Private Eye

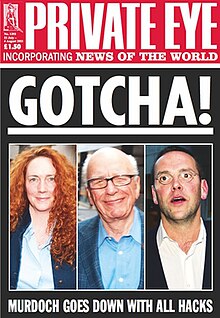

A July 2011 cover following the closure of the News of the World, making ironic use of a famous 1982 headline from The Sun | |

| Editor | Ian Hislop |

|---|---|

| Categories | Satirical news magazine |

| Frequency | Fortnightly |

| Circulation | 233,118 (Jul–Dec 2023) [1] |

| Founded | 1961 |

| Company | Pressdram Ltd |

| Based in | London W1 United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 0032-888X |

Private Eye is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961.[2] It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised for its prominent criticism and lampooning of public figures. It is also known for its in-depth investigative journalism into under-reported scandals and cover-ups.[3]

Private Eye is Britain's best-selling current affairs news magazine,[4] and such is its long-term popularity and impact that many of its recurring in-jokes have entered popular culture in the United Kingdom. The magazine bucks the trend of declining circulation for print media, having recorded its highest-ever circulation in the second half of 2016.[5] It is privately owned and highly profitable.[6]

With a "deeply conservative resistance to change",[7] it has resisted moves to online content or glossy format: it has always been printed on cheap paper and resembles, in format and content, a comic rather than a serious magazine.[6][8] Both its satire and investigative journalism have led to numerous libel suits.[3] It is known for the use of pseudonyms by its contributors, many of whom have been prominent in public life—this even extends to a fictional proprietor, Lord Gnome.[9][10]

History

[edit]The forerunner of Private Eye was The Walopian, an underground magazine published at Shrewsbury School by pupils in the mid-1950s and edited by Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Christopher Booker and Paul Foot. The Walopian (a play on the school magazine name The Salopian) mocked school spirit, traditions and the masters. After National Service, Ingrams and Foot went as undergraduates to Oxford University, where they met future collaborators including Peter Usborne, Andrew Osmond[11] and John Wells.[12]

The magazine was properly begun when they learned of a new printing process, photo-litho offset, which meant that anybody with a typewriter and Letraset could produce a magazine. The publication was initially funded by Osmond and launched in 1961.[13] It is agreed that Osmond suggested the title, and sold many of the early copies in person, in London pubs.[14]

The magazine was initially edited by Booker and designed by Rushton, who drew cartoons for it. Usborne was its first managing director.[15] Its subsequent editor, Ingrams, who was then pursuing a career as an actor, shared the editorship with Booker from around issue number 10 and took over from issue 40. At first, Private Eye was a vehicle for juvenile jokes: an extension of the original school magazine, and an alternative to Punch.

Peter Cook—who in October 1961 founded The Establishment, the first satirical nightclub in London—purchased Private Eye in 1962, together with Nicholas Luard,[16] and was a long-time contributor.[17] Others essential to the development of the magazine were Auberon Waugh, Claud Cockburn (who had run a pre-war scandal sheet, The Week), Barry Fantoni, Gerald Scarfe, Tony Rushton, Patrick Marnham and Candida Betjeman. Christopher Logue was another long-time contributor, providing the column "True Stories", featuring cuttings from the national press. The gossip columnist Nigel Dempster wrote extensively for the magazine before he fell out with Ian Hislop and other writers, while Foot wrote on politics, local government and corruption. The receptionist and general factotum from 1984 to 2014 was Hilary Lowinger.[18]

Ingrams continued as editor until 1986 when he was succeeded by Hislop. Ingrams remains chairman of the holding company.[19]

Style of the magazine

[edit]Private Eye often reports on the misdeeds of powerful and important individuals and, consequently, has received numerous libel writs throughout its history. These include three issued by James Goldsmith (known in the magazine as "(Sir) Jammy Fishpaste" and "Jonah Jammy fingers") and several by Robert Maxwell (known as "Captain Bob"), one of which resulted in the award of costs and reported damages of £225,000, and attacks on the magazine by Maxwell through a book, Malice in Wonderland, and a one-off magazine, Not Private Eye. Its defenders point out that it often carries news that the mainstream press will not print for fear of legal reprisals or because the material is of minority interest.

As well as covering a wide range of current affairs, Private Eye is also known for highlighting the errors and hypocritical behaviour of newspapers in the "Street of Shame" column, named after Fleet Street, the former home of many papers. It reports on parliamentary and national political issues, with regional and local politics covered in equal depth under the "Rotten Boroughs" column (named after the rotten boroughs of the pre-Reform Act of 1832 House of Commons). Extensive investigative journalism is published under the "In the Back" section, often tackling cover-ups and unreported scandals. A financial column called "In the City" (referring to the City of London), written by Michael Gillard under the pseudonym "Slicker", has exposed several significant financial scandals and described unethical business practices.

Some contributors to Private Eye are media figures or specialists in their field who write anonymously, often under humorous pseudonyms, such as "Dr B Ching" (a reference to the Beeching cuts) who writes the "Signal Failures" column about the railways. Stories sometimes originate from writers for more mainstream publications who cannot get their stories published by their main employers.

Private Eye has traditionally lagged other magazines in adopting new typesetting and printing technologies. At the start, it was laid out with scissors and paste and typed on three IBM Electric typewriters—italics, pica and elite—lending an amateurish look to the pages. For some years after layout tools became available the magazine retained this technique to maintain its look, although the three older typewriters were replaced with an IBM composer. Today the magazine is still predominantly in black and white (though the cover and some cartoons inside appear in colour) and there is more text and less white space than is typical for a modern magazine. Much of the text is printed in the standard Times New Roman font. The former "Colour Section" was printed in black and white like the rest of the magazine: only the content was colourful.

Notable columns

[edit]A series of parody columns referring to the Prime Minister of the day has been a long-term feature of Private Eye. While satirical, during the 1980s, Ingrams and John Wells wrote an affectionate series of fictional letters from Denis Thatcher to Bill Deedes in the Dear Bill column, mocking Thatcher as an amiable, golf-playing drunk. The column was collected in a series of books and became a stage play ("Anyone for Denis?") in which Wells played the fictional Denis, a character now inextricably "blurred with the real historical figure", according to Ingrams.[20]

In The Back is an investigative journalism section notably associated with journalist Paul Foot[21] (the Eye has always published its investigative journalism at the back of the magazine).[22] Private Eye was one of the journalistic organisations involved in sifting and analysing the Paradise Papers, and this commentary appears in In the Back.[23][24]

Nooks and Corners (originally Nooks and Corners of the New Barbarism), an architectural column severely critical of architectural vandalism and "barbarism",[25] notably modernism and brutalism,[26] was originally founded by John Betjeman in 1971 (his first article attacked a building praised by his enemy Nikolaus Pevsner)[27] and carried on by his daughter Candida Lycett Green.[28][29] For four decades beginning in 1978, it was edited by Gavin Stamp under the pseudonym Piloti.[29] The column notably features a discussion of the state of public architecture and especially the preservation (or otherwise) of Britain's architectural heritage.[30]

Street of Shame is a column addressing journalistic misconduct and excesses,[31][32] hypocrisy, and undue influence by proprietors and editors, mostly sourced from tipoffs[33]—it sometimes serves as a venue for the settling of scores within the trade,[34] and is a source of friction with editors.[33] This work formed the basis of much of Ian Hislop's testimony to the Leveson Inquiry, and Leveson was complimentary about the magazine and the column.[35] The term street of shame is a reference to Fleet Street, the former centre of British journalism, and has become synonymous with it.[9][36][37]

The Rotten Boroughs column focuses on actual or alleged wrongdoing in local or regional governments and elections, for example, corruption, nepotism, hypocrisy and incompetence. The column's name derives from the 18th-century rotten boroughs.

There are also several recurring miniature sections.

Special editions

[edit]The magazine has occasionally published special editions dedicated to the reporting of particular events, such as government inadequacy over the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak, the conviction in 2001 of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for the 1988 Lockerbie bombing (an incident regularly covered since by "In the Back"), and the purported MMR vaccine controversy (since shown to be medical fraud committed by Andrew Wakefield) in 2002.

A special issue was published in 2004 to mark the death of long-time contributor Paul Foot. In 2005, The Guardian and Private Eye established the Paul Foot Award (referred to colloquially as the "Footy"), with an annual £10,000 prize fund, for investigative/campaigning journalism in memory of Foot.[38]

In-jokes

[edit]The magazine has many recurring in-jokes and convoluted references, often comprehensible only to those who have read the magazine for many years. They include euphemisms designed to avoid the notoriously plaintiff-friendly English libel laws, such as replacing the word "drunk" with "tired and emotional",[39][40] or using the phrase "Ugandan discussions" to denote illicit sexual exploits;[39] and more obvious parodies using easily recognisable stereotypes, such as the lampooning of Conservative MPs as "Sir Bufton Tufton". Some of the terms have fallen into disuse when their hidden meanings have become better known.

The magazine often deliberately misspells the names of certain organisations, such as "Crapita" for the outsourcing company Capita, "Carter-Fuck" for the law firm Carter-Ruck, and "The Grauniad" for The Guardian (the latter a reference to the newspaper's frequent typos in its days as The Manchester Guardian). Certain individuals may be referred to by another name, for example, Piers Morgan as "Piers Moron", Richard Branson as "Beardie", Rupert Murdoch as the "Dirty Digger", and Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III as "Brenda" and "Brian", respectively.

The first half of each issue, which consists chiefly of news reporting and investigative journalism, tends to include these in-jokes more subtly, to maintain journalistic integrity, while the second half, generally characterised by unrestrained parody and cutting humour, tends to present itself in a more confrontational way.

Cartoons

[edit]As well as many one-off cartoons, Private Eye features several regular comic strips:

- Apparently by Mike Barfield – satirising day-to-day life or pop trends

- Celeb by Charles Peattie and Mark Warren, collectively known as Ligger – a strip about a celebrity rock star named Gary Bloke, which first appeared in 1987. A BBC sitcom version was spun off in 2002.[41]

- Desperate Business by Modern Toss – stereotypes a range of professions, such as an estate agent showing a couple a minuscule house, with the caption: "It's a bit smaller than it looked on your website".

- EUphemisms by RGJ – features a European Union bureaucrat making a statement, with a caption suggesting what it means in real terms, depicting the EU in a negative or hypocritical light. For example, an EU official declares: "Punishing Britain for Brexit would show the world we've lost the plot", with the caption reading: "We're going to punish Britain for Brexit. We've lost the plot".

- Fallen Angels – a regular cartoon with a caption depicting problems (often bureaucratic) in the National Health Service

- First Drafts by Simon Pearsell – original drafts of popular books

- Forgotten Moments in Music History – features cryptic references to notable songs and performers.

- It's Grim Up North London by Knife and Packer – a satire about Islington "trendies" which has been featured since 1999.

- Logos as They Should Be – a satire of logos from some of the world's most-known companies

- The Premiersh*ts by Paul Wood – a satire of professional football and footballers, in the Premier League

- Snipcock & Tweed by Nick Newman – about two book publishers

- Supermodels by Neil Kerber – satirising the lifestyle of supermodels; the characters are unfeasibly thin.

- Yobs and Yobettes by Tony Husband – satirising yob culture, featuring since the late 1980s

- Young British Artists by Birch – a spoof of the Young British Artists movement such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst

Some of the magazine's former cartoon strips include:

- The Adventures of Mr Millibean – former Leader of the Opposition, Ed Miliband, is portrayed as Rowan Atkinson's Mr. Bean

- Andy Capp-in-Ring – a parody of Andy Capp, satirising Labour leadership candidate Andy Burnham and his rivals, portraying Burnham as Capp

- Barry McKenzie – a popular strip in the mid-1960s detailing the adventures of an expatriate Australian in Earl's Court, London and elsewhere, written by Barry Humphries and drawn by Nicholas Garland

- Battle for Britain – a satire of British politics (1983–87) in terms of a World War II war comic

- The Broon-ites – a pastiche of the Scottish cartoon strip The Broons, featuring Gordon Brown and his close associates. The speech bubbles are written in broad Scots.

- Dan Dire, Pilot of the Future? and Tony Blair, Pilot for the Foreseeable Future – parodies of the Dan Dare comics of the 1950s, satirising (respectively) Neil Kinnock's time as Labour leader, and Tony Blair's Labour government

- Dave Snooty and his New Pals – drawn in the style of The Beano, it parodied David Cameron as "Dave Snooty" (a reference to the Beano character "Lord Snooty"), involved in public schoolboy-type behaviour with members of his cabinet. Cameron is portrayed as wearing an Eton College uniform with bow tie, tailcoat, waistcoat and pinstriped trousers.

- The Directors by Dredge & Rigg – commented on the excesses of boardroom fat cats.

- The Cloggies by Bill Tidy – about clogging dancers

- The Commuters by Grizelda – followed the efforts of two commuters to get a train to work.

- Global Warming: The Plus Side – a satire of the effects of global warming, suggesting mock "positive" impacts of the phenomena, such as bus-sized marrows in village vegetable competitions, vastly decreased fossil prices due to melting permafrost, and the proliferation of British citrus orchards

- Gogglebollox by Goddard – a satirical take on recent television shows

- Great Bores of Today by Michael Heath

- The Has-Beano – a pastiche of The Beano used to satirise The Spectator and Boris Johnson (who features as the lead character, Boris the Menace)

- Hom Sap by David Austin

- Liz – a cartoon about the Royal Family drawn by Cutter Perkins and RGJ in the style of the comic magazine Viz (with the speech in Geordie dialect). Ran from issue 801 to 833.

- Meet the Clintstones – The Prehistoric First Family – drawn in the style of The Flintstones, this was a parody of Bill and Hillary Clinton during his presidency and the 2008 US presidential election.

- Off Your Trolley by Reeve & Way – is set in an NHS hospital.

- The Regulars also by Michael Heath – is based on the drinking scene at the Coach and Horses pub in London (a regular meeting place for the magazine's staff and guests), and features the catchphrase "Jeff bin in?" (a reference to pub regular, the journalist Jeffrey Bernard).

- Scenes You Seldom See by Barry Fantoni – satirising the habits of British people by portraying the opposite of what is the accepted norm.

At various times, Private Eye has also used the work of Ralph Steadman, Wally Fawkes, Timothy Birdsall, Martin Honeysett, Willie Rushton, Gerald Scarfe, Robert Thompson, Ken Pyne, Geoff Thompson, "Jorodo", Ed McLachlan, Simon Pearsall, Kevin Woodcock, Brian Bagnall, Kathryn Lamb and George Adamson.

Other products

[edit]Private Eye has, from time to time, produced various spin-offs from the magazine, including:

- Books, e.g. annuals, cartoon collections and investigative pamphlets;

- Audio recordings;

- Private Eye TV, a 1971 BBC TV version of the magazine; and

- Memorabilia and commemorative products, such as Christmas cards.

Private Eye Extras

[edit]- Page 94, The Private Eye Podcast since Episode 1, 4 March 2015,[42] named after the running joke continued on page 94 and hosted by Andrew Hunter Murray.

- Eyeplayer (see iPlayer) Videos and Audio since 2008.[43] Flash, hosted MP3s, and YouTube videos. Including phone-related pieces,[44] audio performances at the Lyttelton Theatre, and Private Eye: A Review Of 2016, 2015 and 2014.

- Covers Library[45] – Issue 1 – 25 October 1961 to present

- Councillors Map[46] – interactive map of local councillors who have not paid their council tax

- UK Tax Haven Map[47] – searchable map of properties, in England and Wales, owned by offshore companies

- The Eye At 50 Blog[48] – February 2009 to September 2013

- Cyril Smith[49] – Archive of the original stories that ran in Private Eye 454 and the Rochdale Alternative Press (RAP), in 1979, involving the establishment of cover-up child abuse by the late Liberal MP Sir Cyril Smith. In May 2022,[50] in an article titled "Cesspit News", Private Eye reminded readers that the late anti-gay "God's Cop" Sir James Anderton had ignored the decades-long abuse by Smith of boys in care.

Criticism and controversy

[edit]Diana, Princess of Wales

[edit]

Some have found the magazine's irreverence and sometimes controversial humour offensive. Following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997, Private Eye printed a cover headed "Media to blame". Under this headline was a picture of many hundreds of people outside Buckingham Palace, with one person commenting that the papers were "a disgrace", another agreeing, saying that it was impossible to get one anywhere, and another saying, "Borrow mine. It's got a picture of the car."[51]

Following the abrupt change in reporting from newspapers immediately following her death, the issue also featured a mock retraction from "all newspapers" of everything negative that they had ever said about Diana. This was enough to cause a flood of complaints and the temporary removal of the magazine from the shelves of some newsagents. These included WHSmith, which had previously refused to stock Private Eye until well into the 1970s and was characterised in the magazine as "WH Smugg" or "WH Smut" on account of its policy of stocking pornographic magazines.

Other complaints

[edit]The issues that followed the Ladbroke Grove rail crash in 1999 (number 987), the September 11 attacks of 2001 (number 1037; the magazine even included a special "subscription cancellation coupon" for disgruntled readers to send in) and the Soham murders of 2002 all attracted similar complaints. Following the 7/7 London bombings the magazine's cover (issue number 1137) featured Prime Minister Tony Blair saying to London mayor Ken Livingstone: "We must track down the evil mastermind behind the bombers...", to which Livingstone replies: "...and invite him around for tea", about his controversial invitation of the Islamic theologian Yusuf al-Qaradawi to London.[52]

MMR vaccine

[edit]During the early 2000s Private Eye published many stories on the MMR vaccine controversy, supporting the interpretation by Andrew Wakefield of published research in The Lancet by the Royal Free Hospital's Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group, which described an apparent link between the vaccine and autism and bowel problems. Many of these stories accused medical researchers who supported the vaccine's safety of having conflicts of interest because of funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Initially dismissive of Wakefield, the magazine rapidly moved to support him, in 2002 publishing a 32-page MMR Special Report that supported Wakefield's assertion that MMR vaccines "should be given individually at not less than one-year intervals." The British Medical Journal issued a contemporary press release[53] that concluded: "The Eye report is dangerous in that it is likely to be read by people who are concerned about the safety of the vaccine. A doubting parent who reads this might be convinced there is a genuine problem, and the absence of any proper references will prevent them from checking the many misleading statements."

In a review article published in 2010, after Wakefield was disciplined by the General Medical Council, regular columnist Phil Hammond, who contributes to the "Medicine Balls" column under the pseudonym "MD", stated that: "Private Eye got it wrong in its coverage of MMR" in maintaining its support for Wakefield's position long after shortcomings in his work had emerged.[54]

Accusations of hostility against unions

[edit]Senior figures in the trade union movement have accused the publication of having a classist anti-union bias, with Unite chief of staff Andrew Murray describing Private Eye as "a publication of assiduous public school boys" and adding that it has "never once written anything about trade unions that isn't informed by cynicism and hostility".[55] The Socialist Worker also wrote that "For the past 50 years, the satirical magazine Private Eye has upset and enraged the powerful. Its mix of humour and investigation has tirelessly challenged the hypocrisy of the elite. ... But it also has serious weaknesses. Among the witty—if sometimes tired—spoof articles and cartoons, there is a nasty streak of snobbery and prejudice. Its jokes about the poor, women and young people rely on lazy stereotypes you might expect from the columns of the Daily Mail. It is the anti-establishment journal of the establishment."[56]

Blasphemy

[edit]The 2004 Christmas issue received many complaints after it featured Pieter Bruegel's painting of a nativity scene, in which one wise man said to another: "Apparently, it's David Blunkett's" (who at the time was involved in a scandal in which he was thought to have impregnated a married woman). Many readers sent letters accusing the magazine of blasphemy and anti-Christian attitudes. One stated that the "witless, gutless buggers wouldn't dare mock Islam". It has, however, regularly published Islam-related humour such as the cartoon which portrayed a "Taliban careers master asking a pupil: What would you like to be when you blow up?".[57]

Many letters in the first issue of 2005 disagreed with the former readers' complaints, and some were parodies of those letters, "complaining" about the following issue's cover[58]—a cartoon depicting Santa's sleigh shredded by a wind farm: one said: "To use a picture of Our Lord Father Christmas and his Holy Reindeer being torn limb from limb while flying over a windfarm is inappropriate and blasphemous."

"Fake news"

[edit]In November 2016, Private Eye's official website appeared on a list of over 150 "fake news" websites compiled by Melissa Zimdars, a US lecturer. The site was listed as a source that is "purposefully fake with the intent of satire/comedy, which can offer important critical commentary on politics and society, but have the potential to be shared as actual/literal news."[59] The Eye rejected any such classification, saying its site "contains none of these things, as the small selection of stories online are drawn from the journalism pages of the magazine", adding that "even US college students might recognise that the Headmistress's letter is not really from a troubled high school".[60] Zimdars later removed the website from her list, after the Eye had contacted her for clarification.[60]

Israel–Hamas war cover

[edit]In 2023, Private Eye published a satirical cover on the Israel–Hamas war, reading "This magazine may contain some criticism of the Israeli government and may suggest that killing everyone in Gaza as revenge for Hamas atrocities may not be a good long-term solution to the problems of the region." The magazine was both criticized and praised for its stance, with some accusing the magazine of antisemitism, while others applauded its bravery in criticizing the Israeli government. Critics such as investigative journalist David Collier condemned the magazine, while supporters defended its critique as not antisemitic but a legitimate questioning of the proportionality of Israel's response.[61]

Libel cases

[edit]Ian Hislop is listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the most sued man in English legal history.[62][63][64][65]

- AM: (Adam Macqueen)

- IH: (Ian Hislop)

- AM: There’s this fact floating around about you that you’re ‘the most sued man in history’…

- IH: Says who?

- AM: Says Wikipedia, I think.

- IH: Yeah, yeah. Must be true!

- AM: In terms of libel cases, would you say the Eye is below or above average?

- IH: In terms of everyone else, or generally? Well, you know, libel collapsed completely. Members of the libel bar had to retrain! The great old days went. It was partly our fault, for whingeing about the need to change the law and then it got changed. Sutcliffe[66][67][68] was the turnaround, it meant the court of appeal could cap libel damages, the judge was allowed to direct the jury as to amount, everything that had been mad about it started to be changed… It created a real sea change: there was a feeling that if you went to court you might lose. For most of the 80s, you just won, or you settled. So the actual number of libel actions went way down for us. And partly I feel because the journalism was more robust, and stouter. And we did a lot more telling people to fuck off at an early stage, and a lot more winning outside the court. I think at the moment we’re all worried about injunctions and privacy, the whole new game seems to be occupying vast amounts of time and money. And libel has become, touch wood, less of an issue.[69][70]

Private Eye has long been known for attracting libel lawsuits which, in English law, can easily lead to the award of damages.[71] The publication "sets aside almost a quarter of its turnover for paying out in libel defeats"[72] although the magazine frequently finds other ways to defuse legal tensions, such as by printing letters from aggrieved parties. As editor since 1986, Ian Hislop is one of the most sued people in Britain.[65] From 1969 to the mid-1980s, the magazine was represented by human rights lawyer Geoffrey Bindman.[73]

The writer Colin Watson was the first person to successfully sue Private Eye, objecting to being described as "the little-known author who ... was writing a novel, very Wodehouse but without jokes". He was awarded £750.[74]

The cover of the tenth-anniversary issue in 1971 (number 257) showed a cartoon headstone inscribed with an extensive list of well-known names, and the epitaph: "They did not sue in vain".[75]

In the 1971 case of Arkell v Pressdram,[76] Arkell's lawyers wrote a letter which concluded: "His attitude to damages will be governed by the nature of your reply." Private Eye responded: "We acknowledge your letter of 29th April referring to Mr J. Arkell. We note that Mr Arkell's attitude to damages will be governed by the nature of our reply and would therefore be grateful if you would inform us what his attitude to damages would be, were he to learn that the nature of our reply is as follows: fuck off."[77] The plaintiff withdrew the threatened lawsuit.[78] The magazine has since used this exchange as a euphemism for a blunt and coarse dismissal, i.e.: "We refer you to the reply given in the case of Arkell v. Pressdram".[79][80] As with "tired and emotional" this usage has spread beyond the magazine.

In 1976 James Goldsmith brought criminal libel charges against the magazine, meaning that if found guilty, editor Richard Ingrams and the author of the article, Patrick Marnham, could be imprisoned. He sued over allegations that he had conspired with the Clermont Set to assist Lord Lucan to evade the police, who wanted him in connection with the murder of his children's nanny. Goldsmith won a partial victory and eventually settled with the magazine. The case threatened to bankrupt Private Eye, which turned to its readers for financial support in the form of a "Goldenballs Fund". Goldsmith was referred to as "Jaws". Goldsmith's solicitor Peter Carter-Ruck was involved in many litigation cases against Private Eye; the magazine refers to his firm as "Carter-Fuck".[81][82]

Robert Maxwell won a significant sum from the magazine when he sued over their suggestion that he looked like a criminal. Hislop claimed that his summary of the case: "I've just given a fat cheque to a fat Czech" was the only example of a joke being told on News at Ten.

Sonia Sutcliffe, wife of the "Yorkshire Ripper" Peter Sutcliffe, sued over allegations in January 1981 that she had used her connection to her husband to make money.[83] Outside the court in May 1989, Hislop quipped about the then-record award of £600,000 in damages: "If that's justice then I'm a banana."[84] The sum was reduced on appeal to £60,000.[84] Readers raised a considerable sum in the "Bananaballs Fund", and Private Eye donated the surplus to the families of Peter Sutcliffe's victims. In Sonia Sutcliffe's 1990 libel case against the News of the World, it emerged that she had indeed benefited financially from her husband's crimes, although the details of Private Eye's article had been inaccurate.[83]

In 1994, retired police inspector Gordon Anglesea successfully sued the Eye and three other media outlets for libel over allegations that he had indecently assaulted under-aged boys in Wrexham in the 1980s. In October 2016, he was convicted of historic sex offences.[85] Hislop said the magazine would not attempt to recover the £80,000 damages awarded to Anglesea, stating: "I can't help thinking of the witnesses who came forward to assist our case at the time, one of whom later committed suicide telling his wife that he never got over not being believed. Private Eye will not be looking to get our money back from the libel damages. Others have paid a far higher price."[86] Anglesea died in December 2016, six weeks into a 12-year prison sentence.[87]

In 1999, former Hackney London Borough Council executive Samuel Yeboah won substantial damages and an apology after the Rotten Borough column "at least 13 times" described him as corrupt and claimed he used "the race card" to avoid criticism.[88]

A victory for the magazine came in late 2001 when a libel case brought by Cornish chartered accountant John Stuart Condliffe was dropped after six weeks with an out-of-court settlement in which Condliffe paid £100,000 towards the Eye's defence.[89] Writing in The Guardian, Jessica Hodgson noted, "The victory against Condliffe—who was represented by top media firm Peter Carter-Ruck and partners—is a big psychological victory for the magazine".[89]

In 2009, Private Eye successfully challenged an injunction brought against it by Michael Napier, the former head of the Law Society, who had sought to claim "confidentiality" over a report that he had been disciplined by the Law Society for a conflict of interest.[90] The ruling had wider significance in that it allowed other rulings by the Law Society to be publicised.[91]

Ownership

[edit]The magazine is owned by an eclectic group of people and is published by a limited company, Pressdram Ltd,[92] which was bought as an "off the shelf" company by Peter Cook in November 1961.

Private Eye does not publish a list of its editors, writers, designers and staff. In 1981 the book The Private Eye Story stated that the owners were Cook, who owned most of the shares, with smaller shareholders including actors Dirk Bogarde and Jane Asher, and several of those involved with the founding of the magazine. Most of those on the list have since died, however, and it is unclear what happened to their shareholdings. Those concerned are contractually only able to sell their shares at the price they originally paid for them.

Shareholders as of the annual company return dated 26 March 2021[update], including shareholders who have inherited shares, are:

- Jane Asher

- Elizabeth Cook

- The executor of the estate of Lord Faringdon

- Ian Hislop (also a director)

- Private Eye (Productions) Ltd

- Anthony Rushton (also a director)

- The executor of the estate of Sarah Seymour

- The Private Eye Trust

- Peter Usborne (1937–2023)

- Brock van den Bogaerde (a nephew of Bogarde)

- Sheila Molnar

- Geoff Elwell (also the company secretary).

Within its pages, the magazine always refers to its owner as the mythical proprietor "Lord Gnome", a satirical dig at autocratic press barons.

Logo

[edit]The magazine's masthead features a cartoon logo of an armoured knight, Gnitty, with a bent sword, parodying the "Crusader" logo of the Daily Express. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gnitty was pictured wearing a mask.[93]

The logo for the magazine's news page is a naked Mr Punch caressing his erect and oversized penis while riding a donkey and hugging a female admirer. It is a detail from a frieze by "Dickie" Doyle that once formed the masthead of Punch magazine, which the editors of Private Eye had come to loathe for its perceived descent into complacency. The image, hidden away in the detail of the frieze, had appeared on the cover of Punch for nearly a century and was noticed by Malcolm Muggeridge during a guest-editing spot on Private Eye. The "Rabelaisian gnome", as the character was called, was enlarged by Gerald Scarfe and put on the front cover of issue 69 in 1964 at full size. He was then formally adopted as a mascot on the inside pages, as a symbol of the old, radical incarnation of Punch magazine that the Eye admired.

The masthead text was designed by Matthew Carter, who would later design the popular web fonts Verdana and Georgia, and the Windows 95 interface font Tahoma.[94] He wrote, "Nick Luard [then co-owner] wanted to change Private Eye into a glossy magazine and asked me to design it. I realised that this was a hopeless idea once I had met Christopher Booker, Richard Ingrams and Willie Rushton."[95]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Private Eye – circulation". Audit Bureau of Circulations . 20 February 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Covers Library: Issue 1". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b Douglas, Torin (14 October 2011). "Private Eye and public scandals". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Dowell, Ben (16 February 2012). "Private Eye hits highest circulation for more than 25 years". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Private Eye hits highest circulation in 55-year history 'which is quite something given that print is meant to be dead'". Press Gazette. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b Erlanger, Steven (11 December 2015). "An Enduring and Erudite Court Jester in Britain". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Anthony, Andrew (9 April 2000). "The laughing Gnome". The Observer. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "Ian Hislop: Provocateur in the public eye". 30 April 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Alan Cowell: Letter from Britain". The New York Times. 30 June 2005. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Barendt, E. M. (2016). Anonymous speech: literature, law and politics. Oxford. p. 35. ISBN 9781849466134. OCLC 940796081.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Andrew Osmond – Obituary". The Guardian. 19 April 1999. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Neal, Toby. "Private Eye founder and former Shrewsbury School pupil Christopher Booker dies at 81". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Private Eye at 60 shows winning formula of bad jokes and brilliant journalism". The National. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Eye and mighty: 50 years on the satirical highway". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "'Genius' children's publisher Peter Usborne dies aged 85". The Irish News. 31 March 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Peter Cook". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Remembering Peter Cook: 'The Funniest Man Who Ever Drew Breath'". vice.com. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Hilary Lowinger, long-serving gatekeeper, counsellor and keeper of secrets at Private Eye – obituary". The Telegraph. 1 September 2023. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Press Conference With...(or without) RICHARD INGRAMS". Press Gazette. 15 December 2005.

- ^ Ingrams, Richard (12 June 2005). "Diary: Dishonourable, dishonest". The Observer. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ McGreevy, Ronan (19 July 2004). "Paul Foot, crusading journalist, dies at 66". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Publish and be damned". eyemagazine.com. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Walker, James (6 November 2017). "Some 380 journalists including BBC, Guardian and Private Eye work with ICIJ on 'Paradise Papers' tax havens data leak". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Peck, Tom (17 November 2017). "Philip May has 'questions to answer' over Paradise Papers". The Independent. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Gavin Stamp: Passion, Polemic and Piloti". architecture.com. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Calder, Barnabas (21 April 2016). Raw concrete: the beauty of brutalism. London. p. 331. ISBN 9781448151295. OCLC 1012156615.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "ANOTHER VISION OF BRITAIN » 13 Jan 1990 » The Spectator Archive". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "British architecture historian Gavin Stamp passes away at 69". Archpaper.com. 31 December 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ a b Jack, Ian (7 January 2018). "Gavin Stamp obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Laughing at architecture : architectural histories of humour, satire and wit. London: Bloomsbury. 29 November 2018. pp. Introduction, note 6. ISBN 9781350022782. OCLC 1030446818.

- ^ "I wish we had gone harder, earlier on hacking story, says Times Editor". The Times. 17 January 2012. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "UK satire's scourge of power: Private Eye hits 50". Reuters. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ a b Sabbagh, Dan (17 January 2012). "Leveson inquiry: Ian Hislop claims PCC would not give him a fair hearing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ McCormack, David (16 May 2006). "Private Eye: more than a gossip rag". PR week. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Castella, Tom de (30 October 2013). "Press regulation: The 10 major questions". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Cassidy, John (20 November 2012). "Second Shoe Drops in Fleet Street Phone-Hacking Scandal". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "The Street of Shame responds". The Economist. 21 January 2012. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "The Paul Foot Award for campaigning journalism". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b Kelly, Jon (15 May 2013). "The 10 most scandalous euphemisms". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Where does the term "tired and emotional", meaning drunk, originate?". Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Celeb rocks on and on". BBC News. 6 September 2002. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Sawyer, Miranda (12 April 2015). "The week in radio: Codes that Changed the World; Page 94, The Private Eye podcast; The Casebook of Max and Ivan". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Eyeplayer Archive 2008". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Vodafone's Swiss Swizz". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Covers Library". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Pay up, pay up and play the game!". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Selling England (and Wales) by the pound". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "The Eye At 50 Blog". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Cyril Smith Archive". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Private Eye issue 1574

- ^ "Private Eye Issue 932". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ^ "Private Eye Issue 1137". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ^ Elliman, David; Bedford, Helen (18 May 2002). "Private Eye Special Report on MMR". The BMJ: 1224. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1224. S2CID 70659012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Second Opinion: the Editor asks M.D. to peer review Private Eye's MMR coverage". Private Eye (1256). Pressdram Ltd: 17. February 2010. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Blackleg (15 April 2016). "TUC News". Private Eye. No. 1416. p. 20.

Unite chief of staff Andrew Murray made much of the Eye's coverage of [the expulsion of David Beaumont from Unite], telling the panel: 'Private Eye is ... a publication of assiduous [sic] public school boys which has never, never once written anything about trade unions that isn't informed by cynicism and hostility.'

- ^ Ward, Patrick (1 November 2011). "Private Eye: The First 50 Years". Socialist Worker. No. 2276. Socialist Workers Party. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Andy McSmith's Diary: Bad taste proves sketchy". The Independent. 14 January 2014. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Private Eye Issue 1122". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ^ Hughes, Owen (16 November 2016). "Breitbart and Private Eye among websites accused of false, misleading, clickbait or satirical 'news'". International Business Times UK. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Red-Facebook". Private Eye. No. 1432. Pressdram Ltd. November–December 2016. p. 16.

- ^ "Private Eye sparks debate with Israel-Hamas war cover". The National. 19 October 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ "Satire, libel and investigative journalism: 50 years of Private Eye". Yahoo News. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Evidence submitted by Ian Hislop, Editor, Private Eye". Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Eye's up". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b Byrne, Ciar (23 October 2006). "Ian Hislop: My 20 years at the "Eye"". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. (27 May 1989). "British Defamation Study". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

A jury's libel award of $960,000 against Private Eye, the satirical British magazine, this week has prompted the Government to undertake a review of defamation law

- ^ "Sutcliffe v Pressdram Ltd". [1989] EWCA Civ J1019-6. 19 October 1989.

- ^ "Attorney General v Hislop". [1990] EWHC J0726-1. 26 July 1990.

- ^ "Private Eye Magazine | Official Site - the UK's number one best-selling news and current affairs magazine, edited by Ian Hislop". www.private-eye.co.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Ian Hislop's top tip for not getting sued: 'allegedly' doesn't work". Radio Times. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Private Eye and public scandals". BBC News. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Hodgson, Jessica (7 November 2001). "Hislop savours first libel victory". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Robins, Jon (13 November 2001). "Forty years old and fighting fit". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ Bunce, Kim (7 October 2001). "The needle of the Eye". The Observer. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ "Covers No. 257". Private Eye. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Correspondence in full". National Association of Science Writers. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Without prejudice". Private Eye. No. 263–264, 266–283, 286–288. 1972. p. ccxxvii.

- ^ Usher, Shaun, ed. (11 October 2016). Letters of Note: Volume 2: An Eclectic Collection of Correspondence Deserving of a Wider Audience. Chronicle Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4521-5903-4.

- ^ Macqueen 2011, pp. 27, 28

- ^ "Letters". Private Eye (1221). London: Pressdram Ltd: 13. October 2008.

Mr Callaghan is referred to the Eye's reply in the famous case of Arkell v. Pressdram (1971).

- ^ "A-list libel lawyer dies". BBC News. 21 December 2003. Archived from the original on 23 December 2003. Retrieved 15 March 2006.

- ^ "Obituary: Peter Carter-Ruck". The Independent. 22 December 2003. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ a b Greenslade, Roy (2004). Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda. London: Pan Macmillan. pp. 440–441. ISBN 9780330393768.

- ^ a b "On This Day, 1989". BBC. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Gordon Anglesea: Former policeman sentenced to 12 years". BBC News. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Private Eye won't seek repayment of damages after Gordon Anglesea conviction as 'others have paid a far higher price'". Press Gazette. 24 October 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Paedophile ex-police officer dies in hospital". Sky News. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Private Eye loses race slur case". BBC News. 19 February 1999.

- ^ a b Hodgson, Jessica (7 November 2001). "Private Eye hails libel victory". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Private Eye Wins Court Case!". Private Eye. No. 1237. 29 May 2009. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009.

- ^ Gibb, Frances (21 May 2009). "Failure to gag Private Eye clears the way to publication of rulings against lawyers". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011.

- ^ "Pressdram". GOV.UK – Find and update company information. Companies House. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

PRESSDRAM LIMITED

C/O MENZIES LLP

LYNTON HOUSE

7–12 TAVISTOCK SQUARE

LONDON WC1H 9LT

Company No. 00708923

Date of Incorporation: 24 November 1961 - ^ "Boris Urges Spending Spree". Private Eye. No. 1524. Pressdram Ltd. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Walters, John. "Matthew Carter's timeless typographic masthead for Private Eye magazine". Eye. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Carter, Matthew. "Carter's Battered Stat". Eye. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Bryant, Mark (January 2007). "The Satirical Eye". History Today. Vol. 57, no. 1.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2002). That Was Satire That Was. Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-1393-9.

- Carpenter, Humphrey. (2003) A great, silly grin: The British satire boom of the 1960s (Da Capo Press, 2003).

- Hislop, Ian (1990). The Complete Gnome Mart Catalogue. Corgi. ISBN 0552137529.

- Ingrams, Richard (1993). Goldenballs!. Harriman House. ISBN 1897597037.

- Ingrams, Richard (1971). The Life and Times of Private Eye. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-003357-2.

- Lockyer, Sharon. (2006) "A two-pronged? Exploring Private Eye's satirical humour and investigative reporting." Journalism Studies 7.5 (2006): 765–781.

- Macqueen, Adam (2011). Private Eye: The First 50 Years– An A–Z. London: Private Eye Productions. ISBN 978-1-901784-56-5.

- Marnham, Patrick (1982). The Private Eye Story. Andre Deutsch/Private Eye. ISBN 0-233-97509-8.

- Wilmut, Roger (1980). "The Establishment Club, 'Private Eye', 'That Was The Week That Was'". From fringe to flying circus: celebrating a unique generation of comedy, 1960–1980. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 9780413469502.