Circle of fifths

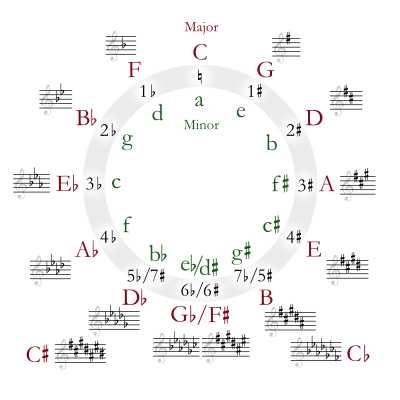

In music theory, the circle of fifths is a way of organizing pitches as a sequence of perfect fifths. Starting on a C, and using the standard system of tuning for Western music (12-tone equal temperament), the sequence is: C, G, D, A, E, B, F♯ (G♭), C♯ (D♭), G♯ (A♭), D♯ (E♭), A♯ (B♭), E♯ (F), C. This order places the most closely related key signatures adjacent to one another. It is usually illustrated in the form of a circle.

Twelve-tone equal temperament tuning divides each octave into twelve equivalent semitones, and the circle of fifths leads to a C seven octaves above the starting point. If the fifths are tuned with an exact ratio of 3:2 (the system of tuning known as just intonation), this is not the case (the circle does not "close").

Definition[edit]

The circle of fifths organizes pitches in a sequence of perfect fifths, generally shown as a circle with the pitches (and their corresponding keys) in clockwise order. It can be viewed in a counterclockwise direction as a circle of fourths. Harmonic progressions in Western music commonly use adjacent keys in this system, making it a useful reference for musical composition and harmony.[1]

The top of the circle shows the key of C Major, with no sharps or flats. Proceeding clockwise, the pitches ascend by fifths. The key signatures associated with those pitches change accordingly: the key of G has one sharp, the key of D has 2 sharps, and so on. Proceeding counterclockwise from the top of the circle, the notes change by descending fifths and the key signatures change accordingly: the key of F has one flat, the key of B♭ has 2 flats, and so on. Some keys (at the bottom of the circle) can be notated either in sharps or in flats.

Starting at any pitch and ascending by a fifth generates all tones before returning to the beginning pitch class (a pitch class consists of all of the notes indicated by a given letter regardless of octave—all "C"s, for example, belong to the same pitch class). Moving counterclockwise, the pitches descend by a fifth, but ascending by a perfect fourth will lead to the same note an octave higher (therefore in the same pitch class). Moving counter-clockwise from C could be thought of as descending by a fifth to F, or ascending by a fourth to F.

Structure and use[edit]

Diatonic key signatures[edit]

Each pitch can serve as the tonic of a major or minor key, and each of these keys will have a diatonic scale associated with it. The circle diagram shows the number of sharps or flats in each key signature, with the major key indicated by a capital letter and the minor key indicated by a lower-case letter. Major and minor keys that have the same key signature are referred to as relative major and relative minor of one another.

Modulation and chord progression[edit]

Tonal music often modulates to a new tonal center whose key signature differs from the original by only one flat or sharp. These closely-related keys are a fifth apart from each other and are therefore adjacent in the circle of fifths. Chord progressions also often move between chords whose roots are related by perfect fifth, making the circle of fifths useful in illustrating the "harmonic distance" between chords.

The circle of fifths is used to organize and describe the harmonic or tonal function of chords.[2] Chords can progress in a pattern of ascending perfect fourths (alternately viewed as descending perfect fifths) in "functional succession". This can be shown "...by the circle of fifths (in which, therefore, scale degree II is closer to the dominant than scale degree IV)".[3] In this view the tonic or tonal center is considered the end point of a chord progression derived from the circle of fifths.

According to Richard Franko Goldman's Harmony in Western Music, "the IV chord is, in the simplest mechanisms of diatonic relationships, at the greatest distance from I. In terms of the [descending] circle of fifths, it leads away from I, rather than toward it."[4] He states that the progression I–ii–V–I (an authentic cadence) would feel more final or resolved than I–IV–I (a plagal cadence). Goldman[5] concurs with Nattiez, who argues that "the chord on the fourth degree appears long before the chord on II, and the subsequent final I, in the progression I–IV–viio–iii–vi–ii–V–I", and is farther from the tonic there as well.[6] (In this and related articles, upper-case Roman numerals indicate major triads while lower-case Roman numerals indicate minor triads.)

Circle closure in non-equal tuning systems[edit]

Using the exact 3:2 ratio of frequencies to define a perfect fifth (just intonation) does not quite result in a return to the pitch class of the starting note after going around the circle of fifths. Twelve-tone equal temperament tuning produces fifths that return to a tone exactly seven octaves above the initial tone and makes the frequency ratio of the chromatic semitone the same as that of the diatonic semitone. The standard tempered fifth has a frequency ratio of 27/12:1 (or about 1.498307077:1), approximately two cents narrower than a justly tuned fifth.

Ascending by twelve justly tuned fifths fails to close the circle by an excess of approximately 23.46 cents, roughly a quarter of a semitone, an interval known as the Pythagorean comma. If limited to twelve pitches per octave, Pythagorean tuning markedly shortens the width of one of the twelve fifths, which makes it severely dissonant. This anomalous fifth is called the wolf fifth – a humorous reference to a wolf howling an off-pitch note. Non-extended quarter-comma meantone uses eleven fifths slightly narrower than the equally tempered fifth, and requires a much wider and even more dissonant wolf fifth to close the circle. More complex tuning systems based on just intonation, such as 5-limit tuning, use at most eight justly tuned fifths and at least three non-just fifths (some slightly narrower, and some slightly wider than the just fifth) to close the circle.

Equal-tempered tunings with more than twelve notes[edit]

Nowadays, with the advent of electronic isomorphic keyboards, equal temperament tunings with more than twelve notes per octave can be used to close the circle of fifths for other tunings. For example, 31-tone equal temperament closely approximates quarter-comma meantone, and 53-tone equal temperament closely approximates Pythagorean tuning.

History[edit]

The circle of fifths developed in the late 1600s and early 1700s to theorize the modulation of the Baroque era (see § Baroque era).

The first circle of fifths diagram appears in the Grammatika (1677) of the composer and theorist Nikolay Diletsky, who intended to present music theory as a tool for composition.[7] It was "the first of its kind, aimed at teaching a Russian audience how to write Western-style polyphonic compositions."

A circle of fifths diagram was independently created by German composer and theorist Johann David Heinichen in his Neu erfundene und gründliche Anweisung (1711),[8] which he called the "Musical Circle" (German: Musicalischer Circul).[9][10] This was also published in his Der General-Bass in der Composition (1728).

Heinichen placed the relative minor key next to the major key, which did not reflect the actual proximity of keys. Johann Mattheson (1735) and others attempted to improve this—David Kellner (1737) proposed having the major keys on one circle, and the relative minor keys on a second, inner circle. This was later developed into chordal space, incorporating the parallel minor as well.[11]

Some sources imply that the circle of fifths was known in antiquity, by Pythagoras.[12][13][14] This is a misunderstanding and an anachronism.[15] Tuning by fifths (so-called Pythagorean tuning) dates to Ancient Mesopotamia;[16] see Music of Mesopotamia § Music theory, though they did not extend this to a twelve note scale, stopping at seven. The Pythagorean comma was calculated by Euclid and by Chinese mathematicians (in the Huainanzi); see Pythagorean comma § History. Thus, it was known in antiquity that a cycle of twelve fifths was almost exactly seven octaves (more practically, alternating ascending fifths and descending fourths was almost exactly an octave). However, this was theoretical knowledge, and was not used to construct a repeating twelve-tone scale, nor to modulate. This was done later in meantone temperament and twelve-tone equal temperament, which allowed modulation while still being in tune, but did not develop in Europe until about 1500. Although popularized as the circle of fifths, its Anglo-Saxon etymological origins trace back to the name "wheel of fifths."

Use[edit]

In musical pieces from the Baroque music era and the Classical era of music and in Western popular music, traditional music and folk music, when pieces or songs modulate to a new key, these modulations are often associated with the circle of fifths.

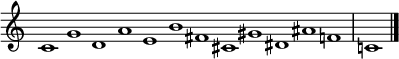

In practice, compositions rarely make use of the entire circle of fifths. More commonly, composers make use of "the compositional idea of the 'cycle' of 5ths, when music moves consistently through a smaller or larger segment of the tonal structural resources which the circle abstractly represents."[17] The usual practice is to derive the circle of fifths progression from the seven tones of the diatonic scale, rather from the full range of twelve tones present in the chromatic scale. In this diatonic version of the circle, one of the fifths is not a true fifth: it is a tritone (or a diminished fifth), e.g. between F and B in the "natural" diatonic scale (i.e. without sharps or flats). Here is how the circle of fifths derives, through permutation from the diatonic major scale:

And from the (natural) minor scale:

The following is the basic sequence of chords that can be built over the major bass-line:

And over the minor:

Adding sevenths to the chords creates a greater sense of forward momentum to the harmony:

Baroque era[edit]

According to Richard Taruskin, Arcangelo Corelli was the most influential composer to establish the pattern as a standard harmonic "trope": "It was precisely in Corelli's time, the late seventeenth century, that the circle of fifths was being 'theorized' as the main propellor of harmonic motion, and it was Corelli more than any one composer who put that new idea into telling practice."[18]

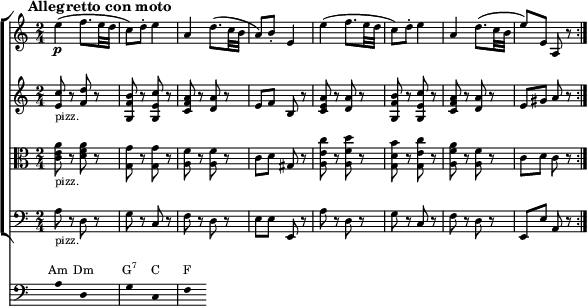

The circle of fifths progression occurs frequently in the music of J. S. Bach. In the following, from Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, BWV 51, even when the solo bass line implies rather than states the chords involved:

Handel uses a circle of fifths progression as the basis for the Passacaglia movement from his Harpsichord suite No. 6 in G minor.

Baroque composers learnt to enhance the "propulsive force" of the harmony engendered by the circle of fifths "by adding sevenths to most of the constituent chords." "These sevenths, being dissonances, create the need for resolution, thus turning each progression of the circle into a simultaneous reliever and re-stimulator of harmonic tension... Hence harnessed for expressive purposes."[19] Striking passages that illustrate the use of sevenths occur in the aria "Pena tiranna" in Handel's 1715 opera Amadigi di Gaula:

– and in Bach's keyboard arrangement of Alessandro Marcello's Concerto for Oboe and Strings.

Nineteenth century[edit]

Franz Schubert's Impromptu in E-flat major, D 899, contains harmonies that move in a modified circle of fifths:

The Intermezzo movement from Mendelssohn's String Quartet No.2 has a short segment with circle-of-fifths motion (the ii° is substituted by iv):

Robert Schumann's "Child falling asleep" from his Kinderszenen uses the progression, changing it at the end—the piece ends on an A minor chord, instead of the expected tonic E minor.

In Wagner's opera, Götterdämmerung, a cycle of fifths progression occurs in the music which transitions from the end of the prologue into the first scene of Act 1, set in the imposing hall of the wealthy Gibichungs. "Status and reputation are written all over the motifs assigned to Gunther",[20] chief of the Gibichung clan:

Jazz and popular music[edit]

The enduring popularity of the circle of fifths as both a form-building device and as an expressive musical trope is evident in the number of "standard" popular songs composed during the twentieth century. It is also favored as a vehicle for improvisation by jazz musicians, as the circle of fifths helps songwriters understand intervals, chord-relationships and progressions.

The song opens with a pattern of descending phrases – in essence, the hook of the song – presented with a soothing predictability, almost as if the future direction of the melody is dictated by the opening five notes. The harmonic progression, for its part, rarely departs from the circle of fifths.[21]

- Jerome Kern, "All the Things You Are"[22]

- Ray Noble, "Cherokee." Many jazz musicians have found this particularly challenging as the middle eight progresses so rapidly through the circle, "creating a series of II–V–I progressions that temporarily pass through several tonalities."[23]

- Kosma, Prévert and Mercer, "Autumn Leaves"[24]

- The Beatles, "You Never Give Me Your Money"[25][non-primary source needed]

- Mike Oldfield, "Incantations"[26]

- Carlos Santana, "Europa (Earth's Cry Heaven's Smile)"[citation needed]

- Gloria Gaynor, "I Will Survive"[27][non-primary source needed]

- Pet Shop Boys, "It's a Sin"[28][non-primary source needed]

- Donna Summer, "Love to Love you, Baby"[29][non-primary source needed]

Related concepts[edit]

Diatonic circle of fifths[edit]

The diatonic circle of fifths is the circle of fifths encompassing only members of the diatonic scale. Therefore, it contains a diminished fifth, in C major between B and F. See structure implies multiplicity. The circle progression is commonly a circle of fifths through the diatonic chords, including one diminished chord. A circle progression in C major with chords I–IV–viio–iii–vi–ii–V–I is shown below.

Chromatic circle[edit]

The circle of fifths is closely related to the chromatic circle, which also arranges the equal-tempered pitch classes of a particular tuning in a circular ordering. A key difference between the two circles is that the chromatic circle can be understood as a continuous space where every point on the circle corresponds to a conceivable pitch class, and every conceivable pitch class corresponds to a point on the circle. By contrast, the circle of fifths is fundamentally a discrete structure arranged through distinct intervals, and there is no obvious way to assign pitch classes to each of its points. In this sense, the two circles are mathematically quite different.

However, for any positive integer N, the pitch classes in N-tone equal temperament can be represented by the cyclic group of order N, or equivalently, the residue classes modulo equal to N, . In twelve-tone equal temperament, the group has four generators, which can be identified with the ascending and descending semitones and the ascending and descending perfect fifths. The semitonal generator gives rise to the chromatic circle while the perfect fourth and perfect fifth give rise to the circle of fifths. In most other tunings, such as in 31 equal temperament, many more intervals can be used as the generator, and many more circles are possible as a result.

Relation with chromatic scale[edit]

The circle of fifths, or fourths, may be mapped from the chromatic scale by multiplication, and vice versa. To map between the circle of fifths and the chromatic scale (in integer notation) multiply by 7 (M7), and for the circle of fourths multiply by 5 (P5).

In twelve-tone equal temperament, one can start off with an ordered 12-tuple (tone row) of integers:

- (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11)

representing the notes of the chromatic scale: 0 = C, 2 = D, 4 = E, 5 = F, 7 = G, 9 = A, 11 = B, 1 = C♯, 3 = D♯, 6 = F♯, 8 = G♯, 10 = A♯. Now multiply the entire 12-tuple by 7:

- (0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, 56, 63, 70, 77)

and then apply a modulo 12 reduction to each of the numbers (subtract 12 from each number as many times as necessary until the number becomes smaller than 12):

- (0, 7, 2, 9, 4, 11, 6, 1, 8, 3, 10, 5)

which is equivalent to

- (C, G, D, A, E, B, F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, F)

which is the circle of fifths. This is enharmonically equivalent to:

- (C, G, D, A, E, B, G♭, D♭, A♭, E♭, B♭, F).

Enharmonic equivalents, theoretical keys, and the spiral of fifths[edit]

Equal temperament tunings do not use the exact 3:2 ratio of frequencies that defines a perfect fifth, whereas just intonation uses this exact ratio. Ascending by fifths in equal temperament leads to a return to the starting pitch class—starting with a C and ascending by fifths leads to another C after a certain number of iterations. This does not occur if an exact 3:2 ratio is used (just intonation). The adjustment made in equal temperament tuning is called the Pythagorean comma. Because of this difference, pitches that are enharmonically equivalent in equal temperaments (such as C♯ and D♭ in 12-tone equal temperament, or C♯ and D![]() in 19 equal temperament) are not equivalent when using just intonation.

in 19 equal temperament) are not equivalent when using just intonation.

In just intonation the sequence of fifths can therefore be visualized as a spiral, not a circle—a sequence of twelve fifths results in a "comma pump" by the Pythagorean comma, visualized as going up a level in the spiral. See also § Circle closure in non-equal tuning systems.

Without enharmonic equivalences, continuing a sequence of fifths results in notes with double accidentals (double sharps or double flats), or even triple or quadruple accidentals. In most equal temperament tunings, these can be replaced by enharmonically equivalent notes.

Keys with double or triple sharps and flats in key signatures are called theoretical keys; they are redundant in 12-tone equal temperament, and so their use is extremely rare, but if the number of notes per octave is not a multiple of 12, they are distinguished. Notation in these cases is not standardized.

The default behaviour of LilyPond (pictured above) writes single sharps or flats in the circle-of-fifths order, before proceeding to double sharps or flats. This is the format used in John Foulds' A World Requiem, Op. 60,[31] which ends with the key signature of G♯ major, as displayed above. The sharps in the key signature of G♯ major here proceed C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, F![]() .

.

Single sharps or flats in the key signature are sometimes repeated as a courtesy, e.g. Max Reger's Supplement to the Theory of Modulation, which contains D♭ minor key signatures on pp. 42–45. These have a B♭ at the start and also a B![]() at the end (with a double-flat symbol), going B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B

at the end (with a double-flat symbol), going B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B![]() . The convention of LilyPond and Foulds would suppress the initial B♭.

Sometimes the double signs are written at the beginning of the key signature, followed by the single signs. For example, the F♭ key signature is notated as B

. The convention of LilyPond and Foulds would suppress the initial B♭.

Sometimes the double signs are written at the beginning of the key signature, followed by the single signs. For example, the F♭ key signature is notated as B![]() , E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭. This convention is used by Victor Ewald,[32] by the program Finale, and by some theoretical works.

, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭. This convention is used by Victor Ewald,[32] by the program Finale, and by some theoretical works.

See also[edit]

- Approach chord

- Sonata form

- Well temperament

- Circle of fifths text table

- Pitch constellation

- Multiplicative group of integers modulo n

- Multiplication (music)

- Circle of thirds

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Michael Pilhofer and Holly Day (23 Feb 2009). "The Circle of Fifths: A Brief History", www.dummies.com.

- ^ Broekhuis, Rogier (2022-10-11). "Wheel of Fifths – Harmonic Function". Wheel of Fifths. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ^ Nattiez 1990, p. 225.

- ^ Goldman 1965, p. 68.

- ^ Goldman 1965, chapter 3.

- ^ Nattiez 1990, p. 226.

- ^ Jensen 1992, pp. 306–307

- ^ Johann David Heinichen, Neu erfundene und gründliche Anweisung (1711), p. 261

- ^ Barnett 2002, p. 444.

- ^ Lester 1989, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Lerdahl, Fred (2005). Tonal Pitch Space. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 0195178297.

- ^ "The Circle of Fifths Complete Guide!". 17 January 2021.

- ^ "The Circle of Fifths made clear".

- ^ "Dummies - Learning Made Easy".

- ^ Fraser, Peter A. (2001), The Development of Musical Tuning Systems (PDF), pp. 9, 13, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2013, retrieved 24 May 2020

- ^ Dumbrill, Richard J. (2005). The archaeomusicology of the Ancient Near East. Victoria, B.C. p. 18. ISBN 978-1412055383.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Whittall, A. (2002, p. 259) "Circle of Fifths", article in Latham, E. (ed.) The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Taruskin 2010, p. 184.

- ^ Taruskin 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Scruton, R. (2016, p. 121) The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung. London, Allen Lane.

- ^ Gioia 2012, p. 115.

- ^ Gioia 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Scott, Richard J. (2003, p. 123) Chord Progressions for Songwriters. Bloomington Indiana, Writers Club Press.

- ^ Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy; Almén, Byron (2013). Tonal Harmony with an Introduction to Twentieth-century Music (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 46, 238. ISBN 978-0-07-131828-0.

- ^ "You Never Give Me Your Money" (1989, pp. 1099–1100, bars 1–16) The Beatles Complete Scores. Hal Leonard.

- ^ Oakes, Tim (June 1980). "Mike Oldfield". International Musician and Recording World. Retrieved 19 February 2021 – via Tubular.net.

- ^ Fekaris, D. and Perren, F. J. (1978) "I Will Survive". Polygram International Publishing.

- ^ Tennant, N. and Lowe, C. (1987, bars 1–8) "It's a Sin." Sony/ATV Music Publishing (UK) Ltd.

- ^ Moroder, G., Bellote, P. and Summer, D. (1975, bars 11–14) "Love to Love you, Baby" 1976, Bulle Music

- ^ McCartin 1998, p. 364.

- ^ "Foulds, John, A World Requiem, Op. 60, pp. 153ff".

- ^ "Ewald, Victor, Quintet No 4 in A♭, Op. 8 for Brass Quintet [211.01]".

Sources[edit]

- Barnett, Gregory (2002). "Tonal Organization in Seventeenth-century Music Theory.". In Thomas Christensen (ed.). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 407–455.

- Gioia, Ted (2012). The Jazz Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199769155.

- Goldman, Richard Franko (1965). Harmony in Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Jensen, Claudia R. (Summer 1992). "A Theoretical Work of Late Seventeenth-Century Muscovy: Nikolai Diletskii's "Grammatika" and the Earliest Circle of Fifths". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 45 (2): 305–331. doi:10.2307/831450. JSTOR 831450.

- Lester, Joel (1989). Between Modes and Keys: German theory 1592–1802. Stuyvesant: Pendragon Press.

- McCartin, Brian J. (November 1998). "Prelude to Musical Geometry". The College Mathematics Journal. 29 (5): 354–370. doi:10.1080/07468342.1998.11973971. JSTOR 2687250. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music, translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02714-5. (Originally published in French, as Musicologie générale et sémiologie. Paris: C. Bourgois, 1987. ISBN 2-267-00500-X).

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press.

Further reading[edit]

- D'Indy, Vincent (1903). Cours de composition musicale. Paris: A. Durand et fils.

- Lester, Joel. Between Modes and Keys: German Theory, 1592–1802. 1990.

- Miller, Michael. The Complete Idiot's Guide to Music Theory, 2nd ed. [Indianapolis, IN]: Alpha, 2005. ISBN 1-59257-437-8.

- Purwins, Hendrik (2005)."Profiles of Pitch Classes: Circularity of Relative Pitch and Key—Experiments, Models, Computational Music Analysis, and Perspectives". Ph.D. thesis. Berlin: Technische Universität Berlin.

- Purwins, Hendrik, Benjamin Blankertz, and Klaus Obermayer (2007). "Toroidal Models in Tonal Theory and Pitch-Class Analysis". in: Computing in Musicology 15 ("Tonal Theory for the Digital Age"): 73–98.

![{ <<

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff = "chords" << \magnifyStaff #2/3

\new Voice \relative c' {

\key f \major \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 40 \time 3/4

\mark \markup { \abs-fontsize #10 { \bold { Adagio } } }

d8 d d d d d | e e e e e e | g g g g g g | \stemUp d'( f) \stemNeutral f( a) a( c16 bes) | bes2 \mordent r4 | \break

c,8( e16 d) e8( g16 f) g8( bes16 a) | a2 \mordent r4 | bes,16( c32 a bes16 d32 cis) d16( e32 cis d16 f32 e) f16( g32 e f16 a32 g) | \break

g2 \mordent r4 | a,32( gis a b a b cis b) cis( d cis d e d e f e f g! f g f g e) | f4 \mordent s4

}

\new Voice \relative c' {

s2. | s | \stemDown e8 e e e e e | f8

}

\new Staff << \magnifyStaff #2/3

\new Voice \relative c' {

\key f \major \clef F \time 3/4

R2. | d8 d d d d d | \stemUp cis cis cis cis cis cis | d <d f>[ <d f> <d f> <d f> <d f>] | <d f> <d f> <d f> <d f> <d f> <d f> | e e e e e e | <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> | d d d d d d | <bes d> <bes d> <bes d> <bes d> <bes d> <bes d> | cis cis cis cis cis cis | d[ d] s4

}

\new Voice \relative c' { \clef F

s2. | s | \stemDown a8 a a a a a | d, r r4 r | g8 g g g g g | c8 c c c c c | f, f f f f f | bes bes bes bes bes bes | e, e e e e e | a a a a a a | d,[ d] s4

}

\addlyrics \with { alignAboveContext = "chords" } { \override LyricText.font-size = #-1.5 _ _ _ _ _ _ Dm \markup{\concat{Gm\super{7}}} _ _ _ _ _ C _ _ _ _ _ \markup{\concat{F\super{maj7}}} _ _ _ _ _ B♭ _ _ _ _ _ \markup{\concat{Em\super{7(♭5)}}} _ _ _ _ _ \markup{\concat{A\super{7}}} _ _ _ _ _ Dm }

>> >> >>

\new Staff \with {

\omit TimeSignature

\magnifyStaff #2/3

firstClef = ##f

} \relative c'

{ \hide Staff.KeySignature \key f \major \clef bass

{\stopStaff s2. s s \startStaff \hide Stem d8 s s s s s g, s s s s s c s s s s s f, s s s s s bes s s s s s e, s s s s s a s s s s s d,}}

>> }

\layout { line-width = #150 }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/r/2rj0hc4pt0k6grm4sbdi8k7nqi1sdl7/2rj0hc4p.png)

![{<<

\new ChoirStaff <<

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 60 \time 3/4 \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"trumpet" \transposition f'^"in F"

\p \grace {s16 s} ees2( d4) | ees2( d4) | cis2. ~ cis4 r r | R2. | R | R | R | R | R

}

\new Staff \with{ \magnifyStaff #3/4 } <<

\new Voice \relative c' { \override Hairpin.minimum-length = #3

\set Staff.midiInstrument = #"trumpet" \transposition e'^"in E"

\p \grace {s16 s} \hide \pp <g bes>2( <bes g>4) | <g bes>2( <bes g>4) | <bes d>4.( <g bes>8 <a c>4 | <bes d>2.) |<bes d>4.( <g bes>8 <a c>4 ) | <bes d>2 ees4-! | c2._"(marc.)" | s2. | R | R

}

\new Voice \relative c' { \stemDown

\hide \p \grace {s16 s} s2. | s | s | s | s | s2 ees4-! | c2. | d4-! bes2 | R2. | R2. \bar "|."

} >> >>

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"trombone" \transposition e^"in E"

\p \grace {s16 s} \hide \pp g'2. ~ g ~ g ~ g | g ~ g2 bes4-! | g2._"(marc.)" | d'4-! bes2 | c2_"dim." r4 | \pp d2 r4

}

\new ChoirStaff <<

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \clef tenor \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"trombone"

\p \grace {s16 s} aes2( g4) | aes2( g4) | fis2. ~ fis | fis ~ fis2 b4-! | g2._"(marc.)" | cis4-! b2 | b2_"dim." r4 | \pp ais2 r4

}

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \clef F \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"trombone"

\p \grace {s16 s} \hide \pp <b, d>2. | <b d> | <b d> ~ <b d> | <b d> ~ <b d>2 <b g'>4-! | <e g>2._"(marc.)" | <fis a>4-! <d fis>2 | <e g>_"dim." r4 | \pp <cis fis>2 r4

} >>

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \clef F \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"trombone"

\p \grace {s16 s} \hide \pp f,,!2( g4) | f!2( g4) | gis2. ~ gis | g! ~ g2 e4 ~ e a8._"(marc.)"[ g16 fis8. e16] | d2 g4( | cis,2_"dim.") r4 | \pp fis2 r4

}

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \clef F \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"timpani"

\p \grace {b,16 b} b4 r r | \grace {b16 b} b4 r r | \grace {b16 b} b4 r r | r b b | \grace {b16 b} b4 r r | r b f' | b, r r | R2. | R | R

}

\relative c' {

\magnifyStaff #3/4 \clef F \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"tuba"

\p \grace {s16 s} R2. | R | R | R | R | r4 r e,, ~ e a8._"(marc.)"[ g16 fis8. e16] | d2 g4( cis,2_"dim." ) r4 | \pp fis2 r4

}

>> }

\layout { line-width = #150 }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/9/b9cg7s9gxq732qwfg97n25bgulyaxon/b9cg7s9g.png)