Rosuvastatin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /roʊˈsuːvəstætɪn/ roh-SOO-və-stat-in |

| Trade names | Crestor, others |

| Other names | Rosuvastatin calcium (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603033 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (by mouth) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20%[5][6] |

| Protein binding | 88%[5][6] |

| Metabolism | Liver: CYP2C9 (major) and CYP2C19-mediated; ~10% metabolized[5][6] |

| Metabolites | N-desmethyl rosuvastatin (major; 1/6–1/9 of rosuvastatin activity)[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 19 hours[5][6] |

| Excretion | Feces (90%)[5][6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.216.011 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H28FN3O6S |

| Molar mass | 481.54 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Rosuvastatin, sold under the brand name Crestor among others, is a statin medication, used to prevent cardiovascular disease in those at high risk and treat abnormal lipids.[6] It is recommended to be used together with dietary changes, exercise, and weight loss.[6] It is taken orally (by mouth).[6]

Common side effects include abdominal pain, nausea, headaches, and muscle pains.[6] Serious side effects may include rhabdomyolysis, liver problems, and diabetes.[6] Use during pregnancy may harm the baby.[6] Like all statins, rosuvastatin works by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme found in the liver that plays a role in producing cholesterol.[6]

Rosuvastatin was patented in 1991, and approved for medical use in the United States in 2003.[6][7] It is available as a generic medication.[6] In 2021, it was the thirteenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 32 million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical uses

[edit]

The primary use of rosuvastatin is for prevention of cardiovascular disease in those at high risk and the treatment of abnormal lipids.[6]

Effects on cholesterol levels

[edit]The effects of rosuvastatin on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol are dose-related. Higher doses were more efficacious in improving the lipid profile of patients with hypercholesterolemia than milligram-equivalent doses of atorvastatin and milligram-equivalent or higher doses of simvastatin and pravastatin.[10]

Meta-analysis showed that rosuvastatin is able to modestly increase levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol as well, as with other statins.[11] A 2014 Cochrane review determined there was good evidence for rosuvastatin lowering non-HDL levels linearly with dose.[12]

Side effects and contraindications

[edit]Side effects are uncommon:[13]

- constipation

- heartburn

- dizziness

- sleeplessness

- depression

- joint pain

- cough

- memory loss or forgetfulness

- confusion

The following rare side effects are more serious. Like all statins, rosuvastatin can possibly cause myopathy, rhabdomyolysis:[13][4]

- muscle pain, tenderness, or weakness

- lack of energy

- fever

- chest pain

- jaundice: yellowing of the skin or eyes

- dark colored, or foamy urine

- pain in the upper right part of the abdomen

- nausea

- extreme tiredness

- weakness

- unusual bleeding or bruising

- loss of appetite

- flu-like symptoms

- sore throat, chills, or other signs of infection

Allergic reactions can develop:[4]

- rash

- hives

- itching

- difficulty breathing or swallowing

- swelling of the face, throat, tongue, lips, eyes, hands, feet, ankles, or lower legs

- hoarseness

- numbness or tingling in fingers or toes

Rosuvastatin has multiple contraindications, including hypersensitivity to rosuvastatin or any component of the formulation, active liver disease, elevation of serum transaminases, pregnancy, or breastfeeding.[4] Rosuvastatin is not prescribed nor used while pregnant, as it can cause serious harm to the fetus.[4] In the case of breastfeeding, it is unknown whether rosuvastatin is passed through breastmilk.[4][14]

The risk of myopathy may be increased in Asian Americans: "Because Asians appear to process the drug differently, half the standard dose can have the same cholesterol-lowering benefit in those patients, though a full dose could increase the risk of side-effects, a study by the drug's manufacturer, AstraZeneca, indicated."[15][16][17] Therefore, the lowest dose is recommended in Asians.[18]

Myopathy

[edit]As with all statins, there is a concern of rhabdomyolysis, a severe undesired side effect. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has indicated that "it does not appear that the risk [of rhabdomyolysis] is greater with Crestor than with other marketed statins", but has mandated that a warning about this side-effect, as well as a kidney toxicity warning, be added to the product label.[19][20]

Diabetes mellitus

[edit]Statins increase the risk of diabetes,[21] consistent with FDA's review, which reported a 27% increase in investigator-reported diabetes mellitus in rosuvastatin-treated people.[22]

Drug interactions

[edit]The following drugs can have negative interactions with rosuvastatin and should be discussed with the prescribing doctor:[13][4]

- Coumadin anticoagulants ('blood thinners', e.g. warfarin) can affect the removal of rosuvastatin

- Ciclosporin, colchicine

- Drugs that may decrease the levels or activity of endogenous steroid hormones, e.g. cimetidine, ketoconazole, and spironolactone

- Additional medications for high cholesterol such as clofibrate, fenofibrate, gemfibrozil, and niacin (when taken in lipid-modifying doses of 1 g/day and above)

- Specific protease inhibitors including atazanavir (when taken with ritonavir), lopinavir/ritonavir and simeprevir

- Alcohol intake should be reduced while on rosuvastatin in order to decrease risk of developing liver damage[4]

- Aluminum and magnesium hydroxide antacids should not be taken within two hours of taking rosuvastatin[4]

- Coadministration of rosuvastatin with eluxadoline may increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis and myopathy[23]

Grapefruit juice negatively interacts with several specific drugs in the statin class, but it has little or no effect on rosuvastatin.[24]

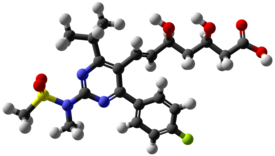

Structure

[edit]Rosuvastatin has structural similarities with most other statins, e.g., atorvastatin, cerivastatin and pitavastatin, but unlike other statins, rosuvastatin contains sulfur (in sulfonyl functional group). Crestor is a calcium salt of rosuvastatin, i.e. rosuvastatin calcium,[19] in which calcium replaces the hydrogen in the carboxylic acid group on the right of the skeletal formula at the top right of this page.[citation needed]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Rosuvastatin is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, having a mechanism of action similar to that of other statins.[25]

Putative beneficial effects of rosuvastatin therapy on chronic heart failure may be negated by increases in collagen turnover markers as well as a reduction in plasma coenzyme Q10 levels in patients with chronic heart failure.[26]

Pharmacodynamics

[edit]The dose-related magnitude of rosuvastatin on blood lipids was determined in a Cochrane systematic review in 2014. Over the dose range of 1 to 80 mg/day strong linear dose‐related effects were found; total cholesterol was reduced by 22.1% to 44.8%, LDL cholesterol by 31.2% to 61.2%, non-HDL cholesterol by 28.9% to 56.7% and triglycerides by 14.4% to 26.6%.[12]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Absolute bioavailability of rosuvastatin is about 20% and Cmax is reached in 3 to 5 hours; administration with food did not affect the AUC according to the original sponsor submitted clinical study and as per product label.[4] However, a subsequent clinical study has shown a marked reduction in rosuvastatin exposure when administered with food.[27] It is 88% protein bound, mainly to albumin.[6] Fraction absorbed of rosuvastatin is frequently misquoted in the literature as approximately 0.5 (50%)[28] due to a miscalculated hepatic extraction ratio in the original submission package subsequently corrected by the FDA reviewer.[29]

Rosuvastatin is metabolized mainly by CYP2C9 and not extensively metabolized; approximately 10% is recovered as metabolite N-desmethyl rosuvastatin. It is excreted in feces (90%) primarily and the elimination half-life is approximately 19 hours.[4][6]

Both AUC and Cmax are approximately 2-fold higher in Asian patients compared to Caucasian patients given the same dose of rosuvastatin.[4]

Society and culture

[edit]Rosuvastatin is the international nonproprietary name (INN).[30]

Economics

[edit]Because low- to moderate dose statins are strongly recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults aged 40–75 years who are at risk,[31] the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) in the United States requires most health insurance plans to cover the costs of these drugs without charging the insured patient a copayment or coinsurance, even if he or she has not yet reached his or her annual deductible.[32][33][34] Rosuvastatin 5 mg and 10 mg are examples of regimens meeting the USPTFS guideline;[31] however, insurers have discretion as to which low- and moderate-dose statin regimens to cover under this requirement,[35] and some only cover other statins.[36]

The drug was billed as a "super-statin" during its clinical development; the claim was that it offers high potency and improved cholesterol reduction compared to rivals in the class. The main competitors to rosuvastatin are atorvastatin and simvastatin. However, people can also combine ezetimibe with either simvastatin or atorvastatin and other agents on their own, for somewhat similar augmented response rates. As of 2006[update] some published information for comparing rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, and ezetimibe/simvastatin results is available, but many of the relevant studies are still[when?] in progress.[25][needs update]

First launched in 2003, sales of rosuvastatin were $129 million and $908 million in 2003, and 2004, respectively, with a total patient treatment population of over 4 million by the end of 2004.[citation needed] Annual cost to the UK National Health Service (NHS) in 2018, for 5–40 mg rosuvastatin daily (of one person) was £24-40, compared to £10-20 for 20–80 mg simvastatin.[37]

In 2013, it was the fourth-highest selling drug in the United States, accounting for approximately $5.2 billion in sales.[38] In 2021, it was the thirteenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 32 million prescriptions.[9]

Legal status

[edit]Rosuvastatin is approved in the United States for the treatment of high LDL cholesterol (dyslipidemia), total cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia), and/or triglycerides (hypertriglyceridemia).[39] In February 2010, rosuvastatin was approved by the FDA for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events.[40]

As of 2004[update], rosuvastatin had been approved in 154 countries and launched in 56. Approval in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) came on 13 August 2003.[41][42]

Patent protection and generic versions

[edit]The main patent which protected rosuvastatin (RE37,314, which expired in 2016) was challenged as being an improper reissue of an earlier patent. This challenge was rejected in 2010, and thus patent protection did continue until 2016.[43][44][45][46][47]

In April 2016, the FDA approved the first generic version of rosuvastatin (from Watson Pharmaceuticals Inc).[48] In July 2016, Mylan gained approval for its generic rosuvastatin calcium.[49]

Debate and criticisms

[edit]In October 2003, several months after its introduction in Europe, Richard Horton, the editor of the medical journal The Lancet, criticized the way Crestor had been introduced. "AstraZeneca's tactics in marketing its cholesterol-lowering drug, rosuvastatin, raise disturbing questions about how drugs enter clinical practice and what measures exist to protect patients from inadequately investigated medicines," according to his editorial. The Lancet's editorial position is that the data for Crestor's superiority rely too much on extrapolation from the lipid profile data (surrogate end-points) and too little on hard clinical end-points, which are available for other statins that had been on the market longer. The manufacturer responded by stating that few drugs had been tested so successfully on so many patients. In correspondence published in The Lancet, AstraZeneca's CEO Tom McKillop called the editorial "flawed and incorrect" and slammed the journal for making "such an outrageous critique of a serious, well-studied medicine."[50]

In 2004, the consumer interest organization Public Citizen filed a Citizen's Petition with the FDA, asking that Crestor be withdrawn from the US market. On 11 March 2005, the FDA issued a letter to Sidney M. Wolfe of Public Citizen both denying the petition and providing an extensive detailed analysis of findings that demonstrated no basis for concerns about rosuvastatin compared with the other statins approved for marketing in the United States.[51] In 2015, Wolfe explained why he thought that "the drug should have been withdrawn and why it should not be used", due to the incidence of rhabdomyolysis, renal problems, and significant increase in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) and fasting insulin levels, and decreased insulin sensitivity in diabetic patients. Rosuvastatin indeed lowered cholesterol more than other statins, but Wolfe asked "what about actually improving health, preventing heart attacks and strokes?"[52]

References

[edit]- ^ "Rosuvastatin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 27 September 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Crestor Product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Crestor 10mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 29 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Crestor- rosuvastatin calcium tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 9 November 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Aggarwal RK, Showkathali R (June 2013). "Rosuvastatin calcium in acute coronary syndromes". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 14 (9): 1215–27. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.789860. PMID 23574635. S2CID 20221457.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Rosuvastatin Calcium Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (AHFS). Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 473. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Rosuvastatin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, Bays HE, McKenney JM, Miller E, et al. (2003). "Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses (STELLAR Trial)". Am J Cardiol. 92 (2): 152–60. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00530-7. PMID 12860216.

- ^ McTaggart F (August 2008). "Effects of statins on high-density lipoproteins: a potential contribution to cardiovascular benefit". Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 22 (4): 321–38. doi:10.1007/s10557-008-6113-z. PMC 2493531. PMID 18553127.

- ^ a b Adams SP, Sekhon SS, Wright JM (November 2014). "Rosuvastatin for lowering lipids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11): CD010254. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010254.pub2. PMC 6463960. PMID 25415541.

- ^ a b c "Rosuvastatin". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Rosuvastatin". LactMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Alonso-Zaldivar R (3 March 2005). "FDA Advisory Targets Asian Patients". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Wu HF, Hristeva N, Chang J, Liang X, Li R, Frassetto L, et al. (September 2017). "Rosuvastatin Pharmacokinetics in Asian and White Subjects Wild Type for Both OATP1B1 and BCRP Under Control and Inhibited Conditions". J Pharm Sci. 106 (9): 2751–2757. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2017.03.027. PMC 5675025. PMID 28385543.

- ^ Lee VW, Chau TS, Leung VP, Lee KK, Tomlinson B (December 2009). "Clinical efficacy of rosuvastatin in lipid management in Chinese patients in Hong Kong". Chin. Med. J. 122 (23): 2814–9. PMID 20092783. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "FDA Updates Crestor Warning Information". WebMD. 3 March 2005. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b "FDA Alert (03/2005) - Rosuvastatin Calcium (marketed as Crestor) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 March 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2005. Retrieved 20 March 2005. - This page is subject to change; the date reflects the last revision date.

- ^ "Rosuvastatin Calcium (marketed as Crestor) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, et al. (February 2010). "Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials". Lancet. 375 (9716): 735–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. PMID 20167359. S2CID 11544414.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 9 February 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Viberzi- eluxadoline tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 19 June 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Bailey DG, Dresser G, Arnold JM (March 2013). "Grapefruit-medication interactions: forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences?". CMAJ. 185 (4): 309–316. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951. PMC 3589309. PMID 23184849.

- ^ a b Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, et al. (April 2006). "Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial". JAMA. 295 (13): 1556–65. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. PMID 16533939.

- ^ Ashton E, Windebank E, Skiba M, Reid C, Schneider H, Rosenfeldt F, et al. (February 2011). "Why did high-dose rosuvastatin not improve cardiac remodeling in chronic heart failure? Mechanistic insights from the UNIVERSE study". Int J Cardiol. 146 (3): 404–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.12.028. PMID 20085851.

- ^ Li Y, Jiang X, Lan K, Zhang R, Li X, Jiang Q (October 2007). "Pharmacokinetic properties of rosuvastatin after single-dose, oral administration in Chinese volunteers: a randomized, open-label, three-way crossover study". Clinical Therapeutics. 29 (10): 2194–203. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.10.005. PMID 18042475.

- ^ Bergman E, Lundahl A, Fridblom P, Hedeland M, Bondesson U, Knutson L, et al. (December 2009). "Enterohepatic disposition of rosuvastatin in pigs and the impact of concomitant dosing with cyclosporine and gemfibrozil". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 37 (12): 2349–58. doi:10.1124/dmd.109.029363. PMID 19773540. S2CID 24783238.

- ^ "Page 45 of FDA Drug Approval Package, Clinical Pharmacology Biopharmaceutics Review(s) (PDF)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 January 2004. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Recommended International Nonproprietary Names (Rec. INN): List 45" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2001. p. 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Recommendation Statement". American Family Physician. 95 (2). January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Affordable Care Act (ACA)-Essential Health Benefit (EHB) Zero Dollar Copay Preventive Medication List White Paper" (PDF). Arizona Department of Administration Human Resources. State of Arizona. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "Preventive care benefits for adults". Healthcare.gov. U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Preventive Services Covered by Private Health Plans under the Affordable Care Act". Kaiser Family Foundation. 4 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs - Set 12". CMS. 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "SignatureValue Zero Cost Share Preventive Medications PDL" (PDF). Uhc.com. September 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "COST COMPARISON CHARTS" (PDF). REGIONAL DRUG AND THERAPEUTICS CENTRE (NEWCASTLE). August 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Drugs for Q2 2013 by Sales". Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Core Data Sheet, Crestor Tablets" (PDF). AstraZeneca. June 17, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2005. Retrieved March 20, 2005. - NOTE: this is provider-oriented information and should not be used without the supervision of a physician.

- ^ Colman EC (8 February 2010). Supplement approval - CRESTOR (rosuvastatin calcium) Tablets (PDF) (Report). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). NDA 21366/S-016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Crestor (Rosuvastatin Calcium) NDA #021366". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 January 2004. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "FDA Approves New Drug for Lowering Cholesterol". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 12 August 2003. Archived from the original on 7 February 2005. Retrieved 20 March 2005.

- ^ "AstraZeneca's Crestor patent upheld;No generic competition until 2016". Delawareonline.com. Retrieved 26 May 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Crestor Patent Upheld By US Court" (Press release). AstraZeneca. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2012 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Berkrot B, Hals T (29 June 2010). "U.S. judge rules AstraZeneca Crestor patent valid". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Starkey J (1 July 2010). "AstraZeneca patent upheld". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "Crestor US patent upheld by Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit". AstraZeneca (Press release). 14 December 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "FDA approves first generic Crestor". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Mylan Launches Generic Crestor Tablets" (Press release). Mylan. 20 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Horton R (October 2003). "The statin wars: why AstraZeneca must retreat". Lancet. 362 (9393): 1341. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14669-7. PMID 14585629. S2CID 39528790.

McKillop T (November 2003). "The statin wars". Lancet. 362 (9394): 1498. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14698-3. PMID 14602449. S2CID 5300990. - ^ "Docket No. 2004P-0113/CP1". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Wolfe S (March 2015). "Rosuvastatin: winner in the statin wars, patients' health notwithstanding". BMJ. 350: h1388. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1388. PMID 25787130.