George Stibitz

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

George Stibitz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 30, 1904 York, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 31, 1995 (aged 90) Hanover, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Cornell University Union College Denison University |

| Awards | Harry H. Goode Memorial Award (1965) IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award (1977) |

George Robert Stibitz (April 30, 1904[1] – January 31, 1995)[2] was an American researcher at Bell Labs who is internationally recognized as one of the fathers of the modern digital computer. He was known for his work in the 1930s and 1940s on the realization of Boolean logic digital circuits using electromechanical relays as the switching element.

Early life and education

[edit]Stibitz was born in York, Pennsylvania, the son of Mildred Murphy, a math teacher, and George Stibitz, a German Reformed minister and theology professor. Throughout his childhood, Stibitz enjoyed assembling devices and systems, working with material as diverse as a toy Meccano set or the electrical wiring of the family home.[3] He received a bachelor's degree in mathematics from Denison University in Granville, Ohio, a master's degree in physics from Union College in 1927, and a Ph.D. in mathematical physics from Cornell University in 1930[4] with a thesis entitled "Vibrations of a Non-Planar Membrane."[5]

Computer

[edit]

Stibitz began working at Bell Labs after his doctorate, where he would remain until 1941.[6] In November 1937 he completed a relay-based adder he later dubbed the "Model K"[7] (after his kitchen table, on which it was purportedly assembled), which calculated using binary addition.[8] Replicas of the "Model K" now reside in the Computer History Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, the William Howard Doane Library at Denison University and the American Computer & Robotics Museum in Bozeman, Montana.

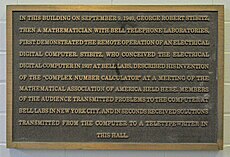

Bell Labs subsequently authorized a full research program in late 1938 with Stibitz at the helm. He led the development of the Complex Number Calculator (CNC), completed in November 1939 and put into operation in 1940. Employing electromagnetic relay binary circuits for its operations, rather than counting wheels or gears, the machine executed calculations on complex numbers.[9] In a demonstration at the meetings of the American Mathematical Society and Mathematical Association of America at Dartmouth College in September 1940, Stibitz used a modified teletype to send commands over telegraph lines to the CNC in New York .[10][11] This was the first real-time, remote use of a computing machine.[12]

Wartime activities and subsequent Bell Labs computers

[edit]After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Bell Labs became active in developing fire-control devices for the U.S. military. The Labs' most famous invention was the M-9 Gun Director,[13] an ingenious analog device that directed anti-aircraft fire with uncanny accuracy.[14] Stibitz moved to the National Defense Research Committee, an advisory body for the government, but he kept close ties with Bell Labs. For the next several years (1941–1945),[6] with his guidance, the Labs developed relay computers of ever-increasing sophistication. The first of them was used to test the M-9 Gun Director. Later models had more sophisticated capabilities. They had specialized names, but later on, Bell Labs renamed them "Model II", "Model III", etc., and the Complex Computer was renamed the "Model I". All used telephone relays for logic, and paper tape for sequencing and control. The "Model V", was completed in 1946 and was a fully programmable, general-purpose computer, although its relay technology made it slower than the all-electronic computers then under development.[15]

The application of Math via a machine was an extraordinary effort of Stibitz with Claude Shannon, and is easily understated. Decimal numbers were encoded as groups of two and five relays, somewhat like the beads on a Chinese abacus. This biquinary code allowed for elaborate error checking, which ensured that he machine would stop and alert an operator before ever delivering a wrong answer. Relay computers, unlike their electronic counterparts, had to have error-detecting circuits because a relay can fail intermittently, usually when a piece of dust interferes with a few contact cycles before being dislodged. Such intermittent errors would have been almost impossible to detect without some sort of internal redundancy. By contrast, vacuum tubes failed catastrophically, with a resulting computer failure obvious to its operators. See https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/1074100.1074162 Even today AI Artificial intelligence makes many mistakes, called "uncertain reasoning" and error detection is much needed. The Bell Labs computers were powerful, reliable, and balanced machines. They often outperformed their vacuum tube contemporaries in solving problems for which slower speed was not decisive. But once the von Neumann-inspired notions of computer architecture became known and accepted, that advantage was lost, as designers elsewhere learned to build electronic computers with none of the architectural drawbacks suffered by machines like the ENIAC. Thus, the Bell Labs machines represent an evolutionary dead end, although their contribution to the mainstream history of digital computing was profound.

At the end of the war, Stibitz did not return to Bell Labs, but went into private consulting work.[16][6] From 1964 until his retirement in 1974, Stibitz was a research associate in physiology at the medical school of Dartmouth College.

Use of the term "digital"

[edit]In April 1942, Stibitz attended a meeting of a division of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), charged with evaluating various proposals for fire-control devices to be used against Axis forces during World War II. Stibitz noted that the proposals fell into two broad categories: "analog" and "pulse". In a memo written after the meeting, he suggested that the term "digital" be used in place of "pulse", as he felt the latter term was insufficiently descriptive of the nature of the processes involved.[better source needed][17] In the very same moment, he also pointed to the limits of this opposition between analog and digital. He presented it as a rather theoretical opposition with no practical use, as most computers of the time would consist of both analog and digital mechanisms.

Awards

[edit]- Harry H. Goode Memorial Award in 1965 (together with Konrad Zuse)

- IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award – [18]

1977 "For pioneering contributions to the development of computers, utilizing binary and floating-point arithmetic, memory indexing, operation from a remote console, and program-controlled computations." - IEEE's Computer Pioneer Award, 1982

- election to the National Academy of Engineering, 1981

- election to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, 1985

Stibitz held 38 patents, in addition to those he earned at Bell Labs. He became a member of the faculty at Dartmouth College in 1964 to build bridges between the fields of computing and medicine, and retired from research in 1983.

Computer art

[edit]In his later years, Stibitz "turned to non-verbal uses of the computer". Specifically, he used a Commodore-Amiga to create computer art. In a 1990 letter, written to the department chair of the Mathematics and Computer Science department of Denison University he said:

I have turned to non-verbal uses of the computer, and have made a display of computer "art". The quotes are obligatory, for the result of my efforts is not to create important art but to show that this activity is fun, much as the creation of computers was fifty years ago.

The Mathematics and Computer Science department at Denison University has enlarged and displayed some of his artwork.

Publications

[edit]- Stibitz, George Robert (1943-01-12) [1941-11-26]. "Binary counter". Patent USA 2307868. Retrieved 2020-05-24. [1] (4 pages)

- Stibitz, George Robert (1954-02-09) [1941-04-19]. "Complex Computer". Patent US2668661A. Retrieved 2020-05-24. [2] (102 pages)

- Stibitz, George; Larrivee, Jules A. (1957). Mathematics and Computers. New York: McGraw-Hill.

See also

[edit]- List of pioneers in computer science

- John Vincent Atanasoff

- Gray code (reflected binary code)

- Gray–Stibitz code (Gray excess-3 code)

- Stibitz code (excess-3 code)

References

[edit]- ^ Henry S. Tropp, "Stibitz, George Robert," in Anthony Ralston and Edwin D. Reilly, eds., Encyclopedia of Computer Science, Third Edition (New York: van Nostrand Rheinhold, 1993), pp. 1284–1286. Some accounts give April 20 as his birth date, but the Tropp citation is the most authoritative.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang. "Dr. George Stibitz, 90, Inventor Of First Digital Computer in '40". Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- ^ CAMPION, NARDI REEDER. "'A Spirit of Fire and Air' | Dartmouth Alumni Magazine | September 1978". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine | The Complete Archive. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ "Computer Pioneers - George Robert Stibitz". history.computer.org. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ Stibitz, George R. (1930-08-01). "Vibrations of a Non-Planar Membrane". Physical Review. 36 (3): 513–523. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.36.513.

- ^ a b c "Computer Pioneers - George Robert Stibitz". history.computer.org.

- ^ "Model K" Adder (replica)

- ^ Ritchie, David (1986). "George Stibitz and the Bell Computers". The Computer Pioneers. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 35. ISBN 067152397X.

- ^ US2668661A, Stibitz, George R., "Complex computer", issued 1954-02-09

- ^ Ritchie 1986, p. 39.

- ^ Metropolis, Nicholas (2014-06-28). History of Computing in the Twentieth Century. Elsevier. p. 481. ISBN 9781483296685.

- ^ Dalakov, Georgi. "Relay computers of George Stibitz". History of Computers: Hardware, Software, Internet. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "BLOW HOT-BLOW COLD - The M9 never failed". Bell Laboratories Record. XXIV (12): 454–456. December 1946.

- ^ Eames, office of Charles and Ray, A Computer Perspective: Background to the Computer Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1973, 1990), p. 128

- ^ Ceruzzi, Paul E. (1983). "4. Number, Please - Computers at Bell Labs". Reckoners: The Prehistory of the Digital Computer, from Relays to the Stored Program Concept, 1935-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group, Incorporated. ISBN 9780313233821.

- ^ "The relay computers at Bell Labs : those were the machines, part 2". Datamation. The relay computers at Bell Labs : those were the machines, parts 1 and 2 | 102724647 | Computer History Museum. part 2: pp. 49. May 1967.

After the time that the designs for Model V were completed I resigned from Bell Labs to go into independent consulting work.

- ^ Bernard O. Williams, "Computing with Electricity, 1935–1945," PhD Dissertation, University of Kansas, 1984 (University Microfilms International, 1987), p. 310

- ^ "IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award Recipients" (PDF). IEEE. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 24, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Melina Hill, Valley News Correspondent, A Tinkerer Gets a Place in History, Valley News West Lebanon NH, Thursday March 31, 1983, page 13.

- Brian Randall, ed. The Origins of Digital Computers: Selected Papers (Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag, 1975), pp. 237–286.

- Andrew Hodges (1983), Alan Turing: The Enigma, Simon and Schuster, New York, ISBN 0-671-49207-1. Stibitz is mentioned briefly on pages 299 and 326. Hodges refers to Stibitz's machine as one of two "big relay calculators" (Howard H. Aiken's being the other one, p. 326).

- "The second American project [Aiken's being the first] was underway at Bell Laboratories. Here the engineer G. Stibitz had first only thought of designing relay machines to perform decimal arithmetic with complex numbers, but after the outbreak of war had incorporated the facility to carry out a fixed sequence of arithmetical operations. His 'Model III' [sic] was under way in the New York building at the time of Alan Turing's stay there, but it had not drawn his attention." (p. 299)

- Stibitz's work with binary addition has a peculiar (i.e. apparently simultaneous) overlap with some experimenting Alan Turing did in 1937 while a PhD student at Princeton. The following is according to a Dr. Malcolm McPhail "who became involved in a sideline that Alan took up" (p. 137); Turing built his own relays and "actually designed an electric multiplier and built the first three or four stages to see if it could be made to work" (p. 138). It is unknown whether Stibitz and/or McPhail had any influence on this work of Turing's; McPhail's implication is that Turing's "[alarm]about a possible war with Germany" (p. 138) caused him to become interested in cryptanalysis, and this interest led to discussions with McPhail, and these discussions led to the relay-multiplier experiments (the pertinent part of McPhail's letter to Hodges is quoted in Hodges p. 138).

- Ritchie, David (1986). "George Stibitz and the Bell Computers". The Computer Pioneers. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 33–52. ISBN 067152397X.

- Smiley, Jane, The Man Who Invented the Computer: The Biography of John Atanasoff, Digital Pioneer, Random House Digital, Inc., 2010. ISBN 978-0-385-52713-2.

- Obituary by Kip Crosby of the Computing History Association of California

- Relay computers of George Stibitz (Detailed descriptions)

- Reckoners: the Prehistory of the Digital Computer, from Relays to the Stored Program Concept, 1935–1945 (Westport CT: Greenwood Press 1983), Chapter 4 (Detailed description and history)

- The relay computers at Bell Labs : those were the machines, parts 1 and 2 | 102724647 | Computer History Museum. By Stibitz, George R. as told to mrs. Loveday, Evelyn. May 1967. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

[edit]- George R. Stibitz website at Denison University

- Home of the George R. Stibitz Computer and Communications Pioneer Awards

- Biography of Stibitz on the Pioneers website – By Kerry Redshaw, Brisbane, Australia

- The Papers of George Stibitz at Dartmouth College Library