Allies of World War II

Allies of World War II | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939–1945 | |||||||

The Big Three:

Allied combatants with governments-in-exile:

Other Allied combatant states:

Co-belligerents (former Axis powers):

| |||||||

| Status | Military alliance | ||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||

| February 1921 | |||||||

| August 1939 | |||||||

| September 1939 – June 1940 | |||||||

| June 1941 | |||||||

| July 1941 | |||||||

| August 1941 | |||||||

| January 1942 | |||||||

| May 1942 | |||||||

| November–December 1943 | |||||||

| 1–15 July 1944 | |||||||

| 4–11 February 1945 | |||||||

| April–June 1945 | |||||||

| July–August 1945 | |||||||

| |||||||

Footnotes | |||||||

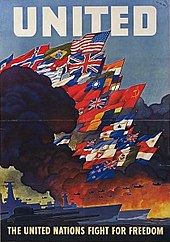

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during World War II (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers. Its principal members by the end of 1941 were the "Big Four" – the United Kingdom, United States, Soviet Union, and China.

Membership in the Allies varied during the course of the war. When the conflict broke out on 1 September 1939, the Allied coalition consisted of the United Kingdom, France, and Poland, as well as their respective dependencies, such as British India. They were soon joined by the independent dominions of the British Commonwealth: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Consequently, the initial alliance resembled that of the First World War. As Axis forces began invading northern Europe and the Balkans, the Allies added the Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Greece, and Yugoslavia. The Soviet Union, which initially had a nonaggression pact with Germany and participated in its invasion of Poland, joined the Allies after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.[1][failed verification] The United States, while providing some materiel support to European Allies since September 1940, remained formally neutral until the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, after which it declared war and officially joined the Allies. China had already been at war with Japan since 1937, and formally joined the Allies in December 1941.

The Allies were led by the so-called "Big Three"—the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and the United States—which were the principal contributors of manpower, resources, and strategy, each playing a key role in achieving victory.[2][3][4] A series of conferences between Allied leaders, diplomats, and military officials gradually shaped the makeup of the alliance, the direction of the war, and ultimately the postwar international order. Relations between the United Kingdom and the United States were especially close, with their bilateral Atlantic Charter forming the groundwork of their alliance.

The Allies became a formalized group upon the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942, which was signed by 26 nations around the world; these ranged from governments in exile from the Axis occupation to small nations far removed from the war. The Declaration officially recognized the Big Three and China as the "Four Powers",[5] acknowledging their central role in prosecuting the war; they were also referred to as the "trusteeship of the powerful", and later as the "Four Policemen" of the United Nations.[6] Many more countries joined through to the final days of the war, including colonies and former Axis nations. After the war ended, the Allies, and the Declaration that bound them, would become the basis of the modern United Nations;[7] one enduring legacy of the alliance is the permanent membership of the U.N. Security Council, which is made up exclusively of the principal Allied powers that won the war.

Origins

The victorious Allies of World War I—which included what would become the Allied powers of the Second World War—had imposed harsh terms on the opposing Central Powers in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920. Germany resented signing the Treaty of Versailles, which required that it take full responsibility for the war, lose a significant portion of territory, and pay costly reparations, among other penalties. The Weimar Republic, which formed at the end of the war and subsequently negotiated the treaty, saw its legitimacy shaken, particularly as it struggled to govern a greatly weakened economy and humiliated populace.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, and the ensuing Great Depression, led to political unrest across Europe, especially in Germany, where revanchist nationalists blamed the severity of the economic crisis on the Treaty of Versailles. The far-right Nazi Party led by Adolf Hitler, which had formed shortly after the peace treaty, exploited growing popular resentment and desperation to become the dominant political movement in Germany. By 1933, they gained power and rapidly established a totalitarian regime known as Nazi Germany. The Nazi regime demanded the immediate cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles and made claims over German-populated Austria and the German-populated territories of Czechoslovakia. The likelihood of war was high, but none of the major powers had the appetite for another conflict; many governments sought to ease tensions through nonmilitary strategies such as appeasement.

Japan, which was a principal allied power in the First World War, had since become increasingly militaristic and imperialistic; parallel to Germany, nationalist sentiment increased throughout the 1920s, culminating in the invasion of Manchuria in 1931. The League of Nations strongly condemned the attack as an act of aggression against China; Japan responded by leaving the League in 1933. The second Sino-Japanese War erupted in 1937 with Japan's full-scale invasion of China. The League of Nations condemned Japan's actions and initiated sanctions; the United States, which had attempted to peacefully negotiate for peace in Asia, was especially angered by the invasion and sought to support China.

In March 1939, Germany took over Czechoslovakia, just six months after signing the Munich Agreement, which sought to appease Hitler by ceding the mainly ethnic German Czechoslovak borderlands; while most of Europe had celebrated the agreement as a major victory for peace, the open flaunting of its terms demonstrated the failure of appeasement. Britain and France, which had been the main advocates of appeasement, decided that Hitler had no intention to uphold diplomatic agreements and responded by preparing for war. On 31 March 1939, Britain formed the Anglo-Polish military alliance in an effort to avert an imminent German attack on Poland; the French likewise had a long-standing alliance with Poland since 1921.

The Soviet Union, which had been diplomatically and economically isolated by much of the world, had sought an alliance with the western powers, but Hitler preempted a potential war with Stalin by signing the Nazi–Soviet non-aggression pact in August 1939. In addition to preventing a two-front war that had battered its forces in the last world war, the agreement secretly divided the independent states of Central and Eastern Europe between the two powers and assured adequate oil supplies for the German war machine.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland; two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany. Roughly two weeks after Germany's attack, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. Britain and France established the Anglo-French Supreme War Council to coordinate military decisions. A Polish government-in-exile was set up in London, joined by hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers, which would remain an Allied nation until the end. After a quiet winter, Germany began its invasion of Western Europe in April 1940, quickly defeating Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. All the occupied nations subsequently established a government-in-exile in London, with each contributing a contingent of escaped troops. Nevertheless, by roughly one year since Germany's violation of the Munich Agreement, Britain and its Empire stood alone against Hitler and Mussolini.

Formation of the "Grand Alliance"

Before they were formally allied, the United Kingdom and the United States had cooperated in a number of ways,[2] notably through the destroyers-for-bases deal in September 1940 and the American Lend-Lease program, which provided Britain and the Soviet Union with war materiel beginning in October 1941.[8][9] The British Commonwealth and, to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union reciprocated with a smaller Reverse Lend-Lease program.[10][11]

The First Inter-Allied Meeting took place in London in early June 1941 between the United Kingdom, the four co-belligerent British Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa), the eight governments in exile (Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia) and Free France. The meeting culminated with the Declaration of St James's Palace, which set out a first vision for the postwar world.

In June 1941, Hitler broke the non-aggression agreement with Stalin and Axis forces invaded the Soviet Union, which consequently declared war on Germany and its allies. Britain agreed to an alliance with the Soviet Union in July, with both nations committing to assisting one another by any means, and to never negotiate a separate peace.[12] The following August saw the Atlantic Conference between American President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, which defined a common Anglo-American vision of the postwar world, as formalized by the Atlantic Charter.[13]

At the Second Inter-Allied Meeting in London in September 1941, the eight European governments in exile, together with the Soviet Union and representatives of the Free French Forces, unanimously adopted adherence to the common principles of policy set forth in the Atlantic Charter. In December, Japan attacked American and British territories in Asia and the Pacific, resulting in the U.S. formally entering the war as an Allied power. Still reeling from Japanese aggression, China declared war on all the Axis powers shortly thereafter.

By the end of 1941, the main lines of World War II had formed. Churchill referred to the "Grand Alliance" of the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union,[14][15] which together played the largest role in prosecuting the war. The alliance was largely one of convenience for each member: the U.K. realized that the Axis powers threatened not only its colonies in North Africa and Asia but also the homeland. The United States felt that the Japanese and German expansion should be contained, but ruled out force until Japan's attack. The Soviet Union, having been betrayed by the Axis attack in 1941, greatly despised German belligerence and the unchallenged Japanese expansion in the East, particularly considering their defeat in previous wars with Japan; the Soviets also recognized, as the U.S. and Britain had suggested, the advantages of a two-front war.

The Big Three

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin were The Big Three leaders. They were in frequent contact through ambassadors, top generals, foreign ministers and special emissaries such as the American Harry Hopkins. It is also often called the "Strange Alliance", because it united the leaders of the world's greatest capitalist state (the United States), the greatest socialist state (the Soviet Union) and the greatest colonial power (the United Kingdom).[16]

Relations between them resulted in the major decisions that shaped the war effort and planned for the postwar world.[4][17] Cooperation between the United Kingdom and the United States was especially close and included forming a Combined Chiefs of Staff.[18]

There were numerous high-level conferences; in total Churchill attended 14 meetings, Roosevelt 12, and Stalin 5. Most visible were the three summit conferences that brought together the three top leaders.[19][20] The Allied policy toward Germany and Japan evolved and developed at these three conferences.[21]

- Tehran Conference (codename "Eureka") – first meeting of The Big Three (28 November 1943 – 1 December 1943)

- Yalta Conference (codename "Argonaut") – second meeting of The Big Three (4–11 February 1945)

- Potsdam Conference (codename "Terminal") – third and final meeting of The Big Three (Truman having taken over for Roosevelt, 17 July – 2 August 1945)

Tensions

There were many tensions among the Big Three leaders, although they were not enough to break the alliance during wartime.[3][22]

In 1942 Roosevelt proposed becoming, with China, the Four Policemen of world peace. Although the 'Four Powers' were reflected in the wording of the Declaration by United Nations, Roosevelt's proposal was not initially supported by Churchill or Stalin.

Division emerged over the length of time taken by the Western Allies to establish a second front in Europe.[23] Stalin and the Soviets used the potential employment of the second front as an 'acid test' for their relations with the Anglo-American powers.[24] The Soviets were forced to use as much manpower as possible in the fight against the Germans, whereas the United States had the luxury of flexing industrial power, but with the "minimum possible expenditure of American lives".[24] Roosevelt and Churchill opened ground fronts in North Africa in 1942 and in Italy in 1943, and launched a massive air attack on Germany, but Stalin kept wanting more.

Although the U.S. had a strained relationship with the USSR in the 1920s, relations were normalized in 1933. The original terms of the Lend-Lease loan were amended towards the Soviets, to be put in line with British terms. The United States would now expect interest with the repayment from the Soviets, following the initiation of the Operation Barbarossa, at the end of the war—the United States were not looking to support any "postwar Soviet reconstruction efforts",[25] which eventually manifested into the Molotov Plan. At the Tehran conference, Stalin judged Roosevelt to be a "lightweight compared to the more formidable Churchill".[26][27] During the meetings from 1943 to 1945, there were disputes over the growing list of demands from the USSR.

Tensions increased further when Roosevelt died and his successor Harry Truman rejected demands put forth by Stalin.[23] Roosevelt wanted to play down these ideological tensions.[28] Roosevelt felt he "understood Stalin's psychology", stating "Stalin was too anxious to prove a point ... he suffered from an inferiority complex."[29]

United Nations

Four Policemen

During December 1941, Roosevelt devised the name "United Nations" for the Allies and Churchill agreed.[30][31] He referred to the Big Three and China as the "Four Policemen" repeatedly from 1942.[32]

Declaration by United Nations

The alliance was formalised in the Declaration by United Nations signed on 1 January 1942. There were the 26 original signatories of the declaration; the Big Four were listed first:

Alliance growing

The United Nations began growing immediately after its formation. In 1942, Mexico, the Philippines and Ethiopia adhered to the declaration. Ethiopia had been restored to independence by British forces after the Italian defeat in 1941. The Philippines, still owned by Washington but granted international diplomatic recognition, was allowed to join on 10 June despite its occupation by Japan.

In 1943, the Declaration was signed by Iraq, Iran, Brazil, Bolivia and Colombia. A Tripartite Treaty of Alliance with Britain and the USSR formalised Iran's assistance to the Allies.[33] In Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian dictator Getúlio Vargas was considered near to fascist ideas, but realistically joined the United Nations after their evident successes.[citation needed]

In 1944, Liberia and France signed. The French situation was very confused. Free French forces were recognized only by Britain, while the United States considered Vichy France to be the legal government of the country until Operation Overlord, while also preparing U.S. occupation francs. Winston Churchill urged Roosevelt to restore France to its status of a major power after the liberation of Paris in August 1944; the Prime Minister feared that after the war, Britain could remain the sole great power in Europe facing the Communist threat, as it was in 1940 and 1941 against Nazism.

During the early part of 1945, Peru, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, Uruguay, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Syria (these latter two French colonies had been declared independent states by British occupation troops, despite protests by Pétain and later De Gaulle) and Ecuador became signatories. Ukraine and Belarus, which were not independent states but parts of the Soviet Union, were accepted as members of the United Nations as a way to provide greater influence to Stalin, who had only Yugoslavia as a communist partner in the alliance.

Major affiliated state combatants

United Kingdom

British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain delivered his Ultimatum Speech on 3 September 1939 which declared war on Germany, a few hours before France. As the Statute of Westminster 1931 was not yet ratified by the parliaments of Australia and New Zealand, the British declaration of war on Germany also applied to those dominions. The other dominions and members of the British Commonwealth declared war from 3 September 1939, all within one week of each other; they were Canada, British India and South Africa.[34]

During the war, Churchill attended seventeen Allied conferences at which key decisions and agreements were made. He was "the most important of the Allied leaders during the first half of World War II".[35]

African colonies and dependencies

British West Africa and the British colonies in East and Southern Africa participated, mainly in the North African, East African and Middle-Eastern theatres. Two West African and one East African division served in the Burma Campaign.

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing colony, having received responsible government in 1923. It was not a sovereign dominion. It governed itself internally and controlled its own armed forces, but had no diplomatic autonomy, and, therefore, was officially at war as soon as Britain was at war. The Southern Rhodesian colonial government issued a symbolic declaration of war nevertheless on 3 September 1939, which made no difference diplomatically but preceded the declarations of war made by all other British dominions and colonies.[36]

American colonies and dependencies

These included: the British West Indies, British Honduras, British Guiana and the Falkland Islands. The Dominion of Newfoundland was directly ruled as a royal colony from 1933 to 1949, run by a governor appointed by London who made the decisions regarding Newfoundland.

Asia

British India included the areas and peoples covered by later India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and (until 1937) Burma/Myanmar, which later became a separate colony.

British Malaya covers the areas of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore, while British Borneo covers the area of Brunei, including Sabah and Sarawak of Malaysia.

British Hong Kong consisted of Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, and the New Territories.

Territories controlled by the Colonial Office, namely the Crown Colonies, were controlled politically by the UK and therefore also entered hostilities with Britain's declaration of war. At the outbreak of World War II, the British Indian Army numbered 205,000 men. Later during World War II, the British Indian Army became the largest all-volunteer force in history, rising to over 2.5 million men in size.

Indian soldiers earned 30 Victoria Crosses during the Second World War. It suffered 87,000 military casualties (more than any Crown colony but fewer than the United Kingdom). The UK suffered 382,000 military casualties.

Kuwait was a protectorate of the United Kingdom formally established in 1899. The Trucial States were British protectorates in the Persian Gulf.

Palestine was a mandate dependency created in the peace agreements after World War I from the former territory of the Ottoman Empire, Iraq.

Europe

The Cyprus Regiment was formed by the British Government during the Second World War and made part of the British Army structure. It was mostly Greek Cypriot volunteers and Turkish Cypriot inhabitants of Cyprus but also included other Commonwealth nationalities. On a brief visit to Cyprus in 1943, Winston Churchill praised the "soldiers of the Cyprus Regiment who have served honourably on many fields from Libya to Dunkirk". About 30,000 Cypriots served in the Cyprus Regiment. The regiment was involved in action from the very start and served at Dunkirk, in the Greek Campaign (about 600 soldiers were captured in Kalamata in 1941), North Africa (Operation Compass), France, the Middle East and Italy. Many soldiers were taken prisoner especially at the beginning of the war and were interned in various PoW camps (Stalag) including Lamsdorf (Stalag VIII-B), Stalag IVC at Wistritz bei Teplitz and Stalag 4b near Most in the Czech Republic. The soldiers captured in Kalamata were transported by train to prisoner of war camps.

France

War declared

After Germany invaded Poland, France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939.[37] In January 1940, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier made a major speech denouncing the actions of Germany:

At the end of five months of war, one thing has become more and more clear. It is that Germany seeks to establish a domination of the world completely different from any known in world history.

The domination at which the Nazis aim is not limited to the displacement of the balance of power and the imposition of the supremacy of one nation. It seeks the systematic and total destruction of those conquered by Hitler and it does not treaty with the nations which it has subdued. He destroys them. He takes from them their whole political and economic existence and seeks even to deprive them of their history and culture. He wishes only to consider them as vital space and a vacant territory over which he has every right.

The human beings who constitute these nations are for him only cattle. He orders their massacre or migration. He compels them to make room for their conquerors. He does not even take the trouble to impose any war tribute on them. He just takes all their wealth and, to prevent any revolt, he scientifically seeks the physical and moral degradation of those whose independence he has taken away.[37]

France experienced several major phases of action during World War II:

- The "Phoney War" of 1939–1940, also called drôle de guerre in France, dziwna wojna in Poland (both meaning "Strange War"), or the Sitzkrieg ("Sitting War", a pun on Blitzkrieg) in Germany.

- The Battle of France in May–June 1940, which resulted in the defeat of the Allies, the fall of the French Third Republic, the German occupation of northern and western France, and the creation of the rump state Vichy France, which received diplomatic recognition from the Axis and most neutral countries including the United States.[38]

- The period of resistance against the occupation and Franco-French struggle for control of the colonies between the Vichy regime and the Free French, who continued the fight on the Allies' side after the Appeal of 18 June by General Charles de Gaulle, recognized by the United Kingdom as France's government-in-exile. It culminated in the Allied landings in North Africa on 11 November 1942, when Vichy ceased to exist as an independent entity after having been invaded by both the Axis and the Allies simultaneously, being thereafter only the nominal government in charge during the occupation of France. Vichy forces in French North Africa switched allegiance and merged with the Free French to participate in the campaigns of Tunisia and of Italy and the invasion of Corsica in 1943–44.

- The liberation of mainland France beginning with D-Day on 6 June 1944 and operation Overlord, and then with operation Dragoon on 15 August 1944, leading to the Liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944 by the Free French 2e Division Blindée and the installation of the Provisional Government of the French Republic in the newly liberated capital.

- Participation of the re-established provisional French Republic's First Army in the Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine and the Western Allied invasion of Germany until V-E Day on 8 May 1945.

Colonies and dependencies

Africa

In Africa these included: French West Africa, French Equatorial Africa, the League of Nations mandates of French Cameroun and French Togoland, French Madagascar, French Somaliland, and the protectorates of French Tunisia and French Morocco.

French Algeria was then not a colony or dependency but a fully-fledged part of metropolitan France.

Asia and Oceania

In Asia and Oceania France has several territories: French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, New Caledonia, the New Hebrides, French Indochina, French India, Guangzhouwan, the mandates of Greater Lebanon and French Syria. The French government in 1936 attempted to grant independence to its mandate of Syria in the Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence of 1936 signed by France and Syria. However, opposition to the treaty grew in France and the treaty was not ratified. Syria had become an official republic in 1930 and was largely self-governing. In 1941, a British-led invasion supported by Free French forces expelled Vichy French forces in Operation Exporter.

Americas

France had several colonies in America, namely Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana and Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

Soviet Union

History

In the lead-up to the war between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, relations between the two states underwent several stages. General Secretary Joseph Stalin and the government of the Soviet Union had supported so-called popular front movements of anti-fascists including communists and non-communists from 1935 to 1939.[39] The popular front strategy was terminated from 1939 to 1941, when the Soviet Union cooperated with Germany in 1939 in the occupation and partitioning of Poland. The Soviet leadership refused to endorse either the Allies or the Axis from 1939 to 1941, as it called the Allied-Axis conflict an "imperialist war".[39]

Stalin had studied Hitler, including reading Mein Kampf, and from it knew of Hitler's motives for destroying the Soviet Union.[40] As early as in 1933, the Soviet leadership voiced its concerns with the alleged threat of a potential German invasion of the country should Germany attempt a conquest of Lithuania, Latvia, or Estonia, and in December 1933 negotiations began for the issuing of a joint Polish-Soviet declaration guaranteeing the sovereignty of the three Baltic countries.[41] However, Poland withdrew from the negotiations following German and Finnish objections.[41] The Soviet Union and Germany at this time competed with each other for influence in Poland.[42]

On 20 August 1939, forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics under General Georgy Zhukov, together with the People's Republic of Mongolia eliminated the threat of conflict in the east with a victory over Imperial Japan at the Battle of Khalkhin Gol in eastern Mongolia.

On the same day, Soviet party leader Joseph Stalin received a telegram from German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, suggesting that German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop fly to Moscow for diplomatic talks. (After receiving a lukewarm response throughout the spring and summer, Stalin abandoned attempts for a better diplomatic relationship with France and the United Kingdom.)[43]

On 23 August, Ribbentrop and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov signed the non-aggression pact including secret protocols dividing Eastern Europe into defined "spheres of influence" for the two regimes, and specifically concerning the partition of the Polish state in the event of its "territorial and political rearrangement".[44]

On 15 September 1939, Stalin concluded a durable ceasefire with Japan, to take effect the following day (it would be upgraded to a non-aggression pact in April 1941).[45] The day after that, 17 September, Soviet forces invaded Poland from the east. Although some fighting continued until 5 October, the two invading armies held at least one joint military parade on 25 September, and reinforced their non-military partnership with the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation on 28 September. German and Soviet cooperation against Poland in 1939 has been described as co-belligerence.[46][47]

On 30 November, the Soviet Union attacked Finland, for which it was expelled from the League of Nations. In the following year of 1940, while the world's attention was focused upon the German invasion of France and Norway,[48] the USSR militarily[49] occupied and annexed Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania[50] as well as parts of Romania.

German-Soviet treaties were brought to an end by the German surprise attack on the USSR on 22 June 1941. After the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Stalin endorsed the Western Allies as part of a renewed popular front strategy against Germany and called for the international communist movement to make a coalition with all those who opposed the Nazis.[39] The Soviet Union soon entered in alliance with the United Kingdom. Following the USSR, a number of other communist, pro-Soviet or Soviet-controlled forces fought against the Axis powers during the Second World War. They were as follows: the Albanian National Liberation Front, the Chinese Red Army, the Greek National Liberation Front, the Hukbalahap, the Malayan Communist Party, the People's Republic of Mongolia, the Polish People's Army, the Tuvan People's Republic (annexed by the Soviet Union in 1944),[51] the Viet Minh and the Yugoslav Partisans.

The Soviet Union intervened against Japan and its client state in Manchuria in 1945, cooperating with the Nationalist Government of China and the Nationalist Party led by Chiang Kai-shek; though also cooperating, preferring, and encouraging the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Zedong to take effective control of Manchuria after expelling Japanese forces.[52]

United States

War justifications

The United States had indirectly supported Britain's war effort against Germany up to 1941 and declared its opposition to territorial aggrandizement. Materiel support to Britain was provided while the U.S. was officially neutral via the Lend-Lease Act starting in 1941.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill in August 1941 promulgated the Atlantic Charter that pledged commitment to achieving "the final destruction of Nazi tyranny".[53] Signing the Atlantic Charter, and thereby joining the "United Nations" was the way a state joined the Allies, and also became eligible for membership in the United Nations world body that formed in 1945.

The US strongly supported the Nationalist Government in China in its war with Japan, and provided military equipment, supplies, and volunteers to the Nationalist Government of China to assist in its war effort.[54] In December 1941 Japan opened the war with its attack on Pearl Harbor, the US declared war on Japan, and Japan's allies Germany and Italy declared war on the US, bringing the US into World War II.

The US played a central role in liaising among the Allies and especially among the Big Four.[55] At the Arcadia Conference in December 1941, shortly after the US entered the war, the US and Britain established a Combined Chiefs of Staff, based in Washington, which deliberated the military decisions of both the US and Britain.

History

On 8 December 1941, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Congress declared war on Japan at the request of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This was followed by Germany and Italy declaring war on the United States on 11 December, bringing the country into the European theatre.

The US led Allied forces in the Pacific theatre against Japanese forces from 1941 to 1945. From 1943 to 1945, the US also led and coordinated the Western Allies' war effort in Europe under the leadership of General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor followed by Japan's swift attacks on Allied locations throughout the Pacific, resulted in major US losses in the first several months in the war, including losing control of the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island and several Aleutian islands including Attu and Kiska to Japanese forces. American naval forces attained some early successes against Japan. One was the bombing of Japanese industrial centres in the Doolittle Raid. Another was repelling a Japanese invasion of Port Moresby in New Guinea during the Battle of the Coral Sea.[56]

A major turning point in the Pacific War was the Battle of Midway where American naval forces were outnumbered by Japanese forces that had been sent to Midway to draw out and destroy American aircraft carriers in the Pacific and seize control of Midway that would place Japanese forces in proximity to Hawaii.[57] However American forces managed to sink four of Japan's six large aircraft carriers that had initiated the attack on Pearl Harbor along with other attacks on Allied forces. Afterwards, the US began an offensive against Japanese-captured positions. The Guadalcanal Campaign from 1942 to 1943 was a major contention point where Allied and Japanese forces struggled to gain control of Guadalcanal.

Colonies and dependencies

In the Americas and the Pacific

The United States held multiple dependencies in the Americas, such as Alaska, the Panama Canal Zone, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

In the Pacific it held multiple island dependencies such as American Samoa, Guam, Hawaii, Midway Islands, Wake Island and others. These dependencies were directly involved in the Pacific campaign of the war.

In Asia

The Commonwealth of the Philippines was a sovereign protectorate referred to as an "associated state" of the United States. From late 1941 to 1944, the Philippines was occupied by Japanese forces, who established the Second Philippine Republic as a client state that had nominal control over the country.

China

In the 1920s the Soviet Union provided military assistance to the Kuomintang, or the Nationalists, and helped reorganize their party along Leninist lines: a unification of party, state, and army. In exchange the Nationalists agreed to let members of the Chinese Communist Party join the Nationalists on an individual basis. However, following the nominal unification of China at the end of the Northern Expedition in 1928, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek purged leftists from his party and fought against the revolting Chinese Communist Party, former warlords, and other militarist factions.

A fragmented China provided easy opportunities for Japan to gain territories piece by piece without engaging in total war. Following the 1931 Mukden Incident, the puppet state of Manchukuo was established. Throughout the early to mid-1930s, Chiang's anti-communist and anti-militarist campaigns continued while he fought small, incessant conflicts against Japan, usually followed by unfavorable settlements and concessions after military defeats.

In 1936 Chiang was forced to cease his anti-communist military campaigns after his kidnap and release by Zhang Xueliang, and reluctantly formed a nominal alliance with the Communists, while the Communists agreed to fight under the nominal command of the Nationalists against the Japanese. Following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 7 July 1937, China and Japan became embroiled in a full-scale war. The Soviet Union, wishing to keep China in the fight against Japan, supplied China with military assistance until 1941, when it signed a non-aggression pact with Japan.

In December 1941 after the attack on Pearl Harbor, China formally declared war on Japan, as well as Germany and Italy. As part of the war's Pacific theater, China became the only member of the Allies to commit more troops than one of the Big Three,[58] exceeding even the number of Soviet troops on the Eastern Front.[59]

Continuous clashes between the Communists and Nationalists behind enemy lines cumulated in a major military conflict between these two former allies that effectively ended their cooperation against the Japanese, and China had been divided between the internationally recognized Nationalist China under the leadership of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Communist China under the leadership of Mao Zedong until the Japanese surrendered in 1945.

Factions

Nationalists

Prior to the alliance of Germany and Italy to Japan, the Nationalist Government held close relations with both Germany and Italy. In the early 1930s, Sino-German cooperation existed between the Nationalist Government and Germany in military and industrial matters. Nazi Germany provided the largest proportion of Chinese arms imports and technical expertise. Relations between the Nationalist Government and Italy during the 1930s varied, however even after the Nationalist Government followed League of Nations sanctions against Italy for its invasion of Ethiopia, the international sanctions proved unsuccessful, and relations between the Fascist government in Italy and the Nationalist Government in China returned to normal shortly afterwards.[60]

Up until 1936, Mussolini had provided the Nationalists with Italian military air and naval missions to help the Nationalists fight against Japanese incursions and communist insurgents.[60] Italy also held strong commercial interests and a strong commercial position in China supported by the Italian concession in Tianjin.[60] However, after 1936 the relationship between the Nationalist Government and Italy changed due to a Japanese diplomatic proposal to recognize the Italian Empire that included occupied Ethiopia within it in exchange for Italian recognition of Manchukuo, Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano accepted this offer by Japan, and on 23 October 1936 Japan recognized the Italian Empire and Italy recognized Manchukuo, as well as discussing increasing commercial links between Italy and Japan.[61]

The Nationalist Government held close relations with the United States. The United States opposed Japan's invasion of China in 1937 that it considered an illegal violation of China's sovereignty, and offered the Nationalist Government diplomatic, economic, and military assistance during its war against Japan. In particular, the United States sought to bring the Japanese war effort to a complete halt by imposing a full embargo on all trade between the United States to Japan, Japan was dependent on the United States for 80 per cent of its petroleum, resulting in an economic and military crisis for Japan that could not continue its war effort with China without access to petroleum.[62] In November 1940, American military aviator Claire Lee Chennault upon observing the dire situation in the air war between China and Japan, set out to organize a volunteer squadron of American fighter pilots to fight alongside the Chinese against Japan, known as the Flying Tigers.[63] US President Franklin D. Roosevelt accepted dispatching them to China in early 1941.[63] However, they only became operational shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Soviet Union recognised the Republic of China but urged reconciliation with the Chinese Communist Party and inclusion of Communists in the government.[64] The Soviet Union also urged military and cooperation between Nationalist China and Communist China during the war.[64]

Even though China had been fighting the longest among all the Allied powers, it only officially joined the Allies after the attack on Pearl Harbor, on 7 December 1941. China fought the Japanese Empire before joining the Allies in the Pacific War. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek thought Allied victory was assured with the entrance of the United States into the war, and he declared war on Germany and the other Axis states. However, Allied aid remained low because the Burma Road was closed and the Allies suffered a series of military defeats against Japan early on in the campaign. General Sun Li-jen led the R.O.C. forces to the relief of 7,000 British forces trapped by the Japanese in the Battle of Yenangyaung. He then reconquered North Burma and re-established the land route to China by the Ledo Road. But the bulk of military aid did not arrive until the spring of 1945. More than 1.5 million Japanese troops were trapped in the China Theatre, troops that otherwise could have been deployed elsewhere if China had collapsed and made a separate peace.

Communists

Communist China had been tacitly supported by the Soviet Union since the 1920s: though the Soviet Union diplomatically recognised the Republic of China, Joseph Stalin supported cooperation between the Nationalists and the Communists—including pressuring the Nationalist Government to grant the Communists state and military positions in the government.[64] This was continued into the 1930s that fell in line with the Soviet Union's subversion policy of popular fronts to increase communists' influence in governments.[64]

The Soviet Union urged military and cooperation between Communist China and Nationalist China during China's war against Japan.[64] Initially Mao Zedong accepted the demands of the Soviet Union and in 1938 had recognized Chiang Kai-shek as the "leader" of the "Chinese people".[65] In turn, the Soviet Union accepted Mao's tactic of "continuous guerilla warfare" in the countryside that involved a goal of extending the Communist bases, even if it would result in increased tensions with the Nationalists.[65]

After the breakdown of their cooperation with the Nationalists in 1941, the Communists prospered and grew as the war against Japan dragged on, building up their sphere of influence wherever opportunities were presented, mainly through rural mass organizations, administrative, land and tax reform measures favoring poor peasants; while the Nationalists attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence by military blockade and fighting the Japanese at the same time.[66]

The Communist Party's position in China was boosted further upon the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945 against the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo and the Japanese Kwantung Army in China and Manchuria. Upon the intervention of the Soviet Union against Japan in World War II in 1945, Mao Zedong in April and May 1945 had planned to mobilize 150,000 to 250,000 soldiers from across China to work with forces of the Soviet Union in capturing Manchuria.[67]

Other affiliated state combatants

Albania

Albania was retroactively recognized as an "Associated Power" at the 1946 Paris conference[68] and officially signed the treaty ending WWII between the "Allied and Associated Powers" and Italy in Paris, on 10 February 1947.[69][70]

Australia

Australia was a sovereign Dominion under the Australian monarchy, as per the Statute of Westminster 1931. At the start of the war Australia followed Britain's foreign policies and accordingly declared war against Germany on 3 September 1939. Australian foreign policy became more independent after the Australian Labor Party formed government in October 1941, and Australia separately declared war against Finland, Hungary and Romania on 8 December 1941 and against Japan the next day.[71]

Belgium

Before the war, Belgium had pursued a policy of neutrality and only became an Allied member after being invaded by Germany on 10 May 1940. During the ensuing fighting, Belgian forces fought alongside French and British forces against the invaders. While the British and French were struggling against the fast German advance elsewhere on the front, the Belgian forces were pushed into a pocket to the north. On 28 May, the King Leopold III surrendered himself and his military to the Germans, having decided the Allied cause was lost.

The legal Belgian government was reformed as a government in exile in London. Belgian troops and pilots continued to fight on the Allied side as the Free Belgian Forces. Belgium itself was occupied, but a sizeable Resistance was formed and was loosely coordinated by the government in exile and other Allied powers.

British and Canadian troops arrived in Belgium in September 1944 and the capital, Brussels, was liberated on 6 September. Because of the Ardennes Offensive, the country was only fully liberated in early 1945.

Colonies and dependencies

Belgium held the colony of the Belgian Congo and the League of Nations mandate of Ruanda-Urundi. The Belgian Congo was not occupied and remained loyal to the Allies as an important economic asset while its deposits of uranium were useful to the Allied efforts to develop the atomic bomb. Troops from the Belgian Congo participated in the East African Campaign against the Italians. The colonial Force Publique also served in other theatres including Madagascar, the Middle-East, India and Burma within British units.

Brazil

Initially, Brazil maintained a position of neutrality, trading with both the Allies and the Axis, while Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas's quasi-Fascist policies indicated a leaning toward the Axis powers.[citation needed] However, as the war progressed, trade with the Axis countries became almost impossible and the United States initiated forceful diplomatic and economic efforts to bring Brazil onto the Allied side.[citation needed]

At the beginning of 1942, Brazil permitted the United States to set up air bases on its territory, especially in Natal, strategically located at the easternmost corner of the South American continent, and on 28 January the country severed diplomatic relations with Germany, Japan and Italy. After that, 36 Brazilian merchant ships were sunk by the German and Italian navies, which led the Brazilian government to declare war against Germany and Italy on 22 August 1942.

Brazil then sent a 25,700 strong Expeditionary Force to Europe that fought mainly on the Italian front, from September 1944 to May 1945. Also, the Brazilian Navy and Air Force acted in the Atlantic Ocean from the middle of 1942 until the end of the war. Brazil was the only South American country to send troops to fight in the European theatre in the Second World War.

Canada

Canada was a sovereign Dominion under the Canadian monarchy, as per the Statute of Westminster 1931. In a symbolic statement of autonomous foreign policy Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King delayed parliament's vote on a declaration of war for seven days after Britain had declared war. Canada was the last member of the Commonwealth to declare war on Germany on 10 September 1939.[72]

Cuba

Because of Cuba's geographical position at the entrance of the Gulf of Mexico, Havana's role as the principal trading port in the West Indies, and the country's natural resources, Cuba was an important participant in the American Theater of World War II, and subsequently one of the greatest beneficiaries of the United States' Lend-Lease program. Cuba declared war on the Axis powers in December 1941,[73] making it one of the first Latin American countries to enter the conflict, and by the war's end in 1945 its military had developed a reputation as being the most efficient and cooperative of all the Caribbean states.[74] On 15 May 1943, the Cuban patrol boat CS-13 sank the German submarine U-176.[75][76]

Czechoslovakia

In 1938, with the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia, the United Kingdom, and France sought to resolve German irredentist claims to the Sudetenland region. As a result, the incorporation of the Sudetenland into Germany began on 1 October 1938. Additionally, a small northeastern part of the border region known as Trans-Olza was occupied by and annexed to Poland. Further, by the First Vienna Award, Hungary received southern territories of Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia.

A Slovak State was proclaimed on 14 March 1939, and the next day Hungary occupied and annexed the remainder of Carpathian Ruthenia, and the German Wehrmacht moved into the remainder of the Czech Lands. On 16 March 1939 the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed after negotiations with Emil Hácha, who remained technically head of state with the title of State President. After a few months, former Czechoslovak President Beneš organized a committee in exile and sought diplomatic recognition as the legitimate government of the First Czechoslovak Republic. The committee's success in obtaining intelligence and coordinating actions by the Czechoslovak resistance led first Britain and then the other Allies to recognize it in 1941. In December 1941 the Czechoslovak government-in-exile declared war on the Axis powers. Czechoslovakian military units took part in the war.

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic was one of the very few countries willing to accept mass Jewish immigration during World War II. At the Évian Conference, it offered to accept up to 100,000 Jewish refugees.[77] The DORSA (Dominican Republic Settlement Association) was formed with the assistance of the JDC, and helped settle Jews in Sosúa, on the northern coast. About 700 European Jews of Ashkenazi Jewish descent reached the settlement where each family received 33 hectares (82 acres) of land, 10 cows (plus 2 additional cows per children), a mule and a horse, and a US$10,000 loan (equivalent to about $207,000 in 2023[78]) at 1% interest.[79][80]

The Dominican Republic officially declared war on the Axis powers on 11 December 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor. However, the Caribbean state had already been engaged in war actions since before the formal declaration of war. Dominican sailboats and schooners had been attacked on previous occasions by German submarines as, highlighting the case of the 1,993-ton merchant ship, San Rafael, which was making a trip from Tampa, Florida to Kingston, Jamaica, when 80 miles away from its final destination, it was torpedoed by the German submarine U-125, causing the commander to order the ship abandoned. Although the crew of San Rafael managed to escape the event, it would be remembered by the Dominican press as a sign of the "infamy of the German submarines and the danger they represented in the Caribbean".[attribution needed][81]

Recently, due to a research work carried out by the Embassy of the United States of America in Santo Domingo and the Institute of Dominican Studies of the City of New York (CUNY), documents of the Department of Defense were discovered in which it was confirmed that around 340 men and women of Dominican origin were part of the US Armed Forces during the World War II. Many of them received medals and other recognitions for their outstanding actions in combat.[82]

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian Empire was invaded by Italy on 3 October 1935. On 2 May 1936, Emperor Haile Selassie I fled into exile, just before the Italian occupation on 7 May. After the outbreak of World War II, the Ethiopian government-in-exile cooperated with the British during the British Invasion of Italian East Africa beginning in June 1940. Haile Selassie returned to his rule on 18 January 1941. Ethiopia declared war on Germany, Italy and Japan in December 1942.

Greece

Greece was invaded by Italy on 28 October 1940 and subsequently joined the Allies. The Greek Army managed to stop the Italian offensive from Italy's protectorate of Albania, and Greek forces pushed Italian forces back into Albania. However, after the German invasion of Greece in April 1941, German forces managed to occupy mainland Greece and, a month later, the island of Crete. The Greek government went into exile, while the country was placed under a puppet government and divided into occupation zones run by Italy, Germany and Bulgaria.

From 1941, a strong resistance movement appeared, chiefly in the mountainous interior, where it established a "Free Greece" by mid-1943. Following the Italian capitulation in September 1943, the Italian zone was taken over by the Germans. Axis forces left mainland Greece in October 1944, although some Aegean islands, notably Crete, remained under German occupation until the end of the war.

Luxembourg

Before the war, Luxembourg had pursued a policy of neutrality and only became an Allied member after being invaded by Germany on 10 May 1940. The government in exile fled, winding up in England. It made Luxembourgish language broadcasts to the occupied country on BBC radio.[83] In 1944, the government in exile signed a treaty with the Belgian and Dutch governments, creating the Benelux Economic Union and also signed into the Bretton Woods system.

Mexico

Mexico declared war on Germany in 1942 after German submarines attacked the Mexican oil tankers Potrero del Llano and Faja de Oro that were transporting crude oil to the United States. These attacks prompted President Manuel Ávila Camacho to declare war on the Axis powers.

Mexico formed Escuadrón 201 fighter squadron as part of the Fuerza Aérea Expedicionaria Mexicana (FAEM—"Mexican Expeditionary Air Force"). The squadron was attached to the 58th Fighter Group of the United States Army Air Forces and carried out tactical air support missions during the liberation of the main Philippine island of Luzon in the summer of 1945.[84]

Some 300,000 Mexican citizens went to the United States to work on farms and factories. Some 15,000 U.S. nationals of Mexican origin and Mexican residents in the US enrolled in the US Armed Forces and fought in various fronts around the world.[85]

Netherlands

The Netherlands became an Allied member after being invaded on 10 May 1940 by Germany. During the ensuing campaign, the Netherlands were defeated and occupied by Germany. The Netherlands was liberated by Canadian, British, American and other allied forces during the campaigns of 1944 and 1945. The Princess Irene Brigade, formed from escapees from the German invasion, took part in several actions in 1944 in Arromanches and in 1945 in the Netherlands. Navy vessels saw action in the British Channel, the North Sea and the Mediterranean, generally as part of Royal Navy units. Dutch airmen flying British aircraft participated in the air war over Germany.

Colonies and dependencies

The Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) was the principal Dutch colony in Asia, and was seized by Japan in 1942. During the Dutch East Indies Campaign, the Netherlands played a significant role in the Allied effort to halt the Japanese advance as part of the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command. The ABDA fleet finally encountered the Japanese surface fleet at the Battle of Java Sea, at which Doorman gave the order to engage. During the ensuing battle the ABDA fleet suffered heavy losses, and was mostly destroyed after several naval battles around Java; the ABDA Command was later dissolved. The Japanese finally occupied the Dutch East Indies in February–March 1942. Dutch troops, aircraft and escaped ships continued to fight on the Allied side and also mounted a guerrilla campaign in Timor.

New Zealand

New Zealand was a sovereign Dominion under the New Zealand monarchy, as per the Statute of Westminster 1931. It quickly entered World War II, officially declaring war on Germany on 3 September 1939, just hours after Britain.[86] Unlike Australia, which had felt obligated to declare war, as it also had not ratified the Statute of Westminster, New Zealand did so as a sign of allegiance to Britain, and in recognition of Britain's abandonment of its former appeasement policy, which New Zealand had long opposed. This led to then Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage declaring two days later:

With gratitude for the past and confidence in the future we range ourselves without fear beside Britain. Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand. We are only a small and young nation, but we march with a union of hearts and souls to a common destiny.[87]

Norway

Because of its strategic location for control of the sea lanes in the North Sea and the Atlantic, both the Allies and Germany worried about the other side gaining control of the neutral country. Germany ultimately struck first with Operation Weserübung on 9 April 1940, resulting in the two-month-long Norwegian Campaign, which ended in a German victory and their war-long occupation of Norway.

Units of the Norwegian Armed Forces evacuated from Norway or raised abroad continued participating in the war from exile.

The Norwegian merchant fleet, then the fourth largest in the world, was organized into Nortraship to support the Allied cause. Nortraship was the world's largest shipping company, and at its height operated more than 1000 ships.

Norway was neutral when Germany invaded, and it is not clear when Norway became an Allied country. Great Britain, France and Polish forces in exile supported Norwegian forces against the invaders but without a specific agreement. Norway's cabinet signed a military agreement with Britain on 28 May 1941. This agreement allowed all Norwegian forces in exile to operate under UK command. Norwegian troops in exile should primarily be prepared for the liberation of Norway, but could also be used to defend Britain. At the end of the war German forces in Norway surrendered to British officers on 8 May and allied troops occupied Norway until 7 June.[88]

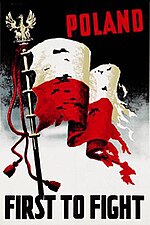

Poland

The Invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, started the war in Europe, and the United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany on 3 September. Poland fielded the third biggest army among the European Allies, after the Soviet Union and United Kingdom, but before France.[89]

Polish Army suffered a series of defeats in the first days of the invasion. The Soviet Union unilaterally considered the flight to Romania of President Ignacy Mościcki and Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły on 17 September as evidence of debellatio causing the extinction of the Polish state, and consequently declared itself allowed to invade Poland starting from the same day.[90] However, the Red Army had invaded the Second Polish Republic several hours before the Polish president fled to Romania. The Soviets invaded on 17 September at 3 a.m.,[91] while president Mościcki crossed the Polish-Romanian border at 21:45 on the same day.[92]

The Polish military continued to fight against both the Germans and the Soviets, and the last major battle of the war, the Battle of Kock, ended at 1 a.m. on 6 October 1939 with the Independent Operational Group "Polesie", a field army, surrendering due to lack of ammunition. The country never officially surrendered to Nazi Germany, nor to the Soviet Union, and continued the war effort under the Polish government-in-exile.

The formation of the Polish armed forces in France began as early as September 1939. By June 1940, their numbers had reached 85,000 soldiers.[93] These forces took part in the Norwegian campaign and the Battle of France. After the defeat of France, the reconstitution of the Polish army had to start from scratch. Polish pilots played a key role in the Battle of Britain, separate Polish units took part in the North African Campaign. After the conclusion of the Polish-Soviet agreement on July 30, 1941, the formation of the Polish army in the USSR (II Corps) also began.[94] The II Corps, numbering 83,000 along with civilians, began to be evacuated from the USSR in mid-1942.[95] It later took part in the fighting in Italy.

After breaking off relations with the Polish government, the Soviet Union began forming its own Polish communist government and its armed forces in mid-1943, from which the 1st Polish Army, under Zygmunt Berling, was formed on March 16, 1944.[96] That army was fighting on the eastern front, alongside the Soviet forces, including the Battle of Berlin, the closing battle of the European theater of war.

The Home Army, loyal to the London-based government and the largest underground force in Europe, as well other smaller resistance organizations in occupied Poland provided intelligence to the Allies and led to uncovering of Nazi war crimes (i.e., death camps).

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic contacts with Germany on 11 September 1939, and with Japan in October 1941. The Saudis provided the Allies with large supplies of oil. Diplomatic relations with the United States were established in 1943. King Abdul Aziz Al-Saud was a personal friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Americans were then allowed to build an air force base near Dhahran.[97] Saudi Arabia declared war on Germany and Japan in 1945.[98]

South Africa

South Africa was a sovereign Dominion under the South African monarchy, as per the Statute of Westminster 1931. South Africa held authority over the mandate of South-West Africa. Due to significant pro-German feeling and the presence of fascist sympathizers within the Afrikaner nationalist movement (such as the Grey Shirts and the Ossewabrandwag), South Africa's entry into the war was politically divisive.[99] Initially the government of J. B. M. Hertzog tried to maintain official neutrality after the outbreak of war. This caused a revolt by the governing United Party caucus which voted against Hertzog's position on the war and resulted in Hertzog's coalition partner, Jan Smuts, forming a new government and becoming prime minister. Smuts was then able to lead the country into war on the side of the Allies.[100]

Around 334,000 South Africans volunteered to fight in the war with 11,023 recorded wartime deaths.[101]

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia entered the war on the Allied side after the invasion of Axis powers on 6 April 1941. The Royal Yugoslav Army was thoroughly defeated in less than two weeks and the country was occupied starting on 18 April. The Italian-backed Croatian fascist leader Ante Pavelić declared the Independent State of Croatia before the invasion was over. King Peter II and much of the Yugoslavian government had left the country. In the United Kingdom, they joined numerous other governments in exile from Nazi-occupied Europe. Beginning with the uprising in Herzegovina in June 1941, there was continuous anti-Axis resistance in Yugoslavia until the end of the war.

Resistance factions

Before the end of 1941, the anti-Axis resistance movement split between the royalist Chetniks and the communist Yugoslav Partisans of Josip Broz Tito who fought both against each other during the war and against the occupying forces. The Yugoslav Partisans managed to put up considerable resistance to the Axis occupation, forming various liberated territories during the war. In August 1943, there were over 30 Axis divisions on the territory of Yugoslavia, not including the forces of the Croatian puppet state and other quisling formations.[102] In 1944, the leading Allied powers persuaded Tito's Yugoslav Partisans and the royalist Yugoslav government led by Prime Minister Ivan Šubašić to sign the Treaty of Vis that created the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Partisans

The Partisans were a major Yugoslav resistance movement against the Axis occupation and partition of Yugoslavia. Initially, the Partisans were in rivalry with the Chetniks over control of the resistance movement. However, the Partisans were recognized by both the Eastern and Western Allies as the primary resistance movement in 1943. After that, their strength increased rapidly, from 100,000 at the beginning of 1943 to over 648,000 in September 1944. In 1945 they were transformed into the Yugoslav army, organized in four field armies with 800,000[103] fighters.

Chetniks

The Chetniks, the short name given to the movement titled the Yugoslav Army of the Fatherland, were initially a major Allied Yugoslav resistance movement. However, due to their royalist and anti-communist views, Chetniks were considered to have begun collaborating with the Axis as a tactical move to focus on destroying their Partisan rivals. The Chetniks presented themselves as a Yugoslav movement, but were primarily a Serb movement. They reached their peak in 1943 with 93,000 fighters.[104] Their major contribution was Operation Halyard in 1944. In collaboration with the OSS, 413 Allied airmen shot down over Yugoslavia were rescued and evacuated.

Client and occupied states

British

Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt was nominally sovereign since 1922 but effectively remained in the British sphere of influence; the British Mediterranean Fleet was stationed in Alexandria while British Army forces were based in the Suez Canal zone. Egypt was a neutral country for most of World War II, but the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936 permitted British forces in Egypt to defend the Suez Canal. The United Kingdom controlled Egypt and used it as a major base for Allied operations throughout the region, especially the battles in North Africa against Italy and Germany. Its highest priorities were control of the Eastern Mediterranean, and especially keeping the Suez Canal open for merchant ships and for military connections with India and Australia.[105][page needed]

Egypt faced an Axis campaign led by Italian and German forces during the war. British frustration over King Farouk's reign over Egypt resulted in the Abdeen Palace incident of 1942 where British Army forces surrounded the royal palace and demanded a new government be established, nearly forcing the abdication of Farouk until he submitted to British demands. The Kingdom of Egypt joined the United Nations on 24 February 1945.[106]

India (British Raj)

At the outbreak of World War II, the British Indian Army numbered 205,000 men. Later during World War II, the Indian Army became the largest all-volunteer force in history, rising to over 2.5 million men in size.[107] These forces included tank, artillery and airborne forces.

Indian soldiers earned 30 Victoria Crosses during the Second World War. During the war, India suffered more civilian casualties than the United Kingdom, with the Bengal famine of 1943 estimated to have killed at least 2–3 million people.[108] In addition, India suffered 87,000 military casualties, more than any Crown colony but fewer than the United Kingdom, which suffered 382,000 military casualties.

Burma

Burma was a British colony at the start of World War II. It was later invaded by Japanese forces and that contributed to the Bengal Famine of 1943. For the native Burmese, it was an uprising against colonial rule, so some fought on the Japanese's side, but most minorities fought on the Allies side.[109] Burma also contributed resources such as rice and rubber.

Soviet sphere

Bulgaria

After a period of neutrality, Bulgaria joined the Axis powers from 1941 to 1944. The Orthodox Church and others convinced King Boris to not allow the Bulgarian Jews to be exported to concentration camps. The king died shortly afterwards, suspected of being poisoned after a visit to Germany. Bulgaria abandoned the Axis and joined the Allies when the Soviet Union invaded, offering no resistance to the incoming forces. Bulgarian troops then fought alongside Soviet Army in Yugoslavia, Hungary and Austria. In the 1947 peace treaties, Bulgaria gained a small area near the Black Sea from Romania, making it the only former German ally to gain territory from WWII.

Central Asian and Caucasian Republics

Among the Soviet forces during World War II, millions of troops were from the Soviet Central Asian Republics. They included 1,433,230 soldiers from Uzbekistan,[110] more than 1 million from Kazakhstan,[111] and more than 700,000 from Azerbaijan,[112] among other Central Asian Republics.

Mongolia

Mongolia fought against Japan during the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in 1939 and the Soviet–Japanese War in August 1945 to protect its independence and to liberate Southern Mongolia from Japan and China. Mongolia had been in the Soviet sphere of influence since the 1920s.

Poland

By 1944, Poland entered the Soviet sphere of influence with the establishment of Władysław Gomułka's communist regime. Polish forces fought alongside Soviet forces against Germany.

Romania

Romania had initially been a member of the Axis powers but switched allegiance upon facing invasion by the Soviet Union. In a radio broadcast to the Romanian people and army on the night of 23 August 1944 King Michael issued a cease-fire,[113] proclaimed Romania's loyalty to the Allies, announced the acceptance of an armistice (to be signed on 12 September)[114] offered by the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States, and declared war on Germany.[115] The coup accelerated the Red Army's advance into Romania, but did not avert a rapid Soviet occupation and capture of about 130,000 Romanian soldiers, who were transported to the Soviet Union where many perished in prison camps.

The armistice was signed three weeks later on 12 September 1944, on terms virtually dictated by the Soviet Union.[113] Under the terms of the armistice, Romania announced its unconditional surrender[116] to the USSR and was placed under the occupation of the Allied forces with the Soviet Union as their representative, in control of the media, communication, post, and civil administration behind the front.[113]

Romanian troops then fought alongside the Soviet Army until the end of the war, reaching as far as Slovakia and Germany.

Tuva

The Tuvan People's Republic was a partially recognized state founded from the former Tuvan protectorate of Imperial Russia. It was a client state of the Soviet Union and was annexed into the Soviet Union in 1944.

Co-belligerent state combatants

Finland

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

Following the Moscow Armistice of September 1944, Finland fought on the side of the Allies against Axis forces until April 1945 in the Lapland War.

Italy

Italy initially had been a leading member of the Axis powers. However, after facing multiple military losses, including the loss of all of Italy's colonies to advancing Allied forces, Duce Benito Mussolini was deposed and arrested in July 1943 by order of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy in co-operation with members of the Grand Council of Fascism who viewed Mussolini as having led Italy to ruin by allying with Germany in the war. Victor Emmanuel III dismantled the remaining apparatus of the Fascist regime and appointed Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio as Prime Minister of Italy. On 8 September 1943, Italy signed the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies, ending Italy's war with the Allies and ending Italy's participation with the Axis powers. Expecting immediate German retaliation, Victor Emmanuel III and the Italian government relocated to southern Italy under Allied control. Germany viewed the Italian government's actions as an act of betrayal, and German forces immediately occupied all Italian territories outside of Allied control,[117] in some cases even massacring Italian troops.

Italy became a co-belligerent of the Allies, and the Italian Co-Belligerent Army was created to fight against the German occupation of Northern Italy, where German paratroopers rescued Mussolini from arrest and he was placed in charge of a German puppet state known as the Italian Social Republic (RSI). Italy descended into civil war until the end of hostilities after his deposition and arrest, with Fascists loyal to him allying with German forces and helping them against the Italian armistice government and partisans.[118]

Legacy

Charter of the United Nations

The Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942, signed by the Four Policemen – the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union and China – and 22 other nations laid the groundwork for the future of the United Nations.[119][120] At the Potsdam Conference of July–August 1945, Roosevelt's successor, Harry S. Truman, proposed that the foreign ministers of China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States "should draft the peace treaties and boundary settlements of Europe", which led to the creation of the Council of Foreign Ministers of the "Big Five", and soon thereafter the establishment of those states as the permanent members of the UNSC.[121]

The Charter of the United Nations was agreed to during the war at the United Nations Conference on International Organization, held between April and July 1945. The Charter was signed by 50 states on 26 June (Poland had its place reserved and later became the 51st "original" signatory),[citation needed] and was formally ratified shortly after the war on 24 October 1945. In 1944, the United Nations was formulated and negotiated among the delegations from the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States and China at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference[122][123] where the formation and the permanent seats (for the "Big Five", China, France, the UK, US, and USSR) of the United Nations Security Council were decided. The Security Council met for the first time in the immediate aftermath of war on 17 January 1946.[124]

These are the original 51 signatories (UNSC permanent members are asterisked):

Argentine Republic

Argentine Republic Commonwealth of Australia

Commonwealth of Australia Kingdom of Belgium

Kingdom of Belgium Republic of Bolivia

Republic of Bolivia United States of Brazil

United States of Brazil Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic Dominion of Canada

Dominion of Canada Republic of Chile

Republic of Chile Republic of China*

Republic of China* Republic of Colombia

Republic of Colombia Republic of Costa Rica

Republic of Costa Rica Republic of Cuba

Republic of Cuba Czechoslovak Republic

Czechoslovak Republic Kingdom of Denmark

Kingdom of Denmark Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Republic of Ecuador

Republic of Ecuador Kingdom of Egypt

Kingdom of Egypt Republic of El Salvador

Republic of El Salvador Ethiopian Empire

Ethiopian Empire French Republic*

French Republic* Kingdom of Greece

Kingdom of Greece Republic of Guatemala

Republic of Guatemala Republic of Haiti

Republic of Haiti Republic of Honduras

Republic of Honduras Indian Empire

Indian Empire Imperial Kingdom of Iran

Imperial Kingdom of Iran Kingdom of Iraq

Kingdom of Iraq Lebanese Republic

Lebanese Republic Republic of Liberia

Republic of Liberia Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg United Mexican States

United Mexican States Kingdom of the Netherlands

Kingdom of the Netherlands Dominion of New Zealand

Dominion of New Zealand Republic of Nicaragua

Republic of Nicaragua Kingdom of Norway

Kingdom of Norway Republic of Panama

Republic of Panama Republic of Paraguay

Republic of Paraguay Republic of Peru

Republic of Peru Commonwealth of the Philippines

Commonwealth of the Philippines Republic of Poland

Republic of Poland Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Union of South Africa

Union of South Africa Syrian Republic

Syrian Republic Republic of Turkey

Republic of Turkey Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Union of Soviet Socialist Republics*

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics* United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland*

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland* United States of America*

United States of America* Oriental Republic of Uruguay

Oriental Republic of Uruguay United States of Venezuela

United States of Venezuela Democratic Federal Yugoslavia

Democratic Federal Yugoslavia

Cold War

Despite the successful creation of the United Nations, the alliance of the Soviet Union with the United States and with the United Kingdom ultimately broke down and evolved into the Cold War, which took place over the following half-century.[15][22]

Summary table

| Country | Declaration by United Nations | Declared war on the Axis | San Francisco Conference |

|---|---|---|---|

Timeline of allied nations entering the war

The following list denotes dates on which states declared war on the Axis powers, or on which an Axis power declared war on them. The Indian Empire had a status less independent than the Dominions.[125]

1939

Poland: 1 September 1939[126]

Poland: 1 September 1939[126] France: 3 September 1939[127] – On 22 June 1940, Vichy France under Marshal Pétain formally capitulated to Germany, and became neutral. This capitulation was denounced by General de Gaulle, who established the Free France government-in-exile, which continued to fight against Germany. This led to the Provisional Government of the French Republic, which was officially recognized by the other Allies as the legitimate government of France on 23 October 1944.[128] Pétain's 1940 surrender was also legally nullified, so France is considered an Ally throughout the war.[129]

France: 3 September 1939[127] – On 22 June 1940, Vichy France under Marshal Pétain formally capitulated to Germany, and became neutral. This capitulation was denounced by General de Gaulle, who established the Free France government-in-exile, which continued to fight against Germany. This led to the Provisional Government of the French Republic, which was officially recognized by the other Allies as the legitimate government of France on 23 October 1944.[128] Pétain's 1940 surrender was also legally nullified, so France is considered an Ally throughout the war.[129] United Kingdom: 3 September 1939[127]

United Kingdom: 3 September 1939[127]

Australia: 3 September 1939[130][132]

Australia: 3 September 1939[130][132] New Zealand: 3 September 1939[130][133]

New Zealand: 3 September 1939[130][133] Nepal: 4 September 1939[134]

Nepal: 4 September 1939[134] South Africa: 6 September 1939[106]

South Africa: 6 September 1939[106] Canada: 10 September 1939[106]

Canada: 10 September 1939[106] Sultanate of Muscat and Oman: 10 September 1939

Sultanate of Muscat and Oman: 10 September 1939

1940

Norway: 8 April 1940[106] – German invasion of a neutral country without declaration of war. The Allies supported Norway during the Norwegian Campaign. Norway did not officially join the Allies until later.[88][135]

Norway: 8 April 1940[106] – German invasion of a neutral country without declaration of war. The Allies supported Norway during the Norwegian Campaign. Norway did not officially join the Allies until later.[88][135] Denmark 9 April 1940 – German invasion without declaration of war.[136]