Waterford

Waterford

Port Láirge | |

|---|---|

City | |

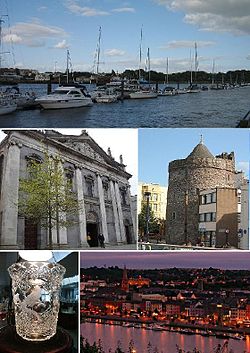

From top, left to right: Waterford Marina, Holy Trinity Cathedral, Reginald's Tower, a piece of Waterford Crystal, Waterford City by night | |

| Nickname: The Déise | |

| Motto(s): Latin: Urbs Intacta Manet Waterfordia "Waterford remains the untaken city" | |

| Coordinates: 52°15′24″N 7°7′45″W / 52.25667°N 7.12917°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| Region | Southern (South-East) |

| County | Waterford |

| Founded | 914 AD |

| City Rights | 1215 AD |

| Government | |

| • Local Authority | Waterford City and County Council |

| • Mayor | Damien Geoghegan (FG) |

| • Local Electoral Areas |

|

| • Dáil constituency | Waterford |

| • European Parliament | South |

| Area | |

| • City | 50.4 km2 (19.5 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • City | 60,079 |

| • Rank | 5th |

| • Density | 1,191.7/km2 (3,086/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 82,963 |

| Demonym(s) | Waterfordian, Déisean |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode Routing Key | X91 |

| Telephone Area Code | 051(+353 51) |

| Vehicle Index Mark Code | W |

| Website | www |

Waterford[a] (Irish: Port Láirge [pˠɔɾˠt̪ˠ ˈl̪ˠaːɾʲ(ə)ɟə]) is a city in County Waterford in the south-east of Ireland. It is located within the province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford Harbour. It is the oldest[2][3] and the fifth most populous city in the Republic of Ireland. It is the ninth most populous settlement on the island of Ireland. According to the 2022 census, 60,079 people live in the city,[1] with a wider metropolitan population of 82,963.

Historically the site of a Viking settlement, Waterford's medieval defensive walls and fortifications include the 13th or 14th century Reginald's Tower. The medieval city was attacked several times, and earned the motto Urbs Intacta Manet ('The Untaken City'), after repelling one such 15th century siege. Waterford is known for its former glassmaking industry, including at the Waterford Crystal factory, with decorative glass being manufactured in the city from 1783 until early 2009 when the factory closed following the receivership of Waterford Wedgwood plc. The Waterford Crystal visitor centre was opened, in the city's Viking Quarter, in 2010 and resumed production under new ownership. As of the 21st century, Waterford is the county town of County Waterford and the local government authority is Waterford City and County Council.

History

[edit]

The name 'Waterford' comes from Old Norse Veðrafjǫrðr 'ram (wether) fjord'. The Irish name is Port Láirge, meaning "Lárag's port".[4]

Viking raiders first established a settlement near Waterford in 853. It and all the other longphorts were vacated c. 902, the Vikings having been driven out by the native Irish. The Vikings re-established themselves in Ireland at Waterford in 914, led at first by Ottir Iarla (Jarl Ottar) until 917, and after that by Ragnall ua Ímair and the Uí Ímair dynasty, and built what would be Ireland's first city. Among the most prominent rulers of Waterford was Ivar of Waterford.

In 1167, Diarmait Mac Murchada, the deposed King of Leinster, failed in an attempt to take Waterford. He returned in 1170 with Cambro-Norman mercenaries under Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (known as Strongbow); together they besieged and took the city after a desperate defence. In furtherance of the Norman invasion of Ireland, King Henry II of England landed at Waterford in 1171. Waterford and then Dublin were declared royal cities, with Dublin also declared the capital of Ireland.

Reginald's Tower, built after the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland on the site of an earlier fortification and retaining its Viking name, was one of the first in Ireland to use mortar in its construction.

Throughout the medieval period, Waterford was Ireland's second city after Dublin. In the 15th century, Waterford repelled sieges by two pretenders to the English throne: Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck. As a result, King Henry VII gave the city its motto: Urbs Intacta Manet Waterfordia ("Waterford remains an untouched city").[3]

After the Protestant Reformation, Waterford remained a Catholic city and participated in the confederation of Kilkenny – an independent Catholic government from 1642 to 1649. This was ended abruptly by Oliver Cromwell, who brought the country back under English rule; his son-in-law Henry Ireton finally took Waterford in 1650 after a two major sieges.[5][6] In 1690, during the Williamite War, the Jacobite Irish Army was forced to surrender Waterford in the wake of the Battle of the Boyne.

The 18th century was a period of huge prosperity for Waterford. Many of the city's architecturally notable buildings appeared during this time. A permanent military presence was established in the city with the completion of the Cavalry Barracks at the end of the 18th century.[7]

In the early 19th century, Waterford City was deemed vulnerable and the British government erected three Martello towers on the Hook Peninsula to reinforce the existing Fort at Duncannon. During the 19th century, industries such as glass making and ship building thrived in the city.

The city was represented in the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1891 to 1918 by John Redmond MP, leader (from January 1900) of the Irish Parliamentary Party. Redmond, then leader of the pro-Parnell faction of the party, defeated David Sheehy in 1891.[citation needed]

In July 1922, Waterford was the scene of fighting between Irish Free State and Irish Republican troops during the Irish Civil War.

References in Annals of Inisfallen

[edit]See Annals of Inisfallen (AI)

- AI926.2 The fleet of Port Láirge [came] over land, and they settled on Loch Gair.

- AI927.2 A slaughter of the foreigners of Port Láirge [was inflicted] at Cell Mo-Chellóc by the men of Mumu and by the foreigners of Luimnech.

- AI984.2 A great naval expedition(?) by the sons of Aralt to Port Láirge, and they and the son of Cennétig exchanged hostages there as a guarantee of both together providing a hosting to attack Áth Cliath. The men of Mumu assembled and proceeded to Mairg Laigen, and the foreigners overcame the Uí Cheinnselaig and went by sea; and the men of Mumu, moreover, devastated Osraige in the same year, and its churches, and the churches of Laigin, and the fortifications of both were laid waste, and Gilla Pátraic, son of Donnchadh, was released.

- AI1018.5 Death of Ragnall son of Ímar, king of Port Láirge.

- AI1031.9 Cell Dara and Port Láirge were burned.

Politics

[edit]Local government

[edit]Following the Local Government Reform Act 2014, Waterford City and County Council is the local government authority for the city and county. The authority came into operation on 1 June 2014. Prior to this the city had its own local council, Waterford City Council. The new council is the result of a merger of Waterford City Council and Waterford County Council. The council has 32 representatives (councillors) who are elected from six local electoral areas. The city itself forms three of the electoral areas – which when combined form the Metropolitan District of Waterford City – and returns a total of 18 councillors to Waterford City and County Council.[8] The office of the Mayor of Waterford was established in 1377. A mayor is elected by the councillors from the three electoral areas of the Metropolitan District of Waterford every year, and there is no limit to the number of terms an individual may serve. Mary O'Halloran, who was mayor from 2007 to 2008, was the first woman to hold the post.

National politics

[edit]For the elections to Dáil Éireann, the city is part of the 4-seat constituency of Waterford, which includes the city and county of Waterford.[9] For elections to the European Parliament, the county is part of the South constituency.[10]

Geography

[edit]

Harbour and port

[edit]The city is situated at the head of Waterford Harbour (Loch Dá Chaoch or Cuan Phort Láirge).[3] The River Suir, which flows through Waterford City, has provided a basis for the city's long maritime history. The place downriver from Waterford where the Nore and the Barrow join the River Suir is known in Irish as Cumar na dTrí Uisce ("The confluence of the three waters"). Waterford Port has been one of Ireland's major ports for over a millennium. In the 19th century, shipbuilding was a major industry. The owners of the Neptune Shipyard, the Malcomson family, built and operated the largest fleet of iron steamers in the world between the mid-1850s and the late 1860s, including five trans-Atlantic passenger liners.[4]

Climate

[edit]The climate of Waterford is, like the rest of Ireland, classified as a maritime temperate climate (Cfb) according to the Köppen climate classification system. It is mild and changeable with abundant rainfall and a lack of temperature extremes. The counties in the Waterford area are often referred to as the 'Sunny Southeast'. The warmest months of the year are June, July and August with average daytime temperatures of around 17 – 22 degrees. Rainfall is evenly distributed year-round; however, the period from late October to late January is considerably wetter and duller than the rest of the year.

| Climate data for Waterford (Tycor), elevation: 49 m or 161 ft, 1989–2019 normals, sunshine 1981-2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.4 (58.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 103.2 (4.06) |

72.9 (2.87) |

74.8 (2.94) |

71.8 (2.83) |

63.8 (2.51) |

71.6 (2.82) |

62.4 (2.46) |

78.5 (3.09) |

79.2 (3.12) |

116.3 (4.58) |

108.9 (4.29) |

108.6 (4.28) |

1,012 (39.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 14 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 13 | 16 | 137 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.3 | 75.7 | 114.1 | 173.9 | 214.9 | 189.9 | 199.5 | 191.1 | 146.1 | 105.5 | 73.3 | 55.2 | 1,599.5 |

| Source 1: Met Éireann[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[12] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]With a 2022 population of 60,079[1] and a metropolitan area population of 82,963,[13] Waterford is the fifth most populous city in the State and the 32nd most populous area of local government.[14]

The population of Waterford grew from 1,555 in 1653 to around 28,000 in the early 19th century, declining to just over 20,000 at the end of the 19th, then rising steadily to over 40,000 during the 20th century.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

Culture

[edit]

Arts

[edit]Theatre companies in Waterford include the Red Kettle, Spraoi and Waterford Youth Arts companies. Red Kettle is a professional theatre company, founded by Waterford playwright Jim Nolan,[21] that regularly performs in Garter Lane Theatre. Spraoi is a street theatre company based in Waterford.[22] It produces the Spraoi festival and has participated regularly in the Waterford and Dublin St. Patrick's day parades. In January 2005 the company staged "Awakening", a production which marked the opening of the Cork 2005 European Capital of Culture program. Waterford Youth Arts (WYA),[23] formerly known as Waterford Youth Drama, was established in August 1985. The Theatre Royal Waterford dates back to 1785.

There are four public libraries in the city, all operated by Waterford City and County Council: Central Library, in Lady Lane; Ardkeen Library, in the Ardkeen shopping centre on the Dunmore Road; Carrickphierish Library in Gracedieu,[24] and Brown's Road Library, on Paddy Brown's Road. Waterford Council operates eight further library branches through the county.[citation needed]

Central Library, or Waterford City Library, opened in 1905. It was the first of many Irish libraries funded by businessman Andrew Carnegie and renovated in 2004 for its centenary. The library is built over Lady's Gate, part of the medieval city walls of the city.

Waterford Film For All (WFFA)[25] is a non-profit film society, operating primarily from the Waterford Institute of Technology (WIT) campus, whose aim is to offer an alternative to the cineplex experience in Waterford.[citation needed]

The Waterford Collection of Art, formerly known as the Waterford Municipal Art Collection, is one of the oldest municipal collections of art in Ireland. Originally founded as the Waterford Art Museum in 1939, the collection now comprises over 500 works of art including works by: Paul Henry, Jack B. Yeats, Mainie Jellett, Louis Le Brocquy, Letitia Hamilton, Dermod O’Brien, Evie Hone, Mary Swanzy, Charles Lamb, Hilda Roberts, Seán Keating, and George Russell (aka. AE).[citation needed]

Greyfriars Church, a disused Methodist church, was purchased by Waterford Corporation in 1988 and refurbished into a museum and gallery.[26][27]

Events

[edit]

- The Waterford Film Festival was established in 2007,[28] celebrating its tenth year in 2016.[29]

- Waterford Music Fest, launched in 2011, is an outdoor, one-day music event which takes place in the city during the summer. In 2011, Waterford Music Fest was headlined by 50 Cent, Flo Rida and G-Unit and was attended by over 10,000 people.[30]

- Spraoi festival, (pronounced 'Spree')[22] organised by the Spraoi Theatre Company, is a street art festival which takes place in the city centre on the August Bank Holiday Weekend. Previous events have attracted audiences in excess of 80,000 people to the city.

- Waterford International Festival of Light Opera[31] is an annual event that has been held in the Theatre Royal since 1959. Also known as the Waterford International Festival of Music, it takes place in November.[32]

- Waterford hosted the Tall Ships Festival in 2005 and 2011.[33] The 2005 festival attracted in the region of 450,000 people to the city.[citation needed]

- St. Patrick's Day parade takes place annually on 17 March.[citation needed]

- Arts festivals which take place in the city include the Imagine Arts Festival[34] in October and The Fringe Arts Festival in September.

- Waterford Winterval an annual Christmas festival held in the city centre.[35]

- Waterford Walls is an event celebrating street art annually each August since 2014. Street artists both domestic and international are invited to the city to practise and display their craft.[36][37]

Public buildings

[edit]- Waterford Museum of Treasures, forming the hub of the Viking Triangle, previously housed in the Granary on Merchant's Quay, is now accommodated in two museums on the Mall. The first is housed in the 19th-century Bishop's Palace, on the Mall, which holds items from 1700 to 1970. This was opened in June 2011. The second museum is located next to Bishop's Palace displaying the Medieval history of the city as well as the Chorister's Hall.[38]

- Reginald's Tower, the oldest urban civic building in the country and the oldest monument to retain its Viking name, is situated on the Quays/The Mall, in Waterford. It has performed numerous functions over the years and today is a civic museum.

- A museum at Mount Sion (Barrack Street) is dedicated to the story of Brother Edmund Ignatius Rice and the history of the Christian Brothers and Presentation Brothers. Along with the museum, there is a café and a new chapel. The new museum was designed by Janvs Design[39]

- Waterford Gallery of Art, the home of the Waterford Art Collection, is located at 31-32 O’Connell Street. This former bank building was built in 1845 and now serves as a facility comprising galleries, outreach spaces, offices, and meeting and workshop rooms. The building was designed by the Waterford-born architect Thomas Jackson (1807 - 1890). Architecturally, this classical style bank building retains many of its original features and has fine cut-stone detailing throughout, including at the main entrance, stairs and first-floor fireplace.[citation needed]

- The Theatre Royal[40] on The Mall, was built in 1876, as part of a remodelled section of City Hall. It is a U-shaped, Victorian theatre, seating about 600 people.

- Garter Lane Arts Centre[41] is housed in two conserved 18th-century buildings on O'Connell Street. Garter Lane Gallery, the 18th-century townhouse of Samuel Barker contains the gallery and the Bausch & Lomb Dance Studio, and Garter Lane Theatre is based in the Quaker Meeting House, built in 1792. The theatre was renovated and restored in 2006 and now contains a 164-seat auditorium.

- St. John's College, Waterford was a Catholic seminary founded in 1807 for the diocese, in the 1830s the college established a mission to Newfoundland in Canada. It closed as a seminary in 1999 and in 2007 much of its building and lands were sold to the Respond! Housing Association.[42]

Religion

[edit]Christian churches in Waterford include the Catholic Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity, the former Franciscan friary of French Church, St Saviour's (Dominican) Church and Priory on Bridge Street,[43] and St Patrick's Catholic Church on Jenkin's Lane, which is one of the earliest surviving post-Reformation churches in Ireland.[44] Church of Ireland places of worship include Christ Church Cathedral[45] and Saint Olave's Church on Peter Street (a Medieval church). Methodist churches include St Patrick’s Methodist Church[46] and Waterford Methodist Church.[citation needed]

Other Christian denominations include Waterford Baptist Church,[47] Anchor Baptist Church,[48] the Waterford Quaker Meeting House (Newtown Road),[49] and the Russian Orthodox Parish of St Patrick.[citation needed]

Media

[edit]RTÉs southeastern studio is in the city.

Waterford Local Radio (WLR FM) is available on 94.8FM on the Coast, 95.1FM in the County and on 97.5FM in Waterford City. WLR FM is Waterford's local radio station. Beat 102 103 is a regional youth radio station broadcasting across the South East of Ireland, it is based in Ardkeen, along with sister station WLR FM.

The Waterford News & Star is based on Gladstone Street in Waterford City. It covers Waterford city and county. It is now published in tabloid format.

The Munster Express has its office on the Quay in Waterford City and covers stories from across the city and county. It switched to tabloid format in 2011.

Local free sheets include the Waterford Mail (which comes out on Thursdays and has an office on O'Connell Street) and Waterford Today (an advertising-supported free newspaper which is published on Wednesdays and has an office on Mayors Walk).[citation needed]

Places of interest

[edit]

The city of Waterford consists of several cultural quarters, the oldest of which is known as Viking Triangle. This is the part of the city surrounded by the original tenth-century fortifications and is triangular in shape, with its apex at Reginald's Tower. Though once the site of a thriving Viking settlement, the city centre subsequently shifted to the west, and it is now a quieter area with narrow streets, medieval architecture, and civic spaces.[citation needed]

In the 15th century, the city was enlarged with the building of an outer wall on the west side. Today Waterford retains more of its city walls than any other city in Ireland with the exception of Derry, whose walls were built much later. Tours of Waterford's city walls are conducted daily.[citation needed]

The Quay, once termed by historian Mark Girouard as 'the noblest quay in Europe', is a mile long from Grattan Quay to Adelphi Quay, though Adelphi Quay is now a residential area. Near Reginald's Tower is the William Vincent Wallace Plaza, a monument and amenity built around the time of the millennium that commemorates the Waterford-born composer.[citation needed]

John Roberts Square is a pedestrianised area that is one of the focal points of Waterford's modern-day commercial centre.[citation needed] It was named after the Waterford architect, John Roberts, and was formed from the junction of Barronstrand Street, Broad Street and George's Street. It is often referred to locally as Red Square, due to the red paving that was used when the area was first pedestrianised. A short distance to the east of John Roberts Square is Arundel Square, which the City Square shopping centre opens onto.

Ballybricken, in the west, just outside the city walls, is thought to have been Waterford's Irishtown,[citation needed] a type of settlement that often formed outside Irish cities to house the Vikings and Irish that had been expelled during the Norman invasion of Ireland. Modern street names in the area reflect the fact that the area was where inhabitants of the medieval city practised archery.[50][51] Ballybricken is an inner-city neighbourhood centred around Ballybricken hill, which was a large, open market-square. Today it has been converted into a green, civic space, but the Bull Post, where livestock was once bought and sold, still stands as a remnant of the hill's past.[citation needed]

The Mall is a Georgian thoroughfare, built by the Wide Streets Commission to extend the city southwards. It contains some of the city's finest Georgian architecture.[citation needed] The People's Park, Waterford's largest park, is located nearby.

Once a historic market area, the city's Apple Market district is known for its nightlife culture and includes a number of bars, restaurants and nightclubs.[citation needed] Investment in the mid-2010s saw a portion of the area pedestrianised and the installation of a large outdoor roofing section.[52]

Ferrybank, in County Waterford, is Waterford's only suburb north of the river. It contains a village centre of its own.

In April 2003, a site combining a fifth-century Iron Age and ninth-century Viking settlement was discovered at Woodstown near the city, which appears to have been a Viking town that predates all such settlements in Ireland.[53]

Waterford is known for Waterford Crystal, a legacy of the city's former glass-making industry. Glass, or crystal, was manufactured in the city from 1783 until early 2009 when the factory there was shut down after the receivership of Waterford Wedgwood plc.[54] A new Waterford Crystal visitor centre in the Viking Quarter, under new owners, opened in June 2010, after the intervention of Waterford City Council and Waterford Chamber of Commerce, and resumed production.[55]

Waterford's oldest public house (pub) is located outside the old 'Viking Triangle'. T & H Doolan's, of 31/32 George's Street, has acted as a licensed premises since the 18th century but the premises is believed to be closer to five hundred years in age.[citation needed] The pub's structure includes one of the original city walls, almost 1,000 years old, which can be viewed in the lounge area of the building.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]Waterford is the main city of Ireland's South-East Region. Historically Waterford was an important trading port which brought much prosperity to the city throughout the city's eventful history. Throughout its history, Waterford Crystal provided employment to thousands in the city and surrounding areas.

Waterford Port is Ireland's closest deep-water port to mainland Europe, handling approximately 12% of Ireland's external trade by value.[56] Waterford's most famous export, Waterford Crystal, was manufactured in the city from 1783 to 2009 and again from 2010 to the present day. Places, where Waterford Crystal can be seen, include New York City, where Waterford Crystal made the 2,668 crystals for the New Year's Eve Ball that is dropped each year in Times Square; Westminster Abbey; Windsor Castle; and the Kennedy Center (Washington, DC).[57][58]

Agriculture played an important part in Waterford's economic history. Kilmeadan, about 5 km from the city, was home to a very successful co-operative. The farmers of the area benefited from the sale of their produce (mostly butter and milk) to the co-op. In 1964, all of the co-ops in Waterford amalgamated to become Waterford Co-op. This led to the construction of a cheese factory on a greenfield site opposite the general store, and Kilmeadan cheese was to become one of the most recognised and successful Cheddar brands in the world, winning gold and bronze medals in the World Cheese Awards in London in 2005.[citation needed]

The Irish economic recession from 2008 onwards has had a major negative impact on Waterford's economy. A number of multinational companies have closed, including Waterford Crystal (which subsequently reopened) and Talk Talk, which has led to a high level of unemployment. Until 2013 the hedge fund office of the Citibank resided here.[59]

Waterford Co-op and Avonmore Co-op have merged to form Glanbia plc.[60]

Transport

[edit]The M9 motorway, which was completed on 9 September 2010, connects the city to Dublin.[61] The N24 road connects the city to Limerick city. The N25 road connects the city to Cork city. The route traverses the River Suir via the River Suir Bridge. This cable-stayed bridge is the longest single bridge span in Ireland at 230m. The route continues eastwards to Rosslare Harbour.

Waterford railway station is the only railway station in the county of Waterford. It is operated by Iarnród Éireann and provides 8 daily return services to Dublin and a Monday–Saturday Intercity service to Limerick Junction via Clonmel with onward connections to Limerick, Ennis, Athenry, Galway, Cork, Killarney, and Tralee.[62][63] The line between Waterford and Rosslare Harbour ceased passenger services in 2010 and was replaced by Bus Éireann route 370. The station is directly connected to Waterford Port (Belview). A freight yard is located at the Dublin/Limerick end of the station, served by freight traffic such as cargo freight and timber which travel to and from Dublin Port and Ballina. In November 2016 it was revealed the Waterford could lose its connection to Limerick Junction by 2018 with the closure of the Limerick Junction Waterford line by CIE/IE to save money as the line is low demand.[64] On 29 May 2018 the contract held by DFDS for a freight service from Ballina to Belview Port expired and was not renewed.[65] In 2021 a new Ballina to Waterford (Belview) by Iarnród Éireann and XPO Logistics, (this is in addition to the wood pulp service from Ballina and Westport).[66]

Bus Éireann, JJ Kavanagh and Sons, Dublin Coach, and Wexford Bus provide bus services around the city centre and to other towns and cities in Ireland.[67][68] A daily coach service to England via South Wales and terminating at Victoria Coach Station, London is operated by Eurolines.[69] All regional bus services depart from Waterford Bus Station on the quay, and city centre services run throughout the city. Planning for bus lanes in the city centre are at an early stage and bus lanes will be on Parnell Street, Manor Street, The Mall, and the South Quays. A bus lane will be in each direction. On street parking will be removed from Parnell Street to facilitate the lanes. This is part of the city centre green plan.[70]

The Waterford Greenway is Ireland's longest greenway, and connects the city with Mount Congreve, Kilmeaden, Kilmacthomas, and Dungarvan.[71]

Waterford Airport is located 9 km outside the city centre. Waterford was the "starting point" of one of the largest airlines by scheduled international passengers, Ryanair, which operated its first flight on a 14-seat Embraer Bandeirante turboprop aircraft, between Waterford and Gatwick Airport.[72]

Education

[edit]The city is served by 21 primary schools,[73] nine secondary schools,[74] a further education college and a university.

Secondary schools

[edit]There are several secondary schools in the area. Mount Sion Secondary and Primary School, located at Barrack Street, were founded by Edmund Ignatius Rice.[75] Newtown School is a Quaker co-educational boarding school. Waterpark College was established in 1892 on the banks of the River Suir as Waterford's first classical school. It still provides a secondary education and has recently become a co-educational school.[citation needed] De La Salle College, a secondary school with 1,200 students and over 90 staff, is the biggest all-boys school in the county. Founded by the De La Salle brothers in 1892, it is a Catholic school for boys.[76] Today its large staff is made up of a mixture of Brothers and lay teachers. St. Angela's Secondary School is a Catholic all-girls school with approximately 970 students enrolled as of 2023.[77]

Further education

[edit]Waterford College of Further Education previously called the Central Technical Institute (CTI), is a Post Leaving Certificate institute located on Parnell Street, Waterford city. It was founded in 1906 and thus celebrated its centenary in 2005.[78]

University

[edit]South East Technological University - the Waterford campus of the university is located in the city. This was established in 2022 from a merger of Waterford Institute of Technology and Institute of Technology, Carlow.[79][80]

Sport

[edit]

Waterford Boat Club is the oldest active sports club in Waterford, established in 1878.[81] Located on Scotch Quay, the club competes in the Irish Rowing Championships.[82] In 2009, several Waterford rowers were selected to row for Ireland.

There are three athletics clubs: West Waterford AC, Waterford Athletic Club and Ferrybank Athletic Club. The Waterford Viking Marathon is held in June.[83] St. Anne's Waterford Lawn Tennis Club, established in 1954, is the result of the amalgamation of Waterford Lawn Tennis Club and St. Anne's Lawn Tennis Club. It has nine courts to cater for social and competitive players in all age groups.[84]

Waterford is home to several association football clubs, including Waterford FC, Benfica W.S.C. and Johnville F.C. Waterford F.C. is a member of the League of Ireland. Notable Waterford footballers include Davy Walsh, Paddy Coad, Jim Beglin, Alfie Hale, Eddie Nolan, John O'Shea and Daryl Murphy. John Delaney, former chief executive of the Football Association of Ireland, is originally from Waterford.

There are two rugby union clubs in Waterford City: Waterford City R.F.C.[85] and Waterpark R.F.C.[86]

Other team sports include Gaelic Athletic Association with clubs such as Mount Sion GAA, Erin's Own GAA, De La Salle GAA, Roanmore GAA, Ferrybank GAA and Ballygunner GAA; cricket is represented by Waterford District Cricket Club, who are based in Carriganore [87] and compete in the Munster Cricket Union; there are two inline hockey clubs, Waterford Shadows HC and Waterford Vikings, both of which compete in the Irish Inline Hockey League; and American football is played by Waterford Wolves, based at the Waterford Regional Sports Centre, and is the only American football club in Waterford.

Notable people

[edit]- Marie Bonaparte-Wyse (1831–1902), French poet[citation needed]

- Brendan Bowyer (1938–2020) showband singer[88]

- Charles Clagget (c.1740–c.1820), composer and inventor[89]

- Frances Emilia Crofton (1822–1910), an artist born in Waterford[citation needed]

- Val Doonican (1927–2015), singer and TV presenter[90]

- Seán Dunne (1956–1995), poet[91]

- Richard Harry Graves (1897–1971), Irish-born Australian writer[citation needed]

- Megan Nolan (born 1990), Irish journalist and author[92]

- Gilbert O'Sullivan (born 1946), singer-songwriter[93]

- Mario Rosenstock (born 1971), comedian and musician[citation needed]

- Louis Stewart (guitarist) (1944–2016), jazz guitarist[94]

- Luke Wadding (1588–1657), Franciscan friar, author and historian[95]

- William Vincent Wallace (1812–1865), composer[96]

Politics

- William Hobson (1792–1842), Irish-born New Zealand politician and writer[97]

- Thomas Meagher (1796–1874), politician and businessman[98]

- Thomas Francis Meagher (1823–1867), politician and soldier[99]

- Richard Mulcahy (1886–1971), soldier and politician[100]

- Thomas Wyse (1791–1862), politician and diplomat[101]

Sport

- Jim Beglin (born 1963), association footballer[102]

- John Keane (1917–1975), hurler[citation needed]

- Sean Kelly (born 1956), cyclist[citation needed]

- John O'Shea (born 1981), association footballer[103]

- Paul Flynn (born 1974), hurler[citation needed]

- Craig Breen (1990–2023), rally driver[citation needed]

Military

- John Condon (c 1896–1915), soldier[citation needed]

- Edmund Fowler (1861–1926), soldier, recipient of the Victoria Cross[citation needed]

- Patrick Mahoney (1827–1857), soldier, recipient of the Victoria Cross[citation needed]

Other

- Marguerite Moore (1849–1933), orator and activist[104]

- Harry Power (1819–1891), Australian bushranger[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Blaa – A doughy, white bread roll particular to Waterford City.

- John's River – A river that runs through Waterford City.

- Little Island – An island within Waterford City.

- The Three Sisters: The River Barrow, River Nore and River Suir

- List of twin towns and sister cities in the Republic of Ireland

Notes

[edit]- ^ From Old Norse Veðrafjǫrðr [ˈweðrɑˌfjɒrðr̩], meaning "ram (wether) fjord".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Census 2022 Profile 1 - Population Distribution and Movement". Central Statistics Office. 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "About Waterford City". waterfordchamber.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Waterford City Council : About Our City Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Waterfordcity.ie. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ a b Discover Waterford, by Eamon McEneaney (2001). (ISBN 0-86278-656-8)

- ^ A New History of Cromwell's Irish Campaign, by Philip McKeiver (2007). (ISBN 978-0-9554663-0-4)

- ^ Discover Waterford, by Eamon McEneaney (2001). (ISBN 0-86278-656-8)

- ^ "Heritage Walk map" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ City and County of Waterford Local Electoral Areas and Municipal Districts Order 2018 (S.I. No. 635 of 2018). Signed on 19 December 2018. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 12 September 2020.

- ^ Electoral (Amendment) (Dáil Constituencies) Act 2017, Schedule (No. 39 of 2017, Schedule). Enacted on 23 December 2017. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 8 August 2021.

- ^ European Parliament Elections (Amendment) Act 2019, s. 7: Substitution of Third Schedule to Principal Act (No. 7 of 2019, s. 7). Enacted on 12 March 2019. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Tycor 1989-2019 Averages, Sunshine for Rosslare 1981-2010 (closest historic station)". Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "ECA&D, Tycor". Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Census 2016 Summary Results - Part 1" (PDF). Cso.ie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Corry, Eoghan (2005). The GAA Book of Lists. Hodder Headline Ireland. pp. 186–191.

- ^ For 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years, Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy 14 March 1865.

- ^ "Server Error 404 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Histpop.org". Histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Home". Nisranew.nisraa.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- ^ Jim Nolan – Current Member | Aosdana Archived 9 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Aosdana.artscouncil.ie. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Home – Spraoi". Spraoi. Archived from the original on 13 January 2007.

- ^ "Waterford Youth Arts in Waterford, Ireland". waterfordyoutharts.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006.

- ^ Express, Munster (16 March 2018). "Community Campus Opens at Carrickpherish". The Munster Express. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "WFFA – Waterford Film For All". Waterfordfilmforall.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Ryan, Michael (23 April 2018). "RTÉ Archives - Viking and Norman Finds - 1988". RTÉ. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Waterford Methodist Church, Greyfriars, Waterford City". buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Home". Waterford Film Festival. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ McNeice, Katie (14 November 2016). "Waterford Film Festival Announce 2016 Winners". Irish Film & Television Network. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ 10,000 tickets sold for Waterford Music Fest 2011 Archived 26 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Munster Express Online (29 July 2011). Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ "Waterford Festival". waterfordfestival.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007.

- ^ Waterford International Music Festival | May 1 – 13 2012 Archived 7 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Waterfordintlmusicfestival.com. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ Tall Ships Race 2011, Waterford Tall Ships Festival Ireland Archived 13 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Waterfordtallshipsrace.ie (3 July 2011). Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ Imagine Arts Festival, Waterford Ireland Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Discoverwaterfordcity.ie. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ "Waterford Winterval – Ireland's Christmas Festival". winterval.ie. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012.

- ^ Tipton, Gemma (17 August 2015). "Waterford Walls: graffiti artists paint the city out of a corner". Irish Times. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Kane, Conor (24 August 2020). "Street art festival brightens up Waterford's walls". RTÉ News. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Waterford Museum of Treasures in Ireland's Oldest City – Waterford Treasures". waterfordtreasures.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Janvs – Award winning designers of museums, galleries and heritage centres". janvs.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008.

- ^ "Theatre Royal – Entertainment in Waterford, Ireland". theatreroyalwaterford.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Entertainment in Waterford, theatre, movies, music, Garter Lane Arts Centre". garterlane.ie. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008.

- ^ St John’s College sold to Respond By Jamie O’Keeffe Archived 3 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Munster Express, Published on Friday, 20 April 2007 at 12:00 pm

- ^ St Saviours Church, Waterford, Waterford Dominican Community, www.dominicans.ie

- ^ "Saint Patrick's Catholic Church, Great George's Street, Jenkin's Lane, WATERFORD CITY, Waterford, WATERFORD". www.buildingsofireland.ie. Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Christ Church Waterford (Church of Ireland).

- ^ St Patrick's Methodist Church, Methodist Church Waterford

- ^ Waterford Baptist Church

- ^ Anchor Baptist Church, Waterford

- ^ Waterford Quakers

- ^ Halpin, Andrew (2021). "The Long and the short of it: the untold story of Waterford's medieval archery butts". Archaeology Ireland. 35: 30–35.

- ^ Bradley, H.F. (1992). "The topographical development of Scandinavian and Anglo-Norman Waterford". Waterford History and Society: 105–29.

- ^ "Waterford's Apple Market transformed into contemporary urban quarter". Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ 9th Century Settlement found at Woodstown Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine – vikingwaterford.com

- ^ "Waterford Crystal closed amid crippling debts". Usatoday.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Waterford Crystal visitor centre opens". Irish Times. 6 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Strategy for Economic, Social and Cultural Development of Waterford City 2002-2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ Beeson, Trevor (2002). Priests And Prelates: The Daily Telegraph Clerical Obituaries. London: Continuum Books. pp. 4–5; ISBN 0-8264-6337-1

- ^ Morris, Shirley (April 2007). Interior Decoration – A Complete Course. Global Media. pg. 105; ISBN 81-89940-65-1

- ^ Finn, Christina. "50 jobs lost as Citi Bank announce Waterford office closure". Thejournal.ie. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Murphy, William (2014). 21st Century Business Revised Edition. Dublin: CJ Fallon. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-7144-1923-7.

- ^ Irish Motorway Info. "M9 Motorway". irishmotorwayinfo.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "04 - Dublin Waterford" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "12 - Waterford Limerick" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Rail Review 2016 REPORT" (PDF). Nationaltransport.ie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Tiernan, Damien (28 May 2018). "Waterford port freight train contract ceases". RTÉ News and Current Affairs. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ NEW BELVIEW-BALLINA RAIL FREIGHT SERVICE ROLLS OUT Waterford News, September 29, 2021.

- ^ Fodor (29 March 2011). Fodor's Dublin and Southeastern Ireland. Fodor's Travel. p. 286. ISBN 9780307928283. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Fodor (2019). Fodor's Essential Ireland 2019. Fodor's Travel Guides. p. 281. ISBN 9781640970571. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Kerry Airport". buseireann.ie. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Waterford Today". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Ireland's longest greenway opens in Waterford". RTÉ News. 25 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Tony Ryan Obituary". Airlineworld.wordpress.com. 4 October 2007. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Primary Schools in Waterford City Archived 19 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Education Ireland

- ^ Secondary Schools in Waterford City Archived 19 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Education Ireland

- ^ "Mount Sion School Waterford Ireland". mountsion.ie. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ "De La Salle College Waterford". delasallewaterford.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008.

- ^ "Directory Page - St Angela's Secondary School". gov.ie. Department of Education. 4 November 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to Waterford College of Further Education". wcfe.ie. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ^ Simon Harris TD [@SimonHarrisTD] (2 November 2021). "After years of debate and discussion, hard work by so many, today we announce a Technological University for the South East. This is a major moment for access to higher education in the region & transformational for future generations" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Heaney, Steven (2 November 2021). "Merger of Waterford and Carlow ITs into Technological University for South-East confirmed". IrishExaminer.com.

- ^ "Waterfordboatclub.net". Archived from the original on 17 January 2015.

- ^ "Irish Rowing Championships". rowingireland.ie. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014.

- ^ "Waterford Viking Marathon 2015, Saturday June 27th". waterfordvikingmarathon.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014.

- ^ "St Anne's Tennis Club :: Home". www.stannestennis.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Waterford City Rugby Club". facebook.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017.

- ^ "Waterpark Rugby Football Club". waterparkrfc.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014.

- ^ "Ireland Grounds". cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 28 August 2023.[failed verification]

- ^ "Going Home: Brendan Bowyer Is Laid To Rest In His Beloved Waterford". waterford-news.ie. 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Clagget (Claget), Charles". dib.ie. October 2009. doi:10.3318/dib.001670.v1.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2011), "Doonican, Val", The Encyclopedia of Popular Music, p. 756, ISBN 9780857125958

- ^ "Dunne, Seán Christopher". dib.ie. 2009. doi:10.3318/dib.002862.v1.

- ^ "Hugely successful Waterford novelist Megan Nolan returns to Waterford". wlrfm.com. August 2023.

- ^ "Biography by Jason Ankeny". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Who's Who of Jazz (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. p. 376. ISBN 0-85112-580-8.

- ^ Macgee, T.D. (1857). Gallery of Irish Writers: The Irish Writers of the Seventeenth Century. J. Duffy. pp. 90–102.

- ^ Percival Serle, ed. (1949). "Wallace, William Vincent". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Angus and Robertson.

- ^ Serle, Percival (1949). "Hobson, William". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "Meagher, Thomas". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

- ^ Lyons, W.F. (1870). Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher—His Political and Military Career. D. & J. Sadlier & Company. p. 10.

- ^ "Mulcahy, Richard". Dictionary of Irish Biography. 2009. doi:10.3318/dib.006029.v2.

- ^ Webb, Alfred (1878). . A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son.

- ^ "Jim Beglin – one of Waterford's favourite football sons". waterford-news.ie. 2020.

- ^ "Waterford's John O'Shea departs club role to focus on Republic of Ireland". waterfordlive.ie. 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Waterford All Time Greats: Profile #14 Marguerite Moore". waterfordlive.ie. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

External links

[edit]- 914 establishments

- Waterford (city)

- Baronies of County Waterford

- Cities in the Republic of Ireland

- Munster

- Populated coastal places in the Republic of Ireland

- Viking Age populated places

- 10th-century establishments in Ireland

- Populated places established in the 10th century

- Port cities and towns in the Republic of Ireland

- Former boroughs in the Republic of Ireland