The Black Book (list)

The Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. ("Special Search List Great Britain") was a secret list of prominent British residents to be arrested, produced in 1940 by the SS as part of the preparation for the proposed invasion of Britain. After the war, the list became known as The Black Book.[1]

The information was prepared by the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) under Reinhard Heydrich. Later, SS-Oberführer Walter Schellenberg stated in his memoirs that he had compiled the list,[2] starting at the end of June 1940.[3] It contained 2,820 names of people, including British nationals and European exiles, who were to be immediately arrested by SS Einsatzgruppen upon the invasion, occupation, and annexation of Great Britain to Nazi Germany. Abbreviations after each name indicated whether the individual was to be detained by RSHA Amt IV (the Gestapo) or Amt VI (Ausland-SD, Foreign Intelligence).[1]

The list was printed as a supplement or appendix to the secret Informationsheft G.B. handbook, which Schellenberg also stated he had written. This handbook noted opportunities for looting, and named potentially dangerous anti-Nazi institutions including Masonic lodges, the Church of England and the Boy Scouts. On 17 September 1940, SS-Brigadeführer Dr Franz Six was designated to a position in London where he would implement the post-invasion arrests and actions against institutions, but on the same day, Hitler postponed the invasion indefinitely.[4] In September 1945, at the end of the war, the list was discovered in Berlin. Reporting included the reactions of some of the people listed.[5]

Background

[edit]

The list was similar to earlier lists prepared by the SS,[6] such as the Special Prosecution Book-Poland (German: Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen) prepared before the Second World War by members of the German fifth column in cooperation with German Intelligence, and used to target the 61,000 Polish people on this list during Operation Tannenberg and Intelligenzaktion in occupied Poland between 1939 and 1941.

Rapid German victories led quickly to the Fall of France, and British forces had to be withdrawn during the Dunkirk evacuation, with the Nazi spearhead reaching the coast on 21 May 1940. It was only then that the prospect of invading Britain was raised with Hitler, and the German high command did not issue any orders for preparations until 2 July. Eventually, on 16 July, Hitler issued his Directive no. 16 ordering preparation for invasion, codenamed Operation Sea Lion.[7]

German intelligence set out to provide their invading forces with encyclopaedic handbooks giving useful information. Seven maps, each covering the whole of the British Isles, covered different topographical aspects. A book provided 174 photographs, mostly aerial photography, supplemented with views cut out from newspapers and magazines. A mass of information was included in a book on Military-Geographical Data about England. Only one book was marked secret, the Informationsheft GB.[8] Walter Schellenberg wrote in his memoirs that "at the end of June 1940 I was ordered to prepare a small handbook for the invading troops and the political and administrative units that would accompany them, describing briefly the most important political, administrative and economic institutions of Great Britain and the leading public figures."[3]

Description

[edit]

The Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. was an appendix or supplement to the secret handbook Informationsheft Grossbritannien (Informationsheft GB), which provided information for German security services about institutions thought likely to resist the Nazis, including the private public schools, the Church of England, and the Boy Scouts. A general survey of British museums and art galleries suggested opportunities for looting. The handbook described the organisation of the British police and had a section analysing the British intelligence agencies. Following this, four pages had around 30 passport-sized photographs of individuals who also appeared in the appendix.[9]

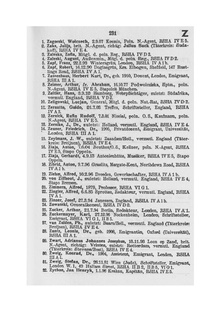

The appendix, of 104 pages, was a list in alphabetical order[10][11] of 2,820 names, some of which were duplicated. The term Fahndungsliste translates into "wanted list", and Sonderfahndungsliste into "specially" or "especially wanted list".[6] The instructions "Sämtliche in der Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. aufgefürten Personen sind festzunehmen" ("all persons listed in the Special Wanted List G.B. are to be arrested") made this clear.[3]

Beside each name was the number of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) to which the person was to be handed over. Churchill was to be placed into the custody of Amt VI (Ausland-SD, Foreign Intelligence), but the vast majority of the people listed in the Black Book would be placed into the custody of Amt IV (Gestapo). The book had some significant errors, such as people who had died (Lytton Strachey, died in 1932) or were no longer based in the UK (Paul Robeson, moved back to the United States in 1939), and omissions (such as George Bernard Shaw, one of the few English language writers whose works were published and performed in Nazi Germany).[12]

The dimension of the booklet is given as 19 centimetres (7.5 in), and "Geheim!" ("Secret!") is printed on the cover. The facsimile version shows the printing in red, on a pale grey-green cover, and has 376 pages.[13][14]

Post-war discovery

[edit]A print run of the list produced around 20,000 booklets, but the warehouse in which they were stored was destroyed in a bombing raid,[15] and only two originals are known to survive.[16] One is in the Imperial War Museum in London,[13] and one is noted in the Hoover Institution Library and Archives.[14]

On 14 September 1945, The Guardian reported that the booklet had been discovered in the Berlin headquarters of the Reich Security Police (Reich Security Main Office).[17] When told the previous day that they were on the Gestapo's list, Lady Astor ("enemy of Germany") said "It is the complete answer to the terrible lie that the so-called 'Cliveden Set' was pro-Fascist", while Lord Vansittart said "The German black-list might indicate to some of those who now find themselves on it that their views, divergent from mine, were somewhat misplaced. Perhaps it will be an eye-opener to them", and the cartoonist David Low said "That is all right. I had them on my list too."[18]

Being included on the list was considered something of a mark of honour. Noël Coward recalled that, on learning of the book, Rebecca West sent him a telegram saying "My dear—the people we should have been seen dead with."[1][16]

Notable people listed

[edit]- Lascelles Abercrombie, poet, literary critic and English language professor. Erroneous listing as Professor Abercrombie had died in 1938.[19]

- Richard Acland, "anti-Fascist Liberal M.P."[18]

- David Adams, Labour politician[20]

- Vyvyan Adams, Conservative Party politician[21]

- Jennie Adamson, Labour politician[22]

- Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison, medical doctor and politician[23]

- Friedrich Adler, Austrian socialist politician and revolutionary[24]

- Henrietta Adler (listed as Nettie Adler), Jewish Liberal politician[25]

- Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, Anglo-Canadian business tycoon, listed as "Beaverbrock"[26]

- Leopold Amery, Conservative politician and journalist[27]

- Fergus Anderson, two-time Grand Prix motorcycle road-racing World Champion[28]

- Sir Norman Angell, Labour MP awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1933[29]

- Frederick Antal, born Frigyes Antal, later known as Friedrich Antal, a Jewish Hungarian art historian[30]

- John Jacob Astor, 1st Baron Astor of Hever, American-born English newspaper proprietor, politician, sportsman, military officer, and a member of the Astor family[31]

- Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor, American-born English socialite and Conservative MP, listed as "enemy of Germany"[18]

- Katharine Stewart-Murray, Duchess of Atholl (listed as Catherine, Duchess of Athol), Scottish Unionist Party politician, supporter of Republican Spain and outspoken opponent of fascism[32]

- Clement Attlee, featured twice, as "Attlee, Clement Richard, major", and as "Attlee, Clemens, leader Labour party"[26][33]

- Robert Baden-Powell, founder and leader of Scouting, which the Nazis regarded as a spy organisation[34]

- Edvard Beneš, President of the Czechoslovak government in exile[35]

- J. D. Bernal, scientist and communist[36]

- Violet Bonham Carter, anti-fascist Liberal politician. Referred to as "an Encirclement lady politician"[37]

- William Henry Bragg, physicist, chemist, mathematician, sportsman and Nobel prize winner[38]

- Vera Brittain, feminist writer and pacifist[39]

- Fenner Brockway, socialist and politician.[40]

- "Harry Bullock", thought to be a mistake for Guy Henry Bullock, diplomat and Everest mountaineer[41][42]

- Neville Chamberlain, "political, former prime minister",[18][43] died 9 November 1940

- Sydney Chapman, economist and civil servant[43]

- Winston Churchill, prime minister[43][44]

- Sir Walter Citrine, trade unionist[45]

- Marthe Cnockaert, First World War spy[46]

- Claud Cockburn, journalist[46]

- Seymour Cocks, Labour politician[46]

- Chapman Cohen, secularist writer and editor [47]

- Lionel Leonard Cohen, lawyer[46]

- Robert Waley Cohen, industrialist[46]

- G. D. H. Cole, academic[46]

- Norman Collins, broadcasting executive[46]

- Edward Conze, Anglo-German scholar[46]

- Duff Cooper, Minister of Information[46]

- Pierre Coalfleet, aka Frank Davison, writer[48]

- Margery Corbett Ashby, feminist[46]

- Noël Coward, high-profile actor and armed forces entertainer who opposed appeasement; connections with MI5[43][49]

- Sir Stafford Cripps, Labour politician[45]

- Nancy Cunard, writer, heiress and anti-fascist[50]

- Frederick Francis Charles Curtis, architect[48][51]

- Sefton Delmer, journalist[52]

- Peter Drucker, author[53]

- Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for War[54]

- Jacob Epstein, sculptor[49]

- Lion Feuchtwanger, German Jewish novelist and playwright[55]

- Frank Foley, spy who as MI6 Head of Station in pre-war Berlin rescued thousands of German Jews[56]

- E. M. Forster, author[56]

- Sigmund Freud, Jewish founder of psychoanalysis (died 23 September 1939)[57]

- Willie Gallacher MP, trade unionist and communist politician[58]

- Charles de Gaulle, Free French leader and general, listed as "former French General"[44]

- Sir Philip Gibbs, journalist and novelist[59]

- Victor Gollancz, publisher[60]

- J. B. S. Haldane, geneticist, evolutionary biologist and communist[61]

- Ernst Hanfstaengl, German refugee. Once a financial backer of Hitler, he had fallen from favour and had fled Germany in 1937[61]

- Aldous Huxley, author (who had emigrated to the US in 1936)[49][62]

- Cyril Edwin Joad, educator[63]

- Egon Erwin Kisch, Austrian-Czechoslovak Jewish writer and journalist, listed as "Egon Erwin Kich"[64]

- Alexander Korda, Hungarian-born British producer and film director[65]

- George Lansbury, "rules German emigrant political circles"[18]

- Harold Laski, political theorist, economist and author[63][66]

- Megan Lloyd George, politician, daughter of David Lloyd George, who was not on the list[15]

- David Low, political cartoonist and caricaturist[49][67]

- F. L. Lucas, literary critic, writer and anti-fascist campaigner[67]

- Geoffrey Mander, Liberal politician (critic of Appeasement and crusader on behalf of the League of Nations), manufacturer and art collector.[68]

- Heinrich Mann, German novelist and anti-fascist[69]

- Jan Masaryk, foreign minister of the Czechoslovak government in exile[70]

- Jimmy Maxton, pacifist politician[71]

- Naomi Mitchison, novelist[72]

- Gilbert Murray, classical scholar and activist for the League of Nations[73]

- Harold Nicolson, as "Nicholson", diplomat, author and diarist[74]

- Philip Noel-Baker, Labour politician[63]

- Conrad O'Brien-ffrench, SIS/MI6 Agent ST36, Agent Z3 for Dansey's Z Organization[57]

- Vic Oliver, British actor and radio comedian, originally from Austria and married to Winston Churchill's daughter Sarah, listed as "Olivier, Jewish actor".[26][75]

- Ignacy Jan Paderewski, pianist, former prime minister of Poland[76]

- R. Palme Dutt, journalist and theoretician of the Communist Party of Great Britain[77]

- Sylvia Pankhurst, suffragist, writer, journalist and anti-fascist[78]

- Nikolaus Pevsner, German (and later British) architectural historian[79]

- Michael Polanyi, British polymath, originally from Hungary.[80]

- Harry Pollitt, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain[81]

- Thomas Hildebrand Preston, 6th Baronet, diplomat[80]

- J. B. Priestley, creator of anti-Nazi popular broadcasts and fiction[82]

- Eleanor Rathbone MP, activist for assistance to refugees[83]

- Hermann Rauschning, German refugee and once personal friend of Hitler who had turned against him[83]

- Douglas Reed, journalist and author[49][83]

- Paul Robeson, African-American singer/actor with strong Communist affiliations[49][84]

- Dr Agnes Maude Royden, suffragist, author, preacher, philosopher, pacifist[85][86]

- Sir Thomas Royden, director and former chairman of Cunard Line (brother of Maude Royden)[87]

- Bertrand Russell, philosopher, historian and pacifist[85]

- Duncan Sandys, Conservative politician listed as "Dunkan Sandys"[26]

- John Segrue, foreign correspondent for the News Chronicle[88][89]

- Adolf Schallamach, scientist[90]

- Dr. Francis Simon, a German and later British physical chemist and physicist[91]

- Sir Archibald Sinclair, Liberal politician[45]

- Robert Smallbones, diplomat who granted visas to 48,000 Jews, recognized in 2010 as a British Hero of the Holocaust[92]

- Aline Atherton-Smith, Quaker[93]

- C. P. Snow, physicist and novelist[94]

- Stephen Spender, poet, novelist and essayist[95]

- Lytton Strachey, died 1932, writer and critic[96]

- Sybil Thorndike, actress[49][97]

- Frank Cyril Tiarks, banker, director of the Bank of England, member British Union of Fascists and Anglo-German Fellowship.[98]

- Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus, politician, former German minister[99][100]

- Lord Vansittart, "leadership of British Intelligence Service, Chief Diplomatic Adviser to the Foreign Office"[18]

- Beatrice Webb, socialist and economist[63][101]

- Dr. Chaim Weizmann, Russian-born British lecturer and Zionist leader who had worked in Germany; later President of Israel[63][102]

- H. G. Wells, author and socialist[102]

- Rebecca West, suffragist and writer[49][102]

- Ted Willis, dramatist[103]

- Leonard Woolf, political theorist, author, publisher, and civil servant, husband of Virginia Woolf[104]

- Virginia Woolf, novelist and essayist, wife of Leonard Woolf[104]

- Alfred Zimmern, classical scholar, historian and political scientist[105][106]

- Carl Zuckmayer, German writer and playwright[105][107]

- Leonie Zuntz (1908–1942), German Hittitologist, refugee scholar at Somerville College, Oxford[108]

- Stefan Zweig, Austrian Jewish writer[105]

See also

[edit]- Special Prosecution Book-Poland (German: Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen)

- Dr. Franz Six, SS official appointed by Reinhard Heydrich to direct state police operations in German-occupied Great Britain.

- Bibliography of the Holocaust § Primary Sources

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Philip Gooden; Peter Lewis (25 September 2014). The Word at War: World War Two in 100 Phrases. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-4729-0490-4.

- ^ Shirer 1964, pp. 937–938.

- ^ a b c Reinhard R. Doerries (18 October 2013). Hitler's Intelligence Chief: Walter Schellenberg. Enigma Books. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-936274-13-0.

- ^ Shirer 1964, pp. 937, 939.

- ^ Guardian 1945, para 1, 13–15.

- ^ a b Forces War Records 2017.

- ^ Fleming 1975, pp. 35–41.

- ^ Fleming 1975, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Fleming 1975, pp. 192–195.

- ^ Schellenberg, Walter (1956). The Schellenberg Memoirs. London: Andre Deutsch. OCLC 1072338372.

- ^ Schellenberg 2000.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 150.

- ^ a b Imperial War Museums.

- ^ a b Hoover Institution Library.

- ^ a b Dalrymple, James. Fatherland UK, The Independent, 3 March 2000

- ^ a b Noël Coward, Future Indefinite. London; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014 ISBN 1408191482 (p. 92).

- ^ Guardian 1945, para 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Guardian 1945, para 10.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book - information for Lascelles Abercrombie". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for David Adams". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Vyvyan Samuel Adams". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Jennie Adamson". Forces War Records. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Christopher Addison". Forces War Records. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Doctor Friedrich Adler". Forces War Records. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Nettie Adler". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Guardian 1945, para 8.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book - information for Leopold Amery". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Fergus Anderson". Forces War Records. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 160.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Doctor Friedrich Antal". Forces War Records. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for John Astor". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Catherine, Duchess of Atholl". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 162.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 165.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for John D Professor Bernal". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 168.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 170.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Fenner Brockway". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 171.

- ^ "If Britain had been conquered. 2,300 names on Nazi Black List". Dundee Evening Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 14 September 1945. p. 8. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d Schellenberg 2001, p. 173.

- ^ a b Guardian 1945, para 6.

- ^ a b c Guardian 1945, para 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schellenberg 2001, p. 174.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Chapman Cohen". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Guardian 1945, para 9.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Nancy Cunard". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Doctor Frederick F. C. Curtis". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 177.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 179.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 181.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Lion Feuchtwanger". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 186.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 187.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 190.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 191.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 192.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 195.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e Guardian 1945, para 12.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Egon Erwin Kich". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 213.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 217.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Geoffrey Mander". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Heinrich Mann". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 221.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 222.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 223.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 226.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 230.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Palme R Dutt". Forces War Records. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ D. Mitchell, The fighting Pankhursts, Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1967, p. 263

- ^ Brian Harrison, "Pevsner, Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon (1902–1983)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 233.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Harry Pollitt". Forces War Records. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 234.

- ^ a b c Schellenberg 2001, p. 235.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 237.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 239.

- ^ Liverpool Evening Express. 14 September 1945. para 9.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Thomas Royden". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book - information for J. C. Segrue". Forces War Records. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book - information for Segrue John Chrisoton". Forces War Records. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 246.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 242.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 243.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book - information for Aline Sybil Atherton-Smith". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 244.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 249.

- ^ Fearn, Nicholas. "A travel guide for Nazis". The Daily Telegraph, 18 March 2000

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 253.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Frank Tiarks". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 255.

- ^ Lawrence D. Stokes. "Secret Intelligence and Anti-Nazi Resistance. The Mysterious Exile of Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus". In The International History Review, Vol. 28, No. 1 (March 2006), p. 60.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Schellenberg 2001, p. 260.

- ^ Schellenberg 2001, p. 261.

- ^ a b Schellenberg 2001, p. 262.

- ^ a b c Schellenberg 2001, p. 265.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Alfred Zimmern". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Karl Zuckermeyer". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Hitler's Black Book – information for Doctor Leonie Zuntz". Forces War Records. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Schellenberg, Walter (2001). Invasion 1940: The Nazi Invasion Plan for Britain. St Ermin's Press. ISBN 978-0-9536151-3-1. OCLC 45488085.

Schellenberg, Walter (2000). Invasion 1940: The Nazi Invasion Plan for Britain. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-3168531-5-6. OCLC 43341989. - Shirer, William L. (1964). "Chapter 22: If the invasion had succeeded". The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Pan Books. pp. 936–940. OCLC 462490002. – Discusses the black book and its contents.

Shirer, William L. (23 October 2011). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. RosettaBooks. ISBN 978-0-7953-1700-2. OCLC 995602547. - Fleming, Peter (1975). Operation Sea Lion : an account of the German preparations and the British counter-measures. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-24211-3.

- Guardian (14 September 1945). "Nazi's black list discovered in Berlin". Guardian Century - 1940-1949. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Forces War Records (28 February 2017). "Hitler's Black Book - List of Persons Wanted". Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017. – complete list of names

- Hoover Institution Library. "Die Sonderfahndungsliste G.B." Hoover Institution Library and Archives.

Vault DA585 .A1 G37 (V), 376 p. 19 cm. On cover: Geheim!, 'Gestapo arrest list for England' in ms. on cover.

- Imperial War Museums. "Die Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. : [the Black Book] (LBY 89 / 1936)". Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Black Book: Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. Facsimile reprint series (in German). London: Imperial War Museum, Department of Printed Books. 1989. ISBN 978-0-901627-51-3.

Facsimile reprint of the original produced by the Reichssicher-heitshauptamt in May 1940. It features an introduction explaining the origins of the 'Special Search List GB'. Original (41820) in Special Collection

- Black Book: Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. Facsimile reprint series (in German). London: Imperial War Museum, Department of Printed Books. 1989. ISBN 978-0-901627-51-3.