Messe des pauvres

The Messe des pauvres (Mass for the Poor) is a partial musical setting of the mass for mixed choir and organ by Erik Satie. Composed between 1893 and 1895, it is Satie's only liturgical work and the culmination of his "Rosicrucian" or "mystic" period. It was published posthumously in 1929.[Note 1][Note 2] A performance lasts around 18 minutes.

History

[edit]In the early 1890s, Satie's fascination with medieval Catholicism, Gothic art and Gregorian chant led him to explore religious influences in his life and music. At first he was drawn to Joséphin Péladan's Rose + Croix movement, for which he acted as official composer from 1891 to 1892, and after breaking with Péladan he associated with the occultist writer Jules Bois, publisher of the religious esoteric journal Le coeur. At the same time he was immersed in a bohemian lifestyle as a pianist at Montmartre cabarets, where his already eccentric behavior took on a growing penchant for buffoonery and exhibitionism.[2]

This paradox came to a head in October 1893 when Satie founded his own mock religious sect, the Église Métropolitaine de l'Art de Jésus Conducteur (Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor), with himself as High priest, choirmaster, and sole member. It was a spoof of the flamboyant Péladan, whose Rose + Croix creed ("the transformation of society through art") and habit of "excommunicating" his critics in bombastic letters to newspapers Satie gleefully adopted.[3] He carried the charade into his daily existence, dressing in monkish robes and referring to his tiny room at 6 Rue Cortot as his abbatiale (abbey). "[Satie] liked to affect the unctuous manners of a priest," his friend Francis Jourdain recalled. "They suited him so well, he played his part so accurately - being careful not to overdo things - that the question arose as to whether a slightly false air was not innate in him."[4]

Against this background, Satie's motives for writing the Messe des pauvres - the sole composition linked to his church - are obscure. Originally entitled Grande Messe de l'Eglise Métropolitaine d'Art,[5] it was his most ambitious work to date, although there was no evident prospect of having it performed.[6] Satie authorities Ornella Volta and Robert Orledge believe he conceived the mass to occupy his mind following his recent breakup with the painter Suzanne Valadon, which had left him emotionally devastated.[7][8] At the midpoint of their turbulent six-month affair in March 1893, Satie had composed his Danses gothiques as a "Novena for the great calm and profound tranquility of my Soul";[9] similarly, the first mass movement he completed (in late 1893) was the Prière pour le salut de mon âme ("Prayer for the salvation of my soul").[10] It is unknown how the mass assumed its final title Messe des pauvres. The texts Satie chose make no reference to the poor at large, giving further weight to speculations that, impoverished as he was, he essentially wrote the mass for his own solace.[11]

In 1895, a substantial cash gift from a friend enabled Satie to publish a series of tracts in which, under the guise of his church, he criticised those of whom he disapproved. Portions of the Messe des pauvres appeared in two of them: an extract from the Commune qui mundi nefas in a pamphlet of the same name (January 1895), and the complete Dixit Domine - calligraphed in faux Gregorian notation by Satie - in the brochure Intende votis supplicum (March 1895).[12] The only contemporary account of the mass is an article by the composer's brother, Conrad Satie, published in the June 1895 issue of Le coeur. He described it as a work in progress, humbly scored for organ and a choir of children's and men's voices. "This mass is music for the divine sacrifice, and there will be no part for the orchestras which, I'm sorry to say, find their way into most masses," he wrote.[13] He also made an intriguing statement about its structure: "Between the Kyrie and the Gloria a prayer is inserted called Prière des orgues." The Gloria movement was not found in Satie's posthumous papers and is considered lost.

Soon after his brother's article appeared, the unpredictable Satie lost interest in his church, the mass, and in composition altogether. That same month he exchanged his robes and religious affectations for the seven identical sets of corduroy suits that would come to define his "Velvet Gentleman" phase,[14] and for the better part of two years he wrote nothing. In his next important work, the Pièces froides for piano (1897), Satie revisited the pre-Rose + Croix style of his Gnossiennes and turned his back on the mystical-religious influences he would later dismiss as "musique à genoux" ("music on its knees").[15] The mass was not performed during his lifetime.

After Satie's death in 1925, his friend and music executor Darius Milhaud brought the forgotten manuscript of the Messe des pauvres to light. Three of the movements (the Prière des orgues, Commune qui mundi nefas, and Prière pour le salut de mon âme) were premiered by organist Paul de Maleingreau at the Concerts Pro Arte in Brussels, Belgium, on May 3, 1926.[16] An early complete performance was led by Olivier Messiaen at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité, Paris on March 14, 1939.[17] The work was first recorded in 1951.

Setting

[edit]

The published score presents the mass in seven movements:[18][19]

- 1. Kyrie eleison (Lord, have mercy)

- The most substantial movement and the only surviving section set to the Ordinarium. A lengthy organ prelude establishes six motifs inspired by the words "Kyrie eleison", which are then alternately sung by low and high voices

- 2. Dixit Domine (The Lord said)

- The opening words of Psalm 110 (Vulgate 109), the first psalm of Vespers on Sundays and major feast days, sung in unison by the choir. The original publisher garbled the text, which should read "Dixit Dominus Domino meo / Sede a dextris meis"[20]

- 3. Prière des orgues (Organ Prayer)

- Organ solo

- 4. Commune qui mundi nefas (Thou, that Thou mightst our ransom pay)

- Organ solo. The title is Line 9 of the hymn Creator alme siderum, used at Vespers during Advent[21]

- 5. Chant ecclésiastique (Ecclesiastical Chant)

- Organ solo, on two-stave score for the manuals alone. "Chant ecclésiastique" is (or was) a generic French term for Gregorian plainsong

- 6. Prière pour les voyageurs et les marins en danger de mort, à la très bonne et très auguste Vierge Marie, mère de Jésus (Prayer for travellers and sailors in danger of death, to the very good and very august Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus)

- Organ solo, manuals only

- 7. Prière pour le salut de mon âme (Prayer for the salvation of my soul)

- Organ solo, manuals only

As Conrad Satie noted, the work was intended for organ, children's choir and men's voices, but as the score designates only basses and dessus (high) vocal parts a mixed adult choir is commonly used in performance. The choral writing is strongly reminiscent of plainsong.

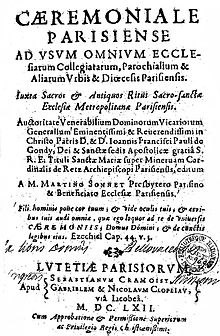

In its existing state - two choral movements followed by a series of organ solos - the Messe des pauvres does not conform to any liturgical tradition; but this is partly a result of circumstance. Satie's probable model was the organ mass,[22] in which instrumental pieces (versets) were composed to replace sections of the Ordinarium or Vespers (evening service) that were otherwise chanted or sung. These were performed in alternatim with the chorus and usually improvised by the organist.[23] The genre was most prevalent in France from the mid-1600s. While the French Catholic church attempted to regulate the alternation of chant and organ in mass performance, beginning with the Caeremoniale Parisiense of 1662, its edicts were commonly ignored as regional parishes established their own alternatim mass traditions.[24] Famous Parisian organists such as Claude Balbastre and Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély introduced dances and other secular influences into their liturgical improvisations.[25][26] Pope Pius X would ban the alternatim practice altogether in 1903,[27] but in the meantime the flexibility the French variety offered can only have appealed to Satie, who was never content with rigid musical forms of any kind.

Then there is the loss of the Gloria, the original fourth movement of the Messe des pauvres. Its inclusion would have made the work acceptable for use in a church service as a missa brevis, albeit a rather unorthodox one.[28]

Examining the score in the 1980s, Robert Orledge found "sprawling uncertainties" in its "assortment of movements" and believed the mass was left unfinished.[29] Sketches of two or three pieces from Satie's notebooks of the period may relate to the work, but whether he planned to expand it or to provide plainsong-like text settings for some of the organ solos must remain speculative.[30][31]

The mysterious stasis of the music, and Satie's unique reimagining of medieval modes with some of his most innovative harmonic writing,[32] give the mass a haunting, timeless quality that is very effective in performance.[33] Wilfrid Mellers saw in the works of the mystic period "a necessary step in Satie's creative evolution...technically they link up with plainsong and organum...not in any antiquarian spirit but rather because Satie saw in the impersonality, the aloofness, the remoteness from all subjective dramatic stress of this music qualities which might, with appropriate modifications, approximate to his own uniquely lonely mode of utterance."[34]

Reception

[edit]An anomaly in both Satie's output and in liturgical music in general, the Messe des pauvres remains one of his lesser-known large-scale works. His first biographer, Pierre-Daniel Templier (1932), was almost apologetic over Milhaud's decision to publish the score, even though he found "real gems" in some of the movements.[35] Nevertheless, it has long had its advocates among Satie devotees. There are several arrangements, from musicians as diverse as David Diamond (1949), Marius Constant (1970) and Louis Andriessen (1980). Edgard Varèse enthused, "I've always admired Satie and above all the Kyrie of the Messe des pauvres, which has always made me think of Dante's Inferno and strikes me as being a kind of pre-electronic music..."[36] And Virgil Thomson defined the inscrutable qualities of the mass thus: "It does not invoke the history of music. Its inner life is as independent of you as a Siamese cat."[37]

Recordings

[edit]For chorus and organ:

Marilyn Mason (organ) and chorus directed by David Randolph (Esoteric, 1951, reissued by Él, 2007), Gaston Litaize and the Choeur René Duclos (EMI, 1974), Hervé Désarbre and the Ensemble Vocal Paris-Renaissance (Mandala, 1997)

Transcriptions and arrangements:

For two organs and choir: Elisabeth Sperer, Winfried Englhardt (organs), Münchner Madrigalchor (FSM, 1990); for organ only: Christopher Bowers-Broadbent (ECM, 1993); for solo piano: Bojan Gorišek (Audiophile Classics, 1994), Alessandro Simonetto (OnClassical, 2022); for orchestra: Gerard Schwarz conducting the Seattle Symphony, arrangement by David Diamond, (Koch Schwann, 1996)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Confirmed by Satie biographer Pierre-Daniel Templier in 1932, and by Darius Milhaud (who oversaw the publication) in his memoirs. See Templier, "Erik Satie", MIT Press, 1969, p. 85, translated from the original French edition published by Rieder, Paris, 1932; and Milhaud, "Notes without Music", Denis Dobson Ltd., London, 1952, p. 150.

- ^ In 1998, Erich Schwandt elucidated the early publication history of the Messe, including erroneous claims that it was first issued in 1920, though this earlier date still appears in a number of sources. See Schwandt, "A New Gloria for Satie's Messe Des Pauvres", Canadian University Music Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1998, p. 38, note 1, and p. 40, note 11.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ "A New Gloria for Satie's Messe des Paures" (PDF).

- ^ Patrick Gowers and Nigel Wilkins, "Erik Satie", "The New Grove: Twentieth-Century French Masters", Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1986, p. 131. Reprinted from "The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians", 1980 edition.

- ^ Steven Moore Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian: From Cabaret to Concert Hall", Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 162-163, 170-171.

- ^ Quoted in Robert Orledge, "Satie Remembered", Faber and Faber Ltd., 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Robert Orledge, "Satie the Composer", Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 352, note 16.

- ^ Schwandt, "A New Gloria for Satie's Messe Des Pauvres", p. 38.

- ^ Ornella Volta, "Satie Seen Through His Letters", Marion Boyars Publishers, New York, 1989, p. 48.

- ^ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 211.

- ^ "Danses Gothiques - Sheet Music" (PDF). imslp.eu.

- ^ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 279.

- ^ "Messe des pauvres". AllMusic. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ Facsimiles of both scores appear in Nigel Wilkins (ed.), "The Writings of Erik Satie", Eulenburg Books, London, 1980, pp. 38-42.

- ^ Conrad Satie, "Erik Satie", Le coeur, June 1895, pp. 2-3. Quoted in Robert Orledge, "Satie Remembered", Faber and Faber, London, 1995, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", pp. xxiii, xxiv.

- ^ Rollo H. Myers, "Erik Satie", Dover Publications, Inc., NY, 1968, p. 73. Originally published in 1948 by Denis Dobson Ltd., London.

- ^ "années 10/20 270 concerts Ballets suédois, Soirées de Paris, Ballets russes… - Roger Désormière (1898-1963)". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ Peter Hill, Nigel Simeone, "Messiaen", Yale University Press, 2005, p. 82.

- ^ "Messe Des Pauves Sheet music" (PDF). imslp.org.

- ^ According to Robert Orledge, Satie listed the opening organ solo (Prelude) as a separate movement, even though it serves to introduce the material of the Kyrie which follows without a break. With the missing Gloria the mass would have had nine movements. See Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 279.

- ^ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 280.

- ^ "Creator alme siderum". www.preces-latinae.org.

- ^ Douglas Earl Bush, Richard Kassel, "The Organ: An Encyclopedia", Psychology Press, 2006, pp. 384-385.

- ^ Bush and Kassel, "The Organ: An Encyclopedia", pp. 384-385.

- ^ Barrett-Benson, Laurie. ""The Effects of the Revolution on the Organ Mass in France"" (PDF). California State University Los Angeles.

- ^ David Ponsford, "French Organ Music in the Reign of Louis XIV", Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 188.

- ^ Barrett-Benson, "The Effects of the Revolution on the Organ Mass in France".

- ^ Joseph Peter Swain, "The A to Z of Sacred Music", Rowman & Littlefield, 2010, p. 157.

- ^ Schwandt, "A New Gloria for Satie's Messe Des Pauvres", p. 39.

- ^ Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 164 and p. 352, note 16.

- ^ The sketches are titled Spiritus sancte deus miserere nobis, Harmonies de Saint-Jean, and Modéré. See Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 280.

- ^ Schwandt, "A New Gloria for Satie's Messe Des Pauvres", pp. 39, 44.

- ^ "Erik Satie: Musique de la Rose-Croix; Pages mystiques; Uspud - Richard Cameron-Wolfe, Bojan Gorisek". AllMusic. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ Richard Langham Smith, Caroline Potter (ed.), "French Music Since Berlioz", Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Wilfrid H. Mellers, "Erik Satie and the 'Problem' of Contemporary Music", Music & Letters 23 (1942), p. 212.

- ^ Pierre-Daniel Templier, "Erik Satie", MIT Press, 1969, p. 85. Translated from the original French edition published by Rieder, Paris, 1932.

- ^ Ornella Volta, "Satie Seen Through His Letters", Marion Boyars Publishers, New York, 1989, p. 106.

- ^ Quoted by Alex Ross, "Critic's Notebook; Of Mystics, Minimalists and Musical Miasmas", New York Times, November 5, 1993. Thomson was one of Satie's most influential champions in the United States. The Messe Des Pauvres was performed at his memorial service in 1989.