Fourth Way

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

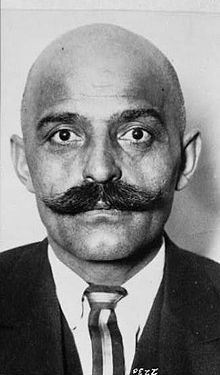

The Fourth Way is an approach to self-development developed by George Gurdjieff over years of travel in the East (c. 1890 – 1912). It combines and harmonizes what he saw as three established traditional "ways" or "schools": first, those of the body; second, the emotions; and third, the mind (specifically that of fakirs, monks and yogis). Students often refer to the Fourth Way as "The Work", "Work on oneself", or "The System". The exact origins of some of Gurdjieff's teachings are unknown, but various sources have been suggested.[1]

The term "Fourth Way" was further used by his student P. D. Ouspensky in his lectures and writings. After Ouspensky's death, his students published a book entitled The Fourth Way based on his lectures. According to this system, the three traditional schools, or ways, "are permanent forms which have survived throughout history mostly unchanged, and are based on religion. Where schools of yogis, monks or fakirs exist, they are barely distinguishable from religious schools. The fourth way differs in that "it is not a permanent way. It has no specific forms or institutions and comes and goes controlled by some particular laws of its own."[2]

When this work is finished, that is to say, when the aim set before it has been accomplished, the fourth way disappears, that is, it disappears from the given place, disappears in its given form, continuing perhaps in another place in another form. Schools of the fourth way exist for the needs of the work which is being carried out in connection with the proposed undertaking. They never exist by themselves as schools for the purpose of education and instruction.[3]

The Fourth Way addresses the question of humanity's place in the Universe and the possibilities of inner development. It emphasizes that people ordinarily live in a state referred to as a semi-hypnotic "waking sleep," while higher levels of consciousness, virtue, and unity of will are possible.

The Fourth Way teaches how to increase and focus attention and energy in various ways, and to minimize day-dreaming and absent-mindedness. This inner development in oneself is the beginning of a possible further process of change, whose aim is to transform man into "what he ought to be."

Overview[edit]

Gurdjieff's followers believed he was a spiritual master,[4] a human being who is fully awake or enlightened. He was also seen as an esotericist or occultist.[5] He agreed that the teaching was esoteric but claimed that none of it was veiled in secrecy but that many people lack the interest or the capability to understand it.[6] Gurdjieff said, "The teaching whose theory is here being set out is completely self supporting and independent of other lines and it has been completely unknown up to the present time."[7]

The Fourth Way teaches that the soul a human individual is born with gets trapped and encapsulated by personality, and stays dormant, leaving one not really conscious, despite believing one is. A person must free the soul by following a teaching which can lead to this aim or "go nowhere" upon death of his body. Should a person be able to receive the teaching and find a school, upon the death of the physical body they will "go elsewhere." Humans are born asleep, live in sleep, and die in sleep, only imagining that they are awake with few exceptions.[8] The ordinary waking "consciousness" of human beings is not consciousness at all but merely a form of sleep."

Gurdjieff taught "sacred dances" or "movements", now known as Gurdjieff movements, which were performed together as a group.[9] He left a body of music, inspired by that which he had heard in remote monasteries and other places, which was written for piano in collaboration with one of his pupils, Thomas de Hartmann.[10]

Three ways[edit]

Gurdjieff taught that traditional paths to spiritual enlightenment followed one of three ways:

- The Way of the Fakir

- The Fakir works to obtain mastery of the attention (self-mastery) through struggles with [controlling] the physical body involving difficult physical exercises and postures.

- The Way of the Monk

- The Monk works to obtain the same mastery of the attention (self-mastery) through struggle with [controlling] the affections, in the domain, as we say, of the heart, which has been emphasized in the west, and come to be known as the way of faith due to its practice particularly in Catholicism.

- The Way of the Yogi

- The Yogi works to obtain the same mastery of the attention (as before: 'self mastery') through struggle with [controlling] mental habits and capabilities.

Gurdjieff insisted that these paths, although they may intend to seek to produce a fully developed human being, tend to cultivate certain faculties at the expense of others. The goal of religion or spirituality was, in fact, to produce a well-balanced, responsive and sane human being capable of dealing with all eventualities that life may present. Gurdjieff therefore made it clear that it was necessary to cultivate a way that integrated and combined the traditional three ways.

Fourth Way[edit]

Gurdjieff said that his Fourth Way was a quicker means than the first three ways because it simultaneously combined work on all three centers rather than focusing on one. It could be followed by ordinary people in everyday life, requiring no retirement into the desert. The Fourth Way does involve certain conditions imposed by a teacher, but blind acceptance of them is discouraged. Each student is advised to do only what they understand and to verify for themselves the teaching's ideas.

Ouspensky documented Gurdjieff as saying that "two or three thousand years ago there were yet other ways which no longer exist and the ways then in existence were not so divided, they stood much closer to one another. The fourth way differs from the old and the new ways by the fact that it is never a permanent way. It has no definite forms and there are no institutions connected with it."[11]

Ouspensky quotes Gurdjieff that there are fake schools and that "It is impossible to recognize a wrong way without knowing the right way. This means that it is no use troubling oneself how to recognize a wrong way. One must think of how to find the right way."[12]

Origins[edit]

In his works, Gurdjieff credits his teachings to a number of more or less mysterious sources:[13]

- Various small sects of 'real' Christians in Asia and the Middle East. Gurdjieff believed that mainstream Christian teachings had become corrupted.

- Various dervishes (he did not use the term 'Sufi')

- Gurdjieff mentions practicing Yoga in his youth but his later comments about Indian fakirs and yogis are dismissive.

- The mysterious Sarmoung monastery in a remote area of central Asia, to which Gurdjieff was led blindfold.

- The non-denominational "Universal Brotherhood".

Attempts to fill out his account have featured:

- Technical vocabulary first appearing in early 19th century Russian freemasonry, derived from Robert Fludd (P. D. Ouspensky)

- Eastern Christianity as detailed in the works of Robin Amis and Boris Mouravieff

- Tibetan Buddhism, according to Jose Tirado.[14]

- Chatral Rinpoche believes that Gurdjieff spent several years in a monastery in the Swat valley.[15]

- James George hypothesizes that Surmang, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in China, is the real Sarmoung monastery.

- Naqshbandi Sufism, (Idries Shah,[16] Rafael Lefort)

- The "stop" exercise is similar to the Uqufi Zamani exercise in Omar Ali-Shah's book on the Rules or Secrets of the Naqshbandi Sufi Order.[17]

- In principle Zoroaster, and explicitly the 12th century Khwajagan Sufi leader, Abdul Khaliq Gajadwani (J. G. Bennett[18])

Teachings and teaching methods[edit]

Basis of teachings[edit]

Present here now[19]

We do not remember ourselves[20]

Conscious Labor is an action where the person who is performing the act is present to what he is doing; not absentminded. At the same time he is striving to perform the act more efficiently.

Intentional suffering is the act of struggling against automatism such as daydreaming, pleasure, food (eating for reasons other than real hunger), etc. In Gurdjieff's book Beelzebub's Tales he states that "the greatest 'intentional suffering' can be obtained in our presences by compelling ourselves to endure the displeasing manifestations of others toward ourselves"[21]

To Gurdjieff, conscious labor and intentional suffering were the basis of all evolution of man.

Self-Observation

Observation of one's own behavior and habits. To observe thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judging or analyzing what is observed.[22]

The Need for Effort

Gurdjieff emphasized that awakening results from consistent, prolonged effort. Such efforts may be made as an act of will after one is already exhausted.

The Many 'I's

This indicates fragmentation of the psyche, the different feelings and thoughts of 'I' in a person: I think, I want, I know best, I prefer, I am happy, I am hungry, I am tired, etc. These have nothing in common with one another and are unaware of each other, arising and vanishing for short periods of time. Hence man usually has no unity in himself, wanting one thing now and another, perhaps contradictory, thing later.

Centers

Gurdjieff classified plants as having one center, animals two and humans three. Centers refer to apparati within a being that dictate specific organic functions. There are three main centers in a man: intellectual, emotional and physical, and two higher centers: higher emotional and higher intellectual.

Body, Essence and Personality

Gurdjieff divided people's being into Essence and Personality.

- Essence – is a "natural part of a person" or "what he is born with"; this is the part of a being which is said to have the ability to evolve.

- Personality – is everything artificial that he has "learned" and "seen".

Cosmic Laws

Gurdjieff focused on two main cosmic laws, the Law of Three and the Law of Seven [citation needed].

- The Law of Seven is described by Gurdjieff as "the first fundamental cosmic law". This law is used to explain processes. The basic use of the law of seven is to explain why nothing in nature and in life constantly occurs in a straight line, that is to say that there are always ups and downs in life which occur lawfully. Examples of this can be noticed in athletic performances, where a high ranked athlete always has periodic downfalls, as well as in nearly all graphs that plot topics that occur over time, such as the economic graphs, population graphs, death-rate graphs and so on. All show parabolic periods that keep rising and falling. Gurdjieff claimed that since these periods occur lawfully based on the law of seven that it is possible to keep a process in a straight line if the necessary shocks were introduced at the right time. A piano keyboard is an example of the law of seven, as the seven notes of the major scale correspond exactly to it.

- The Law of Three is described by Gurdjieff as "the second fundamental cosmic law". This law states that every whole phenomenon is composed of three separate sources, which are Active, Passive and Reconciling or Neutral. This law applies to everything in the universe and humanity, as well as all the structures and processes. The Three Centers in a human, which Gurdjieff said were the Intellectual Centre, the Emotional Centre and the Moving Centre, are an expression of the law of three. Gurdjieff taught his students to think of the law of three forces as essential to transforming the energy of the human being. The process of transformation requires the three actions of affirmation, denial and reconciliation. This law of three separate sources can be considered modern interpretation of early Hindu Philosophy of Gunas, We can see this as Chapters 3, 7, 13, 14, 17 and 18 of Bhagavad Gita discuss Guna in their verses.[23]

How the Law of Seven and Law of Three function together is said to be illustrated on the Fourth Way Enneagram, a nine-pointed symbol which is the central glyph of Gurdjieff's system.

Use of symbols[edit]

In his explanations Gurdjieff often used different symbols such as the Enneagram and the Ray of Creation. Gurdjieff said that "the enneagram is a universal symbol. All knowledge can be included in the enneagram and with the help of the enneagram it can be interpreted ... A man may be quite alone in the desert and he can trace the enneagram in the sand and in it read the eternal laws of the universe. And every time he can learn something new, something he did not know before."[24] The ray of creation is a diagram which represents the Earth's place in the Universe. The diagram has eight levels, each corresponding to Gurdjieff's laws of octaves.

Through the elaboration of the law of octaves and the meaning of the enneagram, Gurdjieff offered his students alternative means of conceptualizing the world and their place in it.

Working conditions and sacred dances[edit]

To provide conditions in which attention could be exercised more intensively, Gurdjieff also taught his pupils "sacred dances" or "movements" which they performed together as a group, and he left a body of music inspired by what he heard in visits to remote monasteries and other places, which was written for piano in collaboration with one of his pupils, Thomas de Hartmann.

Gurdjieff laid emphasis on the idea that the seeker must conduct his or her own search. The teacher cannot do the student's work for the student, but is more of a guide on the path to self-discovery. As a teacher, Gurdjieff specialized in creating conditions for students – conditions in which growth was possible, in which efficient progress could be made by the willing. To find oneself in a set of conditions that a gifted teacher has arranged has another benefit. As Gurdjieff put it, "You must realize that each man has a definite repertoire of roles which he plays in ordinary circumstances ... but put him into even only slightly different circumstances and he is unable to find a suitable role and for a short time he becomes himself."

Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man[edit]

Having migrated for four years after escaping the Russian Revolution with dozens of followers and family members, Gurdjieff settled in France and established his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at the Château Le Prieuré at Fontainebleau-Avon in October 1922.[25] The institute was an esoteric school based on Gurdjieff's Fourth Way teaching. After nearly dying in a car crash in 1924, he recovered and closed down the institute. He began writing All and Everything. From 1930, Gurdjieff made visits to North America where he resumed his teachings.

Ouspensky relates that in the early work with Gurdjieff in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Gurdjieff forbade students from writing down or publishing anything connected with Gurdjieff and his ideas. Gurdjieff said that students of his methods would find themselves unable to transmit correctly what was said in the groups. Later, Gurdjieff relaxed this rule, accepting students who subsequently published accounts of their experiences in the Gurdjieff work.

After Gurdjieff[edit]

After Gurdjieff's death in 1949 a variety of groups around the world have attempted to continue The Gurdjieff Work. The Gurdjieff Foundation, was established in 1953 in New York City by Jeanne de Salzmann in cooperation with other direct pupils.[26] J. G. Bennett ran groups and also made contact with the Subud and Sufi schools to develop The Work in different directions. Maurice Nicoll, a Jungian psychologist, also ran his own groups based on Gurdjieff and Ouspensky's ideas. The French institute was headed for many years by Madam de Salzmann – a direct pupil of Gurdjieff. Under her leadership, the Gurdjieff Societies of London and New York were founded and developed.

A number of offshoots incorporate elements of the Fourth Way, such as:[citation needed]

- Claudio Naranjo's teaching.

- Oscar Ichazo's Arica School

- The Diamond Approach of A. H. Almaas.

The Enneagram is often studied in contexts that do not include other elements of Fourth Way teaching.

References[edit]

- ^ Anthony Storr, Feet of Clay, p. 26, Simon & Schuster, 1997 ISBN 978-0-684-83495-5

- ^ "In Search of the Miraculous" by P.D. Ouspensky p. 312

- ^ P.D. Ouspensky (1949), In Search of the Miraculous, Chapter 15

- ^ Meetings with Remarkable Men, translator's note

- ^ Gurdjieff article in The Skeptic's dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll

- ^ P.D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous, p.38.

- ^ In Search of The Miraculous (Chapter 14)

- ^ P. D. Ouspensky In Search of the Miraculous, p. 66, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1977 ISBN 0-15-644508-5

- ^ "Gurdjieff Heritage Society Book Excerpts". Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ Thomas de Hartmann: A Composer’s Life[permanent dead link] by John Mangan

- ^ "In Search of the Miraculous" by P.D. Ouspensky p. 312

- ^ In Search of The Miraculous (Chapter 10)

- ^ "Sources of Gurdjieff's Teachings" downloadable PDF file

- ^ "Gurdjieff-internet". Archived from the original on 29 October 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ Meetings with Three Tibetan Masters

- ^ Idries Shah: The Way of the Sufi, Part 1, Notes and Bibliography, Note 35

- ^ Omar Ali-Shah:The Rules or Secrets of the Naqshbandi Order. See also: Eleven Naqshbandi principles.

- ^ "The Fourth Way" Bennett's last public lecture, available on CD from J. G. Bennet website).[1]

- ^ Exchanges Within; p 18; John Pentland

- ^ In Search of the Miraculous; p 117; P. D. Ouspensky

- ^ G.I. Gurdjieff (1950). Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson, pg 242

- ^ Gurdjieff & the Further Reaches of Self-Observation, an article by Dennis Lewis

- ^ The Bhagavad Gita. Sargeant, Winthrop, 1903-1986., Chapple, Christopher Key, 1954- (25th anniversary ed.). Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. 2009. ISBN 978-1-4416-0873-4. OCLC 334515703.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ A Lecture by G.I. Gurdjieff

- ^ Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man

- ^ The Gurdjieff Foundation

External links[edit]

Quotations related to Fourth Way at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Fourth Way at Wikiquote Media related to Fourth Way at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fourth Way at Wikimedia Commons