Yerkes Observatory

| |||||||||||||||

| Alternative names | 754 YE | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Named after | Charles Yerkes | ||||||||||||||

| Observatory code | 754 | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Williams Bay, Walworth County, Wisconsin | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 42°34′13″N 88°33′24″W / 42.5703°N 88.5567°W | ||||||||||||||

| Altitude | 334 m (1,096 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1892[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Website | yerkesobservatory.org | ||||||||||||||

| Telescopes | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

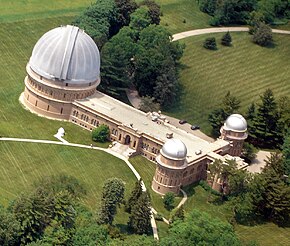

Yerkes Observatory (/ˈjɜːrkiːz/ YUR-keez) is an astronomical observatory located in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, United States. The observatory was operated by the University of Chicago Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics[2][3] from its founding in 1897 until 2018. Ownership was transferred to the non-profit Yerkes Future Foundation (YFF) in May 2020, which began millions of dollars of restoration and renovation of the historic building and grounds. Yerkes re-opened for public tours and programming in May, 2022.[4] The April, 2024 issue of National Geographic magazine (both print and online) featured a story about the Observatory and ongoing work to restore it to relevance for astronomy, public science engagement and exploring big ideas through art, science, culture and landscape. The observatory offers tickets to programs and tours on its website.

The observatory, often called "the birthplace of modern astrophysics," was founded in 1892 by astronomer George Ellery Hale and financed by businessman Charles T. Yerkes. It represented a shift in the thinking about observatories, from their being mere housing for telescopes and observers, to the early-20th-century concept of observation equipment integrated with laboratory space for physics and chemistry analysis.

The observatory's main dome houses a 40 in-diameter (102 cm) doublet lens refracting telescope, the second-largest refractor ever successfully used for astronomy. The largest lens is the Swedish 1-m Solar Telescope. There are several smaller telescopes – some permanently mounted – that are primarily used for educational purposes. The observatory also holds a collection of over 170,000 photographic plates.[5]

The Yerkes 40-inch was the largest refracting-type telescope in the world when it was dedicated in 1897. During this time, there were many questions about the merits of the various materials used to construct and design telescopes. Another large telescope of this period was the Great Melbourne Telescope, which was a reflector. In the United States, the Lick refractor had just a few years earlier come online in 1888 in California with a 91 cm lens.

Prior to its installation, the telescope on its enormous German equatorial mount was shown at the World's Columbian Exhibition in Chicago during the time the observatory was under construction.

The observatory was a center for serious astronomical research for more than 100 years. By the 21st century, however, the historic telescope had reached the end of its research life. The University of Chicago closed the observatory in October 2018. In November 2019, it was announced that the university would transfer Yerkes Observatory to the non-profit Yerkes Future Foundation (YFF). The transfer of ownership took place on May 1, 2020.[6] The community-based foundation hired a director and launched a $25M campaign to restore the observatory and the fifty acres of historic Olmsted-designed grounds. By 2024 the foundation had already raised some $21million towards its goal, and extended the goal to $40million. The mission of Yerkes is to "...advance humankind's understanding of the universe and our place within it, igniting curiosity, facilitating exploration, and nurturing a deep sense of connection with our environment, our planet and each other."[7] The foundation has taken steps to transform the observatory and its grounds into a unique public site for astronomy and discovery, hosting researchers and graduate students in astronomy, offering public talks and programs, tours and education programs. In 2023 Yerkes opened four newly-built miles of walking trails and installed the first commissioned outdoor sculpture by artist Ashley Zelinskie. Yerkes has hosted talks, programs or residencies with Grammy-winning musicians and composers Eighth Blackbird, Brooklyn-based artist Ashley Zelinskie, former US Poet Laureate Tracy K Smith, astronomer and public educator Dean Regas, and former Senior Scientist of the James Webb Space Telescope and Nobel prizewinner Dr. John Mather. Major restoration work has been ongoing and will continue for many years ahead. Since the observatory re-opened to the public in summer 2022 for tours and programs, more than 50,000 ticketed visitors have taken tours or attended events, with tens of thousands more enjoying the open-access landscape.

Telescopes[edit]

In the 1860s Chicago became home of the largest telescope in America, the Dearborn 18+1⁄2 in (47 cm) refractor.[8] It was later surpassed by the U.S. Naval Observatory's 26 inch, which would go on to discover the moons of Mars in 1877. There was an extraordinary increase of larger telescopes in finely furnished observatories in the late 1800s. In the 1890s various forces came together to establish an observatory of art, science, and superlative instruments in Williams Bay, Wisconsin.

The telescope was surpassed by the Harvard College Observatory, 60 in (152 cm) reflector less than ten years later, although it remained a center for research for decades afterwards. In addition to the large refractor, Yerkes also conducted a great amount of Solar observations.

Background[edit]

Yerkes Observatory's 40-inch (102 cm) refracting telescope has a doublet lens produced by the optical firm Alvan Clark & Sons and a mounting by the Warner & Swasey Company. It was the largest refracting telescope used for astronomical research.[9][10] In the years following its establishment, the bar was set and tried to be exceeded; an even larger demonstration refractor, the Great Paris Exhibition Telescope of 1900, was exhibited at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1900.[10]

However, this was not much of a success, was dismantled, and did not become part of an active University observatory. The mounting and tube for the 40-inch telescope was exhibited at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago before being installed in the observatory. The grinding of the lens was completed later.[11]

40-inch aperture refractor[edit]

The glass blanks for what would become Yerkes Great Refractor were made in Paris, France by Mantois and delivered to Alvan Clark & Sons in Massachusetts where they were completed.[12] Clark then made what would be the largest telescope lens ever crafted and this was mounted to an Equatorial mount made by Warner & Swasey for the observatory.[12] The telescope had an aperture of 40 inches (~102 cm) and focal length of 19.3 meters, giving it a focal ratio of f/19.[12]

The lens, an achromatic doublet which has two sections to reduce chromatic aberration, weighed 225 kilograms, and was the last big lens made by Clark before he died in 1897.[12] Glass lens telescopes had a good reputation compared to speculum metal and silver on glass mirror telescopes, which had not quite proven themselves in the 1890s. For example, the Leviathan of Parsonstown was a 1.8 meter telescope with a speculum metal mirror, but getting good astronomical results from this technology could be difficult. Another large telescope of this period was the Great Melbourne Telescope in Australia, also a metal mirror telescope.

Some of the instruments for the 40-inch refractor (circa 1890s) were:[13]

- Filar Micrometer

- Solar spectrograph

- Spectroheliograph

- Stellar spectrograph

- Photoheliograph

The 40-inch refractor was modernized in the late 1960s with electronics of the period.[14] The telescope was painted, the manual controls were removed, and electric operations were added at that time.[14] This included nixie tube displays for its operation.[14]

41-inch reflector[edit]

In the late 1960s a 40-inch reflecting telescope was added.[15][16] The 41 inch was finished by 1968, with overall installation completed by December 1967 and the optics in 1968.[17][18] While the telescope has a clear aperture of 40-inches, the mirror's physical diameter measures 41-inches leading to the telescope usually being called the "41 inch" to avoid confusion with the 40 inch refractor.[18][17][19] The mirror is made from low-expansion glass.[14] The glass used was CER-VII−R.[14]

The launch instruments for the 41 inch reflector included:[19]

- Image tube spectrograph

- photoelectric photometer

- photoelectric spectrophotometer

The 40-inch reflector is of the Ritchey-Chretien optical design.[20] The 41-inch helped pioneer the field of adaptive optics.[21]

Additional instruments and equipment[edit]

A 12-inch refractor was moved to Yerkes from Kenwood Observatory in the 1890s.[13] Two other telescopes planned for the observatory in the 1890s were a 12-inch aperture refractor and a 24-inch reflecting telescope.[13] There was a heliostat mirror and a meridian room for a transit instrument.[13]

A two-foot aperture reflecting telescope was manufactured at the observatory itself.[22] The clear aperture of the telescope was actually 23.5 inches.[22] The glass blanks were cast in France by Saint Gobain Glass Works, and then were figured (polished into telescopic shape) at the Yerkes Observatory.[22] The 'Two foot telescope' used a roughly seven foot long skeleton truss made of aluminum.[23]

At one point the Observatory had an IBM 1620 computer, which it used for three years.[14] This was replaced with an IBM 1130 computer in the 1960s.[14]

A Microphotometer was built by Gaertner Scientific Corporation, which was delivered in February 1968 to the observatory.[24][25]

Later, there was another 24-inch reflecting telescope by Boller & Chivens.[15][26] This was contracted in the early 1960s under direction of observatory director W. Albert Hiltner.[27] This telescope was installed in one of the smaller Yerkes domes, and it is known to have been used for visitor programs.[28] This was a design by Boller & Chivens with Cassegrain optical setup, with a 24-inch (61 cm) clear aperture and is on an off-axis equatorial mount.[29]

A 7-inch (18 cm) diameter aperture Schmidt camera was also at Yerkes Observatory.[30]

The Snow Solar Telescope was first established at Yerkes Observatory, and then later moved in 1904 to California.[31] A major difficulty of these telescopes was dealing with heat from the Sun, and it was built horizontally, but led to a vertical solar tower design afterwards.[31] Solar tower telescopes would be a popular style for solar observatories in the 20th century, and are still used in the 21st century to observe the Sun.

Another instrument was the Bruce photographic telescope.[32] The telescope had two objective lens for photography, one doublet of 10 inches aperture and another of 6.5 inches; in addition there is a 5-inch guide scope for visual viewing.[32] The telescope was constructed from funds donated in 1897.[32] The telescope was mounted on custom designed equatorial, the result of collaboration between Yerkes and Warner & Swasey, especially designed to offer an uninterrupted tracking for long image exposures.[32] The images were taken on glass plates about a foot on each side.[33]

The Bruce astrograph lenses were made by Brashear with Mantois of Paris glass blanks, and the lenses were completed by the year 1900.[32] The overall telescope was not completed until 1904, where it was installed in its own dome at Yerkes.[33]

The astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard's work with the Bruce telescope, with his niece Mary R. Calvert who worked as his assistant and computer, lead to the publication of a sky atlas using images taken with the instrument, and also a catalog of dark nebulae known as the Barnard catalog.[34]

Dedication[edit]

The Observatory was dedicated on October 21, 1897, and there was a large party with university, astronomers, and scientists.[35]

Before the dedication a conference of astronomers and astrophysicists was hosted at Yerkes Observatory, and took place on October 18–20, 1897.[36] This is noted as a precursor to the founding of the American Astronomical Society.

Although dedicated in 1897, it was founded in 1892.[13] Also, astronomical observations had started in the summer of 1897 before the dedication.[37]

Research and observations[edit]

Research conducted at Yerkes in the last decade[when?] includes work on the interstellar medium, globular cluster formation, infrared astronomy, and near-Earth objects. Until recently the University of Chicago also maintained an engineering center in the observatory, dedicated to building and maintaining scientific instruments. In 2012 the engineers completed work on the High-resolution Airborne Wideband Camera (HAWC), part of the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).[38] Researchers also use the Yerkes collection of over 170,000 archival photographic plates that date to the 1890s.[39] The past few years have seen astronomical research largely replaced by educational outreach and astronomical tourism activities.

In June 1967, Yerkes Observatory hosted the to-date largest meeting of the American Astronomical Society, with talks on over 200 papers.[14]

The Yerkes spectral classification (aka MKK system) was a system of stellar spectral classification introduced in 1943 by William Wilson Morgan, Philip C. Keenan, and Edith Kellman from Yerkes Observatory.[40] This two-dimensional (temperature and luminosity) classification scheme is based on spectral lines sensitive to stellar temperature and surface gravity, which are related to luminosity (the Harvard classification is based on surface temperature). Later, in 1953, after some revisions of lists of standard stars and classification criteria, the scheme was named the Morgan–Keenan classification, or MK.[41]

Research work of the Yerkes Observatory has been cited over 10,000 times.[42]

In 1899, observations of Neptune's moon Triton were published, with data recorded using the Warner & Swasey micrometer.[43] In 1898 and 1899, Neptune was at opposition.[43]

In 1906, a star catalog of over 13,600 stars was published.[44] Also, there was some important work on Solar research in the early years, which was of interest to Hale.[44] He went on to the Snow Solar Telescope at Mount Wilson in California.[31] This was first operated at Yerkes and then moved to California.[31]

An example of an asteroid discovered at Yerkes is 1024 Hale, provisional designation A923 YO13, a carbonaceous background asteroid from the outer regions of the asteroid belt, approximately 45 km (28 mi) in diameter. The asteroid was discovered on 2 December 1923 by Belgian–American astronomer George Van Biesbroeck at Yerkes Observatory, and it was named for astronomer George Ellery Hale of Yerkes Observatory fame. Some additional examples include 990 Yerkes, 991 McDonalda, and 992 Swasey around this time; many more minor planets would be discovered at the observatory in the following decades.

Notable staff and visitors[edit]

Notable astronomers who conducted research at Yerkes include Albert Michelson,[45] Edwin Hubble (who did his graduate work at Yerkes and for whom the Hubble Space Telescope was named), Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (for whom the Chandra Space Telescope was named), Ukrainian-American astronomer Otto Struve,[3] Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper (noted for theorizing the Kuiper belt, home to dwarf planet Pluto), Nancy Grace Roman, NASA's first Chief of Astronomy (who did her graduate work at Yerkes), and the twentieth-century popularizer of astronomy Carl Sagan. In 2022 astronomer Dr. Amanda Bauer was the first astronomer hired by the Yerkes Future Foundation, which took over the observatory, its restoration and operation from the University of Chicago in 2020. She came to Yerkes from the Vera Rubin Telescope, then under construction in Chile, and was appointed the first-ever Montgomery Foundation Deputy Director and Head of Science and Education.

Visitors:

- Albert Einstein (May, 1921)

- Dr. John Mather, senior astrophysicist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Nobel laureate in Physics (2023)

- Hillary Rodham Clinton, former U.S. Secretary of State (2022)

- Grace Stanke, Miss America 2022, nuclear engineering student (2022)

- Tracy K Smith, Pulitzer prize-winner, author, former US Poet Laureate (2023)

- Kate Rubins, astronaut and first human to sequence DNA in space (2023)

- Dr. Edward (Ed) Lu, astronaut (2024)

Directors of Yerkes Observatory:[46]

- 2021–curr – Dennis Kois

- 2012–2018 – Doyal Al Harper (2nd time)

- 2001–2012 – Kyle M. Cudworth

- 1989–2001 – Richard G. Kron

- 1982–1989 – Doyal Al Harper

- 1974–1982 – Lewis M. Hobbs

- 1972–1974 – William Van Altena

- 1966–1972 – Charles Robert O'Dell

- 1963–1966 – William Hiltner

- 1960–1963 – William W. Morgan

- 1957–1960 – Gerard P. Kuiper (2nd time)

- 1950–1957 – Bengt Strömgren

- 1947–1950 – Gerard P. Kuiper

- 1932–1947 – Otto Struve

- 1903–1932 – Edwin B. Frost

- 1897–1903 – George Ellery Hale

The 2005 proposed development[edit]

In 2006 the University of Chicago announced plans to sell the observatory and its land to a developer. Under the plan, a 100-room resort with a large spa operation and attendant parking and support facilities was to be located on the 9-acre (36,000 m2) virgin wooded Yerkes land on the lakeshore—the last such undeveloped, natural site on Geneva Lake's 21 mi (34 km) shoreline. About 70 homes were to be developed on the upper Yerkes property surrounding the historic observatory. These grounds had been designed more than 100 years previously by John Charles Olmsted, the nephew and adopted son of famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Ultimately, Williams Bay's refusal to change the zoning from education to residential caused the developer to abandon its development plans. In view of the public controversy surrounding the development proposals, the university suspended these plans in January 2007.[47]

Closure and Transfer to the Yerkes Future Foundation[edit]

In March 2018, the University of Chicago announced that it would no longer operate the observatory after October 1, 2018, and would be seeking a new owner.[48] In May 2018, the Yerkes Future Foundation, a group of local residents, submitted an expression of interest to the University of Chicago with a proposal that would seek to maintain public access to the site and continuation of the educational programs.[49] Transfer of operation to a successor operator was not arranged by the end of August, and the facility was closed to the general public on October 1. Some research activities continued at the Observatory, including access and use of the extensive historical glass plate archives at the site. Yerkes education and outreach staff formed a nonprofit organization – GLAS – to continue their programs at another site after the closing.[50]

In May 2019, the university continued to negotiate with interested parties on Yerkes's future, primarily with the Yerkes Future Foundation. It was announced in November 2018 that a sticking point has been the need to include the Yerkes family in the discussions. Mr. Yerkes's agreement in making his donation to the university transfers ownership "To have and to hold unto the said Trustees [of the University of Chicago] and their successors so long as they shall use the same for the purpose of astronomical investigation, but upon their failure to do so, the property hereby conveyed shall revert to the said Charles T. Yerkes or his heirs at law, the same as if this conveyance had never been made."[51]

In 2022, the site was re-opened to visitors.[52]

In 2023, Amanda Bauer was interviewed and demonstrates the use of the telescope, partly restored. Full restoration was expected to take 10 more years.[53]

Gargoyle sculptures, location, and landscaping[edit]

The Observatory grounds and buildings are renowned for more than the Great Refractor, but also sculptures and architecture.[54] In addition, the landscaping is also famed for its design work by Olmsted.[55] The observatory building was designed by architect Henry Ives Cobb, and has been referred to as being in the Beaux Arts style.[56] The building is noted for its blend of styles and rich ornamentation featuring a variety of animal and mythological designs.[56]

On the building there are various carvings including Lion gargoyle designs.[57][54] There are also sculptures to represent various people that oversaw or supported construction of the telescope and the facility.[58] The location is noted for a good and pleasant location by Lake Geneva.[58] Although it does not have a high-altitude as preferred by modern observatories, it does have good weather, and was a considerable distance from the light and pollution of Chicago.[59]

In 1888, Williams Bay had a railway terminal added by Chicago & North Western Railroad; this provided access from Chicago, and is one factor that increased the site's development in the following decades.[60]

The editorial offices for The Astrophysical Journal were located at Yerkes Observatory until the 1960s.[35]

The landscape was designed by the same firm that designed New York Central park, the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, and the grounds were noted at one point for having multiple state record trees.[61] The tree plan design was developed in the 1910s under design from the Olmsted firm and with support of the observatory Director; the grounds included the following types of trees at that time: white fir, yellowwood tree, golden rain tree, European beech, fernleaf beech, Japanese pagoda tree, littleleaf linden, Kentucky coffeetree, ginkgo, buckthorn, cut-leaf beeches, and chestnut trees.[61]

The original landscape plan was not completed by the 1897 dedication, and there was grading and construction of gravel roads under direction of the Olmsted design as late as 1908.[62][63]

Contemporaries on debut of the Great Yerkes Refractor[edit]

Legend

A major contemporary for the Yerkes was the well-regarded 36-inch Lick refractor near San Jose, California.[64] The Yerkes, although just 4 inches in aperture larger, meant an increase of 23% in light-gathering ability.[64] Both telescopes had achromatic doublets by Alvan Clark.

The 19th century saw a transition in large telescope construction from refractor type to reflector type, with metal-film-coated glass mirrors tending to be used instead of difficult, older-style metal mirrors. The Yerkes was perhaps the greatest of the great refractors, the largest astronomical instrument in the traditional style of the 19th century refractor-based observatories.

The Yerkes was not only the largest refractor, but was tied for being the largest telescope in the world with Paris Observatory reflector (48 inch, 122 cm) when it became operational in 1896.[65]

| Name/Observatory | Aperture cm (in) |

Type | Location | Extant or Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leviathan of Parsonstown | 183 cm (72") | reflector – metal | Birr Castle; Ireland |

1845–1908* |

| Great Melbourne Telescope[66] | 122 cm (48") | reflector – metal | Melbourne Observatory, Australia | 1878 |

| National Observatory, Paris | 120 cm (47") | reflector – glass | Paris, France | 1875–1943[65] |

| Yerkes Observatory[67] | 102 cm (40") | achromat | Williams Bay, Wisconsin, USA | 1897 |

| Meudon Observatory 1m[68] | 100 cm (39.4") | reflector-glass | Meudon Observatory/ Paris Observatory | 1891 [69] |

| James Lick telescope, Lick Observatory | 91 cm (36") | achromat | Mount Hamilton, California, U.S. | 1888 |

| Crossley Reflector[70] (Lick Observatory) | 91.4 cm (36") | reflector – glass | Mount Hamilton, California, USA | 1896 |

*Note the Leviathan of Parsonstown was not used after 1890

Understanding atmosphere and trends of telescope building of the late 19th century puts the choice of a large refactor in perspective. Although there were some very large reflectors, the speculum mirrors they relied on reflected about 2/3 of the light and had high upkeep. A major breakthrough came in the middle of the 19th century with a technique for coating glass with a metal film. This process (silver on glass) eventually lead to some bigger glass reflectors. Silvering has its own issues, in that coating must be reapplied usually every 2 years or so depending on conditions, and also it must be done very thinly so as to not affect the optical properties of the mirror.

A large glass reflector (122 cm diameter glass mirror) was established in Paris by 1876, but problems with figuring of that mirror meant that the Paris Observatory's 122 cm telescope was not used and did not have a good reputation for viewing.[71] The potential of metal coated glass became more apparent A.A. Common's 36 inch reflecting telescope by 1878.[71] (this won an astrophotography award)

The Warner and Swasey equatorial mount was shown in Chicago at the 1893 Colombia Exhibition, before it was moved to the Observatory.[12]

- Largest telescopes (all types) in 1910

| Name/Observatory | Aperture cm (in) |

Type | Location | Extant or Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvard 60-inch Reflector[72] | 1.524 m (60") | reflector – glass | Harvard College Observatory, USA | 1905–1931 |

| Hale 60-Inch Telescope | 1.524 m (60") | reflector – glass | Mt. Wilson Observatory; California, USA | 1908 |

| National Observatory, Paris | 122 cm (48") | reflector – glass | Paris, France | 1875–1943[65] |

| Great Melbourne Telescope[66] | 122 cm (48") | reflector – metal | Melbourne Observatory, Australia | 1878 |

| Yerkes Observatory[67] | 102 cm (40") | achromat | Williams Bay, Wisconsin, USA | 1897 |

| Meudon Observatory 1m[68] | 100 cm (39.4") | reflector-glass | Meudon Observatory/ Paris Observatory | 1891 [69] |

| James Lick telescope, Lick Observatory | 91 cm (36") | achromat | Mount Hamilton, California, USA | 1888 |

| Crossley Reflector[70] (Lick Observatory) | 91.4 cm (36") | reflector – glass | Mount Hamilton, California, USA | 1896 |

Legacy[edit]

By 1905, the largest telescope in the World was the Harvard 60-inch Reflector ( 1.524 m 60″) at Harvard College Observatory, USA.[72] Then in 1908, Mount Wilson Observatory matched that size with a 60-inch reflector of their own, and throughout the 20th century, increasingly larger reflectors would be established, aided also by refinements to mirror technology— vapor-deposited aluminum on low-thermal expansion glass, pioneered for the 200 inch (5 meter) Hale telescope of 1948.[73]

In the latter years of the 20th century, space observatories also marked a major advance, and somewhat less than a century after Yerkes, the Hubble Space Telescope, with a 2.4 meter reflector, was launched. Small refractors remain popular for astronomical photography, although issues with chromatic aberration were never really entirely solved for the lens. (Isaac Newton had solved this with the reflecting design, although the refractors are not without their merits.)

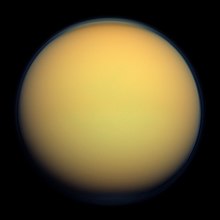

Great advancements such as astrophotography and the discovery of nebulas and different types of stars provided a major advance in this period. The importance of finely crafted mounts matched to a large aperture, harnessing the power of the basic equations of the telescopes design to bring the heavens into closer, brighter examination increased humankind's understanding of space and Earth's place in the Galaxy. Among the accomplishments, Kuiper discovered that Saturn's moon Titan has an atmosphere.[74]

See also[edit]

- List of largest optical refracting telescopes

- List of astronomical observatories

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 20th century

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 19th century

- List of telescope types

- Yerkes 41-inch reflector

References[edit]

- ^ Hale, George E. (1896). "Yerkes Observatory University of Chicago, Bulletin No. I." The Astrophysical Journal. 3: 215. Bibcode:1896ApJ.....3..215H. doi:10.1086/140199.

- ^ "Yerkes Observatory – Home". Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics: A Bit of History". astro.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ "About Yerkes Observatory". www.yerkesobservatory.org. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ "Observatory website". Archived from the original on May 14, 2011.

- ^ Carynski, Connor (May 1, 2020). "Foundation celebrates donation and takes ownership of Yerkes Observatory". lakegenevanews.net. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ url=http:www.yerkesobservatory.org}}

- ^ "The Conservation of the Historic Dearborn Telescope" (PDF). phy.olemiss.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Starr, Frederick (October 1897). "Science at the University of Chicago". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 51, no. May to October 1897. pp. 802–803. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ley, Willy; Menzel, Donald H.; Richardson, Robert S. (June 1965). "The Observatory on the Moon". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 132–150.

- ^ "Yerkes Observatory – 1893 History of Yerkes Observatory". Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e The General History of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. 1900. ISBN 9780521242561. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hale, George E. (1896). "Yerkes Observatory University of Chicago, Bulletin No. I." The Astrophysical Journal. 3: 215. Bibcode:1896ApJ.....3..215H. doi:10.1086/140199.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h O'Dell, C. R. (1967). "Yerkes Observatory University of Chicago, Williams Bay, Wisconsin". The Astronomical Journal. 72: 1158. Bibcode:1967AJ.....72.1158O. doi:10.1086/110394.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roth, Joshua (December 15, 2004). "Yerkes On the Block". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "Constructive point of view". chronicle.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Darling, David. "Yerkes Observatory". www.daviddarling.info. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Dell, C. R. (1969). "Yerkes Observatory, Williams Bay, Wisconsin. Report 1967-1968". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 1: 135. Bibcode:1969BAAS....1..135O. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Dell, C. R. (1969). "Yerkes Observatory, Williams Bay, Wisconsin. Report 1967-1968". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 1: 135. Bibcode:1969BAAS....1..135O. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ Krugler, Joel I.; Witt, Adolf N. (1969). "An Alignment Technique for Ritchey-Chrétien Telescopes". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 81 (480): 254. Bibcode:1969PASP...81..254K. doi:10.1086/128768. S2CID 119738670.

- ^ Wild, W. J.; Kibblewhite, E. J.; Shi, F.; Carter, B.; Kelderhouse, G.; Vuilleumier, R.; Manning, H. L. (May 31, 1994). "Field tests of the Wavefront Control Experiment". In Ealey, Mark A.; Merkle, Fritz (eds.). Adaptive Optics in Astronomy. Vol. 2201. pp. 1121–1134. Bibcode:1994SPIE.2201.1121W. doi:10.1117/12.176024. S2CID 119806080. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ritchey, G. W. (1901). "The Two-Foot Reflecting Telescope of the Yerkes Observatory". The Astrophysical Journal. 14: 217. Bibcode:1901ApJ....14..217R. doi:10.1086/140861.

- ^ "1901ApJ....14..217R Page 225". Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ Darling, David. "Yerkes Observatory". www.daviddarling.info. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ O'Dell, C. R. (1969). "Yerkes Observatory, Williams Bay, Wisconsin. Report 1967-1968". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 1: 135. Bibcode:1969BAAS....1..135O. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Darling, David. "Yerkes Observatory". www.daviddarling.info. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ Morgan, W. W. (1963). "Yerkes Observatory". The Astronomical Journal. 68: 756. Bibcode:1963AJ.....68..756M. doi:10.1086/109213.

- ^ "24 Inch (0.61 Meters) Telescope for University of Chicago, Yerkes Observatory – Boller and Chivens: A History "Where Precision is a Way of Life" – Boller and Chivens were makers of Telescopes and Precision Instruments". bollerandchivens.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "24-Inch (0.61 meter) Telescope Specifications – Boller and Chivens: A History "Where Precision is a Way of Life" – Boller and Chivens were makers of Telescopes and Precision Instruments". bollerandchivens.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Yerkes Observatory : Photographic Archive : The University of Chicago". photoarchive.lib.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "VT Snow Solar Telescope". Mount Wilson Observatory. January 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Barnard, E. E. (1905). "The Bruce photographic telescope of the Yerkes Observatory". The Astrophysical Journal. 21: 35. Bibcode:1905ApJ....21...35B. doi:10.1086/141188.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Famos Astrograph/Camera Detail". www.artdeciel.com. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ Steinicke, Wolfgang (August 19, 2010). Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer's New General Catalogue. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139490108. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Yerkes Observatory: A century of stellar science". chronicle.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "Meetings of the AAS: 1897–1906 | Historical Astronomy Division". had.aas.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ Struve, Otto (1947). "The Yerkes Observatory, 1897–1947". Popular Astronomy. 55: 413. Bibcode:1947PA.....55..413S. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ "Yerkes Observatory-R & D-HAWC". Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "The Yerkes Observatory Photographic Plates". Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ Morgan, William Wilson; Keenan, Philip Childs; Kellman, Edith (1943). An atlas of stellar spectra, with an outline of spectral classification. The University of Chicago Press. Bibcode:1943assw.book.....M. OCLC 1806249.

- ^ Morgan, William Wilson; Keenan, Philip Childs (1973). "Spectral Classification". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 11: 29–50. Bibcode:1973ARA&A..11...29M. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.11.090173.000333.

- ^ "aas-donahue-yerkes-letter" (PDF). American Astronomical Society. July 10, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Astronomical Journal. American Institute of Physics. 1900. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Science, Elizabeth Howell 2014-08-16T02:26:07Z; Astronomy. "Yerkes Observatory: Home of Largest Refracting Telescope". Space.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gale, Henry G. (July 1931). "Albert A. Michelson". The Astrophysical Journal. 74 (1): 1–9. Bibcode:1931ApJ....74....1G. doi:10.1086/143320.

- ^ "The Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics | A Bit of History". astro.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Greg Burns. "Yerkes plan changes focus". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 8, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ Williams, Scott (March 7, 2018). "Yerkes Observatory closing after 100 years on lakefront". Lake Geneva News. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ "New Group Submits Proposal to Keep Yerkes Open". www.chicagomaroon.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "Geneva Lake Astrophysics and STEAM". Geneva Lake Astrophysics and STEAM. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "Original bequest letter for Yerkes Observatory holds up its future". The Chicago Maroon. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "Yerkes Observatory". Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Grainger Editorial Staff (February 8, 2023). "Yerkes Observatory: Restoring the World's Largest Refracting Telescope". Includes photos, video.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Not-Quite Closing of Yerkes Observatory". Sky & Telescope. March 16, 2018. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "Agreement provides for preservation of historic Yerkes Observatory". www-news.uchicago.edu (Press release). Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Observatory Dr Property Record". Wisconsin Historical Society. January 1, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "CONTENTdm". hdl.huntington.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cruikshank, Dale P.; Sheehan, William (2018). Discovering Pluto: Exploration at the Edge of the Solar System. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816534319. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Kron, Richard (July 6, 2018). "The scientific legacy of Yerkes Observatory". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.6.4.20180706a. S2CID 240363393. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Schultz, Chris (October 9, 2019). "Williams Bay Centennial: A century in story and pictures". Lake Geneva News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Trees at Yerkes Observatory" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "Yerkes Observatory Photographs Now Online – The University of Chicago Library News – The University of Chicago Library". www.lib.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "Recent Improvements on the University Campus". The University Record. 13 (1): 29. July 1908. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "National Park Service: Astronomy and Astrophysics (Yerkes Observatory)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hollis, H. P. (1914). "Large telescopes". The Observatory. 37: 245. Bibcode:1914Obs....37..245H. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Largest optical telescopes of the world". stjarnhimlen.se. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The 40-inch". Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Popular Astronomy". 19 (9). November 1911: 584. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b "Le télescope de 1 mètre - Observatoire de Paris - PSL Centre de recherche en astronomie et astrophysique". www.obspm.fr. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mt. Hamilton Telescopes: CrossleyTelescope". www.ucolick.org. Archived from the original on September 2, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gillespie, Richard (November 1, 2011). The Great Melbourne Telescope. Museum Victoria. ISBN 9781921833298. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New Harvard Telescope: Sixty-Inch Reflector, Biggest in the World, Being Set Up". The New York Times. April 6, 1905. p. 9. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "The 200-inch Hale Telescope". www.astro.caltech.edu. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Science, Elizabeth Howell 2014-08-16T02:26:07Z; Astronomy. "Yerkes Observatory: Home of Largest Refracting Telescope". Space.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

Media related to Yerkes Observatory at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yerkes Observatory at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Description and history[dead link] from the National Park Service, archived at [1].

- Save Yerkes Archived June 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Yerkes Study Group

- Geneva Lake Conservancy

- GLAS Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Guide to the University of Chicago Yerkes Observatory Logbooks and Notebooks 1892–1988 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- Guide to the University of Chicago, Yerkes Observatory, Office of the Director Records 1891–1946 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center