings correlated greatly to their production output.[16] Compensation was offered by the British government, but payment had to be received in London, and few Boers possessed the funds to make the trip.[3]

Bridling at what they considered an unwarranted intrusion into their way of life, some in the Boer community considered selling their farms and venturing deep into South Africa's unmapped interior to preempt further disputes and live completely independent from British rule.[3] Others, especially trekboers, a class of Boers who pursued semi-nomadic pastoral activities, were frustrated by the apparent unwillingness or inability of the British government to extend the borders of the Cape Colony eastward and provide them with access to more prime pasture and economic opportunities. They resolved to trek beyond the colony's borders on their own.[6]

Opposition

[edit]Although it did nothing to impede the Great Trek, Great Britain viewed the movement with pronounced trepidation.[14] The British government initially suggested that conflict in the far interior of Southern Africa between the migrating Boers and the Bantu peoples they encountered would require an expensive military intervention.[14] However, authorities at the Cape also judged that the human and material cost of pursuing the settlers and attempting to re-impose an unpopular system of governance on those who had deliberately spurned it was not worth the immediate risk.[14] Some officials were concerned for the tribes the Boers were certain to encounter, and whether these tribes would be enslaved or otherwise reduced to a state of penury.[17]

The Great Trek was not universally popular among the settlers either. Around 12,000 of them took part in the migration, about a fifth of the colony's Dutch-speaking white population at the time.[3][1] The Dutch Reformed Church, to which most of the Boers belonged, explicitly refused to endorse the Great Trek.[3] Despite their hostility towards the British, there were Boers who chose to remain in the Cape of their own accord.[5]

For its part, the distinct Cape Dutch community had accepted British rule; many of its members even considered themselves loyal British subjects with a special affection for English culture.[18] The Cape Dutch were also much more heavily urbanised and therefore less likely to be susceptible to the same rural grievances and considerations as those held by the Boers.[14]

Exploratory treks to Natal

[edit]In January 1832, Andrew Smith (an Englishman) and William Berg (a Boer farmer) scouted Natal as a potential colony. On their return to the Cape, Smith waxed very enthusiastic, and the impact of discussions Berg had with the Boers proved crucial. Berg portrayed Natal as a land of exceptional farming quality, well watered, and nearly devoid of inhabitants.

In June 1834, the Boer leaders of Uitenhage and Grahamstown discussed a Kommissietrek ('Commission Trek') to visit Natal and to assess its potential as a new homeland for the Cape Boers who were disenchanted with British rule at the Cape. Petrus Lafras Uys was chosen as trek leader. In early August 1834, Jan Gerritze Bantjes set off with some travellers headed for Grahamstown 220 kilometres (140 mi) away, a three-week journey from Graaff-Reinet. Sometime around late August 1834 Jan Bantjes arrived in Grahamstown, contacted Uys and made his introductions.

In June 1834 at Graaff-Reinet, Jan Gerritze Bantjes heard about the exploratory trek to Port Natal and, encouraged by his father Bernard Louis Bantjes, sent word to Uys of his interest in participating. Bantjes wanted to help re-establish Dutch independence over the Boers and to get away from British law at the Cape. Bantjes was already well known in the area as an educated young man fluent both in spoken and written Dutch and in English. Because of these skills, Uys invited Bantjes to join him. Bantjes's writing skills would prove invaluable in recording events as the journey unfolded.

On 8 September 1834, the Kommissietrek of 40 men and one woman, as well as a retinue of coloured servants, set off from Grahamstown for Natal with 14 wagons. Moving through the Eastern Cape, they were welcomed by the Xhosa who were in dispute with the neighbouring Zulu King Dingane ka Senzangakhona, and they passed unharmed into Natal. They travelled more or less the same route that Smith and Berg had taken two years earlier.

The trek avoided the coastal route, keeping to the flatter inland terrain. The Kommissietrek approached Port Natal from East Griqualand and Ixopo, crossing the upper regions of the Mtamvuna and Umkomazi rivers. Travel was slow due to the rugged terrain, and since it was the summer, the rainy season had swollen many of the rivers to their maximum. Progress required days of scouting to locate the most suitable tracks to negotiate. Eventually, after weeks of extraordinary toil, the small party arrived at Port Natal, crossing the Congela River and weaving their way through the coastal forest into the bay area. They had travelled a distance of about 650 kilometres (400 mi) from Grahamstown. This trip would have taken about 5 to 6 months with their slow moving wagons. The Drakensberg route via Kerkenberg into Natal had not yet been discovered.

They arrived at the sweltering hot bay of Port Natal in February 1835, exhausted after their long journey. There, the trek was soon welcomed with open arms by the few British hunters and ivory traders there such as James Collis, including Reverend Allen Francis Gardiner, an ex-commander of the Royal Navy ship Clinker, who had decided to start a mission station there. After congenial exchanges between the Boers and British sides, the party joined them and invited Dick King to become their guide.

The Boers set up their laager ('wagon fort') camp in the area of the present-day Greyville Racecourse in Durban, chosen because it had suitable grazing for the oxen and horses and was far from the foraging hippos in the bay. Several small streams running off the Berea ridge provided fresh water. Alexander Biggar was also at the bay as a professional elephant-hunter and provided the trekkers with information regarding conditions at Port Natal. Bantjes made notes suggested by Uys, which later formed the basis of his more comprehensive report on the positive aspects of Natal. Bantjes also made rough maps of the bay - although this journal is now missing - showing the potential for a harbour which could supply the Boers in their new homeland.

At Port Natal, Uys sent Dick King, who could speak Zulu, to uMgungundlovu to investigate with King Dingane the possibility of granting them land. When Dick King returned to Port Natal some weeks later, he reported that King Dingane insisted they visit him in person. Johannes Uys, brother of Piet Uys, and a number of comrades with a few wagons travelled toward King Dingane's capital at uMgungundlovu, and after making a laager camp at the mouth of the Mvoti River, they proceeded on horseback, but were halted by a flooded Tugela River and forced to return to the laager.

The Kommissietrek left Port Natal for Grahamstown with a stash of ivory in early June 1835, following more or less the same route back to the Cape, and arrived at Grahamstown in October 1835. On Piet Uys's recommendation, Bantjes set to work on the first draft of the Natalialand Report. Meetings and talks took place in the main church to much approval, and the first sparks of Trek Fever began to take hold. From all the information accumulated at Port Natal, Bantjes drew up the final report on "Natalia or Natal Land" that acted as the catalyst which inspired the Boers at the Cape to set in motion the Great Trek.

First wave

[edit]| Largest first wave trek parties[17]: 162–163 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader | Date of departure | Point of departure | Size | |

| Louis Tregardt | September 1835 | Nine families including the Tregardt family | ||

| Hans van Rensburg | September 1835 | 49 | ||

| Hendrik Potgieter | late 1835 or early 1836 | Over 200 once united with the parties of Sarel Cilliers and Casper Kruger. | ||

| Gerrit Maritz | September 1836 | Graaff-Reinet | Over 700 people including roughly 100 white men | |

| Piet Retief | February 1837 | Albany | Roughly 100 men, women, and children. | |

| Piet Uys | April 1837 | Uitenhage | Over 100 members of the Uys family. | |

The first wave of Voortrekkers lasted from 1835 to 1840, during which an estimated 6,000 people (roughly 20% of the Cape Colony's total population or 10% of the white population in the 1830s) trekked.[17]

The first two parties of Voortrekkers left in September 1835, led by Louis Tregardt and Hans van Rensburg. These two parties crossed the Vaal river at Robert's Drift in January 1836, but in April 1836 the two parties split up, just 110 kilometres (70 mi) from the Soutpansberg mountains, following differences between Tregardt and van Rensburg.[19]

In late July 1836 van Rensburg's entire party of 49, except two children who were saved by a Zulu warrior, were massacred at Inhambane by an impi (a force of warriors) of Manukosi.[20] Those of Tregardt's party that had set up around Soutpansberg moved on to colonise Delagoa Bay, with most of the party, including Tregardt, perishing from fever.[17]: 163

A party led by Hendrik Potgieter trekked out of the Tarka area in either late 1835 or early 1836, and in September 1836 a party led by Gerrit Maritz began their trek from Graaff-Reinet. There was no clear consensus amongst the trekkers on where they were going to settle, but they all had the goal of settling near an outlet to the sea.[17]: 162, 163

Conflict with the Matebele

[edit]In August 1836, despite pre-existing peace agreements with local black leaders, a Ndebele (Matebele) patrol attacked the Liebenberg family part of Potgieter's party, killing six men, two women and six children. It is thought that their primary aim was to plunder the Voortrekkers' cattle. On 20 October 1836, Potgieter's party was attacked by an army of 4,600 Ndebele warriors at the Battle of Vegkop. Thirty-five armed trekkers repulsed the Ndebele assault on their laager with the loss of two men and almost all the trekkers' cattle. Potgieter, Uys and Maritz mounted two punitive commando raids. The first resulted in the sacking of the Ndebele colony at Mosega, the death of 400 Ndebele, and the taking of 7,000 cattle. The second commando forced Mzilikazi and his followers to flee to what is now modern day Zimbabwe.[17]: 163

By spring 1837, five to six large Voortrekker colonies had been established between the Vaal and Orange Rivers with a total population of around 2,000 trekkers.

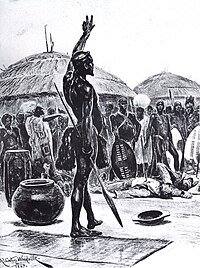

Conflict with the Zulu

[edit]In October 1837 Retief met with Zulu King Dingane to negotiate a treaty for land in what is now Kwa-Zulu Natal. King Dingane, suspicious and untrusting because of previous Voortrekker influxes from across the Drakensberg, had Retief and seventy of his followers killed.[17]: 164

Various interpretations of what transpired exist, as only the missionary Francis Owen's written eye-witness account survived.[21] Retief's written request for land contained veiled threats by referring to the Voortrekker's defeat of indigenous groups encountered along their journey. The Voortrekker demand for a written contract guaranteeing private property ownership was incompatible with the contemporaneous Zulu oral culture which prescribed that a chief could only temporarily dispense land as it was communally owned.[22]

Most versions agree that the following happened: King Dingane's authority extended over some of the land in which the Boers wanted to settle. As prerequisite to granting the Voortrekker request, he demanded that the Voortrekkers return some cattle stolen by Sekonyela, a rival chief. After the Boers retrieved the cattle, King Dingane invited Retief to his residence at uMgungundlovu to finalise the treaty, having either planned the massacre in advance, or deciding to do so after Retief and his men arrived.

King Dingane's reputed instruction to his warriors, "Bulalani abathakathi!" (Zulu for "kill the witches") may indicate that he considered the Boers to wield evil supernatural powers. After killing Retief's delegation, a Zulu army of 7,000 impis were sent out and immediately attacked Voortrekker encampments in the Drakensberg foothills at what later was called Blaauwkrans and Weenen, leading to the Weenen massacre in which 532 people were killed, including 282 Voortrekkers, of whom 185 were children, and 250 Khoikhoi and Basuto accompanying them.[23] In contrast to earlier conflicts with the Xhosa on the eastern Cape frontier, the Zulus killed women and children along with men, wiping out half of the Natal contingent of Voortrekkers.

The Voortrekkers retaliated with a 347-strong punitive raid against the Zulu (later known as the Flight Commando), supported by new arrivals from the Orange Free State. The Voortrekkers were roundly defeated by about 7,000 warriors at Ithaleni, southwest of uMgungundlovu. The well-known reluctance of Afrikaner leaders to submit to one another's leadership, which later hindered sustained success in the Anglo-Boer Wars, was largely to blame.

In November 1838 Andries Pretorius arrived to assist in the defence. A few days later on 16 December 1838, the trekkers fought against Zulu impis at the Battle of Blood River. Pretorius's victory over the Zulu army led to a civil war within the Zulu nation as King Dingane's half-brother, Mpande kaSenzangakhona, aligned with the Voortrekkers to overthrow the king and impose himself. Mpande sent 10,000 impis to assist the trekkers in follow-up expeditions against Dingane.[17]: 164

After the defeat of the Zulu forces and the recovery of the treaty between Dingane and Retief from Retief's body, the Voortrekkers proclaimed the Natalia Republic.[24] After Dingane's death, Mpande was proclaimed king, and the Zulu nation allied with the short-lived Natalia Republic until its annexation by the British Empire in 1843.[17]: 164 [25]

The Voortrekkers' guns offered them a technological advantage over the Zulu's traditional weaponry of short stabbing spears, fighting sticks, and cattle-hide shields. The Boers attributed their victory to a vow they made to God before the battle: if victorious, they and future generations would commemorate the day as a Sabbath. Thereafter, 16 December was celebrated by Boers as a public holiday, first called Dingane's Day, later changed to the Day of the Vow. Post-apartheid, the name was changed to the Day of Reconciliation by the South African government, in order to foster reconciliation between all South Africans.[25]

Impact

[edit]

Conflict amongst the Voortrekkers was a problem because the trek levelled out the pre-existing class hierarchy which had previously enforced discipline, and thus social cohesion broke down. Instead the trek leaders became more reliant on patriarchal family structure and military reputation to maintain control over their parties. This had a large and lasting impact on Afrikaans culture and society.[17]: 163

Centenary celebrations

[edit]The celebration of the Great Trek in the 1930s played a major role in the growth of Afrikaans nationalism. It is thought that the experiences of the Second Boer War and the following period, between 1906 and 1934, of a lack of public discussion about the war within the Afrikaans community helped set the scene for a large increase in interest in Afrikaans national identity. The celebration of the centenary of the Great Trek along with a new generation of Afrikaners interested in learning about the Afrikaans experiences of the Boer War catalysed a surge of Afrikaans nationalism.[17]: 433

The centenary celebrations began with a re-enactment of the trek beginning on 8 August 1938 with nine ox wagons at the statue of Jan van Riebeeck in Cape Town and ended at the newly completed Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria and attended by over 100,000 people. A second re-enactment trek starting at the same time and place ended at the scene of the Battle of Blood River.[17]: 432

The commemoration sparked mass enthusiasm amongst Afrikaners as the re-enactment trek passed through the small towns and cities of South Africa. Both participants and spectators participated by dressing in Voortrekker clothing, renaming streets, holding ceremonies, erecting monuments, and laying wreaths at the graves of Afrikaner heroes. Cooking meals over an open fire in the same way the Voortrekkers did became fashionable amongst urbanites, giving birth to the South African tradition of braaing.[17]: 432 An Afrikaans language epic called Building a Nation (Die Bou van 'n Nasie) was made in 1938 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Great Trek.[26] The film tells the Afrikaans version of the history of South Africa from 1652 to 1910 with a focus on the Great Trek.[27]

A number of Afrikaans organisations such as the Afrikaner Broederbond and Afrikaanse Taal en Kultuurvereniging continued to promote the centenary's goals of furthering the Afrikaner cause and entrenching a greater sense of unity and solidarity within the community well into the 20th century.[17]: 432 [28]

Political impact

[edit]The Great Trek was used by Afrikaner nationalists as a core symbol of a common Afrikaans history. It was used to promote the idea of an Afrikaans nation and a narrative that promoted the ideals of the National Party. In 1938, celebrations of the centenary of the Battle of Blood River and the Great Trek mobilised behind an Afrikaans nationalist theses. The narrative of Afrikaner nationalism was a significant reason for the National Party's victory in the 1948 elections. A year later the Voortrekker Monument was completed and opened in Pretoria by the newly elected South African Prime Minister and National Party member Daniel Malan in 1949.

A few years later, "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" ('The Voice of South Africa'), a poem written by Cornelis Jacobus Langenhoven referring to the Great Trek, was chosen to be the words of the pre-1994 South African national anthem. The post-1997 national anthem of South Africa incorporates a section of "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" but it was decided to omit the section in "reference to the Great Trek ('met die kreun van ossewa'), since this was the experience of only one section of our community".[29] When apartheid in South Africa ended and the country transitioned to majority rule, President F. W. de Klerk invoked the measures as a new Great Trek.[30]

In fiction

[edit]Literature

[edit]English

[edit]- H. Rider Haggard, Swallow (1899) and Marie (1912)

- Stuart Cloete, Turning Wheels (1937)

- Helga Moray, Untamed (1950) - a 1955 movie of the same name is based on this book.

- James A. Michener, The Covenant (1980)

- Zakes Mda, The Madonna of Excelsior (2002) ISBN 0312423829

- Robin Binckes, Canvas under the Sky (2011) ISBN 1920143637 - a controversial novel about a promiscuous drug-using Voortrekker set during the Great Trek.[31]

Afrikaans

[edit]- Jeanette Ferreira

- Die son kom aan die seekant op (2007; 'The sun comes up over the sea')[32]

- Geknelde land (English: Afflicted land) (1960)

- Offerland (English: Land of sacrifice) (1963)

- Gelofteland (English: Land of the covenant) (1966)

- Bedoelde land (English: Intended land) (1968)

Dutch

[edit]- C. W. H. Van der Post, Piet Uijs, of lijden en strijd der voortrekkers in Natal, novel, 1918.

Film

[edit]- Untamed (1955), an adventure/love story set in the later part of the trek about an Irish woman seeking a new life in South Africa after the Great Famine. Based on a 1950 novel of the same name by Helga Moray.

- The Fiercest Heart (1961), an adventure/love story about two British soldiers who desert the military and join a group of Boers heading north on the Great Trek.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Laband, John (2005). The Transvaal Rebellion: The First Boer War, 1880–1881. Abingdon: Routledge Books. pp. 10–13. ISBN 978-0582772618.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lloyd, Trevor Owen (1997). The British Empire, 1558–1995. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201–206. ISBN 978-0198731337.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Greaves, Adrian (2013). The Tribe that Washed its Spears: The Zulus at War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 36–55. ISBN 978-1629145136.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c d Arquilla, John (2011). Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits: How Masters of Irregular Warfare Have Shaped Our World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. pp. 130–142. ISBN 978-1566638326.

- ^ a b c Bradley, John; Bradley, Liz; Vidar, Jon; Fine, Victoria (2011). Cape Town: Winelands & the Garden Route. Madison, Wisconsin: Modern Overland. pp. 13–19. ISBN 978-1609871222.

- ^ "The Empty Land Myth". South African History Online. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hunt, John (2005). Campbell, Heather-Ann (ed.). Dutch South Africa: Early Settlers at the Cape, 1652–1708. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 13–35. ISBN 978-1904744955.

- ^ Parthesius, Robert (2010). Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595–1660. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9053565179.

- ^ Lucas, Gavin (2004). An Archaeology of Colonial Identity: Power and Material Culture in the Dwars Valley, South Africa. New York: Springer. pp. 29–33. ISBN 978-0306485381.

- ^ Lambert, David (2009). The Protestant International and the Huguenot Migration to Virginia. New York: Peter Land Publishing. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1433107597.

- ^ a b c Entry: Cape Colony. Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1933. James Louis Garvin, editor.

- ^ a b Mbenga, Bernard; Giliomee, Hermann (2007). New History of South Africa. Cape Town: Tafelberg. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0624043591.

- ^ a b c d e Collins, Robert; Burns, James (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 288–293. ISBN 978-1107628519.

- ^ a b c Newton, A. P.; Benians, E. A., eds. (1963). The Cambridge History of the British Empire. Vol. 8: South Africa, Rhodesia and the Protectorates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 272, 320–322, 490.

- ^ a b Simons, Mary; James, Wilmot Godfrey (1989). The Angry Divide: Social and Economic History of the Western Cape. Claremont: David Philip. pp. 31–35. ISBN 978-0864861160.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Giliomee, Hermann (2003). The Afrikaners: Biography of a People. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. p. 161. ISBN 062403884X.

- ^ Gooch, John (2000). The Boer War: Direction, Experience and Image. Abingdon: Routledge Books. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0714651019.

- ^ Ransford, Oliver (1972). The Great Trek. London: John Murray. p. 42.

- ^ "Johannes Jacobus Janse (Lang Hans) van Rensburg, leader of one of the early Voortrekker treks, is born at the Sundays River". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Bulpin, T. V. "9 - The Voortrekkers". Natal and the Zulu Country. T. V. Bulpin Publications.

- ^ du Toit, André. "(Re)reading the Narratives of Political Violence in South Africa: Indigenous founding myths & frontier violence as discourse" (PDF). p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ Johnston, Harry Hamilton (1910). Britain across the seas: Africa; a history and description of the British Empire in Africa. London: National Society's Depository. p. 111.

- ^ Bulpin, T. V. "11 - The Republic of Natal". Natal and the Zuku Country. T. V. Bulpin Publications.

- ^ a b "Battle of Blood River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ Die Bou van 'n Nasie [Building a Nation] (in Afrikaans). 1938. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "Die Bou van 'n Nasie" (in Afrikaans). IMDb. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "Great Trek Centenary Celebrations commence". South African History Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "The national anthem is owned by everyone". South African Music Rights Organisation. 17 June 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Lyman, Rick (22 December 1993). "South Africa approves new constitution to end white rule". Knight-Ridder Newspapers. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Ritchie, Kevin (11 February 2012). "Mad Boers burn Great Trek bodice ripper". IOL News. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Ferreira, Janette (2007). Die Son Kom Aan die Seekant Op (in Afrikaans). Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau.

Further reading

[edit]- Benyon, John. "The necessity for new perspectives in South African history with particular reference to the Great Trek." Historia Archive 33.2 (1988): 1–10. online[permanent dead link]

- Cloete, Henry. The history of the great Boer trek and the origin of the South African republics (J. Murray, 1899) online.

- Etherington, Norman. "The Great Trek in relation to the Mfecane: a reassessment." South African Historical Journal 25.1 (1991): 3–21.

- Petzold, Jochen. "'Translating' the Great Trek to the twentieth century: re-interpretations of the Afrikaner myth in three South African novels." English in Africa 34.1 (2007): 115–131.

- Routh, C. R. N. "The Great South African Trek." History Today (May 1951) 1#5 pp 7–13 online.

- Von Veh, Karen. "The politics of memory in South African art." de arte 54.1 (2019): 3–24.