Zrenjanin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

Zrenjanin

| |

|---|---|

| City of Zrenjanin | |

|

From top: Freedom Square with Zrenjanin City Hall and Cathedral of St. John of Nepomuk, National Museum, Zrenjanin Vodotoranj, Dr Zoran Djindjic Square, Small Bridge, King Aleksandar I Karadjordjevic main street, Reformed Church | |

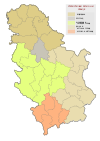

Location of Zrenjanin within Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 45°23′0″N 20°23′22″E / 45.38333°N 20.38944°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| District | Central Banat |

| Settled by Roxolani | 3rd century AD |

| Founded | 10 July 1326 |

| City status | 6 June 1769 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Simo Salapura (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Rank | 3rd in Serbia |

| • Urban | 193.03 km2 (74.53 sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 1,325.88 km2 (511.93 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 76 m (249 ft) |

| Population (2022 census)[1] | |

| • Rank | 11th in Serbia |

| • Urban | 67,129 |

| • Urban density | 350/km2 (900/sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 105,722 |

| • Administrative density | 80/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Zrenjaninci (sr) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 23000 |

| Area code | +381(0)23 |

| ISO 3166 code | SRB |

| Car plates | ZR/ЗР |

| Website | zrenjanin |

Zrenjanin (Serbian Cyrillic: Зрењанин, pronounced [zrɛ̌ɲanin]; Hungarian: Nagybecskerek; Romanian: Becicherecu Mare; Slovak: Zreňanin; German: Großbetschkerek) is a city and the administrative center of the Central Banat District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The city urban area has a population of 67,129 inhabitants, while the city administrative area has 105,722 inhabitants (2022 census data). The old name for Zrenjanin is Veliki Bečkerek or Nagybecskerek as it was known under Austria-Hungary up until 1918. A thousand Catalans founded on 1735 New Barcelona in a place which is now the suburb of Dolja within Zrenjanin, exiled from the War of the Spanish Succession. After World War I and the liberation of Veliki Bečkerek the new name of the city was Petrovgrad, in honor of His Majesty King Peter I the Great Liberator, the King of Serbia and the King of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Zrenjanin is the 2nd largest city in the Serbian part of the Banat geographical region, and the third largest city in Vojvodina (after Novi Sad and Subotica). The city was designated European city of sport.

Name

[edit]

The city was named after Žarko Zrenjanin (1902–1942) in 1946 in honour and remembrance of his name. One of the leaders of the Vojvodina communist Partisans during World War II, he was imprisoned and released after being tortured by the Nazis for months, and later killed while trying to avoid recapture.[citation needed] The former Serbian name of the city was Bečkerek (Бечкерек) or Veliki Bečkerek (Велики Бечкерек). In 1935 the city was renamed to Petrovgrad (Петровград) in honor of king Peter I of Serbia. It was called Petrovgrad from 1935–46. In Hungarian, the city is known as Nagybecskerek, in German as Großbetschkerek or Betschkerek, in Romanian as Becicherecul Mare or Zrenianin, in Slovak as Zreňanin, in Rusin as Зрењанин, in Croatian as Zrenjanin, and in Turkish as Beşkelek (meaning five melons) or Beçkerek.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Prehistory

[edit]

Prehistory can be divided into the Palaeolithic – Old Stone Age and the Neolithic – New Stone Age. In Zrenjanin's regions no archaeological sites of the Palaeolithic have been found. The only exception makes the discovery of mammoth’s head and other bones found on the banks of Tisa River near Novi Bečej in the year 1952. The discovered archaeological sites, however, indicate that these regions had already been inhabited in the early Neolithic period about 5000 years BC. The most important archaeological site from this period is so-called Krstić tumulus, near Mužlja, about 10 km (6 mi) away from Zrenjanin. Here were found the ceramics, with interesting ornaments. Beside the brewery ground have been found rough, with coloured fine ceramics, ornaments (Starčevo culture). The middle Neolithic appeared in our area as Vinča and Potisje culture, in the down course of the Tisa River. What makes this area important is the fact that the influence of two parallel cultures flew through it at the same time. The Iron Age has not been enough explored yet. A few regions with some archaeological materials from the Iron Age have been found: in the residential area Šumica a tip of a spear was found and near the oil factory, pieces of ceramics from the Bronze Age were discovered.

At the beginning of the common era,[clarification needed] this area was settled by many native tribes, but also by many newcomer tribes: the Illyrians, the Celts, the Goths, the Geths, the Sarmatian and Jazghs. In the end of the third century and in the middle of the fourth century, in the area of Zrenjanin and its surroundings, the Sarmatian tribe Roxolani appeared. From this period a Sarmatian’s graveyard has been found in a city residential district, near the railroad bridge. Finally in the necropolis, not far from Aradac, “Mečka”, more than 120 graves, which date from the end of the sixth and the beginning of the seventh century, have been excavated in 1952.

Middle Ages

[edit]

The first historical records mentioning Zrenjanin (Bečkerek) date from the 14th century, the time when Charles I, King of Hungary and Croatia (1301–1342), used to visit Banat and spend time in his capital Timișoara. (Near today's Zrenjanin a coin was found with the inscription "Charles I".) Many noblemen came with the King, including the powerful Imre Becsei. The areas where Becsei settled down were named for him, “Bechereki” and “Beche” (Novi Bečej). The oldest written records of Bečkerek date from Budim Capitulum's document of collecting the Pope's tens taxes in 1326, 1331 and 1332. Judging by the size of the taxes, Bečkerek of 1330s was an average village. The first settlers were the landless Hungarian peasants. There were the Serbs in Banat, too. During the reign of Louis I of Hungary (1343–1382), more Serbs migrated to the area from the south, and with them many Orthodox priests.

After the Turkish victory at the battle of Nicopolis (1396) the Hungarian King Sigismund (1387–1437) was considering defending the territory settled by the Serbs, and he is known to have visited Bečkerek on September 30, 1398. The town was granted to Stefan Lazarević at the end of the 1403. The despot became the vassal of the Hungarian King; but he got Bečkerek and the title of the Great Head of the Torontál County.

Ottoman period

[edit]

The Hungarian King Ferdinand appointed friar Djordje Martinović, a commander of his forces, to defend the town from the Ottomans. Hungary was attacked by 80,000 Ottoman soldiers under the command of Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. On 15 September 1551, the siege of the town Bečej was raised and the town was taken after four days. On 24 September, the Bečkerek fortress was besieged. Many people left town earlier and with few defenders the town couldn't be defended and those eighty, who left surrendered the next day. Malković was appointed the lord of Bečkerek. After the Ottomans had taken Timișoara in 1552, Banat became a special province, the Temeşvar Eyalet, which was made up of several sanjaks, including the Sanjak of Beçkerek.

During Ottoman occupation, the sanjak had a military administration. Due to good behaviour of the rayah, the inhabitants were exempt from war taxes. During the 165 years of Ottoman rule, Bečkerek consisted of two separate settlements: the settlement of Bečkerek and the village of Gradnulica. The town was divided into two parts, a Turkish and a Serbian. The Turkish part was fenced and closed, while the Serbian one was open. On the main square there was a large mosque built and inside the fortress there was a little one. There was a Turkish bath, and around it there were about twenty stores. Gradnulica was a disorderly village, whose centre was approximately on the crossroad of the present streets Sindjelićeva and Djurdjevska. Prior to Ottoman occupation, the citizens were Serbs and Hungarians. At the end of the 18th century, there were about fifty Turkish families. According to the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), the Temeşvar Eyalet, including Bečkerek, stayed under Ottoman rule, while bordering territories once again came under the Military Frontier. After the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–18 Bečkerek went under Habsburg rule.

Habsburg and Austrian period (1718–1914)

[edit]

As a crown province, Banat belonged directly to the Vienna court. The first governor, appointed by the Emperor, was Count Claudius Mercy. By the imperial edict on 12 September 1718, Banat was divided into 13 districts, with the main administration in Timișoara at its head. The District of Banat included a few settlements: Idjoš, Arač, Bečej, Itebej, Elemir, Ečka and Aradac. The first chief of this district was Titus Vespanius Slucki. After the Turkish forces and Turks families had withdrawn, the land was left devastated without labour, which could till the soil and paid taxes. That's why the Austrian court tried to settle Banat as soon as possible.

The colonization lasted from 1718–24, when the town was settled mostly by Germans, but the Serbs never stopped arriving. The military frontier in Potisje was displaced. In the following years Italians, Frenchmen, Romanians arrived and then the Catalans from Barcelona, who escaped the repression after the War of the Spanish Succession and settled in a place which is now the suburb of Dolja within Zrenjanin. The town was called New Barcelona. But the life was difficult in this marsh area with many contagious diseases, so many died and others left.

In the summer of 1738 there was the great plague. The Count Mersy wanted to turn marshes into fertile soil and he began to regulate the Begej River. In the middle and down course of the river a long canal was built, to make the river traffic possible between Bečkerek and Timișoara. On the first of November 1745 Sebastian Krazeisen began to make beer in the first brewery and that meant the first start of the industrialization. In the same year the first Serb's school was mentioned.

On 6 June 1769, Maria Theresa granted the Community of Great Bečkerek, the privilege of becoming the trading centre. By this privilege the whole social-economic life of the former Bečkerek was regulated and it got the status of the town. In 1769 the first hospital was built. In 1779, by the new organization of Torontál County, Bečkerek became its centre. The city was briefly restored to Ottoman administration from 1787 to 1788 during Austro-Turkish War (1787–91).

During the 18th century it developed into thriving economic and cultural centre, but the great fire destroyed a large portion of the town in 1807. The town was soon rebuilt. The fire came from the brewery, on 30 August 1807. After the fire a new regulation of streets had been done, houses had been built from stronger materials, roads had been rebuilt. The river traffic was especially intensive. The theatre building with an attractively decorated hall was built in 1839. In 1846 the Grammar School was opened and in 1847 the first printing shop.

The 1848–49 Revolutions impacted Bečkerek. The Serbs revolted, aiming for autonomy within the Austrian Empire. At the May Assembly (13–15 May 1848), the Serbian Vojvodina was proclaimed, including most of what is today Vojvodina. Serbs from Bečkerek participated in the uprising against Hungarian authority (which refused Serb rights) and from 26 January to 29 April 1849 the town was under Serb rebel control. In 1849, the town became part of the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar until 1860.

Although that time was known in history as a period of Bach's absolutism, the second part of the 19th century brought the town new developing benefits. New industrial facilities and handicraft stores were opened in every part of the town. Late 19th and early 20th century was progressive period for Veliki Bečkerek. Railway arrived in 1883, while post office was opened back in 1737.

World War I and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

[edit]

After the Sarajevo assassination, more than 30 citizens of Bečkerek were accused by the Austria-Hungary’s authorities of high treason. Among them was Dr Emil Gavrila, who together with Svetozar Miletić and Jaša Tomić, worked very hard on the cultural and social strengthening of Serbs. Those Serbs recruited in the Austria-Hungary's army began to desert to avoid having to fight their own people. 7,000 of them formed volunteer detachments (people were from Banat and Srem) at the Eastern front and fought at Dobruja, but 79 fought on the Salonice front. After years, the Serbs forces made a breakthrough of the Salonice front in 1918 and began to liberate their own country. The First Army in command of Vojvoda Petar Bojović freed Belgrade on 1 November 1918 and began to occupy Vojvodina.

On 17 November, Serbian army arrived at Veliki Bečkerek. On 31 October 1918, the Serb Chamber of People of the town founded in the war conditions, as a temporary authority with Dr Slavko Župunski at its head. Serb army, the infantry iron regiment “Prince Mihajlo” and the infantry brigade with Colonel Dragutin Ristić in command came into the town on 17 November 1918. A few days after Vojvodina had been occupied, its provinces were attached to the Kingdom of Serbs and on December 1, 1918, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was founded, as the first South Slavic state. The town of Veliki Bečkerek became the administrative centre of Torontal-Tamiš County, and after its repealing, the town became the headquarters of District Office. In 1929 the town became part of the Danube Banovina. By the Town Council decision made on 29 September 1934, and confirmed by the Town Authority on 18 February 1935, the town was renamed Petrovgrad, after the king Peter I.

Second World War and SFR Yugoslavia

[edit]

After the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had capitulated on 18 April 1941, and Nazi Germany occupied the country, the German Forces came into Petrovgrad. The authority in Banat had domestic Germans – Volksdeutsche, who immediately started to confiscate Jews' property and arrested patriots. The town was renamed Great Bečkerek and it was the headquarters of the occupation authority for Banat (1941–44), headed by Juraj Špiler, and a concentration camp in Cara Dušana Street. The Petrovgrad Synagogue was razed brick by brick by order of Jurgen Wagner.

The camp existed for almost two years and thousands of people passed through it. In town there were many underground groups supported by the Communist Party, which fought the German occupiers and the Germans made reprisals. On 2 October 1944, the Red Army Forces came into town, and, after a short fight, took command of most vital public buildings. The following day the first meeting on National Liberation Committee for the town Petrovgrad was held. Eight members of the national liberation resistance, from the town and its surroundings were announced National Heroes: Žarko Zrenjanin, Svetozar Marković Toza, Pap Pavle, Stevica Jovanović, Servo Mihalj, Nedeljko Barnić Žarki, Boško Vrebalov, and Bora Mikin Marko.

During World War II, the town infrastructure was kept almost saved. Except in the final fights for the town, there were no war actions on the territory of the town. The Germans tried to damage and destroy some industrial buildings, but it was prevented. Only Anau-Winkler's mill and the monumental Jewish synagogue in the centre of the town were destroyed. After World War II important social-political changes were made in the country, which, of course, had their influence on the development of Zrenjanin, newly named in 1946. In August 1945 the Agriculture Reform Act came into force, in June 1950 the Worker Self-Management Act, in 1959 the first direct urban plan of the town development, which indicated the urbanism-economic development of the town, was passed.

The development, in the first after war decade, was directed by the directive plans, which were based on the principles of socialist economy in which the most important industrial branches were industry and agriculture. By the 1980s many people left their villages and moved into towns which brought many changes in the social, educational and ethnic structure of the town. There was permanently shortage of housing. That is why many new parts of the town and many new apartment buildings were built. Zrenjanin became an important agricultural, industrial, cultural and sport centre, at the time Zrenjanin was one of the most powerful industrial centers of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia led by Tito.

After 1991

[edit]

The town's development has always been strongly affected by the social-economic circumstances reflecting the State surroundings that Zrenjanin found in. At the beginning of 1990s, when the war broke out on the territory of the former Yugoslavia, and the country was falling apart, it led to rather hard social and economic crisis in this area, all that caused an economic stagnation, unemployment, large migrations of refugees from the former Yugoslav Republics: Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The town experienced the first political changes by the introducing of multiparty system at the end of 1996 when the local government was ruled by the coalition Zajedno (Together) and in 2000 by the coalition Democratic opposition of Serbia. On 24 March 1999, the NATO bombing of Serbia began but the town was not targeted. Life in the town was quite normal, in spite of the dangerous situation elsewhere in the country.

In the first years after the end of war activities the Town and its citizens have been adjusting to new economic and social-economic conditions, known as transition. Instead of previous large economic combines and companies plenty of new flexible private enterprises are established and foreign capital is starting to flow in Zrenjanin. New industrial and work and residential zones are formed and the Town's General Plan 2006-2026 and Sustainable Development Strategy 2006-2013 are made and approved. At the end of 2007, introducing a new national territorial organisation followed by necessary legislation, the Municipality of Zrenjanin has been upgraded to an administrative and territorial status of a city.

In 2004, the town's tap water was deemed unsafe for consumption due to high levels of arsenic. As of 2022, the ban remains in place.[2]

Geography

[edit]Zrenjanin is situated on the western edge of the Banat loess plateau, at the place where the canalized River Begej flows into the former water course of the River Tisa. The territory of the city is predominantly flat country. The City of Zrenjanin is situated at a longitude of 20°23’ east and a latitude of 45°23’ north, in the center of the Serbian part of the Banat region, on the banks of the Rivers Begej and Tisa. The city is located at 80 meters above sea level.

Zrenjanin is around 70 kilometres (43 mi) away from Belgrade, and about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Novi Sad, which is also the distance to the present border with the European Union (Romania), which makes its position a particularly important transition center and potential resource in the directions north–south and east–west.

Inhabited places

[edit]

The city administrative area includes the following villages:

Neighbourhoods in Zrenjanin

[edit]- Bagljaš

- Berbersko

- Bolnica

- Brigadira Ristića

- Downtown

- Četvrti Jul

- Čontika

- Dolja

- Dunavska

- Duvanika

- Gradnulica

- Lesnina

- Mala Amerika

- Mužlja, a former village, joined with Zrenjanin in 1981

- Nova Kolonija

- Putnikovo

- Ruža Šulman

- Šećerana

- Šumica

- Zeleno Polje

Climate

[edit]

The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is Cfa (Humid Temperate Climate).[3]

The average temperature for the year in Zrenjanin is 12.1 °C (53.8 °F). The warmest month, on average, is July with an average temperature of 22.9 °C (73.2 °F). The coolest month on average is January, with an average temperature of 0.7 °C (33.3 °F).

The highest recorded temperature in Zrenjanin is 42.9 °C (109.2 °F), which was recorded in July. The lowest recorded temperature in Zrenjanin is −27.5 °C (−17.5 °F), which was recorded in February.

The average amount of precipitation for the year in Zrenjanin is 597.1 mm (23.5 in). The month with the most precipitation on average is June with 84.3 mm (3.3 in) of precipitation. The month with the least precipitation on average is February with an average of 33.7 mm (1.3 in). There are an average of 126.8 days of precipitation, with the most precipitation occurring in May with 12.4 days and the least precipitation occurring in August with 7.5 days.

| Climate data for Zrenjanin (1991–2020, extremes 1961–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

42.9 (109.2) |

40.4 (104.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

31.9 (89.4) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

42.9 (109.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.5 (85.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.3 (27.9) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.3 (−17.1) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

5.4 (41.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−23.1 (−9.6) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.6 (1.44) |

33.7 (1.33) |

35.1 (1.38) |

40.9 (1.61) |

61.3 (2.41) |

84.3 (3.32) |

59.4 (2.34) |

50.9 (2.00) |

54.9 (2.16) |

49.7 (1.96) |

43.6 (1.72) |

46.7 (1.84) |

597.1 (23.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12.2 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 12.4 | 11.8 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 12.3 | 126.8 |

| Average snowy days | 6.1 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 21.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.5 | 78.7 | 69.7 | 65.6 | 66.1 | 67.6 | 65.3 | 64.4 | 70.3 | 75.4 | 80.5 | 86.1 | 72.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.9 | 104.0 | 164.1 | 206.5 | 248.7 | 276.3 | 307.5 | 292.9 | 209.4 | 165.0 | 98.1 | 61.2 | 2,204.6 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[4][5] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 100,364 | — |

| 1953 | 102,844 | +0.49% |

| 1961 | 115,692 | +1.48% |

| 1971 | 129,837 | +1.16% |

| 1981 | 139,300 | +0.71% |

| 1991 | 136,778 | −0.18% |

| 2002 | 132,051 | −0.32% |

| 2011 | 123,362 | −0.75% |

| 2022 | 105,722 | −1.39% |

| Source: [6][1] | ||

According to the 2022 census, the total population of the city of Zrenjanin was 105,722.

Ethnic groups

[edit]Settlements with Serb ethnic majority are: Zrenjanin, Banatski Despotovac, Botoš, Elemir, Ečka, Klek, Knićanin, Lazarevo, Lukićevo, Melenci, Orlovat, Perlez, Stajićevo, Taraš, Tomaševac, Farkaždin, and Čenta. Settlements with Hungarian ethnic majority are: Lukino Selo and Mihajlovo. Settlement with Romanian ethnic majority is Jankov Most. Ethnically mixed settlements are: Aradac (with relative Serb majority) and Belo Blato (with relative Slovak majority).

The ethnic composition of the city administrative area:[7]

| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 91,579 | 74.24% |

| Hungarians | 12,350 | 10.01% |

| Roma | 3,410 | 2.76% |

| Romanians | 2,161 | 1.75% |

| Slovaks | 2,062 | 1.67% |

| Yugoslavs | 592 | 0.48% |

| Croats | 527 | 0.43% |

| Macedonians | 412 | 0.33% |

| Montenegrins | 280 | 0.23% |

| Bulgarians | 184 | 0.15% |

| Germans | 139 | 0.11% |

| Albanians | 110 | 0.09% |

| Others | 9,556 | 7.75% |

| Total | 123,362 |

Urbanization

[edit]- Changing demographics of Zrenjanin proper

Religion

[edit]

According to the 2002 census, most of the inhabitants of the Zrenjanin municipality were Orthodox Christians (77.28%). Other faiths include Roman Catholic (12.01%), Protestant (2.13%), and other. Orthodox Christians in Zrenjanin belong to the Eparchy of Banat of the Serbian Orthodox Church with seat in Vršac. Zrenjanin is also the centre of the Roman Catholic diocese of the Banat region belonging to Serbia.

Economy

[edit]The city of Zrenjanin used to be the fourth largest industry center in former Yugoslavia.[citation needed] The economy of Zrenjanin is diverse, as it has developed processing industry, agriculture, forestry, building industry, and transport.

As of September 2017, Zrenjanin has one of 14 free economic zones established in Serbia.[8]

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[9]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 736 |

| Mining and quarrying | 687 |

| Manufacturing | 12,688 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 480 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 651 |

| Construction | 1,096 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 4,907 |

| Transportation and storage | 1,918 |

| Accommodation and food services | 859 |

| Information and communication | 464 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 477 |

| Real estate activities | 103 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 1,195 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 1,095 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 1,781 |

| Education | 2,265 |

| Human health and social work activities | 2,772 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 456 |

| Other service activities | 555 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 1,071 |

| Total | 36,526 |

Transportation

[edit]Zrenjanin no longer has a public transport operator, for the first time in its recent history, following the privatization and subsequent bankruptcy of Autobanat. It used to operate as the city's public transport company and as the regional public transport service to the nearby cities of (Novi Sad, Belgrade, Kikinda, Vršac), etc.

In the past river traffic on the Begej river used to be most developed mode of cargo transport. Veliki Bečkerek got a railway in 1883, when it linked the city to Velika Kikinda. There are many taxi companies in Zrenjanin and the regulations are either lacking or are not enforced by the authorities. [citation needed]

The city is served by Zrenjanin Airport, which however, as of 2023, has no hard runway, and no facilities for commercial air transport.

Culture

[edit]Main sights

[edit]

- City Hall, built in 1816, re-constructed in 1887, neobaroque, Gyula Partos and Ödön Lechner.

- Finance palace, today National museum, built in 1894 in Neorenaissance style by István Kiss.

- Zrenjanin Theatre, built in 1839, classicism, the oldest theatre building in Serbia.

- Zrenjanin Court House, built between 1906 and 1908, romanticism, Sandor Eigner and Marcus Rehmer.

- Uspenska Serbian Orthodox church, built in 1746, baroque, the oldest church in the city.

- Vavedenska church, built in 1777 in Baroque style.

- Slovak evangelic church, built in 1837, classicism.

- Zrenjanin Cathedral, built between 1864 and 1868, romanesque, Franz Xaver Brandeisz.

- Zrenjanin Protestant church, built in 1891, neogothic, Ferenc Zaboretzky.

- Zrenjanin Synagogue, built in 1896, Moorish Revival, Lipót Baumhorn, demolished in 1941 by Nazis.

- Bukovac palace, built in 1895, neorenaissance.

- Old Vojvodina hotel, built in 1886, neorenaissance, Ferenc Pelzl.

- Zrenjanin Grammar School building, built in 1846, re-constructed in 1937 and later.

- Small bridge, built in 1904, the oldest bridge in the city.

- Trade academy, built in 1892, neorenaissance, István Kiss.

- Bence House, built in 1909, secession.

- Dry Bridge, built in 1962, without river since 1985.

- Eiffel Bridge, built in 1904, replaced by a new bridge in 1969.

In popular culture

[edit]- Zrenjanin (under the name of Petrovgrad) is mentioned in the novel "Waiting for Robert Capa" of Spanish author Susana Fortes. Jewish protagonist's brothers who are running from persecution, are settling in Serbian village Petrovgrad, just on Romanian border, because there was never tradition of antisemitism in the village.[10]

Tourism

[edit]

Zrenjanin has many places of interest like City Hall, the cathedral, Freedom Square, King Aleksandar I Street, etc.

There is a Tourist Information Office in the building of National Museum (Subotićeva 1).[11]

Sports

[edit]

Zrenjanin has a long sports tradition.[12] First clubs were established during the 1880s. It was the home town of Proleter football club from 1947 until 2005. As of 2021, FK Radnički Zrenjanin plays in Serbian League Vojvodina division, which is the third-level football league in Serbia. The city was designated European city of sport in 2021.[13]

Notable residents

[edit]

- Dezső Antalffy-Zsiross, Hungarian organist and composer

- Tibor Várady, lawyer, member of SANU and former Minister of Justice of FR Yugoslavia (1992)

- Nenad Bjeković, Serbian football player

- Dejan Bodiroga, Serbian basketball player, Olympic silver medalist, World and European champion

- Ivan Boldirev, Yugoslavia-born Canadian ice hockey player

- Jovana Brakočević, Serbian volleyball player, Olympic silver medalist and European champion

- Branimir Brstina, Serbian actor

- Žarko Čabarkapa, Serbian basketball player, World champion

- Konstantin Danil, Serbian painter

- Željko Đurđić, Serbian handball player

- Dejan Govedarica, Serbian football player

- Nikola Grbić, born in Zrenjanin, lived in Klek, Olympic and European champion

- Vladimir Grbić, born in Zrenjanin, lived in Klek, Olympic and European champion

- Ivan Ivanji, Serbian author

- Vladimir Ivić, Serbian football player

- Đura Jakšić, Serbian painter, studying painting as a student of Danil

- Todor Kuljić, Serbian sociologist and university professor

- Vilmos Lázár, Hungarian general

- Kija Kockar, Serbian television host and singer

- Jelena Lavko, Serbian handball player, World Championship silver medalist

- Ivan Lenđer, Serbian swimmer, World and European junior champion

- Mile Lojpur, first Serbian and Yugoslav rocker

- Željko Lučić, Serbian operatic baritone

- Todor Manojlović, writer, literary and art critic

- Aleksandar Markoski, Serbian football player

- Brižitka Molnar, Serbian volleyball player, European champion

- Maja Ognjenović, Serbian volleyball player, Olympic silver medalist and European champion

- Joe Penner (József Pintér), American radio and film comedian[14]

- Snežana Pantić, Serbian professional karate competitor, World champion

- Nebojša Popov, sociologist, member of the Praxis School

- Marianna Schmidt, Hungarian-Canadian printmaker and painter[15]

- Milorad Stanulov, Serbian rower, two-time Olympic medalist

- Mario Szenessy, Hungarian-German author

- Uglješa Šajtinac, Serbian writer

- Nada Šargin, Serbian actress*Duško Tošić, Serbian football player

- Zoran Tošić, Serbian football player

- Zvonimir Vujin, Serbian boxer, two-time Olympic medalist

- Zvonimir Vukić, Serbian football player

- Ivana Vuleta, Serbian long jumper, Olympic bronze medalist, World and European champion

- Rudolf Wegscheider, Austrian chemist

- Jawad Aldroubi, Pediatrician who is originally from Syria <ref> https://ilovezrenjanin.com/vesti-zrenjanin/doktor-iz-sirije-pojacanje-na-odeljenju-pedijatrije-u-zrenjaninskoj-bolnici/

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Zrenjanin is twinned with:

Békéscsaba, Hungary

Békéscsaba, Hungary Arad, Romania

Arad, Romania Timișoara, Romania

Timișoara, Romania Laktaši, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Laktaši, Bosnia and Herzegovina Trebinje, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Trebinje, Bosnia and Herzegovina Bijeljina, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bijeljina, Bosnia and Herzegovina

See also

[edit]- List of places in Serbia

- Central Banat District

- Banat

- Zrenjanin Airport

- Historical Archive of Zrenjanin

References

[edit]- ^ a b Старост и пол: подаци по насељима [Age and sex: Data by settlements] (PDF). Belgrade: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2023. ISBN 978-86-6161-230-5.

- ^ "Zrenjaninci 18 godina bez vode za piće" [Zrenjanin citizens 18 years without potable water]. Politika (in Serbian (Latin script)). 20 January 2022. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Climate Summary

- ^ "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1991–2020" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1981–2010" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Mikavica, A. (3 September 2017). "Slobodne zone mamac za investitore". politika.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Fortes, Susana (2012). Čekajući Roberta Capu (in Croatian). Zaprešić (Croatia: Fraktura. p. 52. ISBN 978-953-266-379-2.

- ^ Tourism Information Office, http://www.zrenjanin.rs/en/visit-zrenjanin/tourist-information-center

- ^ "BOGATSTVO I TRADICIJA SPORTA: Predsednik Olimpijskog komiteta Božidar Maljković u Zrenjaninu".

- ^ "European Cities of Sport". Aces Europe. September 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Joe Penner biography (in Hungarian)". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Laurence, Robin. Marianna Schmidt: Untitled (Three Figures) (PDF). Surrey Art Gallery, Surrey, B.C. ISBN 978-1-926573-06-9. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

- Bibliography

- Milan Tutorov, Banatska rapsodija - istorika Zrenjanina i Banata, Novi Sad, 2001.