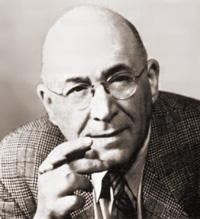

Mario Pei

Mario Pei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 16, 1901 Rome, Italy |

| Died | March 2, 1978 (aged 77) Glen Ridge, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Known for | Popular linguistics |

Mario Andrew Pei (February 16, 1901 – March 2, 1978) was an Italian-born American linguist and polyglot who wrote a number of popular books known for their accessibility to readers without a professional background in linguistics. His book The Story of Language (1949) was acclaimed for its presentation of technical linguistics concepts in ways that were entertaining and accessible to a general audience.[1]

Pei was a supporter of uniting humans under one language, and in 1958 published a book entitled One Language For the World and How to Achieve It and sent a copy to the leader of every nation in existence at the time. The book argued that the United Nations should select one language—regardless of whether it was an existing natural language like English or a constructed language like Esperanto—and require it to be taught as a second language to every schoolchild in the world.[1]

Life and career[edit]

Pei was born in Rome, Italy, and emigrated to the United States with his mother in order to join his father in April 1908. By the time that he was out of high school, he spoke not only English and his native Italian but also French and had studied Latin as well. Over the years, he became fluent in several other languages (including Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, and German) capable of speaking some thirty others, having become acquainted with the structure of at least one hundred of the world's languages.

In 1923, he began his career teaching languages at City College of New York, and in 1928 he published his translation of Vittorio Ermete de Fiori's Mussolini: The Man of Destiny. Pei received a PhD from Columbia University in 1937, focusing on Sanskrit, Old Church Slavonic, and Old French.[2]

That year, he joined the Department of Romance Languages at Columbia University, becoming a full professor in 1952. In 1941, he published his first language book, The Italian Language. His facility with languages was in demand in World War II, and Pei served as a language consultant with two agencies of the Department of War.[citation needed] In this role, he wrote language textbooks, developed language courses, and wrote language guidebooks.

While working as a professor of Romance Philology at Columbia University, Pei wrote over 50 books, including the best-sellers The Story of Language (1949) and The Story of English (1952). His other books included Languages for War and Peace (1943; later retitled The World's Chief Languages), A Dictionary of Linguistics (written with Frank Gaynor, 1954), All About Language (1954), Invitation to Linguistics: A Basic Introduction to the Science of Language (1965), and Weasel Words: Saying What You Don't Mean (1978).

Pei wrote The America We Lost: The Concerns of a Conservative (1968), a book advocating individualism and constitutional literalism. In the book, Pei denounces the income tax as well as communism and other forms of collectivism.

Pei was also an internationalist and advocated the introduction of Esperanto into school curricula across the world to supplement local languages.

He died on March 2, 1978. Arrangements were made with George Van Tassel's Community Funeral Home in Bloomfield, N.J., and burial at St. Raymond's Cemetery in the Bronx followed.

Pei and Esperanto[edit]

Pei was fond of Esperanto, an international auxiliary language. He wrote his positive views on it in his book called One Language for the World. He also wrote a 21-page pamphlet entirely on world language and Esperanto called Wanted: a World Language.

Quotes[edit]

Value of neologisms[edit]

Noting that neologisms are of immense value to the continued existence of a living language, as most words are developed as neologisms from root words, Pei stated in The Story of Language:

Of all the words that exist in any language only a bare minority are pure, unadulterated, original roots. The majority are "coined" words, forms that have been in one way or another created, augmented, cut down, combined, and recombined to convey new needed meanings. The language mint is more than a mint; it is a great manufacturing center, where all sorts of productive activities go on unceasingly.[3]

Creative innovation and slang[edit]

While slang may be condemned by purists and schoolteachers, it should be remembered that it is a monument to the language's force of growth by creative innovation, a living example of the democratic, normally anonymous process of language change, and the chief means whereby all the languages spoken today have evolved from earlier tongues.[3]

Works[edit]

Language[edit]

|

Discography[edit]

|

Other[edit]

- The American road to peace: a constitution for the world, 1945, S.F. Vanni

- Introduction to Ada Boni, Talisman Italian Cookbook. 1950. Crown Publishers

- Swords of Anjou, 1953, John Day Company. Pei's first and only novel, praised in HISPANICA [1953] as "an admirable combination of absorbing narrative and sound scholarship ..."

- THE CONSUMER'S MANIFESTO: A Bill Of Rights to Protect the Consumer in the Wars Between Capital and Labor, 1960, Crown Publishers

- Our National Heritage, 1965, Houghton Mifflin

- America We Lost: The Concerns of a Conservative, 1968, World Publishing

- Tales of the natural and supernatural,, 1971, Devin-Adair

See also[edit]

- Remarks on the Esperanto Symposium

- Mario Pei On Esperanto Education

- One Language For The World

- Pei Discography at Smithsonian Folkways

Notes[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Saxon, Wolfgang (5 March 1978). "Mario Andrew Pei, Linguist, Dies at 77". The New York Times. p. 36.

- ^ "Mario Pei | American linguist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b WordSpy Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine