History of Nauru

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (April 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| History of Nauru | |

|---|---|

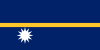

The flag of Nauru reflects the 12 original tribes that inhabited the country | |

| Historical Periods | |

| Pre-history | until 1888 |

| German Rule | 1888–1919 |

| Australia trust | 1920–1967 |

| Japanese Rule | 1942–45 |

| Republic | 1968–present |

| Major Events | |

| Phosphate originally found | 1900 |

| Collapse of phosphate industry | 2002 |

The history of human activity in Nauru, an island country in the Pacific Ocean, began roughly 3,000 years ago when clans settled the island.

Early history

[edit]

Nauru was settled by Micronesians around 3,000 years ago, and there is evidence of possible Polynesian influence.[1] Nauruans subsisted on coconut and pandanus fruit, and engaged in aquaculture by catching juvenile ibija fish, acclimated them to freshwater conditions, and raised them in Buada Lagoon, providing an additional reliable source of food.[2] Traditionally only men were permitted to fish on the reef, and did so from canoes or by using trained man-of-war hawks.

There were traditionally 12 clans or tribes on Nauru, which are represented in the 12-pointed star in the nation's flag. Nauruans traced their descent on the female side. The first Europeans to encounter the island were on the British whaling ship Hunter, in 1798. When the ship approached, "many canoes ventured out to meet the ship. The Hunter's crew did not leave the ship nor did Nauruans board, but Captain John Fearn's positive impression of the island and its people" led to its English name, Pleasant Island.[3] This name was used until Germany annexed the island 90 years later.

From around 1830, Nauruans had contact with Europeans from whaling ships and traders who replenished their supplies (such as fresh water) at Nauru.[4] The islanders traded food for alcoholic toddy and firearms. The first Europeans to live on the island, starting perhaps in 1830, were Patrick Burke and John Jones, Irish convicts who had escaped from Norfolk Island, according to Paradise for Sale.[5] Jones became "Nauru's first and last dictator," who killed or banished several other beachcombers who arrived later, until the Nauruans banished Jones from the island in 1841.[6]

The introduction of firearms and alcohol destroyed the peaceful coexistence of the 12 tribes living on the island. A 10-year internal war began in 1878 and resulted in a reduction of the population from 1,400 (1843) to around 900 (1888).[7] Ultimately, alcohol was banned and some arms were confiscated.

German protectorate

[edit]

In 1886 Germany was granted the island under the Anglo-German Declaration. The island was annexed by Germany in 1888 and incorporated into Germany's New Guinea Protectorate. Nauru was occupied on 16 April 1888 by German troops, which ended the Nauruan Civil War. On 1 October 1888 the German gunboat SMS Eber landed 36 men on Nauru.[8] Accompanied by William Harris the German marines marched around the island and returned with the twelve chiefs, the white settlers and a Gilbertese missionary.[8] The chiefs were kept under house arrest until the morning of 2 October, when the annexation ceremony began with the raising of the German flag.[8] The Germans told the chiefs that they had to surrender all weapons and ammunition within 24 hours or the chiefs would be taken prisoner.[8] By the morning of 3 October 765 guns and 1,000 rounds of ammunition had been turned over.[8] The Germans called the island Nawodo or Onawero. The arrival of the Germans ended the war, and social changes brought about by the war established kings as rulers of the island, the most widely known being King Auweyida. Christian missionaries from the Gilbert Islands also arrived in 1888.[9] The Germans ruled Nauru for almost three decades. Robert Rasch, a German trader who married a native woman, was the first administrator, appointed in 1888.

At the time there were twelve tribes on Nauru: Deiboe, Eamwidamit, Eamwidara, Eamwit, Eamgum, Eano, Emeo, Eoraru, Irutsi, Iruwa, Iwi and Ranibok. Today the twelve tribes are represented by the twelve-pointed star in the flag of Nauru.

Phosphate was discovered on Nauru in 1900 by the prospector Albert Ellis.[10] The Pacific Phosphate Company started to exploit the reserves in 1906 by agreement with Germany. The company exported its first shipment in 1907.[11][12]

World War I to World War II

[edit]In 1914, following the outbreak of World War I, Nauru was captured by Australian troops, after which Britain held control until 1920. Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom signed the Nauru Island Agreement in 1919, creating a board known as the British Phosphate Commission (BPC). This took over the rights to phosphate mining.[13] According to the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics (now the Australian Bureau of Statistics), "In common with other natives, the islanders are very susceptible to tuberculosis and influenza, and in 1921 an influenza epidemic caused the deaths of 230 islanders." In 1923, the League of Nations gave Australia a trustee mandate over Nauru, with the United Kingdom and New Zealand as co-trustees.[14][15] In 1932, the first Angam Baby was born.

World War II

[edit]

During World War II, Nauru was subject to significant damage from both Axis (German and Japanese) and Allied forces.

On 6 and 7 December 1940 the Nazi German auxiliary cruisers Orion and Komet sank four merchant ships. On the next day, Komet shelled Nauru's phosphate mining areas, oil storage depots, and the shiploading cantilever.[16] The attacks seriously disrupted phosphate supplies to Australia and New Zealand (mostly used for munition and fertiliser purposes.)[17]

Japanese troops occupied Nauru on 26 August 1942,[18] and executed 7 Europeans.[19] The native Nauruans were badly treated by the occupying forces. On one occasion thirty nine people with leprosy were reputedly loaded onto boats which were towed out to sea and sunk. The Japanese troops built 2 airfields on Nauru which were bombed for the first time on 25 March 1943, preventing food supplies from being flown to Nauru.[20] In 1943 the Japanese deported 1,200 Nauruans to work as labourers in the Chuuk islands.[17]

Nauru was finally set free from the Japanese on 13 September 1945, when Captain Soeda, the commander of all the Japanese troops on Nauru, surrendered the island to the Royal Australian Navy and Army. This surrender was accepted by Brigadier J. R. Stevenson, who represented Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee, the commander of the First Australian Army, on board the warship HMAS Diamantina[21][19] Arrangements were made to repatriate from Chuuk the 745 Nauruans who survived Japanese captivity there.[22] They were returned to Nauru by the BPC ship Trienza on 1 January 1946.[23]

Trust Territory

[edit]In 1947,[citation needed] a trusteeship was established by the United Nations, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom became the U.N. trustees of the island, although practical administration was mostly handled by Australia. By 1965 the population reached 5,561, of which just under half were considered Nauruan.[24] In July 1966 the Nauruan Head Chief spoke at the United Nations Trusteeship Council, calling for independence by 31 January 1968. This was supported by the General Assembly in December of that year.[24][25] Australia and the other administering powers sought to arrange an alternative to independence, such as internal self-government similar to that of the West Indies Associated States, or with Australia retaining a role in foreign affairs. Under these envisioned solutions, the resulting political settlement would be permanent, with no route to independence. This was due to concern over implications for other Pacific territories, and for the implication of such a small community (the size of an "English village") gaining the full trappings of statehood. These suggestions were however rejected by Nauru, and Australia was concerned that even if they were accepted by Nauru, they might not be accepted by the UN. In June 1967 it was agreed that assets belonging to the British Phosphate Commission on the island would be sold to Nauru for 21 million Australian dollars. Nauru was granted unconditional independence on 31 January 1968.[24]

Independence

[edit]Nauru became self-governing in January 1966. On 31 January 1968, following a two-year constitutional convention, Nauru became the world's smallest independent republic. It was led by founding president Hammer DeRoburt. In 1967, the people of Nauru purchased the assets of the British Phosphate Commissioners, and in June 1970, control passed to the locally owned Nauru Phosphate Corporation. Money gained from the exploitation of phosphate was put into the Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust and gave Nauruans the second highest GDP Per Capita (second only to the United Arab Emirates) and one of the highest standards of living in the Third World.[26][27]

In 1989, Nauru took legal actions against Australia in the International Court of Justice over Australia's actions during its administration of Nauru. In particular, Nauru made a legal complaint against Australia's failure to remedy the environmental damage caused by phosphate mining.[28] Certain Phosphate Lands: Nauru v. Australia led to an out-of-court settlement to rehabilitate the mined-out areas of Nauru.

By the close of the twentieth century, the finite phosphate supplies were fast running out. Nauru finally joined the UN in 1999.

Modern-day Nauru

[edit]As its phosphate stores began to run out (by 2006, its reserves were exhausted), the island was reduced to an environmental wasteland. Nauru appealed to the International Court of Justice to compensate for the damage from almost a century of phosphate strip-mining by foreign companies. In 1993, Australia offered Nauru an out-of-court settlement of A$2.5 million annually for 20 years. New Zealand and the UK additionally agreed to pay a one-time settlement of $12 million each.[29] Declining phosphate prices, the high cost of maintaining an international airline, and the government's financial mismanagement combined to make the economy collapse in the late 1990s. By the new millennium, Nauru was virtually bankrupt.[30]

In December 1999, four major United States banks banned dollar transactions with four Pacific island states, including Nauru. The United States Department of State issued a report identifying Nauru as a major money laundering centre, used by narcotics traffickers and Russian organized crime figures.

President Bernard Dowiyogo took office in April 2000 for his fourth and, after a minimal hiatus, fifth stints as Nauru's top executive. Dowiyogo first served as president from 1976 to 1978. He returned to that office in 1989, and was re-elected in 1992. A vote in parliament, however, forced him to yield power to Kinza Clodumar in 1995. Dowiyogo regained the presidency when the Clodumar government fell in mid-1998.

In 2001, Nauru was brought to world attention by the Tampa affair, a Norwegian cargo ship at the centre of a diplomatic dispute between Australia, Norway and Indonesia. The ship carried asylum seekers, hailing primarily from Afghanistan, who were rescued while attempting to reach Australia. After much debate many of the immigrants were transported to Nauru, an arrangement known in Australia as the "Pacific Solution". Shortly thereafter, the Nauruan government closed its borders to most international visitors, preventing outside observers from monitoring the refugees' condition.[citation needed]

In December 2003, several dozen of these refugees, in protest of the conditions of their detention on Nauru, began a hunger strike.[31] The hunger strike was concluded in early January 2004 when an Australian medical team agreed to visit the island. Since then, according to recent reports, all but two of the refugees have been allowed into Australia.

During 2002 Nauru severed diplomatic recognition with Taiwan (Republic of China) and signed an agreement to establish diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China. This move followed China's promise to provide more than U.S. $130 million in aid. In 2004, Nauru broke off relations with the PRC and re-established them with the ROC.

Nauru was also approached by the U.S. with a deal to modernize Nauru's infrastructure in exchange for suppression of the island's lax banking laws that allow activities that are illegal in other countries to flourish. Under this deal, allegedly, Nauru would also establish an embassy in China and perform certain "safehouse" and courier services for the U.S. government, in a scheme codenamed "Operation Weasel". Nauru agreed to the deal and instituted banking reform, but the U.S. later denied knowledge of the deal. The matter is being pursued in an Australian court, and initial judgments have been in favor of Nauru.

The government is desperately in need of money to pay off salary arrears of civil servants and to continue funding the welfare state built up in the heyday of phosphate mining (Nauruans pay no taxes).[32] Nauru has yet to develop a plan to remove the innumerable coral pinnacles created by mining and make those lands suitable for human habitation.[29]

Following parliamentary elections in 2013, Baron Waqa was elected president. He held the presidential title six years from 2013 to 2019. President Waqa was a strong supporter of Australia keeping refugees in a refugee camp on Nauru soil. The incumbent president lost his parliamentary seat in 2019 Nauruan parliamentary election, meaning he lost his bid for re-election.[33][34] In August 2019 the parliament elected former human rights lawyer Lionel Aingimea as the new President of Nauru.[35] Following the 2022 Nauruan parliamentary election, Russ Kun was elected president to succeed Aingimea.[36] On 30 October 2023, David Ranibok Adeang was elected President of the Republic of Nauru.[37]

See also

[edit]- Nauruan Civil War

- Angam Day

- Japanese occupation of Nauru

- History of Oceania

- President of Nauru

- List of colonial governors of Nauru

- Nauru Phosphate Corporation

- Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust

- Politics of Nauru

- 1948 Nauru riots

References

[edit]- ^ Nauru Department of Economic Development and Environment. 2003. First National Report To the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) Retrieved 2006-05-03 Archived 14 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McDaniel, C. N.; Gowdy, J. M. (2000). Paradise for Sale. University of California Press. pp. 13–28. ISBN 0-520-22229-6.

- ^ McDaniel, C. N. and Gowdy, J. M. 2000. Paradise for Sale. University of California Press ISBN 978-0-520-22229-8 pp 29-30

- ^ Ellis, Albert F. (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru; Their Story. Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson, limited. p. 29. OCLC 3444055.

- ^ McDaniel, C. N. and Gowdy, J. M. 2000. Paradise for Sale. University of California Press ISBN 978-0-520-22229-8 pp 30

- ^ McDaniel, C. N. and Gowdy, J. M. 2000. Paradise for Sale. University of California Press ISBN 978-0-520-22229-8 pp 31

- ^ "Background Note: Nauru". U.S. Department of State. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Carl N. McDaniel, John M. Gowdy: Paradise for Sale: A Parable of Nature, University of California Press, 2000, ISBN 0520222296, page 35.

- ^ Ellis, A. F. 1935. Ocean Island and Nauru - their story. Angus and Robertson Limited. pp 29-39

- ^ Ellis, Albert F. (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru; Their Story. Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson, limited. OCLC 3444055.

- ^ Ellis, A. F. 1935. Ocean Island and Nauru - their story. Angus and Robertson Limited. pp 127–139

- ^ Maslyn Williams & Barrie Macdonald (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-522-84302-6.

- ^ Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia No. 35 - 1942 and 1943. Austràlia Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics (now Australian Bureau of Statistics).

- ^ Cain, Timothy M., comp. "Nauru." The Book of Rule. 1st ed. 1 vols. New York: DK Inc., 2004.

- ^ "Agreement (between Australia, New Zealand and United Kingdom) regarding Nauru". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "How Nauru Took the Shelling". XI(7) Pacific Islands Monthly. 14 February 1941. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ a b Haden, J. D. 2000. Nauru: a middle ground in World War II Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Pacific Magazine Retrieved 5 May 2006

- ^ Lundstrom, John B., The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, Naval Institute Press, 1994, p. 175.

- ^ a b "Nauru Officials Murdered By Japs". XVI(3) Pacific Islands Monthly. 16 October 1945. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Interesting Sidelights on Jap Occupation of Nauru". XVI(11) Pacific Islands Monthly. 18 June 1946. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ The Times, 14 September 1945

- ^ "Only 745 Returned". XX(10) Pacific Islands Monthly. 1 May 1950. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Garrett, J. 1996. Island Exiles. ABC. ISBN 0-7333-0485-0. pp176–181

- ^ a b c Brij V Lal (22 September 2006). "'Pacific Island talks': Commonwealth Office notes on four-power talks in Washington". British Documents on the End of Empire Project Series B Volume 10: Fiji. University of London: Institute of Commonwealth Studies. pp. 299, 309. ISBN 9780112905899.

- ^ "Question of the Trust Territory of Nauru" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 20 December 1966. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Nauru seeks to regain lost fortunes Nick Squires, 15 March 2008, BBC News Online. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Tiny Pacific Isle's Citizens Rich, Fat and Happy--Thanks to the Birds". Los Angeles Times. 31 March 1985. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Certain Phosphate Lands: Nauru v. Australia". The American Journal of International Law. 87: 282–288. doi:10.2307/2203821. JSTOR 2203821. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Ali, Saleem H. (14 July 2016). "The new rise of Nauru: can the island bounce back from its mining boom and bust?". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Shenon, Philip (10 December 1995). "A Pacific Island Nation Is Stripped of Everything". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Hazara asylum seekers hunger strike on Nauru, 2003-2004". The Commons. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Trumbull, Robert (7 March 1982). "World's Richest Little Isle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Nauru President Baron Waqa loses election | DW | 25.08.2019". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "Nauru's President ousted during national election". ABC News. 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Former human rights lawyer Lionel Aingimea becomes Nauru leader". ABC News. 27 August 2019.

- ^ "Hopes for change as Russ Kun elected as Nauru's president". ABC Pacific. 28 September 2022.

- ^ "The Government of the Republic of Nauru - The Government of the Republic of Nauru". www.nauru.gov.nr.

Further reading

[edit]- Storr, C. (2020). International Status in the Shadow of Empire: Nauru and the Histories of International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fabricius, Wilhelm (1992). Nauru 1888-1900. ed. and trans. Dymphana Clark and Stewart Firth. Canberra: Australian National University. ISBN 0-7315-1367-3.

- Williams, Maslyn & Macdonald, Barrie (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84302-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)