Isaac Perrins

Isaac Perrins was an English bareknuckle prizefighter and 18th-century engineer. A man reputed to possess prodigious strength but a mild manner, he fought and lost one of the most notorious boxing matches of the era, a physically mismatched contest against the English Champion Tom Johnson. Such was the mismatch that Perrins was described as Hercules fighting a boy.

During the period when he was prizefighting Perrins worked for Boulton and Watt, manufacturers of steam engines, based at their Soho Foundry, Birmingham, but also travelled around the country and at times acted as an informant on people who were thought to have breached his employer's patents. In the later years of his life he also ran a public house in Manchester and undertook engineering work on his own account. He was appointed to lead the Manchester fire brigade in 1799, and died a little over 12 months later in the performance of his duties.

Early life

[edit]There is little information regarding Issac Perrins' early life, but he was probably born around 1751. His father, also called Isaac, worked for Boulton and Watt erecting stationary steam engines in the West Midlands until his death in 1780. In that year Isaac junior was offered work in Cornwall by the business but turned it down. He subsequently accepted a Birmingham-based job with the firm in 1782.[1]

Prizefighting

[edit]Bareknuckle fighting was "particularly popular" in Birmingham during Perrins' lifetime.[2] From a legal standpoint such fights ran the risk of being classified as disorderly assemblies but in practice the authorities were concerned mainly about the number of criminals congregating there. The patronage of the aristocracy – including royal princes and dukes – and other wealthy people ensured that any legal scrutiny was generally benign, in particular because fights could take place on private estates.[3][4] There was increased support for the sport from around 1786 because of the interest shown in it by the Prince of Wales (later King George IV) and his brothers, the future King William IV and Duke of Kent.[5]

Prizefighting in early 18th-century England took many forms rather than just pugilism, which was referred to by noted swordsman and then boxing champion James Figg as "the noble science of defence". By the middle of the century the term was generally used to denote boxing fights only.[6] The appeal of prizefighting at that time has been compared to that of duelling, with historian Adrian Harvey saying that

Patriotic writers often extolled the manly sports of the British, claiming that they reflected a courageous, robust, individualism in which the nation could take pride. Pugilism was regarded as humane and fair and its practice was presented in chivalrous terms. It was also a symbol of national courage, embodying the worth which Englishmen placed upon their own individual honour. The French, it was argued, did not like pugilism because they were not a free people and relied on the authorities to resolve their disputes. By contrast, the British dealt with their own problems in a straightforward manner, according to established rules of fair play.[4]

Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham reported that although pugilism was long practised in the area the first local records it could find were of a prizefight on 7 October 1782 at Coleshill between Isaac Perrins, "the knock-kneed hammerman from Soho", and a professional called Jemmy Sargent.[7] The fighters received 100 guineas each. Perrins won in around six minutes, after knocking Sargent down thirteen times. Perrins' friends apparently won £1,500 with their betting.[8] This record is an exception to the rule: the records of fights are not detailed for this period and particularly so in the case of those which did not involve men from London. Unless a death or some other remarkable incident occurred, the information is scarce.[9]

London was the premier centre for boxing because the aristocratic supporters of the sport dispersed to their country estates during the summer months but tended to congregate in the city for the winter period.[3] Birmingham was often portrayed as second only to London for the sport[2] and in 1789 there were a series of challenges issued by fighters from the Birmingham area to opponents based around London. The challenges were intended to demonstrate the level of organisation and confidence among the Birmingham boxers and their supporters.[10] Three of these challenges were accepted, including that from Perrins to Tom Johnson. Perrins had already issued a general challenge, offering to fight any man in England for a prize of 500 guineas, having beaten all challengers in the counties around Birmingham.[11]

The Perrins – Johnson fight took place at Banbury on 22 October 1789 and was billed as a battle between Birmingham and London as well as for the English Championship. The venue had been intended to be Newmarket during a race meeting but permission could not be obtained.[11] The two men were around the same age but physically very different.[12] Perrins stood 6' 2" (1.88 m) tall and weighed 238 pounds (108 kg), while Johnson was 5' 10" (1.78 m)[12] and weighed 196 pounds (89 kg). It was claimed that Perrins had lifted 896 pounds (406 kg) of iron with ease,[13] and he was "universally allowed to possess much skill and excellent bottom".[11] That is, it was acknowledged that he was skilful and courageous. The physical mismatch was later described as a fight between Hercules, in the form of Perrins, and a boy.[14]

The first five minutes of competition saw neither man strike a blow and then when Perrins tried to make contact Johnson dodged and felled Perrins in return. Although Perrins recovered to hold the upper hand in the first few rounds, Johnson then began to dance around the ring, forcing Perrins to follow to make a fight of it. This "shifting" confused Perrins because the custom at the time was for the fighters to stand still and hit each other, but the rules for this particular fight did not prevent it. Nor did they specify what should happen if a contestant fell to the ground, which is what Johnson did to avoid being hit – this action was thought by the spectators to be unsporting but was permitted by the two umpires. Before long both fighters showed signs of their opponent's attacks, with first Perrins and then Johnson suffering cut eyes and then further damage to their faces. By the fight's end Perrins' head "had scarcely the traces left of a human being",[13] according to Pierce Egan in his history of boxing. The contest lasted 62 rounds, which took a total of 75 minutes to complete, until Perrins became totally exhausted.[1][8][13][15] Tony Gee has said that

Perrins had overwhelming physical advantages but, owing to his naïvety, no clause was inserted in the articles of agreement to prevent "shifting" ... Moreover, Perrins was inexperienced in the subterfuges of the sport and found himself outwitted by his artful adversary.[8]

A celebrated champion, Jack Broughton, and his supporters had gone some way to codifying some rules in 1743, based on work by an earlier champion called James Figg, but by Johnson's time they were still very loose in interpretation and implementation.[3][16]

Perrins' supporters had gambled heavily on him because of his reputation and his advantage in size. In the event it was a major supporter of Johnson, a Thomas Bullock,[5] who gained; he won £20,000 (equivalent to £220,000 in 2010)[17] from his bets in favour of Johnson and gifted the victor £1,000.[15]

The event was recorded in The Gentleman's Magazine of that month

... a great boxing match took place ... between two bruisers, Perrins and Johnson: for which a turf stage had been erected 5 foot 6 inches high, and about 40 feet square. The combatants set-to at one in the afternoon; and, after sixty-two rounds of fair and hard fighting, victory was declared in favour of Johnson, exactly at fifteen minutes after two. The number of persons of family and fortune, who interested themselves in this brutal conquest, is astonishing: many of whom, it is proper to add, paid dearly for their diversion.[18]

The contestants received 250 guineas each, with Johnson also receiving two-thirds of the entrance takings (after costs) and Perrins receiving the other third. The net takings were £800, with the number of spectators variously stated as being 3,000 or 5,000.[1][12][15] Johnson called on Perrins and left him a guinea to buy himself a drink before leaving Banbury.[13] The fight had proved to be "one of the hardest, cleanest and most brilliant encounters that ever took place".[12]

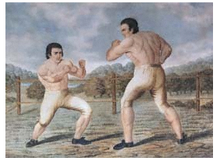

Copper medals were struck to commemorate each of the contestants. The obverse side of these contained a picture of the respective fighter; the reverse had the Latin inscription Bella! Horrida bella! (a quotation from Virgil which can be translated as wars, horrible wars)[19] and the words Strength and magnanimity in the case of Perrins, and Science and intrepidity for that of Johnson.[20] Chaloner has speculated that these may have been produced by his employers and says that they bear similarities with the work of a French die maker called Ponthon who was supplying the firm with industrial items from at least 1791.[1][21] The National Portrait Gallery holds two pictures of the Banbury fight, one being an etching published by George Smeeton in 1812,[22] and the other by Joseph Grozer in 1789.[23]

It is possible that his last fight was an 85-minute contest at Shrewsbury in July 1790. This was widely reported in the London press and that of provincial cities but was subsequently denied by newspapers more local to the event. There were unsuccessful attempts after that date to match him against Ben Bryan (sometimes known as Ben Brian, Ben Brain or Ben Bryant), who had by that time defeated Johnson.[8] Indeed, these attempts, conducted by Daniel Mendoza, did not help the cause of his employment with Boulton and Watt as the firm thought that they were a distraction and expressed concern regarding his commitment to his work.[1]

Despite the brutal nature of prizefighting, it was the opinion of boxing historian Henry Downes Miles, in his book Pugilistica, that Perrins was of a "lamb-like disposition" and an intelligent, modest, discerning, and well-liked man. He was also jolly, full of anecdotes, and ever ready to sing a tune, all of which stood him in good stead when he became a publican. Nonetheless, he was "an erratic histrionic genius, whose reckless riot ruined and extinguished his higher gifts".[15]

Work

[edit]Employed as a foreman by Boulton and Watt in Birmingham,[15] Perrins was sent around the country by the firm. In 1787 he visited Scotland, from where he reported on an invention by the Symingtons which might possibly have infringed a patent held by his employers, although Watt was disparaging of the device and its creator.[24] He installed the first Boulton and Watt stationary steam engine in Manchester, at Drinkwater's Mill in 1789.[25] He was there again by June 1791, when he spotted a copy of a Boulton and Watt product in Deansgate, one of many examples which infringed the firm's patents.[1] An engine had been built by Joshua Wrigley and used a "smokeless fire-place" similar to one patented by Boulton and Watt, although in this instance the matter was not pursued any further by them.[26]

His position in the firm was sufficiently elevated that he received business correspondence at the factory; for example, a letter to Perrins survives from October 1791, when a John Stratford sought his advice.[27] Perrins was educated and literate by the standards of his time,[8] although economic historian Eric Robinson has said that all engine-erectors needed to be literate to understand fitting instructions sent to their work site by their employers.[28]

Perrins eventually moved to Manchester permanently in 1793, to run a public house.[25] This was not an unusual thing for retired prizefighters then: they often received the proceeds of a financial collection by their supporters to enable them to buy a licence to operate such premises and "today's fighter was merely tomorrow's publican in waiting".[29] In a 1901 review of sporting prints titled The old and new pugilism, which lamented the passing of the style and the discipline of prize-fighting, "the goal of the successful pugilist was a sporting public house ... they were generally in side or back streets, where the house did not command a transient trade. Most of these sporting "pubs" had a large room at the back or upstairs, which was open one night a week (preferably Saturday), for public sparring, which was always conducted by a pugilist of some note."[30]

As well as running his public house, Perrins continued to do work for Boulton and Watt, and was an accredited engine-erector for them. In 1794[8] he was dismissed from employment by them due to his drunkenness.[25] Known for his short temper and aggressive behavior, Perrins had also been arguing with another of the firm's engineers, James Lawson, had upset customers with his manner and was accused of failing to maintain the engines in the Manchester area to a satisfactory standard. He tried to rebuff the last charge in particular, on the grounds that the firm did not pay him a retainer for the maintenance work

If you had allowed me a competency to have kept them clean, I should not be afraid of durtying (sic) my hands with doing it as some of your servants are that you send here with ruffles at hands and powdered heads, more like some Lord than an engineer. It cannot be thought that I can lose my time and neglect my own business without some consideration for it[31][1]

Even after this setback he still did some work for the firm. He tracked down and informed the firm of patent infringing copies of their engines in Leeds between 1795–1796 and probably also did the same thing subsequently in Lancashire.[32]

Scholes's Manchester and Salford Directory for 1797 shows Perrins as a "victualler and engineer", living at the Fire Engine public house, 24 Leigh Street. (The street is listed as being off George Street, which was in turn off Great Ancoats Street. It is now called George Leigh Street.)[33] His entry in the directory is an early use of the term "engineer" found in Mancunian documents, the job description at that time being a relatively new one.[34] It has been stated that at the time of his death he was running another public house, the Neptune, but historian W. H. Chaloner believes the source of the statement to be unreliable.[1][20]

In 1800 he was still doing engineering work for his former employers, who were beset with manufacturing problems and a shortage of engine-erectors.[35] He was also running his own business engaged in general millwrighting and was still called upon by various Manchester engine owners who preferred to use his services for their machine erection and maintenance needs than those of Boulton and Watt.[1] He had moved to New Street, Hanover Street and in December 1799 was appointed to the position of conductor of firemen and inspector of engines by the Manchester police commissioners, positions which effectively put him in charge of the fire brigade.[8][36][37] One source – the one considered unreliable by Chaloner – has stated that he had held the position for 20 years prior to his death.[20]

Death

[edit]Perrins' death at the age of 50 was announced on 10 December 1800 in the Annual Register, which noted him as being an "engine-worker". The Register said that

This pugilistic hero will ever be remembered for the well-contested battle he fought with the celebrated Johnson ... Perrins possessed most astonishing muscular power, which rendered him well calculated for a bruiser, to which was united a disposition the most placid and amiable. His death was occasioned by too violently exerting himself in assisting to save life and property at a fire in Manchester.[15][38]

However, this announcement of his demise was premature as in fact he died on 6 January 1801 after contracting a fever because of his exertions during the rescue, which had occurred during a huge fire that burned all through the night of 10 December.[8][21] The fire may be that described in The Annals of Manchester: "warehouses in Hodson Square were burnt down December 10, caused damages to the extent of £50,000, exclusive of the buildings".[39] On 29 December 1800 he had been awarded £20 per annum by the commissioners for "meritorious services".[1]

A memorial to Perrins and his wife, Mary (who had predeceased him by a few months), was placed at St John's Church, Byrom Street, Manchester.[21][note 1][note 2]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Although this transcription puts Perrins' age at 44, another book by the same author agrees with the consensus of opinion that he was 50 years old.[37]

- ^ St John's Church was demolished in 1931. St John's Gardens now exists on the site 53°28′40″N 2°15′10″W / 53.477914°N 2.252873°W and contains some artefacts from the church and its graveyard. In 1781, the church had been the base for one of Manchester's eight fire engines.[40]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chaloner, W. H. (October 1973). "Isaac Perrins, 1751–1801, Prize-fighter and Engineer". History Today. 23 (10): 140–143.

- ^ a b Brickley, Megan; Smith, Martin (March 2006). "Culturally determined patterns of violence: biological anthropological investigations at a historic urban cemetery". American Anthropologist. 108 (1): 171. doi:10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.163.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c Holt, Richard (1990). Sport and the British: a modern history (New ed.). Clarendon Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-19-285229-9.

- ^ a b Harvey, Adrian (2004). The beginnings of a commercial sporting culture in Britain, 1793–1850. Ashgate. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7546-3643-4.

- ^ a b "Johnson, Tom (c.1750–1797)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/59099. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Shoemaker, Robert Brink (2004). The London mob: violence and disorder in eighteenth-century England. Continuum International. ISBN 978-1-85285-373-0. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Harman, Thomas. T. (1885). Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham. Cornish Bros. p. 290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Perrins, Isaac". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60190. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Brailsford, Dennis (1988). Bareknuckles: a social history of boxing. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7188-2676-5.

- ^ Brailsford, Dennis (1988). Bareknuckles: a social history of boxing. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7188-2676-5.

- ^ a b c Pancratia, or a history of pugilism. London: W. Oxberry. 1812. pp. 89–93. hdl:2027/nyp.33433066623012.

- ^ a b c d "Tom Johnson's Greatest Fight". St Joseph Gazette. Vol. 121, no. 44. Missouri. 13 February 1910. p. 26. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Egan, Pierce (January 1999). Boxiana (Facsimile of 1830 ed.). Elibron Classics. pp. 97–100. ISBN 978-1-4021-8128-3.

- ^ Anon. (One of the Fancy) (December 1819). "Boxiana; or sketches of pugilism". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 6: 281–282. hdl:2027/uc1.32106019922423.

- ^ a b c d e f Miles, Henry Downes (1906). Pugilistica: the history of British boxing. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: John Grant. pp. 60–63.

- ^ Kenyon, James W. (1961). Boxing History. Chatham: W & J McKay. p. 9.

- ^ "Historical UK inflation and price conversion". Safalra. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ Sylvanus Urban (pseud.) (October 1789). "Intelligence from Ireland, Scotland and the Country Towns: Country News". The Gentleman's Magazine. 59 (Part 2). London: David Henry: 947–948. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010955006.

- ^ Stone, Jon R. (2005). The Routledge dictionary of Latin quotations: the illiterati's guide to Latin maxims, mottoes, proverbs and sayings. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-415-96909-3.

- ^ a b c Heywood, Nathan (1909), "Local and personal medals relating to Manchester", Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, XXVII: 51–52

- ^ a b c Procter, Richard Wright (1880). Memorials of bygone Manchester. Palmer & Howe. p. 274.

- ^ "Tom Johnson (Thomas Jackling); Isaac Perrins (Smeeton)". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Tom Johnson (Thomas Jackling); Isaac Perrins (Grozer)". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Smiles, Samuel (1865). Lives of Boulton and Watt. London: John Murray. p. 435. hdl:2027/nyp.33433082344486.

- ^ a b c Robinson, Eric; Musson, Albert Edward (1969). Science and Technology in the industrial revolution. Manchester University Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-7190-0370-7.

- ^ Robinson, Eric; Musson, Albert Edward (1969). Science and Technology in the industrial revolution. Manchester University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-7190-0370-7.

- ^ Band, Stuart R. (1983). "The steam engines of Gregory mine, Ashover" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society. 8 (5). PDMHS: 280–282.

- ^ Robinson, Eric H. (March 1974). "The Early Diffusion of Steam Power". The Journal of Economic History. 34 (1). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association: 94. doi:10.1017/s002205070007964x. JSTOR 2116960. S2CID 153489574.(subscription required)

- ^ Collins, Tony; Vamplew, Wray (2002). Mud, sweat and beers: a cultural history of sport and alcohol. Berg. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-85973-558-9.

- ^ Austin, Alf. (March 1901). "The old and new pugilism". Outing. 37. New York and London: The Outing Publishing Company: 682–687. hdl:2027/mdp.39015050616781. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ H.W. Dickinson and R. Jenkins, James Watt and the Steam Engine The Memorial Volume Prepared for the Committee of the Watt Centenary Commemoration at Birmingham 1919 (London: Encore Editions reprint, 1989)

- ^ Robinson, Eric; Musson, Albert Edward (1969). Science and Technology in the industrial revolution. Manchester University Press. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-7190-0370-7.

- ^ Scholes's Manchester and Salford Directory (2nd ed.). 1797. p. 165.

- ^ Robinson, Eric; Musson, Albert Edward (1969). Science and Technology in the industrial revolution. Manchester University Press. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-7190-0370-7.

- ^ Robinson, Eric; Musson, Albert Edward (1969). Science and Technology in the industrial revolution. Manchester University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-7190-0370-7.

- ^ Procter, Richard Wright (1880). Memorials of bygone Manchester. Palmer & Howe. p. 291.

- ^ a b Procter, Richard Wright (1862). Our Turf, Our Stage, and Our Ring. Dinham & Co. p. 75.

- ^ "Tales of the Turf". The New Zealand Observer. Vol. 7, no. 347. 1 August 1885. p. 14.

- ^ Axon, William Edward Armytage (1885). The Annals of Manchester. John Heywood. p. 128.

- ^ Harland, John, ed. (1866). Collectanea relating to Manchester and its neighbourhood, at various periods. Vol. 68. Printed for the Chetham Society. p. 137.

Further reading

[edit]The following are a selection from the catalogue of the Boulton and Watt Collection held at Birmingham Central Library in so far as they relate to Isaac Perrins.

- "Reel 243 MS 3147/3/286-404" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 244 MS 3147/3/286-404" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 245 MS 3147/3/286-404" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 246 MS 3147/3/286-404" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 251 MS 3147/3/414 1795–1798" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 251 MS 3147/3/417 1795–1798" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 253 MS 3147/3/421 1795–1798" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.

- "Reel 258 MS 3147/3/430 1787–1798" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications.