History of Africa

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Archaic humans emerged out of Africa between 0.5 and 1.8 million years ago. This was followed by the emergence of modern humans (Homo sapiens) in East Africa around 300,000–250,000 years ago. In the 4th millenium BC written history arose in Ancient Egypt,[1] and later in Nubia’s Kush, the Horn of Africa’s Dʿmt, and the Maghreb and Ifrikiya’s Carthage.[2] Sub-Saharan societies are generally termed oral rather than literate civilisations, owing to their use of oral tradition even when a writing system has historically been accessed or developed; the tradition of the Ghana Empire is thought to contain content from prehistory. Between around 1000 BC and 1000 AD, the Bantu expansion swept from north-western Central Africa (modern day Cameroon) across much of sub-Saharan Africa in waves, laying the foundations for future states in Central, Eastern, and Southern regions of the continent.[3]

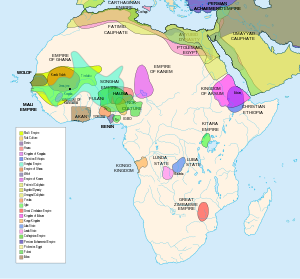

Africa was home to many kingdoms and empires in all regions of the continent, with historical change commonplace. Many states were created through conquest and insecurity, while others developed through the borrowing and assimilation of ideas and institutions, and some through internal, largely isolated development, stimulated by population growth and economic development.[4] Many societies maintained an egalitarian way of life, such as the Jola or Hadza peoples, while others did not centralise further into complex societies, such as the Boorana and the chiefdoms of Sierra Leone, and are rarely discussed in political history. At its peak it is estimated that Africa had up to 10,000 different states and autonomous groups having distinct languages and customs, with most following African traditional religions.[5]

Many empires achieved hegemony in their respective regions, such as Ghana, Mali, Songhai, and Sokoto in West Africa; Ancient Egypt, Kush, Carthage, the Fatimids, Almoravids, Almohads, Ayyubids, and Mamluks in North Africa; Aksum, Ethiopia, Adal, Kitara, Kilwa, and Imerina in East Africa; Kanem-Bornu, Kongo, Luba, and Lunda in Central Africa; and Mapungubwe, Zimbabwe, Mutapa, Rozvi, Maravi, Mthwakazi, and Zulu in Southern Africa. In sub-Saharan African societies, history was generally recorded orally, serving a different function to the academic discipline of history, with the diversity of languages and narratives, and academic scepticism making general histories of Africa rare. Academic disciplines such as the study of oral traditions, historical linguistics, archaeology, and genetics have been vital in compiling written histories of Africa.[6]

From the 7th century AD, Islam spread west from Arabia via conquest and proselytisation to North Africa and the Horn of Africa, and later southwards to the Swahili coast assisted by Muslim dominance of the Indian Ocean trade, then from the Maghreb traversing the Sahara into the western Sahel and Sudan, catalysed by the Fulani Jihad in the 18th and 19th centuries. Systems of servitude and slavery were historically widespread and commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the ancient, medieval, and early modern world.[7] When the trans-Saharan, Red Sea, Indian Ocean and Atlantic slave trades began, many of the pre-existing local slave systems started supplying captives for slave markets outside Africa.[8][9] The Atlantic slave trade was narrowly the most exploited of these, and over a shorter period between 1450 and 1900 transported upwards of 12 million enslaved people overseas.[10][11]

From 1870 to 1914, driven by the great force and voracity of the Second Industrial Revolution, European colonisation of Africa developed rapidly from one-tenth of the continent being under European imperial control to over nine-tenths in the Scramble for Africa, with the major European powers partitioning the continent in the 1884 Berlin Conference.[12][13] European rule had significant impacts on Africa's societies and the suppression of communal autonomy disrupted local customary practices and caused the irreversible transformation of Africa's socioeconomic systems.[14] While Christianity has a long history in north and east Africa, there were few Christian states preceding the colonial period, other than Ethiopia and Kongo. Widespread conversion occurred in southern West Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa under European rule due to efficacious missions, with peoples merging Christianity with their local beliefs.[15]

Following struggles for independence in many parts of the continent, and a weakened Europe after the Second World War, waves of decolonisation took place across the continent. This culminated in the 1960 Year of Africa and the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963 (the predecessor to the African Union), with countries deciding to keep their colonial borders.[16] Traditional power structures remain partly in place in many parts of Africa, and their roles, powers, and influence vary greatly between countries, especially regarding governance.

Prehistory

[edit]

The first known hominids evolved in Africa. According to paleontology, the early hominids' skull anatomy was similar to that of the gorilla and the chimpanzee, great apes that also evolved in Africa, but the hominids had adopted a bipedal locomotion which freed their hands. This gave them a crucial advantage, enabling them to live in both forested areas and on the open savanna at a time when Africa was drying up and the savanna was encroaching on forested areas. This would have occurred 10 to 5 million years ago, but these claims are controversial because biologists and genetics have humans appearing around the last 70 thousand to 200 thousand years.[17]

The fossil record shows Homo sapiens (also known as "modern humans" or "anatomically modern humans") living in Africa by about 350,000–260,000 years ago. The earliest known Homo sapiens fossils include the Jebel Irhoud remains from Morocco (c. 315,000 years ago),[18] the Florisbad Skull from South Africa (c. 259,000 years ago), and the Omo remains from Ethiopia (c. 233,000 years ago).[19][20][21][22][23] Scientists have suggested that Homo sapiens may have arisen between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago through a merging of populations in East Africa and South Africa.[24][25]

Evidence of a variety of behaviors indicative of Behavioral modernity date to the African Middle Stone Age, associated with early Homo sapiens and their emergence. Abstract imagery, widened subsistence strategies, and other "modern" behaviors have been discovered from that period in Africa, especially South, North, and East Africa.

The Blombos Cave site in South Africa, for example, is famous for rectangular slabs of ochre engraved with geometric designs. Using multiple dating techniques, the site was confirmed to be around 77,000 and 100–75,000 years old.[26][27] Ostrich egg shell containers engraved with geometric designs dating to 60,000 years ago were found at Diepkloof, South Africa.[28] Beads and other personal ornamentation have been found from Morocco which might be as much as 130,000 years old; as well, the Cave of Hearths in South Africa has yielded a number of beads dating from significantly prior to 50,000 years ago,[29] and shell beads dating to about 75,000 years ago have been found at Blombos Cave, South Africa.[30][31][32]

Around 65–50,000 years ago, the species' expansion out of Africa launched the colonization of the planet by modern human beings.[33][34][35][36] By 10,000 BC, Homo sapiens had spread to most corners of Afro-Eurasia. Their dispersals are traced by linguistic, cultural and genetic evidence.[37][38][39] Eurasian back-migrations, specifically West-Eurasian backflow, started in the early Holocene or already earlier in the Paleolithic period, sometimes between 30 and 15,000 years ago, followed by pre-Neolithic and Neolithic migration waves from the Middle East, mostly affecting Northern Africa, the Horn of Africa, and wider regions of the Sahel zone and East Africa.[40]

Affad 23 is an archaeological site located in the Affad region of southern Dongola Reach in northern Sudan,[41] which hosts "the well-preserved remains of prehistoric camps (relics of the oldest open-air hut in the world) and diverse hunting and gathering loci some 50,000 years old".[42][43][44]

Around 16,000 BC, from the Red Sea Hills to the northern Ethiopian Highlands, nuts, grasses and tubers were being collected for food. By 13,000 to 11,000 BC, people began collecting wild grains. This spread to Western Asia, which domesticated its wild grains, wheat and barley. Between 10,000 and 8000 BC, Northeast Africa was cultivating wheat and barley and raising sheep and cattle from Southwest Asia.

A wet climatic phase in Africa turned the Ethiopian Highlands into a mountain forest. Omotic speakers domesticated enset around 6500–5500 BC. Around 7000 BC, the settlers of the Ethiopian highlands domesticated donkeys, and by 4000 BC domesticated donkeys had spread to Southwest Asia. Cushitic speakers, partially turning away from cattle herding, domesticated teff and finger millet between 5500 and 3500 BC.[45]

During the 11th millennium BP, pottery was independently invented in Africa, with the earliest pottery there dating to about 9,400 BC from central Mali.[46] It soon spread throughout the southern Sahara and Sahel.[47] In the steppes and savannahs of the Sahara and Sahel in Northern West Africa, the Nilo-Saharan speakers and Mandé peoples started to collect and domesticate wild millet, African rice and sorghum between 8000 and 6000 BC. Later, gourds, watermelons, castor beans, and cotton were also collected and domesticated. The people started capturing wild cattle and holding them in circular thorn hedges, resulting in domestication.[48]

They also started making pottery and built stone settlements (e.g., Tichitt, Oualata). Fishing, using bone-tipped harpoons, became a major activity in the numerous streams and lakes formed from the increased rains.[49] Mande peoples have been credited with the independent development of agriculture about 4000–3000 BC.[50]

Evidence of the early smelting of metals – lead, copper, and bronze – dates from the fourth millennium BC.[51]

Egyptians smelted copper during the predynastic period, and bronze came into use after 3,000 BC at the latest[52] in Egypt and Nubia. Nubia became a major source of copper as well as of gold.[53] The use of gold and silver in Egypt dates back to the predynastic period.[54][55]

In the Aïr Mountains of present-day Niger people smelted copper independently of developments in the Nile valley between 3,000 and 2,500 BC. They used a process unique to the region, suggesting that the technology was not brought in from outside; it became more mature by about 1,500 BC.[55]

By the 1st millennium BC iron working had reached Northwestern Africa, Egypt, and Nubia.[56] Zangato and Holl document evidence of iron-smelting in the Central African Republic and Cameroon that may date back to 3,000 to 2,500 BC.[57] Assyrians using iron weapons pushed Nubians out of Egypt in 670 BC, after which the use of iron became widespread in the Nile valley.[58]

The theory that iron spread to Sub-Saharan Africa via the Nubian city of Meroe[59] is no longer widely accepted, and some researchers believe that sub-Saharan Africans invented iron metallurgy independently. Metalworking in West Africa has been dated as early as 2,500 BC at Egaro west of the Termit in Niger, and iron working was practiced there by 1,500 BC.[60] Iron smelting has been dated to 2,000 BC in southeast Nigeria.[61] Central Africa provides possible evidence of iron working as early as the 3rd millennium BC.[62] Iron smelting developed in the area between Lake Chad and the African Great Lakes between 1,000 and 600 BC, and in West Africa around 2,000 BC, long before the technology reached Egypt. Before 500 BC, the Nok culture in the Jos Plateau was already smelting iron.[63][64][65][66][67][68] Archaeological sites containing iron-smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in Igboland: dating to 2,000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[61][69] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[69] The site of Gbabiri (in the Central African Republic) has also yielded evidence of iron metallurgy, from a reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop; with earliest dates of 896–773 BC and 907–796 BC respectively.[68]

4th millennium BC – 6th century AD

[edit]North-East Africa and the Horn of Africa

[edit]North-East Africa

[edit]

The ancient history of North Africa is inextricably linked to that of the Ancient Near East and Europe. This is particularly true of the various cultures and dynasties of Ancient Egypt and of Nubia. From around 3500 BC, a coalition of Horus-worshipping nomes in the western Nile Delta conquered the Andjety-worshipping nomes of the east to form Lower Egypt, whilst Set-worshipping nomes in the south coalesced to form Upper Egypt.[70]: 62–63 Egypt was first united when Narmer of Upper Egypt conquered Lower Egypt, giving rise to the 1st and 2nd dynasties of Egypt whose efforts presumably consisted of conquest and consolidation, with unification completed by the 3rd dynasty to form the Old Kingdom of Egypt in 2686 BC.[70]: 63 The Kingdom of Kerma emerged around this time to become the dominant force in Nubia, controlling an area as large as Egypt between the 1st and 4th cataracts of the Nile, with Egyptian records speaking of its rich and populous agricultural regions.[71][72] The height of the Old Kingdom came under the 4th dynasty who constructed numerous great pyramids, however under the 6th dynasty of Egypt power began to decentralise to the nomarchs, culminating in anarchy exacerbated by drought and famine in 2200 BC, and the onset of the First Intermediate Period in which numerous nomarchs ruled simultaneously. Throughout this time, power bases were built and destroyed in Memphis, and in Heracleopolis, when Mentuhotep II of Thebes and the 11th dynasty conquered all of Egypt to form the Middle Kingdom in 2055 BC. The 12th dynasty oversaw advancements in irrigation and economic expansion in the Faiyum Oasis, as well as expansion into Lower Nubia at the expense of Kerma. In 1700 BC, Egypt fractured in two, ushering in the Second Intermediate Period.[70]: 68–71

The Hyksos, a militaristic people from Palestine, capitalised on this fragmentation and conquered Lower Egypt, establishing the 15th dynasty of Egypt, whilst Kerma coordinated invasions deep into Egypt to reach its greatest extent, looting royal statues and monuments.[73] A rival power base developed in Thebes with Ahmose I of the 18th dynasty eventually expelling the Hyksos from Egypt, forming the New Kingdom in 1550 BC. Utilising the military technology the Hyksos had brought, they conducted numerous campaigns to conquer the Levant from the Canaanites, Amorites, Hittites, and Mitanni, and extinguish Kerma, incorporating Nubia into the empire, sending the Egyptian empire into its golden age.[70]: 73 Internal struggles, drought and famine, and invasions by a confederation of seafaring peoples, contributed to the New Kingdom's collapse in 1069 BC, ushering in the Third Intermediate Period which saw Egypt fractured into many pieces amid widespread turmoil.[70]: 76–77 Egypt's disintegration liberated the more Egyptianized Kingdom of Kush in Nubia, and later in the 8th century BC the Kushite king Kashta would expand his power and influence by manoeuvring his daughter into a position of power in Upper Egypt, paving the way for his successor Piye to conquer Lower Egypt and form the Kushite Empire. The Kushites assimilated further into Egyptian society by reaffirming Ancient Egyptian religious traditions, and culture, while introducing some unique aspects of Kushite culture and overseeing a revival in pyramid-building. After a century of rule they were forcibly driven out of Egypt by the Assyrians as reprisal for the Kushites agitating peoples within the Assyrian Empire in an attempt to gain a foothold in the region.[74] The Assyrians installed a puppet dynasty which later gained independence and once more unified Egypt, with Upper Egypt becoming a rich agricultural region whose produce Lower Egypt then sold and traded.[70]: 77

In 525 BC Egypt was conquered by the expansive Achaemenids, however later regained independence in 404 BC until 343 BC when it was re-annexed by the Achaemenid Empire. Persian rule in Egypt ended with the defeat of the Achaemenids by Alexander the Great in 332 BC, marking the beginning of Hellenistic rule by the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. The Hellenistic rulers, seeking legitimacy from their Egyptian subjects, gradually Egyptianized and participated in Egyptian religious life.[75]: 119 Following the Syrian Wars with the Seleucid Empire, the Ptolemaic Kingdom lost its holdings in outside Africa, but expanded its territory by conquering Cyrenaica from its respective tribes, and subjugated Kush. Beginning in the mid second century BC, dynastic strife and a series of foreign wars weakened the kingdom, and it became increasingly reliant on the Roman Republic. Under Cleopatra VII, who sought to restore Ptolemaic power, Egypt became entangled in a Roman civil war, which ultimately led to its conquest by Rome in 30 BC. The Crisis of the Third Century in the Roman Empire freed the Levantine city state of Palmyra who conquered Egypt, however their rule lasted only a few years before Egypt was reintegrated into the Roman Empire. In the midst of this, Kush regained total independence from Egypt, and they would persist as a major regional power until, having been weakened from internal rebellion amid worsening climatic conditions, invasions by both the Aksumites and the Noba caused their disintegration into Makuria, Alodia, and Nobatia in the 5th century AD, whilst the Romans managed to hold on to Egypt for the rest of the ancient period.

Horn of Africa

[edit]

In the Horn of Africa there was the Land of Punt, a kingdom on the Red Sea, likely located in modern-day Eritrea or northern Somaliland.[76] The Ancient Egyptians initially traded via middle-men with Punt until in 2350 BC when they established direct relations. They would become close trading partners for over a millennium, with Punt exchanging gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory and wild animals. Towards the end of the ancient period, northern Ethiopia and Eritrea bore the Kingdom of D'mt beginning in 980 BC, whose people developed irrigation schemes, used ploughs, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons. In modern-day Somalia and Djibouti there was the Macrobian Kingdom, with archaeological discoveries indicating the possibility of other unknown sophisticated civilisations at this time.[77][78] After D'mt's fall in the 5th century BC the Ethiopian Plateau came to be ruled by numerous smaller unknown kingdoms who experienced strong south Arabian influence, until the growth and expansion of Aksum in the 1st century BC.[79] Along the Horn's coast there were many ancient Somali city-states which thrived off of the wider Red Sea trade and transported their cargo via beden, exporting myrrh, frankincense, spices, gum, incense, and ivory, with freedom from Roman interference causing Indians to give the cities a lucrative monopoly on cinnamon from ancient India.[80]

The Kingdom of Aksum grew from a principality into a major power on the trade route between Rome and India through conquering its unfortunately unknown neighbours, gaining a monopoly on Indian Ocean trade in the region. Aksum's rise had them rule over much of the regions from the Lake Tana to the valley of the Nile, and they further conquered parts of the ailing Kingdom of Kush, led campaigns against the Noba and Beja peoples, and expanded into South Arabia.[81][82][83] This led the Persian prophet Mani to consider Aksum as one of the four great powers of the 3rd century alongside Persia, Rome, and China.[84] In the 4th century AD Aksum's king converted to Christianity and Aksum's population, who had followed syncretic mixes of local beliefs, slowly followed. In the early 6th century AD, Cosmas Indicopleustes later described his visit to the city of Aksum, mentioning rows of throne monuments, some made out of "excellent white marble" and "entirely...hewn out of a single block of stone", with large inscriptions attributed to various kings, likely serving as victory monuments documenting the wars waged. The turn of the 6th century saw Aksum balanced against the Himyarite Kingdom in southwestern Arabia, as part of the wider Byzantine-Sassanian conflict. In 518, Aksum invaded Himyar against the persecution of the Christian community by Dhu Nuwas, the Jewish Himyarite king. Following the capture of Najran, the Aksumites implanted a puppet on the Himyarite throne, however a coup d'état in 522 brought Dhu Nuwas back to power who again began persecuting Christians. The Aksumites invaded again in 525, and with Byzantine aid conquered the kingdom, incorporating it as a vassal state after some minor internal conflict. In the late 6th century the Aksumites were driven out of Yemen by the Himyarite king with the aid of the Sassanids.

North-West Africa

[edit]

Further north-west, the Maghreb and Ifriqiya were mostly cut off from the cradle of civilisation in Egypt by the Libyan desert, exacerbated by Egyptian boats being tailored to the Nile and not coping well in the open Mediterranean Sea. This caused its societies to develop contiguous to those of Southern Europe, until Phoenician settlements came to dominate the most lucrative trading locations in the Gulf of Tunis, initially searching for sources of metal.[85]: 247 Phoenician settlements subsequently grew into Ancient Carthage after gaining independence from Phoenicia in the 6th century BC, and they would build an extensive empire, countering Greek influence in the Mediterranean, as well as a strict mercantile network reaching as far as west Asia and northern Europe, distributing an array of commodities from all over the ancient world along with locally produced goods, all secured by one of the largest and most powerful navies in the ancient Mediterranean. Carthage's political institutions received rare praise from both Greeks and Romans, with its constitution and aristocratic council providing stability, with birth and wealth paramount for election.[85]: 251–253 In 264 BC the First Punic War began when Carthage came into conflict with the expansionary Roman Republic on the island of Sicily, leading to what has been described as the greatest naval war of antiquity, causing heavy casualties on both sides, but ending in Carthage's eventual defeat and loss of Sicily.[85]: 255–256 The Second Punic War broke out when the Romans opportunistically took Sardinia and Corsica whilst the Carthaginians were putting down a ferocious Libyan revolt, with Carthage initially experiencing considerable success following Hannibal's infamous crossing of the alps into northern Italy. In a 14 year long campaign Hannibal's forces conquered much of mainland Italy, only being recalled after the Romans conducted a bold naval invasion of the Carthaginian homeland and then defeated him in climactic battle in 202 BC.[85]: 256–257

Carthage was forced to give up their fleet, and the subsequent collapse of their empire would produce two further polities in the Maghreb; Numidia, a polity made up of two Numidian tribal federations until the Massylii conquered the Masaesyli, and assisted the Romans in the Second Punic War; Mauretania, a Mauri tribal kingdom, home of the legendary King Atlas; and various tribes such as Garamantes, Musulamii, and Bavares. The Third Punic War would result in Carthage's total defeat in 146 BC and the Romans established the province of Africa, with Numidia assuming control of many of Carthage's African ports. Towards the end of the 2nd century BC Mauretania fought alongside Numidia's Jugurtha in the Jugurthine War against the Romans after he had usurped the Numidian throne from a Roman ally. Together they inflicted heavy casualties that quaked the Roman Senate, with the war only ending inconclusively when Mauretania's Bocchus I sold out the Jugurtha to the Romans.[85]: 258 At the turn of the millennium they both would face the same fate as Carthage and be conquered by the Romans who established Mauretania and Numidia as provinces of their empire, whilst Musulamii, led by Tacfarinas, and Garamantes were eventually defeated in war in the 1st century AD however weren't conquered.[86]: 261–262 In the 5th century AD the Vandals conquered north Africa precipitating the fall of Rome. Swathes of indigenous peoples would regain self-governance in the Mauro-Roman Kingdom and its numerous successor polities in the Maghreb, namely the kingdoms of Ouarsenis, Aurès, and Altava. The Vandals ruled Ifriqiya for a century until Byzantine reconquest in the early 6th century AD. The Byzantines and the Berber kingdoms fought minor inconsequential conflicts, such as in the case of Garmul, however largely coexisted.[86]: 284 Further inland to the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa were the Sanhaja in modern-day Algeria, a broad grouping of three groupings of tribal confederations, one of which is the Masmuda grouping in modern-day Morocco, along with the nomadic Zenata; their composite tribes would later go onto shape much of North African history.

West Africa

[edit]

In the western Sahel the rise of settled communities occurred largely as a result of the domestication of millet and of sorghum. Archaeology points to sizable urban populations in West Africa beginning in the 4th millennium BC, which had crucially developed iron metallurgy by 1200 BC, in both smelting and forging for tools and weapons.[87] Extensive east-west belts of deserts, grasslands, and forests from north to south were crucial in the moulding of their respective societies and meant that prior to the accession of trans-Saharan trade routes, symbiotic trade relations developed in response to the opportunities afforded by north–south diversity in ecosystems,[88] trading meats, copper, iron, salt, and gold. Various civilisations prospered in this period. From 4000 BC, the Tichitt culture in modern-day Mauritania and Mali was the oldest known complexly organised society in West Africa, with a four tiered hierarchical social structure.[89] Other civilisations include the Kintampo culture from 2500 BC in modern-day Ghana,[90] the Nok culture from 1500 BC in modern-day Nigeria,[91] the Daima culture around Lake Chad from 550 BC, Djenné-Djenno from 250 BC in modern-day Mali, and the Serer civilisation in modern-day Senegal which built the Senegambian stone circles from the 3rd century BC. There is also detailed record ([1]) of Igodomigodo, a small kingdom founded presumably in 40 BC which would later go on to form the Benin Empire.[92]

Towards the end of the 3rd century AD, a wet period in the Sahel created areas for human habitation and exploitation which had not been habitable for the best part of a millennium, with the Kingdom of Wagadu, the local name of the Ghana Empire, rising out of the Tichitt culture, growing wealthy following the introduction of the camel to the western Sahel, revolutionising the trans-Saharan trade which linked their capital and Aoudaghost with Tahert and Sijilmasa in North Africa.[93] Soninke traditions likely contain content from prehistory, mentioning multiple previous foundings of Wagadu, and holds that the final founding of Wagadu occurred after their first king killed Bida, a serpent deity, who was guarding a well, although accounts differ, with some stating he did a deal with Bida to sacrifice one maiden a year in exchange for assurance regarding plenty of rainfall and gold supply.[94] Wagadu's core traversed modern-day southern Mauritania and western Mali, and Soninke tradition portrays early Ghana as warlike, with horse-mounted warriors key to increasing its territory and population, although details of their expansion are extremely scarce.[93] Wagadu made its profits from maintaining a monopoly on gold heading north and salt heading south, relying on the Soninke Wangara due to not controlling the gold fields themselves, located in the forest regions.[95] It is probable that Wagadu's dominance on trade allowed for the gradual consolidation of many smaller polities into a confederated state, whose composites stood in varying relations to the core, from fully administered to nominal tribute-paying parity.[96] Based on large tumuli scattered across West Africa dating to this period, it has been stipulated that relative to Wagadu there were further simultaneous and preceding kingdoms which have unfortunately been lost to time.[97][89]

Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa

[edit]

1 = 2000–1500 BC origin

2 = c. 1500 BC first dispersal

2.a = Eastern Bantu

2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000–500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4–7 = southward advance

9 = 500–1 BC Congo nucleus

10 = AD 1–1000 last phase[98][99][100]

In Central Africa the Sao civilisation flourished for over a millennium beginning in the 6th century BC. The Sao lived by the Chari River south of Lake Chad in territory that later became part of present-day Cameroon and Chad. They are the earliest people to have left clear traces of their presence in the territory of northern Cameroon. Today several peoples, particularly the Sara, claim to have descended from the Sao. Sao artifacts show that they were skilled workers in bronze, copper, and iron,[101] with finds including bronze sculptures, terracotta statues of human and animal figures, coins, funerary urns, household utensils, jewellery, highly decorated pottery, and spears.[102] Nearby, around Lake Ejagham in south-west Cameroon, the Ekoi civilisation rose circa 2nd century AD, and are most notable for constructing the Ikom monoliths.

The Bantu expansion constituted a major series of migrations of Bantu peoples from central Africa to eastern and southern Africa and was substantial in the settling of the continent.[103] Commencing in the 2nd millennium BC, the Bantu began to migrate from Cameroon to the Congo Basin, laying the foundations for the cultures preceding the Kingdom of Kongo, and eastward to the Great Lakes region, forming the Urewe culture, which would lay the foundations for the Empire of Kitara, later producing the kingdoms of Buganda, Rwanda, and Burundi.[104][105] In the 7th century AD, Bantu spread to the Upemba Depression, forming the Upemba culture, which would later bear the Luba Empire and Lunda.[106] The Bantu then spread further from the Great Lakes to southern and east Africa over the 1st millennium BC. One early movement headed south to the upper Zambezi basin in the 2nd century BC. The Bantu then pushed westward to the savannahs of present-day Angola and eastward into Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe in the 1st century AD, forming the Gokomere culture in the 5th century AD, the predecessor to Leopard's Kopje, which would later evolve into the kingdoms of Mapungubwe and Zimbabwe.[107] The second thrust from the Great Lakes was eastward, also in the 1st century AD, expanding to Kenya, Tanzania, and the Swahili coast.

Prior to this migration, the northern part of the Swahili coast was home to the elusive Azania, most likely a Southern Cushitic polity, extending southwards to modern-day Tanzania.[108] The Bantu populations crowded out Azania, with Rhapta being its last stronghold by the 1st century AD,[109] and formed various city states constituting the Swahili civilisation, trading via the Indian Ocean trade.[110] Madagascar was possibly first settled by Austronesians from 350 BC-550 AD, termed the Vazimba in Malagasy oral traditions, although there is considerable academic debate.[111][112] The eastern Bantu group would eventually meet with the southern migrants from the Great Lakes in Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe and both groups continued southward, with eastern groups continuing to Mozambique and reaching Maputo in the 2nd century AD. Further to the south, settlements of Bantu peoples who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen were well established south of the Limpopo River by the 4th century AD, displacing and absorbing the original Khoisan. To their west in the Tsodilo hills of Botswana there were the San, a semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer people who are thought to have descended from the first inhabitants of Southern Africa 100,000 years BP, making them one of the oldest cultures on Earth.[113]

7th century–15th century

[edit]North Africa

[edit]Northern Africa

[edit]The turn of the 7th century saw much of North Africa controlled by the Byzantine Empire. Christianity was the state religion of the empire, and Semitic and Coptic subjects in Roman Egypt faced persecution due to their 'heretical' Miaphysite churches, paying a heavy tax. The Exarchate of Africa covered much of Ifriqiya and the eastern Maghreb, surrounded by numerous Berber kingdoms that followed Christianity heavily syncretised with traditional Berber religion. The interior was dominated by various groupings of tribal confederations, namely the nomadic Zenata, the Masmuda of Sanhaja in modern-day Morocco, and the other two Sanhaja in the Sahara in modern-day Algeria, who all mainly followed traditional Berber religion. In 618 the Sassanids conquered Egypt during the Byzantine-Sasanian War, however the province was reconquered three years later.

The early 7th century saw the inception of Islam and the beginning of the Arab conquests intent on converting peoples to Islam and monotheism.[114]: 56 The nascent Rashidun Caliphate won a series of crucial victories and expanded rapidly, forcing the Byzantines to evacuate Syria. With Byzantine regional presence shattered, Egypt was quickly conquered by 642, with the Egyptian Copts odious of Byzantine rule generally putting up little resistance. The Muslims' attention then turned west to the Maghreb where the Exarchate of Africa had declared independence from Constantinople under Gregory the Patrician. The Muslims conquered Ifriqiya and in 647 defeated and killed Gregory and his army decisively in battle. The Berbers of the Maghreb proposed payment of annual tribute, which the Muslims, not wishing to annex the territory, accepted. After a brief civil war in the Muslim empire, the Rashidun were supplanted by the Umayyad dynasty in 661 and the capital moved from Medina to Damascus. With intentions to expand further in all directions, the Muslims returned to the Maghreb to find the Byzantines had reinforced the Exarchate and allied with the Berber Kingdom of Altava under Kusaila, who was approached prior to battle and convinced to convert to Islam. Initially having become neutral, Kusaila objected to integration into the empire and in 683 destroyed the poorly supplied Arab army and conquered the newly-found Kairouan, causing an epiphany among the Berber that this conflict was not just against the Byzantines. The Arabs returned and defeated Kusaila and Altava in 690, and, after a set-back, expelled the Byzantines from North Africa. To the west, Kahina of the Kingdom of the Aurès declared opposition to the Arab invasion and repelled their armies, securing her position as the uncontested ruler of the Maghreb for five years. The Arabs received reinforcements and in 701 Kahina was killed and the kingdom defeated. They completed their conquest of the rest of the Maghreb, with large swathes of Berbers embracing Islam, and the combined Arab and Berber armies would use this territory as a springboard into Iberia to expand the Muslim empire further.[115]: 47–48

Large numbers of Berber and Coptic people willingly converted to Islam, and followers of Abrahamic religions (“People of the Book”) constituting the Dhimmi class were permitted to practice their religion and exempted from military service in exchange for a tax, which was improperly extended to include converts.[116]: 247 Followers of traditional Berber religion, which were mostly those of tribal confederations in the interior, were violently oppressed and often given the ultimatum to convert to Islam or face death or enslavement.[115]: 46 Converted natives were permitted to participate in the governing of the Muslim empire in order to quell the enormous administrative problems owing to the Arabs' lack of experience governing and rapid expansion.[115]: 49 Unorthodox sects such as the Kharijite, Ibadi, Isma'ili, Nukkarite and Sufrite found fertile soil among many Berbers dissatisfied with the oppressive Umayyad regime, with religion being utilised as a political tool to foster organisation.[114]: 64 In the 740s the Berber Revolt rocked the caliphate and the Berbers took control over the Maghreb, whilst revolts in Ifriqiya were suppressed. The Abbasid dynasty came to power via revolution in 750 and attempted to reconfigure the caliphate to be multi-ethnic rather than Arab exclusive, however this wasn't enough to prevent gradual disintegration on its peripheries. Various short-lived native dynasties would form states such as the Barghawata of Masmuda, the Ifranid dynasty, and the Midrarid dynasty, both hailing from the Zenata. The Idrisid dynasty would come to rule most of modern-day Morocco with the support of the Masmuda, whilst the growing Ibadi movement among the Zenata culminated in the Rustamid Imamate, an Ibadi theocracy centred on Tahert, modern-day Algeria.[116]: 254 At the turn of the 9th century the Abbasids' sphere of influence would degrade further with the Aghlabids controlling Ifriqiya under only nominal Abbasid rule and in 868 when the Tulunids wrestled the independence of Egypt for four decades before again coming under Abbasid control.[117]: 172, 260 Late in the 9th century, a revolt by East African slaves in the Abbasid's homeland of Iraq diverted its resources away from its other territories, devastating important ports in the Persian Gulf, and was eventually put down after decades of violence, resulting in between 300,000 and 2,500,000 dead.[118][119]: 714

This gradual bubbling of disintegration of the caliphate boiled over when the Fatimid dynasty rose out of the Bavares tribal confederation and in 909 conquered the Aghlabids to gain control over all of Ifriqiya. Proclaiming Isma'ilism, they established a caliphate rivalling the Abbasids, who followed Sunni Islam.[120]: 320 The nascent caliphate quickly conquered the ailing Rustamid Imamate and fought a proxy war against the remnants of the Umayyad dynasty centred in Cordoba, resulting the eastern Maghreb coming under the control of the vassalized Zirid dynasty, who hailed from the Sanhaja.[120]: 323 In 969 the Fatimids finally conquered Egypt against a weakened Abbasid Caliphate after decades of attempts, moving their capital to Cairo and deferring Ifriqiya to the Zirids. From there they conquered up to modern-day Syria and Hejaz, securing the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The Fatimids became absorbed by the eastern realms of their empire, and in 972, after encouragement from faqirs, the Zirids changed their allegiance to recognise the Abbasid Caliphate. In retaliation the Fatimids commissioned an invasion by nomadic Arab tribes to punish them, leading to their disintegration with the Khurasanid dynasty and Arab tribes ruling Ifriqiya, to be later displaced by the Norman Kingdom of Africa.[120]: 329 In the late 10th and early 11th centuries the Fatimids would lose the Maghreb to the Hammadids in modern-day Algeria and the Maghrawa in modern-day Morocco, both from Zenata. In 1053 the Saharan Sanhaja, spurred on by puritanical Sunni Islam, conquered Sijilmasa and captured Aoudaghost from the Ghana Empire to control the affluent trans-Saharan trade routes in the Western Sahara, forming the Almoravid empire before conquering Maghrawa and intervening in the reconquest of Iberia by the Christian powers on the side of the endangered Muslim taifas, which were produced from the fall of the remnant Umayyad Caliphate in Cordoba. The Almoravids incorporated the taifas into their empire, enjoying initial success, until a devastating ambush crippled their military leadership, and throughout the 12th century they gradually lost territory to the Christians.[121]: 351–354 To the east, the Fatimids saw their empire start to collapse in 1061, beginning with the loss of the holy cities to the Sharifate of Mecca and exacerbated by rebellion in Cairo. The Seljuk Turks, who saw themselves as the guardian of the Abbasid Caliphate, capitalised and conquered much of their territories in the east, however the Fatimids repelled them from encroaching on Egypt. Amid the Christians' First Crusade against the Seljuks, the Fatimids opportunistically took back Jerusalem, but then lost it again to the Christians in decisive defeat. The Fatimids' authority collapsed due to intense internal struggle in political rivalries and religious divisions, amid Christian invasions of Egypt, creating a power vacuum in North Africa. The Zengid dynasty, nominally under Seljuk suzerainty, invaded on the pretext of defending Egypt from the Christians, and usurped the position of vizier in the caliphate.[122]: 186–189

Following the assassination of the previous holder, the position of vizier passed onto Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub (commonly referred to as Saladin). After a joint Zengid-Fatimid effort repelled the Christians and after he had put down a revolt from the Fatimid army, Saladin eventually deposed the Fatimid caliph in 1171 and established the Ayyubid dynasty in its place, choosing to recognise the Abbasid Caliphate. From there the Ayyubids captured Cyrenaica, and went on a prolific campaign to conquer Arabia from the Zengids and the Yemeni Hamdanids, Palestine from the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem, and Syria and Upper Mesopotamia from other Seljuk successor states.[123]: 148–150 To the west, there was a new domestic threat to Almoravid rule; a religious movement headed by Ibn Tumart from the Masmuda tribal grouping, who was considered by his followers to be the true Mahdi. Initially fighting a guerilla war from the Atlas Mountains, they descended from the mountains in 1130 but were crushed in battle, with Ibn Tumart dying shortly after. The movement consolidated under the leadership of self-proclaimed caliph Abd al-Mu'min and, after gaining the support of the Zenata, swept through the Maghreb, conquering the Hammadids, the Hilalian Arab tribes, and the Norman Kingdom of Africa, before gradually conquering the Almoravid remnant in Al-Andalus, proclaiming the Almohad Caliphate and extending their rule from the western Sahara and Iberia to Ifriqiya by the turn of the 13th century. Later, the Christians capitalised on internal conflict within the Almohads in 1225 and conquered Iberia by 1228, with the Emirate of Granada assuming control in the south. Following this, the embattled Almohads faced invasions from an Almoravid remnant in the Balearics and gradually lost territory to the Marinids in modern-day Morocco, the Zayyanids in modern-day Algeria, both of Zenata, and the Hafsids of Masmuda in modern-day Tunisia, before finally being extinguished in 1269.[124]: 8–23 Meanwhile, after defeating the Christians' Fifth Crusade in 1221, internal divisions involving Saladin's descendants appeared within the Ayyubid dynasty, crippling the empire's unity.

In 1248, the Christians began the Seventh Crusade with intent to conquer Egypt, but were decisively defeated by the embattled Ayyubids who had relied on Mamluk generals in the face of Mongol expansion. The Ayyubid sultan attempted to alienate the victorious Mamluks, who revolted, killing him and seizing power in Egypt, with rule given to a military caste of Mamluks headed by the Bahri dynasty, whilst the remaining Ayyubid empire was destroyed in the Mongol invasions of the Levant. Following the Mongol Siege of Baghdad in 1258, the Mamluks re-established the Abbasid Caliphate in Cairo, and over the next few decades conquered the Crusader states and, assisted by civil war in the Mongol Empire, defeated the Mongols, before consolidating their rule over the Levant and Syria.[123]: 150–158 To the west, the three dynasties vied for supremacy and control of the trans-Saharan trade. Following the collapse of the Abbasids, the Hafsids were briefly recognised as caliphs by the sharifs of Mecca and the Mamluks. Throughout the 14th century, the Marinids intermittently occupied the Zayyanids several times, and devastated the Hafsids in 1347 and 1357. The Marinids then succumbed to internal division, exacerbated by plague and financial crisis, culminating in the rise of the Wattasid dynasty from Zenata in 1472, with the Hafsids becoming the dominant power.[125]: 34–43 Throughout the 15th century, the Spanish colonised the Canary Isles in the first example of modern settler colonialism, causing the genocide of the native Berber population in the process. To the east, the turn of the 15th century saw the Mamluks oppose the expansionist Ottomans and Timurids in the Middle East, with plague and famine eroding Mamlukian authority, until internal conflict was reconciled. The following decades saw the Mamluks reach their greatest extent with efficacious economic reforms, however the threat of the growing Ottomans and Portuguese trading practices in the Indian Ocean posed great challenges to the empire at the turn of the 16th century.

Nubia

[edit]This section is being written

East Africa

[edit]Horn of Africa

[edit]This section is being written

Swahili coast, Madagascar, and the Comoro Islands

[edit]The turn of the 7th century saw the Swahili coast continue to be inhabited by the Swahili civilisation, whose economies were primarily based on agriculture, however they traded via the Indian Ocean trade and later developed local industries, with their iconic stone architecture.[126]: 587, 607–608 [127] Forested river estuaries created natural harbours whilst the yearly monsoon winds assisted trade,[128][129] and the Swahili civilisation consisted of hundreds of settlements and linked the societies and kingdoms of the interior, such as those of the Zambezi basin and the Great Lakes, to the wider Indian Ocean trade.[130]: 614–615 There is much debate around the chronology of the settlement of Madagascar, although most scholars agree that the island was further settled by Austronesian peoples from the 5th or 7th centuries AD who had proceeded through or around the Indian Ocean by outrigger boats, to also settle the Comoros.[131][132] This second wave possibly found the island of Madagascar sparsely populated by descendants of the first wave a few centuries earlier, with the Vazimba of the interior's highlands being revered and featuring prominently in Malagasy oral traditions.

The wider region underwent an trade expansion from the 7th century, as the Swahili engaged in the flourishing Indian Ocean trade following the early Muslim conquests.[133]: 612–615 Settlements further centralised and some major states included Gedi, Ungwana, Pate, Malindi, Mombasa, and Tanga in the north, Unguja Ukuu on Zanzibar, Kaole, Dar es Salaam, Kilwa, Kiswere, Monapo, Mozambique, and Angoche in the middle, and Quelimane, Sofala, Chibuene, and Inhambane in the south.[134] Via mtumbwi, mtepe and later ngalawa they exported gold, iron, copper, ivory, slaves, pottery, cotton cloth, wood, grain, and rice, and imported silk, glassware, jewellery, Islamic pottery, and Chinese porcelain.[135] Relations between the states fluctuated and varied, with Mombasa, Pate, and Kilwa emerging as the strongest. This prosperity led some Arab and Persian merchants to settle and assimilate into the various societies, and from the 8th to the 14th century the region gradually Islamised due to the increased trading opportunities it brought, with some oral traditions having rulers of Arab or Persian descent.[136]: 605–607 The Kilwa Chronicle, supposedly based on oral tradition, holds that a Persian prince from Shiraz arrived and acquired the island of Kilwa from the local inhabitants, before quarrel with the Bantu king led to the severing Kilwa's land bridge to the mainland. Settlements in northern Madagascar such as Mahilaka, Irodo, and Iharana also engaged in the trade, attracting Arab immigration.[137] Bantu migrated to Madagascar and the Comoros from the 9th century, when zebu were first brought. From the 10th century Kilwa expanded its influence, coming to challenge the dominance of Somalian Mogadishu located to its north, however details of Kilwa's rise remain scarce. In the late 12th century Kilwa wrestled control of Sofala in the south, a key trading city linking to Great Zimbabwe in the interior and famous for its Zimbabwean gold, which was substantial in the usurpation of Mogadishu's hegemony, while also conquering Pemba and Zanzibar. Kilwa's administration consisted of representatives who ranged from governing their assigned cities to fulfilling the role of ambassador in the more powerful ones. Meanwhile the Pate Chronicle has Pate conquering Shanga, Faza, and prosperous Manda, and was at one time led by the popular Fumo Liyongo.[138] The islands of Pemba, Zanzibar, Lamu, Mafia and the Comoros were further settled by Shirazi and grew in importance due to their geographical positions for trade.

By 1100, all regions of Madagascar were inhabited, although the total population remained small.[139]: 48 Societies organised at the behest of hasina, which later evolved to embody kingship, and competed with one another over the island's estuaries, with oral histories describing bloody clashes and earlier settlers often pushed along the coast or inland.[140]: 43, 52–53 An Arab geographer wrote in 1224 that the island consisted of a great many towns and kingdoms, with kings making war on each other.[141]: 51–52 Assisted by climate change, the peoples gradually transformed the island from dense forest to grassland for cultivation and zebu pastoralism. Oral traditions of the central highlands describe encountering an earlier population called the Vazimba, thought to have been the first settlers of Madagsacar, represented as primitive dwarfs.[142]: 71 From the 13th century Muslim settlers arrived, integrating into the respective societies, and held high status owing to Islamic trading networks.

Kilwa had grown by the 15th century to encompass Mombasa, Malindi, Inhambane, Zanzibar, Mafia, Grande Comore, and Mozambique. They first made contact with Portuguese explorers in 1497.[143]

Northern Great Lakes

[edit]This section is being written

West Africa

[edit]The western Sahel and Sudan

[edit]There remains ample room for research on Ghana/Wagadu's expansion and reign, including on the vassals under Ghana, and such details evade our view, however the turn of 6th century saw Ghana continue their dominance.[144] To the west, the Takrur kingdom acceded in the 6th century along the Senegal River, dominating the region, however seeing periods under Ghanaian suzerainty. In the 7th century the Gao Empire of the Songhai people rose in the east to rival Ghana, and had at least seven kingdoms accepting their suzerainty. Gao grew rich through the trans-Saharan trade route linking their capital and Tadmekka with Kairouan in North Africa through commanding the trade of salt, which was used as their currency, and controlled a salt mine north in the Sahara via cavalry.[145] An early written record of Ghana came at the end of the 8th century, mentioning "Ghāna, the land of gold".[146] In 826 a Soninke clan conquered Takrur, installing the Manna dynasty. To the east in northern modern-day Nigeria, Hausa tradition holds that Bayajidda came to Daura in the 9th century, and his descendants founded the kingdoms of Daura, Kano, Rano, Katsina, Gobir, Zazzau, and Biram in the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries, with his bastard descendants founding various others.

Kingdoms in this era were centred around cities and cores, with variations of influence radiating out from these points, meaning there weren't fixed borders.

By the 10th century, the wet period that birthed Ghana was faltering. With the gradual advance of the Sahel at the expense of the Sudan, desert consumed grassland, and epicentres for trade shifted south towards the Niger river, and east from Aoudaghost to Oualata following the shifting of gold source southeast from Bambouk to Bure, strengthening Ghana's vassals while weakening its core. Gao's king converted to Sunni Islam in the early 10th century, having been nominally Muslim prior. At the turn of the 11th century, Ghana expanded north to encompass the Sanhaja trading city of Aoudaghost.[147]: 120–124 In 1054, after having united the Saharan Sanhaja prior to their conquest of the Maghreb, the Almoravid Sanhaja sacked and captured Aoudaghost, at the time a royal seat for Ghana. During this, some of Ghana's vassals achieved independence such as Mema, Sosso, and Diarra/Diafunu, with the last two being especially powerful.[148][149]: 34 Takrur thrived at this time, controlling the gold of Galam, and had close relations with the Almoravids. During this time, the Wolof and Serer in the west resisted the Almoravids and Islamisation. The Almoravids retained influence over Ghana's court for the next few decades, possibly supporting Muslim candidates for the throne, with Ghana converting to Islam in 1076. Oral sources hold that, intent on invading Ghana, which was elsewhere stated to have had a 200,000-man force, the Almoravid army found the king respectful of Islam, and he willingly adopted Islam with the exchange of gold for an Imam relocating to Ghana.[150]: 23–24 Meanwhile in the 11th century, Mossi traditions hold that a princess left Dagbon in the forest region to the south to found Ouagadougou, with her children founding the kingdoms of Tenkodogo, Fada N'Gourma, and Zondoma. Circa 1170, internal conflict within the Ouagadougou dynasty induced the founding of Yatenga to the north, which later conquered Zondoma. After regaining full independence as the Almoravids lost influence in Aoudaghost, Ghana resurged, reasserting suzerainty over their former vassals throughout the 12th century. This was not to reverse the climatic and economic progression however, and at the turn of the 13th century, Sosso, having come under the rule of a general and former slave following dispute within the Diarisso dynasty, united the region and conquered a weakened Ghana from its south, occupying Wagadu and propelling Soninke migration. According to some traditions, Wagadu's fall is caused when a nobleman attempts to save a maiden from sacrifice and kills Bida before escaping the population's ire on horseback, annulling Wagadu and Bida's prior assurance and unleashing a curse causing drought and famine, sometimes causing gold to be discovered in Bure. The Soninke generation that survived the drought were called "it has been hard for them" ("a jara nununa").[151]: 56, 64 The tradition of Gassire's lute is an account of a prince of Wagadu who gives up his ambition to become king, and instead becomes a diari amid the empire's fall.[152]

After the death of his father, Sosso's Soumaoro Kante forced Wagadu to accept their suzerainty, and he conquered Diarra, Gajaaga, vassalized Takrur, and subdued the Mandinka clans of Manden, who were early adopters of Islam, to the south where the goldfield of Bure was located. In accordance with the traditional Epic of Sundiata, Sundiata Keita, a prince of local origin but in exile, held a position in the former Ghanaian vassal of Mema and returned to Manden aided by the king of Mema to relieve his people of the tyrannical Sosso king. Sundiata allied and pacified the Madinka clans, and defeated Soumaoro Kante in battle in 1235, and conquered Kante's ally Diarra, proclaiming the Kouroukan Fouga of the nascent Mali Empire. Allied kingdoms, including Mema and Wagadu, retained leadership of their province, whilst conquered leaders were assigned a farin subordinate to the mansa (king/emperor), with provinces retaining a great deal of autonomy. At the same time as Sundiata's campaigns in the north subjugating ancient Ghana's former vassals, the Malian military campaigned to the west in Bambouk and against the Fula in the highlands of Fouta Djallon. Sundiata saw to equip the army with horses purchased from the western kingdom of Kita, however the Wolof king arrested Mandinka caravan traders, inflaming conflict which culminated in the conquest of the Wolof and Serer. This extended the empire to the Atlantic coast in modern-day Senegal, with the Malian general continuing to campaign in the west in Casamance and against the Bainuk and Jola kings in the highlands of Kaabu, forming various subordinate kingdoms. Sundiata passed in 1255 and his son conquered Gajaaga and Takrur, and brought the key Saharan trading centres under his rule. The cessation of his reign culminated in a destructive civil war, only reconciled with a militaristic coup, after which Gao was conquered and the Tuareg subdued, cementing Mali's dominance over the trans-Saharan trade.[153]: 126–147 In 1312 Mansa Musa came to power in Mali after his predecessor had set out on an Atlantic voyage. Musa supposedly spent much of his early campaign preparing for his infamous hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca. Between 1324 and 1325 his entourage of 60,000 men, including 12,000 slaves, and hundreds of camels, all carrying around 18 tonnes of gold in total,[154] travelled 2700 miles, giving gifts to the poor along the way, and fostered good relations with the Mamluk sultan, garnering widespread attention in the Muslim world. On Musa's return, his general reasserted dominance over Gao and he commissioned a large construction program, building mosques and madrasas, with Timbuktu becoming a centre for trade and Islamic scholarship, however Musa features comparatively less than his predecessors in the Mandinka oral traditions than in modern histories.[153]: 147–152 Despite Mali's fame being attributed to its riches in gold, Mali's prosperous economy was based on arable and pastoral farming, as well as crafts, and they traded commonly with the Akan, Dyula, and with Benin, Ife, and Nri in the forest regions.[153]: 164–171 To the east, the Kano king converted to Islam in 1349 after da'wah (invitation) from some Soninke Wangara, and later absorbed Rano.[153]: 171

Amid a Malian mansa's successful attempt to coerce the empire back into financial shape after the lacklustre premiership of his predecessor, Mali's northwestern-most province broke away to form the Jolof Empire and the Serer kingdoms. Wolof tradition holds that the empire was founded by the wise Ndiadiane Ndiaye, and it later absorbed neighbouring kingdoms to form a confederacy of the Wolof kingdoms of Jolof, Cayor, Baol, and Waalo, and the Serer kingdoms of Sine and Saloum. In Mali after the death of Musa II in 1387, vicious conflict ensued within the Keita dynasty. In the 1390s Yatenga sacked and raided the southern trading city of Macina in Mali. The internal conflict weakened Mali's central authority. This provided an opportunity for the previously subdued Tuareg tribal confederations in the Sahara to rebel. Over the next few decades they captured the main trading cities of Timbuktu, Oualata, Nema, and possibly Gao, with some tribes forming the northeastern Sultanate of Agadez, and with them all usurping Mali's dominance over the trans-Saharan trade.[155]: 174 In the 15th century, the Portuguese, following the development of the caravel, set up trading posts along the Atlantic coast, with Mali establishing formal commercial relations, and the Spanish soon following. In the early 15th century Diarra escaped Malian rule.[156]: 130 Previously under Malian suzerainty and under pressure from the expansionist Jolof Empire, a Fula chief migrated to Futa Toro, founding Futa Kingui in the lands of Diarra circa 1450. Yatenga capitalised on Mali's decline and conquered Macina, and the old province of Wagadu. Meanwhile Gao, ruled by the Sonni dynasty, expanded, conquering Mema from Mali, in a struggle over the crumbling empire.

Within the Niger bend and the forest region

[edit]This section is being written

Central Africa

[edit]The central Sahel

[edit]This section is being written

The Congo basin and Cameroon

[edit]This section is being written

Southern Africa

[edit]Southern Great Lakes and the Zambezi basin

[edit]This section is being written

South of the Zambezi basin

[edit]This section is being written

16th century–1870

[edit]Colonial period (1870–1951)

[edit]Between 1878 and 1898, European states partitioned and conquered most of Africa. For 400 years, European nations had mainly limited their involvement to trading stations on the African coast, with few daring to venture inland. The Industrial Revolution in Europe produced several technological innovations which assisted them in overcoming this 400-year pattern. One was the development of repeating rifles, which were easier and quicker to load than muskets. Artillery was being used increasingly. In 1885, Hiram S. Maxim developed the maxim gun, the model of the modern-day machine gun. European states kept these weapons largely among themselves by refusing to sell these weapons to African leaders.[157]

African germs took numerous European lives and deterred permanent settlements. Diseases such as yellow fever, sleeping sickness, yaws, and leprosy made Africa a very inhospitable place for Europeans. The deadliest disease was malaria, endemic throughout Tropical Africa. In 1854, the discovery of quinine and other medical innovations helped to make conquest and colonization in Africa possible.[158]

There were strong motives for conquest of Africa. Raw materials were needed for European factories. Prestige and imperial rivalries were at play. Acquiring African colonies would show rivals that a nation was powerful and significant. These contextual factors forged the Scramble for Africa.[159]

In the 1880s the European powers had carved up almost all of Africa (only Ethiopia and Liberia were independent). The Europeans were captivated by the philosophies of eugenics and Social Darwinism, and some attempted to justify all this by branding it civilising missions. Imperialism ruled until after World War II when forces of African nationalism grew stronger. In the 1950s and 1960s the colonial holdings became independent states. The process was usually peaceful but there were several long bitter bloody civil wars, as in Algeria,[160] Kenya,[161] and elsewhere. Across Africa the powerful new force of nationalism drew upon the advanced militaristic skills that natives learned during the world wars serving in the British, French, and other armies. It led to organizations that were not controlled by or endorsed by either the colonial powers nor the traditional local power structures that had collaborated with the colonial powers. Nationalistic organizations began to challenge both the traditional and the new colonial structures, and finally displaced them. Leaders of nationalist movements took control when the European authorities evacuated; many ruled for decades or until they died. These structures involved political, educational, religious, and other social organizations. In recent decades, many African countries have undergone the triumph and defeat of nationalistic fervour, changing in the process the loci of the centralizing state power and patrimonial state.[162][163][164]

1951 – present

[edit]

The wave of decolonization of Africa started with Libya in 1951, although Liberia, South Africa, Egypt and Ethiopia were already independent. Many countries followed in the 1950s and 1960s, with a peak in 1960 with the Year of Africa, which saw 17 African nations declare independence, including a large part of French West Africa. Most of the remaining countries gained independence throughout the 1960s, although some colonizers (Portugal in particular) were reluctant to relinquish sovereignty, resulting in bitter wars of independence which lasted for a decade or more. The last African countries to gain formal independence were Guinea-Bissau (1974), Mozambique (1975) and Angola (1975) from Portugal; Djibouti from France in 1977; Zimbabwe from the United Kingdom in 1980; and Namibia from South Africa in 1990. Eritrea later split off from Ethiopia in 1993.[165] The nascent countries decided to keep their colonial borders in the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) conference of 1964 due to fears of civil wars and regional instability, and placed emphasis on Pan-Africanism, with the OAU later developing into the African Union.[166] During the 1990s and early 2000s there were the First and Second Congo Wars, often termed the African World Wars.[167][168]

Historiography

[edit]Colonial historiography

[edit]The academic discipline of history arrived with the arrival of Europeans from the 16th century and the conquest and colonisation of Africa and involved the study of Africa and its history by European academics and historians.[169] Prior to colonisation in the 19th century, most African societies chose to use oral tradition to record their history, including in cases where they had developed or had access to a writing script, meaning there was little written history, and the domination of European powers across the continent meant African history was written from an entirely European perspective under the pretence of Western superiority.[170] This lack of written history, unfamiliar mediums, and concealment behind a multitude of dialects and languages led to a perception by Europeans that Africa and its people had no recorded history and little desire to create it.[171] The historical works of the time were predominantly written by scholars of the various European powers and were confined to individual nations, leading to disparities in style, quality, language and content between the many African nations.[169]

Postcolonial historiography

[edit]Post-colonialist historiography studies the relationship between European colonialism and domination in Africa and the construction of African history and representation. It has roots in Orientalism, the construction of cultures from the Asian, Arabian and North African world in a patronizing manner stemming from a sense of Western superiority, first theorized by Edward Said.[172] A general perception of Western superiority throughout European academics and historians prominent during the height of colonialism led to the defining traits of colonial historical works, which post-colonialists have sought to analyse and criticize. Examples of general histories of Africa include The Cambridge History of Africa (1975–1986) and the General History of Africa published by UNESCO (1981–2024).

Contemporary historiography

[edit]Acknowledgement and acceptance of African nations and peoples as individuals free of European domination has allowed African history to be approached from new perspectives and with new methods. Africa has lacked a defined means of communication or academic body due to its variety of cultures and communities, and the plurality and diversity of its many peoples means a historiographical approach that confines itself to the development and activity of a singular people or nation incapable of capturing the comprehensive history of African nations without a vast quantity of historical works.[173] There have also been strides made in the study of oral traditions. This quantity and diversity of history that has yet to be documented is better suited to the contemporary historiographical movements that incorporate the social sciences: anthropology, sociology, geography and other fields that closer examine the human element of History rather than constrain it to political history.

See also

[edit]- Architecture of Africa

- History of science and technology in Africa

- Military history of Africa

- Genetic history of Africa

- Economic history of Africa

- African historiography

- List of history journals#Africa

- List of kingdoms in Africa throughout history

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Africa

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Recordkeeping and History". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "Early African Civilization". Study.com. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "History of Africa". Visit Africa. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ^ Southall, Aidan (1974). "State Formation in Africa". Annual Review of Anthropology. 3: 153–165. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.03.100174.001101. JSTOR 2949286.

- ^ Meyerowitz, Eva L. R. (1975). The Early History of the Akan States of Ghana. Red Candle Press. ISBN 978-0-608390352.

- ^ Boyes, Steve (October 31, 2013). "Getting to Know Africa: 50 Interesting Facts". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2013-12-27.

- ^ Stilwell, Sean (2013). "Slavery in African History". Slavery and Slaving in African History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139034999.003. ISBN 978-1-139-03499-9.

For most Africans between 10000 BCE to 500 CE, the use of slaves was not an optimal political or economic strategy. But in some places, Africans came to see the value of slavery. In the large parts of the continent where Africans lived in relatively decentralized and small-scale communities, some big men used slavery to grab power to get around broader governing ideas about reciprocity and kinship, but were still bound by those ideas to some degree. In other parts of the continent early political centralization and commercialization led to expanded use of slaves as soldiers, officials, and workers.

- ^ Lovejoy, Paul E. (2012). Transformations of Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. London: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Sparks, Randy J. (2014). "4. The Process of Enslavement at Annamaboe". Where the Negroes are Masters : An African Port in the Era of the Slave Trade. Harvard University Press. pp. 122–161. ISBN 9780674724877.

- ^ Ronald Segal, The Black Diaspora: Five Centuries of the Black Experience Outside Africa (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), ISBN 0-374-11396-3, p. 4. "It is now estimated that 11,863,000 slaves were shipped across the Atlantic." (Note in original: Paul E. Lovejoy, "The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa: A Review of the Literature", in Journal of African History 30 (1989), p. 368.)

- ^ Patrick Manning, "The Slave Trade: The Formal Dermographics of a Global System" in Joseph E. Inikori and Stanley L. Engerman (eds), The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe (Duke University Press, 1992), pp. 117–44, online at pp. 119–20.

- ^ Chukwu, Lawson; Akpowoghaha, G. N. (2023). "Colonialism in Africa: An Introductory Review". Political Economy of Colonial Relations and Crisis of Contemporary African Diplomacy. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-0245-3_1. ISBN 978-981-99-0244-6.

- ^ Frankema, Ewout (2018). "An Economic Rationale for the West African Scramble? The Commercial Transition and the Commodity Price Boom of 1835–1885". The Journal for Economic History. 78 (1): 231–267. doi:10.1017/S0022050718000128.

- ^ Mamdani, Mahmood (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (1st ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691027937.

- ^ Walls, A (2011). "African Christianity in the History of Religions". Studies in World Christianity. 2 (2). Edinburgh University Press: 183–203. doi:10.3366/swc.1996.2.2.183.

- ^ Hargreaves, John D. (1996). Decolonization in Africa (2nd ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-24917-1. OCLC 33131573.

- ^ Shillington (2005), p. 2.

- ^ Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano; Harvati, Katerina; Gunz, Philipp (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953. S2CID 256771372.

- ^ Scerri, Eleanor M. L.; Thomas, Mark G.; Manica, Andrea; Gunz, Philipp; Stock, Jay T.; Stringer, Chris; Grove, Matt; Groucutt, Huw S.; Timmermann, Axel; Rightmire, G. Philip; d'Errico, Francesco (1 August 2018). "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (8): 582–594. Bibcode:2018TEcoE..33..582S. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 6092560. PMID 30007846.

- ^ Vidal, Celine M.; Lane, Christine S.; Asfawrossen, Asrat; et al. (January 2022). "Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa". Nature. 601 (7894): 579–583. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..579V. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04275-8. PMC 8791829. PMID 35022610.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (10 September 2019). "Scientists Find the Skull of Humanity's Ancestor – on a Computer – By comparing fossils and CT scans, researchers say they have reconstructed the skull of the last common forebear of modern humans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-03. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Mounier, Aurélien; Lahr, Marta (2019). "Deciphering African late middle Pleistocene hominin diversity and the origin of our species". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 3406. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.3406M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-11213-w. PMC 6736881. PMID 31506422.

- ^ Henshilwood, Christopher; et al. (2002). "Emergence of Modern Human Behavior: Middle Stone Age Engravings from South Africa". Science. 295 (5558): 1278–1280. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1278H. doi:10.1126/science.1067575. PMID 11786608. S2CID 31169551.

- ^ Henshilwood, Christopher S.; d'Errico, Francesco; Watts, Ian (2009). "Engraved ochres from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa". Journal of Human Evolution. 57 (1): 27–47. Bibcode:2009JHumE..57...27H. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.01.005. PMID 19487016.

- ^ Texier, PJ; Porraz, G; Parkington, J; Rigaud, JP; Poggenpoel, C; Miller, C; Tribolo, C; Cartwright, C; Coudenneau, A; Klein, R; Steele, T; Verna, C (2010). "A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (14): 6180–6185. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6180T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913047107. PMC 2851956. PMID 20194764.

- ^ McBrearty, Sally; Brooks, Allison (2000). "The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (5): 453–563. Bibcode:2000JHumE..39..453M. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0435. PMID 11102266.

- ^ Henshilwood, Christopher S.; et al. (2004). "Middle Stone Age shell beads from South Africa". Science. 304 (5669): 404. doi:10.1126/science.1095905. PMID 15087540. S2CID 32356688.

- ^ d'Errico, Francesco; et al. (2005). "Nassarius kraussianus shell beads from Blombos Cave: evidence for symbolic behaviour in the Middle Stone Age". Journal of Human Evolution. 48 (1): 3–24. Bibcode:2005JHumE..48....3D. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.09.002. PMID 15656934.

- ^ Vanhaeren, Marian; et al. (2013). "Thinking strings: Additional evidence for personal ornament use in the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa". Journal of Human Evolution. 64 (6): 500–517. Bibcode:2013JHumE..64..500V. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.02.001. PMID 23498114.

- ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik M, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, Valentin F, Thevenet C, Furtwängler A, Wißing C, Francken M, Malina M, Bolus M, Lari M, Gigli E, Capecchi G, Crevecoeur I, Beauval C, Flas D, Germonpré M, van der Plicht J, Cottiaux R, Gély B, Ronchitelli A, Wehrberger K, Grigorescu D, Svoboda J, Semal P, Caramelli D, Bocherens H, Harvati K, Conard NJ, Haak W, Powell A, Krause J (2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..827P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362.

- ^ Kamin M, Saag L, Vincente M, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Vai S, Sarno S, Lari M, Luiselli D, Manzi G, Gallinaro M, Mataich S, Hübner A, Modi A, Pilli E, Tafuri MA, Caramelli D, di Lernia S (March 2019). "Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara". Sci Rep. 9 (1): 3530. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.3530V. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39802-1. PMC 6401177. PMID 30837540.

- ^ Haber M, Jones AL, Connel BA, Asan, Arciero E, Huanming Y, Thomas MG, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C (June 2019). "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-chromosomal Haplogroup and its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics. 212 (4): 1421–1428. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMC 6707464. PMID 31196864.

- ^ Shillington (2005), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Genetic studies by Luca Cavalli-Sforza pioneered tracing the spread of modern humans from Africa.

- ^ Tishkoff, Sarah A.; Reed, Floyd A.; Friedlaender, Françoise R.; Ehret, Christopher; Ranciaro, Alessia; Froment, Alain; Hirbo, Jibril B.; Awomoyi, Agnes A.; Bodo, Jean-Marie; Doumbo, Ogobara; Ibrahim, Muntaser; Juma, Abdalla T.; Kotze, Maritha J.; Lema, Godfrey; Moore, Jason H.; Mortensen, Holly; Nyambo, Thomas B.; Omar, Sabah A.; Powell, Kweli; Pretorius, Gideon S.; Smith, Michael W.; Thera, Mahamadou A.; Wambebe, Charles; Weber, James L. & Williams, Scott M. (22 May 2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–1044. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1035T. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.

- ^ a b Vicente, Mário; Schlebusch, Carina M (2020-06-01). "African population history: an ancient DNA perspective". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Genetics of Human Origin. 62: 8–15. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2020.05.008. ISSN 0959-437X. PMID 32563853. S2CID 219974966.

- ^ Osypiński, Piotr; Osypińska, Marta; Gautier, Achilles (2011). "Affad 23, a Late Middle Palaeolithic Site With Refitted Lithics and Animal Remains in the Southern Dongola Reach, Sudan". Journal of African Archaeology. 9 (2): 177–188. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10186. ISSN 1612-1651. JSTOR 43135549. OCLC 7787802958. S2CID 161078189.