Crusading movement

The crusading movement encompasses the framework of ideologies and institutions that described, regulated, and promoted the Crusades. The crusades were religious wars that the Christian Latin church initiated, supported, and sometimes directed in the Middle Ages. The members of the church defined this movement in legal and theological terms that were based on the concepts of holy war and pilgrimage. In theological terms, the movement merged ideas of Old Testament wars that were believed to have been instigated and assisted by God with New Testament ideas of forming personal relationships with Christ. The institution of crusading developed with the encouragement of church reformers the 11th century in what is commonly known as the Gregorian Reform and declined after the 16th century Protestant Reformation.

The idea of crusading as holy war was based on the Greco-Roman Just war theory. A "just war" was one where a legitimate authority is the instigator, there is a valid cause, and it is waged with good intentions. The Crusades were seen by their adherents as a special Christian pilgrimage – a physical and spiritual journey authorised and protected by the church. The actions were both a pilgrimage and penitental, Participants were considered part of Christ's army and demonstrated this by attaching crosses of cloth to their outfits. This marked them as followers and devotees of Christ and was in response to biblical passages exhorting Christian "to carry one's cross and follow Christ". Everyone could be involved, with the church considering anyone who died campaigning a Christian martyr. This movement was an important part of late-medieval western culture, that impacted politics, the economy and wider society.

The original focus and objective was the liberation of Jerusalem and the sacred sites of Palestine from non-Christians. The city was considered to be Christ's legacy and it was symbolic of divine restoration. The site of Christ's redemptive acts was pivotal for the inception of the First Crusade and the subsequent establishment of crusading as an institution. The campaigns to reclaim the Holy Land were the ones that attracted the greatest support, but the crusading movement's theatre of war extended wider than just Palestine. Crusades were waged in the Iberian Peninsula, northeastern Europe against the Wends, the Baltic region, campaigns were fought against those the church considered heretics in France, Germany, and Hungary, as well as in Italy where Pope's indulged in armed conflict with their opponents. By definition all the crusades were waged with papal approval and through this reinforced the Western European concept of a single, unified Christian church under the Pope.

Major features[edit]

Historians trace the beginnings of the crusading movement to the significant changes within the Latin church enacted during the mid and latter eleventh century.[3] These are now known as the Gregorian Reform, from a term popularised by the French historian Augustin Fliche. He named the changes after one of the leading reforming popes Gregory VII. The use of the term oversimplifies what was in fact numerous discrete initiatives, not all of which were the result of papal action.[4]

A group of reformers took control of the governance of the church with ambitions to use this control to eradicate behaviour they viewed as corrupt.[3] This takeover was initially supported by the Holy Roman Empire and by Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor in particular, but went on to lead to conflict with his son, Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. The reformers believed in papal primacy. That is the Pope was the head of all of Christendom as heir of St Peter. Secular rulers, even including the emperor, were subject to this and could be removed.[5]

The reformist groups opposed previously widespread behaviour such as the sale of clerical positions and clerical marriage.[6] The changes were not without opposition, causing splits within the church and between the church and the emperor.[7] However, the reform faction successfully created the ideology for men they saw as God's agents. From the second half of the 11th century, it enabled them in the refashioning of the church along the moral and spiritual lines they believed in.[8] Historians consider that this was a pivotal moment, because the church was now under the control of men who supported a concept of holy war and would plan to make it happen.[9]

The reformers now viewed the church as an independent force with God given authority to act in the secular world for religious regeneration. The creation of the institutions of crusading were a means by which the church could act militarily with the support of the armed aristocracy. This would in turn lead to creation of formal processes for the raising of armed forces through which the church could enforce its will. While these fundamentals applied the crusading movement flourished, when they ceased to be significant the movement declined.[10][11]

Penance and indulgence[edit]

Before the crusading movement was established, the church had developed a system that enabled Christians to gain forgiveness and pardon for sins from the church on behalf of God. They did this by demonstrating genuine contrition through admissions of wrongdoing and acts of penance. Christianity's requirement to avoid violence was still a significant issue for the warrior class. Gregory VII offered them a potential solution In the latter part of the 11th century. This was that they too could have their sins forgiven if they supported him in fighting for papal causes, but only if this service was given altruistically.[12][13] Later popes expanded on this offer to those willing to fight for their causes. Urban II launched the First Crusade at Clermont in November 1095. He made two offers to those who would travel to Jerusalem and fight for control of the sites Christians considered sacred. They were that those who fought would receive exemption from penance for the sins they committed and while they fought the church would protect all their property from harm.[14] The enthusiasm of the crusading movement challenged what had been conventional theology. This can be seen in a letter from Sigebert of Gembloux to Robert II, Count of Flanders. Sigebert is critical of Pope Paschal II and in congratulating Robert on his safe return from Jerusalem he pointedly omits any reference at all of the fact that Robert had been fighting on a crusade.[15]

Later pope's would develop the institution even further. Not only would crusaders avoid what were considered the God-imposed punishments for their sins but the guilt and the sin itself would be expunged. The method through which this was achieved was the granting by the church of what was called a plenary indulgence.[16] Calixtus II made the same offer privileges and extended the protection of property to crusaders' relations.[17] Innocent III reinforced the importance of the oaths crusaders took. He also emphasised the view the forgiveness of sin was a gift from God. It was not considered a reward for the suffering endured by the crusader while on crusade.[18][19] It was in the 1213 papal bull called Quia maior that he reached out beyond the noble warrior class. He offered all other Christians the opportunity to redeem their vows without even going on crusade. This led to the unforeseen consequence of creating a market for religious rewards. This would later scandalise some devout Christians and through this become a contributing factor for the Protestant Reformation from the 16th century.[20][21] As late as the 16th century, some writers continued to seek atonement for their sins through the practice of crusading. At the same time John Foxe the English martyrologist and others saw this as "the impure idolatry, and profanation"[22]

Popes continued in the practice of issuing crusade bulls for generations, but Alberico Gentili and Hugo Grotius created an international rule of law that was secular rather than religious.[23] The wars against the Ottoman Empire and in defence of Europe were conflicts on which Lutherans, Calvinists, and Roman Catholics could agree in principle. So the importance to recruitment of the granting of indulgences became increasingly redundant and declined.[24]

Christianity and war[edit]

The 4th-century theologian Augustine of Hippo Christianised theories of bellum justum or just war that dated from the Greco-Roman world. In the 11th century canon lawyers extended his thinking to create the paradigm of bellum sacrum, or a form of Christian holy war.[25] The theory was based on the idea that Christian warfare could be justified even though it was considered a sin. It was necessary to meet three criteria if a war was to be considered just. Firstly, it must be declared by an authority that the church considered legitimate. Secondly, the war must have defensive objectives or to be for the recovery of stolen property and rights. Lastly, the intentions of those taking part must be good.[26][27]

Using these theories the church supported various Christian groups in conflicts with their Muslim neighbours at the borders of Christendom. In what is now Northern Spain encouragement was given during the siege of Barbastro. The Normans of Southern Italy were supported in their conquest of the Emirate of Sicily. Gregory VII even planned to lead a campaign himself in support of the Byzantine Empire in 1074. He was unable to gather the necessary support, possibly because his personal leadership was unacceptable. Despite this, his plans did leave a template for future crusades.[28] As did the campaigns in Spain where leading thinkers and fighters developed practical and fundamental arguments for the crusading movement.[29]

The thoughts and writing on these theories were eventually consolidated into Collectio Canonum or Collection of Canon Law by Anselm of Lucca.[12] Thomas Aquinas and others extended these theories in the 13th century. This created a concept of religious war. [30] This enabled various popes to use canon law in the call for crusades against their enemies in Italy. Rome was the estate of St Peter, so the popes' campaigns were defensive and only fought for the preservation of Christian territory.[31] The church combined two themes in the creation of crusading, one from the Old Testament and one from the New. The first was the wars of the Jews. These were believed to have come from the instigation and will of God. The second was the Christocentric ideas related to Christians forming individual relationships with Christ. It was believed these were instigated and assisted by God. Secondly, the Christocentric concept of forming an individual relationship with Christ that came from the New Testament. In this way the church was able to combine the ideas of holy war and Christian pilgrimage to create the legal and theocratic justifications for the crusading movement.[25]

The historian Carl Erdmann mapped out the three stages for the argument creating the institution of the crusading movement:

- defending Christen unity was a just cause;

- that Pope Gregory I and his followers' ideas for missionary conquest was also in accordance;

- that Islam should be fought in defence of Christendom, an idea developed under the reformist popes Leo IX, Alexander II, and Gregory VII.[32]

Knights, chivalry and the military orders[edit]

Innovations in military technology and thinking made the first crusades feasible. Tactics developed to utilise heavily armoured cavalry. Italy's maritime republics built increasingly large navies. Society was controlled by castles and the men who garrisoned them. These new techniques in turn developed new social mores developed during extensive training. In turn this led to the rise of combat as sport.[33] At this time although knights were praised in literature they remained distinct from the aristocracy. Crusading and chivalry developed together, and in time chivalry helped shap the ethos, ideals and principles of crusaders.[34] Tournaments were held where knights could exhibit their martial prowess. This provided venues where the crusading movement could recruit, spread propaganda and announce the enlistment of senior figures.[35] Despite the undoubted courage and commitment of crusading knights and some notable commanders in military terms the campaigns in the Levant were not typically impressive. The creation of disciplined units was challenging. In feudal Europe strategy and institutions were too immature. Power structures were too fragmented.[36]

Literature presented the exemplar of an idealised, perfect knight in works such as romance Alexandre written around 1130. These works extolled adventure, courage, charity and manners. The church could not accept readily all the values presented. Its spiritual views contrasted with ideas of excellence, achieved glory through military deeds and romantic love. Even though the church feared the warrior class it needed to co-opt its power and did this symbolically through developed liturgical blessings to sanctify new knights.[37] In time kings represented themselves as members of the knighthood for propaganda purposes.[38] Crusading became seen as integral to the ideas of this ideal.[39] From the time of the Fourth Crusade, it became an adventure normalised in Europe, creating separation between the knights and other social classes. At this point the relationship between knightly adventure, religious, and secular motivation was altered.[40]

In the polities created by the crusading movement in the Eastern Mediterranean known as the Crusader states the creation of military religious orders was one of the few innovations from outside Europe.[41] In 1119 a small band of knights formed to protect pilgrims journeying to Jerusalem. These became the Knights Templar. Many other orders followed this template. The Knights Hospitaller were providing medical services and added a military wing to become a much larger organisation. These orders became Latin Christendom's first professional fighting forces and played a major part in the defence of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other crusader states.[42] Papal acknowledgement encouraged significant donations of money, land and recruits from across western Europe. The orders built their own castles and developed international autonomy.[43]

When Acre fell, bringing to a close the holding of Christian territory in the Holy Land the Hospitallers relocated to Cyprus. Later the order conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and finally settled in Malta (1530–1798). The orders successor organisation, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta still exists today. King Philip IV of France extinguished the Templars around 1312. This was probably for financial and political reasons. He pressurised Pope Clement V to dissolve the order. The grounds of sodomy, magic, and heresy listed in various papal bulls such as Vox in excelso and Ad providam were probably false.[44]

Common people[edit]

Historians now take a greater interest than before questioning why significant numbers of the lower classes travelled on the early crusades or took part in the unsanctioned popular outbreaks of the 13th and 14th centuries.[45] The papacy wanted to recruit warriors who could fight, but in the early years of the movement it was impossible to exclude others, including women. Indeed, retinues included many to provide services who could also fight in emergencies.[46] The church considered that engaging in crusade must be entirely voluntary. Recruitment propaganda used understandable mediums which could also be unclear. For the poor the instituition of the crusade was offensive, while in church doctrines it was an act of self-defence.[45]

From the 12th century onwards the crusading movement generated propaganda material to spread the word. A good example was the work of a Dominican friar called Humbert of Romans. In 1268 he gathered the best crusading arguments in one work.[47][48] The poor had different viewpoints to the theologans. Often based on an end of the world eschatological belief. When Acre was lost to the Egyptians there were resulting popular but brief outbursts of crusade fervour.[49] However, the most Christians did not typically crusade to Jerusalem. Instead, they would often build models of the Holy Sepulchre or dedicate places of worship. These were acts theat existed before the crusading movement, but they became increasingly popular in association. They may have formed part of other forms of regular religious devotion. In 1099 Jerusalem was known as the remotest place but these practices made tangible crusading.[50]

Unsanctioned popular crusading exploded in 1096, 1212, 1251, 1309, and 1320. These all exhibited violent antisemitism with the exception of the Children's Crusade of 1212. Despite hostility from the literate these crusades became so mytho-historicised in the written histories that they are some of the most highly remembered events transmitted by word of mouth from the period. That said "Children's Crusade" is not a precise definition. At the time the Latin pueri was used for children;peregrinatio, iter, expeditio, or crucesignatio were used for crusade.[51]

The many surviving written sources are of questionable accuracy. Dates and details are not consistent and they are interwoven with typical myth-history stories and ideas.[52] Clerical writing contrasted the imagined innocence of the pueri with the sexual license that was seen on the official crusades. It was the sin of the crusaders that was believed to bring God's displeasure and explain why the crusades were not successful.[53]

Perception of Muslims[edit]

Literature such as the 11th century chanson de geste Chanson de Roland did not explicitly mention the crusades. But is likely there were propaganda motivations behind presenting the Muslim characters in monstrous terms and as idolators. Whatever the motivation Christian writers continued to use these representations.[54] Muslim characters were described as evil and as less than human. Their physical appearance was described as devilish and they were represented as having dark skin. Islamic ritual was mocked and insults made to Mohammad. This caricature continued to be used long after the fighting over territory subsided. At no time was the noun Muslim used, instead Muslims were called Saracens. Other derogatory adjectives were also used, such as infidel, gentile, enemy of God, and pagan. This was literature that supported the church's opinion that the crusades were a Manichean contest between good and evil.[55] According to the historian Jean Flori the purpose behind this was for the church to be able to destroy its ideologically is competitors for the purpose of justifying Christianity entry into aggressive violent conflict.[56] This prejudice was not derived from ethnic identity or race. The church considered that all of humanity were descended from Adam and Eve. Typical of medieval opinion this was a social construct in which the differentiators were cultural. For example, the First Crusade Chroniclers adopted terminology inherited from the Greeks of antiquity. They use the ethnology-cultural term barbarae nationes or barbarians for the Muslims, and self-identified crusaders as Latins.[57]

As contact increased respect for the Turks developed. Gesta Francorum presents some negativity but also respect for them as opponents. It was considered values of chivalry were shared. In the Chanson d'Aspremont they were presnted as equals following the same codes of conduct. By the time of the Third Crusade the class differences were shown as within camps rather the between camps. The elite warrior class in both camps shared an identity that was not divided on religious or political groups. Epics began to include incidents of conversion to Christianity. This in part may have offered hope for a positive resolution at a time when military failure pointed to defeat.[58]

There remain a number of Crusade songs from the many crusaders who also wrote poetry such as Theobald I of Navarre, Folquet de Marselha, and Conon de Béthune. In return for patronage from the leaders of the crusades, poets wrote praising the ideals of the nobility.[59] These relationships were of a feudal nature and were presented in this context. To demonstrate this the crusaders were God's vassals fighting the restore to him the (Holy) land.[60] Muslims were presented as having stolen this land. Their mistreatment of its Christian inhabitants was considered an injustice for which revenge was required. In return, the perception of the Islamic polities resulted in an opposing position. This encouraged violent resistance to the idea of the imposition Christian governance on these terms.[61]

History[edit]

In the late 11th and early 12th century the papacy became an entity capable of organised violence in the same manner as secular kingdoms and principalities. This required command and control systems that were not always fully developed or efficient. The result was the papacy leading secular fighting forces for its own ends.[62]

This was begun by Pope Alexander II around 1159. He involved the papacy in the long running conflict with Muslims in the Mediterranean region. The church became involved in, and gave approval for, campaigns in Sicily, Spain and North Africa where the church worked with the republics of Pisa and Genoa.[63]

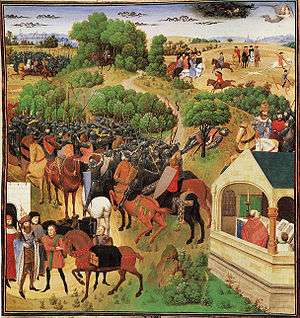

Urban II laid the foundations of the crusading movement at the Council of Clermont in 1095. He was responding to requests for military support from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos that he received during the earlier Council of Piacenza. Alexios was fighting Turkish people who were migrating into Anatolia, threatened Constantinople and had formed the Seljuk Empire. Urban expressed two key objectives for the crusade. Firstly, the freeing of Christians from Muslim rule. Secondly, freeing the church known as the Holy Sepulchre from Muslim control. This was believed to mark the location of Chris's tomb in Jerusalem.[64][2]

In the 12th century, Gratian and the Decretists elaborated on Augustinianism. Aquinas continued this in the 13th century.[65] This extended the reformers philosophy to end secular control of the Latin church and impose control over the Eastern Orthodox Church. It developed further the paradigm of working in the secular world for the imposition of what the church considered justice.[66] After the initial success of the early crusades the settlers who remained or later migrated were militarily vulnerable. During the 12th and 13th centuries, frequent supportive expeditions were required to maintain territory that had been gained. A cycle developed of military failure, pleas for support and declarations of crusades from the church.[67]

12th century[edit]

The success of the First Crusade that began the crusading movement and the century was seen as astonishing. The explanation for this was given that it was only possible through the will of God.[68] Paschal succeeded Urban as pope before news of the outcome reached Europe. He had experience of the fighting in Spain so readily applied similar remissions of sin to the combatants there, without the need for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[69] He did not stop there with the application of the institutions of crusading. He also did this against the Orthodox christians of Byzantium in favour of Bohemond I of Antioch for political reasons in Italy.[70]

It was in certain social and feudal networks that early crusade recruitment concentrated. Not only did these groups provide manpower, but also funding. Although it may have been pragmatic acceptance of the pressure of the reform movement that prompted the sales of churches and tithes. These families often had a history of pilgrimage, along with connections to Cluniac monasticism and the reformed papacy. They honoured the same saints. With inter-marriage this cultural mores were spread through society.[71] Paschal's successor Pope Calixtus II shared his Spanish interests. In 1123, at the First Council of the Lateran it was decided that crusading would be deployed in both Iberia and the Levant. The outcome was a campaign by Alfonso the Battler against Granada in 1125.[17][69]

The crusaders established polities known as the Latin East, because it was impossible to defend Jerusalem in isolation. Despite this, regular campaigns were required in addition to the capability provided by the military orders. In Spain further expeditions were launched in 1114, 1118, and 1122. Eugenius III developed an equivalence between fighting the Wends, fighting the Muslims in Spain and the Muslims in Syria. The later crusade failed, with the result that the movement suffered its largest crisis until the 1400s. Fighting continued in Spain where there was three campaigns and there was one in the East in 1177. But it was the news of the crusaders defeat by the Muslims at the Battle of Hattin that restored the energy and commitment of the movement.[17]

The Renaissance of the 12th century coincided with the early years of crusading. Crusading themes were the subject of developing vernacular literature in the languages of Western Europe. Examples of Epic poetry include the Chanson d'Antioche describing the events in the 1268 siege of Antioch and Canso de la Crozada about the crusading against the Cathars in Southern France. These are given the collective name of Chansons de geste in the French language which is borrowed from Latin for the term deeds done.[72] Surviving songs about Crusading are rarer. But there are examples in the literary language of southern France, Occitan, French, German, Spanish, and Italian that touch on the topic in an allegorical that date from the later half of the century. Two notable Occitan troubadours were Marcabru and Cercamon. They composed songs in the styles called sirventes and pastorela on the subject of lost love. Crusading wasn't a distinct genre, but the subject. The troubadours had northern French equivalents called Trouvère and German ones called Minnesänger. Collectively they left bodies of works themed on the crusades later in the century.[73] This material transmitted information about crusading unmediated by the church. It is reinforced the status quo, the class identity of the nobility and its position in society. When the outcomes of events was less positive this was also a method of spreading criticisms of organisation and behaviour.[74]

In the latter part of the century Europeans developed language, fashion and cultural mores for crusading. Terms were adopted for those involved such as crucesignatus or crucesignata. These indicated that they were marked by the cross. This was reinforced by cloth crosses that they attached to their clothes. All of this was taken from the Bible. Luke 9:23, Mark 8:34 and Matthew 16:24 all implored believers to pick up their cross and follow Christ.[75][76] It was a personal relationship with God that these crusaders were attempting to form. It demonstrated their belief. It enabled anyone to become involved, irrespective of gender, wealth, or social standing. This was imitatio Christi, an "imitation of Christ", a sacrifice motivated by charity for fellow Christians. It began to be considered that all those who died campaigning were martyrs.[77]

13th century[edit]

Towards the end of the 12th century the crusading movement existed in a culture where is was believed that everything that happened was predestined, either by God or fate. This Providentialism meant that the population welcomed, accepted and believed in a wide range of prophecy. One significant example of this was the writing of Joachim of Fiore. He included the fighting of the infidel in opaque works that combined writings on the past, on the present, and on the future.[78] These works foreshadowed the Children's Crusade. Joachim believed all history and the future could be divided into three ages. The third of these was the age of the Holy Spirit. The representatives of this age were children, or pueri. Others aligned themselves to this idea. Salimbene and other Franciscans self described themselves as ordo parvulorum. This translates as order of little ones. Another example of this Apocalypticism can be seen in elements of the Austrian Rhymed Chronicle. In this apocalyptic mytho-history was melded to descriptions of the Children's Crusade. Innocent III built on this in 1213 announcing the end of Islam in the calls for the Fifth Crusade by announcing that the days of were over.[79]

The crusading movement found that creating a single accepted ideology and an understanding of that ideology was a practical challenge. This was because the church did not have the necessary bureaucratic systems to consolidate thinking across the papacy, the monastic orders, mendicant friars, and the developing universities.[80] Ideas were transmitted through inclusion in literary works that included romances, travelogues like Mandeville's Travels, poems such as Piers Plowman and John Gower's Confessio Amantis, and works by Geoffrey Chaucer.[81][82][83][84] At this point in time the ideas of nationalism were largely absent. A more atomised society meant that literature tended to rather praise individual deeds of heroes like Charlemagne and the actions of major families.[85] Innocent III developed new practices and revised the ideology of crusading from 1198 when he became pope. This included a new executive office constituted for the organisation of the Fourth Crusade. Executives were appointed in each church province in addition to autonomous preaching by the like of Fulk of Neuilly. This led to papal sanctioned provincial administrations and the codification of preaching. Local church authorities were required to report to these administrators on crusading policy. Propaganda was now more coherent despite an occasionally ad-hoc implementation.[86] Funding was increased through the introduction of hypothecated tax and greater donations.[18][19] He was also the first pope to deploy the apparatus of crusading against his fellow Christians.[20][21] This innovation became a frequent approach by the papacy that was used against those it considered dissenters, heretics, or schismatics.[87]

Popular crusading[edit]

In 1212 there was an outbreak of popular crusading that is now known as the Childrens' crusade. This was the first of a number of similar events which lasted until 1514 the Hungarian Peasants' Crusade. What these all had in common was that they were independent of the church. The first seems to have been a response to the preaching of the Albigensian Crusade and also religious processions seeking God's support for the fighting in Iberia. The church considered such outbreaks by rather unconventional crusaders as unauthorised and therefore illegitimate.[88] There is little remaining evidence for the identities, thoughts and feelings of those who took part.[89] One unaccredited piece is the Austrian Rhymed Chronical. This includes alledgedly verbatim lyrics of the marching song of children heading east and offers evidence of eschatological beliefs.[90] The church was unable to comprehend the charisma of impoverished secular leaders like Nicholas of Cologne and how this could be used in recruiting such large followings.[91] Modern academic opinion is split on the definition of a crusade. Riley-Smith disregards these popular uprisings as not meeting the criteria, while Gary Dickson has produced in depth research.[92]

Early century[edit]

In the years between 1217 and 1221 Cardinal Hugo Ugolino of Segni led preaching campaigns and helped relax controls on funding and recruitment. He used the five percent income tax on the church known as the "clerical twentieth" to pay mercenaries in the Fifth Crusade and other crucesignati.[93] In 1227, Hugo became pope and adopted the name Gregory IX.[94] He clashed with Frederick II over territory in Italy, excommunicating him in 1239 and deploying the crusading tools of indulgences, privileges, and taxes in 1241.[95][96] The Christian right to land ownership was foundational to crusading ideology, although Innocent IV acknowledged Muslim rights he considered these only existed under the authority of Christ.[97] Alexander IV continued the policies of both Gregory IX and Innocent IV from his ascension in 1254 which led to further crusading against the Hohenstaufen dynasty.[98]

Criticism[edit]

During 12th and 13th centuries the concepts behind the crusading movement were rarely questioned, but there is evidence that practice was criticised. Events such as crusades against non-conforming Christians, the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade, crusading against the German Hohenstaufen dynsaty and the southern French Albigensian all drew condemnation. Questions were raised about the objectives of these and whether they were a distraction from the primary cause of fighting for the Holy Land. In particular, Occitan Troubadours expressed discontent with expeditions in their southern French homeland. Additionally, reports of sexual immorality, greed, and arrogance exhibited by crusaders was viewed as incompatible with the ideals of a holy war. This gave commentators excuses or reasons for failures and setbacks in what was otherwise considered God's work. In this was defeats experienced such as during the First Crusade, by Saladin at Hattin and the defeat of Louis IX of France at the Battle of Mansurah (1250) could be explained. Some, such as Gerhoh of Reichersberg, linked this to the expected coming of the Antichrist and increased puritanism. [99][100] This puritanism was the church's response to criticism, and included processions and reforms such as gambling bans and restrictions on women. Primary sources include the Würzburg Annals and Humbert of Romans's work De praedicatione crucis which translates as concerning the preaching of the cross. Crusaders were thought to have fallen under satanic influence and doubts were raised about forcible conversion.[101]

Later century[edit]

The movement continued developing innovative organisational financial methods. However in 1274 it faced a significant low.[102] In response the Second Council of Lyons initiated the search for new ideas> The response to which showed a resilience that would enable the continuation of the movement.[102] This was not without opposition. Matthew Paris in Chronica Majora and Richard of Mapham, the dean of Lincoln both raised note worthy concerns and the Teutonic Order for one, amongst others of the military orders were criticised for arrogance, greed, using their great wealth to pay for luxurious lifestyles, and an inadequate response in the Holy Land. Collaboration was difficult because of open conflict between the Templars and Hospitallers and among Christians in the Baltic. The autonomy of the orders was viewed in the church as leading to a loss of effectiveness in the East and overly friendlt relations with Muslims. A minority within the church including Roger Bacon made the case that aggression in areas like the Baltic actually hindered conversion.[103] Pope Gregory X developed the objective of reunification with the Greek church as an essential prerequisite for further crusades.[104] In planning the funding of this crusade he created a complex tax gathering regime by Latin Christendom into twenty-six collectorates, each directed by a general collector. In order to tackle fraud each collector would further delegate tax liability assessment. This system raised vast amounts which in turn prompted further clerical criticism of obligatory taxation.[105]

14th century[edit]

Between the councils of Lyon in 1274 and Vienna in 1314, there existed over twenty treatises concerning the recovery of the Holy Land. These were instigated by Popes who, following the lead of Innocent III, sought counsel on the matter. This led to unfulfilled strategies for the blockading Egypt and possible expeditions to establish a foothold that would pave the way for full-scale crusades with professional armies. Discussions among writers often revolved around the intricacies of Capetian and Aragonese dynastic politics. Periodic bursts of popular crusading occurred throughout the decades, spurred by events like the Mongol victory at Homs and grassroots movements in France and Germany. Despite numerous obstacles, the papacy's establishment of taxation, including a six-year tithe on clerical incomes, to fund contracted professional crusading armies, represented a remarkable feat of institutionalisation.[106]

Beginning in 1304 and lasting the entire 14th century, the Teutonic Order used the privileges Innocent IV had granted in 1245 to recruit crusaders in Prussia and Livonia, in the absence of any formal crusade authority. Knightly volunteers from every Catholic state in western Europe flocked to take part in campaigns known as Reisen, or journeys, as part of a chivalric cult.[107] Commencing in 1332, the numerous Holy Leagues in the form of temporary alliances between interested Christian powers, were a new manifestation of the movement. Successful campaigns included the capture of Smyrna in 1344, the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and the recovery of territory in the Balkans between 1684 and 1697.[108]

After the Treaty of Brétigny between England and France, the anarchic political situation in Italy prompted the curia to begin issuing indulgences for those who would fight the merceneries threatening the pope and his court at Avignon. In 1378, the Western Schism split the papacy into two and then three, with rival Popes declaring crusades against each other. The growing threat from the Ottoman Turks provided a welcome distraction that would unite the papacy and divert the violence to another front.[109] By the end of the century, the Teutonic Order's Reisen had become obsolescent. Commoners had limited interaction with crusading beyond the preaching of indulgences, the success of which depended on the preacher's ability, local powers' attitudes, and the extent of promotion. However, there is no evidence that the failure to organize anti-Turkish crusading was due to popular apathy or hostility rather than to finance and politics.[110]

15th century[edit]

Eugenius IV became Pope in 1431 and entered into ecumenical negotiation with the Byzantine Empire. John V Palaiologos's discussions with Eugenius led to an announcement of unification of the Latin, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Nestorian, and Cypriot Maronite churches. In return the Byzantines received military assistance. Between 1440 and 1444, Eugenius coordinated efforts to defend Constantinople from the Turks. However, this strategy failed in a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Varna in November 1444. The fall of Constantinople to Mehmed II in 1453 marked the beginning of a twenty-eight-year expansion of the sultanate.[111]

Pius II suggested to Mehmed II the possibility of converting to Christianity and emulating the legacy of Constantine. Despite coming close to organizing an anti-Turkish crusade in 1464, his plans ultimately failed. Throughout his papacy and those of his immediate successors, the raised funds and military resources were insufficient, poorly timed, or misallocated for effective action against the Turks. This was despite:

- the commissioning of advisory tracts reconsidering the political, financial, and military issues;

- Frankish rulers exiled from the Holy Land who toured Christendom's courts seeking assistance;

- individuals, such as Cardinal Bessarion, dedicating themselves to the crusading movement; and

- the continued levying of church taxes and preaching of indulgences.[112]

Warfare was now more professional and costly.[110] This was driven by factors including contractual recruitment, increased intelligence and espionage, a greater emphasis on naval warfare, the grooming of alliances, new and varied tactics to deal with different circumstances and opposition, and the hiring of experts in siege warfare.[113] There was disillusionment and suspicion of how practical the objectives of the movements were. Lay sovereigns were more independent and prioritized their own objectives. The political authority of the papacy was reduced by the Western Schism, so popes such as Pius II and Innocent VIII found their congresses ignored. Politics and self-interest wrecked any plans. All of Europe acknowledged the need for a crusade to combat the Ottoman Empire, but effectively all blocked its formation. Popular feeling is difficult to judge: actual crusading had long since become distant from most commoners' lives. One example from 1488 saw Wageningen parishioners influenced by their priest's criticism of crusading to such a degree they refused to allow the collectors to take away donations. This contrasts with chronicle accounts of successful preaching in Erfurt at the same time and the extraordinary response for a crusade to relieve Belgrade in 1456.[110]

Around the end of the 15th century, the military orders were transformed. Castile nationalized its orders between 1487 and 1499. In 1523, the Hospitallers retreated from Rhodes to Crete and Sicily and in 1530 to Malta and Gozo. The State of the Teutonic Order became the hereditary Duchy of Prussia when the last Prussian master, Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, converted to Lutheranism and became the first duke under oath to his uncle the Polish king.[114]

16th century[edit]

In the 16th century, the rivalry between Catholic monarchs prevented anti-Protestant crusades, but individual military actions were rewarded with crusader privileges, including Irish Catholic rebellions against English Protestant rule and the Spanish Armada's attack on England under Queen Elizabeth I.[115] In 1562, Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, became the hereditary Grand Master of the Order of Saint Stephen, a Tuscan military order he founded, which was modelled on the knights of Malta.[116] The Hospitallers remained the only independent military order with a positive strategy. Other orders continued as aristocratic corporations while lay powers absorbed local orders, outposts, and priories.[117]

17th century and later[edit]

Crusading continued in the 17th century, mainly associated with the Hapsburgs and the Spanish national identity. Crusade indulgences and taxation were used in support of the Cretan War (1645–1669), the Battle of Vienna, and the Holy League (1684). Although the Hospitallers continued the military orders in the 18th century, the crusading movement soon ended in terms of acquiescence, popularity, and support.[118]

The French Revolution resulted in widespread confiscations from the military orders, which were now largely irrelevant, apart from minor effects in the Hapsburg Empire.[117] The Hospitallers continued acting as a military order from its territory in Malta until the island was conquered by Napoleon in 1798.[108][119] In 1809, Napoleon went on to suppress the Order of St Stephen, and the Teutonic Order was stripped of its German possessions before relocating to Vienna. At this point, its identity as a military order ended.[116]

In 1936, the Catholic church in Spain supported the coup of Francisco Franco, declaring a crusade against Marxism and atheism. Thirty-six years of National Catholicism followed, during which the idea of Reconquista as a foundation of historical memory, celebration, and Spanish national identity became entrenched in conservative circles. Reconquista lost its historiographical hegemony when Spain restored democracy in 1978, but it remains a fundamental definition of the medieval period within conservative sectors of academia, politics, and the media because of its strong ideological connotations.[120]

Legacy[edit]

The crusading movement left an enduring legacy, defining western culture in the late medieval period and leaving an historical impact on the Islamic world. The impact touched every aspect of European life.[121]

Historians have debated whether the Latin States created by the movement in the Eastern Europe were the first examples of European colonialism. The Outremer is the name that is often used for these states. This translates as a Europe Overseas.[44][122] In mid-19th century historiography this became a focus for European nationalism and associated with European colonialism.[123][124] This is a view that was contested. The Latin settlements did not easily fit to the model of a colony. They were neither directly controlled or exploited by a homeland. Historians have used the idea of a religious colony in order to accommodate these discrepancies in their colonial theories. A different definition covers a territory conquered and settled with religious motivation. This territory maintains close contact with its homeland, share the same religious views and requires support in both military and financial terms. Venetian Greece carved out of the Byzantine Empire as a result of the crusading movement following the Fourth Crusade offers a better match to the traditional model of colonialism. Venice had a political and economic stake in these territories. Indeed, this was to such a degree that the region attracted settlers that would otherwise migrated to the Latin East. It this way its success actually weakened the crusader states.[125]

The crusading movement created a flourishing system of trade in the Mediterranean. New routes were created to serve the Outremer with Genoa and Venice planting profitable trading outposts across the region. [126] Many historians argue that the increasingly frequent contact between the Latin Christian and Islamic cultures was a positive. It was foundational in the progress of European civilisation and the Renaissance.[127] Closer contact with the Muslim and Byzantine worlds enabled access for western European scholars to classical Greek and Roman texts. This led to the rediscovery by pre-Christian philosophy, science, and medicine.[128] It is difficult to identify exactly the source of cultural interchange. The increase of knowledge of Islamic culture was the result of contact that stretched the breadth of the Mediterranean Sea.[129]

The movement enabled the papacy to consolidate its leadership of the Latin church. The clergy became inured to violence, while the church developed closer links with feudalism and military capability.[44] The Medieval Inquisition, Dominican and military orders as were all institutionalised.[130] A catalyst for the Reformation was the growing opposition to developments in the use of indulgences.[131] Relations between western Christians, the Greeks and the Muslims were also soured by the behaviour of the crusaders. These differences became an enduring barrier between the Latin, the Orthodox and Islamic worlds. The crusading movement had a reputation of a defeated aggressor and unification of the Christian churches became problematic.[44] Political Islam makes historical parallels, provoking paradigms of jihad and struggle. Arab nationalism looks on the movement as an example of Western imperialism.[132] Thinkers, politicians, and historians in the Islamic world draw an equivalence with more recent events like the League of Nations mandates to govern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.[133] An opposing analogy has developed in Western world right-wing circles. Here, Christianity is considered to be under an similar existential Islamic religious and demographic threat. The result is anti-Islamic rhetoric and symbols. This provides an argument for a contest with a religious foe.[134] Thomas F. Madden argues that these modern tensions are the result of constructed view developed during the 19th century by the colonial powers. This in turn led to the rise of Arab nationalism. For Madden, the crusading movement is a defensive and solely medieval phenomenon.[135]

Historiography[edit]

Almost immediately, the First Crusade provoked literary examination. Initially this served as propaganda for the crusading movement and was based on a few separate but related works. One of these, Gesta Francorum literally translates as the deeds of the Franks. It created a template for later works based on papal, northern French, and Benedictine ideas. It considered military success or failure entirely to God's will in its promotion of violent action.[136]

Albert of Aachen produced contrasting vernacular stories of adventure.[137] At this point the early chroniclers concentrated on the moral lessons that could be taken from the crusades. This reinforced normative moral and cultural positions.[138] Academic crusade historian Paul Chevedden argued that the early accounts were already an anachronism. The writers were writing with the knowledge of the unexpected success of the First Crusade. For Chevedden, more can be learned about how the crusading movement was viewed in the 11th century in the works of Urban II who died ignorant of the crusade's success.[139] Albert's adventure stories were developed and extended in turn by William of Tyre before the end of the 12th century.[137] William documented the early history of the military Crusader States. In this he illustrated the tension between secular and providential motivation.[137]

In the 16th century the Reformation and the Ottoman expansion shaped opinion. Protestant martyrologist John Foxe writing in his 1566 work History of the Turks blamed the sins of the Catholic Church for the failure of the crusades. He also criticised the use of crusading against those he considered had maintained the faith, such as the Albigensians and Waldensians. The Lutheran scholar Matthew Dresser (1536–1607) went further. He praised for their faith, but considered that Urban II was motivated by his conflict with Emperor Henry IV. Dresser considered that the flaw in the crusading movement was that the idea of restoring the physical holy places was "detestable superstition".[140] One of the first to number the crusades was the French Catholic lawyer Étienne Pasquier. His suggestion was that there were six. In his work he highlighted the failures. In addition he raised the damage that religious conflict had inflicted on France and the church. The key points were the victims of papal aggression, the sale of indulgences, abuses in the church, corruption, and conflicts at home.[141]

Age of Enlightenment philosopher-historians such as David Hume, Voltaire and Edward Gibbon used crusading as a conceptual tool to critique religion, civilisation and cultural mores. For them the positives effects of crusading, such as the increasing liberty that municipalities were able to purchase from feudal lords, were only by-products. This view was then criticised in the 19th century by crusade enthusiasts as being unnecessarily hostile to, and ignorant of, the crusades.[142] Alternatively, Claude Fleury and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz proposed that the crusades were one stage in the improvement of European civilisation; that paradigm was further developed by the Rationalists.[143]

The idea that the crusades were an important part of national history and identity continued to evolve. In scholarly literature, the term "holy war" was replaced by the neutral German kreuzzug and French croisade.[144] Gibbon followed Thomas Fuller in dismissing the concept that the crusades were a legitimate defence, as they were disproportionate to the threat presented; Palestine was an objective, not because of reason but because of fanaticism and superstition.[145] William Robertson expanded on Fleury in a new, empirical, objective approach, placing crusading in a narrative of progress towards modernity. The cultural consequences of growth in trade, the rise of the Italian cities and progress are elaborated in his work. In this he influenced his student Walter Scott.[146] Much of the popular understanding of the crusades derives from the 19th century novels of Scott and the French histories by Joseph François Michaud.[147] Michaud's viewpoint provoked Muslim attitudes. Previously, the crusading movement had aroused little interest among Islamic and Arabic scholars. This changed with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the penetration of European power into the Eastern Mediterrarean.[132]

In a 2001 article—"The Historiography of the Crusades"—Giles Constable attempted to categorise what is meant by "Crusade" into four areas of contemporary crusade study. His view was that Traditionalists such as Hans Eberhard Mayer are concerned with where the crusades were aimed, Pluralists such as Jonathan Riley-Smith concentrate on how the crusades were organised, Popularists including Paul Alphandery and Etienne Delaruelle focus on the popular groundswells of religious fervour, and Generalists, such as Ernst-Dieter Hehl focus on the phenomenon of Latin holy wars.[148][149] The historian Thomas F. Madden argues that modern tensions are the result of a constructed view of the crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century and transmitted into Arab nationalism. For him the crusades are a medieval phenomenon in which the crusaders were engaged in a defensive war on behalf of their co-religionists.[135]

The Byzantines harboured a negative perspective on holy warfare, failing to grasp the concept of the Crusades and finding them repugnant. Although some initially embraced Westerners due to a common Christianity, their trust soon waned. With a pragmatic approach, the Byzantines prioritised strategic locations such as Antioch over sentimental objectives like Jerusalem. They couldn't comprehend the merging of pilgrimage and warfare. The advocacy for infidel eradication by St. Bernard and the militant role of the Templars would deeply shock them. Suspicions arose among the Byzantines that Westerners aimed for imperial conquest, leading to growing animosity. Despite occasionally using the term "holy war" in historical contexts, Byzantine conflicts were not inherently holy but perceived as just, defending the empire and Christian faith. War, to the Byzantines, was justified solely for the defence of the empire, in contrast to Muslim expansionist ideals and Western knights' notion of holy warfare to glorify Christianity.[150]

Scholars like Carole Hillenbrand assert that within the broader context of Muslim historical events, the Crusades were considered a marginal issue when compared to the collapse of the Caliphate, the Mongol invasions, and the rise of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, supplanting Arab rule.[151] Arab historians, influenced by historical opposition to Turkish control over their homelands, adopted a Western perspective on the Crusades.[151] Syrian Christians proficient in Arabic played a vital role by translating French histories into Arabic. The first modern biography of Saladin was authored by the Ottoman Turk Namık Kemal in 1872, while the Egyptian Sayyid Ali al-Hariri produced the initial Arabic history of the Crusades in response to Kaiser Wilhelm II's visit to Jerusalem in 1898.[152] The visit triggered a renewed interest in Saladin, who had previously been overshadowed by more recent leaders like Baybars. The reinterpretation of Saladin as a hero against Western imperialism gained traction among nationalist Arabs, fueled by anti-imperialist sentiment.[153] The intersection of history and contemporary politics is evident in the development of ideas surrounding jihad and Arab nationalism. Historical parallels between the Crusades and modern political events, such as the establishment of Israel in 1948, have been drawn.[133] In contemporary Western discourse, right-wing perspectives have emerged, viewing Christianity as under threat analogous to the Crusades, using crusader symbols and anti-Islamic rhetoric for propaganda purposes.[134] Madden argues that Arab nationalism absorbed a constructed view of the Crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century, contributing to modern tensions. Madden suggests that the crusading movement, from a medieval perspective, engaged in a defensive war on behalf of co-religionists.[135]

See also[edit]

- History of the Jews and the Crusades

- List of principal crusaders

- List of Crusader castles

- Women in the Crusades

- Criticism of crusading

References[edit]

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. xxiii.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Riley-Smith 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bull 1995, p. 26.

- ^ Morris 1989, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Barber 2012, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 80.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 82.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 144.

- ^ Latham 2011, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Latham 2012, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyerman 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 123.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, p. 80.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Riley-Smith 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyerman 2019, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 524–525.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 533–535.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyerman 2019, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 919.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyerman 2019, pp. 14–16, 338, 359.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 98.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 14.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Madden 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Morris 1989, pp. 150, 335.

- ^ Bull 1995, p. 22.

- ^ Lloyd 1995, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Honig 2001, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Morris 1989, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 50, 64.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, p. 84.

- ^ Prawer 2001, p. 252.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Davies 1997, p. 359.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Riley-Smith 1995, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Bull 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Lloyd 1995, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Morris 1989, pp. 458, 495.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 263.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. xxv.

- ^ Dickson 2008, p. xiii.

- ^ Dickson 2008, pp. 9–14.

- ^ Dickson 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Routledge 1995, p. 93

- ^ Jubb 2005, pp. 227–229.

- ^ Jubb 2005, p. 232.

- ^ Jubb 2005, p. 226.

- ^ Jubb 2005, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 97.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 147.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 65, 69-70.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 14, 21.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 118.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 36.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyerman 2019, p. 293.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 335.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, p. 87.

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Routledge 1995, p. 111.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 478.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Buck 2020, p. 298.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 408.

- ^ Dickson 2008, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Madden 2013, p. 155.

- ^ Housley 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Mannion 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 330.

- ^ Richard 2005, p. 207.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 46.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 336.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 258–260.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Dickson 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Dickson 2008, p. 101-102.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 223.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 620.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 648.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, p. 211.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 352.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 247.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 28.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 314.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Housley 1995, p. 260.

- ^ Forey 1995, p. 211.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 399–401.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 57.

- ^ Housley 1995, pp. 262–265.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 275.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Riley-Smith 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 270.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Housley 1995, p. 281.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 279.

- ^ Housley 1995, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 264.

- ^ Luttrell 1995, pp. 348.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luttrell 1995, p. 352.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luttrell 1995, p. 364.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 293.

- ^ Luttrell 1995, p. 360.

- ^ García-Sanjuán 2018, p. 4

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, pp. 4–5, 36.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 282.

- ^ Madden 2013, p. 227.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Phillips 1995, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Housley 2006, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Nicholson 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Nicholson 2004, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 667–668.

- ^ Strayer 1992, p. 143.

- ^ Housley 2006, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 675–680.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 674–675.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Koch 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Madden 2013, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tyerman 2011, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Chevedden 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 38–42.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 79.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 71.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 80–86.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 448–449, 454.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Constable 2001, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Dennis 2001, pp. 31–40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hillenbrand 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 675–677.

- ^ Riley-Smith 2009, pp. 6–66.

Bibliography[edit]

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Two Cities: Medieval Europe 1050-1320. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17414-7.

- Buck, Andrew D. (2020). "Settlement, Identity, and Memory in the Latin East: An Examination of the Term 'Crusader States'". The English Historical Review. 135 (573): 271–302. doi:10.1093/ehr/ceaa008.

- Bull, Marcus (1995). "Origins". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 13–33. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Chevedden, Paul E. (2013). "Crusade Creationism "versus" Pope Urban Ii's Conceptualization of the Crusades". The Historian. 75 (1). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 1–46. doi:10.1111/hisn.12000. JSTOR 24455961. S2CID 142787038. Archived from the original on 2022-04-05. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Constable, Giles (2001). "The Historiography of the Crusades". In Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy P. Mottahedeh (ed.). The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-88402-277-0.

- Davies, Norman (1997). Europe: A History. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6633-6.

- Dennis, Gorge T. (2001). "Defenders of the Christian People:Holy War in Byzantium". In Laiou, Angeliki E.; Parviz Mottahedeh, Roy (eds.). The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World (PDF). Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 31–40. ISBN 0-88402-277-3.

- Dickson, Gary (2008). The Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-9989-4.

- Forey, Alan (1995). "The Military Orders 1120-1312". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 184–217. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- García-Sanjuán, Alejandro (2018). "Rejecting al-Andalus, exalting the Reconquista: historical memory in contemporary Spain". Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies. 10 (1): 127–145. doi:10.1080/17546559.2016.1268263. S2CID 157964339.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (1999). The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0630-6.

- Honig, Jan Willem (2001). "Warfare in the Middle Ages". In Hartmann, Anja V.; Hauser, Beatrice (eds.). War, Peace and World Orders in European History. Routledge. pp. 113–126. ISBN 978-0-415-24440-4.

- Housley, Norman (1995). "The Crusading Movement 1271-1700". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 260–294. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Housley, Norman (2002). Religious Warfare in Europe, 1400-1536. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820811-1.

- Housley, Norman (2006). Contesting the Crusades. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1189-8.

- Jotischky, Andrew (2004). Crusading and the Crusader States (1st ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-41851-6.

- Jubb, M. (2005). "The Crusaders' Perceptions of their Opponents". In Nicholson, Helen J. (ed.). Palgrave Advances in the Crusades. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 225–244. ISBN 978-1-4039-1237-4.

- Koch, Ariel (2017). "The New Crusaders: Contemporary Extreme Right Symbolism and Rhetoric". Perspectives on Terrorism. 11 (5): 13–24. ISSN 2334-3745. Archived from the original on 2021-03-24. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Latham, Andrew A. (2011). "Theorizing the Crusades: Identity, Institutions, and Religious War in Medieval Latin Christendom". International Studies Quarterly. 55 (1): 223–243. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00642.x. JSTOR 23019520.

- Latham, Andrew A. (2012). Theorizing Medieval Geopolitics - War and World Order in the Age of the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87184-6.

- Lloyd, Simon (1995). "The Crusading Movement 1095-1274". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 34–64. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Luttrell, Anthony (1995). "The Military Orders, 1312–1798". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 326–364. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2013). The Concise History of the Crusades (Third ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-1576-4.

- Mannion, Lee (2014). Narrating the Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05781-4.

- Morris, Colin (1989). The Papal Monarchy - The Western Church from 1050 to 1250. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826925-0. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- Nicholson, Helen (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32685-1.

- Phillips, Jonathan (1995). "The Latin East, 1098-1291". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 112–140. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Prawer, Joshua (2001). The Crusaders' Kingdom. Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-84212-224-2.

- Richard, Jean (2005). "National feeling and the lagacy of the crusade". In Nicholson, Helen J. (ed.). Palgrave Advances in the Crusades. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 204–224. ISBN 978-1-4039-1237-4.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1995). "The Crusading Movement and Historians". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1995b). "The State of Mind of the Crusaders to the East". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 66–90. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2009). What Were the Crusades?. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-22069-0.

- Routledge, Michael (1995). "Songs". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–110. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Strayer, Joseph Reese (1992). The Albigensian Crusades. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06476-2.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2011). The Debate on the Crusades, 1099–2010. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7320-5. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2019). The World of the Crusades. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21739-1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

Further reading[edit]

- Cobb, Paul M. (2014). The Race for Paradise : an Islamic History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press.

- Flori, Jean (2005). "Ideology and Motivations in the First Crusade". In Nicholson, Helen J. (ed.). Palgrave Advances in the Crusades. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 15–36. doi:10.1057/9780230524095_2. ISBN 978-1-4039-1237-4.

- Horowitz, Michael C. (2009). "Long Time Going:Religion and the Duration of Crusading". International Security. 34 (27). MIT Press: 162–193. doi:10.1162/isec.2009.34.2.162. JSTOR 40389216. S2CID 57564747. Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- Kedar, Benjamin Z. (1998). "Crusade Historians and the Massacres of 1096". Jewish History. 12 (2): 11–31. doi:10.1007/BF02335496. S2CID 153734729.

- Kostick, Conor (2008). The Social Structure of the First Crusade. Brill.

- Maier, C. (2000). Crusade Propaganda and Ideology: Model Sermons for the Preaching of the Cross. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511496554. ISBN 978-0-521-59061-7.

- Polk, William R. (2018). Crusade and Jihad: The Thousand-Year War Between the Muslim World and the Global North. Yale University Press.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2001). "The crusading movement". In Hartmann, Anja V.; Hauser, Beatrice (eds.). War, Peace and World Orders in European History. Routledge. pp. 127–140. ISBN 978-0-415-24440-4.

- Tuck, Richard (1999). The Rights of War and Peace: Political Thought and the International Order from Grotius to Kant. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820753-5.

- Tyerman, Christopher (1995). "Were There Any Crusades in the Twelfth Century?". The English Historical Review. 110 (437). Oxford University Press: 553–577. doi:10.1093/ehr/CX.437.553. JSTOR 578335.