Farseer trilogy

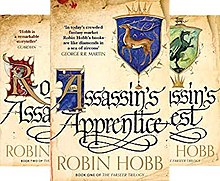

Jackie Morris covers of the 2014 UK edition[1] | |

| Author | Robin Hobb |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | John Howe, Michael Whelan, Stephen Youll |

| Country | United Kingdom, United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Spectra, Voyager |

| Published | 1995–1997 |

| No. of books | 3 |

| Followed by | Liveship Traders |

The Farseer trilogy is a series of fantasy novels by American author Robin Hobb, published from 1995 to 1997. It is often described as epic fantasy, and as a character-driven and introspective work. Set in and around the fictional realm of the Six Duchies, it tells the story of FitzChivalry Farseer (known as Fitz), an illegitimate son of a prince who is trained as an assassin. Political machinations within the royal family threaten his life, and the kingdom is beset by naval raids. Fitz possesses two forms of magic: the telepathic Skill that runs in the royal line, and the socially despised Wit that enables bonding with animals. The series follows his life as he seeks to restore stability to the kingdom.

The story contains motifs from Arthurian legend and is structured as a quest, but focuses on a stereotypically minor character in Fitz: barred by birth from becoming king, he nonetheless embraces a quest without the reward of the throne. It is narrated as a first-person retrospective. Through her portrayal of the Wit, a form of magic Fitz uses to bond with the wolf Nighteyes, Hobb examines otherness and ecological themes. Societal prejudice against the ability causes Fitz to experience persecution and shame, and he leads a closeted life as a Wit user, which scholars see as an allegory for queerness. Hobb also explores queer themes through the Fool, the gender-fluid court jester, and his dynamic with Fitz.

The Farseer trilogy was Margaret Astrid Lindholm Ogden's first work under the pen name Robin Hobb and met with critical and commercial success. Hobb received particular praise for her characterization of Fitz: the Los Angeles Review of Books wrote that the story offered "complete immersion in Fitz's complicated personality",[2] and novelist Steven Erikson described its first-person narrative as a "quiet seduction".[3] The Farseer trilogy is the first of five series set in the Realm of the Elderlings: it is followed by the Liveship Traders trilogy, the Tawny Man trilogy, the Rain Wild chronicles, and the Fitz and the Fool trilogy, which the series concluded with in 2017.

Background

[edit]Writing and publication

[edit]

In the 1980s, American author Margaret Astrid Lindholm Ogden began publishing under the name Megan Lindholm in a variety of genres,[4] including high fantasy,[5] prehistoric fiction,[6] urban fantasy and science fiction.[4] Her work was critically well-received,[7] and her short fiction was nominated for the Hugo and Nebula Awards,[8] but was commercially unsuccessful.[9][10] In 1993, she started writing the Farseer trilogy,[11] an epic fantasy that was in a new style and subgenre compared to her earlier work.[12][13] Feeling that her shifts across genres had prevented her from building a consistent readership,[12] and also that "the drama of adopting a 'secret identity' was irresistible",[13] Lindholm took up a new byline, Robin Hobb, to brand her Farseer work.[12] She continued to write short fiction as Lindholm.[14]

Hobb felt her new pseudonym freed her from reader expectations of a Lindholm book, and she "wrote with a depth of feeling that I didn't usually indulge".[13] The name Robin Hobb was intentionally androgynous and chosen to match the Fitz novels, which were written in a first-person male narrative voice.[9][12] Hobb explained in an interview that she chose the pseudonym because many readers expected a male narrator to have been written by a male author.[12] She continued concealing her identity after publishing the books,[13][15] avoiding public readings or signings of the novels for multiple years, and eventually revealed her pseudonym in an interview with Locus,[13] in 1998.[16]

Hobb has said that the core idea for the Farseer series was: "What if magic were addictive? And what if the addiction was destructive or degenerative?"[16] She said she had mulled over that notion for many years before writing. The first book was initially titled Chivalry's Bastard before becoming Assassin's Apprentice.[11][16] Hobb conceived Fitz's narrative as a trilogy, feeling that his story was too complex to fit in a single book and naturally broke into three parts.[17] A half-wolf called Bruno that moved into her Alaskan home in the 1950s inspired the relationship between Fitz and the wolf Nighteyes.[18] The enigmatic Fool was initially not a big part of the series outline, but grew into a major character as she wrote the novels.[10]

The first volume of the trilogy, Assassin's Apprentice, was published in May 1995 in the US, as a trade paperback by Bantam Spectra.[19][20] Three months later, a hardcover edition was released in the UK by Voyager, a newly launched science fiction and fantasy imprint of HarperCollins.[19][21] The second book, Royal Assassin, followed in 1996, first as a UK hardcover in March by Voyager, and then as a Bantam US paperback in May. The trilogy was completed in 1997 with the release of Assassin's Quest as a hardcover by both publishers, in March in the UK and in April in the US.[4][19] Bantam stylized the US titles in the form of The Farseer I: Assassin's Apprentice;[4][19] Voyager marketed the UK editions as part of the Farseer trilogy, and also as The Farseer Trilogy.[19] The Bantam covers of the first two books were created by Michael Whelan, and the third by Stephen Youll.[19] John Howe illustrated the Voyager editions of all three books.[4][19]

Setting

[edit]The geography of the Six Duchies resembles the US state of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, where Hobb lived for several years.[10][22] Hobb's initial sketches of the setting were inspired by the panhandle of Alaska, and the Six Duchies resembled Kodiak Island,[12] her residence following her marriage,[23] but the final commissioned maps bore a greater similarity to an upside-down Alaska than she had intended.[12] Hobb would write four other series using the same setting, referred to along with the Farseer trilogy as the Realm of the Elderlings.[24]

The society of the fictional universe is comparable to Western feudalism, with nobility owing allegiance to a monarch, and with distinct social stratification, although commoners retain some basic rights.[25] The ruling Farseer line were once raiders, who chose to settle in the kingdom of Six Duchies; the royal family has a tradition of taking allegorical names.[26] The novels' primary society resembles medieval Europe in its technology, following a Tolkienian tradition, but departing from it in depicting far greater gender equality. A few other kingdoms exist that resemble non-Western societies.[25] As the series begins, the Six Duchies is under assault from the "Red-ship Raiders", whose raids bear resemblance to Viking invasions.[27] Two magical powers exist: the Skill, which allows humans to communicate at great distances and for one person to impose their will on another; and the Wit, which allows a bonding without dominance between humans and animals. The former is passed on through the royal bloodline of the Six Duchies; the latter is viewed with revulsion and its practitioners are persecuted.[25]

Plot

[edit]Assassin's Apprentice

[edit]The narrative begins with the protagonist, aged six, being brought from his mother to the royal family of the Six Duchies. He is given the name Fitz, meaning an illegitimate son; he learns that his father is Prince Chivalry Farseer, heir to the throne. The shame of fathering a bastard leads Chivalry to relinquish his position and retreat to the countryside: he dies a few years later, without ever meeting Fitz. Chivalry's brother Prince Verity becomes heir to the throne.

Fitz swears loyalty to King Shrewd and is trained in secret as a royal assassin and diplomat by master Chade. His bloodline grants him access to a form of telepathic magic called the Skill, which he begins to train in under Skillmaster Galen. Galen proceeds to telepathically torture Fitz and blunt his ability to use the Skill; his actions are later revealed to have been at the behest of Fitz's uncle Prince Regal.

Fitz gradually grows aware of his ability to use the Wit, which lets him communicate and bond with animals, but the societal prejudice against this ability leads his guardian Burrich to discourage his early attempts to use it. Fitz's first Wit bond, with a dog named Nosy, ends when the dog is sent away by Burrich. Fitz later adopts another dog, Smithy, and bonds with him in secret, but Smithy is killed defending Burrich.

Regal negotiates a marriage for Verity with Princess Kettricken of the neighboring Mountain Kingdom to strengthen the Six Duchies against the threat of the Red-Ship Raiders. Fitz is sent to the mountains to assassinate Kettricken's brother. He finds Regal plotting to kill Verity and marry Kettricken himself but is able to thwart the attempt.

Royal Assassin

[edit]Returning to Buckkeep, the capital of the Six Duchies, Fitz develops a Wit bond with a wolf named Nighteyes, after buying him as a cub from a trapper. He also develops a romantic relationship with a maid, Molly, and a friendship with the enigmatic court jester, who is known as the Fool. Fitz attempts to keep both his Wit and obligations as an assassin a secret from Molly, but their relationship later ends as the result of conflict over Fitz's duties.

The kingdom continues to be harassed by the Red-Ship raiders of the Out Islands. The raiders are able to turn any captives into "Forged ones"; they are rendered emotionless and behave like feral animals. Prince Verity attempts to wage war on the Red-Ship Raiders through his use of the Skill, and recruits Fitz as an apprentice, creating a Skill link between them. Fitz also hunts the Forged with Nighteyes, relying on their Wit link.

Verity and Fitz are unable to turn the tide of the war, and so Verity departs on a journey in search of Elderlings, beings from myth who may be able to help his people. In Verity's absence, Regal plots to kill his father, King Shrewd, and the pregnant Kettricken. Shrewd dies despite Fitz's efforts, and Fitz is accused of his murder. Regal has him tortured, trying to wrest a confession; on the brink of death, he retreats to Nighteyes' body at the wolf's plea. His seemingly dead body is buried. Burrich and Chade later exhume the body and persuade Fitz to return to it, which he does with regret.

Assassin's Quest

[edit]Fitz spends several months fighting trauma and seizures but is nursed back to health by Burrich. He learns that Regal has taken the throne, and moved the capital inland; taking on a new identity, Fitz travels west, intending to kill Regal. He encounters a community of Witted practitioners known as the Old Blood, whom he learns from but refuses to stay with for long.

Sneaking into Regal's palace, Fitz is captured by Regal's Skilled coterie. He narrowly escapes with the help of Prince Verity, who uses the Skill from afar through their link. Fitz learns that Molly is pregnant with their child and that both Molly and Burrich believe him dead. Wishing to return to them, he is instead compelled to find Verity due to a Skill-summons. Traveling toward the Mountain Kingdom, he is hunted and twice captured by Regal's forces, but escapes. Pursued over the border and severely injured, he is found and tended to by the Fool, and later meets Kettricken, who fled from the Six Duchies after Shrewd's death.

The group follows in Verity's footsteps, seeking to aid him. Journeying out of the Mountain Kingdom on a road wrought with the Skill, they find Verity in a quarry of magical stone, surrounded by inanimate stone dragons. Verity is attempting to carve a dragon himself and awaken it by Skilling his memories, thoughts, and feelings into the stone. With the group's aid, he is successful but loses his humanity to become the stone dragon.

Verity, as a dragon, flies to Buckkeep carrying the rest of the group to combat the raiders. Fitz remains behind with Nighteyes and manages to awaken the other stone dragons, who follow Verity. Fitz battles Regal with the Skill and defeats him, and slays his coterie. Having seen in a Skill vision that Molly and Burrich have fallen in love, he chooses to mask his identity and remain an outcast, living with Nighteyes at the edge of society. Verity destroys the Raiders, and Kettricken assumes the throne.

Style

[edit]The Farseer novels are often described as epic fantasies, and as introspective works that center around the characters' internal conflicts.[2][10] The series is structured as a quest fantasy; the main character is barred from the throne by his birth, but nonetheless embraces a quest without the reward of the throne.[28] In Fitz's case, the quest is to restore the rightful king and bring stability to the kingdom.[29] A review in Asimov's Science Fiction placed his narrative in the tradition of a "young misfit coming of age".[30] While Fitz's quest has a significant impact on the Six Duchies, his roles as assassin and illegitimate royal force his actions to stay unseen and uncredited, and he is thus portrayed both as a leading and marginal character.[31]

The trilogy is described as drawing from Arthurian legend in its characters and narrative motifs: Shrewd's decline recalls the legend of the Fisher King, and Regal bears similarities to Mordred, and Chade to Merlin.[32] Fitz has been termed a melancholy hero,[33] and been discussed as a liminal being, or one who "exists at the threshold of two states".[34] Critics have noted parallels to the character of Hamlet,[35] to Frodo Baggins,[25] and to Severian, the protagonist of Gene Wolfe's The Book of the New Sun.[4] Scholar Geoffrey Elliot describes the setting of the Elderlings books as following in the "Tolkienian tradition", resembling the society of medieval England, but drawing also from the indigenous societies of the Pacific Northwest.[36]

"I remember that first night well, the warmth of the hounds, the prickling straw, and even the sleep that finally came as the pup cuddled close beside me. I drifted into his mind and shared his dim dreams of an endless chase, pursuing a quarry I never saw, but whose hot scent dragged me onward through nettle, bramble, and scree."

Fitz drifting into a dog's dream in Assassin's Apprentice[37]

Hobb uses a style within the fantasy genre that casts the fantastic as an unquestioned, familiar aspect of the setting: this creates an "illusion of familiarity" for the reader, according to scholar Susan Mandala.[38] When Fitz first shares a dream with a dog, the narration matches how he experiences the dream – as a perfectly natural, as opposed to fantastic, event – through language that is "lexically coherent" across the human and animal segments, in Mandala's view.[37][39] Similarly, when Fitz first mentions the telepathic Skill, the narrative does not address the term directly, assuming that its meaning is known in-world, but instead focuses on the Skill's potential effect on Fitz's memory, and its addictive qualities.[40]

The story is narrated as a first-person retrospective, with an adult protagonist reflecting on his childhood memories: this has been described as an unusual style in fantasy,[2][25] and critic John Clute termed it a "painfully confessional memoir".[4] Fitz finds some of his recollections painful and imagines "the hurt of a boy" spilling into the ink; along with this self-commentary, the story is "rich" with implicit clues that "most effectively" uncover Fitz's character, according to Mandala. For instance, Fitz describes his immediate family in the same terms as the strangers he meets: his grandfather becomes "the tall man", and his mother is "a voice" that is distant and unfamiliar, signifying his emotional distance from them.[41] Fitz is on occasion an unreliable narrator who distrusts his own memories.[42][43] The novels contain short memoirs prefacing each chapter that narrate a fictional history of the setting: these excerpts are also unreliable narratives, relaying "recollection and gossip".[44]

Themes

[edit]

Through its fantasy elements, the Farseer trilogy explores themes of otherness.[46] As a practitioner of the Wit, a form of magic described as a connection to all living things, Fitz bonds and shares senses with the wolf Nighteyes.[39] Their relationship is shaped by their contrasting perceptions of the world: the wolf lives "in the now" and unlike Fitz, lingers less on memories and on plans for the distant future.[47] More broadly, the wolf symbolizes nature in Western literature, and the werewolf denotes "slippages between" nature and culture, according to scholar Lenise Prater.[45] The Wit also makes Fitz aware of an interconnectedness between living creatures; by severing such connections, the Raiders turn people into the animalistic Forged. Thereby, Prater argues, Hobb is suggesting that the self is entirely dependent on others, and cannot live autonomously.[48] Scholar Mariah Larsson similarly writes that the depiction of the Wit contains an ecocritical element, highlighting the relevance of non-human life forms and thereby challenging anthropocentrism.[49]

Fitz's internal conflicts in the series – in particular, the sense of shame and trauma that result from his being Witted – have been described by scholars as an allegory for queerness.[50][51] In the world of the Six Duchies, the Wit is seen as an unnatural inclination and its practitioners are persecuted and may be publicly hanged or forced into hiding. Early in the series, Fitz's guardian Burrich punishes him when he tries to use the Wit, viewing it as emasculating and shameful; this is despite Burrich being Witted himself. Burrich rarely speaks of his Wit, having suppressed it for most of his life; he sees the Witted as worse even than the Forged, who have lost their humanity.[52] Scholars regard this as akin to internalized homophobia: Burrich has repudiated a piece of his own identity and seeks to eradicate it in others.[52][53] Fitz thus develops an "identity in shame", according to scholar Peter Melville, and withdraws into the closet, even as he continues to explore the ability.[54]

Fitz's feeling of shame toward the Wit leads him to keep it hidden even from those he cares for, including his beloved Molly. The secret is one of many of Fitz's "multiple closeted lives" that eventually drives Molly away from him.[55] Toward the end of Royal Assassin, Fitz's Witted identity is revealed to the public and he is tortured. After he shifts to the wolf's body and returns, he more openly participates in his Wit-bond and finds a community of the Witted at the edge of society. Comparing the Old Blood to a queer support group, Melville views the sense of connection Fitz experiences in their midst as essential to his self-acceptance.[56] The series then transitions from Fitz's personal struggle to the larger struggle for equal rights for the Witted, which is explored in The Tawny Man trilogy.[56][57] Speaking of her motivation behind the Skill and the Wit, Hobb commented that "I think we can see that in almost any society, something that is accepted and OK in one society makes you a member of a despised group in another society."[58]

Queer themes are also portrayed through the Fool,[59] a character whose subversive aspect is hinted at in Assassin's Quest, when the minstrel Starling states to Fitz: "The Fool is a woman. And she is in love with you." The Fool alternates between masculine and feminine identities through the many Elderlings series; this blurring of gender boundaries is explored further in the Liveship Traders, Tawny Man and Fitz and the Fool trilogies.[60] The dynamic between Fitz and the Fool, described in the Farseer trilogy as "two halves of a whole, sundered and come together again" when they connect via the Skill, is also developed further in later trilogies.[61]

Hobb sharply contrasts the two forms of magic in the series, the Skill and the Wit: though addiction is portrayed as a negative consequence of both,[62] according to Larsson, the Skill is "more insidious".[63] The Skill is practiced by the ruling class, but the Wit is relegated to lower classes; the Skill is also a stereotypically masculine magic, since it functions as a weapon, and the Wit, used to bond with animals, is more feminine.[64] According to Prater, the series deconstructs these stereotypical expectations through Fitz: he possesses both forms of magic and is simultaneously an outcast and a subject of the throne.[64][65] The gendered attributes are blurred in later Elderlings novels, where the Skill is shown to heal and create melodies, while the Wit can be used to manipulate humans.[66] Larsson argues that the narrative "very cleverly" portrays the two abilities such that the reader arrives at a very different impression than the society of the story.[63]

Reception

[edit]Assassin's Apprentice was viewed as the debut work of a new author,[67][68] though a reviewer for Asimov's Science Fiction noted her use of a pseudonym and remarked that the first two books appeared to be the "work of a seasoned professional".[30] Publishers Weekly described the book as a "gleaming debut" in a crowded fantasy market, praising Hobb's portrayal of political machinations within royalty.[67] A similar review from Kirkus termed it "a remarkably assured debut".[68] The sequels Royal Assassin and Assassin's Quest received starred reviews from Publishers Weekly.[69][70] The first book was a finalist for the British Fantasy Award in 1997; the second and third volumes were nominees for the Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel in 1997 and 1998.[71] The series as a whole was commercially successful: worldwide the Elderlings sold more than a million copies by 2003,[72] and UK sales alone had exceeded 1.25 million copies by 2017.[10]

The characters Hobb created received acclaim from several reviewers,[30][73][74][75] and the Farseer novels have been praised as works of character-driven fantasy.[76] Writing in The Times in 2005, critic Amanda Craig praised Hobb's depiction of Fitz and stated that his bond with the wolf Nighteyes was as "passionate as the deepest romantic love".[18] In 2014, the Los Angeles Review of Books reviewer Ilana Teitelbaum described the novels as offering "complete immersion in Fitz's complicated personality", and remarked on the psychological complexity of Fitz's characterization, as well as Hobb's depiction of trauma. Teitelbaum praised the portrayal of Fitz's internal conflicts, noting that his emotional scars shape his perspective and that Fitz isn't ever able to escape them completely.[2] An Interzone review of the first book drew attention to the "wonderfully enigmatic" character of the Fool, whose riddles and predictions were only gifted to others similarly lonely. However, the reviewer criticized Galen, the Skillmaster, as "too manic to be credible".[26]

The novels' prose and fictional setting also drew praise. Scholar Darren Harris-Fain felt that Hobb's "skill" at worldbuilding and characters set the trilogy above most fantasy.[77] David Langford similarly remarked on her construction of a "convincingly textured society" with strong characters, including women,[78] and added that "Hobb writes achingly well".[79] Publishers Weekly described the wolf Nighteyes as her best creation,[70] and Teitelbaum wrote that Hobb's "generosity with detail" allowed the castle of Buckkeep to become a "memorable setting".[2] Publishers Weekly also praised Hobb's "shimmering language",[70] and Fantasy & Science Fiction called her prose in the first volume "skillful",[73] and Library Journal considered it "gracefully written".[80] Interzone noted that Hobb's had avoided the "more obvious clichés", and that the book was "very occasionally brilliant", but found it "stylistically patchy".[26] Fellow novelist Steven Erikson has remarked on Hobb's writing of Fitz's perspective, describing it as a "quiet seduction" and "handled with consummate control, precision and intent". He uses chapters from the trilogy as reading material in his workshops for writers.[3]

The plot of the trilogy, according to Harris-Fain, was an "effectively balance[d]" blend of dark occurrences and warm moments between characters.[77] In a review of Assassin's Apprentice, Booklist felt the plot was traditional but praised its execution.[74] The second book contained plot twists that drew praise from reviewers including Kirkus,[75][81] though the reviewer found "ominous signs" of the narrative losing control.[75] A year later, Kirkus termed the sequel an "enthralling conclusion".[82] The length of the third book was criticized by Booklist and Langford, although both critics praised other facets of Hobb's writing.[83][79] Booklist felt the extra pages delivered in terms of "emotionally compelling scenes of both magic and battle".[83] A review for Locus praised the pacing of the third volume, adding that its "lively dialog" and divergence from a typical quest narrative made it a "great read".[84]

The Farseer novels led to Hobb receiving broader recognition as an exemplar of fantasy writing. The trilogy, as well as its sequels, were viewed by Library Journal as "masterworks of character-based epic fantasy".[76] Comparing the first nine Elderlings novels with the works of Le Guin and Tolkien, The Times described Hobb as "one of the great modern fantasy writers", and stated that her novels were "grown-up fantasy".[18] The Telegraph held that "Hobb is acknowledged – not least by her colleague, George RR Martin – as one of the pre-eminent writers of modern fantasy fiction",[85] and The Guardian described her as "the writer to press on those who turn up their noses at fantasy".[10]

In a discussion of the fantasy canon, medieval scholar Patrick Moran commented that the Elderlings series "undermines the heterosexual norms of traditional high fantasy" through the relationship between Fitz and the genderfluid Fool.[86] While agreeing that Hobb promotes queer themes, Prater voiced disappointment at "conservative impulses" in the series due to a focus on monogamy and romance, which she sees as heteronormative and limiting its message.[87] A more positive view was expressed by Melville, who contended that the concluding Fitz and the Fool trilogy "confirms the series' place within the larger history of queerness in the fantasy genre".[88]

Sequels and adaptations

[edit]The Farseer trilogy is followed by four series set in the Realm of the Elderlings, the last volume of which was published in 2017.[4][10] The second trilogy is the Liveship Traders, which is written in the third person and set in a different part of the Elderlings world, but with a recurring character.[89] Hobb then returns to Fitz's first-person narration in the Tawny Man trilogy.[90] Next in chronology are the four novels of the Rain Wild chronicles and the Fitz and the Fool trilogy, which concludes the series.[91][92]

The series was adapted as a comic book in French under the title L'Assassin Royal. Spanning ten volumes, it was published from 2008 to 2016 by Soleil Productions.[93][94] An English-language comic adaptation of Assassin's Apprentice is slated for release in December 2022. Co-written by Hobb and Jody Houser, the series is planned to comprise six issues and features artist Ryan Kelly, colorist Jordie Bellaire, letterer Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou and publisher Dark Horse Comics.[95] In a 2018 interview, Hobb stated she had not sold television or film rights to the series.[96]

References

[edit]- ^ "A New Look for The Farseer Trilogy". HarperVoyager. February 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Teitelbaum, Ilana (September 8, 2014). "Bright Home, Dark Heart". Los Angeles Review of Books.

- ^ a b Erikson, Steven (April 27, 2016). "How Robin Hobb's Assassin's Apprentice Pulls the Rug Out from Under You". Tor.com. Macmillan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clute, John (October 29, 2021). "Hobb, Robin". In Clute, John; et al. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (3rd ed.). Gollancz.

- ^ Harris-Fain (1999), p. 388.

- ^ Holliday & Morgan (1996), pp. 364–365.

- ^ Blaschke (2005), p. 55.

- ^ "Megan Lindholm Awards". Science Fiction Awards Database. Locus Science Fiction Foundation. November 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Blaschke (2005), p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g Flood, Alison (July 28, 2017). "Robin Hobb: 'Fantasy Has Become Something You Don't Have to Be Embarrassed About'". The Guardian.

- ^ a b

Pomerico, David (June 21, 2010). "25 Years of Spectra: Assassin's Apprentice by Robin Hobb". Suvudu. Random House. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Adams, John Joseph; Kirtley, David Barr (April 2012). "Interview: Robin Hobb". Lightspeed. Vol. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Anders, Charlie Jane (April 14, 2011). "Find Out How Robin Hobb Became Two Different People". io9.

- ^ Blaschke (2005), p. 59.

- ^ Blaschke (2005), pp. 55, 58.

- ^ a b c "Robin Hobb: Behind the Scenes". Locus. Vol. 40, no. 1. January 1998.

- ^ Blaschke (2005), p. 57.

- ^ a b c Craig, Amanda (September 17, 2005). "Hits and Near Myths". The Times. Gale IF0502926968.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown & Contento (1999).

- ^ Holliday & Morgan (1996), p. 364.

- ^ Johnson, Jane (August 13, 2015). "How Megan Lindholm Became Robin Hobb". Sainsbury's eBooks Blog. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016.

- ^ Elliott (2015), p. 188.

- ^ Cardy, Tom (June 24, 2014). "The Mother of Dragons". The Dominion Post – via Stuff.

- ^ Larsson (2021), pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c d e Elliott (2006).

- ^ a b c Morgan, Chris (August 1995). "First Fantasies". Interzone. No. 98.

- ^ Senior (2012), p. 197.

- ^ Mendlesohn (2014), p. 56.

- ^ Senior (2012), pp. 197–199.

- ^ a b c Heck, Peter (February 1997). "Assassin's Apprentice and Royal Assassin". Asimov's Science Fiction. Vol. 21, no. 2.

- ^ Oliver (2022), p. 46.

- ^ Senior (2012), pp. 197–198.

- ^ Flood, Alison (September 10, 2014). "Fool's Assassin by Robin Hobb – A Melancholic Hero Fights Again". The Guardian.

- ^ Kaveney, Roz (1997). "Liminal Beings". In Clute, John; Grant, John (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. St. Martin's Griffin.

- ^ Craig, Amanda (August 14, 2015). "Fool's Quest, by Robin Hobb – Book Review: More Swords and Sorcery from a Dame of Thrones". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022.

- ^ Elliott (2015), pp. 185–189.

- ^ a b Mandala (2010), p. 102.

- ^ Mandala (2010), pp. 100–102.

- ^ a b Larsson (2021), pp. 130–131.

- ^ Mandala (2010), pp. 101–102.

- ^ Mandala (2010), pp. 128–130.

- ^ Melville (2018), p. 282.

- ^ Mendlesohn (2014), p. 11.

- ^ Mendlesohn (2014), p. 16.

- ^ a b Prater (2016), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Prater (2016), p. 23.

- ^ Larsson (2021), p. 134.

- ^ Prater (2016), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Larsson (2021), p. 124.

- ^ Melville (2018), p. 284.

- ^ Larsson (2021), pp. 126, 130.

- ^ a b Melville (2018), pp. 285–287.

- ^ Larsson (2021), p. 130.

- ^ Melville (2018), p. 288.

- ^ Melville (2018), pp. 288–289.

- ^ a b Melville (2018), p. 289.

- ^ Larsson (2021), p. 132.

- ^ Zutter, Natalie (October 24, 2019). "'I Have Been Incredibly Privileged to Write the Full Arc of Fitz's Story': Robin Hobb on 25 Years of Assassin's Apprentice". Tor.com. Macmillan.

- ^ Larsson (2021), pp. 126–127.

- ^ Prater (2016), p. 29.

- ^ Melville (2018), p. 294.

- ^ Case (2005), pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Larsson (2021), pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b Prater (2016), pp. 23–25.

- ^ Melville (2018), pp. 284–285.

- ^ Prater (2016), p. 25.

- ^ a b "Assassin's Apprentice". Publishers Weekly. April 3, 1995.

- ^ a b "Assassin's Apprentice". Kirkus Reviews. March 1, 1995.

- ^ "Royal Assassin". Publishers Weekly. April 1, 1996.

- ^ a b c "Assassin's Quest". Publishers Weekly. March 3, 1997.

- ^ "Robin Hobb Titles". Science Fiction Awards Database. Locus Science Fiction Foundation. August 31, 2020.

- ^ O'Neill, John (April 23, 2017). "Robin Hobb Wraps Up the Fitz and the Fool Trilogy with Assassin's Fate". Black Gate.

- ^ a b "The Farseer: Assassin's Apprentice by Robin Hobb". The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Vol. 91, no. 6. December 1996. p. 98. EBSCOhost 9611124567.

- ^ a b Green, Roland (April 1, 1995). "Assassin's Apprentice". Booklist. Vol. 91, no. 15. Gale A16849560.

- ^ a b c "Royal Assassin". Kirkus Reviews. March 1, 1996.

- ^ a b Hollands, Neil (April 1, 2010). "Fiction's Fools: Wise and Witty Reads". Library Journal. Vol. 135, no. 6. Gale A223749292. ProQuest 196819155.

- ^ a b Harris-Fain (1999), p. 380.

- ^ Langford, David (September 1995). "Robin Hobb: The Assassin's Apprentice". SFX. No. 4 – via Ansible.

- ^ a b Langford, David (April 1997). "Robin Hobb: Assassin's Quest". SFX. No. 24 – via Ansible.

- ^ Cassada, Jackie (March 15, 1995). "Hobb, Robin. The Farseer: Assassin's Apprentice". Library Journal. Vol. 120, no. 5. pp. 100–101. EBSCOhost 9503177634.

- ^ "The Farseer: Royal Assassin by Robin Hobb". The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Vol. 91, no. 6. December 1996. p. 98. EBSCOhost 9611124569.

- ^ "Assassin's Quest". Kirkus Reviews. February 1, 1997.

- ^ a b Green, Roland (February 1, 1997). "Assassin's Quest". Booklist. Vol. 93, no. 11. Gale A19122084.

- ^ Cushman, Carolyn (March 1997). "Robin Hobb, Assassin's Quest". Locus. Vol. 38, no. 3.

- ^ Shilling, Jane (August 23, 2014). "Fool's Assassin by Robin Hobb, Review: 'High Art'". The Daily Telegraph. ProQuest 1555423441.

- ^ Moran (2019), p. 64.

- ^ Prater (2016), pp. 21, 30–32.

- ^ Melville (2018), p. 300.

- ^ Prater (2016), pp. 29, 33.

- ^ Prater (2016), p. 33.

- ^ Larsson (2021), p. 125.

- ^ Templeton, Molly (June 7, 2019). "Assassins, Pirates, or Dragons: Where to Start with the Work of Robin Hobb". Tor.com. Macmillan.

- ^ "Assassin Royal 01 – Le Bâtard". Soleil Productions (in French). September 24, 2008. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. ISBN 978-2-302-00299-9. OCLC 904568192.

- ^ "Assassin Royal 10 – Vérité le Dragon". Soleil Productions (in French). September 7, 2016. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. ISBN 978-2-302-05363-2. OCLC 964524643.

- ^ Alverson, Brigid (September 12, 2022). "Dark Horse to Adapt 'Farseer' Trilogy into Comics". ICv2.

- ^ Larsson (2021), p. 126.

Sources

[edit]Primary

- Hobb, Robin (May 1995). Assassin's Apprentice (trade paperback). Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-37445-1.

- Hobb, Robin (August 1995). Assassin's Apprentice (hardcover). HarperCollins Voyager. ISBN 0-00-224606-6.

- Hobb, Robin (March 1996). Royal Assassin (hardcover). HarperCollins Voyager. ISBN 0-00-224607-4.

- Hobb, Robin (May 1996). Royal Assassin (paperback). Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-37563-6.

- Hobb, Robin (March 1997). Assassin's Quest (hardcover). HarperCollins Voyager. ISBN 0-00-224608-2.

- Hobb, Robin (April 1997). Assassin's Quest (hardcover). Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-10640-6.

Secondary

- Blaschke, Jayme Lynn (2005). Voices of Vision: Creators of Science Fiction and Fantasy Speak. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6239-3.

- Brown, Charles N.; Contento, William G. (1999). "Hobb, Robin". The Locus Index to Science Fiction: 1984–1998. Locus. OCLC 47672336.

- Case, Caroline (2005). Imagining Animals: Art, Psychotherapy and Primitive States of Mind. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315820156. ISBN 978-1-317-82202-8.

- Elliott, Geoffrey B. (2006). "Shades of Steel-Gray: The Nuanced Warrior-Hero in the Farseer Trilogy". Studies in Fantasy Literature. 4: 70–78. OCLC 133466088.

- Elliott, Geoffrey B. (2015). "Moving beyond Tolkien's Medievalism: Robin Hobb's Farseer and Tawny Man Trilogies". In Young, Helen (ed.). Fantasy and Science Fiction Medievalisms: From Isaac Asimov to A Game of Thrones. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-62499-883-6.

- Harris-Fain, Darren (1999). "Contemporary Fantasy, 1957–1998". In Barron, Neil (ed.). Fantasy and Horror. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3596-2.

- Holliday, Liz; Morgan, Chris (1996). "Lindholm, Megan". In Pringle, David (ed.). St. James Guide to Fantasy Writers. St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-205-0.

- Larsson, Mariah (2021). "Bringing Dragons Back into the World: Dismantling the Anthropocene in Robin Hobb's The Realm of the Elderlings". In Höglund, Anna; Trenter, Cecilia (eds.). The Enduring Fantastic: Essays on Imagination and Western Culture. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-8012-5.

- Mandala, Susan (2010). Language in Science Fiction and Fantasy: The Question of Style. Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-4106-4.

- Melville, Peter (2018). "Queerness and Homophobia in Robin Hobb's Farseer Trilogies". Extrapolation. 59 (3): 281–303. doi:10.3828/extr.2018.17. ProQuest 2156322163.

- Mendlesohn, Farah (2014). Rhetorics of Fantasy. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-7391-9. Project MUSE book 21231.

- Moran, Patrick (2019). The Canons of Fantasy: Lands of High Adventure. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108769815. ISBN 978-1-108-76981-5. S2CID 213876317.

- Oliver, Matthew (2022). "History in the Margins: Epigraphs and Negative Space in Robin Hobb's Assassin's Apprentice". Mythlore. 41 (1): 45–66. JSTOR 48692593.

- Prater, Lenise (2016). "Queering Magic: Robin Hobb and Fantasy Literature's Radical Potential". In Roberts, Jude; MacCallum-Stewart, Esther (eds.). Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Popular Fantasy: Beyond Boy Wizards and Kick-Ass Chicks. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315583938-3. ISBN 978-1-317-13054-3.

- Senior, W. A. (2012). "Quest Fantasies". In James, Edward; Mendlesohn, Farah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 190–199. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521429597.018. ISBN 978-0-521-42959-7.

External links

[edit]- Farseer trilogy series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database