Upper German

| Upper German | |

|---|---|

| Oberdeutsch | |

| Geographic distribution | Southern Germany, northern and central Switzerland, Austria, Liechtenstein, Northern Italy (South Tyrol), France (Alsace) |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

Early form | |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | high1286 |

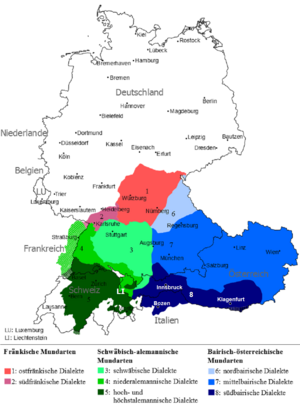

Upper German after 1945 and the expulsions of the Germans. | |

Upper German (German: Oberdeutsch [ˈoːbɐdɔʏtʃ] ) is a family of High German dialects spoken primarily in the southern German-speaking area (Sprachraum).

History

[edit]In the Old High German time, only Alemannic and Bairisch are grouped as Upper German.[4] In the Middle High German time, East Franconian and sometimes South Franconian are added to this. Swabian splits off from Alemannic due to the New High German diphthongisation (neuhochdeutsche Diphthongierung).[5]

Family tree

[edit]Upper German proper comprises the Alemannic and Bavarian dialect groups. Furthermore, the High Franconian dialects, spoken up to the Speyer line isogloss in the north, are often also included in the Upper German dialect group. Whether they should be included as part of Upper German or instead classified as Central German is an open question, as they have traits of both Upper and Central German and are frequently described as a transitional zone. Hence, either scheme can be encountered. Erzgebirgisch, usually lumped in with Upper Saxon on geographical grounds, is closer to East Franconian linguistically, especially the western dialects of Erzgebirgisch.

Roughly

[edit]Upper German is divided roughly in multiple different ways,[6] for example in:[7][8]

- North Upper German (Nordoberdeutsch): East Franconian and South Franconian

- West Upper German (Westoberdeutsch): Swabian and Alemannic

- East Upper German (Ostoberdeutsch): Bavarian (North, Middle and South Bavarian)

or:[9]

- West Upper German: Alemannic (Low and Highest Alemannic, Swabian), East Franconian

- East Upper German: Bavarian (North, Middle and South Bavarian)

- West Upper German: Alemannic in the broad sense (i.e. Alemannic in the strict sense, including Alsatian, and Swabian), South Franconian, East Franconian

- East Upper German: Bavarian (North, Middle and South Bavarian)

or writing dialects (Schriftdialekte, Schreibdialekte) in the Early New High German times:[12]

- West Upper German: South Franconian, Swabian, Alemannic

- East Upper German: Bavarian, East Franconian

In English there is also a grouping into:[13]

- South Upper German: South and Middle Alemannic, South Bavarian, South Middle Bavarian "on the east bank of the Lech" – where the "state of initial consonants is largely that of Old High German"

- North Upper German: North Alemannic, North Bavarian, Middle Bavarian – which "have allegedly weaking many initial fortes"

Attempts to group East Franconian and North Bavarian together as North Upper German are not justified[14] and were not sustainable.[15]

Detailed

[edit]- High Franconian or Upper Franconian (German: Oberfränkisch, sometimes Hochfränkisch), spoken in the Bavarian Franconia region, as well as in the adjacent regions of northern Baden-Württemberg and southern Thuringia

- East Franconian (German: Ostfränkisch, Mainfränkisch, colloquially just Fränkisch)

- Main-Franconian, mainly spoken in Bavarian Franconia, in the adjacent Main-Tauber-Kreis of Baden-Württemberg, as well as in Thuringia south of the Rennsteig ridge in the Thuringian Forest

- Itzgründish (Itzgründisch), spoken in the Itz Valley

- Vogtlandish (Vogtländisch), spoken in Vogtland, Saxony [sometimes; sometimes classified as East Central German separated from Upper Franconian[16]]

- Main-Franconian, mainly spoken in Bavarian Franconia, in the adjacent Main-Tauber-Kreis of Baden-Württemberg, as well as in Thuringia south of the Rennsteig ridge in the Thuringian Forest

- South Franconian (Südfränkisch), spoken in the Heilbronn-Franken region of northern Baden-Württemberg down to the Karlsruhe district

- East Franconian (German: Ostfränkisch, Mainfränkisch, colloquially just Fränkisch)

- Alemannic in the broad sense (German: Alemannisch, Alemannisch-Schwäbisch, or also Gesamtalemannisch[17]), spoken in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, in the Bavarian region of Swabia, in Switzerland, Liechtenstein, the Austrian state of Vorarlberg and in Alsace, France

- Swabian (German: Schwäbisch), spoken mostly in Swabia,[5] and further separated by the sounds in the equivalents of German breit 'broad', groß 'great', Schnee 'snow'

- West Swabian (Westschwäbisch): broat, grauß, Schnai

- Central Swabian (Zentralschwäbisch): broit, grauß, Schnai

- East Swabian (Ostschwäbisch): broit, groaß, Schnäa

- South Swabian (Südschwäbisch): broit/broat, grooß, Schnee

- Alemannic in the strict sense (German: Alemannisch)

- Low Alemannic (Niederalemannisch)

- Alsatian (Elsässisch), spoken in Alsace, now France

- Colonia Tovar German or Alemán Coloniero, spoken in Colonia Tovar, Venezuela

- Basel German (German: Baseldeutsch, Basel German: Baseldytsch)

- High Alemannic (Hochalemannisch)

- Bernese German (German: Berndeutsch, Bernese: Bärndütsch)

- Zurich German (German: Zürichdeutsch, Zurich German: Züritütsch or Züritüütsch)

- Highest Alemannic (Höchstalemannisch)

- Walser German (Walserdeutsch) or Walliser German (Walliserdeutsch), spoken in the Wallis Canton of Switzerland

- Low Alemannic (Niederalemannisch)

- Swabian (German: Schwäbisch), spoken mostly in Swabia,[5] and further separated by the sounds in the equivalents of German breit 'broad', groß 'great', Schnee 'snow'

- Bavarian (or Bavarian-Austrian,[18] Bavarian–Austrian[19]) (German: Bairisch, Bairisch-Österreichisch), spoken in the German state of Bavaria, in Austria, and in South Tyrol, Italy

- Northern Bavarian or North Bavarian (Nordbairisch), spoken mainly in the Bavarian Upper Palatinate region

- Central Bavarian (Mittelbairisch; also Donaubairisch, literally Danube Bavarian[20][21]), spoken mainly in Upper and Lower Bavaria, in Salzburg, Upper and Lower Austria

- Viennese German (Wienerisch), spoken in Vienna and parts of Lower Austria

- Southern Bavarian or South Bavarian (Südbairisch; sometimes also Alpenbairisch, literally Alpine Bavarian[21]), spoken mainly in the Austrian states of Tyrol, Carinthia and Styria, as well as in South Tyrol, Italy

- Gottscheerish or Granish (German: Gottscheerisch, Gottscheerish: Göttscheabarisch, Slovene: kočevarščina), spoken in Gottschee, Slovenia, nearly extinct

- Cimbrian (German: Zimbrisch, Cimbrian: Zimbar, Italian: Italian: lingua cimbra), spoken in the Seven Communities (formerly also in the Thirteen Communities) in Veneto, and around Luserna (Lusern), Trentino, Italy

- Mòcheno language (German: Fersentalerisch, Mòcheno: Bersntoler sproch, Italian: lingua mòchena), spoken in the Mocheni Valley, Trentino in Italy

- Hutterite German (German: Hutterisch), spoken in Canada and the United States

Other ways to group Alemannic include:[22]

- Alemannic in the strict sense besides Swabian:[5][17]

- Upper-Rhine Alemannic[23] or Upper Rhine Alemannic[24] (Oberrheinalemannisch or Oberrhein-Alemannisch): having shifted -b- between vowels to -w- and -g- between vowels to -ch-

- Lake Constance Alemannic[23][24] (Bodenseealemannisch or Bodensee-Alemannisch): having soundings like broat (breit), Goaß (Geiß), Soal (Seil)

- South or High Alemannic (Südalemannisch or Hochalemannisch)

- Alemannic in the strict sense:[25]

- Oberrheinisch (Niederalemannisch)

- separated by the Sundgau-Bodensee-Schranke: Kind/Chind

- Südalemannisch

- Hochalemannisch

- separated by the Schweizerdeutsche nk-Schranke: trinken/trī(n)chen

- Höchstalemannisch

- Alemannic in the strict sense (in the early New High German time):[8]

- Niederalemannisch

- Elsässisch

- östliches Niederalemannisch

- Hochalemannisch

- Westhochalemannisch

- Osthochalemannisch

- Niederalemannisch

- Alemannic in the broad sense including Swabian (in the Middle High German time):[26][27]

- Nordalemannisch or Schwäbisch (between Schwarzwald and Lech; since the 13th century)

- Niederalemannisch or Oberrheinisch (Elsaß, southern Württemberg, Voralberg)

- Hochalemannisch or Südalemannisch (Südbaden and Swiss)

- Alemannic in the broad sense:[28]

- Nordalemannisch

- Schwäbisch

- Niederalemannisch

- Mittelalemannisch = Bodenseealemannisch[29]

- Südalemannisch

- Hochalemannisch

- Höchstalemannisch

- Nordalemannisch

- Alemannic in the broad sense:[30]

- Schwäbisch

- Niederalemannisch

- Hochalemannisch: having shifted k to kχ

- Mittelalemannisch

- Ober- oder Höchstalemannisch: also having shifted k after n to kχ

- Alemannic in the broad sense (with some exemplary differentiations):[31]

- Niederalemannisch

- Schwäbisch

- differentiated by the Early New High German diphthongisation (frühneuhochdeutsche Diphthongierung), and also the verbal uniform plural or Einheitsplural (verbaler Einheitsplural) -et/-e and the lexemes Wiese/Matte (Wiese)

- Oberrheinalemannisch

- Bodenseealemannisch

- differentiated by shift of k (k-Verschiebung)

- Hochalemannisch

- differentiated by nasal loss before fricative (Nasalausfall vor Frikativ), and also the inflection of predicative adjectives

- Höchstalemannisch

- Niederalemannisch

Sometimes the dialect of the Western Lake (Seealemannisch, literally Lake Alemannic) (northern of the Bodensee) is differentiated.[32][33]

Langobardic (Lombardic)

[edit]Based on the fact that Langobardic (German: Langobardisch), extinct around 1000, has undergone the High German consonant shift, it is also often classified as Upper German.[34][35] A competing view is that it is an open question where to place Langobardic inside of Old High German and if it is Old High German at all.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Peter Ernst: Deutsche Sprachgeschichte: Eine Einführung in die diachrone Sprachwissenschaft des Deutschen. 3rd ed., UTB / facultas Verlag, 2021, p. 76 [about Old and early Middle High German]

- ^ a b Heinz Mettke: Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. 8. Aufl., Tübingen, 2000, p. 20ff. [the grammar is about Middle High German, but the dialectal overview more general]

- ^ Thordis Hennings: Einführung in das Mittelhochdeutsche. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2020, p. 5–7 [about Middle High German], having: „Das Oberdeutsche: [..] das Alemannische, Bairische, Südrheinfränkische und Ostfränkische.“

- ^ Stefan Sonderegger: Althochdeutsche Sprache und Literatur: Eine Einführung in das älteste Deutsch: Darstellung und Grammatik. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1974, p. 63ff.

- ^ a b c Frank Janle, Hubert Klausmann: Dialekt und Standardsprache in der Deutschdidaktik: Eine Einführung. Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, Tübingen, 2020, p. 30f. (chapter 3.1.2 Die Gliederung der Dialekte)

- ^ See also:

Frédéric Hartweg, Klaus-Peter Wegera: Frühneuhochdeutsch: Eine Einführung in die deutsche Sprache des Spätmittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Number 33 of Germanistische Arbeitshefte, edited by Gerd Fritz and Franz Hundsnurscher. 2nd ed., Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 2005, p. 30–32, giving different classifications, including:

- A grouping by the Early New High German graphemic appearances (with reference to Werner Besch):

- „Oobd.: Süd-, Mittel-, Nordbairisch, Ostfränkisch,

Wobd.: Südfränkisch, Schwäbisch, Nieder- und Hochalemannisch.“

- „Oobd.: Süd-, Mittel-, Nordbairisch, Ostfränkisch,

- The classification of Oskar Reichmann found in the Frühneuhochdeutsche Wörterbuch (FWB) and together with a map „Deutscher Mundartraum vor 1945“

- „Westoberdeutsch“: „Alemannisch“ („Niederalemannisch“, „Hochalemannisch“), „Schwäbisch“

- „Nordoberdeutsch“ (including „Südfränkisch“)

- „Ostoberdeutsch“: „nördliches Ostoberdeutsch (Nordbairisch)“, „mittleres Ostoberdeutsch (Mittelbairisch)“, „südliches Ostoberdeutsch (Südbairisch)“

- Mentioning Hugo Stopp's approach (1976) of classifying North Bavarian and East Franconian as North Upper German.

- A grouping by the Early New High German graphemic appearances (with reference to Werner Besch):

- ^ Peter von Polenz: Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. 11th ed., edited by Norbert Richard Wolf, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2020, p. 50, having:

- „Nordoberdeutsch“: „Ostfränkisch“, „Südfränkisch“

- „Westoberdeutsch“: „Schwäbisch“, „Alemannisch“

- „Ostoberdeutsch“: „Bairisch-Österreichisch“

- ^ a b Frühneuhochdeutsches Wörterbuch. Herausgegeben von Robert R. Anderson, Ulrich Goebel, Oskar Reichmann. Band 1. Bearbeitet von Oskar Reichmann. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1989, p. 118f., noting that the dialect borders in the Early New High German and later New High German times have not changed much and giving:

- „Nordoberdeutsch“: „Südfränkisch“, „Ostfränkisch“ (including „Nürnbergisch“)

- „Westoberdeutsch“: „Alemannisch“ („Niederalemannisch“, including „Elsässisch“ and „östliches Niederalemannisch“; „Hochalemannisch“, including „Westhochalemannisch“ and „Osthochalemannisch“), „Schwäbisch“

- „Ostoberdeutsch“: „nördliches Ostoberdeutsch, Nordbairisch“, „mittleres Ostoberdeutsch, Mittelbairisch“ (including „Südmittelbairisch“), „südliches Ostoberdeutsch, Südbairisch“ (including „Tirolisch“)

- ^ Markus Steinbach, Ruth Albert, Heiko Girnth, Anette Hohenberger, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Jörg Meibauer, Monika Rothweiler, Monika Schwarz-Friesel: Schnittstellen der germanistischen Linguistik. Verlag J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart/Weimar, 2007, p. 197 (in the chapter Variationslinguistik, subchapter Die Einteilung der deutschen Dialekte, by Heiko Girnth), having:

- „Westoberdeutsch“: „Alemannisch“ („Niederalemannisch“, „Höchstalemannisch“, „Schwäbisch“), „Ostfränkisch“

- „Ostoberdeutsch“: „Bairisch“ („Nordbairisch“, „Mittelbairisch“, „Südbairisch“)

- ^ Gabriele Graefen, Martina Liedke-Göbel: Germanistische Sprachwissenschaft: Deutsch als Erst-, Zweit- oder Fremdsprache. 3rd ed., UTB / Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, Tübingen, 2020, p. 31: „Die Gruppe der westoberdeutschen Dialekte umfasst verschiedene Dialekte des Alemannischen, [...], u.a. Elsässisch und Schwäbisch, sowie das Süd- und Ostfränkische. Dem ostoberdeutschen Dialektraum gehören, die bairischen Dialekte an, [...] Nord-, Mittel- und Südbairisch.“

- ^ Hermann Niebaum, Jürgen Macha: Einführung in die Dialektologie des Deutschen. 2nd ed., 2006 [1st ed. 1999, 3rd 2014], p. 222: „Auch das Oberdeutsche wird in ein westliches und ein östliches Gebiet unterteilt. [...] Das Westobd. zerfällt in Alemannisch, Schwäbisch, Südfränkisch und Ostfränkisch. [...] Der ostobd. oder auch bayrisch-österreichische Sprachraum gliedert sich in Nordbairisch, Mittelbairisch und Südbairisch.“

- ^ Grzegorz M. Chromik: Schreibung und Politik: Untersuchungen zur Graphematik der frühneuhochdeutschen Kanzleisprache des Herzogtums Teschen. Vol. 8 of Studien zum polnisch-deutschen Sprachvergleich. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, Kraków, 2010, p. 20f.: „[...] Einteilung in vier Schriftdialektgebiete [..]: Ostoberdeutsch, Westoberdeutsch, Ostmitteldeutsch und Westmitteldeutsch. [...] Innerhalb des Ostoberdeutschen unterscheidet man bairische und oftfränkische Schriftdialekte, das Westoberdeutsche umfaßt das Südfränkische, Schwäbische und die alemannischen Dialekte, [...]“

- ^ Kurt Gustav Goblirsch: Consonant Strength in Upper German Dialects. (Nowele Supplement Series 10.) John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2012, (originally: Odense University Press, 1994), p. 30

- ^ Metzler Lexikon Sprache. Herausgegeben von Helmut Glück. Verlag J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart/Weimar, 1993, p. 442 s.v. Ostfränkisch.

- ^ Rüdiger Harnisch: Ostfränkisch. In: Sprache und Raum: Ein internationales Handbuch der Sprachvariation. Band 4: Deutsch. Herausgegeben von Joachim Herrgen, Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Unter Mitarbeit von Hanna Fischer und Birgitte Ganswindt. Volume 30.4 of Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science / Manuels de linguistique et des sciences de communication) (HSK). Berlin/Boston, 2019, p. 363ff., here p. 364

- ^ Beat Siebenhaar: Ostmitteldeutsch: Thüringisch und Obersächsisch. In: Sprache und Raum: Ein internationales Handbuch der Sprachvariation. Band 4: Deutsch. Herausgegeben von Joachim Herrgen, Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Unter Mitarbeit von Hanna Fischer und Birgitte Ganswindt. HSK 30.4. Berlin/Boston, 2019, p. 407ff., here p. 407

- ^ a b Peter Auer: Phonologie der Alltagssprache: Eine Untersuchung zur Standard/Dialekt-Variation am Beispiel der Konstanzer Stadtsprache. Vol. 8 of Studia Linguistica Germanica. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, p. 89f.

- ^ Arthur Kirk: An Introduction to the Historical Study of New High German. (Publications of the University of Manchester: Germanic Series: No. II.) Manchester, 1948, p. 30; also Manchester, 1923, p. 11

- ^ Stephen Barbour, Patrick Stevenson: Variation in German: A Critical Approach to German Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 88f. (in the chapter Divisions within Upper German)

- ^ E.g.:

- Heinz Dieter Phl: Österreich (Austria / Autriche). In: Kontaktlinguistik: Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung. 2. Halbband / Contact Linguistics: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research. Volume 2 / Linguistique de contact. Manuel international des recherches contemporaines. Tome 2. Edited by Hans Goebl, Peter H. Nelde, Zdeněk Starý. HSK 12.2. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1997, p. 1809

- Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch: Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte von Rolf Bergmann, Claudine Moulin und Nikolaus Ruge. Unter Mitarbeit von Natalia Filatkina, Falko Klaes und Andrea Rapp. 9th ed., UTB / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2016, p. 203

- ^ a b E.g.

- Gabriele Lunte: The Catholic Bohemian German of Ellis County, Kansas: A Unique Bavarian Dialect. Vol. 316 of European University Studies / Europäische Hochschulschriften / Publications Universitaires Européennes. Peter Lang, 2007, p. 70 & p. 75 [also with translations]

- Maria Prexl: Wortgeographie des mittleren Böhmerwaldes. Nr. 7 of Arbeiten zur sprachlichen Volksforschung in den Sudetenländern. Rudolf M. Rohrer Verlag, Brünn/Leipzig, 1939, p. 3: „[...] gehören dem bairischen Dialekte an. Dieser zerfällt in das Süd- oder Alpenbairische, das Mittel- oder Donaubairische und das Nordbairische (Nordgauische, Oberpfälzische).“

- ^ See also: Tobias Streck: Alemannisch in Deutschland. In: Sprache und Raum: Ein internationales Handbuch der Sprachvariation. Band 4: Deutsch. Herausgegeben von Joachim Herrgen, Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Unter Mitarbeit von Hanna Fischer und Birgitte Ganswindt. HSK 30.4. Berlin/Boston, 2019, p. 206ff., here 209ff. [giving several different classifications]

- ^ a b Javier Caro Reina: Central Catalan and Swabian: A study in the framework of the typology of syllable and word languages. Vol. 422 of Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie, edited by Claudia Polzin-Haumann and Wolfgang Schweickard. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2019, p. 245

- ^ a b Ann-Marie Moser, in: Morphological Variation: Theoretical and empirical perspectives, edited by Antje Dammel and Oliver Schallert. Vol. 207 of Studies in Language Companion Series, edited by Claudia Polzin-Haumann and Wolfgang Schweickard. John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2019, p. 246

- ^ Stefan Sonderegger: Grundzüge deutscher Sprachgeschichte: Diachronie des Sprachsystems: Band I: Einführung – Genealogie – Konstanten. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1979, p. 135 and cp. 198

- ^ Hilkert Weddige: Mittelhochdeutsch: Eine Einführung. 7th ed., Verlag C. H. Beck, München, 2007, p. 8 [having „Hoch- oder Südalemannisch“, „Niederalemannisch“, „Nordalemannisch oder Schwäbisch“ and geography]

- ^ Hermann Paul: Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Von Hugo Moser und Ingeborg Schröbler. 20th ed., Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 1969, p. 8, 127

- ^ Peter Wiesinger: Die Einteilung der deutschen Dialekte. In: Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Herausgegeben von Werner Besch, Ulrich Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke, Herbert Ernst Wiegand. Zweiter Halbband. Volume 1.2 of Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (HSK). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1983, p. 807ff., here p. 829–836

- ^ Peter Wiesinger: Strukturelle historische Dialektologie des Deutschen: Strukturhistorische und strukturgeographische Studien zur Vokalentwicklung deutscher Dialekte. Herausgegeben von Franz Patocka. Vol. 234–236 of Germanistische Linguistik, edited by the Forschungszentrum Deutscher Sprachatlas. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim / Zürich / New York, 2017, p. 117f. (inside of: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der historischen Dialektologie am Beispiel der Lautentwicklung des Mittelalemannischen und südwestlichen Schwäbischen) [equating „Mittelalemannisch oder Bodenseealemannisch“ northern of the „als wichtigste alemannische Süd-Nordscheide betrachtete Sundgau-Bodenseeschranke“]

- ^ Karl Meisen: Altdeutsche Grammatik: I: Lautlehre. J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart, 1961, p. 9f.

- ^ Raffaela Baechler: Absolute Komplexität in der Nominalflexion: Althochdeutsch, Mittelhochdeutsch, Alemannisch und deutsche Standardsprache. Vol. 2 of Morphological Investigations. Language Science Press, Berlin, 2017, p. 43

- ^ Peter Auer: A Case of Convergence and its Interpretation: MHG î and û in the City Dialect of Constance. In: Variation and Convergence: Studies in Social Dialectology. Edited by Peter Auer and Aldo di Luzio. Vol. 4 of Soziolinguistik und Sprachkontakt / Sociolinguistics and Language Contact. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1988, p. 43ff., here 65 [has the English: "the dialect of the Western Lake (Seealemannisch)"]

- ^ Erich Seidelmann: Der Bodenseeraum und die Binnengliederung des Alemannischen. In: Alemannisch im Sprachvergleich. Beiträge zur 14. Arbeitstagung für alemannische Dialektologie in Männedorf (Zürich) vom 16.–18.9.2002. Herausgegeben von Elvira Glaser, Peter Ott, Rudolf Schwarzenbach unter Mitarbeit von Natascha Frey. Series: ZDL-Beiheft 129 [ZDL = Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik]. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004, p. 481–483

- ^ Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte. Begründet von Wilhelm Braune, fortgeführt von Karl Helm, herausgegeben von Helmut de Boor. A. Hauptreihe. Nr. 10. Kurze deutsche Grammatik. Auf Grund der fünfbändigen deutschen Grammatik von Hermann Paul eingerichtet von Heinrich Stolte. 3. Aufl., Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 1962, p. 35f., having:

- „Bairisch“ (also in Austria and Egerland): „Nordbairisch“ (or „Oberpfälzisch“), „Mittelbairisch“, „Südbairisch“

- „Alemannisch“: „Schwäbisch“, „Niederalemannisch“, „Hochalemannisch“

- nowdays also: „Südfränkisch“, „Ostfränkisch“, „Südthüringisch“: in Old High German times also: „Langobardisch“

- ^ Older editions of: Geschichte der deutschen Sprache, by Peter von Polenz, originally by Hans Sperber.

- Geschichte der deutschen Sprache von Dr. Hans Sperber neubearbeitet von Dr. Peter von Polenz. 6th ed., Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin, 1968, p. 25

- Geschichte der deutschen Sprache von Dr. Peter von Polenz. Originally von Hans Sperber. 7th. ed., Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1970, p. 31

- Geschichte der deutschen Sprache von Peter von Polenz. Originally von Hans Sperber. 9th. ed., Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 1978, p. 31

- Note: 10th ed. (Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 2009) and 11th ed. (Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2020) were edited by Norbert Richard Wolf.

- ^ Sprachgeschichte: Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und ihrer Erforschung. Herausgegeben von Werner Besch, Anne Betten, Oskar Reichmann, Stefan Sonderegger. 2. Teilband. 2nd ed. Volume 2.2 of Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science / Manuels de linguistique et des sciences de communication) (HSK). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 2000, p. 1151