Mortar and pestle

Kitchen mortar with pestle inside | |

| Uses | |

|---|---|

| Related items | |

A mortar and pestle is a set of two simple tools used to prepare ingredients or substances by crushing and grinding them into a fine paste or powder in the kitchen, laboratory, and pharmacy. The mortar (/ˈmɔːrtər/) is characteristically a bowl, typically made of hardwood, metal, ceramic, or hard stone such as granite. The pestle (/ˈpɛsəl/, also US: /ˈpɛstəl/) is a blunt, club-shaped object. The substance to be ground, which may be wet or dry, is placed in the mortar where the pestle is pounded, pressed, or rotated into the substance until the desired texture is achieved.

Mortars and pestles have been used in cooking since the Stone Age; today they are typically associated with the pharmacy profession due to their historical use in preparing medicines. They are used in chemistry settings for pulverizing small amounts of chemicals; in arts and cosmetics for pulverizing pigments, binders, and other substances; in ceramics for making grog; in masonry and other types of construction requiring pulverized materials. In cooking, they are typically used to crush spices, to make pesto, and certain cocktails such as the mojito, which requires the gentle crushing of sugar, ice, and mint leaves in the glass with a pestle.

The invention of mortars and pestles seems related to that of quern-stones, which use a similar principle of naturally indented, durable, hard stone bases and mallets of stone or wood to process food and plant materials, clay, or minerals by stamping, crushing, pulverizing and grinding.

A key advantage of the mortar is that it presents a deeper bowl for confining the material to be ground without the waste and spillage that occur with flat grinding stones. Another advantage is that the mortar can be made large enough for a person to stand upright and adjacent to it and use the combined strength of their upper body and the force of gravity for better stamping. Large mortars allow some individuals with several pestles to stamp the material faster and more efficiently. Working over a large mortar that a person can stand next to is physically easier and more ergonomic (by ensuring a better posture of the whole body) than for a small quern, where a person has to crouch and use the uncomfortable, repetitive motion of hand grinding by sliding.

Mortars and pestles predate modern blenders and grinders and can be described as having the function of small, mobile, hand-operated mills that do not require electricity or fuel to operate.

Large wooden mortars and wooden pestles would predate and lead to the invention of butter churns, as domestication of livestock and use of dairy (during the Neolithic) came well after the mortar and pestle. Butter would be churned from cream or milk in a wooden container with a long wooden stick, very like the use of wooden mortars and pestles.

History

[edit]

Mortars and pestles were invented in the Stone Age when humans found that processing food and various other materials by grinding and crushing into smaller particles allowed for improved use and various advantages. Hard grains could be cooked and digested more easily if ground first, grinding potsherds into grog would vastly improve fired clay, and larger objects such as blocks of salt would be much easier to handle and use. Various stone mortars and pestles have been found, while wooden or clay ones would perish much more easily over time.

Scientists have found ancient mortars and pestles in Southwest Asia that date back to approximately 35000 BC.[1]

Stone mortars and pestles have also been used by the Kebaran culture (the Levant with Sinai) from 22000 to 18000 BC to crush grains and other plant material. The Kebaran mortars that have been found are sculpted, slightly conical bowls of porous stone, and the pestles are made of a smoother type of stone.[2]

Another Stone Age example is the rock mortars in the Raqefet Cave in Israel, which are natural cavities in the cave floors, used by Late Natufians around 10000 BC to grind cereals for brewing beer in the cavities. These rock mortars are large enough for a person to stand upright by them and crush the cereals inside the cavity with a long wooden pestle.[3][4]

Ancient Africans, Sumerians, Egyptians, Thai, Laos People, Polynesians, Native Americans, Chinese, Indians, Greeks, Celts, and countless other people used mortars and pestles for processing materials and substances for cooking, arts, cosmetics, simple chemicals, ceramics and medicine.

Since the 14th century, bronze mortars became more popular than stone ones, especially for use in alchemy and early chemistry. Bronze mortars would become more elaborate than stone ones, had the advantage to be harder, and were easily cast with handles, knobs for handling, and spouts for easier pouring. However, the big disadvantage was that bronze would react with acids and other chemicals and corrode easily. Since the late 17th century, glazed porcelain mortars became very useful, since they would not be damaged by chemicals and would be easy to clean.[5]

Etymology

[edit]The English word mortar derives from Middle English morter, from old French mortier, from classical Latin mortarium, meaning, among several other usages, "receptacle for pounding" and "product of grinding or pounding"; perhaps related to Sanskrit "mrnati" - to crush, to bruise.[6]

The classical Latin pistillum, meaning "pounder", led to the English pestle. Stemming from the pistillum, the word pesto in Italian cuisine means created with the pestle.

The Roman poet Juvenal applied both mortarium and pistillum to articles used in the preparation of drugs, reflecting the early use of the mortar and pestle as a symbol of a pharmacist or apothecary.[7]

Mortar as a synonym for cement in masonry came from the use of mortars and pestles to grind the materials for creating cement. The short bombard cannon was called "mortar" in French because the first versions of these cannons looked like big metal mortars of the Medieval Ages and they required to be filled with gunpowder, like a mortar would be full of powdered material. [8]

The mortar and pestle in culture and symbols

[edit]

The antiquity of the mortar and pestle is well documented in early writing, such as the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus of around 1550 BC (the oldest preserved piece of medical literature) and the Old Testament (Numbers 11:8 and Proverbs 27:22).[9]

In Indian mythology, Samudra Manthan from Bhagavata Purana creates amrita, the nectar of immortality, by churning the ocean with a pestle.

Since medieval times, mortars would be placed or carved on the gravestones of pharmacists and doctors.

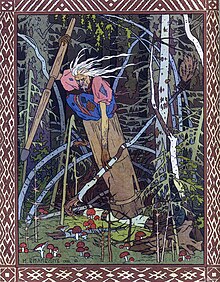

In Russian and Eastern European folklore, Baba Yaga is described and pictured as flying through the forest standing inside a large wooden mortar (stupa), holding the long wooden pestle in one hand to remove obstacles in front of her, and using the broom in her other hand to sweep and remove her traces behind her. This seems as a trace of some ancient rituals connecting the witch symbols of Baba Yaga with the use of mortars in alchemy, pharmacy, and early chemistry, which were all seen as magic by uneducated people in the Medieval Ages.

In various Asian mythologies and folklores, there is a common theme of a Moon rabbit, making use of a mortar and pestle to process the ingredients for the Elixir of life (or rice for making mochi).

Modern pharmacies, especially in Germany, still use mortars and pestles as logos.

Uses

[edit]Medicine

[edit]

Mortars and pestles were traditionally used in pharmacies to crush various ingredients before preparing an extemporaneous prescription. The mortar and pestle, with the Rod of Asclepius, the Green Cross, and others, is one of the most pervasive symbols of pharmacology,[10] along with the show globe.

For pharmaceutical use, the mortar and the head of the pestle are usually made of porcelain, while the handle of the pestle is made of wood. This is known as a Wedgwood mortar and pestle and originated in 1759. Today the act of mixing ingredients or reducing the particle size is known as trituration.

Mortars and pestles are also used as drug paraphernalia to grind up pills to speed up absorption when they are ingested, or in preparation for insufflation. To finely ground drugs, not available in the liquid dosage form are used also if patients need artificial nutrition such as parenteral nutrition or by nasogastric tube.

Food preparation

[edit]

Mortars are also used in cooking to prepare wet or oily ingredients such as guacamole, hummus, and pesto (which derives its name from the pestle pounding), as well as grinding spices into powder. The molcajete, a version used by pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican cultures including the Aztec and Maya, stretching back several thousand years, is made of basalt and is used widely in Mexican cooking. Other Native American nations use mortars carved into the bedrock to grind acorns and other nuts. Many such depressions can be found in their territories.

In Japan, very large mortars are used with wooden mallets to prepare mochi. A regular-sized Japanese mortar and pestle are called a suribachi and surikogi, respectively. Granite mortars and pestles are used in Southeast Asia,[11][12] as well as Pakistan and India. In India, it is used extensively to make spice mixtures for various delicacies as well as day-to-day dishes. With the advent of motorized grinders, the use of the mortar and pestle has decreased. It is traditional in various Hindu ceremonies (such as weddings, and upanayanam) to crush turmeric in these mortars.

In Malay, it is known as batu lesung. Large stone mortars, with long (2–3 foot) wood pestles were used in West Asia to grind meat for a type of meatloaf, or kibbeh, as well as the hummus variety known as masabcha. In Indonesia mortar is known as Cobek or Tjobek and pestle is known as Ulekan or Oelekan. The chobek is shaped like a deep saucer or plate. The ulekan is either pistol-shaped or ovoid. It is often used to make fresh sambal, a spicy chili condiment, hence the sambal ulek/oelek denotes its process using pestle. It is also used to grind peanuts and other ingredients to make peanut sauce for gado-gado.

Husking and dehulling

[edit]

Large mortars and pestles are still commonly used in developing countries to husk and dehull grain. These are usually made of wood, and operated by one or more persons.

In the Philippines, mortar and pestles are specifically associated with de-husking rice. A notable traditional mortar and pestle is the boat-shaped bangkang pinawa or bangkang pangpinawa, literally "boat (bangka) for unpolished rice", usually carved from a block of molave or other hardwood. It is pounded by two or three people. The name for the mortar, lusong, is the origin of the name of the largest island in the Philippines, Luzon.[13]

Large wooden mortars and pestles have been used to hull grain in West Africa for centuries. When enslaved Africans were brought to the Americas, they brought this technology—and knowledge of how to use it—with them. During the Middle Passage, some slave ships carried un-hulled rice, and enslaved African women were tasked with using mortars and pestles to prepare it for consumption. In both colonial North and South America, rice continued to be primarily milled by hand in this way until around the mid-1700s when mechanical mills became more widespread.[14]

Material

[edit]Good mortar and pestle-making materials must be hard enough to crush the substance rather than be worn away by it. They cannot be too brittle either, or they will break during the pounding and grinding. The material should also be cohesive so that small bits of the mortar or pestle do not mix in with the ingredients. Smooth and non-porous materials are chosen that will not absorb or trap the substances being ground.[15]

In food preparation, a rough or absorbent material may cause the strong flavor of a past ingredient to be tasted in food prepared later. Also, the food particles left in the mortar and on the pestle may support the growth of microorganisms. When dealing with medications, the previously prepared drugs may interact or mix, contaminating the currently used ingredients.

Rough ceramic mortar and pestle sets can be used to reduce substances to very fine powders, but stain easily and are brittle. Porcelain mortars are sometimes conditioned for use by grinding some sand to give them a rougher surface which helps to reduce the particle size. Glass mortars and pestles are fragile, but stain-resistant and suitable for use with liquids. However, they do not grind as finely as the ceramic type.

Other materials used include stone, often marble or agate, wood (which is highly absorbent), bamboo, iron, steel, brass, and basalt. Mortar and pestle sets made from the wood of old grape vines have proved reliable for grinding salt and pepper at the dinner table. Uncooked rice is sometimes ground in mortars to clean them. This process must be repeated until the rice comes out completely white. Some stones, such as molcajete, need to be seasoned first before use. Metal mortars are kept lightly oiled.

Automatic mortar grinder

[edit]Since the results obtained with hand grinding are not easily reproducible, most laboratories use automatic mortar grinders. Grinding time and pressure of the mortar can be adjusted and fixed, saving time and labor.

The first automatic Mortar Grinder was invented by F. Kurt Retsch in 1923 and named the "Retschmill" after him.[16]

Advantages

[edit]The use of mortar and pestle, pestling, offers the advantage that the substance is crushed with low energy so that the substance will not warm up.

Gallery

[edit]-

Mortar and pestle made from bronze alloy, Greece.

-

Mitmita made in Ethiopia

-

Tjobek, the Indonesian word in Dutch spelling for mortars and pestles

-

A traditional Nepali mortar and pestle

-

Molcajete y tejolote, Mexico

-

A Lao‑style mortar and pestle

-

Mortar used to pulverize plant material

-

A wooden mortar and pestle

-

A stone mortar unearthed at archaeological site in Israel

See also

[edit]- Cupstone

- Dheki

- Dolly pot

- Makitra

- Metate

- Millstone

- Muddler

- Molcajete

- Oralu kallu

- Quern-stone

- Stone and muller

- Suribachi and surikogi

- Usu and Kine, large pestle and mortar used in the production of mochi

- Yagen

- Household Stone tools in Karnataka

- The Knight of the Burning Pestle

References

[edit]- ^ Wright, K. (1991). "The Origins and Development of Ground Stone Assemblages in Late Pleistocene Southwest Asia" (PDF). Paléorient. 17 (1): 19–45. doi:10.3406/paleo.1991.4537. JSTOR 41492435.

- ^ Mellaart, James (1976), Neolithic of the Near East (Macmillan Publishers)

- ^ Metheny, Karen Bescherer; Beaudry, Mary C. (2015). Archaeology of Food: An Encyclopedia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 46. ISBN 9780759123663.

- ^ Birch, Suzanne E. Pilaar (2018). Multispecies Archaeology. Routledge. p. 546. ISBN 9781317480648.

- ^ "History of Mortars". 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Sanskrit root of Mortar".

- ^ Satire VII line 170: et quae iam ueteres sanant mortaria caecos. (and the mortars that cure old blind men)

- ^ "Etymology of Mortar".

- ^ "www.usip.edu The mortar and pestle from the renaissance to the present" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-19. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Symbols". studylib.net. Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Sukphisit, Suthon (2019-03-24). "The enduring symbol of Thai cuisine". Bangkok Post. No. B. Magazine. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- ^ "The Mortar and Pestle in Thai Cuisine". Temple of Thai. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ Foreman, John (1892). The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnographical, Social and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago, Embracing the Whole Period of Spanish Rule. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Carney, Judith A. (January 25, 2007). "With grains in her hair: rice in colonial Brazil". Slavery & Abolition. 25 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/0144039042000220900. S2CID 3490844.

- ^ "Kitchen Essentials for Southeast Asian Cooking Basic tools and equipment for cooking Southeast Asian food". about food. Section 2. Mortar and Pestle to Make the Best Spice Pastes. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "About Us: History". Retsch GmbH. Retrieved 19 January 2020.