Wage slavery

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism

(For and against) |

|---|

Wage slavery is a term used to criticize exploitation of labor by business, by keeping wages low or stagnant in order to maximize profits. The situation of wage slavery can be loosely defined as a person's dependence on wages (or a salary) for their livelihood, especially when wages are low, treatment and conditions are poor, and there are few chances of upward mobility.[1][2]

The term is often used by critics of wage-based employment to criticize the exploitation of labor and social stratification, with the former seen primarily as unequal bargaining power between labor and capital, particularly when workers are paid comparatively low wages, such as in sweatshops,[3] and the latter is described as a lack of workers' self-management, fulfilling job choices and leisure in an economy.[4][5][6] The criticism of social stratification covers a wider range of employment choices bound by the pressures of a hierarchical society to perform otherwise unfulfilling work that deprives humans of their "species character"[7] not only under threat of extreme poverty and starvation, but also of social stigma and status diminution.[8][9][4] Historically, many socialist organisations and activists have espoused workers' self-management or worker cooperatives as possible alternatives to wage labor.[5][10]

Similarities between wage labor and slavery were noted as early as Cicero in Ancient Rome, such as in De Officiis.[11] With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, thinkers such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Karl Marx elaborated the comparison between wage labor and slavery, and engaged in critique of work[12][13] while Luddites emphasized the dehumanization brought about by machines. The introduction of wage labor in 18th-century Britain was met with resistance, giving rise to the principles of syndicalism and anarchism.[14][15][10][16]

Before the American Civil War, Southern defenders of keeping African Americans in slavery invoked the concept of wage slavery to favourably compare the condition of their slaves to workers in the North.[17][18] The United States abolished most forms of slavery after the Civil War, but labor union activists found the metaphor useful – according to historian Lawrence Glickman, in the 1870s through the 1890s "[r]eferences abounded in the labor press, and it is hard to find a speech by a labor leader without the phrase".[19]

History[edit]

The view that working for wages is akin to slavery dates back to the ancient world.[21] In ancient Rome, Cicero wrote that "the very wage [wage labourers] receive is a pledge of their slavery".[11]

In 1763, the French journalist Simon Linguet published an influential description of wage slavery:[13]

The slave was precious to his master because of the money he had cost him ... They were worth at least as much as they could be sold for in the market ... It is the impossibility of living by any other means that compels our farm labourers to till the soil whose fruits they will not eat and our masons to construct buildings in which they will not live ... It is want that compels them to go down on their knees to the rich man in order to get from him permission to enrich him ... what effective gain [has] the suppression of slavery brought [him ?] He is free, you say. Ah! That is his misfortune ... These men ... [have] the most terrible, the most imperious of masters, that is, need. ... They must therefore find someone to hire them, or die of hunger. Is that to be free?

The view that wage work has substantial similarities with chattel slavery was actively put forward in the late 18th and 19th centuries by defenders of chattel slavery (most notably in the Southern states of the United States) and by opponents of capitalism (who were also critics of chattel slavery).[9][22] Some defenders of slavery, mainly from the Southern slave states, argued that Northern workers were "free but in name – the slaves of endless toil" and that their slaves were better off.[23][24] This contention has been partly corroborated by some modern studies that indicate slaves' material conditions in the 19th century were "better than what was typically available to free urban laborers at the time".[25][26] In this period, Henry David Thoreau wrote that "[i]t is hard to have a Southern overseer; it is worse to have a Northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of yourself."[27]

Abolitionists in the United States criticized the analogy as spurious.[28] They argued that wage workers were "neither wronged nor oppressed".[29] Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans argued that the condition of wage workers was different from slavery as long as laborers were likely to develop the opportunity to work for themselves, achieving self-employment.[30] The abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass initially declared "now I am my own master", upon taking a paying job.[31] However, later in life he concluded to the contrary, saying "experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other".[32][33] Douglass went on to speak about these conditions as arising from the unequal bargaining power between the ownership/capitalist class and the non-ownership/laborer class within a compulsory monetary market:

No more crafty and effective devise for defrauding the southern laborers could be adopted than the one that substitutes orders upon shopkeepers for currency in payment of wages. It has the merit of a show of honesty, while it puts the laborer completely at the mercy of the land-owner and the shopkeeper.[34]

Self-employment became less common as the artisan tradition slowly disappeared in the later part of the 19th century.[5] In 1869, The New York Times described the system of wage labor as "a system of slavery as absolute if not as degrading as that which lately prevailed at the South".[30] E. P. Thompson notes that for British workers at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, the "gap in status between a 'servant,' a hired wage-laborer subject to the orders and discipline of the master, and an artisan, who might 'come and go' as he pleased, was wide enough for men to shed blood rather than allow themselves to be pushed from one side to the other. And, in the value system of the community, those who resisted degradation were in the right".[14] A "Member of the Builders' Union" in the 1830s argued that the trade unions "will not only strike for less work, and more wages, but will ultimately abolish wages, become their own masters and work for each other; labor and capital will no longer be separate but will be indissolubly joined together in the hands of workmen and work-women".[15] This perspective inspired the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (UK) of 1834 which had the "two-fold purpose of syndicalist unions – the protection of the workers under the existing system and the formation of the nuclei of the future society" when the unions "take over the whole industry of the country".[10] William Lazonick, summarized:

Research has shown, that the 'free-born Englishman' of the eighteenth century – even those who, by force of circumstance, had to submit to agricultural wage labour – tenaciously resisted entry into the capitalist workshop.[16]

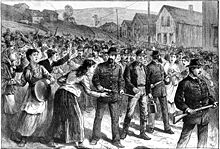

The use of the term "wage slave" by labor organizations may originate from the labor protests of the Lowell mill girls in 1836.[35] The imagery of wage slavery was widely used by labor organizations during the mid-19th century to object to the lack of workers' self-management. However, it was gradually replaced by the more neutral term "wage work" towards the end of the 19th century as labor organizations shifted their focus to raising wages.[5] Karl Marx described capitalist society as infringing on individual autonomy because it is based on a materialistic and commodified concept of the body and its liberty (i.e. as something that is sold, rented, or alienated in a class society). According to Friedrich Engels:[36][37]

The slave is sold once and for all; the proletarian must sell himself daily and hourly. The individual slave, property of one master, is assured an existence, however miserable it may be, because of the master's interest. The individual proletarian, property as it were of the entire bourgeois class which buys his labor only when someone has need of it, has no secure existence.

Similarities of wage work with slavery[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Critics of wage work have drawn several similarities between wage work and slavery:

- Since the chattel slave is property, his value to an owner is in some ways higher than that of a worker who may quit, be fired or replaced. The chattel slave's owner has made a greater investment in terms of the money paid for the slave. For this reason, in times of recession chattel slaves could not be fired like wage laborers. A "wage slave" could also be harmed at no (or less) cost. American chattel-slaves in the 19th century had improved their standard of living from the 18th century[25] and – according to historians Fogel and Engerman – plantation records show that slaves worked less, were better fed and whipped only occasionally – their material conditions in the 19th century being "better than what was typically available to free urban laborers at the time".[26] This was partially due to slave psychological strategies under an economic system different from capitalist wage-slavery. According to Mark Michael Smith of the Economic History Society, "although intrusive and oppressive, paternalism, the way masters employed it, and the methods slaves used to manipulate it, rendered slaveholders' attempts to institute capitalistic work regimens on their plantation ineffective and so allowed slaves to carve out a degree of autonomy".[38]

- Unlike a chattel slave, a wage laborer can (barring unemployment or lack of job offers) choose between employers, but those employers usually constitute a minority of owners in the population for which the wage laborer must work while attempts to implement workers' control on employers' businesses may be considered an act of theft or insubordination and thus be met with violence, imprisonment or other legal and social measures. The wage laborer's starkest choice is to work for an employer or to face poverty or starvation. If a chattel slave refuses to work, a number of punishments are also available; from beatings to food deprivation – although economically rational slave-owners practiced positive reinforcement to achieve best results and before losing their investment by killing an expensive slave.[39][40]

- Historically, the range of occupations and status positions held by chattel slaves has been nearly as broad as that held by free persons, indicating some similarities between chattel slavery and wage slavery as well.[41]

- Like chattel slavery, wage slavery does not stem from some immutable "human nature", but represents a "specific response to material and historical conditions" that "reproduce[s] the inhabitants, the social relations... the ideas... [and] the social form of daily life".[42]

- Similarities became blurred when proponents of wage labor won the American Civil War of 1861–1865, in which they competed for legitimacy with defenders of chattel slavery. Each side presented an over-positive assessment of their own system while denigrating the opponent.[8][28][29]

According to American anarcho-syndicalist philosopher Noam Chomsky, workers themselves noticed the similarities between chattel and wage slavery. Chomsky noted that the 19th-century Lowell mill girls, without any reported knowledge of European Marxism or anarchism, condemned the "degradation and subordination" of the newly emerging industrial system and the "new spirit of the age: gain wealth, forgetting all but self", maintaining that "those who work in the mills should own them".[43][44] They expressed their concerns in a protest song during their 1836 strike:[45]

Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

That I cannot be a slave.

Defenses of both wage labor and chattel slavery in the literature have linked the subjection of man to man with the subjection of man to nature – arguing that hierarchy and a social system's particular relations of production represent human nature and are no more coercive than the reality of life itself. According to this narrative, any well-intentioned attempt to fundamentally change the status quo is naively utopian and will result in more oppressive conditions.[46] Bosses in both of these long-lasting systems argued that their respective systems created a lot of wealth and prosperity. In some sense, both did create jobs, and their investment entailed risk. For example, slave-owners risked losing money by buying chattel slaves who later became ill or died; while bosses risked losing money by hiring workers (wage slaves) to make products that did not sell well on the market. Marginally, both chattel and wage slaves may become bosses; sometimes by working hard. The "rags to riches" story occasionally comes to pass in capitalism; the "slave to master" story occurred in places like colonial Brazil, where slaves could buy their own freedom and become business owners, self-employed, or slave-owners themselves.[47] Thus critics of the concept of wage slavery do not regard social mobility, or the hard work and risk that it may entail, as a redeeming factor.[48]

Anthropologist David Graeber has noted that historically the first wage-labor contracts we know about – whether in ancient Greece or Rome, or in the Malay or Swahili city-states in the Indian Ocean – were in fact contracts for the rental of chattel slaves (usually the owner would receive a share of the money and the slaves another, with which to maintain their living expenses). According to Graeber, such arrangements were quite common in New World slavery as well, whether in the United States or in Brazil. C. L. R. James (1901–1989) argued that most of the techniques of human organization employed on factory workers during the Industrial Revolution first developed on slave plantations.[49] Subsequent work "traces the innovations of modern management to the slave plantation".[50]

Changes in the use of the term[edit]

At the end of the 19th century, North American labor rhetoric turned towards consumerist and economics-based politics, from its previously radical, producerist vision. Whereas labor organizations once referred to powerless disenfranchisement from the rise of industrial capitalism as "wage slavery", the phrase had fallen out of favor by 1890 as those organizations adopted pragmatic politics and phrases like "wage work".[51] American producerist labor politics emphasized the control of production conditions as being the guarantor of self-reliant, personal freedom. As factories began to bring artisans in-house by 1880, wage dependence replaced wage freedom as standard for skilled, unskilled, and unionized workers alike.[52]

As Hallgrimsdottir and Benoit point out:

[I]ncreased centralization of production ... declining wages ... [an] expanding ... labor pool ... intensifying competition, and ... [t]he loss of competence and independence experienced by skilled labor" meant that "a critique that referred to all [wage] work as slavery and avoided demands for wage concessions in favor of supporting the creation of the producerist republic (by diverting strike funds towards funding ... co-operatives, for example) was far less compelling than one that identified the specific conditions of slavery as low wages

— Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit 2007, pp. 1397, 1404, 1402

In more general English-language usage, the phrase "wage slavery" and its variants became more frequent in the 20th century.[53]

Treatment in various economic systems[edit]

Some anti-capitalist thinkers claim that the elite maintain wage slavery and a divided working class through their influence over the media and entertainment industry,[54][55] educational institutions, unjust laws, nationalist and corporate propaganda, pressures and incentives to internalize values serviceable to the power structure, state violence, fear of unemployment, and a historical legacy of exploitation and profit accumulation/transfer under prior systems, which shaped the development of economic theory. Adam Smith noted that employers often conspire together to keep wages low and have the upper hand in conflicts between workers and employers:

The interest of the dealers ... in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public... [They] have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public ... We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combinations of masters, though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labor above their actual rate ... It is not, however, difficult to foresee which of the two parties must, upon all ordinary occasions, have the advantage in the dispute, and force the other into a compliance with their terms.

Capitalism[edit]

The concept of wage slavery could conceivably be traced back to pre-capitalist figures like Gerrard Winstanley from the radical Christian Diggers movement in England, who wrote in his 1649 pamphlet, The New Law of Righteousness, that there "shall be no buying or selling, no fairs nor markets, but the whole earth shall be a common treasury for every man" and "there shall be none Lord over others, but every one shall be a Lord of himself".[57]

Aristotle stated that "the citizens must not live a mechanic or a mercantile life (for such a life is ignoble and inimical to virtue), nor yet must those who are to be citizens in the best state be tillers of the soil (for leisure is needed both for the development of virtue and for active participation in politics)",[58] often paraphrased as "all paid jobs absorb and degrade the mind".[59] Cicero wrote in 44 BC that "vulgar are the means of livelihood of all hired workmen whom we pay for mere manual labour, not for artistic skill; for in their case the very wage they receive is a pledge of their slavery".[11] Somewhat similar criticisms have also been expressed by some proponents of liberalism, like Silvio Gesell and Thomas Paine;[60] Henry George, who inspired the economic philosophy known as Georgism;[9] and the Distributist school of thought within the Catholic Church.

To Karl Marx and anarchist thinkers like Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin, wage slavery was a class condition in place due to the existence of private property and the state. This class situation rested primarily on:

- The existence of property not intended for active use;

- The concentration of ownership in few hands;

- The lack of direct access by workers to the means of production and consumption goods; and

- The perpetuation of a reserve army of unemployed workers.

And secondarily on:

- The waste of workers' efforts and resources on producing useless luxuries;

- The waste of goods so that their price may remain high; and

- The waste of all those who sit between the producer and consumer, taking their own shares at each stage without actually contributing to the production of goods, i.e. the middle man.

Fascism[edit]

Fascist economic policies were more hostile to independent trade unions than modern economies in Europe or the United States.[61] Fascism was more widely accepted in the 1920s and 1930s, and foreign corporate investment (notably from the United States) in Germany increased after the fascists took power.[62][63]

Fascism has been perceived by some notable critics, like Buenaventura Durruti, to be a last resort weapon of the privileged to ensure the maintenance of wage slavery:

No government fights fascism to destroy it. When the bourgeoisie sees that power is slipping out of its hands, it brings up fascism to hold onto their privileges.[64]

Psychological effects[edit]

According to Noam Chomsky, analysis of the psychological implications of wage slavery goes back to the Enlightenment era. In his 1791 book The Limits of State Action, classical liberal thinker Wilhelm von Humboldt explained how "whatever does not spring from a man's free choice, or is only the result of instruction and guidance, does not enter into his very nature; he does not perform it with truly human energies, but merely with mechanical exactness" and so when the laborer works under external control, "we may admire what he does, but we despise what he is".[65] Because they explore human authority and obedience, both the Milgram and Stanford experiments have been found useful in the psychological study of wage-based workplace relations.[66]

Self-identity problems and stress[edit]

According to research,[67] modern work provides people with a sense of personal and social identity that is tied to:

- The particular work role, even if unfulfilling; and

- The social role it entails e.g. family bread-winning, friendship forming and so on.

Thus job loss entails the loss of this identity.[67]

Erich Fromm argued that if a person perceives himself as being what he owns, then when that person loses (or even thinks of losing) what he "owns" (e.g. the good looks or sharp mind that allow him to sell his labor for high wages) a fear of loss may create anxiety and authoritarian tendencies because that person's sense of identity is threatened. In contrast, when a person's sense of self is based on what he experiences in a "state of being" with a less materialistic regard for what he once had and lost, or may lose, then less authoritarian tendencies prevail. In his view, the state of being flourishes under a worker-managed workplace and economy, whereas self-ownership entails a materialistic notion of self, created to rationalize the lack of worker control that would allow for a state of being.[68]

Investigative journalist Robert Kuttner analyzed the work of public-health scholars Jeffrey Johnson and Ellen Hall about modern conditions of work and concludes that "to be in a life situation where one experiences relentless demands by others, over which one has relatively little control, is to be at risk of poor health, physically as well as mentally". Under wage labor, "a relatively small elite demands and gets empowerment, self-actualization, autonomy, and other work satisfaction that partially compensate for long hours" while "epidemiological data confirm that lower-paid, lower-status workers are more likely to experience the most clinically damaging forms of stress, in part because they have less control over their work".[69]

Wage slavery and the educational system that precedes it "implies power held by the leader. Without power the leader is inept. The possession of power inevitably leads to corruption ... in spite of ... good intentions ... [Leadership means] power of initiative, this sense of responsibility, the self-respect which comes from expressed manhood, is taken from the men, and consolidated in the leader. The sum of their initiative, their responsibility, their self-respect becomes his ... [and the] order and system he maintains is based upon the suppression of the men, from being independent thinkers into being 'the men' ... In a word, he is compelled to become an autocrat and a foe to democracy". For the "leader", such marginalisation can be beneficial, for a leader "sees no need for any high level of intelligence in the rank and file, except to applaud his actions. Indeed such intelligence from his point of view, by breeding criticism and opposition, is an obstacle and causes confusion".[70] Wage slavery "implies erosion of the human personality ... [because] some men submit to the will of others, arousing in these instincts which predispose them to cruelty and indifference in the face of the suffering of their fellows".[71]

Psychological control[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Higher wages[edit]

In 19th-century discussions of labor relations, it was normally assumed that the threat of starvation forced those without property to work for wages. Proponents of the view that modern forms of employment constitute wage slavery, even when workers appear to have a range of available alternatives, have attributed its perpetuation to a variety of social factors that maintain the hegemony of the employer class.[42][72]

In an account of the Lowell mill girls, Harriet Hanson Robinson wrote that generously high wages were offered to overcome the degrading nature of the work:

At the time the Lowell cotton mills were started the caste of the factory girl was the lowest among the employments of women. ... She was represented as subjected to influences that must destroy her purity and selfrespect. In the eyes of her overseer she was but a brute, a slave, to be beaten, pinched and pushed about. It was to overcome this prejudice that such high wages had been offered to women that they might be induced to become millgirls, in spite of the opprobrium that still clung to this degrading occupation.[73]

In his book Disciplined Minds, Jeff Schmidt points out that professionals are trusted to run organizations in the interests of their employers. Because employers cannot be on hand to manage every decision, professionals are trained to "ensure that each and every detail of their work favors the right interests–or skewers the disfavored ones" in the absence of overt control:

The resulting professional is an obedient thinker, an intellectual property whom employers can trust to experiment, theorize, innovate and create safely within the confines of an assigned ideology.[74]

Parecon (participatory economics) theory posits a social class "between labor and capital" of higher paid professionals such as "doctors, lawyers, engineers, managers and others" who monopolize empowering labor and constitute a class above wage laborers who do mostly "obedient, rote work".[75]

Lower wages[edit]

The terms "employee" or "worker" have often been replaced by "associate" or "partner". This plays up the allegedly voluntary nature of the interaction while playing down the subordinate status of the wage laborer as well as the worker-boss class distinction emphasized by labor movements. Billboards as well as television, Internet and newspaper advertisements consistently show low-wage workers with smiles on their faces, appearing happy.[76]

Job interviews and other data on requirements for lower skilled workers in developed countries – particularly in the growing service sector – indicate that the more workers depend on low wages and the less skilled or desirable their job is, the more employers screen for workers without better employment options and expect them to feign unremunerative motivation.[77] Such screening and feigning may not only contribute to the positive self-image of the employer as someone granting desirable employment, but also signal wage-dependence by indicating the employee's willingness to feign, which in turn may discourage the dissatisfaction normally associated with job-switching or union activity.[77]

At the same time, employers in the service industry have justified unstable, part-time employment and low wages by playing down the importance of service jobs for the lives of the wage laborers (e.g. just temporary before finding something better, student summer jobs and the like).[78][79]

In the early 20th century, "scientific methods of strikebreaking"[80] were devised – employing a variety of tactics that emphasized how strikes undermined "harmony" and "Americanism".[81]

Workers' self-management[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchist communism |

|---|

|

Some social activists objecting to the market system or price system of wage working historically have considered syndicalism, worker cooperatives, workers' self-management and workers' control as possible alternatives to the current wage system.[4][5][6][10]

Labor and government[edit]

The American philosopher John Dewey believed that until "industrial feudalism" is replaced by "industrial democracy", politics will be "the shadow cast on society by big business".[82] Thomas Ferguson has postulated in his investment theory of party competition that the undemocratic nature of economic institutions under capitalism causes elections to become occasions when blocs of investors coalesce and compete to control the state.[83]

Noam Chomsky has argued that political theory tends to blur the 'elite' function of government:

Modern political theory stresses Madison's belief that "in a just and a free government the rights both of property and of persons ought to be effectually guarded." But in this case too it is useful to look at the doctrine more carefully. There are no rights of property, only rights to property that is, rights of persons with property,... In representative democracy, as in, say, the United States or Great Britain [...] there is a monopoly of power centralized in the state, and secondly – and critically – [...] the representative democracy is limited to the political sphere and in no serious way encroaches on the economic sphere [...] That is, as long as individuals are compelled to rent themselves on the market to those who are willing to hire them, as long as their role in production is simply that of ancillary tools, then there are striking elements of coercion and oppression that make talk of democracy very limited, if even meaningful.[84]

In this regard, Chomsky has used Bakunin's theories about an "instinct for freedom",[85] the militant history of labor movements, Kropotkin's mutual aid evolutionary principle of survival and Marc Hauser's theories supporting an innate and universal moral faculty,[86] to explain the incompatibility of oppression with certain aspects of human nature.[87][88]

Influence on environmental degradation[edit]

Loyola University philosophy professor John Clark and libertarian socialist philosopher Murray Bookchin have criticized the system of wage labor for encouraging environmental destruction, arguing that a self-managed industrial society would better manage the environment. Like other anarchists,[89] they attribute much of the Industrial Revolution's pollution to the "hierarchical" and "competitive" economic relations accompanying it.[90]

Employment contracts[edit]

Some criticize wage slavery on strictly contractual grounds, e.g. David Ellerman and Carole Pateman, arguing that the employment contract is a legal fiction in that it treats human beings juridically as mere tools or inputs by abdicating responsibility and self-determination, which the critics argue are inalienable. As Ellerman points out, "[t]he employee is legally transformed from being a co-responsible partner to being only an input supplier sharing no legal responsibility for either the input liabilities [costs] or the produced outputs [revenue, profits] of the employer's business".[91] Such contracts are inherently invalid "since the person remain[s] a de facto fully capacitated adult person with only the contractual role of a non-person" as it is impossible to physically transfer self-determination.[92] As Pateman argues:

The contractarian argument is unassailable all the time it is accepted that abilities can 'acquire' an external relation to an individual, and can be treated as if they were property. To treat abilities in this manner is also implicitly to accept that the 'exchange' between employer and worker is like any other exchange of material property ... The answer to the question of how property in the person can be contracted out is that no such procedure is possible. Labour power, capacities or services, cannot be separated from the person of the worker like pieces of property.[93]

In a modern liberal capitalist society, the employment contract is enforced while the enslavement contract is not; the former being considered valid because of its consensual/non-coercive nature and the latter being considered inherently invalid, consensual or not. The noted economist Paul Samuelson described this discrepancy:

Since slavery was abolished, human earning power is forbidden by law to be capitalized. A man is not even free to sell himself; he must rent himself at a wage.[94]

Some advocates of right-libertarianism, among them philosopher Robert Nozick, address this inconsistency in modern societies arguing that a consistently libertarian society would allow and regard as valid consensual/non-coercive enslavement contracts, rejecting the notion of inalienable rights:

The comparable question about an individual is whether a free system will allow him to sell himself into slavery. I believe that it would.[95]

Other economists including Murray Rothbard allow for the possibility of debt slavery, asserting that a lifetime labour contract can be broken so long as the slave pays appropriate damages:

[I]f A has agreed to work for life for B in exchange for 10,000 grams of gold, he will have to return the proportionate amount of property if he terminates the arrangement and ceases to work.[96]

Schools of economics[edit]

In the philosophy of mainstream, neoclassical economics, wage labor is seen as the voluntary sale of one's own time and efforts, just like a carpenter would sell a chair, or a farmer would sell wheat. It is considered neither an antagonistic nor abusive relationship and carries no particular moral implications.[97]

Austrian economics argues that a person is not "free" unless they can sell their labor because otherwise that person has no self-ownership and will be owned by a "third party" of individuals.[98]

Post-Keynesian economics perceives wage slavery as resulting from inequality of bargaining power between labor and capital, which exists when the economy does not "allow labor to organize and form a strong countervailing force".[99]

The two main forms of socialist economics perceive wage slavery differently:

- Libertarian socialism sees it as a lack of workers' self-management in the context of substituting state and capitalist control with political and economic decentralization and confederation.

- State socialists view it as an injustice perpetrated by capitalists and solved through nationalization and social ownership of the means of production.

Criticism[edit]

Some abolitionists in the United States regarded the analogy of wage workers as wage slaves to be spurious.[100] They believed that wage workers were "neither wronged nor oppressed".[101] The abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass declared "Now I am my own master" when he took a paying job.[31] Later in life, he concluded to the contrary "experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other".[102] However, Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans "did not challenge the notion that those who spend their entire lives as wage laborers were comparable to slaves", though they argued that the condition was different, as long as laborers were likely to develop the opportunity to work for themselves in the future, achieving self-employment.[103]

Some advocates of laissez-faire capitalism, among them philosopher Robert Nozick, have said that inalienable rights can be waived if done so voluntarily, saying "the comparable question about an individual is whether a free system will allow him to sell himself into slavery. I believe that it would".[104]

Others such as the anarcho-capitalist economist Walter Block go further and maintain that all rights are in fact alienable, stating voluntary slavery and by extension wage slavery is legitimate.[105]

See also[edit]

- Criticism of capitalism

- Critique of political economy

- Critique of work

- Forced labour

- Labor rights

- Precariat

- Proletariat

- Refusal of work

- Slavery

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "wage slave". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "wage slave". dictionary.com. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Sandel 1996, p. 184.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Conversation with Noam Chomsky". Globetrotter.berkeley.edu. p. 2. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Bolsheviks and Workers Control, 1917–1921: The State and Counter-revolution". Spunk Library. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Avineri 1968, p. 142.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fitzhugh 1857.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c George 1981, "Chapter 15".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ostergaard 1997, p. 133.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cicero, Marcus Tullius (January 1, 1913) [First written in October–November 44 BC]. "Liber I" [Book I]. In Henderson, Jeffrey (ed.). De Officiis [On Duties]. Loeb Classical Library [LCL030] (in Latin and English). Vol. XXI. Translated by Miller, Walter (Digital ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 152–153 (XLII). doi:10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-de_officiis.1913. ISBN 978-0-674-99033-3. OCLC 902696620. OL 7693830M. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018.

XLII. Now in regard to trades and other means of livelihood, which ones are to be considered becoming to a gentleman and which ones are vulgar, we have been taught, in general, as follows. First, those means of livelihood are rejected as undesirable which incur people's ill-will, as those of tax-gatherers and usurers. Unbecoming to a gentleman, too, and vulgar are the means of livelihood of all hired workmen whom we pay for mere manual labour, not for artistic skill; for in their case the very wage they receive is a pledge of their slavery. Vulgar we must consider those also who buy from wholesale merchants to retail immediately; for they would get no profits without a great deal of downright lying; and verily, there is no action that is meaner than misrepresentation. And all mechanics are engaged in vulgar trades; for no workshop can have anything liberal about it. Least respectable of all are those trades which cater for sensual pleasures[.]

- ^ Proudhon 1890.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marx 1969, Chapter VII.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson 1966, p. 599.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson 1966, p. 912.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lazonick 1990, p. 37.

- ^ Foner 1995, p. xix.

- ^ Jensen 2002.

- ^ Lawrence B. Glickman (1999). A Living Wage: American Workers and the Making of Consumer Society. Cornell U.P. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8014-8614-2.

- ^ Goldman 2003, p. 283.

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995. ISBN 0-8028-3784-0. p. 543.

- ^ Marx 1990, p. ?.

- ^ "The Hireling and the Slave – Antislavery Literature Project". Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ Wage Slavery, PBS.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Margo & Steckel 1982.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fogel 1994, p. 391.

- ^ Thoreau 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foner 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weininger 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sandel 1996, pp. 181–84.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Douglass 1994, p. 95

- ^ Douglass 2000, pp. 676

- ^ Douglass 1886, pp. 12–13

- ^ Douglass 1886, pp. 16

- ^ Laurie 1997.

- ^ Engels 1969.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (October–November 1847). "The Principles of Communism". Marxists.org.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 44.

- ^ "The Gray Area: Dislodging Misconceptions about Slavery". Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ "Roman Household Slavery". Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ "The sociology of slavery: Slave occupations". Encyclopædia Britannica. "The highest position slaves ever attained was that of slave minister [...] A few slaves even rose to be monarchs, such as the slaves who became sultans and founded dynasties in Islām. At a level lower than that of slave ministers were other slaves, such as those in the Roman Empire, the Central Asian Samanid domains, Ch'ing China, and elsewhere, who worked in government offices and administered provinces. [...] The stereotype that slaves were careless and could only be trusted to do the crudest forms of manual labor was disproved countless times in societies that had different expectations and proper incentives".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Perlman 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Chomsky 2000.

- ^ Chomsky 2011.

- ^ "Liberty". American Studies. CSI. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ Carsel 1940; Fitzhugh 1857; Norberg 2003.

- ^ Metcalf 2005, p. 201.

- ^ McKay, Iain. B.7.2 Does social mobility make up for class inequality? An Anarchist FAQ: Volume 1

- ^ Graeber 2004, p. 37.

- ^

Beckert, Sven; Rockman, Seth (2016). "Introduction: Slavery's Capitalism". In Beckert, Sven; Rockman, Seth (eds.). Slavery's Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development. Early American Studies. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8122-9309-8. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

Caitlin Rosenthal traces the innovations of modern management to the slave plantation [...]. Rosenthal is among several scholars who have urged the centrality of slavery in the histories of management and accounting.

- ^ Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit 2007, p. 1393.

- ^ Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit 2007, pp. 1401–1402.

- ^ Statistical table of frequency of use

- ^ "Democracy Now". Democracy Now!. October 19, 2007. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1992). "Interview". Archived from the original on July 21, 2006.

- ^ Brendel 1971.

- ^ Graham 2005.

- ^ Aristotle, Politics 1328b–1329a, H. Rackham trans.

- ^ "The Quotations Page: Quote from Aristotle".

- ^ "Social Security History". www.ssa.gov.

- ^ De Grand 2004, pp. 48–51.

- ^ "A People's History of the United States". web.mit.edu.

- ^ Kolko 1962, pp. 725–726: "General Motors' involvement in Germany's military preparations was the logical outcome of its forthright export philosophy of seeking profits wherever and however they might be made, irrespective of political circumstances. [...] By April 1939, G.M. had applied its credo to its fullest limits, for Opel, its wholly owned subsidiary, was (along with Ford) Germany's largest tank producer. [...] The details of additional American business involvement with German industry fill dozens of volumes of government hearings".

- ^ Quote from an interview with Pierre van Paassen (24 July 1936), published in the Toronto Daily Star (5 August 1936)

- ^ Chomsky 1993, p. 19.

- ^ Thye & Lawler 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Price, Friedland & Vinokur 1998.

- ^ Fromm 1995, p. ?.

You can see Fromm discussing these ideas here. - ^ Kuttner 1997, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Ablett 1991, pp. 15–17.

- ^ quoted by Jose Peirats, The CNT in the Spanish Revolution, vol. 2, p. 76

- ^ Gramsci, A. (1992) Prison Notebooks. New York : Columbia University Press, pp. 233–38

- ^ Robinson, Harriet H. "Early Factory Labor in New England," in Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, Fourteenth Annual Report (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1883), pp. 38082, 38788, 39192.

- ^ Schmidt 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Tedrow, Matt (July 4, 2007). "Parecon and Anarcho-Syndicalism: An Interview with Michael Albert". ZNet. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ Ehrenreich 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ehrenreich 2011.

- ^ Klein 2009, p. 232.

- ^ McClelland, Mac. "I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave". Mother Jones (March/April 2012). Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Steuben 1950.

- ^ Chomsky 2002, p. 229.

- ^ "As long as politics is the shadow cast on society by big business, the attenuation of the shadow will not change the substance", in "The Need for a New Party" (1931), Later Works 6, p. 163

- ^ Ferguson 1995.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (July 25, 1976). "The Relevance of Anarcho-syndicalism".

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (September 21, 2007). "A Revolution is Just Below the Surface".

- ^ Hauser 2006.

- ^ "On Just War Theory at West Point Academy: Hauser's theories "could some day provide foundations for a more substantive theory of just war," expanding on some of the existing legal "codifications of these intuitive judgments" that are regularly disregarded by elite power structures. (min 26–30)".

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (July 14, 2004). "Interview".

- ^ "An Anarchist FAQ Section E – What do anarchists think causes ecological problems?". Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Bookchin 1990, p. 44; Bookchin 2001, pp. 1–20; Clark 1983, p. 114; Clark 2004.

- ^ Ellerman 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Ellerman 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Ellerman 2005, p. 32.

- ^ "Ellerman, David, Inalienable Rights and Contracts, 21" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Ellerman 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Rothbard 2009, p. 164 n.34.

- ^ Mankiw 2012.

- ^ Mises 1996, pp. 194–99.

- ^ Bober 2007, pp. 41–42. See also Keen c. 1990.

- ^ Foner, Eric. 1998. The Story of American Freedom. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 66

- ^ McNall, Scott G.; et al. (2002). Current Perspectives in Social Theory. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7623-0762-3.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. Three Addresses on the Relations Subsisting Between the White and Colored People of the United States. p. 13

- ^ p.181-184 Democracy's Discontent By Michael J. Sandel

- ^ Ellerman, David. Translatio versus Concessio. p. 2

- ^ "Toward a Libertarian Theory of Inalienability: A Critique of Rothbard, Barnett, Smith, Kinsella, Gordon, and Epstein".

Bibliography[edit]

- Ablett, Noah (1991) [1912]. The Miners' Next Step. London: Phoenix Books. ISBN 978-0-948984-21-1.

- Avineri, Shlomo (1968). The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09619-5.

- Bober, Stanley (2007). "Marxian economics: its philosophy, message, and contemporary relevance". In Mathew Forstater; Gary Mongiovi; Steven Pressman (eds.). Post Keynesian Macroeconomics: Essays in Honour of Ingrid Rima. Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77231-0.

- Bookchin, Murray (1990). Remaking Society. New York, NY: South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-372-1.

- Bookchin, Murray (2001). Which Way for the Ecology Movement?. Oakland, CA: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-873176-26-9.

- Brendel, Cajo (1971). "Kronstadt: Proletarian Spin-off of the Russian Revolution". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Carsel, Wilfred (1940). "The Slaveholders' Indictment of Northern Wage Slavery". Journal of Southern History. 6 (4): 504–520. doi:10.2307/2192167. JSTOR 2192167.

- Chomsky, Noam (1986). "The Soviet Union Versus Socialism" (PDF). Our Generation. 17 (2): 47–52. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- Chomsky, Noam (1993). Year 501: The Conquest Continues. London: Verso Books. ISBN 978-0-86091-406-8. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Chomsky, Noam (2000). Rogue States: The Rule of Force in World Affairs. New York, NY: South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-612-8.

- Chomsky, Noam (2002). C.P. Otero (ed.). Chomsky on Democracy and Education. London and New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer. ISBN 978-0-415-92631-7.

- Chomsky, Noam (2011) [1999]. Profit over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-888363-82-1.

- Clark, John (1983). The Anarchist Moment: Reflections on Culture, Nature and Power. Montreal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-0-920057-08-7.

- Clark, John (2004) [1992]. "A Social Ecology" (PDF). In Michael E. Zimmerman; et al. (eds.). Environmental Philosophy: From Animal Rights to Radical Ecology (4th ed.). London: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-112695-4.

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2004) [1995]. Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: The 'Fascist' Style of Rule (2nd ed.). London and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33629-1.

- Douglass, Frederick (1886). Three addresses on the relations subsisting between the white and colored people of the United States. Washington [D.C.] : Gibson bros., printers. OCLC 1085619161. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- Douglass, Frederick (1994). Henry Louis Gates (ed.). Douglass: The Autobiographies. New York, NY: Library of America. ISBN 978-0-940450-79-0.

- Douglass, Frederick (2000). Philip S. Foner, Yuval Taylor (ed.). Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-147-4.

- Durham, Meenakshi Gigi; Kellner, Douglas M., eds. (2012) [2001]. Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-65808-6.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara (2009). Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-8749-9.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara (2011) [2001]. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America (10th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Picador. ISBN 978-0-312-62668-6.

- Ellerman, David P. (1992). Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy (PDF). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-309-6. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Ellerman, David P. (2005). "Translatio versus Concessio: Retrieving the Debate about Contracts of Alienation with an Application to Today's Employment Contract" (PDF). Politics & Society. 33 (3): 449–480. doi:10.1177/0032329205278463. S2CID 158624143. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Engels, Friedrich (1969) [1847]. "The Principles of Communism". Marx & Engels: Selected Works, Volume I. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 81–97. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Ferguson, Thomas (1995). Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Political Systems. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-24316-0.

- Fitzhugh, George (1857). Cannibals All! or, Slaves Without Masters. Richmond, VA: A. Morris. ISBN 978-1-4290-1643-8. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Fogel, Robert William (1994) [1992]. Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31219-5.

- Foner, Eric (1995) [1970]. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509497-8.

- Foner, Eric (1998). The Story of American Freedom. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-7567-5804-2.

- Fromm, Erich (1995) [1976]. To Have or to Be?. London and New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1738-1.

- George, Henry (1981) [1883]. Social Problems. New York, NY: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Goldman, Emma (2003). Candace Falk; et al. (eds.). Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, Volume I: Made for America, 1890–1901. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08670-8.

- Graeber, David (2004). Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press. ISBN 978-0-9728196-4-0.

- Graeber, David (2011). Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York, NY: Melville House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-933633-86-2.

- Graham, Robert, ed. (2005). Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE to 1939). Montreal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-1-55164-251-2.

- Hallgrimsdottir, Helga Kristin; Benoit, Cecilia (2007). "From Wage Slaves to Wage Workers: Cultural Opportunity Structures and the Evolution of the Wage Demands of the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor, 1880–1900". Social Forces. 85 (3): 1393–411. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0037. JSTOR 4494978. S2CID 154551793.

- Hauser, Marc (2006). Moral Minds: How Nature Designed Our Universal Sense of Right and Wrong. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-078070-8.

- Hofman Öjermark, May, ed. (2008). "Promoting safe and healthy jobs: The ILO Global Programme on Safety, Health and the Environment (SafeWork)" (PDF). World of Work. 63: 4–11. ISSN 1020-0010. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Jensen, Derrick (2002). The Culture of Make Believe. New York, NY: Context Books. ISBN 978-1-893956-28-5.

- Keen, Steve (c. 1990). The Demise of the Labor Theory of Value. Kensington, New South Wales: University of New South Wales. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Klein, Martin A. (1986). "Review: Slavery in Russia, 1450–1725 by Richard Hellie". American Journal of Sociology. 92 (2): 505–506. doi:10.1086/228533. JSTOR 2780190.

- Klein, Naomi (2009) [1999]. No Logo (10th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Picador. ISBN 978-0-312-42927-0.

- Kolko, Gabriel (1962). "American Business and Germany, 1930–1941". The Western Political Quarterly. 15 (4): 713–728. doi:10.1177/106591296201500411. JSTOR 445548. S2CID 153323832.

- Kuttner, Robert (1997). Everything for Sale: the Virtues and Limits of Markets. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-58392-1.

- Laurie, Bruce (1997) [1989]. Artisans into Workers: Labor in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06660-3.

- Lazonick, William (1990). Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-15416-2.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (2012). Macroeconomics (8th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-4002-4.

- Margo, Robert A.; Steckel, Richard H. (1982). "The Heights of American Slaves: New Evidence on Slave Nutrition and Health". Social Science History. 6 (4): 516–538. doi:10.2307/1170974. JSTOR 1170974. PMID 11633200.

- Marx, Karl (1959) [1844]. "Third Manuscript; Human Requirements and Division of Labour Under the Rule of Private Property". Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Marx, Karl (1969) [1863]. Theories of Surplus Value. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Marx, Karl (1990) [1867]. Capital, Volume I. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044568-8.

- Metcalf, Alida (2005). Family and Frontier in Colonial Brazil. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70652-1.

- Mises, Ludwig von (1996) [1949]. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (4th ed.). San Francisco: Fox & Wilkes. ISBN 978-0-930073-18-3.

- Norberg, Johan (2003). In Defense of Global Capitalism. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute. ISBN 978-1-930865-47-1.

- Ostergaard, Geoffrey (1997). The Tradition of Workers' Control. London: Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0-900384-91-2.

- Perlman, Fredy (2002). The Reproduction of Daily Life. Detroit, MI: Black & Red. ISBN 978-0-934868-17-4.

- Price, Richard H.; Friedland, Daniel S.; Vinokur, Anuram D. (1998). "Job Loss: Hard Times and Eroded Identity" (PDF). In John H. Harvey (ed.). Perspectives on Loss: A Sourcebook. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel. pp. 303–316. ISBN 978-0-87630-909-4.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1890) [1840]. What Is Property? or, An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government. New York, NY: Humboldt Publishing.

- Roediger, David (2007) [1991]. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (revised and expanded ed.). London and New York, NY: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-84467-126-7.

- Rothbard, Murray N. (2009) [1962, 1970]. Man, Economy, and State with Power and Markets (PDF) (2nd ed.). Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute. ISBN 978-1-933550-27-5. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Sandel, Michael J. (1996). Democracy's Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-19744-2.

- Schmidt, Jeff (2000). Disciplined Minds. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9364-1.

- Smith, Mark M. (1998). Debating Slavery: Economy and Society in the Antebellum American South. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57158-6.

- Steuben, John (1950). Strike Strategy. New York, NY: Gaer Associates. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- Takala, J., ed. (2005). Introductory Report: Decent Work – Safe Work (PDF). XVIIth World Congress on Safety and Health at Work. Geneva: International Labour Office. ISBN 978-92-2-117751-7. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Thompson, E. P. (1966) [1963]. The Making of the English Working Class. New York, NY: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-394-70322-0.

- Thoreau, Henry David (2004). Walden (Fully annotated ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10466-0.

- Thye, Shane R.; Lawler, Edward J., eds. (2006). Social Psychology of the Workplace. Advances in Group Processes. Vol. 23. Oxford: JAI Press. ISBN 978-0-7623-1330-3.

- Weininger, Elliot B. (2002). "Class and Causation in Bourdieu". In Jennifer M. Lehmann (ed.). Bringing Capitalism Back For Critique By Social Theory. Current Perspectives in Social Theory. Vol. 21. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 49–114. ISBN 978-0-7623-0762-3.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to wage slavery at Wikiquote

Quotations related to wage slavery at Wikiquote