Русско-украинская война

| Русско-украинская война | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть конфликтов на территории бывшего Советского Союза | |||||||||

Clockwise from top left:

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Supplied by: For details, see Russian military suppliers | Supplied by: For countries providing aid to Ukraine since 2022, see military aid to Ukraine | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

For details of strengths and units involved at key points in the conflict, see: | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Reports vary widely, but tens of thousands at a minimum.[3][4] See Casualties of the Russo-Ukrainian War for details. | |||||||||

Продолжающаяся российско-украинская война. [с] началась в феврале 2014 года. После украинской Революции достоинства Россия оккупировала и аннексировала Крым у Украины и поддержала пророссийских сепаратистов, сражающихся с украинскими военными в войне на Донбассе . Эти первые восемь лет конфликта также включали инциденты на море и кибервойны . В феврале 2022 года Россия начала полномасштабное вторжение в Украину и начала оккупировать большую часть страны, положив начало крупнейшему конфликту в Европе со времен Второй мировой войны .

В начале 2014 года протесты Евромайдана привели к Революции достоинства и свержению пророссийского президента Украины Виктора Януковича . Вскоре после этого на востоке и юге Украины вспыхнули пророссийские волнения , а без опознавательных знаков российские войска оккупировали Крым . Россия вскоре аннексировала Крым после весьма спорного референдума . В апреле 2014 года поддерживаемые Россией боевики захватили города Украины на востоке и провозгласили Донецкую Народную Республику (ДНР) и Луганскую Народную Республику (ЛНР) независимыми государствами, начав войну на Донбассе. Россия тайно поддерживала сепаратистов своими войсками, танками и артиллерией, а Украина не смогла полностью вернуть себе территорию. В феврале 2015 года Россия и Украина подписали Минские соглашения II о прекращении конфликта, но в последующие годы они так и не были полностью реализованы. Война на Донбассе вылилась в жестокий, но статичный конфликт между Украиной и российскими и сепаратистскими силами, сопровождавшийся многими кратковременными перемириями, но не прочным миром и небольшими изменениями в территориальном контроле.

Beginning in 2021, there was a massive Russian military buildup near Ukraine's borders, including within neighbouring Belarus. Russian officials repeatedly denied plans to attack Ukraine. Russia's president Vladimir Putin expressed irredentist views and denied Ukraine's right to exist. He demanded that Ukraine be barred from ever joining the NATO military alliance. In early 2022, Russia recognized the DPR and LPR as independent states.

On 24 February 2022, Putin announced a "special military operation" to "demilitarize and denazify" Ukraine, claiming Russia had no plans to occupy the country. The Russian invasion that followed was internationally condemned; many countries imposed sanctions against Russia and increased existing sanctions. In the face of fierce resistance, Russia abandoned an attempt to take Kyiv in early April. From August, Ukrainian forces began recapturing territories in the north-east and south. In late September, Russia declared the annexation of four partially-occupied regions, which was internationally condemned. Russia spent the winter conducting inconclusive offensives in the Donbas. In spring 2023, Russia dug into positions ahead of another Ukrainian counteroffensive, which failed to gain significant ground. The war has resulted in a refugee crisis and tens of thousands of deaths.

Background

Independent Ukraine and the Orange Revolution

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1991, Ukraine and Russia maintained close ties. In 1994, Ukraine agreed to accede to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons as a non-nuclear-weapon state.[5] Former Soviet nuclear weapons in Ukraine were removed and dismantled.[6] In return, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States agreed to uphold the territorial integrity and political independence of Ukraine through the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances.[7][8] In 1999, Russia was one of the signatories of the Charter for European Security, which "reaffirmed the inherent right of each and every participating State to be free to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve."[9] In the years after the dissolution of the USSR, several former Eastern Bloc countries joined NATO, partly in response to regional security threats involving Russia such as the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, the War in Abkhazia (1992–1993) and the First Chechen War (1994–1996). Putin said Western powers broke promises not to let any Eastern European countries join.[10][11]

The 2004 Ukrainian presidential election was controversial. During the election campaign, opposition candidate Viktor Yushchenko was poisoned by TCDD dioxin;[12][13] he later accused Russia of involvement.[14] In November, Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych was declared the winner, despite allegations of vote-rigging by election observers.[15] During a two-month period which became known as the Orange Revolution, large peaceful protests successfully challenged the outcome. After the Supreme Court of Ukraine annulled the initial result due to widespread electoral fraud, a second round re-run was held, bringing to power Yushchenko as president and Yulia Tymoshenko as prime minister, and leaving Yanukovych in opposition.[16] The Orange Revolution is often grouped together with other early-21st century protest movements, particularly within the former USSR, known as colour revolutions. According to Anthony Cordesman, Russian military officers viewed such colour revolutions as attempts by the US and European states to destabilise neighbouring countries and undermine Russia's national security.[17] Russian President Vladimir Putin accused organisers of the 2011–2013 Russian protests of being former advisors to Yushchenko, and described the protests as an attempt to transfer the Orange Revolution to Russia.[18] Rallies in favour of Putin during this period were called "anti-Orange protests".[19]

At the 2008 Bucharest summit, Ukraine and Georgia sought to join NATO. The response among NATO members was divided. Western European countries opposed offering Membership Action Plans (MAP) to Ukraine and Georgia in order to avoid antagonising Russia, while US President George W. Bush pushed for their admission.[20] NATO ultimately refused to offer Ukraine and Georgia MAPs, but also issued a statement agreeing that "these countries will become members of NATO" at some point. Putin strongly opposed Georgia and Ukraine's NATO membership bids.[21] By January 2022, the possibility of Ukraine joining NATO remained remote.[22]

In 2009, Yanukovych announced his intent to again run for president in the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election,[23] which he subsequently won.[24] In November 2013, a wave of large, pro–European Union (EU) protests erupted in response to Yanukovych's sudden decision not to sign the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement, instead choosing closer ties to Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. On 22 February 2013, the Ukrainian parliament overwhelmingly approved of finalizing Ukraine's agreement with the EU.[25] Subsequently, Russia pressured Ukraine to reject this agreement by threatening sanctions. Kremlin adviser Sergei Glazyev stated that if the agreement was signed, Russia could not guarantee Ukraine's status as a state.[26][27]

Euromaidan, Revolution of Dignity, and pro-Russian unrest

On 21 February 2014, following months of protests as part of the Euromaidan movement, Yanukovych and the leaders of the parliamentary opposition signed a settlement agreement that provided for early elections. The following day, Yanukovych fled from the capital ahead of an impeachment vote that stripped him of his powers as president.[28][29][30][31] On 23 February, the Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) adopted a bill to repeal the 2012 law which made Russian an official language.[32] The bill was not enacted,[33] but the proposal provoked negative reactions in the Russian-speaking regions of Ukraine,[34] intensified by Russian media claiming that the ethnic Russian population was in imminent danger.[35]

On 27 February, an interim government was established and early presidential elections were scheduled. The following day, Yanukovych resurfaced in Russia and in a press conference, declared that he remained the acting president of Ukraine, just as Russia was commencing a military campaign in Crimea. Leaders of Russian-speaking eastern regions of Ukraine declared continuing loyalty to Yanukovych,[29][36] triggering the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine.

Russian military bases in Crimea

At the onset of the Crimean conflict, Russia had roughly 12,000 military personnel from the Black Sea Fleet,[35] in several locations in the Crimean peninsula such as Sevastopol, Kacha, Hvardiiske, Simferopol Raion, Sarych, and others. In 2005 a dispute broke out between Russia and Ukraine over control of the Sarych cape lighthouse near Yalta, and a number of other beacons.[37][38] Russian presence was allowed by the basing and transit agreement with Ukraine. Under this agreement, the Russian military in Crimea was constrained to a maximum of 25,000 troops. Russia was required to respect the sovereignty of Ukraine, honor its legislation, not interfere in the internal affairs of the country, and show their "military identification cards" when crossing the international border.[39] Early in the conflict, the agreement's generous troop limit allowed Russia to significantly strengthen its military presence, deploy special forces and other required capabilities to conduct the operation in Crimea, under the pretext of addressing security concerns.[35]

According to the original treaty on the division of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet signed in 1997, Russia was allowed to have its military bases in Crimea until 2017, after which it would evacuate all military units including its portion of the Black Sea Fleet from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol. On 21 April 2010, former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych signed a new deal with Russia, known as the Kharkiv Pact, to resolve the 2009 Russia–Ukraine gas dispute. The pact extended Russia's stay in Crimea to 2042, with an option to renew.[40]

Legality and declaration of war

No formal declaration of war has been issued in the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. When Putin announced the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, he claimed to commence a "special military operation", side-stepping a formal declaration of war.[41] The statement was, however, regarded as a declaration of war by the Ukrainian government[42] and reported as such by many international news sources.[43][44] While the Ukrainian parliament refers to Russia as a "terrorist state" in regard to its military actions in Ukraine,[45] it has not issued a formal declaration of war on its behalf.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine violated international law (including the Charter of the United Nations).[53][54][55][56] The invasion has also been called a crime of aggression under international criminal law[57] and under some countries' domestic criminal codes – including those of Ukraine and Russia – although procedural obstacles exist to prosecutions under these laws.[58][59]

History

Russian annexation of Crimea (2014)

In late February 2014, Russia began to occupy Crimea, marking the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[60][61][62][63] On 22 and 23 February, in the relative power vacuum immediately after the ousting of Yanukovych,[64] Russian troops and special forces were moved close to the border with Crimea.[62] On 27 February, Russian forces without insignia began to occupy Crimea.[65][66] Russia consistently denied that the soldiers were theirs, instead claiming they were local "self-defense" units. They seized the Crimean parliament and government buildings, as well as setting up checkpoints to restrict movement and cut off the Crimean peninsula from the rest of Ukraine.[67][68][69][70] In the following days, unmarked Russian special forces occupied airports and communications centers,[71] and blockaded Ukrainian military bases, such as the Southern Naval Base. Russian cyberattacks shut down websites associated with the Ukrainian government, news media, and social media. Cyberattacks also enabled Russian access to the mobile phones of Ukrainian officials and members of parliament, further disrupting communications.[72] On 1 March, the Russian parliament approved the use of armed forces in Crimea.[71]

While Russian special forces occupied Crimea's parliament, it dismissed the Crimean government, installed the pro-Russian Aksyonov government, and announced a referendum on Crimea's status. The referendum was held under Russian occupation and, according to the Russian-installed authorities, the result was in favor of joining Russia. It annexed Crimea on 18 March 2014. Following this, Russian forces seized Ukrainian military bases in Crimea and captured their personnel. On 24 March, Ukraine ordered its remaining troops to withdraw; by 30 March, all Ukrainian forces had left the peninsula.

On 15 April, the Ukrainian parliament declared Crimea a territory temporarily occupied by Russia.[73] After the annexation, the Russian government militarized the peninsula and made nuclear threats.[74] Putin said that a Russian military task force would be established in Crimea.[75] In November, NATO stated that it believed Russia was deploying nuclear-capable weapons to Crimea.[76] After the annexation of Crimea, some NATO members began providing training for the Ukrainian army.[77]

War in the Donbas (2014–2015)

Pro-Russia unrest

From late February 2014, demonstrations by pro-Russian and anti-government groups took place in major cities across the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine.[78] The first protests across southern and eastern Ukraine were largely native expressions of discontent with the new Ukrainian government.[78][79] Russian involvement at this stage was limited to voicing support for the demonstrations.[79][80] Russia exploited this, however, launching a coordinated political and military campaign against Ukraine.[79][81] Putin gave legitimacy to the separatists when he described the Donbas as part of "New Russia" (Novorossiya), and expressed bewilderment as to how the region had ever become part of Ukraine.[82]

Russia continued to marshal forces near Ukraine's eastern border in late March, reaching 30–40,000 troops by April.[83][35] The deployment was used to threaten escalation and disrupt Ukraine's response.[35] This threat forced Ukraine to divert forces to its borders instead of the conflict zone.[35]

Ukrainian authorities cracked down on the pro-Russian protests and arrested local separatist leaders in early March. Those leaders were replaced by people with ties to the Russian security services and interests in Russian businesses.[84] By April 2014, Russian citizens had taken control of the separatist movement, supported by volunteers and materiel from Russia, including Chechen and Cossack fighters.[85][86][87][88] According to Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) commander Igor Girkin, without this support in April, the movement would have dissipated, as it had in Kharkiv and Odesa.[89] The separatist groups held disputed referendums in May,[90][91][92] which were not recognised by Ukraine or any other UN member state.[90]

Armed conflict

In April 2014, armed conflict began in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed separatists and Ukraine. On 12 April, a fifty-man unit of pro-Russian militants seized the towns of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk.[93] The heavily armed men were Russian Armed Forces "volunteers" under the command of former GRU colonel Igor Girkin ('Strelkov').[93][94] They had been sent from Russian-occupied Crimea and wore no insignia.[93] Girkin said that this action sparked the Donbas War. He said "I'm the one who pulled the trigger of war. If our unit hadn't crossed the border, everything would have fizzled out".[95][96]

In response, on 15 April the interim Ukrainian government launched an "Anti-Terrorist Operation" (ATO); however, Ukrainian forces were poorly prepared and ill-positioned and the operation quickly stalled.[97] By the end of April, Ukraine announced it had lost control of the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk. It claimed to be on "full combat alert" against a possible Russian invasion and reinstated conscription to its armed forces.[98] During May, the Ukrainian campaign focused on containing the separatists by securing key positions around the ATO zone to position the military for a decisive offensive once Ukraine's national mobilization had completed.

As conflict between the separatists and the Ukrainian government escalated in May, Russia began to employ a "hybrid approach", combining disinformation tactics, irregular fighters, regular Russian troops, and conventional military support.[99][100][101] The First Battle of Donetsk Airport followed the Ukrainian presidential elections. It marked a turning point in conflict; it was the first battle between the separatists and the Ukrainian government that involved large numbers of Russian "volunteers".[102][103]: 15 According to Ukraine, at the height of the conflict in the summer of 2014, Russian paramilitaries made up between 15% and 80% of the combatants.[87] From June Russia trickled in arms, armor, and munitions.

On 17 July 2014, Russian-controlled forces shot down a passenger aircraft, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, as it was flying over eastern Ukraine.[104] Investigations and the recovery of bodies began in the conflict zone as fighting continued.[105][106][107]

By the end of July, Ukrainian forces were pushing into cities, to cut off supply routes between the two, isolating Donetsk and attempting to restore control of the Russo-Ukrainian border. By 28 July, the strategic heights of Savur-Mohyla were under Ukrainian control, along with the town of Debaltseve, an important railroad hub.[108] These operational successes of Ukrainian forces threatened the existence of the DPR and LPR statelets, prompting Russian cross-border shelling targeted at Ukrainian troops on their own soil, from mid-July onwards.[109]

August 2014 Russian invasion

After a series of military defeats and setbacks for the separatists, who united under the banner of "Novorossiya",[110][111] Russia dispatched what it called a "humanitarian convoy" of trucks across the border in mid-August 2014. Ukraine called the move a "direct invasion".[112] Ukraine's National Security and Defence Council reported that convoys were arriving almost daily in November (up to 9 convoys on 30 November) and that their contents were mainly arms and ammunition. Strelkov claimed that in early August, Russian servicemen, supposedly on "vacation" from the army, began to arrive in Donbas.[113]

By August 2014, the Ukrainian "Anti-Terrorist Operation" shrank the territory under pro-Russian control, and approached the border.[114] Igor Girkin urged Russian military intervention, and said that the combat inexperience of his irregular forces, along with recruitment difficulties amongst the local population, had caused the setbacks. He stated, "Losing this war on the territory that President Vladimir Putin personally named New Russia would threaten the Kremlin's power and, personally, the power of the president".[115]

In response to the deteriorating situation, Russia abandoned its hybrid approach, and began a conventional invasion on 25 August 2014.[114][116] On the following day, the Russian Defence Ministry said these soldiers had crossed the border "by accident".[117][118][119] According to Nikolai Mitrokhin's estimates, by mid-August 2014 during the Battle of Ilovaisk, between 20,000 and 25,000 troops were fighting in the Donbas on the separatist side, and only 40–45% were "locals".[120]

On 24 August 2014, Amvrosiivka was occupied by Russian paratroopers,[121] supported by 250 armoured vehicles and artillery pieces.[122] The same day, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko referred to the operation as Ukraine's "Patriotic War of 2014" and a war against external aggression.[123][124] On 25 August, a column of Russian military vehicles was reported to have crossed into Ukraine near Novoazovsk on the Azov sea coast. It appeared headed towards Ukrainian-held Mariupol,[125][126][127][128][129] in an area that had not seen pro-Russian presence for weeks.[130] Russian forces captured Novoazovsk.[131] and Russian soldiers began deporting Ukrainians who did not have an address registered within the town.[132] Pro-Ukrainian anti-war protests took place in Mariupol.[132][133] The UN Security Council called an emergency meeting.[134]

The Pskov-based 76th Guards Air Assault Division allegedly entered Ukrainian territory in August and engaged in a skirmish near Luhansk, suffering 80 dead. The Ukrainian Defence Ministry said that they had seized two of the unit's armoured vehicles near Luhansk, and reported destroying another three tanks and two armoured vehicles in other regions.[135]

The speaker of Russia's upper house of parliament and Russian state television channels acknowledged that Russian soldiers entered Ukraine, but referred to them as "volunteers".[136] A reporter for Novaya Gazeta, an opposition newspaper in Russia, stated that the Russian military leadership paid soldiers to resign their commissions and fight in Ukraine in the early summer of 2014, and then began ordering soldiers into Ukraine.[137] Russian opposition MP Lev Shlosberg made similar statements, although he said combatants from his country are "regular Russian troops", disguised as units of the DPR and LPR.[138]

In early September 2014, Russian state-owned television channels reported on the funerals of Russian soldiers who had died in Ukraine, but described them as "volunteers" fighting for the "Russian world". Valentina Matviyenko, a top United Russia politician, also praised "volunteers" fighting in "our fraternal nation".[136] Russian state television for the first time showed the funeral of a soldier killed fighting in Ukraine.[139]

Mariupol offensive and first Minsk ceasefire

On 3 September, Poroshenko said he and Putin had reached a "permanent ceasefire" agreement.[140] Russia denied this, denying that it was a party to the conflict, adding that "they only discussed how to settle the conflict".[141][142] Poroshenko then recanted.[143][144] On 5 September Russia's Permanent OSCE Representative Andrey Kelin, said that it was natural that pro-Russian separatists "are going to liberate" Mariupol. Ukrainian forces stated that Russian intelligence groups had been spotted in the area. Kelin said 'there might be volunteers over there.'[145] On 4 September 2014, a NATO officer said that several thousand regular Russian forces were operating in Ukraine.[146]

On 5 September 2014, the Minsk Protocol ceasefire agreement drew a line of demarcation between Ukraine and separatist-controlled portions of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

End of 2014 and Minsk II agreement

On 7 and 12 November, NATO officials reconfirmed the Russian presence, citing 32 tanks, 16 howitzer cannons and 30 trucks of troops entering the country.[147] US general Philip M. Breedlove said "Russian tanks, Russian artillery, Russian air defence systems and Russian combat troops" had been sighted.[76][148] NATO said it had seen an increase in Russian tanks, artillery pieces and other heavy military equipment in Ukraine and renewed its call for Moscow to withdraw its forces.[149] The Chicago Council on Global Affairs stated that Russian separatists enjoyed technical advantages over the Ukrainian army since the large inflow of advanced military systems in mid-2014: effective anti-aircraft weapons ("Buk", MANPADS) suppressed Ukrainian air strikes, Russian drones provided intelligence, and Russian secure communications system disrupted Ukrainian communications intelligence. The Russian side employed electronic warfare systems that Ukraine lacked. Similar conclusions about the technical advantage of the Russian separatists were voiced by the Conflict Studies Research Centre.[150] At the United Nations Security Council meeting on 12 November, the United Kingdom's representative accused Russia of intentionally constraining OSCE observation missions' capabilities, stating that the observers were allowed to monitor only two kilometers of border, and drones deployed to extend their capabilities were jammed or shot down.[151][non-primary source needed]

In January 2015, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Mariupol represented the three battle fronts.[153] Poroshenko described a dangerous escalation on 21 January amid reports of more than 2,000 additional Russian troops, 200 tanks and armed personnel carriers crossing the border. He abbreviated his visit to the World Economic Forum because of his concerns.[154]

A new package of measures to end the conflict, known as Minsk II, was agreed on 15 February 2015.[155] On 18 February, Ukrainian forces withdrew from Debatlseve, in the last high-intensity battle of the Donbas war until 2022. In September 2015 the United Nations Human Rights Office estimated that 8000 casualties had resulted from the conflict.[156]

Line of conflict stabilizes (2015–2021)

After the Minsk agreements, the war settled into static trench warfare around the agreed line of contact, with few changes in territorial control. The conflict was marked by artillery duels, special forces operations, and trench warfare. Hostilities never ceased for a substantial period of time, but continued at a low level despite repeated attempts at ceasefire. In the months after the fall of Debaltseve, minor skirmishes continued along the line of contact, but no territorial changes occurred. Both sides began fortifying their position by building networks of trenches, bunkers and tunnels, turning the conflict into static trench warfare.[157][158] The relatively static conflict was labelled "frozen" by some,[159] but Russia never achieved this as the fighting never stopped.[160][161] Between 2014 and 2022 there were 29 ceasefires, each agreed to remain in force indefinitely. However, none of them lasted more than two weeks.[162]

US and international officials continued to report the active presence of Russian military in eastern Ukraine, including in the Debaltseve area.[163] In 2015, Russian separatist forces were estimated to number around 36,000 troops (compared to 34,000 Ukrainian), of whom 8,500–10,000 were Russian soldiers. Additionally, around 1,000 GRU troops were operating in the area.[164] Another 2015 estimate held that Ukrainian forces outnumbered Russian forces 40,000 to 20,000.[165] In 2017, on average one Ukrainian soldier died in combat every three days,[166] with an estimated 6,000 Russian and 40,000 separatist troops in the region.[167][168]

Cases of killed and wounded Russian soldiers were discussed in local Russian media.[169] Recruiting for Donbas was performed openly via veteran and paramilitary organisations. Vladimir Yefimov, leader of one such organisation, explained how the process worked in the Ural area. The organisation recruited mostly army veterans, but also policemen, firefighters etc. with military experience. The cost of equipping one volunteer was estimated at 350,000 rubles (around $6500) plus salary of 60,000 to 240,000 rubles per month.[170] The recruits received weapons only after arriving in the conflict zone. Often, Russian troops traveled disguised as Red Cross personnel.[171][172][173][174] Igor Trunov, head of the Russian Red Cross in Moscow, condemned these convoys, saying they complicated humanitarian aid delivery.[175] Russia refused to allow OSCE to expand its mission beyond two border crossings.[176]

The volunteers were issued a document claiming that their participation was limited to "offering humanitarian help" to avoid Russian mercenary laws. Russia's anti-mercenary legislation defined a mercenary as someone who "takes part [in fighting] with aims counter to the interests of the Russian Federation".[170]

In August 2016, the Ukrainian intelligence service, the SBU, published telephone intercepts from 2014 of Sergey Glazyev (Russian presidential adviser), Konstantin Zatulin, and other people in which they discussed covert funding of pro-Russian activists in Eastern Ukraine, the occupation of administration buildings and other actions that triggered the conflict.[177] As early as February 2014, Glazyev gave direct instructions to various pro-Russian parties on how to take over local administration offices, what to do afterwards, how to formulate demands, and promised support from Russia, including "sending our guys".[178][179][180]

2018 Kerch Strait incident

Russia gained de facto control of the Kerch Strait in 2014. In 2017, Ukraine appealed to a court of arbitration over the use of the strait. By 2018 Russia had built a bridge over the strait, limiting the size of ships that could pass through, imposed new regulations, and repeatedly detained Ukrainian vessels.[181] On 25 November 2018, three Ukrainian boats traveling from Odesa to Mariupol were seized by Russian warships; 24 Ukrainian sailors were detained.[182][183] A day later on 26 November 2018, the Ukrainian parliament overwhelmingly backed the imposition of martial law along Ukraine's coastal regions and those bordering Russia.[184]

2019–2020

More than 110 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in the conflict in 2019.[185] In May 2019, newly elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy took office promising to end the war in Donbas.[185] In December 2019, Ukraine and pro-Russian separatists began swapping prisoners of war. Around 200 prisoners were exchanged on 29 December 2019.[186][187][188][189] According to Ukrainian authorities, 50 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in 2020.[190] Between 2019 and 2021, Russia issued over 650,000 internal Russian passports to Ukrainians.[191][192]

There were 27 conflict-related civilian deaths in 2019, 26 deaths in 2020, and 25 deaths in 2021, over half of them from mines and unexploded ordnance.[193]

Russian military buildup around Ukraine (2021–2022)

From March to April 2021, Russia commenced a major military build-up near the border, followed by a second build-up between October 2021 to February 2022 in Russia and Belarus.[194] Throughout, the Russian government repeatedly denied it had plans to attack Ukraine.[195][196]

In early December 2021, following Russian denials, the US released intelligence of Russian invasion plans, including satellite photographs showing Russian troops and equipment near the border.[197] The intelligence reported a Russian list of key sites and individuals to be killed or neutralized.[198] The US released multiple reports that accurately predicted the invasion plans.[198]

Russian accusations and demands

In the months preceding the invasion, Russian officials accused Ukraine of inciting tensions, Russophobia, and repressing Russian speakers. They made multiple security demands of Ukraine, NATO, and other EU countries. On 9 December 2021 Putin said that "Russophobia is a first step towards genocide".[199][200] Putin's claims were dismissed by the international community,[201] and Russian claims of genocide were rejected as baseless.[202][203][204] In a 21 February speech,[205] Putin questioned the legitimacy of the Ukrainian state, repeating an inaccurate claim that "Ukraine never had a tradition of genuine statehood".[206] He incorrectly stated that Vladimir Lenin had created Ukraine, by carving a separate Soviet Republic out of what Putin said was Russian land, and that Nikita Khrushchev "took Crimea away from Russia for some reason and gave it to Ukraine" in 1954.[207]

Putin falsely claimed that Ukrainian society and government were dominated by neo-Nazism, invoking the history of collaboration in German-occupied Ukraine during World War II,[208][209] and echoing an antisemitic conspiracy theory that cast Russian Christians, rather than Jews, as the true victims of Nazi Germany.[210][201] Ukraine does have a far-right fringe, including the neo-Nazi linked Azov Battalion and Right Sector.[211][209] Analysts described Putin's rhetoric as greatly exaggerated.[212][208] Zelenskyy, who is Jewish, stated that his grandfather served in the Soviet army fighting against the Nazis;[213] three of his family members were killed in the Holocaust.[212]

During the second build-up, the Russian government demanded NATO end all activity in its Eastern European member states and ban Ukraine or any former Soviet state from ever joining NATO, among other demands.[215] A treaty to prevent Ukraine joining NATO would go against the alliance's "open door" policy and the right of countries to choose their own security,[216] although NATO had made no progress on Ukraine's requests to join.[217] NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg replied that "Russia has no say" on whether Ukraine joins, and that "Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence to try to control their neighbors".[218] NATO offered to improve communication with Russia and discuss limits on missile placements and military exercises, as long as Russia withdrew troops from Ukraine's borders,[219] but Russia did not withdraw.

Prelude to full invasion

Fighting in Donbas escalated significantly from 17 February 2022 onwards.[220] The Ukrainians and the pro-Russian separatists each accused the other of attacks.[221][222] There was a sharp increase in artillery shelling by the Russian-led militants in Donbas, which was considered by Ukraine and its supporters to be an attempt to provoke the Ukrainian army or create a pretext for invasion.[223][224][225] On 18 February, the Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics ordered mandatory emergency evacuations of civilians from their respective capital cities,[226][227][228] although observers noted that full evacuations would take months.[229] The Russian government intensified its disinformation campaign, with Russian state media promoting fabricated videos (false flags) on a nearly hourly basis purporting to show Ukrainian forces attacking Russia.[230] Many of the disinformation videos were amateurish, and evidence showed that the claimed attacks, explosions, and evacuations in Donbas were staged by Russia.[230][231][232]

On 21 February at 22:35 (UTC+3),[233] Putin announced that the Russian government would diplomatically recognize the Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics.[234] The same evening, Putin directed that Russian troops deploy into Donbas, in what Russia referred to as a "peacekeeping mission".[235][236] On 22 February, the Federation Council unanimously authorised Putin to use military force outside Russia.[237] In response, Zelenskyy ordered the conscription of army reservists;[238] The following day, Ukraine's parliament proclaimed a 30-day nationwide state of emergency and ordered the mobilisation of all reservists.[239][240][241] Russia began to evacuate its embassy in Kyiv.[242]

On the night of 23 February,[243] Zelenskyy gave a speech in Russian in which he appealed to the citizens of Russia to prevent war.[244][245] He rejected Russia's claims about neo-Nazis and stated that he had no intention of attacking the Donbas.[246] Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said on 23 February that the separatist leaders in Donetsk and Luhansk had sent a letter to Putin stating that Ukrainian shelling had caused civilian deaths and appealing for military support.[247]

Full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022–present)

The Russian invasion of Ukraine began on the morning of 24 February 2022,[248] when Putin announced a "special military operation" to "demilitarise and denazify" Ukraine.[249][250] Minutes later, missiles and airstrikes hit across Ukraine, including Kyiv, shortly followed by a large ground invasion along multiple fronts.[251][252] Zelenskyy declared martial law and a general mobilisation of all male Ukrainian citizens between 18 and 60, who were banned from leaving the country.[253][254]

Russian attacks were initially launched on a northern front from Belarus towards Kyiv, a southern front from Crimea, and a south-eastern front from Luhansk and Donetsk and towards Kharkiv.[255][256] In the northern front, amidst heavy losses and strong Ukrainian resistance surrounding Kyiv, Russia's advance stalled in March, and by April its troops retreated. On 8 April, Russia placed its forces in southern and eastern Ukraine under the command of General Aleksandr Dvornikov, and some units withdrawn from the north were redeployed to the Donbas.[257] On 19 April, Russia launched a renewed attack across a 500 kilometres (300 mi) long front extending from Kharkiv to Donetsk and Luhansk.[258] By 13 May, a Ukraine counter-offensive had driven back Russian forces near Kharkiv. By 20 May, Mariupol fell to Russian troops following a prolonged siege of the Azovstal steel works.[259][260] Russian forces continued to bomb both military and civilian targets far from the frontline.[261][262] The war caused the largest refugee and humanitarian crisis within Europe since the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s;[263][264] the UN described it as the fastest-growing such crisis since World War II.[265] In the first week of the invasion, the UN reported over a million refugees had fled Ukraine; this subsequently rose to over 7,405,590 by 24 September, a reduction from over eight million due to some refugees' return.[266][267]

Ukrainian forces launched counteroffensives in the south in August, and in the northeast in September. On 30 September, Russia annexed four oblasts of Ukraine which it had partially conquered during the invasion.[268] This annexation was generally unrecognized and condemned by the countries of the world.[269] After Putin announced that he would begin conscription drawn from the 300,000 citizens with military training and potentially the pool of about 25 million Russians who could be eligible for conscription, one-way tickets out of the country nearly or completely sold out.[270][271] The Ukrainian offensive in the northeast successfully recaptured the majority of Kharkiv Oblast in September. In the course of the southern counteroffensive, Ukraine retook the city of Kherson in November and Russian forces withdrew to the east bank of the Dnieper River.[citation needed]

The invasion was internationally condemned as a war of aggression.[272][273] A United Nations General Assembly resolution demanded a full withdrawal of Russian forces, the International Court of Justice ordered Russia to suspend military operations and the Council of Europe expelled Russia. Many countries imposed new sanctions, which affected the economies of Russia and the world,[274] and provided humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine.[275] In September 2022, Putin signed a law that would punish anyone who resists conscription with a 10-year prison sentence[276] resulting in an international push to allow asylum for Russians fleeing conscription.[277]

As of August 2023, the total number of Russian and Ukrainian soldiers killed or wounded during the Russian invasion of Ukraine was nearly 500,000.[278] More than 10,000 civilians were killed during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[279] According to a declassified US intelligence assessment, as of December 2023, Russia had lost 315,000 of the 360,000 troops that made up Russia's pre-invasion ground force, and 2,200 of the 3,500 tanks.[280]

Between December 2023 and May 2024, Russia was assessed to have increased its drone and missile attacks, firing harder-to-hit weapons, such as ballistic missiles.[281] By the same measure, Ukraine forces were seen to be low on ammunition, particularly the Patriot systems that have been "its best defense against such attacks".[281]

Human rights violations

Violations of human rights and atrocity crimes have both occurred during the war. From 2014 to 2021, there were more than 3,000 civilian casualties, with most occurring in 2014 and 2015.[282] The right of movement was impeded for the inhabitants of the conflict zone.[283] Arbitrary detention was practiced by both sides in the first years of the conflict. It decreased after 2016 in government-held areas, while in the separatist-held ones it continued.[284] Investigations into the abuses committed by both sides made little progress.[285][286]

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russian authorities and armed forces have committed multiple war crimes in the form of deliberate attacks against civilian targets,[287][288] massacres of civilians, torture and rape of women and children,[289][290] and indiscriminate attacks in densely populated areas. After the Russian withdrawal from areas north of Kyiv, overwhelming evidence of war crimes by Russian forces was discovered. In particular, in the town of Bucha, evidence emerged of a massacre of civilians perpetrated by Russian troops, including torture, mutilation, rape, looting and deliberate killings of civilians.[291][292][293] the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (OHCHR) has documented the murder of at least 73 civilians – mostly men, but also women and children – in Bucha.[294] More than 1,200 bodies of civilians were found in the Kyiv region after Russian forces withdrew, some of them summarily executed. There were reports of forced deportations of thousands of civilians, including children, to Russia, mainly from Russian-occupied Mariupol,[295][296] as well as sexual violence, including cases of rape, sexual assault and gang rape,[297] and deliberate killing of Ukrainian civilians by Russian forces.[298] Russia has also systematically attacked Ukrainian medical infrastructure, with the World Health Organization reporting 1,422 attacks as of 21 December 2023.[299]

Ukrainian forces have also been accused of committing various war crimes, including mistreatment of detainees, though on a much smaller scale than Russian forces.[300][301]

In early May 2024, Artem Lysohor, the Head of the Luhansk Regional Military–Civil Administration, announced that since 6 May 2024 mothers giving births in the Russia's controlled part of the Luhansk Oblast hospitals will have to prove that one of the newborn's parents have a Russian citizenship, otherwise they will not be allowed to leave the hospitals with their newborns who may be taken away.[302]

Related issues

Spillover

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023) |

On 19 September 2023, CNN reported that it was "likely" that Ukrainian Special Operations Forces were behind a series of drone strikes and a ground operation directed against the Wagner-backed RSF near Khartoum on 8 September.[303] Kyrylo Budanov, chief of the Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, stated in an interview on 22 September that he could neither deny nor confirm the involvement of Ukraine in the conflict in Sudan,[304] but said that Ukraine would punish Russian war criminals anywhere in the world.[305]

In September and October 2023, a series of fragments were reported found in Romania, a NATO member state, which were suspected to have been the remains of a Russian drone attack near the Romanian border with Ukraine.[306][307]

Gas disputes and Nord Stream sabotage

Until 2014 Ukraine was the main transit route for Russian natural gas sold to Europe, which earned Ukraine about US$3 billion a year in transit fees, making it the country's most lucrative export service.[308] Following Russia's launch of the Nord Stream pipeline, which bypasses Ukraine, gas transit volumes steadily decreased.[308] Following the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War in February 2014, severe tensions extended to the gas sector.[309][310] The subsequent outbreak of war in the Donbas region forced the suspension of a project to develop Ukraine's own shale gas reserves at the Yuzivska gas field, which had been planned as a way to reduce Ukrainian dependence on Russian gas imports.[311] Eventually, the EU commissioner for energy Günther Oettinger was called in to broker a deal securing supplies to Ukraine and transit to the EU.[312]

An explosion damaged a Ukrainian portion of the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast in May 2014. Ukrainian officials blamed Russian terrorists.[313] Another section of the pipeline exploded in the Poltava Oblast on 17 June 2014, one day after Russia limited the supply of gas to Ukrainian customers due to non-payment. Ukraine's Interior Minister Arsen Avakov said the following day that the explosion had been caused by a bomb.[314]

In 2015, Russian state media reported that Russia planned to completely abandon gas supplies to Europe through Ukraine after 2018.[315][316] Russia's state-owned energy giant Gazprom had already substantially reduced the volumes of gas transited across Ukraine, and expressed its intention to reduce the level further by means of transit-diversification pipelines (Turkish Stream, Nord Stream, etc.).[317] Gazprom and Ukraine agreed to a five-year deal on Russian gas transit to Europe at the end of 2019.[318][319]

In 2020, the TurkStream natural gas pipeline running from Russia to Turkey changed the regional gas flows in South-East Europe by diverting the transit through Ukraine and the Trans Balkan Pipeline system.[320][321]

In May 2021, the Biden administration waived Trump's CAATSA sanctions on the company behind Russia's Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Germany.[322][323] Ukrainian President Zelenskyy said he was "surprised" and "disappointed" by Joe Biden's decision.[324] In July 2021, the U.S. urged Ukraine not to criticise a forthcoming agreement with Germany over the pipeline.[325][326]

In July 2021, Biden and German Chancellor Angela Merkel concluded a deal that the U.S. might trigger sanctions if Russia used Nord Stream as a "political weapon". The deal aimed to prevent Poland and Ukraine from being cut off from Russian gas supplies. Ukraine will get a $50 million loan for green technology until 2024 and Germany will set up a billion dollar fund to promote Ukraine's transition to green energy to compensate for the loss of the gas-transit fees. The contract for transiting Russian gas through Ukraine will be prolonged until 2034, if the Russian government agrees.[327][328][329]

In August 2021, Zelenskyy warned that the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline between Russia and Germany was "a dangerous weapon, not only for Ukraine but for the whole of Europe."[330][331] In September 2021, Ukraine's Naftogaz CEO Yuriy Vitrenko accused Russia of using natural gas as a "geopolitical weapon".[332] Vitrenko stated that "A joint statement from the United States and Germany said that if the Kremlin used gas as a weapon, there would be an appropriate response. We are now waiting for the imposition of sanctions on a 100% subsidiary of Gazprom, the operator of Nord Stream 2."[333]

On 26 September 2022, a series of underwater explosions and consequent gas leaks occurred on the Nord Stream 1 (NS1) and Nord Stream 2 (NS2) natural gas pipelines.[334] The investigations by Sweden and Denmark described the explosions as sabotage,[335][336][337][338] and were closed without identifying perpetrators in February 2024.[339][340] The German government refused to publish the preliminary results of its own investigation in July 2024.[341]

Hybrid warfare

The Russo-Ukrainian conflict has also included elements of hybrid warfare using non-traditional means. Cyberwarfare has been used by Russia in operations including successful attacks on the Ukrainian power grid in December 2015 and in December 2016, which was the first successful cyber attack on a power grid,[342] and the Mass hacker supply-chain attack in June 2017, which the US claimed was the largest known cyber attack.[343] In retaliation, Ukrainian operations have included the Surkov Leaks in October 2016 which released 2,337 e-mails in relation to Russian plans for seizing Crimea from Ukraine and fomenting separatist unrest in Donbas.[344] The Russian information war against Ukraine has been another front of hybrid warfare waged by Russia.

A Russian fifth column in Ukraine has also been claimed to exist among the Party of Regions, the Communist Party, the Progressive Socialist Party and the Russian Orthodox Church.[345][346][347]

Russian propaganda and disinformation campaigns

Russian propaganda used "Nazi" allegations for foreign auditory, with "Nazi" term being used the most frequently, followed by "Hitler", with the goal to gather more support for Russian actions in Ukraine. For domestic coverage, Russian media was "almost three times more likely to invoke Bandera than the Nazis".[348] Putin and Russian media have described the government of Ukraine as being led by neo-Nazis persecuting ethnic Russians who are in need of protection by Russia, despite Ukraine's President Zelenskyy being Jewish.[349][350][351] According to journalist Natalia Antonova, "Russia's present-day war of aggression is refashioned by propaganda into a direct continuation of the legacy of the millions of Russian soldiers who died to stop" Nazi Germany in World War II.[352] Ukraine's rejection of the adoption of Russia-initiated General Assembly resolutions on combating the glorification of Nazism, the latest iteration of which is General Assembly Resolution A/C.3/76/L.57/Rev.1 on Combating Glorification of Nazism, Neo-Nazism and other Practices that Contribute to Fueling Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, serve to present Ukraine as a pro-Nazi state, and indeed likely forms the basis for Russia's claims, with the only other state rejecting the adoption of the resolution being the US.[353][354] The Deputy US Representative for ECOSOC describes such resolutions as "thinly veiled attempts to legitimize Russian disinformation campaigns denigrating neighboring nations and promoting the distorted Soviet narrative of much of contemporary European history, using the cynical guise of halting Nazi glorification".[355]

False stories have been used to provoke public outrage during the war. In April 2014, Russian news channels Russia-1 and NTV showed a man saying he was attacked by a fascist Ukrainian gang on one channel and on the other channel saying he was funding the training of right-wing anti-Russia radicals.[357][358] A third segment portrayed the man as a neo-Nazi surgeon.[359] In May 2014, Russia-1 aired a story about Ukrainian atrocities using footage of a 2012 Russian operation in North Caucasus.[360] In the same month, the Russian news network Life presented a 2013 photograph of a wounded child in Syria as a victim of Ukrainian troops who had just retaken Donetsk International Airport.[361]

In June 2014, several Russian state news outlets reported that Ukraine was using white phosphorus using 2004 footage of white phosphorus being used by the United States in Iraq.[360] In July 2014, Channel One Russia broadcast an interview with a woman who said that a 3-year-old boy who spoke Russian was crucified by Ukrainian nationalists in a fictitious square in Sloviansk that turned out to be false.[362][363][358][360]

On 26 February 2020, Vladislav Surkov, who has previously served as Presidential Executive Office's personal adviser of Putin on relationships with Ukraine, gave an interview to Aktualnyie kommentarii where he acknowledged that he was primarily involved with Donbas and Ukraine and claimed that "Ukraine does not exist. There is Ukrainianness, that is, a special brain activity disorder... Such a bloody foreign view. Dusk instead of a country. There is borsch, Bandera, and bandura, but there is no nationality... Forcing them to a fraternal attitude towards Russians is the only method that has proven to be effective in Ukrainianness-oriented activities".[364][365]

In 2022, Russian state media told stories of genocide and mass graves full of ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine. One set of graves outside Luhansk was dug when intense fighting in 2014 cut off the electricity in the local morgue. Amnesty International investigated 2014 Russian claims of mass graves filled with hundreds of bodies and instead found isolated incidents of extrajudicial executions by both sides.[366][351][367]The Russian censorship apparatus Roskomnadzor ordered the country's media to employ information only from Russian state sources or face fines and blocks,[368] and ordered media and schools to describe the war as a "special military operation".[369] On 4 March 2022, Putin signed into law a bill introducing prison sentences of up to 15 years for those who publish "fake news" about the Russian military and its operations,[370] leading to some media outlets to stop reporting on Ukraine.[371] Russia's opposition politician Alexei Navalny said the "monstrosity of lies" in the Russian state media "is unimaginable. And, unfortunately, so is its persuasiveness for those who have no access to alternative information."[372] He tweeted that "warmongers" among Russian state media personalities "should be treated as war criminals. From the editors-in-chief to the talk show hosts to the news editors, [they] should be sanctioned now and tried someday."[373]

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia and former Russian president, publicly wrote that "Ukraine is NOT a country, but artificially collected territories" and that Ukrainian "is NOT a language" but a "mongrel dialect" of Russian.[374] Medvedev has also said that Ukraine should not exist in any form and that Russia will continue to wage war against any independent Ukrainian state.[375] Moreover, Medvedev claimed in July 2023 that Russia would have had to use a nuclear weapon if 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive was a success.[376] According to Medvedev, the "existence of Ukraine is fatally dangerous for Ukrainians and that they will understand that life in a large common state is better than death. Their deaths and the deaths of their loved ones. And the sooner Ukrainians realize this, the better".[377] On 22 February 2024, Medvedev described the future plans of Russia in the Russo-Ukrainian War when he claimed that the Russian Army will go further into Ukraine, taking the southern city of Odesa and may again push on to the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, and stated that "Where should we stop? I don't know".[378] For his claims Medvedev has been described as "Russian rashist (Russian fascist)" by Ukrainian and American media.[379]

NAFO (North Atlantic Fella Organization), a loose cadre of online shitposters vowing to fight Russian disinformation generally identified by cartoon Shiba Inu dogs in social media, gained notoriety after June 2022, in the wake of a Twitter quarrel with Russian diplomat Mikhail Ulyanov.[380]

In February 2024, Putin claimed that the Russo-Ukrainian War has the "elements of a civil war" and that the "Russian people will be reunited", while the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (a branch of the Russian Orthodox Church, which mostly supports the Russian invasion of Ukraine and mandatory publicly pray for military victory over Ukraine) "brings together our souls".[381][382][383] Nevertheless, in the official governmental website of Ukraine it is stated that the Ukrainians and Russians are not "one nation" and that the Ukrainians identify themselves as an independent nation.[384] A poll conducted in April 2022 by "Rating" found that the vast majority (91%) of Ukrainians (excluding the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine) do not support the thesis that "Russians and Ukrainians are one people".[385]

Islamic State claimed responsibility for the 22 March Crocus City Hall attack, a terrorist attack in a music venue in Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast, Russia, and published a corroborating video.[386] Putin and the Russian security service, the FSB, blamed Ukraine for the attack, but did not provide evidence for the attribution.[387] On 3 April 2024, Russia's Defense Ministry announced that "around 16,000 citizens" had signed military contracts in the last 10 days to fight as contract soldiers in the war against Ukraine, with most of them saying they were motivated to "avenge those killed" in the Crocus City Hall attack.[388]

Role of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine

The Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and its hierarch Patriarch Kirill of Moscow have shown their full support of the war against Ukraine.[390] The Russian Orthodox Church officially deems the invasion of Ukraine to be a "holy war".[391] During the World Russian People's Council in March 2024, the Russian Orthodox Church approved a document stating that this "holy war" was to defend "Holy Russia" and to protect the world from globalism and the West, which it said had "fallen into Satanism".[391] The document further stated that all of Ukraine should come under Russia's sphere of influence, and that Ukrainians and Belarusians "should be recognised only as sub-ethnic groups of the Russians".[391] Not one of the approximately 400 Russian Orthodox Church bishops in Russia has spoken out against the war.[392] Patriarch Kirill also issued a prayer for victory in the war.[393]

The role of the Russian Orthodox Church in advancing Putin's war messaging is a vivid illustration of the complex interplay between religion and politics.[394] A Russia expert and fellow of Germany's University of Bremen, told Al Jazeera that the ROC's participation in the war means it “faces the prospect of losing its ‘universal character’ and clout, and of reducing its borders to those of [Russian President Vladimir] Putin's political empire”.[395]

On 27 March 2024 the World Russian People's Council took place in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow where was adopted a "Nakaz" (decree) of the council "The Present and the Future of the Russian World".[396] According to some experts such as the ROC protodeacon Andrei Kurayev it has similarities with the program articles of the German Christians.[397] The decree talks about the so-called "Special Military Operation" in Ukraine, development of the Russian World globally and other issues.[398]

Russia–NATO relations

The conflict has harmed relations between Russia and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a defensive alliance of European and North American states. Russia and NATO had co-operated until Russia annexed Crimea 2014.[399] In his February 2022 speeches justifying the invasion of Ukraine, Putin falsely claimed that NATO was building up military infrastructure in Ukraine and threatening Russia, forcing him to order an invasion.[400] Putin warned that NATO would use Ukraine to launch a surprise attack on Russia.[401] Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov characterized the conflict as a proxy war started by NATO.[402] He said: "We don't think we're at war with NATO ... Unfortunately, NATO believes it is at war with Russia".[403]

NATO says it is not at war with Russia; its official policy is that it does not seek confrontation, but rather its members support Ukraine in "its right to self-defense, as enshrined in the UN Charter".[399] NATO condemned Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine in "the strongest possible terms", and calls it "the biggest security threat in a generation". It led to the deployment of additional NATO units in its eastern member states.[404] Former CIA director Leon Panetta told the ABC that the U.S. is 'without question' involved in a proxy war with Russia.[405] Lawrence Freedman wrote that calling Ukraine a NATO "proxy" wrongly implied that "Ukrainians are only fighting because NATO put them up to it, rather than because of the more obvious reason that they have been subjected to a vicious invasion".[406]

Steven Pifer argues that Russia's own aggressive actions since 2014 have done the most to push Ukraine towards the West and NATO.[407] Russia's invasion led Finland to join NATO, doubling the length of Russia's border with NATO.[408] Putin said that Finland's membership was not a threat, unlike Ukraine's, "but the expansion of military infrastructure into this territory would certainly provoke our response".[409] An article published by the Institute for the Study of War concluded:

"Putin didn't invade Ukraine in 2022 because he feared NATO. He invaded because he believed that NATO was weak, that his efforts to regain control of Ukraine by other means had failed, and that installing a pro-Russian government in Kyiv would be safe and easy. His aim was not to defend Russia against some non-existent threat but rather to expand Russia's power, eradicate Ukraine's statehood, and destroy NATO".[410]

Russian military aircraft flying over the Baltic and Black Seas often do not indicate their position or communicate with air traffic controllers, thus posing a potential risk to civilian airliners. NATO aircraft scrambled many times to track and intercept these aircraft near alliance airspace. The Russian aircraft intercepted never entered NATO airspace, and the interceptions were conducted in a safe and routine manner.[411]

Reactions

Reactions to the Russian annexation of Crimea

Ukrainian response

Interim Ukrainian President Oleksandr Turchynov accused Russia of "provoking a conflict" by backing the seizure of the Crimean parliament building and other government offices on the Crimean peninsula. He compared Russia's military actions to the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, when Russian troops occupied parts of the Republic of Georgia and the breakaway enclaves of Abkhazia and South Ossetia were established under the control of Russian-backed administrations. He called on Putin to withdraw Russian troops from Crimea and stated that Ukraine will "preserve its territory" and "defend its independence".[413] On 1 March, he warned, "Military intervention would be the beginning of war and the end of any relations between Ukraine and Russia."[414] On 1 March, Acting President Oleksandr Turchynov placed the Armed Forces of Ukraine on full alert and combat readiness.[415]

The Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and IDPs was established by Ukrainian government on 20 April 2016 to manage occupied parts of Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea regions affected by Russian military intervention of 2014.[416]

NATO and United States military response

On 4 March 2014, the United States pledged $1 billion in aid to Ukraine.[417] Russia's actions increased tensions in nearby countries historically within its sphere of influence, particularly the Baltic and Moldova. All have large Russian-speaking populations, and Russian troops are stationed in the breakaway Moldovan territory of Transnistria.[418] Some devoted resources to increasing defensive capabilities,[419] and many requested increased support from the U.S. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which they had joined in recent years.[418][419] The conflict "reinvigorated" NATO, which had been created to face the Soviet Union, but had devoted more resources to "expeditionary missions" in recent years.[420]

In addition to diplomatic support in its conflict with Russia, the U.S. provided Ukraine with US$1.5 billion in military aid during the 2010s.[421] In 2018 the U.S. House of Representatives passed a provision blocking any training of Azov Battalion of the Ukrainian National Guard by American forces. In previous years, between 2014 and 2017, the U.S. House of Representatives passed amendments banning support of Azov, but due to pressure from the Pentagon, the amendments were quietly lifted.[422][423][424]

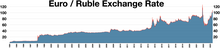

Financial markets

The initial reaction to the escalation of tensions in Crimea caused the Russian and European stock market to tumble.[425]The intervention caused the Swiss franc to climb to a 2-year high against the dollar and 1-year high against the Euro. The Euro and the US dollar both rose, as did the Australian dollar.[426] The Russian stock market declined by more than 10 percent, while the Russian ruble hit all-time lows against the US dollar and the Euro.[427][428][429] The Russian central bank hiked interest rates and intervened in the foreign exchange markets to the tune of $12 billion[clarification needed] to try to stabilize its currency.[426] Prices for wheat and grain rose, with Ukraine being a major exporter of both crops.[430]

Later in March 2014, the reaction of the financial markets to the Crimea annexation was surprisingly mellow, with global financial markets rising immediately after the referendum held in Crimea, one explanation being that the sanctions were already priced in following the earlier Russian incursion.[431]Other observers considered that the positive reaction of the global financial markets on Monday 17 March 2014, after the announcement of sanctions against Russia by the EU and the US, revealed that these sanctions were too weak to hurt Russia.[432]In early August 2014, the German DAX was down by 6 percent for the year, and 11 percent since June, over concerns Russia, Germany's 13th biggest trade partner, would retaliate against sanctions.[433]

Reactions to the war in Donbas

Ukrainian public opinion

A poll of the Ukrainian public, excluding Russian-annexed Crimea, was taken by the International Republican Institute from 12 to 25 September 2014.[434] 89% of those polled opposed 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine. As broken down by region, 78% of those polled from Eastern Ukraine (including Dnipropetrovsk Oblast) opposed said intervention, along with 89% in Southern Ukraine, 93% in Central Ukraine, and 99% in Western Ukraine.[434] As broken down by native language, 79% of Russian speakers and 95% of Ukrainian speakers opposed the intervention. 80% of those polled said the country should remain a unitary country.[434]

A poll of the Crimean public in Russian-annexed Crimea was taken by the Ukrainian branch of Germany's biggest market research organization, GfK, on 16–22 January 2015. According to its results: "Eighty-two percent of those polled said they fully supported Crimea's inclusion in Russia, and another 11 percent expressed partial support. Only 4 percent spoke out against it."[435][436][437]

A joint poll conducted by Levada and the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology from September to October 2020 found that in the breakaway regions controlled by the DPR/LPR, just over half of the respondents wanted to join Russia (either with or without some autonomous status) while less than one-tenth wanted independence and 12% wanted reintegration into Ukraine. It contrasted with respondents in Kyiv-controlled Donbas, where a vast majority felt the separatist regions should be returned to Ukraine.[438] According to results from Levada in January 2022, roughly 70% of those in the breakaway regions said their territories should become part of the Russian Federation.[439]

Russian public opinion

An August 2014 survey by the Levada Centre reported that only 13% of those Russians polled would support the Russian government in an open war with Ukraine.[440] Street protests against the war in Ukraine arose in Russia. Notable protests first occurred in March[441][442] and large protests occurred in September when "tens of thousands" protested the war in Ukraine with a peace march in downtown Moscow on Sunday, 21 September 2014, "under heavy police supervision".[443]

Reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

Ukrainian public opinion

In March 2022, a week after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, 98% of Ukrainians – including 82% of ethnic Russians living in Ukraine – said they did not believe that any part of Ukraine was rightfully part of Russia, according to Lord Ashcroft's polls which did not include Crimea and the separatist-controlled part of Donbas. 97% of Ukrainians said they had an unfavourable view of Russian President Vladimir Putin, with a further 94% saying they had an unfavourable view of the Russian Armed Forces.[444]

At the end of 2021, 75% of Ukrainians said they had a positive attitude toward ordinary Russians, while in May 2022, 82% of Ukrainians said they had a negative attitude toward ordinary Russians.[445]

A Razumkov Centre poll conducted from January 19 to January 25, 2024, found that Russia was the most negatively viewed country in Ukraine, with it being viewed negatively by 95% of Ukrainian respondents. The second, third and fourth most negatively viewed countries were Belarus (87%), Iran (82%) and China (72.5%) respectively. Ukrainian respondents were most positive towards Lithuania (91%), Latvia (90.5%), the UK (90%), Germany (89%), Estonia (89%), Canada (88%) and the US (87%).[446][447]

Russian public opinion

Countries on Russia's "Unfriendly Countries List". The list includes countries that have imposed sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.[448]

An April 2022 survey by the Levada Centre reported that approximately 74% of the Russians polled supported the "special military operation" in Ukraine, suggesting that Russian public opinion has shifted considerably since 2014.[449] According to some sources, a reason many Russians supported the "special military operation" has to do with the propaganda and disinformation.[450][451] In addition, it has been suggested that some respondents did not want to answer pollsters' questions for fear of negative consequences.[452][453] At the end of March, a poll conducted in Russia by the Levada Center concluded the following: When asked why they think the military operation is taking place, respondents said it was to protect and defend civilians, ethnic Russians or Russian speakers in Ukraine (43%), to prevent an attack on Russia (25%), to get rid of nationalists and "denazify" Ukraine (21%), and to incorporate Ukraine or the Donbas region into Russia (3%)."[454] According to polls, the Russian President's rating rose from 71% on the eve of the invasion to 82% in March 2023.[455]

The Kremlin's analysis concluded that public support for the war was broad but not deep, and that most Russians would accept anything Putin would call a victory. In September 2023, the head of the VTsIOM state pollster Valery Fyodorov said in an interview that only 10–15% of Russians actively supported the war, and that "most Russians are not demanding the conquest of Kyiv or Odesa."[456]

In 2023, Oleg Orlov, the chairman of the Board of Human Rights Center "Memorial", claimed that Russia under Vladimir Putin had descended into fascism and that the army is committing "mass murder".[457][458]

United States

On 28 April 2022, US President Joe Biden asked Congress for an additional $33 billion to assist Ukraine, including $20 billion to provide weapons to Ukraine.[460] On 5 May, Ukraine's Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal announced that Ukraine had received more than $12 billion worth of weapons and financial aid from Western countries since the start of Russia's invasion on 24 February.[461] On 21 May 2022, the United States passed legislation providing $40 billion in new military and humanitarian foreign aid to Ukraine, marking a historically large commitment of funds.[462][463] In August 2022, U.S. defense spending to counter the Russian war effort exceeded the first 5 years of war costs in Afghanistan. The Washington Post reported that new U.S. weapons delivered to the Ukrainian war front suggest a closer combat scenario with more casualties.[464] The United States looks to build "enduring strength in Ukraine" with increased arms shipments and a record-breaking $3 billion military aid package.[464]

On 22 April 2022, professor Timothy D. Snyder published an article in The New York Times Magazine where he wrote that "we have tended to overlook the central example of fascism's revival, which is the Putin regime in the Russian Federation".[465] On the wider regime, Snyder writes that "[p]rominent Russian fascists are given access to mass media during wars, including this one. Members of the Russian elite, above all Putin himself, rely increasingly on fascist concepts", and states that "Putin's very justification of the war in Ukraine [...] represents a Christian form of fascism."[465]

On 7 March 2024, American President Joe Biden given the 2024 State of the Union Address where he compared Russia under Vladimir Putin to Adolf Hitler's conquests of Europe.[466]

Russian military suppliers

After expending large amounts of heavy weapons and munitions over months, the Russian Federation received combat drones, loitering munitions, and large amounts of artillery from Iran, deliveries of tanks and other armoured vehicles from Belarus, and reportedly planned to trade for artillery ammunition from North Korea and ballistic missiles from Iran.[468][469][470][471][472]

The U.S. has accused China of providing Russia with technology it needs for high-tech weapons, allegations which China has denied. The U.S. sanctioned a Chinese firm for providing satellite imagery to Russian mercenary forces fighting in Ukraine.[473]

In March 2023, Western nations had pressed the United Arab Emirates to halt re-exports of goods to Russia which had military uses, amidst allegations that the Gulf country exported 158 drones to Russia in 2022.[474] In May 2023, the U.S. accused South Africa of supplying arms to Russia in a covert naval operation,[475] allegations which have been denied by South African president Cyril Ramaphosa.[476]

United Nations

On 25 February 2022, the Security Council failed to adopt a draft resolution which would have "deplored, in the strongest terms, the Russian Federation's aggression" on Ukraine. Of the 15 member states on the Security Council, 11 were in support, whilst three abstained from voting. The draft resolution failed due to a Russian veto.[477][478]

Due to the deadlock, the Security Council passed a resolution to convene the General Assembly for the eleventh emergency special session.[479] On 2 March 2022, the General Assembly voted to deplore "in the strongest possible terms" Russia's aggression against Ukraine by a vote of 141 to 5, with 35 abstentions.[480] The resolution also called for the Russian Federation to "immediately cease its use of force against Ukraine" and "immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces."[480] Only Russia, Belarus, Syria, North Korea and Eritrea voted against the resolution.[481]

On 4 March 2022, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution by a vote of 32 to 2, with 13 abstentions, calling for the withdrawal of Russian troops and Russian-backed armed groups from Ukraine and humanitarian access to people in need. The resolution also established a commission to investigate alleged rights violations committed during Russia's military attack on Ukraine.[482]

In October 2022, the United Nations General Assembly had adopted a resolution condemning the 2022 annexation referendums in Russian-occupied Ukraine with 143 supporting votes, 5 opposing votes (Belarus, North Korea, Nicaragua, Russia, Syria), and 35 abstentions.[483]

Russian strategy

As politics researchers Dominique Arel and Jesse Driscoll write, "The Kremlin sent troops where it did after observing the strategies of Russian-speaking communities within Ukraine. Such communities directly adjoining Russia’s border (Kharkiv and Donbas), and Russia’s redefined border post-Crimea (such as the Donbas city of Mariupol and the oblasts of Kherson and Odesa – close to Transnistria and the ocean) acted with a higher chance of successful separation compared to the heartland areas of Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, or Mykolaiv. The Kremlin waited for either local allies to obtain the backing of the regional parliament or for local armed allies to secure territory first. Russia was responsive and opportunistic."[484]

See also

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic were Russian-controlled puppet states that declared their independence from Ukraine in May 2014. In 2022 they received international recognition from each other, Russia, Syria and North Korea, and some other partially recognised states. On 30 September 2022 Russia declared it had formally annexed both entities.

- ^ There are "some contradictions and inherent problems" regarding the date on which the occupation began.[485] The Ukrainian Government maintains, and the European Court of Human Rights agrees, that Russia controlled Crimea from 27 February 2014,[486] when unmarked Russian special forces took control of its political institutions.[487] The Russian Government later made 27 February "Special Operations Forces Day".[65] In 2015, the Ukrainian parliament officially designated 20 February 2014 as "the beginning of the temporary occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia",[488] citing the date inscribed on the Russian medal "For the Return of Crimea".[489] On that date, Vladimir Konstantinov, then Chairman of the Supreme Council of Crimea, had said the region would be prepared to join Russia.[490] In 2018, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov claimed that the earlier "start date" on the medal was due to a "technical misunderstanding".[491] President Putin stated in a Russian film about the annexation that he ordered the operation to "restore" Crimea to Russia following an all-night emergency meeting on 22–23 February 2014.[485][492]

- ^ Russian: российско-украинская война, romanized: rossiysko-ukrainskaya voyna; Ukrainian: російсько-українська війна, romanized: rosiisko-ukrainska viina.

References

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (6 September 2023). "Ukraine war: Romania reveals Russian drone parts hit its territory". Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (17 March 2024). "Five Takeaways From Putin's Orchestrated Win in Russia". The New York Times.

- ^ "'Terrible toll': Russia's invasion of Ukraine in numbers". Euractiv. 14 February 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Hussain, Murtaza (9 March 2023). "The War in Ukraine Is Just Getting Started". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Budjeryn, Mariana (21 May 2021). "Revisiting Ukraine's Nuclear Past Will Not Help Secure Its Future". Lawfare. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Budjeryn, Mariana. "Issue Brief #3: The Breach: Ukraine's Territorial Integrity and the Budapest Memorandum" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Vasylenko, Volodymyr (15 December 2009). "On assurances without guarantees in a 'shelved document'". The Day. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2022.