South of Market, San Francisco

SoMa | |

|---|---|

Buildings in the South of Market neighborhood | |

| Nickname: SoMa | |

| Coordinates: 37°46′38″N 122°24′40″W / 37.77722°N 122.41111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| City-county | San Francisco |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Matt Dorsey |

| • Assemblymember | Matt Haney (D)[1] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.635 sq mi (1.64 km2) |

| • Land | 0.635 sq mi (1.64 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 11,457 |

| • Density | 18,000/sq mi (7,000/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 94103 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

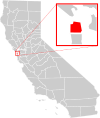

South of Market (SoMa) is a neighborhood in San Francisco, California, situated just south of Market Street. It contains several sub-neighborhoods including South Beach, Yerba Buena, and Rincon Hill.

SoMa is home to many of the city's museums, to the headquarters of several major software and Internet companies, and to the Moscone Conference Center.

Name and location[edit]

The area's boundaries are Market Street to the northwest, San Francisco Bay to the northeast, Mission Creek to the southeast, and Division Street, 13th Street and U.S. Route 101 (Central Freeway) to the southwest.[4] It is the part of the city in which the street grid runs parallel and perpendicular to Market Street. The neighborhood includes many smaller sub-neighborhoods such as: South Park, Yerba Buena,[5] South Beach, and Financial District South (part of the Financial District), and overlaps with several others, notably Mission Bay, and the Mission District.

As with many neighborhoods, the precise boundaries of the South of Market area are fuzzy and can vary widely depending on the authority cited. From 1848 until the construction of the Central Freeway in the 1950s, 9th Street (formerly known as Johnston Street) was the official (and generally recognized) boundary between SoMa and the Mission District.[6][7] Since the 1950s, the boundary has been either 10th Street, 11th Street,[8] or the Central Freeway. Similarly, the entire Mission Bay neighborhood may or may not be counted as part of SoMa,[9] Excluding the entire Mission Bay neighborhood puts the southeastern boundary at Townsend. Redevelopment agencies, social service agencies, and community activists frequently exclude the more prosperous areas between the waterfront and 3rd Street. Some social service agencies and nonprofits count the economically distressed area around 6th, 7th, and 8th streets as part of the Mid-Market Corridor. [citation needed]

The terms "South of Market" and "SoMa" refer to both a comparatively large district of the city[10] as well as a much smaller neighborhood.[11]

While many San Franciscans refer to the neighborhood by its full name, South of Market, there is a trend to shorten the name to SOMA or SoMa, probably[citation needed] in reference to SoHo (South of Houston) in New York City, and, in turn, Soho in London.

Before being called South of Market this area was called "South of the Slot", a reference to the cable cars that ran up and down Market along the slots through which they gripped cables. While the cable cars have long since disappeared from Market Street, some "old timers" still refer to this area as "South of the Slot".[8]

Since 1847 [citation needed], the official name of the South of Market area has been the "100 Vara Survey" (alternately "100 Vara District") or simply "100 Vara" for short (with "100" sometimes spelled out). The "100 Vara Survey" derived its name from the surface area of the single lots which comprised 100 by 100 varas (275 square feet).[12]

According to city documents from 1945,[13] the "100 Vara District" goes from the south side of Market Street to the Ferry. The name is found mainly in history books, legal documents,[14] title deeds, and civil engineering reports.[15]

History[edit]

In 1847 Washington A. Bartlett, alcalde (magistrate) of the pueblo (village) of San Francisco, commissioned surveyor Jasper O'Farrell to extend the boundaries of the pueblo in a southerly direction by creating a new subdivision. At the time, the streets of San Francisco were aligned approximately with the compass points, running north to south, or east to west. Each block was divided into six lots 50 varas on a side. (A vara is about 33 inches (84 cm).) O'Farrell decided that the streets in the new subdivision should run parallel with or perpendicular to the only existing road in the area, Mission Road (later Mission Street), and thus be aligned with the half-points of the compass, i.e., northeast to southwest, and northwest to southeast. He also decided to make the new blocks twice as long and twice as wide, with each lot 100 varas on a side. Finally, O'Farrell created "a grand promenade" linking the old pueblo with the new subdivision, Market Street.[16] Since then, downtown San Francisco north of Lower Market Street has been officially known as 50 Vara, while the South of Market area is officially known as 100 Vara.[13]

During the mid-19th century, SOMA became a burgeoning pioneer community, consisting largely of low-density residential buildings, except for a business district that developed along 2nd and 3rd streets, and emerging industrial areas near the waterfront. Rincon Hill became an enclave for the wealthy, while nearby South Park became an enclave for the upper middle class.[17] By the early 20th century, heavy industrial development due to its proximity to the docks of San Francisco Bay, coupled with the advent of cable cars, had driven the wealthy over to Nob Hill and points west. The neighborhood became a largely working-class and lower-middle-class community of recent European immigrants, sweatshops, power stations, flophouses, and factories.[citation needed]

The 1906 earthquake completely destroyed the area, and many of the quake's fatalities occurred there. Following the quake, the area was rebuilt with wider than usual streets, as the focus was on the development of light to heavy industry. The construction of the Bay Bridge and U.S. Route 101 during the 1930s saw large swaths of the area demolished, including most of the original Rincon Hill.[18]

From the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, the South of Market area was served by several streetcar lines owned by the Market Street Railway Company, including the No. 14 Mission Street electric railway line, the No. 27 Bryant Street line, the 28 Harrison, 35 Howard, 36 Folsom, 41 Second and Market, and the No. 42 First and Fifth Street line.[19]

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, South of Market was home not only to warehousing and light industry, but also to a sizable population of transients, seamen, other working men living in hotels, and a working-class residential population in old Victorian buildings on smaller side streets and alleyways giving it a "skid row" reputation.[20]

"South of Market in the land of ruin

You get all manner of action

Tinsel tigers in The Metal Room

Stalking satisfaction.

They got 'em packaged up for love and money

Tattooed tots and chrome spike bunnies

Check my conscience at the DMZ

And roll on in, gonna roll in it, honey

But I get a feelin like when big things collide

Like the crack before the thunder, like I really ought to hide

And here comes Metal Angel, she looks ready to ride;

& What's that she's tryin' to show me..?

What's that you're tryin' to show me..?"

Grateful Dead, Picasso Moon (1989)[21]

The waterfront redevelopment of the Embarcadero in the 1950s pushed a new population into this area in the 1960s, the incipient gay community, and the leather community in particular. The Tool Box at 399 Forth Street was the first leather bar in South of Market, opening in 1962.[4] From 1962 until 1982, the gay leather community grew and thrived throughout South of Market, most visibly along Folsom Street, since it was a warehouse area that was largely deserted at night.[22] Site of various sex clubs and bars, such as the Caldron and the Slot, it was the sexual center of San Francisco during this period.[23][24] This community had been active in resisting the city's ambitious redevelopment program for the area throughout the 1970s. But as the AIDS epidemic unfolded in the 1980s, the ability of this community to stand up to downtown and City Hall was dramatically weakened. The crisis became an opportunity for the city (in the name of public health) to close bathhouses and regulate bars - businesses that had been the cornerstone of the community's efforts to maintain a gay space in the South of Market neighborhood.[20]

In 1984, as these spaces for the gay community were rapidly closing, a coalition of housing activists and community organizers started the Folsom Street Fair, in order to enhance the visibility of the community at a time when people in City Hall and elsewhere were apt to think it had gone away. The fair also provided a means for much-needed fundraising, and created opportunities for members of the leather community to connect to services and vital information (e.g., regarding safer sex) which bathhouses and bars might otherwise have been ideally situated to distribute.[20]

Redevelopment plans were first outlined in 1953. These plans began to be realized in the late 1970s and in the early 1980s with the construction of the conference center, Moscone Center, which occupies three blocks and hosts many major trade shows. Moscone South opened its doors in December 1981. Moscone North opened in May 1992, and most recently Moscone West in June 2003.

With the opening of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1995, the Mission and Howard Street area of the South of Market has become a hub for museums and performances spaces. Intersection for the Arts is also based in the neighborhood, a non-profit which supports local Bay Area artists. The San Francisco institution was founded in 1965 in the Tenderloin, but has moved within the city to its current location in SoMa. Intersection supports the arts by offering local artists resources, fiscal sponsorship, and exhibition and performance spaces.

The area has long been home to bars and nightclubs. During the 1980s and 1990s, some of the warehouses there served as the home to the city's budding underground rave, punk, and independent music scene. However, in recent decades, and mostly due to gentrification and rising rents, these establishments have begun to cater to an upscale and mainstream clientele that subsequently pushed out the underground musicians and their scene. Beginning in the 1990s, older housing stock has been joined by loft-style condominiums. Many of these were built under the cover of "live-work" development ostensibly meant to maintain a studio arts community in San Francisco. During the late 1990s, the occupant of the "live-work" loft was more likely to be a "dot-commie", as South of Market became a local center of the dot-com boom, due to its central location, space for infill housing development, and spaces readily converted into offices.[25]

A major transformation of the neighborhood was conceived during the 2000s with the Transbay Terminal Replacement Project, which broke ground in August 2010 and opened in August 2018. In addition, new high rise residential projects like One Rincon Hill, 300 Spear Street, and Millennium Tower are transforming the San Francisco skyline. In 2005, the Transbay Joint Powers Authority proposed to raise height limits around the new Transbay Terminal.[26] This led to proposals for more supertall buildings, such as Renzo Piano's proposal for a group of towers that includes two 1,200-foot. (366 m) towers, two 900-foot (274 m) towers, and a 600-foot (183 m) tower. The 1,200-foot (366 m) towers would have been the tallest buildings in the United States outside of New York City and Chicago.[27][28] Renzo Piano's complex has since been canceled, and replaced by a newer project entitled 50 First Street, to be designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). In addition, the Cesar Pelli and Hines Group have also proposed another 1,070-foot (366 m), 61-story office tower.[29] The Salesforce Tower, formerly named the Transbay Tower, was completed May 2018.

Economy[edit]

The neighborhood consists of warehouses, auto repair shops, nightclubs, residential hotels, art spaces, loft apartments, furniture showrooms, condominiums and technology companies.[30] A major children's park was also built for the area on top of Moscone South. The park features a large play area, an ice skating rink, a bowling alley, a restaurant, the Children's Creativity Museum[31] and the restored carousel[32] from Playland-At-the-Beach. The children's park and Children's Creativity Museum are joined to the Yerba Buena Gardens by a footbridge.

Businesses[edit]

Many major software and technology companies have headquarters and offices here, including Ustream,[33] Planet Labs,[34] Foursquare,[35] Cloudflare,[36][37] Wikia,[citation needed] Wired, GitHub, Pinterest,[38] CBS Interactive,[39] LinkedIn, Trulia, Dropbox,[40] IGN, Salesforce,[41] BitTorrent Inc., Yelp,[42] Zynga,[43] Airbnb,[44] Uber,[45] Advent Software,[46][47] Pac-12 Networks,[48] Okta,[49][50] and Yeti.[citation needed] The area is also home to the few big-box stores within San Francisco.

Public health[edit]

The South of Market Health Center ensured health care access to comprehensive care by providing mental and physical health problem services to close the gap on health disparities.[51] It provides agencies with programs including finances, health care, food assistance or job training. In terms of sexual health, the district's San Francisco City Clinic offers sexually transmitted disease (STD) tests and treatment, in addition to counseling and condoms.

211 United Way Bay Area is a service that connects callers with services and programs: including basic needs, physical and mental health, employment assistance, and seniors support.[52]

Miscellaneous attractions[edit]

The local Academy of Art University owns several buildings in the neighborhood, primarily for academic and administrative purposes.[53]

Culture[edit]

Cultural centers[edit]

SOMA is home to many of San Francisco's museums, including San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA),[54] the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts,[55] the Museum of the African Diaspora,[56] the American Bookbinders Museum, the California Historical Society, the Zeum, and the Contemporary Jewish Museum.[57] The Old Mint, which served as the San Francisco Mint from 1874 to 1937, was restored over an eight-year period and reopened to the public in 2012. The Center for the Arts, along with Yerba Buena Gardens and the Metreon, is built on top of Moscone North.

SOMArts, one of four cultural center facilities owned by the City and County of San Francisco, is located on Brannan Street between 8th and 9th streets.[58]

Many small theater companies and venues are situated in the SOMA, including the Lamplighters,[59] The Garage,[60] Theatre Rhinoceros,[61] Boxcar Theater,[62] Crowded Fire Theater,[63] and FoolsFURY Theater.[64]

Events[edit]

Due to the area's gay rights history, the Folsom Street Fair is held on Folsom St between 7th and 12th Streets (now between 8th and 13th Streets).[65] The smaller and less-commercialized leather subculture-oriented Up Your Alley Fair (commonly referred to as the Dore Alley Fair) is held in late July on and around Folsom St.[66] Also home to the annual How Weird Street Faire featuring dancing and costumes, held in early May along seven city blocks including Howard and Second streets.[67]

Several Filipino cultural events are held such as Filipino American History Month Celebration at the Asian Art Museum in October and Pistahan Parade and Festival in August.

Undiscovered SF, held monthly, promotes economic activity and awareness of SoMa Pilipinas. It supports retail concepts, restaurants, and businesses by giving skill-set building workshops and professional services like accounting and crowdfunding to prepare businesses for growth and sustainability.[68]

Leather and LGBTQ Cultural District[edit]

The Leather and LGBTQ Cultural District was created in SoMa in 2018.[69] The area is bounded approximately by Howard St. on the northwest, 7th St. on the northeast, I-80 on the east and US 101 on the south. There is also an exclave between 5th and 6th streets, Harrison and Bryant.[70] It includes the San Francisco South of Market Leather History Alley, which opened in 2017.[71][72]

SoMa Pilipinas[edit]

In April 2016, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors adopted a resolution that established the SOMA Pilipinas Filipino Cultural Heritage District.[73] The relationship between SOMA Pilipinas and the Philippines is established in the resolution: "Whereas, Filipino immigration patterns to San Francisco are rooted in the conquest and subsequent colonization of the Philippines by the United States in 1898, the American colonial regime in the Philippines from 1899-1946, and ongoing, often unequal and imperialist US-Philippines relations from 1946 to present."[74] The City of San Francisco certified Tagalog as its third official language in 2014, and a 2010 Census illustrated the Filipino population to reach 36,347 Filipino in the city which 5,106 live in South of Market District. Within the SOMA Pilipinas' official borders—Market to the north, Brannan to the south, 2nd the east, and 11th to the west—are several streets named after Filipino historical figures, including Rizal, Lapu-Lapu, and Mabini, and are located between Folsom and Harrison Streets. A former Filipino district existed near North Beach, prior to its gentrification, called Manilatown.

See also[edit]

- List of tallest buildings in San Francisco

- Moscone Center

- Foundry Square

- San Francisco Transbay development

- Transbay Terminal

- Salesforce Tower

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "South Of Market (SOMA) neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94103 subdivision profile – real estate, apartments, condos, homes, community, population, jobs, income, streets". City-data.com. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "SF Planning Dept., Historic Context Statement South of Market Area (2009)". Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "Neighborhood Map". Yerba Buena Alliance.

- ^ Zoeth Skinner Eldredge, The beginnings of San Francisco, vol. 2, pp. 740-741

- ^ "Mery's Block Book of San Francisco (1909)". Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "SoMa — San Francisco Neighborhoods — Travel — SFGate". The San Francisco Chronicle. October 26, 2011.

- ^ Crawford, Sabrina (January 31, 2006). Sabrina Crawford, Newcomer's Handbook for Moving to And Living in the San Francisco Bay Area, p. 51. ISBN 9780912301631. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Justinsomnia.org SF neighborhood map

- ^ San Francisco Planning Dept. - General Plan - South of Market Planning Area, map 1 Archived June 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "California Historical Quarterly". 1972.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Journal of proceedings, Board of Supervisors, City and County of San Francisco, Volume 40, Issue 1 (January 1945), p. 46". Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "block book page from the County Recorder-Assessor's Office showing Block 3775 (100 Vara Block 359, i.e., South Park)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "Thomas G. Matoff, Memorandum to SFMTA dated April 27, 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Theodore Henry Hittell, History of California, Volume 2 (1897) pp. 596-7

- ^ "View from Rincon Hill, 1856". Foundsf.org. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "Rincon Hill Area Plan". City & County of San Francisco. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Hoffman, Philip; Ute, Grant (March 1, 2005). Walt Vielbaum, Philip Hoffman, Grant Ute, San Francisco's Market Street Railway, pp. 4, 7. Arcadia. ISBN 9780738529677. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rubin, Gayle. "The Miracle Mile: South of Market and Gay Male Leather, 1962-1997" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture (City Light Books, 1998).

- ^ "The Annotated "Picasso Moon"". Artsites.ucsc.edu. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Mick Sinclair, San Francisco: A Cultural and Literary History, Interlink, 2003, ISBN 1566564891, p. 220

- ^ Gayle S. Rubin, "The Miracle Mile. South of Market and Gay Male Leather, 1962-1997", in Recllaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture, edited by James Brook, Chris Carlsson, Nancy J. Peters, San Francisco, City Lights, 2001, ISBN 0872863352, pp. 247-272.

- ^ Bajko, Matthew S. (September 22, 2005). "Tour digs up SOMA's gay past". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ "36 Hours in SoMa, San Francisco" "36 Hours in SoMa, San Francisco - New York Times". Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- ^ Fancher, Emily (May 26, 2006). "Transbay proposal includes possible tallest building on West Coast". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ King, John (December 21, 2006). "Proposal to build two massive towers in SF". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ King, John (December 22, 2006). "Sky's the limit South of Market 4 of developers' proposed high-rises would've taller than anything else in S.F." San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ King, John (September 21, 2007). "'Aggressive schedule' for proposed Transbay transit center, tower". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ "South of Market Business Association Directory". SOMBA South of Market Business Association. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Children's Creativity Museum". Children's Creativity Museum. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Yerba Buena Gardens Map". Yerba Buenna Gardens. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Patrick Hoge (April 20, 2012). "Ustream downsizes S.F. offices". San Francisco Business Times. American City Business Journals. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Planet Labs Raises $95 Million Financing". SpaceRef. SpaceRef Interactive Inc. January 20, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Alexia Tsotsis (June 10, 2011). "Foursquare (Finally) Checks In To Its Very Own SOMA Office [Pics]". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Terms of Service." Cloudflare. Retrieved on August 3, 2015. "665 3rd St. #200 San Francisco, CA 94107 USA"

- ^ "Contact." Founders Den. Retrieved on August 3, 2015. "Founders Den is located in an 8500 sqft facility in the heart of SoMa[...]665 3rd St., Suite 150, San Francisco, CA 94107."

- ^ Michael (May 2014). "Pinterest's trendy headquarters in San Francisco's SoMa neighborhood". Officelovin'. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ J.K. Dineen (October 30, 2013). "A decade in the making, SoMa's Foundry Square nears completion". San Francisco Business Times. American City Business Journals. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Dropbox Leases 100% of Kilroy Realty's New Office Development Project at 333 Brannan Street in San Francisco's SOMA District" (Press release). Business Wire. February 3, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Andrew Dalton (April 22, 2014). "LinkedIn Plans To Lease Entire 26-Story Office Tower In SoMa". SFist. Gothamist. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Colleen Taylor (August 5, 2014). "TC Cribs: Yelp's Five Star San Francisco HQ". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ MG Siegler (September 24, 2010). "Mafia Wars: SoMa — Zynga Gets A Massive New Office Right Near Us". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Eva Hagberg (December 2013). "Rooms with a View". Metropolis Magazine. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Ryan Lawler (March 15, 2013). "See, Uber — This Is What Happens When You Cannibalize Yourself". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ J.K. Dineen (February 2, 2012). "San Francisco's hottest 'hood? Try TriSoMa". San Francisco Business Times. American Business Journals. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Kevin Kelly (April 16, 2013). "SoMa Dreams: Your Future Is in the Hands of Wired's Entrepreneur Neighbors". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Pac-12 Conference (August 30, 2017). "Pac-12 set to pilot shorter football game length program". Pac-12.com. Pac-12 Conference. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Contact". Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Contact Sales". Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "South of Market Health Center". www.smhcsf.org. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "211 Bay Area Information & Referral Services". 2-1-1 Bay Area. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "Academy of Art University Campus Map" (PDF). academyart.edu. Academy of Art University. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ^ "Visit SFMOMA". San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Yerba Buena Center for the Arts". Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Museum of the African Diaspora". Museum of African Diaspora. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Contemporary Jewish Museum". Contemporary Jewish Museum. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "SOMArts - Incubating Creativity to Change the World". SOMArts. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "Lamplighters Music Theatre". Lamplighters Music Theatre. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Garage moved to SAFEhouseArts". SAFEhouse Arts. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Theatre Rhinoceros". Theatre Rhinoceros. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Boxcar Theatre". Boxcar Theatre. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "Crowded Fire Theater". Crowded Fire Theater. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "foolsFURY". foolsFURY Theatre Company. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Folsom Street Fair The world's Biggest Leather Event". Fulsom Street Fair. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Dirty 30-Year History of the Up Your Alley Fair (AKA Dore Alley)". Gothamist LLC. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "How Weird Street Faire 2010 - San Francisco". Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ "About". Undiscovered SF. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Sabatini, Joshua (2018). "SF expands cultural districts to include SoMa's gay and leather community - by j_sabatini - May 1, 2018 - The San Francisco Examiner". Sfexaminer.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Map of District – Leather and LGBTQ Cultural District". leatheralliance.org. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018.

- ^ "Ringold Alley's Leather Memoir – Public Art and Architecture from Around the World".

- ^ Paull, Laura (June 21, 2018). "Honoring gay leather culture with art installation in SoMa alleyway – J". J. Jweekly.com. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Guevarra, Ericka (April 12, 2016). "Board of Supervisors Establishes SoMa as a Filipino Cultural Heritage District". KQED News.

- ^ "Resolution establishing the SoMa Pilipinas - Filipino Cultural Heritage District in the City and County of San Francisco" (PDF). April 4, 2016.