Taksin

| |

|---|---|

| King of Thonburi | |

Statue of Taksin the Great at Hat-Sung Palace (Wat Khung Taphao), Uttaradit province | |

| King of Siam | |

| Reign | 28 December 1768 – 1 April 1782[1][2][a] |

| Coronation | 28 December 1768 |

| Predecessor | Ekkathat (as King of Ayutthaya) |

| Successor | Phutthayotfachulalok (Rama I) (as King of Rattanakosin) |

| Viceroy | Inthraphithak |

| Born | Dên Chao/Sin (Zheng Zhao) 17 April 1734 Ayutthaya, Ayutthaya |

| Died | 7 April 1782 (aged 47)[b] Bangkok, Siam |

| Burial | Wat Intharam, Bangkok |

| Spouse | Batboricha |

| Issue | 21 sons and 9 daughters,[4] including: |

| House | Thonburi dynasty |

| Father | Yong Saetae (Zheng Yong)[5] |

| Mother | Nok-lang (later Princess Phithak Thephamat) |

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism |

King Taksin the Great (Thai: สมเด็จพระเจ้าตากสินมหาราช, RTGS: Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharat,[c] ) or the King of Thonburi (Thai: สมเด็จพระเจ้ากรุงธนบุรี, RTGS: Somdet Phra Chao Krung Thon Buri;[d] simplified Chinese: 郑昭; traditional Chinese: 鄭昭; pinyin: Zhèng Zhāo; Teochew: Dên Chao;[6] 17 April 1734 – 7 April 1782) was the only king of the Thonburi Kingdom that ruled Thailand from 1767 to 1782. He had been an aristocrat in the Ayutthaya Kingdom and then was a major leader during the liberation of Siam from Burmese occupation after the Second Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, and the subsequent unification of Siam after it fell under various warlords. He established the city of Thonburi as the new capital, as the city of Ayutthaya had been almost completely destroyed by the invaders. His reign was characterized by numerous wars; he fought to repel new Burmese invasions and to subjugate the northern Thai kingdom of Lanna, the Laotian principalities, and threatening Cambodia.

Although warfare occupied most of Taksin's reign, he paid a great deal of attention to politics, administration, economy, and the welfare of the country. He promoted trade and fostered relations with foreign countries. He had roads built and canals dug. Apart from restoring and renovating temples, the king attempted to revive literature, and various branches of the arts such as drama, painting, architecture and handicrafts. He also issued regulations for the collection and arrangement of various texts to promote education and religious studies.

He was taken in a coup d'état and executed, and succeeded by his long-time friend Maha Ksatriyaseuk, who then assumed the throne, founding the Rattanakosin Kingdom and the Chakri dynasty, which has since ruled Thailand. In recognition for his deeds, he was later awarded the title of Maharaj (The Great).

Early life

[edit]Ancestry

[edit]

Taksin was born on 17 April 1734, in Ayutthaya.[clarification needed] Taksin had Chinese Teochew, Tai-Chinese and Mon ancestry. His father, Yong Saetae (Thai: หยง แซ่แต้; Chinese: 鄭鏞 Zhèng Yōng), who worked as a tax-collector,[7] was of ethnic Teochew descent from Chenghai District, Shantou, Guangdong, China.[5][8]

His mother, Nokiang (Thai: นกเอี้ยง), was of Mon-Tai descent[9] (and was later appointed to establish the royal title of the Princess Mother Thephamat).[10] Nokiang's mother was a Mon noblewoman who was a younger sister to Phraya Phetburi (personal name: Roeang) and Phraya Ram Chaturon (personal name: Chuan). Phraya Phetburi (Roeang) was governor of Phetburi, then the Mon population center and royal naval base in King Boromakot's reign. Phraya Ram Chaturon (Chuan) served as chief of Siam's Mon community during the reign of King Ekkathat. Nokiang's father was a Tai commoner.[9][11]

Childhood

[edit]Impressed by the boy, Mut, the Chaophraya Chakri who was the Grand Chancellor of Civil Affairs (Thai: สมุหนายก, RTGS: Samuhanayok) in King Boromakot's reign, adopted him and gave him the Thai name Sin (สิน) meaning money or treasure.[12] When he was seven, Sin was assigned to a monk named Thongdi to begin his education in a Buddhist monastery called Kosawat Temple (Thai: วัดโกษาวาส) (later, Choengtha Temple (Thai: วัดเชิงท่า)).[13] After seven years, he was sent by his stepfather to serve as a royal page. He studied Hokkien-Chinese, Vietnamese, and several Indian languages, and became fluent in them. It was the time he learnt Vietnamese, he took his name as "Trịnh Quốc Anh". When Sin and his friend Thongduang who was also a descendant of Mon aristocratic family were Buddhist novices, they reportedly met a Chinese fortune-teller who told them that both had lucky lines in their hands and would both become kings. Neither took it seriously, but Thongduang would become the successor of King Taksin, called Rama I.[14]

Early career

[edit]

After taking the vows of a Buddhist monk for about three years, Sin joined the service of King Ekkathat and was first deputy governor and later governor of Tak,[15] which gained him his name Phraya Tak, the governor of Tak.

In 1765, when the Burmese attacked Ayutthaya, Phraya Taksin defended the capital, for which he was given the title Phraya Wachiraprakan of Kamphaeng Phet. However, he did not have a chance to govern Kamphaeng Phet because the country was in a dire situation. For more than a year, Thai and Burmese soldiers fought fierce battles at the Siege of Ayutthaya. It was during this time that Phraya Vajiraprakarn experienced the setbacks which led him to doubt the value of his endeavors.[citation needed]

Resistance and independence

[edit]

On 3 January 1767, 3 months before the fall of Ayutthaya,[16] Taksin made his way out of the city at the head of 500 followers to Rayong, on the east coast of the Gulf of Thailand.[17] This action was never adequately explained, as the royal compound and Ayutthaya proper was on an island. How Taksin and his followers fought their way out of the Burmese encirclement remains a mystery. He travelled first to Chonburi, a town on the Gulf of Thailand's eastern coast, and then to Rayong, where he raised a small army and his supporters began to address him as Prince Tak.[18] He planned to attack and capture Chanthaburi, according to a popular version of oral history, he said, "We are going to attack Chanthaburi tonight. Destroy all the food and utensils we have, for we will have our food in Chanthaburi tomorrow morning."[19]

On 7 April 1767, Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese. After the destruction of Ayutthaya and the death of the Thai king, the country was split into six parts, with Taksin controlling the east coast. Together with Thongduang, now Chao Phraya Chakri, he eventually managed to drive back the Burmese, defeat his rivals and reunify the country.[20]

With his soldiers he moved to Chanthaburi, and being rebuffed by the governor of the town, he made a surprise night attack on it and captured it on 15 June 1767, only two months after the sack of Ayutthaya.[21] His army was rapidly increasing in numbers, as men of Chanthaburi and Trat, which had not been plundered and depopulated by the Burmese,[22] naturally constituted a suitable base for him to make preparations for the liberation of his motherland.[23]

Having thoroughly looted Ayutthaya, the Burmese did not seem to show serious interest in holding the capital of Siam, since they left only a handful of troops under General Suki to control the shattered city. They turned their attention to the north of their own country which was soon threatened with Chinese invasion. On 6 November 1767, having amassed 5,000 troops and built 100 ships, Taksin sailed up the Chao Phraya River and seized Thonburi opposite present day Bangkok. He executed the puppet Thai governor, Thong-in, whom the Burmese had placed in charge.[24] The taking of Thonburi was quite easy due to the garrison being Thai.[25] He followed up his victory quickly by attacking the main Burmese camp numbering 3,000 men, led by General Suki (สุกี้) at the Battle of Pho Sam Ton (Thai: โพธิ์สามต้น) near Ayutthaya.[26] The Burmese were defeated, General Suki was killed in the fighting, and Taksin won back Ayutthaya from the enemy within seven months of its destruction.[23]

Establishment of the capital

[edit]

King Taksin took important steps to show that he was a worthy successor to the throne. He ensured appropriate treatment to the remnants of the ex-royal family, arranged a grand cremation of the remains of the former ruler Ekkathat, and tackled the problem of establishing the capital.[28] Taksin likely realized that the city of Ayutthaya had suffered such destruction that to restore it to its former state would have strained his resources. The Burmese were quite familiar with Ayutthaya's vulnerabilities, and in the event of renewal of a Burmese attack on it, the troops under the liberator would be inadequate for effective defense of the city. With these considerations in mind, he established his capital at Thonburi, which was closer to the sea.[29] Not only would Thonburi be difficult to invade by land, it would also prevent an acquisition of weapons and military supplies by anyone ambitious enough to establish himself as an independent prince further up the Chao Phraya River.[21] As Thonburi was a small town, Taksin's available forces, both soldiers and sailors, could man its fortifications, and if he found it impossible to hold it against an enemy attack, he could embark the troops and retreat to Chanthaburi.[30]

His successes against competitors for power were due to Taksin's abilities as a warrior, his leadership, valor, and effective organization of his forces. Usually he put himself in the front rank in an encounter with the enemy, thus inspiring his men. Among the officials who cast their fate with him during the campaigns for independence and for the elimination of the self-appointed local nobles were two personalities who subsequently played important roles in Thai history. They were the sons of an official bearing the title of Phra Acksonsuntornsmiantra (Thai: พระอักษรสุนทรเสมียนตรา). The elder son was named Thongduang (Thai: ทองด้วง). He was born in 1737 in Ayutthaya and later was to be the founder of the Chakri Dynasty, while the younger one, Bunma (Thai: บุญมา), born six years later, served as his deputy.[31]

Thongduang, prior to the sacking of Ayutthaya, was ennobled as Luang Yokkrabat, taking charge of royal surveillance, serving the Governor of Ratchaburi, and Bunma had a court title conferred upon him as Nai Sudchinda. Luang Yokkrabat (Thongduang) was therefore not in Ayutthaya to witness the fall of the city, while Nai Sudchinda (Bunma) made his escape from Ayutthaya. However, while King Taksin was assembling his forces at Chanthaburi, Nai Sudchinda brought his retainers to join him, thus helping to increase his fighting strength. Due to his previous acquaintance with him, the liberator was so pleased that he promoted him to be Phra Mahamontri. Just after his coronation, Taksin secured the service of Luang Yokkrabut on the recommendation of Phra Mahamontri (Thai: พระมหามนตรี) and as he was equally familiar with him as with his brother, he raised him to be Phra Rajwarin. Having rendered service to the king during his campaigns or their own expeditions against the enemies, Phra Rajwarin (Thai: พระราชวรินทร์) and Phra Mahamontri rose so quickly in the noble ranks that a few years after, the former was created Chao Phraya Chakri, the rank of the chancellor, while the latter became Chao Phraya Surasi.[29]

Reign

[edit]Accession to the throne

[edit]

On 28 December 1767, Taksin was crowned King of Siam at Thonburi Palace in Thonburi ("Krung Thonburi Sri Maha Samut"), the new capital of Siam, yet had Siam official documents still used the official name of "Krung Pra Maha Nakhon Sri Ayutthaya".[32] He assumed the official name of "Borommaracha IV" and "Phra Sri Sanphet X", but is known to Thai history as King Taksin, a combination of his popular name, "Phraya Tak", and his first name, "Sin", or the King of Thonburi. At the time of his coronation, he was only 34 years of age. W. A. R. Wood (1924) observed that Taksin's father was Chinese or partly Chinese, and his mother Siamese, and he said, "He believed that even the forces of nature were under his control when he was destined to succeeded, and this faith led him to attempt and achieve tasks which to another man would seem impossible. Like Napoleon III, he was a man of destiny."[33] The king elected not return to Ayutthaya but instead to make his capital at Thonburi, which being only 20 kilometers from the sea, was much better suited to seaborne commerce. He never really had time to build it into a great city,[34] as he was occupied with suppression of internal and external enemies, as well as territorial expansion throughout his reign.[35]

Reunification of Siam

[edit]

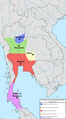

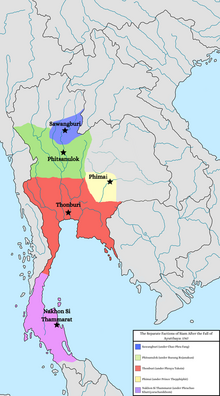

After the sacking of Ayutthaya the country had fallen apart, due to the disappearance of central authority. In addition to Taksin, several local lords had established themselves as rulers in Phimai, Phitsanulok, Fang (Sawangkhaburi, near Uttaradit), and Nakhon Si Thammarat. From 1768 to 1771, Taksin launched campaigns to subjugate these rivals,[36] and Thonburi emerged as the new center of power within Siam.

Wars with Burma

[edit]During Taksin's reign, Taksin is recorded to have waged 9 campaigns against Burma:

First campaign

[edit]In 1767, Hsinbyushin sent an army of 2,000 men under the command of Maengki Manya (Thai: แมงกี้มารหญ้า), the governor of Tavoy to invade Siam after Taksin as established Thonburi as the capital. The Burmese army advanced to the district of Bang Kung in the province of Samut Songkram to the west of the new capital, but was routed by the Thai king in the Battle of Bang Kung in 1767, which is also the site of Wat Bang Kung. When more Chinese troops invaded Burma, Hsinbyushin was forced to recall most of his troops back to resist the Chinese.

Second campaign

[edit]In 1770, Thado Mindin, the governor of Chiang Mai, attacked Sawankhalok. Thado Mindin was repelled by Phraya Surasi.[37][25]

Third campaign

[edit]Taksin launched campaigns to stabilize the northern frontier with Lanna, whose capital Chiang Mai, under Burmese rule, served as launching bases for Burmese incursions. A prerequisite for the maintenance of peace in that region would therefore be the complete expulsion of the Burmese from Chiang Mai.[38] In 1770, Taksin started his first expedition to capture Chiang Mai, but he was pushed back.[citation needed] In 1771, the Burmese governor of Chiang Mai launched an attack on the city of Phichai, beginning a series of campaigns over Siam's northern cities (Sukhothai[clarification needed], Phitsanulok).

Fourth campaign

[edit]In 1772, after finishing his campaign in Luang Phrabang, Nemyo Thihapate attacked the city of Phichai, but was repelled.

Fifth campaign

[edit]In 1773, Nemyo Thihapate attacked the city of Phichai again. During the siege, a commander named Phraya Phichai fought the Burmese until his sword broke. For that, he was given the epithet, "Phraya Phichai Dap Hak", which translates to "Phraya Phichai with the broken sword".[39]

Sixth campaign

[edit]In 1774, Taksin led an army to attack Chiang Mai for the second time. The city was taken. Lanna, which has been under Burmese rule for over 200 years, has fallen to the Siamese.[40]

Seventh campaign

[edit]

In the same year, Hsinbyushin sent an army of 5,000 men to attack Siam. It was completely surrounded by the Thais at the Battle of Bangkaeo (Thai: ยุทธการที่บางแก้ว) in Ratchaburi. Due to starvation, the Burmese army capitulated to Taksin in 1775. Instead of killing all the men, Taksin paraded the prisoners around to boost the morale of his soldiers.[41][42]

Eighth campaign

[edit]

Undaunted by this defeat, and aiming to retake Chiang Mai, Hsinbyushin tried again to conquer Siam, and in October 1775 the greatest Burmese invasion in the Thonburi period began under Maha Thiha Thura, known in Thai history as Azaewunky. He had distinguished himself as a first rate general in the wars with China and in the suppression of a recent Peguan rising.[44]

The war saw Burmese forces pushing into Siamese territory, capturing cities as south as Phitsanulok before the Siamese were able to push back, finally recapturing Chiang Mai in 1776. The war devastated Siam's northern cities, as well as Chiang Mai itself. Chiang Mai was abandoned, remaining deserted for the next fifteen years.[45] Its remaining inhabitants were transplanted to Lampang, where Kawila was established to rule over Lan Na as a Siamese vassal.

Ninth campaign

[edit]In 1776, the new Burmese king, Singu Min, ordered 6,000 troops to attack Chiang Mai. Phraya Wichienprakarn considered that Chiang Mai did not have many troops to that can protect the city therefore allowing people to migrate down to the city of Sawankhalok. Taksin ordered Maha Sura Singhanat, the governor of Phitsanulok to meet up with Phraya Kawila, the ruler of Lampang to retake Chiang Mai. Chiang Mai was retaken, but due to constant wars, it was heavily devastated and remained abandoned for 15 years until it was rebuilt 15 years later.[46]

Relationship with Cambodia

[edit]Sacking of Vientiane

[edit]

In 1777, the ruler of Champasak, which was at that time an independent principality bordering the eastern frontier of the Thonburi Kingdom, supported the Governor of Nangrong, who had rebelled against the King Taksin. The army under Chao Phraya Chakri was ordered to move against the rebel, who was caught and executed. Having received reinforcements under Chao Phraya Surasi, he advanced to Champasak, where the rulers, Chao O and his deputy, were captured and summarily beheaded. Champasak was conquered by Siam, and as a result of Chao Phraya Chakri's successful campaign Taksin promoted him to Somdej Chao Phraya Mahakasatsuek Piluekmahima Tuknakara Ra-adet (Thai:สมเด็จเจ้าพระยามหากษัตริย์ศึก พิลึกมหึมาทุกนคราระอาเดช) (meaning the supreme Chao Phraya, Great Warrior-King who was so remarkably powerful that every city was afraid of his might)[47]—the highest title of nobility that a commoner could achieve.

In Vientiane, a Minister of State, Pra Woh, had rebelled against the ruling prince and fled to the Champasak territory, where he set himself up at Donmotdang, near the present city of Ubon Ratchathani. He made a formal submission to the Thonburi Kingdom when he annexed Champasak, but after the withdrawal of Taksin army, he was attacked and killed by troops from Vientiane. This action was instantly regarded by King Taksin as a great insult to him, and at his command, Somdej Chao Phraya Mahakasatsuek invaded Vientiane with an army of 20,000 men in 1778. Laos had been separated into the two principalities of Luang Prabang and Vientiane since the beginning of the 18th century. The Prince of Luang Prabang, who was at odds with the Prince of Vientiane, submitted to Siam for his own safety, bringing his men to join Somdej Chao Phraya Mahakasatsuek in besieging Vientiane.[48][clarification needed]

After the siege of Vientiane which took about four months, Thaksin's took Vientiane, sacked the city, and carried off the images of Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang to Thonburi. The Prince of Vientiane managed to escape and went into exile. Thus Luang Prabang and Vientiane became tributary state of the Thonburi Kingdom.[49] Nothing definite is known about the origin of the celebrated Emerald Buddha. It is believed that this image was carved from green jasper by an artist or artists in northern India about two thousand years ago. It was taken to Ceylon and then to Chiang Rai of Lan Na kingdom where it was, in 1434, found intact in a chedi which had been struck by lightning. As an object of great veneration among Thai Buddhists, it had been deposited in monasteries in Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Thonburi, and later Bangkok.[50][51]

Economy, culture, and religion

[edit]

When King Taksin established Thonburi as his capital, people were living in abject poverty, and food and clothing were scarce. The King Taksin was well aware of the plight of his subjects, so in order to legitimize his claim for the kingdom, he made economic problems his priority. He paid high prices for rice from his own money to induce foreign traders to bring in adequate amounts of basic necessities to satisfy the need of the people. He then distributed rice and clothing to all his starving subjects. People who had been dispersed came back to their homes. Normalcy was restored. The economy of the country gradually recovered.[52] Taksin sent three diplomatic envoys to China in 1767. In the first year of his reign, Qing dynasty denied his envoys due to him not being an heir apparent from Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty and the two Princes, Chui and Sisang, were political Asylum seekers in Hà Tiên. Six years later, China recognized Taksin as the legitimate ruler of Siam in 1772.[53][clarification needed]

The record dating from 1777 states: "Important goods from Thailand are amber, gold, colored rocks, gold nuggets, gold dust, semi-precious stones, and hard lead." During this time King Taksin actively encouraged the Chinese to settle in Siam, principally those from Chaoshan,[54] partly with the intention to revive the stagnating economy[55] and upgrading the local workforce.[56] He had to fight almost constantly for most of his reign to maintain the independence of his country. As the economic influence of the immigrant Chinese community grew with time, many aristocrats, whom he took in from the Ayutthaya nobility, began to turn against him for having allied with the Chinese merchants. The opposition was led mainly by the Bunnags, a merchant-aristocratic family of Persian origin, successors of Ayutthaya's minister of Ports and Finance, or Phra Klang[57]

Later, Thonburi ordered some guns from England. Royal letters were exchanged and in 1777 the Viceroy of British Raj Madras, George Stratton, sent a gold scabbard decorated with gems to King Taksin. Thai galleons travelled to Portuguese colony of Surat, in Goa, India. However, formal diplomatic relations were not formed. In 1776, Francis Light of the Kingdom of Great Britain sent 1,400 flintlocks along with other goods as gifts to King Taksin.[58][59][clarification needed]

In 1770, natives of Terengganu and Jakarta presented Taksin with 2,200 shotguns. At that time, the Dutch Republic controlled the Java Islands.[60]

Simultaneously Taksin was deeply engaged in restoring law and order in the kingdom and administering a public welfare programme. Abuses in the Buddhist establishment and among the public were duly rectified and food and clothing and other necessities were distributed to those in need.[29]

Taksin was interested in art, including dance and drama. There is evidence that when he went to suppress the Chao Nakhon Si Thammarat faction in 1769, he brought back Chao Nakhon's female dancers. Together with dancers that he had assembled from other places, they trained and set up a royal troupe in Thonburi on the Ayutthaya model. The king wrote four episodes from the Ramakian for the royal troupe to rehearse and perform.[61][62]

When he went north to suppress the Phra Fang faction, he could see that monks in the north were lax and undisciplined. He invited ecclesiastical dignitaries from the capital to teach those monks and brought them back in line with the main teachings of Buddhism. Even though Taksin had applied himself to reforming the Buddhist religion after its period of decline following the loss of Ayutthaya to Burma, gradually bringing it back to the normalcy it enjoyed during the Ayutthaya kingdom, since his reign was so brief he was not able to do very much.

The administration of the Sangha during the Thonburi period followed the model established in Ayutthaya,[63] and he allowed French missionaries to enter Thailand, and like a previous Thai king, helped them build a church in 1780.

Relationship with the Chinese Empire

[edit]

When Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese in 1767, Thai and Chinese sources mentioned that Taksin, then the lord of Tak, broke the Burmese siege and led his troops to Chantaburi. During those years, Chinese Empire had border conflicts with Konbaung Burma. The Burmese invasion into Siam became the warning for Chinese Empire. Taksin, then, sent a tributary mission to require the royal seal, claiming that the throne of Ayutthaya Kingdom had come to an end. However, his attempt was hindered by Mạc Thiên Tứ (Mo Shilin), the governor of Hà Tiên, whom had thorough knowledge of Chinese diplomatic practices and alleged that Taksin was a usurper.[64][65] Tứ also offered shelter to Prince Chao Chui, an Ayutthaya prince.[66][6][67][65]

The Chinese Court could not help but seize the chance by asking Taksin, as a 'new vassal', to be her ally in the war against the Burmese. Eventually Chinese Court approved the royal status of Taksin as the new king of Siam.

A considerable contribution to his success came from the Teochew Chinese trading community of the region, on whom Taksin was able to call by virtue of his paternal relations; he was half-Teochew himself. In the short run, the Chinese trade provided the foodstuffs and goods needed for the warfare that enabled Taksin to build up his fledgling state. In the long run, it produced income that could be used "to defray the expenses of the state and for the upkeep of the individual royal, noble, and wealthy commercial families."[68]

As one contemporary observed, François Henri Turpin (1771), under the famine conditions of 1767–1768 :

- "Taksin showed his generous spirit. The needy were destitute no longer. The public treasury was opened for the relief. In return for cash, foreigners supplied them with the products that the soil of the country had refused. The Usurper [Taksin] justified his claim [to be king] by his benevolence. Abuses were reformed, the safety of property and persons was restored, but the greatest severity was shown to malefactors. Legal enactments at which no one complained were substituted for the arbitrary power that sooner or later is the cause of rebellions. By the assurance of public peace he was able to consolidate his position and no one who shared in the general prosperity could lay claim to the throne."[69]

A tomb containing Taksin's clothes and a family shrine were found at Chenghai district in Guangdong province in China in 1921. It is believed that a descendant of Taksin must have sent his clothes to be buried there to conform to Chinese practice. This supports the claim that the place was his father's hometown.[70] Chinese people called it "Tomb of King Zhèng" (鄭王墓), or its official name "Cenotaph of Zhèng Xìn" (鄭信衣冠墓). It had been included in the list of Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at Chenghai District (澄海區文物保護單位) since 5 December 1984. Princess Sirindhorn had visited the tomb in 1998. Now the nearby area is opened to the public as Zheng Emperor Taksin Park (鄭皇達信公園).

Final years and death

[edit]

Thai historians indicate that the strain on him took its toll, and the king started to become a religious fanatic. In 1781 Taksin showed increasing signs of mental trouble. He believed himself to be a future Buddha, expecting to change the color of his blood from red to white. As he started practicing meditation, he even gave lectures to the monks. More seriously, he was provoking schism in Siamese Buddhism by requiring that the monkhood should recognize him as a sotāpanna or "stream-winner"—a person who has embarked on the first of the four stages of enlightenment.[71] Monks who refused to bow to Taksin and worship him as god were demoted in status, and hundreds who refused to worship him as such were flogged and sentenced to menial labor.[49]

Economic tension caused by war was serious. As famine spread, looting and crimes were widespread. Corrupt officials were reportedly abundant. According to some sources, many oppressions and abuses made by officials were reported. King Taksin punished them harshly, torturing and executing high officials. Discontent among officials could be expected.

Several historians have suggested that the tale of his 'insanity' may have been reconstructed as an excuse for his overthrow. However, the letters of a French missionary who was in Thonburi at the time support the accounts of the monarch's peculiar behavior which reported that "He (Taksin) passed all his time in prayer, fasting, and meditation, in order by these means to be able to fly through the air." Again, the missionaries describe the situation:

- "For some years, the King of Siam has tremendously vexed his subjects and the foreigners who dwelt in or came to trade in his kingdom. Last year (1781) the Chinese, who were accustomed to trade, found themselves obliged almost to give it up entirely . This past year the vexations caused by this King, more than half-mad, have become more frequent and more cruel than previously. He has had imprisoned, tortured, and flogged, according to his caprice, his wife, his sons faction— even the heir-presumptive, and his high officials. He wanted to make them confess to crimes of which they were innocent."[72]

Thus the terms 'insanity' or 'madness' possibly were the contemporary definition describing the monarch's actions: according to the following Rattanakosin era accounts, King Taksin was described as 'insane.' However, with the Burmese threat still prevalent a strong ruler was needed on the throne.

Finally a faction led by Phraya San (or Phraya San, Phraya Sankhaburi) seized the capital. A coup d'état removing Taksin from the throne consequently took place,[73] Phraya San attacked Thonburi and took control within one night. King Taksin surrendered to the rebels without resistance, and requested to be allowed to join the monkhood in Wat Chaeng (Wat Arun).[74] However, the disturbance in Thonburi widely spread, with killing and looting prevalent. When the coup occurred, General Chao Phraya Chakri was away fighting in Cambodia, but he quickly returned to the Thai capital following being informed of the coup. Upon reaching the capital, the general ended the coup through arrests, investigations and punishments. Peace was then restored in the capital.

According to the Royal Thai Chronicles, General Chao Phraya Chakri decided to put the deposed Taksin to death.[75] Chao Phraya Chakri thought that the king had acted improperly and unjustly, causing great pain for the kingdom; so, it was unavoidable that he be executed.[74] The Chronicles stated that, while being taken to the executing venue, Taksin asked for an audience with General Chao Phraya Chakri, but was turned down by the general. Taksin was beheaded in front of Wichai Prasit fortress on Wednesday, April 10, 1782, and his body was buried at Wat Bang Yi Ruea Tai.[clarification needed] The general then seized control of the capital and declared himself king and establishing the House of Chakri.[75]

An alternative account (by the Official Vietnamese Chronicles) states that Taksin was ordered to be executed in the traditional Siamese way by General Chao Phraya Chakri at Wat Chaeng: by being sealed in a velvet sack and beaten to death with a scented sandalwood club.[76] Another account claimed that Taksin was secretly sent to a palace located in the remote mountains of Nakhon Si Thammarat, where he lived until 1825, and that a substitute was beaten to death in his place.[77] King Taksin's ashes and those of his wife are located at Wat Intharam Worawihan, Thonburi. They have been placed in two lotus bud shaped stupas which stand before the old hall.[78]

Critics of the coup

[edit]It was not clear what role General Chakri played in the coup. Vietnamese royal records reported that King Taksin had some kind of psychosis in his final years; he imprisoned Chakri and Surasi's family. Resentful, the brothers eventually befriended two Vietnamese generals, Nguyễn Hữu Thoại (阮有瑞) and Hồ Văn Lân (胡文璘), the four swearing to help with each other in need. Not long after the coup occurred, Chakri quickly returned to the capital, put down the rebellion, and had Taksin killed. Some Vietnamese sources stated that Taksin was assassinated by General Chakri,[79][80] others that Taksin was sentenced to death and executed in a public place.[81] Phraya San also died during this incident.

Another contradicting view of the events is that General Chakri actually wanted to be king and had accused King Taksin of being Chinese. The late history was aimed at legitimizing the new monarch, Phraya Chakri or Rama I of Rattanakosin. According to Nidhi Eoseewong, a prominent Thai historian, writer, and political commentator, Taksin could be seen as the originator, new style of leader, promoting a 'decentralized' kingdom and new generation of the nobles, of Chinese merchant-origin, his major helpers in the wars.[82] On the other hand, Phraya Chakri and his supporters were of the 'old' generation of the Ayutthaya nobles, discontent with these changes.

However, this overlooks the fact that Chao Phraya Chakri was himself partly of Chinese origin, as well as being married to one of Taksin's daughters. No previous conflicts between them were mentioned in histories. Reports on the conflicts between the king and Chinese merchants were seen as being caused by the control of the price of rice during the time of famine.[83] However, prior to returning to Thonburi, Chao Phraya Chakri had Taksin's son summoned to Cambodia and executed.[84]

Another view of the events is that Thailand owed China millions of baht. In order to cancel the agreement between China and Thailand, King Taksin decided to pretend to be executed.[85]

Legacy

[edit]

King Taksin was seen by some radical[clarification needed] historians as a king who differed from the kings of Ayutthaya, in his origins, his policies, and his leadership style, as a representative of a new class. During the Bangkok Period right up until the Siamese Revolution of 1932, King Taksin was, said,[clarification needed] not as highly honored as other Siamese kings because the leaders in the Chakri Dynasty were still concerned about their own political legitimacy. After 1932, when the absolute monarchy gave way to the democratic period, King Taksin become more honored than ever before, viewed as a national hero. This was because the leaders of that time such as Plaek Phibunsongkhram and even later military junta, on the other hand, wanted to glorify and publicize the stories of certain historical figures in order to support their own policy of nationalism, expansionism and patriotism.

A statue of King Taksin was unveiled in the middle of Wongwian Yai (the Big Traffic Circle) in Thonburi, at the intersection of Prajadhipok/Inthara Phithak/Lat Ya/Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Roads. The king is portrayed with his right hand holding a sword, measuring approximately 9 meters in height from his horse's feet to the spire of his hat, rests on a reinforced concrete pedestal of 8.90 × 1.80 × 3.90 meters. There are four frames of stucco relief on the two sides of the pedestal. The opening ceremony of this monument was held on April 17, 1954, and the royal homage-paying fair takes place annually on December 28. The king today officially comes to pay respect to King Taksin statue.[86]

The monument featuring King Taksin riding on a horseback surrounded by his four trusted soldiers: Pra Chiang-ngen (later Phraya Sukhothai), Luang Pichai-asa (later Phraya Phichai), Luang Prom-sena, Luang Raj-saneha. It is located in Tungnachaey public park on Leap Mueang Road, just opposite the City Hall, Chanthaburi.[87]

In 1981 the Thai cabinet passed a resolution to bestow on King Taksin the honorary title of "the Great". With the intention of glorifying Thai monarchs in history who have been revered and honored with the title "the Great", the Bank of Thailand issued the 12th series of banknotes, called The Great Series, in three denominations: 10, 20 and 100 baht. The monument of King Taksin the Great in Chanthaburi's Tungnachaey recreational park appears on the back of the 20-baht note issued on 28 December 1981.[88] The date of his coronation, December 28, is the official day of homage to King Taksin, although it is not designated as a public holiday. The Maw Sukha Association on January 31, 1999, cast the King Taksin Savior of the Nation Amulet, which sought to honor the contributions of King Taksin to Siam during his reign.[89]

The Na Nagara (also spelled Na Nakorn)[90] family is descended in the direct male line from King Taksin.[91]

King Taksin the Great Shrine is located on Tha Luang Road in front of Camp Taksin. It is an important place of Chantaburi in order to demonstrate binding of People in Chanthaburi to King Taksin. It is a nine-sided building. The roof is a pointed helmet. Inside of this place enshrined the statue of King Taksin.[citation needed]

In addition, Royal Thai Navy has used his name to HTMS Taksin, a modified version of the Chinese-made Type 053 frigate, for glorifying him.

Two hospitals are named after him: Taksin Hospital in Bangkok and Somdejphrajaotaksin Maharaj Hospital in Tak Province.

Titles

[edit]Taksin's Thai full title was Phra Sri Sanphet Somdet Borromthammikkarat Ramathibodi Boromchakraphat Bawornrajabodintr Hariharinthadathibodi Sriwibool Khunruejitr Rittirames Boromthammikkaraja Dechochai Phrommathepadithep Triphuwanathibet Lokachetwisut Makutprathetkata Maha Phutthangkul Boromnartbophit Phra Buddha Chao Yu Hua Na Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Baworn Thavarawadi Sri Ayutthaya Maha Dilokphop Noppharat Ratchathaniburirom Udom Praratchaniwet Maha Sathan (Thai: พระศรีสรรเพชร สมเด็จบรมธรรมิกราชาธิราชรามาธิบดี บรมจักรพรรดิศร บวรราชาบดินทร์ หริหรินทร์ธาดาธิบดี ศรีสุวิบูลย์ คุณรุจิตร ฤทธิราเมศวร บรมธรรมิกราชเดโชชัย พรหมเทพาดิเทพ ตรีภูวนาธิเบศร์ โลกเชษฏวิสุทธิ์ มกุฏประเทศคตา มหาพุทธังกูร บรมนาถบพิตร พระพุทธเจ้าอยู่หัว ณ กรุงเทพมหานคร บวรทวาราวดีศรีอยุธยา มหาดิลกนพรัฐ ราชธานีบุรีรมย์อุดมพระราชนิเวศมหาสถาน)

Issue

[edit]King Taksin had 21 sons and 9 daughters:[4]

|

|

Battle record

[edit]- Siege of Ayutthaya (1766–1767): Defeat

- Battle of Pho Sam Ton (1767): Victory

- Battle of Bang Kung (1767): Victory

- Invasion of the State of Phitsanulok (1768): Defeat

- Invasion of the State of Phimai (1768): Victory

- Invasion of the State of Nakhon Si Thammarat (1769): Victory

- Invasion of the State of Sawangburi (1770): Victory

- Siege of Chiang Mai (1770): Defeat

- Invasion of Hà Tiên (Banteay Mas) (1771): Victory[92]

- Battle of Phichai (1771): Victory

- Siege of Chiang Mai (1771): Defeat

- Battle of Phichai (1773): Victory

- Siege of Chiang Mai (1774): Victory

- Battle of Bangkaeo (1774): Victory

- Siege of Phitsanulok (1775–1776): Defeat

Expansion map

[edit]-

Taksin's domain in 1767

-

Taksin's domain in 1768

-

Taksin's domain in 1769

-

Taksin's domain in 1770

-

Taksin's domain in 1774

-

Taksin's domain in 1777

-

Taksin's domain in 1778

See also

[edit]- List of people with the most children

- Right of conquest

- Monarchy of Thailand

- Thonburi Kingdom

- Wongwian Yai

- 1924 Palace Law of Succession

Notes

[edit]- ^ Accounts vastly differ to when Taksin stepped down from the throne and entered the monkhood, which has been argued to have occurred as early as three months prior to his execution.[3]

- ^ Traditionally accepted date of his execution.

- ^ pronounced [sǒm.dèt pʰráʔ t͡ɕâːw tàːk.sǐn mā.hǎː.râːt].

- ^ pronounced [sǒm.dèt pʰráʔ t͡ɕâːw krūŋ tʰōn bū.rīː].

Citations

[edit]- ^ Terwiel, B. J. (Barend Jan) (1983). A history of modern Thailand, 1767–1942. St. Lucia; New York : University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-1892-7. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ chinese society in thailand: an analytical history. cornell university press. 1957.

- ^ "ว่าด้วยพระเจ้าตาก ตอน 5: สองคน สองประวัติศาสตร์ EP.50". YouTube.

3:41–3:55

- ^ a b ธำรงศักดิ์ อายุวัฒนะ (2001). ราชสกุลจักรีวงศ์ และราชสกุลสมเด็จพระเจ้าตากสินมหาราช (in Thai). Bangkok: สำนักพิมพ์บรรณกิจ. p. 490. ISBN 974-222-648-2.

- ^ a b Lintner, p. 112

- ^ a b Trần Trọng Kim, Việt Nam sử lược, vol. 2, chap. 6

- ^ Parkes, p. 770

- ^ Woodside 1971, p. 8.

- ^ a b Roy, Edward (2010). "Prominent Mon Lineages from Late Ayutthaya to Early Bangkok" (PDF). The Siam Society Under Royal Patronage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2023.

- ^ Wyatt, 140

- ^ Siamese Melting Pot: Ethnic Minorities in the Making of Bangkok. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. 2017. p. 78.

- ^ "RID 1999". RIT. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

Select สิ and enter สิน

- ^ "Wat Choeng Thar's official website". iGetWeb. Archived from the original on 9 November 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ พระราชวรวงศ์เธอ กรมหมื่นพิทยาลงกรณ์. สามกรุง (in Thai). Bangkok: สำนักพิมพ์คลังวิทยา. pp. 54–58.

- ^ Webster, 156

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World (p. 262). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ John Bowman (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 514. ISBN 0-231-11004-9.

- ^ Eoseewong, p. 126

- ^ "King Taksin's shrine". Royal Thai Navy. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Eoseewong, p. 98

- ^ a b Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 385

- ^ "Art&Culture" (in Thai). Crma.ac.th. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ a b W.A.R.Wood, p. 253

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 401–402

- ^ a b "Full page photo" (PDF). Finearts.go.th. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 403

- ^ Jean Vollant des Verquains History of the revolution in Siam in the year 1688, in Smithies 2002, pp. 95–96

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 388

- ^ a b c Syamananda, p. 95

- ^ Sunthorn Phu (2007). Nirat Phra Bart (นิราศพระบาท) (in Thai). Kong Toon (กองทุน). pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-974-482-064-8.

- ^ Prince Chula, p. 74

- ^ "Palaces in Bangkok". Mybangkokholiday.com. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ^ Wood, pp. 253–254

- ^ Wyatt, p. 141

- ^ Syamananda, p. 94

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (p. 307). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารกรุงธนบุรี ฉบับหมอบลัดเล, หน้า 50–53

- ^ Wood, pp. 259–260

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารกรุงธนบุรี ฉบับหมอบลัดเล, หน้า 68

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารกรุงธนบุรี ฉบับหมอบลัดเล, หน้า 68–78

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 462

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารกรุงธนบุรี ฉบับหมอบลัดเล, หน้า

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, Prince (1918). พงษาวดารเรื่องเรารบพม่า ครั้งกรุงธน ฯ แลกรุงเทพ ฯ. Bangkok.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wood, pp. 265–266

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 530

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารกรุงธนบุรี, หน้า 177

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 531–532

- ^ Wood, p. 268

- ^ a b Wyatt, p. 143

- ^ Following the Journey of the Emerald Buddha. Siam Rat Blog Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 534

- ^ (in Thai) Collected History Part 65. Bangkok, 1937, p. 87

- ^ A Short History of China.... Internet Archive. 1996. p. 114. ISBN 978-1566198516. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

King taksin qianlong.

- ^ Lintner, p. 234

- ^ Baker, Phongpaichit, p. 32

- ^ Editors of Time Out, p. 84

- ^ Handley, p. 27

- ^ "The Madras Despatches, 1763–1764" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (2014). Asian Expansions: The Historical Experiences of Polity Expansion in Asia. Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 9781135043537. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "400 years Thai-Dutch Relation: VOC in Judea, Kingdom of Siam". Archived from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Amolwan Kiriwat. Khon:Masked dance drama of the Thai Epic Ramakien Archived April 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ Pattama Wattanapanich: The Study of the characteristics of the court dance drama in the reign of King Taksin the Great, 210 pp.

- ^ Sunthorn Na-rangsi. Administration of the Thai Sangha: past, present and future Archived February 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ Eric Tagliacozzo, Wen-chin Chang, Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia, p. 151

- ^ a b 乾隆实录卷之八百十七 (in Chinese).

- ^ Jiamrattanyoo, Arthit (2011). รัฐศาสตร์สาร ปีที่ 37 ฉบับที่ 2 (พฤษภาคม-สิงหาคม 2559). กรุงเทพฯ: โรงพิมพ์มหาวิทยาลัยธรรมศาสตร์. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-616-7308-25-8.

- ^ Đại Nam liệt truyện tiền biên, vol. 6

- ^ Sarasin Viraphol, Tribute and Profit: Sino–Siamese Trade, 1652–1853 (Cambridge, Mass., 1977), p. 144, citing a writing by King Mongkut, dated 1853, from the Thai National Library.

- ^ François Henri Turpin, History of the Kingdom of Siam, trans. B.O. Cartwright (Bangkok, 1908), pp. 178–179; original French ed., 1771.

- ^ Pimpraphai Pisalbutr (2001). Siam Chinese boat Chinese in Bangkok regend (in Thai). Nanmee Books. p. 93. ISBN 974-472-331-9.

- ^ Craig J. Reynolds (1920). The Buddhist Monkhood in Nineteenth Century Thailand. Cornell University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link), p. 33 - ^ Journal of M. Descourvieres, (Thonburi). Dec. 21, 1782; in Launay, Histoire, p. 309.

- ^ Rough Guides (2000). The Rough Guide to Southeast Asia. Rough Guides. p. 823. ISBN 1-85828-553-4.

- ^ a b Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ a b Nidhi Eoseewong. (1986). Thai politics in the reign of the King of Thon Buri. Bangkok : Arts & Culture Publishing House. pp. 575.

- ^ Prida Sichalalai. (December 1982). "The last year of King Taksin the Great". Arts & Culture Magazine, (3, 2).

- ^ Wyatt, p. 145; Siamese/Thai history and culture – Part 4 Archived August 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "see bottom of the page – item 7". Thailandsworld.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim, Việt Nam sử lược, vol. 2, chap. 8

- ^ Đại Nam chính biên liệt truyện sơ tập, vol. 32

- ^ Trịnh-Hoài-#-Dú'c; Aubaret, Louis Gabriel G. (1864). Gia-dinh-Thung-chi: Histoire et description de la basse Cochinchine (in French). pp. 47–49.

- ^ Nidhi Eoseewong, p. 55

- ^ Hamilton, p. 42

- ^ Syamananda, pp. 98–99

- ^ ทศยศ กระหม่อมแก้ว (2007). พระเจ้าตากฯ สิ้นพระชนม์ที่เมืองนคร (in Thai). Bangkok: สำนักพิมพ์ร่วมด้วยช่วยกัน. p. 176. ISBN 978-974-7303-62-9.

- ^ Donald K. Swearer (2004). Becoming the Buddha: The Ritual of Image. Princeton University Press. p. 235. ISBN 0691114358.

- ^ Sarawasi Mekpaiboon, Sirichoke Lertyaso (in Thai). National Geographic No.77, December 2007. Bangkok : Amarin Printing And Publishing Public Company Limited, p. 57

- ^ Wararat; Sumit (23 February 2012). "The Great Series". Banknotes > History and Series of Banknotes > Banknotes, Series 12. Bank of Thailand. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

20 Baht Back—Notification Date November 2, 1981 Issue Date December 28, 1981

- ^ Swearer, p. 235

- ^ Dickinson, p. 64

- ^ Handley, p. 466

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (pp. 263–264). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

References

[edit]- Anthony Webster (1998). Gentleman Capitalists: British Imperialism in Southeast Asia 1770–1890. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-171-7.

- Bertil Lintner (2003). Blood Brothers: The Criminal Underworld of Asia. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 1-4039-6154-9.

- Carl Parkes (2001). Moon Handbooks: Southeast Asia 4 Ed. Avalon Travel Publishing. ISBN 1-56691-337-3.

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- Chris Baker, Pasuk Phongpaichit (2005). A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81615-7.

- Chula Chakrabongse, Prince. Lords of Life : A History of the Kings of Thailand. Alvin Redman Limited.

- Damrong Rajanubhab, Prince (1920). The Thais Fight the Burmese (in Thai). Matichon. ISBN 978-974-02-0177-9.

- David K. Wyatt (1984). Thailand: A Short History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03582-9.; Siamese/Thai history and culture – Part 4

- Donald K. Swearer (2004). Becoming the Buddha: The Ritual of Image. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11435-8.

- Editors of Time Out (2007). Time Out Bangkok: And Beach Escapes. Time Out. ISBN 978-1-84670-021-7.

- "Fight Against Vietnamese Influence in Cambodia – Tay Son Rebellion in Dai Viet (Vietnam)". The Story of Thailand. Thailandshistoria.se. 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Gary G. Hamilton (2006). Commerce and Capitalism in Chinese Societies. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15704-8.

- K. W. Taylor (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press.

- Kenneth T. So (2017). The Khmer Kings and the History of Cambodia: Book II – 1595 to the Contemporary Period. DatASIA.

- Nidhi Eoseewong (2007). Commerce and Capitalism in Chinese Societies (in Thai). Matichon. ISBN 978-974-02-0177-9.

- Paul M. Handley (2006). The King Never Smiles. London: Country Life. ISBN 0-300-10682-3.

- Prida Sichalalai. (December 1982). "The last year of King Taksin the Great". Arts & Culture Magazine, (3, 2).

- Rong Syamananda (1990). A History of Thailand. Chulalongkorn University. ISBN 974-07-6413-4.

- Thomas J. Barnes (2000). Tay Son: Rebellion in 18th Century Vietnam. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 0-7388-1818-6.[self-published source]

- Wood, W.A.R. (1924). A History of Siam. London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd.

- William B. Dickinson (1966). Editorial Research Reports on World Affairs. Congressional Quarterly.

External links

[edit]- Thai monarchs

- Thonburi Kingdom

- 1734 births

- 1782 deaths

- 18th-century murdered monarchs

- 1782 murders in Asia

- Executed Thai monarchs

- 1760s in Thailand

- 1770s in Thailand

- 1780s in Siam

- People from Chenghai

- Thai people of Mon descent

- Thai people of Chinese descent

- 18th-century monarchs in Asia

- 18th-century Thai people

- 18th-century Thai monarchs

- Deified male monarchs

- Thonburi dynasty

- Founding monarchs