Monmouthshire

Monmouthshire

Sir Fynwy (Welsh) | |

|---|---|

| |

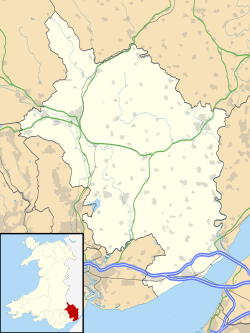

Location within Wales | |

| Coordinates: 51°47′N 2°52′W / 51.783°N 2.867°W | |

| Country | Wales |

| Admin HQ | Usk |

| Largest town | Abergavenny |

| Government | |

| • Type | Principal council |

| • Body | Monmouthshire County Council |

| • Executive | No overall control |

| • Leader | Mary Ann Brocklesbly (L) |

| • MP | Catherine Fookes (L) |

| • MSs | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 850 km2 (330 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 7th |

| Population (2022) | |

| • Total | 93,886 |

| • Rank | 17th |

| • Density | 111/km2 (290/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 15th |

| Ethnicity | |

| • White | 97.5% |

| Welsh language | |

| • Rank | 22nd |

| • Speakers | 8.7%[1] |

| Time zone | GMT |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-MON |

| ONS code | 00PP (ONS) W06000021 (GSS) |

Monmouthshire (/ˈmɒnməθʃər, ˈmʌn-/ MON-məth-shər, MUN-; Welsh: Sir Fynwy) is a county in the south east of Wales. It borders Powys to the north; the English counties of Herefordshire and Gloucestershire to the north and east; the Severn Estuary to the south, and Torfaen, Newport and Blaenau Gwent to the west. The largest town is Abergavenny, and the administrative centre is Usk.

The county is rural, although adjacent to the city of Newport and the urbanised South Wales Valleys; it has an area of 330 square miles (850 km2) and a population of 93,000. After Abergavenny (12,515), the largest towns are Chepstow (12,350), Monmouth (10,508), and Caldicot (9,813). The county has one of the lowest percentages of Welsh speakers in Wales, at 8.2% of the population in 2021.

The lowlands in the centre of Monmouthshire are gently undulating, and shaped by the River Usk and its tributaries. The west of the county is hilly, and the Black Mountains in the northwest are part of the Brecon Beacons National Park (Bannau Brycheiniog). The border with England in the east largely follows the course of the River Wye and its tributary, the River Monnow. In the southeast is the Wye Valley AONB, a hilly region which stretches into England. The county has a shoreline on the Severn Estuary, with crossings into England by the Severn Bridge and Second Severn Crossing.

The name is identical to that of the historic county, of which the current local authority covers the eastern three-fifths. Between 1974 and 1996, the historic county was known as Gwent, recalling the medieval kingdom which covered a similar area. The present county was formed under the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, which came into effect in 1996. In his essay 'Changes in local government', in the fifth and final volume of the Gwent County History, Robert McCloy writes, "the local government of no county in the United Kingdom in the twentieth century was so transformed as that of Monmouthshire".[2]

History

[edit]Pre-History

[edit]

Evidence of human activity in the Mesolithic period has been found across Monmouthshire; examples include important remains on the Caldicot and Wentloog Levels[3][a] and at Monmouth.[5] An important hoard of Bronze Age axes was discovered at St Arvans.[6] The county has a number of hillfort sites, such as those at Bulwark[7] and Llanmelin Wood.[8] The latter has been suggested as the capital of the Silures, a Celtic tribe who occupied south-east Wales in the Iron Age.[9] The Silures proved among the most intractable of Rome's opponents, Tacitus described them as "exceptionally stubborn" and Raymond Howell, in his county history published in 1988, notes that while it took the Romans five years to subdue south-east England, it took thirty-five before complete subjugation of the Silurian territories was achieved.[10]

Roman period

[edit]

The Roman conquest of Britain began in AD 43, and within five years they had reached the borders of what is now Wales.[11] In south-east Wales they encountered strong resistance from the Silures, led by Caratacus (Caradog), who had fled west after the defeat of his own tribe, the Catuvellauni. His final defeat in AD 50 saw his transportation to Rome, but stiff Silurian resistance continued, and the subjugation of the entirety of south-east Wales was not achieved until around AD 75, under the governor of Britain, Sextus Julius Frontinus.[10]

Monmouthshire's most important Roman remains are found at the town of Venta Silurum ("Market of the Silures"), present-day Caerwent in the south of the county. The town was established in AD 75,[12] laid out in the traditional rectangular Roman pattern of twenty insulae with a basilica and a temple flanking a forum.[13] Other Roman settlements in the area included Blestium (Monmouth).[14][b] The Romanisation of Monmouthshire was not without continuing civil unrest; the defences at Caerwent, and at Caerleon, underwent considerable strengthening in the 190s in response to disturbances. The Silurian identity was not extinguished: the establishment of a Respublica Civitatis Silurium (an early town council) in around 300 testifies to the longevity of the indigenous tribal culture.[16]

Sub-Roman period

[edit]The Roman abandonment of Britain from AD 383 saw the division of Wales into a number of petty kingdoms. In the south east (the present county of Monmouthshire) the Kingdom of Gwent was established, traditionally by Caradoc, in the 5th or 6th centuries. Siting their capital at Caerwent, the settlement gave its name to the kingdom.[17] The subsequent history of the area prior to the Norman Conquest is poorly documented and complex. The kingdom of Gwent frequently fought with the neighbouring Welsh kingdoms, and sometimes joined in alliance with them in, generally successful, attempts to repel the Anglo-Saxons, their common enemy. The Book of Llandaff records such a victory over the Saxon invaders achieved by Tewdrig at a battle near Tintern in the late 6th century.[18][c] An example of the alliances formed by neighbouring petty kings was the Kingdom of Morgannwg, a union between Gwent and its western neighbour, the kingdom of Glywysing, which formed and reformed between the 8th and the 10th centuries.[20] The common threat they faced is shown in Offa's Dyke, the physical delineation of a border with Wales created by the Mercian king.[21][d] For a brief period in the 11th century, Monmouthshire, as Gwent, became part of a united Wales under Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, but his death in 1063 was soon followed by that of his opponent Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, and the re-established unity of the country was to come from Norman dominance.[23]

Norman period and Middle Ages

[edit]

The Norman invasion of South Wales from the late 1060s saw the destruction of the Kingdom of Gwent,[24] and its replacement by five Marcher lordships based at Striguil (Chepstow), Monmouth, Abergavenny, Usk and Caerleon.[25] The Marcher Lord of Abergavenny, Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester, described the rule of the lords as sicut regale ("like unto a king").[26] The lords established castles, first earth and wood motte-and-bailey constructions, and later substantial structures in stone, such as Chepstow Castle, begun by William FitzOsbern, 1st Earl of Hereford as early as 1067,[27] and that at Tregrug, near Llangybi, by de Clare's son, Gilbert.[28] In the early Norman period, the cleric and chronicler, Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1095 – c. 1155), who may have been born at Monmouth, wrote his The History of the Kings of Britain, with a focus on King Arthur and Camelot which Geoffrey located at Caerleon (now in Newport), and which remained highly influential for centuries, although modern scholars consider it little more than a literary forgery.[29][e]

Christmas 1175 saw an outbreak of particular violence in the gradual extension of Norman control over South Wales. The Marcher lord William de Braose invited Seisyll ap Dyfnwal, lord of Upper Gwent, and an array of other Welsh notables to a feast at Abergavenny Castle. De Braose proceeded to have his men massacre the Welsh, intending the obliteration of the indigenous Gwent aristocracy, before sending them to burn Seisyll's home at Castell Arnallt and to murder his son. A wave of Welsh retaliation followed, described in detail by the contemporary chronicler, Gerald of Wales.[31]

Monmouthshire's Norman castles later became favoured residences of the Plantagenet nobility. Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster (c. 1310–1361), was reputedly born at Grosmont Castle,[32] home of his father Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, grandson of Henry III. Becoming the richest and among the most powerful lords in England, Grosmont developed the castle as a sumptuous residence, while the village became an important medieval settlement.[33] Henry V (1386–1422) was born at his father's castle at Monmouth in 1386, and his birth, and his most famous military victory, are commemorated in Agincourt Square in the town, and by a statue on the frontage of the Shire Hall which forms the square's centrepiece.[f][38] In Henry V's wars in France, he received strong military support from the archers of Gwent, who were famed for their skill with the Welsh bow. Gerald recorded, "the men of Gwent are more skilled with the bow and arrow than those who come from other parts of Wales".[39][g]

There was a brief reassertion of Welsh autonomy in Monmouthshire during the Glyndŵr rebellion of 1400 to 1415. Seeking to re-establish Welsh independence, the revolt began in the north, but by 1403 Owain Glyndŵr's army was in Monmouthshire, sacking Usk[41] and securing a victory over the English at Craig-y-dorth, near Cwmcarvan. According to the Annals of Owain Glyn Dwr, "there the English were killed for the most part and they were pursued up to the gates of the town" (of Monmouth).[h][42] This was the high water mark of the revolt; heavy defeats in the county followed in 1405, at the Battle of Grosmont, and at the Battle of Pwll Melyn, traditionally located near Usk Castle, where Glyndŵr's brother was killed and his eldest son captured. The chronicler Adam of Usk, a contemporary observer, noted that "from this time onward, Owain's fortunes began to wane in that region."[43]

Monmouthshire 1535–1974

[edit]

Tudor reforms

[edit]The first Tudor king, Henry VII, was born at Pembroke Castle in the west of Wales, and spent some of his childhood in Monmouthshire, at Raglan Castle as a ward of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke.[44] His son and heir Henry VIII was to bring the rule of the Marcher lords to an end. The historic county of Monmouthshire was formed from the Welsh Marches by the Laws in Wales Act 1535. The Laws in Wales Act 1542 enumerated the counties of Wales and omitted Monmouthshire, implying that the county was no longer to be treated as part of Wales. Though for all purposes Wales had become part of the Kingdom of England, and the difference had little practical effect, it did begin a centuries-long dispute as to Monmouthshire's status as a Welsh or as an English county, a debate only finally brought to an end in 1972.[45]

The laws establishing the 13 counties (shires), the historic counties of Wales,[46] assigned four for the five new counties created from the Marcher Lordships along the Welsh/English border, Brecknockshire, Denbighshire, Montgomeryshire and Radnorshire, to the legal system operated in Wales, administered by the Court of Great Sessions. Monmouthshire was assigned to the Oxford circuit of the English Assizes.[47] This began a legal separation which continued until 1972. For several centuries, acts of the Parliament of England (in which Wales was represented) often referred to "Wales and Monmouthshire", such as the Welsh Church Act 1914.[48]

Civil war and religious strife

[edit]Monmouthshire in the 1600s experienced to a high degree the political and religious convulsions arising from the English Reformation and culminating in the English Civil War. Following Henry VII's religious reforms, the county had a reputation for recusancy, with the strongly Catholic Marquesses of Worcester (later Dukes of Beaufort) at its apex, from their powerbase at Raglan Castle.[49] The outbreak of war saw the county predominantly Royalist in its sympathies; Henry Somerset, 1st Marquess of Worcester expended a fortune in support of Charles I and twice entertained him at Raglan. His generosity was unavailing; the castle fell after a siege in 1646; the marquess died in captivity and his son spent time in prison and in exile abroad.[50][51]

John Arnold was a firm enemy of Catholics and pursued a policy of harassment throughout the 1670s.[52] Monmouthshire’s only dukedom was created in 1663 for James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, but became forfeit following Scott’s execution after the failed Monmouth Rebellion in 1685.[53] In the 18th and much of the 19th centuries county politics was dominated by the Beauforts, and the Morgans, "an everlasting friendship between the house of Raglan and Tredegar".[54] By the late 19th century, three families held over a fifth of the land in Monmouthshire: the Beauforts, the Morgans, and the Hanburys of Pontypool.[55]

Industrialisation

[edit]

Industrialisation came early to Monmouthshire; the first brass in Britain was produced at a foundry at Tintern in 1568,[56] and the lower Wye Valley and the Forest of Dean became important centres for metalworking and mining. But the most dramatic impact was in the west of the county during the Industrial Revolution, in the South Wales Coalfield, where some of the largest pits in Wales were dug, and a major iron industry developed.[57] The societal transformation was accompanied by great inequality and unrest. Chartism was firmly embedded in Wales, and in 1840 the Chartist leaders John Frost, Zephaniah Williams and William Jones were tried for sedition and treason at the Shire Hall, Monmouth, after a failed insurrection at Newport. Their death sentences were subsequently commuted to transportation to Australia.[58]

Industrialisation also drove improvements in transportation; in the 18th century, the poor state of Monmouthshire's roads approached a national scandal. During a debate in parliament on the establishment of a turnpike trust for the county, the local landowner Valentine Morris asserted that the inhabitants of the county travelled "in ditches".[59] By the mid-century, commercial demands saw the first timetabled stagecoach between London and Monmouth arrive in Agincourt Square on 4 November 1763, the journey having taken four days.[60] By the end of the century, the need for access to exploit the South Wales coalfields saw the development of trams and canals.[61]

Society, art and science

[edit]Tourism became prominent in Monmouthshire at the end of the 18th century, when the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars precluded travel to Continental Europe.[62] The focus of activity was the Wye Tour, first popularised by the Rev. William Gilpin, in his Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales, etc. relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the summer of the year 1770. Although his efforts were sometimes satirised, Gilpin established what became the conventional route down the "mazy course" of the River Wye, with visitors embarking at Ross-on-Wye, and sailing past Symonds Yat, and Monmouth, before the highlight of the tour, Tintern Abbey.[63] Voyages concluded at Chepstow. The abbey at Tintern inspired artists and writers; J. M. W. Turner painted it;[64] William Wordsworth committed it to verse;[65] while Samuel Taylor Coleridge almost died there.[66] Another object of interest to artists undertaking the Wye Tour was the Monnow Bridge at Monmouth.[67] A late 18th-century watercolour by Michael Angelo Rooker is now in the Monmouth Museum.[68] The noted architectural watercolourist Samuel Prout painted the bridge in a study dated "before 1814", now held at the Yale Center for British Art in Connecticut.[69] In 1795, J. M. W. Turner sketched the bridge and gatehouse during one of his annual summer sketching tours.[70]

Alfred Russel Wallace, a naturalist whose independent work on natural selection saw Charles Darwin bring forward the publication of On the Origin of Species, was born at Llanbadoc, outside Usk, in 1823. He is commemorated in a statue raised in the town's Twyn Square in 2021.[71] Bertrand Russell, the philosopher and the only Nobel laureate from the county, was born at Cleddon Hall, outside Trellech in 1872.[72] Charles Rolls grew up at his family seat, The Hendre, just north of Monmouth and, in partnership with Henry Royce, co-founded Rolls-Royce Limited. He was also an aviation pioneer, and died in a plane crash in 1910.[73] He is commemorated by a statue in Agincourt Square in Monmouth.[74]

War

[edit]

The Royal Monmouthshire Royal Engineers was founded in 1539, making it the second oldest regiment in the British Army. Originally a county militia, it was amalgamated into the Royal Engineers in 1877. It is based at Monmouth Castle.[75]

Fitzroy Somerset, a younger son of the 5th Duke of Beaufort, enjoyed a long military career, serving on the staff of the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo,[76] and as commander-in-chief of the British forces during the Crimean War.[77] Created Baron Raglan in 1852, he died in 1855. His son was gifted Cefntilla Court, near Llandenny in his memory.[78] William Wilson Allen, who fought with the South Wales Borderers at the Battle of Rorke's Drift in 1879, is buried in Monmouth Cemetery, the only grave in the county of a holder of the Victoria Cross.[79][80]

The Monmouthshire Regiment was established in 1907. Men from the regiment fought in both the First and Second World Wars, until its disbandment in 1967.[81] HMS Monmouth was sunk at the Battle of Coronel in November 1914, with the loss of all 734 crew.[82]

Gwent 1974–1996

[edit]The Local Government Act 1972, which came into effect in April 1974, created the county of Gwent, confirmed it as part of Wales, and abolished the historic administrative county of Monmouthshire and its associated lieutenancy. It also subsumed Newport County Borough Council, creating a two-tier system of local government across the county. The entire county was administered by Gwent County Council, based at County Hall, Cwmbran, with five district councils below it: Blaenau Gwent, Islwyn, Monmouth, Newport and Torfaen.[83] The largest five towns in the new county were Newport, Cwmbran, Pontypool, Ebbw Vale and Abergavenny.[84]

Late 20th and 21st centuries

[edit]The Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 created the present local government structure in Wales of 22 unitary authority areas, the principal areas, and abolished the previous two-tier structure of counties and districts. It came into effect on 1 April 1996. It brought to an end the 22-year existence of Gwent, and re-created the county of Monmouthshire, although only with the eastern three-fifths of its historic area, and with a substantially reduced population. The western two-fifths of the county were included in other principal areas: Caerphilly County Borough, part of which came from Mid Glamorgan, including the towns of Newbridge, Blackwood, New Tredegar and Rhymney; Blaenau Gwent County Borough, including Abertillery, Brynmawr, Ebbw Vale and Tredegar; Torfaen County Borough, including Blaenavon, Abersychan, Pontypool, and Cwmbran; and the City of Newport, including Caerleon as it had since 1974. The new Monmouthshire, covering the less populated eastern 60% of the historic county, included the towns of Abergavenny, Caldicot, Chepstow, Monmouth and Usk.[85]

In his essay on local government in the fifth and final volume of the Gwent County History, Robert McCloy suggests that the governance of "no county in the United Kingdom in the twentieth century was so transformed as that of Monmouthshire".[2] The title of Gwent continues as a preserved county, one of eight such counties in Wales, which have mainly ceremonial functions such as the Lords Lieutenant and High Sheriffs. The current Lord Lieutenant of Gwent from 2016 is Brigadier Robert Aitken.[86] The current High Sheriff for 2023-2024 is Professor Simon J. Gibson.[87] It is also retained for a limited number of public service functions which operate across principal areas, for example Gwent Police.[88]

In the 1997 Welsh devolution referendum, which resulted in a narrow "Yes" vote, 50.30 per cent in favour v. 49.70 per cent against, for the establishment of a National Assembly for Wales, Monmouthshire recorded the highest "No" vote of any principal area, its population voting 67.9 percent against to 32.1 per cent in favour.[89]

Geography

[edit]Monmouthshire is broadly rectangular in shape, and borders the county of Powys to the north and the county boroughs of Newport, Torfaen and Blaenau Gwent to the west, with its southern border on the Severn Estuary giving the county its only coastline. To the east, it borders the English counties of Herefordshire and Gloucestershire.[90] The centre of the county is the plain of Gwent, formed from the basin of the River Usk, while the River Wye forms part of its eastern border, running through the Wye Valley, one of the five Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in Wales and the only one in the county.[91]

The north and west of the county is mountainous, particularly the western area adjoining the industrial South Wales Valleys and the Black Mountains which form part of the Brecon Beacons National Park. Two major river valleys dominate the lowlands: the scenic gorge of the Wye Valley along the border with Gloucestershire adjoining the Forest of Dean, and the valley of the River Usk between Abergavenny and Newport. Both rivers flow south to the Severn Estuary. The River Monnow is a tributary of the River Wye and forms part of the border with Herefordshire and England, passing through the town of Monmouth. The highest point of the county is Chwarel y Fan in the Black Mountains, with a height of 679 metres (2,228 ft). The Sugar Loaf (Welsh: Mynydd Pen-y-fâl or Y Fâl), located three kilometres (two miles) northwest of Abergavenny, offers far-reaching views; although its height is only 596 metres (1,955 ft), its isolation and distinctive peak shape make it a prominent landmark.[92]

Wentwood, now partly in Monmouthshire and partly in Newport, is the remnant of a once much larger forest, but remains the largest ancient woodland in Wales and the ninth largest in Britain.[93] Once a 3,000 hectares (7,400 acres) woodland, it formed the hunting ground for Chepstow Castle, and gave its name to a traditional north-south, division of the county between the cantrefi (hundreds) of Gwent Uwchcoed (above the wood) and Gwent Iscoed (below the wood).[94]

Geology

[edit]

Coastline and landscape

[edit]Monmouth's coastline forms its southern border, running the length of the Severn Estuary from Chepstow in the east to the shore south of Magor in the west. The distance, roughly 15 miles (24 km), can be walked via the Wales Coast Path.[95] The coastline includes the eastern part of the Caldicot and Wentloog Levels, also known as the Monmouthshire or Gwent Levels, an almost entirely man-made environment that has seen land reclamation since Roman times.[96]

Denny Island, a 0.24 hectares (0.6 acres) outcrop of rock in the Severn Estuary, the southern foreshore of which is the boundary between England and Wales, is Monmouthshire's only offshore island.[97]

Biodiversity

[edit]The battle to save Magor Marsh, the last remaining area of natural fenland on the Gwent Levels, led to the foundation of the Gwent Wildlife Trust.[98] The county contains a range of nature reserves and areas of special scientific interest, including Graig Wood 14.3-hectare (35-acre) SSSI, Pentwyn Farm Grasslands 7.6-hectare (19-acre) SSSI and Lady Park Wood National Nature Reserve (45.0-hectare (111-acre)).[99] The Wye Valley, the county's only National Landscape, has its largest population of deer and the UK's largest population of Lesser horseshoe bats.[100] The Wye itself was once one of the country's major centres of salmon fishing, but this has suffered very rapid decline in the 21st century due to river pollution.[101][i]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Monmouthshire | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.40 (52.52) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

15.16 (59.29) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.72 (35.10) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 127.3 (5.01) |

93.9 (3.70) |

74.8 (2.94) |

67.6 (2.66) |

73.9 (2.91) |

69.1 (2.72) |

66.2 (2.61) |

82.8 (3.26) |

75.8 (2.98) |

125.6 (4.94) |

120.9 (4.76) |

132.2 (5.20) |

1,110.7 (43.73) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 14.5 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 13.1 | 14.2 | 13.9 | 137.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 51.3 | 75.0 | 110.6 | 158.1 | 187.1 | 176.7 | 185.3 | 178.9 | 133.3 | 95.4 | 59.3 | 47.0 | 1,458.4 |

| Source: 1991–2020 averages for Usk climate station. Sources: Met Office[104] | |||||||||||||

Governance, politics and public services

[edit]Local governance

[edit]

The current unitary authority of Monmouthshire was created on 1 April 1996 as a successor to the district of Monmouth along with the Llanelly community from Blaenau Gwent, both of which were districts of Gwent. It is a principal area of Wales.[j] Monmouthshire is styled as a county, and includes: the former boroughs of Abergavenny and Monmouth; the former urban districts of Chepstow and Usk; the former rural districts of Abergavenny, Chepstow and Monmouth; the former rural district of Pontypool, except the community of Llanfrechfa Lower; and the parish of Llanelly from the former Crickhowell Rural District in Brecknockshire.[106]

The county is administered by Monmouthshire County Council, with its head office at Rhadyr, outside Usk, opened in 2013.[107][108][109] In the 2022 Monmouthshire County Council election, no party gained overall control, with the Welsh Labour party forming a minority administration, its 22 councillors allying with five Independents and one Green Party councillor. The council leader is Mary Ann Brocklesby.[110]

National representation

[edit]Monmouthshire elects one member to the UK parliament at Westminster, until 2024 representing the Monmouth constituency. Under the 2023 Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, a new constituency, Monmouthshire, came into effect at the 2024 general election, comprising 88.9% of the previous constituency.[111] The seat was won by the Labour Party candidate Catherine Fookes[112] who defeated the incumbent, David TC Davies, a Conservative Party politician who had held the previous seat since 2005 and who served as the Secretary of State for Wales in the prior government.[113] Monmouthshire directly elects two members to the Senedd, the Welsh parliament.

The Monmouth constituency covers most of the county and since May 2021 the directly elected member is Peter Fox,[114] a Conservative Party politician who previously served as the chair of Monmouthshire County Council.[115] The western edge of the county, bordering Newport and including the settlements of Magor, Undy, Rogiet and Caldicot, forms part of the Newport East constituency which has John Griffiths of Labour as its member.[116]

Monmouth is also one of eight constituencies in the South Wales East electoral region, which elects four additional members, under a partial proportional representation system.[117]

Public services

[edit]Fire and rescue services are provided by South Wales Fire and Rescue Service, which has fire stations in the county at Abergavenny, Caldicot, Chepstow, Monmouth and Usk.[118] Policing services are provided by Gwent Police, whose officers cover Monmouthshire, as well as Blaenau Gwent, Caerphilly, Newport and Torfaen.[119] Civilian oversight is provided by the Gwent Police and Crime Commissioner.[120] Monmouthshire's prisons are HM Prison Prescoed, a Category D open prison at Coed-y-paen and HM Prison Usk, a Category C prison, both in the west of the county.[121]

Demography

[edit]

Population

[edit]Monmouthshire's population was 93,000 at the 2021 census, increasing marginally from 91,300 at the 2011 census. 54,100 (58.2 per cent) of residents were born in Wales, while 32,300 (34.7 per cent) were born in England.[122] Just over 20 per cent of the county's population is over the age of 65. It remains one of the least densely-populated of Wales' principal areas.[123]

Language, ethnicity and identity

[edit]The 2021 census recorded that Welsh is spoken by 8.7 per cent of the population of the county, a decrease from 9.9 per cent in 2011. The number of non-Welsh speakers increased by 3,000 over the decade.[122] In 2021, 96.9 per cent of Monmouthshire residents identified as "white European", marginally lower than in 2011, compared with 98 per cent for the whole of Wales.[122] 41.9 per cent of the population identified as "Welsh", down from 44.0% in 2011. The percentage of residents in Monmouthshire that identified as "British only" increased from 23.5% to 27.0%.[122]

Religion

[edit]In the 2021 census 43.4 per cent of Monmouthshire residents reported having "No religion", an increase of nearly 15 per cent from the 28.5 per cent in the 2011 census. 48.7 per cent described themselves as "Christian" with the remainder reporting themselves as Buddhist (0.4 percent); Hindu (0.2 per cent); Jewish (0.1 per cent); Muslim (0.5 per cent); Sikh (0.1 per cent) or Other (0.6 per cent).[122]

Economy

[edit]Employment

[edit]

Monmouthshire is now primarily a service economy, with professional, scientific and technical businesses, financial services, IT and business administration, retail, hospitality and arts and entertainment businesses accounting for just over 50 per cent of the total number of enterprises in the county. Employers are generally small, with 91 per cent of businesses employing fewer than 10 people.[124] It is a relatively prosperous county in comparison with the average in Wales; 80.0 per cent of people of working age are in employment compared with the Welsh average of 72.8 per cent; just under 3,000 people were in receipt of the main unemployment benefit, a substantially lower number than in all of the adjoining principal areas; average annual earnings in 2020 were just over £41,000 compared to just over £32,000 in Wales as a whole. Total income tax payments from the county in 2013 were second only to the City of Cardiff, and the average individual payment exceeded that paid in the capital city.[125] Agriculture continues to be an important employer, accounting for 15.3 per cent of businesses, the second largest single sector after professional, scientific and technical enterprises. The Monmouthshire Show, an annual agricultural show, is one of the largest such events in Wales and has operated since 1790.[126] The third largest individual employment sector is construction.[124]

Transport

[edit]Road

[edit]

The only motorways are in the south of the county: the M4 which connects Wales with England via the Second Severn Crossing with its Welsh end near Sudbrook; and the M48, originally part of the M4,[127] which links Wales with England via the Severn Bridge at Chepstow.[128] In the east of the county, the A449 and the A40 link with the M50 near Goodrich, Herefordshire, connecting Monmouthshire and South Wales with the English Midlands.[129] The Department for Transport recorded traffic in Monmouthshire at 0.9 billion vehicle miles in 2022. This represented a lower level of road usage than in 2016.[k][130]

Rail

[edit]Monmouthshire is served by four railway stations: in the south are the Severn Tunnel Junction railway station at Rogiet on the South Wales Main Line, which connects South Wales to London; and Chepstow railway station and Caldicot railway station on the Gloucester–Newport line; and in the north, Abergavenny railway station on the Welsh Marches line.[131]

Bus services

[edit]The county's main centres of population are served by a bus network, connecting Abergavenny, Monmouth, Chepstow, Raglan and Usk, with stopping points at smaller settlements on route.[132] National coach services have stopping points at Monmouth and Chepstow.[133][134]

Waterways

[edit]

In its industrial heyday in the 18th and 19th centuries, the western part of the county was served by the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal which connected the South Wales Coalfield with the port at Newport. Today, the canal is a popular route for leisure cruising but most of its length lies within the principal areas of Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent and Newport.[135] The Monmouthshire villages of Gilwern, Govilon and Goetre, on the western extremity of the county, remain adjacent to the canal.[136]

Tourism

[edit]Tourism remains an important element of the county's economy. It generated just under £245 million in income in 2019, from 2.28 million visitors. The sector also provides employment for over 3,000 inhabitants of the county,[124] approximately 10 per cent of the total working population.[123]

Education and health

[edit]Higher, further, secondary, primary and special education

[edit]

The county has neither a university nor any satellite campus.[l][138] The former University of Wales, Newport operated a campus at Caerleon which closed in 2016, following the 2013 merger which created the University of South Wales.[139] Higher education courses in the county are provided through the campus of Coleg Gwent at Rhadyr, near Usk.[140]

There are four maintained secondary schools in the county,[141] Caldicot School, serving the south of the county; Monmouth Comprehensive School serving the east; Chepstow School, serving the town of Chepstow and the surrounding villages; and King Henry VIII 3-19 School in Abergavenny, serving the town and the north of the county. All have sixth-forms.[142] There was one special school, Mounton House School, based at Mounton House near Chepstow, but that was closed in 2020, and there is currently no specific special school provision.[143] There are 30 primary schools of which two are Welsh language medium. There are no full Welsh language medium secondary schools, although all offer the option of studying Welsh.[141] The only independent secondary provision in the county are the two schools at Monmouth, Monmouth School for Boys and Monmouth School for Girls, both operated by the Haberdashers' Company.[144]

Health services

[edit]The Aneurin Bevan University Health Board is the Local health board for Gwent within NHS Wales and has responsibility for health care within the county.[145] The largest hospital in the county is the Nevill Hall Hospital at Abergavenny. Its range of services has reduced following the opening of the specialist critical care centre at the Grange University Hospital in Torfaen in 2020. The Grange is also the designated trauma centre for Gwent, which covers Monmouthshire.[146] The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 established Public Services Boards throughout Wales to oversee health and well-being, and following reorganisation in 2021 a Gwent public services board was created to have oversight for Monmouthshire, Blaenau Gwent, Caerphilly, Newport and Torfaen.[147]

Culture

[edit]

Flag

[edit]The flag of Monmouthshire was officially adopted in 2011.[148] It features three gold fleur-de-lis on a black/blue background.[149]

Built and landscape heritage

[edit]Monmouthshire has 2,428 listed buildings,[150] including 54 at Grade I,[151] the highest grade, and 246 at Grade II*, the next highest grade.[152] These include churches, a priory and an abbey and a number of castles. The journalist Simon Jenkins notes the county's "fine collection" of these,[153] mostly dating from the Norman invasion of Wales, and describes Chepstow as "the glory of medieval south Wales".[154] The castle at Raglan is later, dating from the mid-fifteenth century.[155] The fortified bridge over the River Monnow at Monmouth is the only remaining fortified river bridge in the country with its gate tower standing on the bridge, and has been described as "arguably the finest surviving medieval bridge in Britain".[156] Monmouthshire has a more "modest"[153] range of churches, although that at Bettws Newydd has "perhaps the most complete rood arrangement remaining in any church in England and Wales".[157] The county's Grade I listed abbey, at Tintern, became a focal point of the Wye Tour[158] in the late-eighteenth century.[159]

Sport and leisure

[edit]

Monmouthshire has rugby union clubs at Abergavenny and Monmouth,[160][161] and an invitational county team, Monmouthshire County RFC. It has football clubs at Abergavenny,[162] Caldicot,[163] Chepstow[164] and Monmouth.[165] The football clubs play in the Ardal Leagues[166] and the Gwent County League.[167] Monmouthshire County Cricket Club was established in the 19th century and achieved a notable victory in 1858 when a Monmouthshire XXII beat an All-England XI at a match on Newport Marshes. The club suffered financial difficulties in the 1930s and merged with Glamorgan County Cricket Club in 1934.[168] Monmouthshire has a rowing tradition on the River Wye, with the Monmouth Rowing Club, founded in 1928,[169] and all three of the town's secondary schools having their own rowing clubs.[170][171][172]

Chepstow Racecourse hosts the Coral Welsh Grand National, the richest thoroughbred horse racing event in Wales.[173] The Rolls of Monmouth Golf Club at Rockfield is ranked in the 50 top courses in Wales,[174] while the St Pierre course in the south of the county hosted the Epson Grand Prix of Europe and the British Masters in the late 20th century.[175]

A number of long-distance footpaths pass through the county, including the Marches Way, the Three Castles Walk, Offa's Dyke Path, the Usk Valley Walk, the Monnow Valley Walk and the Wye Valley Walk.[176] Chepstow is a terminus for two long-distance cycle routes which form part of the National Cycle Network: National Cycle Route 8 which runs from either Chepstow of Cardiff in the south to Holyhead in the north, and the Celtic Trail cycle route which runs east to west, from Chepstow to Fishguard.[177]

Cuisine

[edit]

The cuisine of Monmouthshire traditionally focused on its local produce, including lamb and mutton from sheep farming in the hillier north of the county,[178] poultry and game.[179] Lady Llanover (bardic name Gwenynen Gwent — "the bee of Gwent"), was an early champion of Welsh culture and cuisine; her First Principles of Good Cookery, published in 1867, was one of the first Welsh cookery books.[180] The contemporary writer, Gilli Davies, in her study of Welsh food, Tastes of Wales, writes of the "rare and appealing quality to the food in Monmouthshire".[181] The county has a small viniculture industry, with vineyards at Ancre Hill Estates, north of Monmouth; White Castle vineyard near Abergavenny,[182] and the Tintern Parva vineyard in the Wye Valley.[183][184] There are two Michelin starred restaurants in Monmouthshire, The Walnut Tree at Llanddewi Skirrid,[185] in the north of the county and The Whitebrook at Whitebrook in the east.[186][187] Abergavenny Food Festival is held annually each September. Established in 1991, it has been described as one of Britain's best food and produce events.[188][189][190]

Media, the arts and local history

[edit]

Monmouthshire has three local newspapers, the Abergavenny Chronicle, the Forest of Dean and Wye Valley Review and the Monmouthshire Beacon. All are published by Tindle, a regional media group.[191] Digital reporting is provided by the Monmouthshire Free Press Series.[192] Sunshine Radio (Herefordshire and Monmouthshire) is the only local radio station, although it is based in Hereford.[193] Rockfield Studios is a major residential recording studio which has seen bands and artists such as Coldplay, Oasis and the Manic Street Preachers record material. Queen recorded most of "Bohemian Rhapsody" at Rockfield in 1975.[194]

There are two theatres in Monmouthshire, the Borough Theatre in Abergavenny,[195] and the Savoy Theatre, Monmouth. Operated by a charitable trust, the Savoy claims to be the oldest theatre in Wales.[196] Museums of local life are located at Abergavenny,[197] Chepstow,[198] Usk[199] and Monmouth. During the closure of the Monmouth museum in 2020-2021 in the COVID-19 pandemic, the council announced that the museum would not re-open and that its collections, including an important assemblage of memorabilia related to Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson donated to the town by Georgiana, Lady Llangattock,[200] would be relocated to the Shire Hall. The museum's Market Hall site would be redeveloped for commercial use. The council intends to complete the transfer by 2027.[201] The Monmouth Regimental Museum, located at Great Castle House in Monmouth, contains material related to the Royal Monmouthshire Royal Engineers, the second-oldest regiment in the British Army.[202]

Historiography

[edit]

The development of tourism in the late 18th century saw the writing of a number of histories of the area, which frequently combined the features of a guidebook with a more formal historical approach. Among the first was William Gilpin's Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales, etc. relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the summer of the year 1770, published in 1782.[205] Among the most notable was William Coxe's two-volume An Historical Tour in Monmouthshire, published in 1801. Coxe's preface explains the Tour's genesis: "The present work owes its origin to an accidental excursion in Monmouthshire, in company with my friend Sir Richard Hoare, during the autumn of 1798."[206] A detailed county history was undertaken by Sir Joseph Bradney, in his A History of Monmouthshire from the Coming of the Normans into Wales down to the Present Time, published over a period of 30 years in the early 20th century.[207]

Studies of the architecture of the county include John Newman's, Gwent/Monmouthshire volume of the Pevsner Buildings of Wales series; and, most exhaustively, Sir Cyril Fox and Lord Raglan's, three-volume study, Monmouthshire Houses.[208] This was described by the architectural historian Peter Smith, author of the magisterial Houses of the Welsh Countryside, as "one of the most remarkable studies of vernacular architecture yet made in the British Isles,[209] a landmark, in its own field, as significant as Darwin's Origin of Species".[210]

The 20th century saw the publication of two lesser histories: Hugo Tyerman and Sydney Warner's Monmouthshire volume of Arthur Mee's The King's England series in 1951;[158] and Arthur Clark's two-volume The Story of Monmouthshire, published in 1979–1980.[211][212] The history of the county was covered in more anecdotal form by the Monmouthshire writer and artist Fred Hando, who chronicled the highways and byways of the county in some 800 newspaper articles written from the 1920s until his death in 1970 and published in the South Wales Argus, focusing on "the little places of a shy county".[204] The 21st century saw the publication of the county's most important history, the five-volume Gwent County History. The series, modelled on the Victoria County History, had Ralph A. Griffiths as editor-in-chief, and was published by the University of Wales Press between 2004 and 2013. It covered the history of the county from prehistoric times to the 21st century.[213][214]

See also

[edit]- Monmouthshire (historic)

- Gwent (county)

- Lord Lieutenant of Monmouthshire

- Lord Lieutenant of Gwent

- Sheriff of Monmouthshire

- High Sheriff of Gwent

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Meoslithic footprints, dated to about 8,000 years ago, have been uncovered on the foreshore of the Severn Estuary at Goldcliff, formerly in Monmouthshire but now in Newport.[4]

- ^ Much the most important Roman site in the area is Isca Augusta, at Caerleon, founded as the headquarters of the Augustan Second Legion in around AD 75. The site was historically in Monmouthshire, but is now part of Newport.[15]

- ^ Modern scholarship suggests a greater role for migration, co-existence, and inter-marriage between the incoming Anglos-Saxons and the native inhabitants, and a lesser role for invasion and combat, as recounted by chroniclers from Gildas onwards.[19]

- ^ Raymond Howell, in his county history published in 1988, notes the significance of the retention by the Kingdom of Gwent of both banks of the lower River Wye at the time of Offa’s construction work, indicating their ability to treat almost as equals with the most powerful of the Saxon kingdoms.[22]

- ^ Howell writes, "as literature, Geoffrey's work was a classic, as history it was virtually useless. Nevertheless, because of wide-spread influence, the myths of Geoffrey became institutionalized as history".[30] Neil Wright is equally clear, "the Historia does not bear scrutiny as an authentic history and no scholar today would regard it as such".[29]

- ^ Henry’s statue is generally considered to be of poor quality; John Newman considered it "incongruous",[34] Jo Darke called it "decidedly-bad",[35] while the local historian Keith Kissack attacked it in two separate books, describing it as, "rather deplorable",[36] and "pathetic...like a hypochondriac inspecting his thermometer".[37]

- ^ The most famous of Henry V's Welsh supporters was Dafydd Gam. Shakespeare's character, Fluellen, who appears in Henry V and has been suggested as being modelled on Gam, reminds the king; "If your Majesty is remembered of it, the Welshmen did good service in a garden where leeks did grow, wearing leeks in their Monmouth caps, which your Majesty knows, to this hour is an honourable badge of the service, and I do believe, your Majesty takes no scorn to wear the leek upon Saint Tavy's day".[40]

- ^ Coflein's entry for the battle site notes the traditional ascription to the hill but records that archaeological investigations have not uncovered evidence to support the claim.[42]

- ^ The pollution of the River Wye is primarily attributed to the large-scale battery farming of poultry, with an estimated 23 million birds being bred in the river catchment area in 2023.[102][103]

- ^ The use of the name "Monmouthshire" rather than "Monmouth" for the area aroused some controversy; it was supported by the member of parliament (MP) for Monmouth, Roger Evans, but opposed by Paul Murphy, MP for Torfaen (inside the historic county of Monmouthshire but being reconstituted as a separate unitary authority).[105]

- ^ The Department for Transport notes that the decline in road traffic usage between 2016 and 2022 was almost entirely due to the dramatic fall in usage due to movement restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom.[130]

- ^ The closest university to Monmouthshire is the campus of the University of South Wales at Newport.[137]

References

[edit]- ^ "How life has changed in Monmouthshire: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. 19 January 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ a b McCloy 2013, p. 126.

- ^ "Historic Landscape Characterisation - The Gwent Levels". Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "Severn Estuary Levels Research Committee". Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "Items found in Monmouth shed light on Mesolithic man". BBC News. 8 November 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 17.

- ^ Cadw. "Bulwarks Prehistoric Enclosure (MM093)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Cadw. "Llanmelin Wood Hillfort (MM024)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ "Llanmelin Wood Hillfort (301559)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ a b Howell 1988, p. 25.

- ^ "BBC Wales - History - Themes - Wales and the Romans". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Caerwent Roman City - Venta Silurum (93753)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 29.

- ^ "Monmouth Roman fort (409995)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ Cadw. "Caerleon Legionary Fortress (MM230)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 30.

- ^ "The Celtic kingdoms of Britain". The History Files. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 40.

- ^ Härke 2011, pp. 1–28.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 41.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 45.

- ^ Howell 1988, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 47.

- ^ Davies 1992, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Wood, Hugh. "Marcher Lordships".

- ^ Nelson 1966, p. ?.

- ^ Cadw. "Chepstow Castle (MM003)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ Cadw. "Llangibby Castle (Castell Tregrug) (MM109)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ a b Wright 1984, xxviii.

- ^ Howell 1988, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 58.

- ^ Ormrod 2005.

- ^ Knight 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Newman 2000, p. 401.

- ^ Darke 1991, p. 141.

- ^ Kissack 2003, p. 33.

- ^ Kissack 1978, p. 94.

- ^ Allmand 2010.

- ^ Howell 1988, p. 62.

- ^ Cottis, David; Mordsley, Jessica. "Shakespeare and Wales". British Council. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "The Story of Usk - Glyndwr's Revolt". Usk Town Council. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Craig-y-dorth, site of battle, near Monmouth (402327)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Thomas-Symonds 2004, p. 14.

- ^ "More about Raglan Castle". Cadw. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972". The National Archives (United Kingdom). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Union, Act of (Wales)". Oxford Reference.

- ^ "Legal Records Relating to Wales". National Archives. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Welsh Church Act 1914". The National Archives (United Kingdom). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Jenkins 1986, p. 562.

- ^ Tribe 2002, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Kenyon 2003, p. 19.

- ^ "John Arnold (c.1635-1702) of Llanvihangel Crucorney". History of parliament online. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "No. 2051". The London Gazette. 13 July 1685. p. 2.

- ^ Jenkins 1986, p. 568.

- ^ Jenkins 1986, p. 574.

- ^ "Industrial Revolution". Visit Dean Wye.

- ^ "Iron and coal" (PDF). Archives Wales. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Chartist Trial 16th January 1840". NewportPast. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Weeks 2009, p. 243.

- ^ Weeks 2009, p. 245.

- ^ Weeks 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Andrews 1989, p. 86.

- ^ Gilpin 1782, p. 17.

- ^ "'Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking towards the East Window', Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1794". Tate.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (13 May 2024). "Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798 by William Wordsworth". Poetry Foundation.

- ^ Cottle 1837, p. 48.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 106.

- ^ "Monnow Bridge and Gate, Monmouth by Michael Angelo Rooker". Art Fund. 28 January 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Yale Center for British Art, Lec Maj. "The Monnow Bridge, Monmouthshire". Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Joseph Mallord William Turner, 'The Monnow Bridge, Monmouth' 1795 (J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours)". Tate. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Hartland, Nick (6 November 2021). "Comedian to unveil bust of famous son Wallace". Abergavenny Chronicle. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Henry, Graham (12 July 2012). "Nobel winner Bertrand Russell's Welsh birthplace on sale for £2m". Wales Online. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Charles Rolls – The Life of the Motoring and Aviation Pioneer". Rolls-Royce Motors. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Cadw. "Statue of C S Rolls (Grade II*) (2229)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "The Origins of the Regiment". Regimental Museum. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "No. 17028". The London Gazette. 22 June 1815. p. 1216.

- ^ Bradney 1992, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Newman 2000, pp. 272–273.

- ^ "Victoria Cross burials in Monemouthshire". Victoria Cross Society. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "War hero remembered in special service at Monmouth Cemetery". Monmouthshire Beacon. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "World Wars". Castle and Regimental Museum, Monmouth. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Battle of Coronel". World War 1 at Sea - Naval Battles in outline with Casualties. naval-history.net. 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "The Counties and Districts - Gwent". Western Mail ("The New Wales" supplement). Wales. 22 March 1974. p. 8.

- ^ "Monmouthshire". County-Wise. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "Local Government (Wales) Act 1994". The National Archives (United Kingdom). Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Home - Lord Lieutenant of Gwent". 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Meet the Team". Office of the High Sheriff of Gwent. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "About us". Gwent Police. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Welsh devolution referendum - Monmouthshire results". BBC Wales. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire, Wales, Map, History, & Facts". www.britannica.com. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty - Management Plan 2004-2009" (PDF). Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "The Sugar Loaf walk, Abergavenny". Brecon Beacons National Park. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "70 ancient woodlands" (PDF). The Queen's Green Canopy. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Gwent". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Wales Coast Path". Visit Monmouthshire.

- ^ "Glamorgan Gwent Archaeology is part of Heneb: The Trust for Welsh Archaeology". Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Autumn/Winter Wild About Gwent 2022 by Gwent Wildlife Trust - Issuu". issuu.com. 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Magor Marsh". Gwent Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature Reserves". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Wildlife - Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty". Wye Valley AONB. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Fish - Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty". Wye Valley AONB. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "River Wye pollution leads chicken firm Avara to be sued". BBC Wales. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Laville, Sandra (7 February 2024). "Environment Agency failed to protect River Wye from chicken waste, court hears". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Station: Usk, Monmouthshire". Meteorological (Met) Office. 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Hansard, House of Commons, March 15, 1994, Column 782". Parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, Schedule 1". Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire County Council press release, "This council is coming home", 12 January 2010". Monmouthshire.gov.uk. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Monmouthshire move into new HQ". Willmott Dixon. 21 May 2013.

- ^ Gabriel, Clare (18 April 2013). "'Agile working' office savings aim". BBC News. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Your councillors". Monmouthshire County Council. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Boundary Review 2023 - which seats will change". House of Commons Library. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Owen, Twm (5 July 2024). "General election 2024: Labour win in Monmouthshire". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "The Rt Hon David TC Davies MP". UK Government. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Ruth Mosalski; Sian Burkitt (7 May 2021). "Monmouth Conservative candidate for Senedd Election Peter Fox". Wales Online. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Emotional Peter Fox closes "huge chapter" in his life as he stands down as council leader". Free Press Series. 14 May 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Your MPs". democracy.monmouthshire.gov.uk. 27 July 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Glossary of terms - Region". Senedd Cymru. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Home". South Wales Fire and Rescue Service. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire". Gwent Police. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Your Police and Crime Commissioner". Office of the Gwent Police and Crime Commissioner. 3 August 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Usk and Prescoed - continuing high standards at two Welsh prisons". His Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "How life has changed in Monmouthshire: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Facts about Monmouthshire". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Baseline Characteristics of Monmouthshire June 2021" (PDF). Monmouthshire County Council. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Miller, Claire (21 May 2013). "The Welsh wealth map: Biggest income tax payers live in Monmouthshire, Cardiff and the Vale". Wales Online. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire Show". The Voice Magazines. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "M4 Motorway, M48 Motorway, South Wales (417517)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Our roads | Traffic Wales". traffic.wales.

- ^ "M50, A40 and A449 | Roads.org.uk". www.roads.org.uk. 28 November 1960.

- ^ a b "Road traffic statistics - Local authority: Monmouthshire". roadtraffic.dft.gov.uk.

- ^ "Transport and travel - Rail". Monmouthshire County Council. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Bus Timetables". Monmouthshire County Council. 6 November 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Transport and travel". Monmouthshire County Council. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Coach Routes Map & Stops Finder". National Express Coaches. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal". Canal and River Trust. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire-Brecon Canal". Brecon Beacons National Park. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Welcome to Newport Campus". University of South Wales. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Universities in Monmouthshire, Wales". UK Universities.net. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "University of Wales, Newport to be dissolved in April 2013". South Wales Argus. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Usk campus, Coleg Gwent". Coleg Gwent. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Secondary schools in Monmouthshire, Wales". Level Playing Field. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Secondary schools in Monmouthshire, Wales". Monmouthshire County Council. 22 January 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Mounton House special school closure backed by council". BBC Wales. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Independent schools in Monmouth". Independent Schools Council. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "The Health Board". Aneurin Bevan University Health Board. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Nevill Hall Hospital". Aneurin Bevan University Health Board. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Gwent Public Services Board". Gwent Public Services Board. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire Flag Registered". Association of British Counties. 30 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012.

- ^ "The Monmouthshire Association — the official county flag". Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Listed Buildings in Monmouthshire". British Listed Buildings Online. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Grade I Listed Buildings in Monmouthshire". British Listed Buildings Online. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Grade II* Listed Buildings in Monmouthshire". British Listed Buildings Online. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Jenkins 2008, p. 169.

- ^ Jenkins 2008, p. 174.

- ^ Hayman 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Newman 2000, p. 120.

- ^ a b Tyerman & Warner 1951, p. 3.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, pp. 65–74.

- ^ "Abergavenny Rugby Football Club". Abergavenny RFC. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Monmouth Rugby Football Club". Monmouth RFC. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Abergavenny Town Football Club". Soccerway.com. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Caldicot Town Football Club". Caldicot Town FC. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Chepstow Town Football Club". Ardal Leagues. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Monmouth Town Football Club". Monmouth Town FC. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Ardal Leagues South-East". Cymru Football. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Gwent County League". pitchero.com. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire". CC4 Museum of Welsh Cricket. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Welcome page". Monmouth Rowing Club. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "About MCSBC". Monmouth Comprehensive School. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Rowing". Monmouth School for Girls. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Rowing". Monmouth School for Boys. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Coral Welsh Grand National". www.chepstow-racecourse.co.uk. Chepstow Racecourse. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Top Golf Course and Wedding Venue in Wales". The Rolls of Monmouth Golf Club. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "St Pierre Golf Club (Old Course)". Golf Southwest. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Walking routes and trails". Monmouthshire County Council. 6 February 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Sport in Monmouthshire". Kingfisher Guides. 20 July 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire farmer wins industry award". South Wales Argus. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Producers". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Hall, Augusta. "The first principles of good cookery illustrated : and recipes communicated by the Welsh hermit of the cell of St. Gover, with various remarks on many things past and present". Worldcat. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Davies 1990, p. 70.

- ^ "Welsh vineyards 'could increase to 50 by 2035'". BBC Wales. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Tintern vineyard wins 'best white wine in Wales' award". South Wales Argus. 18 November 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Wilson, Matthew (12 May 2016). "How Welsh wine is wooing connoisseurs". Financial Times. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Walnut Tree – Llanddewi Skirrid". Michelin. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Michelin-starred Crown at Whitebrook in surprise name change under new chef Chris Harrod". Wales Online. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Monmouthshire Michelin Restaurants". Michelin Guide. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "The UK's best food festivals: What to book in 2023".

- ^ "The UK's best food and drink festivals in 2024". The Week. 11 May 2021.

- ^ Paris, Natalie (19 August 2023). "The ultimate guide to Britain's best autumn food festivals – to book now". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Portfolio - Tindle News". tindlenews.co.uk. Tindle News. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Free Press - in Chepstow, Pontypool, Caldicot & Wales". www.freepressseries.co.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Analogue Radio Stations". Ofcom. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Rockfield - The Legendary Welsh Recording Studios". Rockfield Studios. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Borough Theatre to finally reopen its doors this week". Abergavenny Chronicle. 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Monmouth theatre gets £6k boost". Monmouthshire Free Press. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Abergavenny Museum". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Chepstow Museum". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Usk Rural Life Museum". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Shire Hall Museum". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Shire Hall Museum". Monlife. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Monmouth Castle & Regimental Museum". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Hando 1958, pp. 115–117.

- ^ a b Hando 1944, p. 15.

- ^ Gilpin 1782.

- ^ Coxe 1995a, Preface.

- ^ Bradney 1991, preface.

- ^ Fox & Raglan 1994, preface.

- ^ Smith 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Newman 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Clark 1979, Introduction.

- ^ Clark 1980, Introduction.

- ^ Green 2004.

- ^ Griffiths, Williams & Croll 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Allmand, Christopher (23 September 2010). "Henry V (1386–1422)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12952. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Andrews, Malcolm (1989). The Search for the Picturesque: landscape aesthetics and tourism in Britain, 1760-1800. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804-71402-0.

- Aslet, Clive (2005). Landmarks of Britain. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-73510-7.

editions:O60YB-B7LYMC.

- Bradney, Joseph (1991). A History of Monmouthshire: The Hundred of Skenfrith, Volume 1 Part 1. London: Academy Books. ISBN 978-1-873-36109-2.

- — (1992). A History of Monmouthshire: The Hundred of Raglan, Volume 2 Part 1. London: Academy Books. ISBN 978-1-873-36115-3.

- Clark, Arthur (1953). Raglan Castle and the Civil War in Monmouthshire. Newport, Wales: Newport & Monmouthshire Branch of the Historical Association and Chepstow Society. OCLC 249172228.

- — (1980). The Story of Monmouthshire, Volume 1, From the earliest times to the Civil War. Monmouth: Monnow Press. ISBN 978-0-95066-1810. OCLC 866777550.

- — (1979). The Story of Monmouthshire, Volume 2, From the Civil War to Present Times. Monmouth: Monnow Press. ISBN 978-0-95066-1803. OCLC 503676874.

- Cottle, Joseph (1837). Early recollections: chiefly relating to the late Samuel Taylor Coleridge. London: Longman. OCLC 911202568.

- Coxe, William (1995) [1801]. An Historical Tour of Monmouthshire: Volume 1. Cardiff: Merton Priory Press. ISBN 978-1-898-93709-8.

- — (1995) [1801]. An Historical Tour of Monmouthshire: Volume 2. Cardiff: Merton Priory Press. ISBN 978-1-898-93708-1.

- Darke, Jo (1991). The Monument Guide to England and Wales: A National Portrait in Bronze and Stone. London: MacDonald and Co. ISBN 978-0-356-17609-3.

- Davies, Gilli (1990). Tastes of Wales. London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-36043-8.

- Davies, R. R. (1992) [1987]. The Age of Conquest: Wales, 1063–1415. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-19-820198-2.

- Evans, Cyril James Oswald (1953). Monmouthshire: Its History and Topography. Cardiff: William Lewis Printers. OCLC 2415203.

- Fox, Cyril; Raglan, Lord (1994). Medieval Houses. Monmouthshire Houses. Vol. 1. Cardiff: Merton Priory Press Ltd & The National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0-72000-3963. OCLC 916186124.

- Gilpin, William (1782). Observations on the river Wye, and several parts of South Wales, &c. relative chiefly to picturesque beauty, made in the summer of the year 1770. London.

- Green, Miranda (2004). Prehistory and Early History. Gwent County History. Vol. 1. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1826-3.

- Griffiths, Ralph A.; Williams, Chris; Croll, Andy (2013). Chris Williams (ed.). The Twentieth century. Gwent County History. Vol. 5. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708326480.

- Hando, Fred (1944). The Pleasant Land of Gwent. Newport: R. H. Johns Ltd. OCLC 2534151.

- — (1951). Journeys in Gwent. Newport: R. H. Johns Ltd. OCLC 30202753.

- — (1954). Monmouthshire Sketch Book. Newport: R. H. Johns Ltd. OCLC 30166792.

- — (1958). Out and About in Monmouthshire. Newport: R. H. Johns Ltd. OCLC 30235598.

- Härke, Heinrich (November 2011). "Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis". Medieval Archaeology. 55 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1179/174581711X13103897378311. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- Hayman, Richard (2016). Wye. Woonton Almeley: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-91083-9096.

- Howell, Raymond (1988). A History of Gwent. Llandysul: Gomer Press. ISBN 978-0-863-83338-0.

- Jenkins, Philip (1986). "Party Conflict and Political Stability in Monmouthshire, 1690-1740". The Historical Journal. 29 (3): 557–575.

- Jenkins, Simon (2008). Wales: Churches, Houses, Castles. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-713-99893-1.

- Kenyon, John (2003). Raglan Castle. Cardiff, Wales: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-857-60169-5.

- — (2010). The Medieval Castles of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-708-32180-5.

- Kissack, Keith (2003). Monmouth and its Buildings. Logaston Press. ISBN 1-904396-01-1.

- — (1978). The River Wye. Lavenham: Terence Dalton. ISBN 9780900963797.

- Knight, Jeremy K. (2009) [1991]. The Three Castles: Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, White Castle (revised ed.). Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-857-60266-1.

- McCloy, Robert (2013). "Local government". In Williams, Chris; Croll, Andy; Griffiths, Ralph A. (eds.). The Twentieth Century. Gwent County History. Vol. 5. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-708-32648-0.

- Mitchell, Julian (2010). The Wye Tour And Its Artists. Woonton Almeley: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-906-66332-2.

- Nelson, Lynn H. (1966). The Normans in South Wales - 1070–1171. Austin, Texas and London: University of Texas Press. Archived from the original on 10 April 2005. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Newman, John (2000). Gwent/Monmouthshire. The Buildings of Wales. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-300-09630-9.

- Ormrod, W. M. (2005). "Henry of Lancaster, First Duke of Lancaster (c.1310–1361)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12960. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Smith, Peter (1975). Houses of the Welsh Countryside. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-117-00475-7.

- Thomas-Symonds, Nick (Autumn 2004). "The Battle of Grosmont, 1405: A Re-interpretation". Journal of the Gwent Local History Council. 97: 3–23. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Tribe, Anna (2002). Raglan Castle and the Civil War. Caerleon: Monmouthshire Antiquarian Association.

- Tyerman, Hugo; Warner, Sydney (1951). Arthur Mee (ed.). Monmouthshire. The King's England. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 764861.

- Weeks, Robert (2009). "Transport and Communications". In Gray, Madeleine; Morgan, Prys (eds.). The Making of Monmouthshire, 1536-1780. Gwent County History. Vol. 3. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-708-32198-0.

- Wright, Neil Geoffrey (1984). The Historia Regum Britannie of Geoffrey of Monmouth. 1, A Single-Manuscript Edition from Bern, Burgerbibliothek, MS. 568. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-859-91211-2.