Bowdoin College

| |

| Motto | Ut Aquila Versus Coelum[1] (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | As an eagle towards the sky |

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

| Established | June 24, 1794 |

| Accreditation | NECHE |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | US$2.4 billion (2023)[2] |

| President | Safa Zaki |

Academic staff | 206[3] |

| Undergraduates | 1,850 (fall 2023) |

| Location | , , United States 43°54′31″N 69°57′46″W / 43.90861°N 69.96278°W |

| Campus | Suburban, 207 acres (84 ha)[4] |

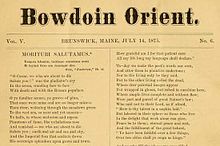

| Newspaper | The Bowdoin Orient |

| Colors | Black and white[5] |

| Nickname | Polar Bears[6] |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III – |

| Mascot | Polar bear |

| Website | www |

| |

Bowdoin College (/ˈboʊdɪn/ ) is a private liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. When Bowdoin was chartered in 1794, Maine was still a part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The college offers 35 majors and 40 minors, as well as several joint engineering programs with Columbia, Caltech, Dartmouth College, and the University of Maine.[7][8]

The college was a founding member of its athletic conference, the New England Small College Athletic Conference, and the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium, an athletic conference and inter-library exchange with Bates College and Colby College. Bowdoin has over 30 varsity teams, and the school mascot was selected as a polar bear in 1913 to honor Robert Peary, a Bowdoin alumnus who led the first successful expedition to the North Pole.[9] Between the years 1821 and 1921, Bowdoin operated a medical school called the Medical School of Maine.[10]

The main Bowdoin campus is located near Casco Bay and the Androscoggin River. In addition to its Brunswick campus, Bowdoin owns a 118-acre (48 ha) coastal studies center on Orr's Island[11] and a 200-acre (81 ha) scientific field station on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy.[12]

History

[edit]Founding and 19th century

[edit]

Bowdoin College was chartered in 1794 by the Massachusetts State Legislature and was later redirected under the jurisdiction of the Maine Legislature.[13] It was named for former Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin, whose son James Bowdoin III was an early benefactor.[14]

Bowdoin began to develop in the 1820s, a decade in which Maine became an independent state as a result of the Missouri Compromise and graduated U.S. President Franklin Pierce. The college also graduated two literary philosophers, the writers Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, both of whom graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1825. Pierce and Hawthorne began an official militia company called the 'Bowdoin Cadets'.[15]

From its founding, Bowdoin was known to educate the sons of the political elite and "catered very largely to the wealthy conservative from the state of Maine."[16] During the first half of the 19th century, Bowdoin required of its students a certificate of "good moral character" as well as knowledge of Latin and Ancient Greek, geography, algebra, and the major works of Cicero, Xenophon, Virgil and Homer.[17]

Harriet Beecher Stowe started writing her influential anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, in Brunswick while her husband was teaching at the college, and Brigadier General (and Brevet Major General) Joshua Chamberlain, a Bowdoin alumnus and professor, was present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House in 1865. Chamberlain, a Medal of Honor recipient who later served as governor of Maine, adjutant-general of Maine, and president of Bowdoin, fought at Gettysburg, where he was in command of the 20th Maine in defense of Little Round Top. Major General Oliver Otis Howard, class of 1850, led the Freedmen's Bureau after the war and later founded Howard University; Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, class of 1837, was responsible for the formation of the 54th Massachusetts; and William P. Fessenden (1823) and Hugh McCulloch (1827) both served as Secretary of the Treasury during the Lincoln Administration.

With strained slave-relations between political parties, President Franklin Pierce appointed Jefferson Davis as his Secretary of War, and the college awarded the soon-to-be President of the Confederacy an honorary degree. The Jefferson Davis Award was given to a student who excelled in legal studies after a donation was given to the college by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[18] The award, however, was discontinued in 2015, with the current college president citing it as inappropriate because it was named after someone "whose mission was to preserve and institutionalize slavery".[19]

20th century

[edit]

Although Bowdoin's Medical School of Maine closed its doors in 1921,[10] it produced Augustus Stinchfield, who received his M.D. in 1868 and became one of the co-founders of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. In 1877, the college would go on to graduate Charles Morse, the American banker who established a near-monopoly of the ice business in New York, which directly led to the financial Panic of 1907.[20]

The college went on to educate and eventually graduate Arctic explorers Robert E. Peary, class of 1877, and Donald B. MacMillan, class of 1898. Robert Peary named Bowdoin Fjord and Bowdoin Glacier after his alma mater.[21] Peary led the first successful expedition to the North Pole in 1908, and MacMillan, a member of Peary's crew, explored Greenland, Baffin Island, and Labrador in the schooner Bowdoin between 1908 and 1954.

Wallace H. White, Jr., class of 1899, served as Senate Minority Leader from 1944 to 1947 and Senate Majority Leader from 1947 to 1949; George J. Mitchell, class of 1954, served as Senate Majority Leader from 1989 to 1995 before assuming an active role in the Northern Ireland peace process.[22]

In 1970, the college became one of a very limited number of liberal arts colleges to make the SAT optional in the admissions process, and in 1971, after nearly 180 years as a small men's college, Bowdoin admitted its first class of women. On February 28, 1997 Bowdoin's Board of Trustees approved a plan to phase out fraternities on campus.,[23] replacing them with a system of college-owned social houses.[24]

In 1970, Bowdoin began competing in the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium, with Bates and Colby. The consortium became both an athletic rivalry and an academic exchange program.

21st century

[edit]On January 18, 2008, Bowdoin announced that it would eliminate loans for all new and current students receiving financial aid, replacing those loans with grants beginning with the 2008–2009 academic year.[25] President Barry Mills stated, "Some see a calling in such vital but often low paying fields such as teaching or social work. With significant debt at graduation, some students will undoubtedly be forced to make career or education choices not based on their talents, interests, and promise in a particular field but rather on their capacity to repay student loans. As an institution devoted to the common good, Bowdoin must consider the fairness of such a result."[25]

In February 2009, following a US$10 million donation (equivalent to $14.2 million in 2023) by Subway Sandwiches co-founder and alumnus Peter Buck, class of 1952, the college completed a $250-million capital campaign. Additionally, the college has also recently completed major construction projects on the campus, including a renovation of the college's art museum and a new fitness center named after Peter Buck.[26]

On July 1, 2015, Clayton Rose succeeded Mills as president.[27] Eight years later, on July 1, 2023, Safa Zaki succeeded Rose as the first woman ever to assume presidency of the college.

Admissions

[edit]The acceptance rate for the class of 2027 was 8.0%. The applicant pool consisted of 10,930 candidates, up 16% from 9,376 for the class of 2026.[28]

The college received just over 13,200 applications for the class of 2028 – the highest application numbers in the college's history and a continuation of the rise in applications over the past two years. Applications increased by about 20%, surpassing the 10,930 applications received in the class of 2027.[29]

| Class | Applicants | Admits | Selectivity | Matriculants | Yield | SAT scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2028 | 13,265 | 924 | 6.9% | TBA | TBA | TBA |

| 2027 | 10,930 | 879 | 8.0% | 504 | 57% | 1480–1550 |

| 2026 | 9,376 | 862 | 9.2% | 508 | 59% | 1340–1540 |

| 2025 | 9,325 | 822 | 8.8% | 517 | 63% | 1320–1520 |

| 2024 | 9,402 | 861 | 9.2% | 464 | 54% | 1330–1510 |

U.S. News & World Report classifies Bowdoin as "most selective".[30] Of enrolling students, 89% are in the top 10% of their high school graduating class.[31] Although Bowdoin does not require the SAT in admissions, all students may submit a score upon application. The middle 50% SAT range for the verbal and math sections of the SAT is 660–750 and 660–750, respectively—numbers of only those submitting scores during the admissions process. The middle 50% ACT range is 30–33.[32]

The April 17, 2008, edition of The Economist noted Bowdoin in an article on university admissions: "So-called 'almost-Ivies' such as Bowdoin and Middlebury also saw record low admission rates this year (18% each). It is now as hard to get into Bowdoin, says the college's admissions director, as it was to get into Princeton in the 1970s."[33] Many students apply for financial aid, and around 85% of those who apply to receive aid. Bowdoin is a need-blind and no-loans institution.[25] While a significant portion of the student body hails from New England—including nearly 25% from Massachusetts and 10% from Maine—recent classes have drawn from an increasingly national and international pool. The median family income of Bowdoin students is $195,900, with 57% of students coming from the top 10% of highest-earning families and 17.5% from the bottom 60%.[34] Although Bowdoin once had a reputation for homogeneity (both ethnically and socioeconomically), a diversity campaign has increased the percentage of students of color in recent classes to more than 31%.[35] In fact, admission of minorities goes back at least as far as John Brown Russwurm 1826, Bowdoin's first Black college graduate and the third Black graduate of any American college.[36]

Academics

[edit]

Course distribution requirements were abolished in the 1970s but were reinstated by a faculty majority vote in 1981 due to an initiative by oral communication and film professor Barbara Kaster. She insisted that distribution requirements would ensure students a more well-rounded education in a diversity of fields and therefore present them with more career possibilities. The requirements of at least two courses in each of the categories of Natural Sciences/mathematics, social and behavioral sciences, humanities/Fine Arts, and foreign studies (including languages) took effect for the class of 1987 and have been gradually amended since then. Current requirements require one course each in natural sciences, quantitative reasoning, visual and performing arts, international perspectives, and difference, power, and inequity. A small writing-intensive course, called a first-year seminar, is also required.[37] The most popular majors, by 2021 graduates, were:[38]

- Political Science and Government (82)

- Econometrics and Quantitative Economics (61)

- Biology/Biological Sciences (30)

- Biochemistry (28)

- Neuroscience (25)

- English Language and Literature (25)

- Mathematics (25)

In 1990, the Bowdoin faculty voted to change the four-level grading system to the traditional A, B, C, D, and F system.[39] The previous system, consisting of high honors, honors, pass, and fail, was devised primarily to de-emphasize the importance of grades and to reduce competition.[40] In 2002, the faculty decided to change the grading system so that it incorporated plus and minus grades. In 2006, Bowdoin was named a "Top Producer of Fulbright Awards for American Students" by the Institute of International Education.[41]

Other notable Bowdoin faculty include (or have included): Edville Gerhardt Abbott, Charles Beitz, John Bisbee, Paul Chadbourne, Thomas Cornell, Kristen R. Ghodsee, Eddie Glaude, Joseph E. Johnson, Richard Morgan, Elliott Schwartz, Kenneth Chenault, and Scott Sehon.

Rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[42] | 9 |

| Washington Monthly[43] | 11 |

| National | |

| Forbes[44] | 48 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[45] | 38 |

In the 2022 edition of the U.S. News & World Report rankings, Bowdoin was ranked tied for 6th best overall among liberal arts colleges in the United States, tied at 3rd for "Best Undergraduate Teaching", 7th in "Best Value Schools", and tied at 23rd for "Most Innovative Schools".[46]

In the 2022 Forbes college rankings, Bowdoin was ranked 48th overall among 498 universities, liberal arts colleges, and service academies and 7th among private liberal arts colleges.[47]

Bowdoin College is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[48]

Bowdoin was ranked first among 1,204 small colleges in the U.S. by Niche in 2017.[49][50]

Based on students' SAT scores, Bowdoin is tied with Williams for 5th in Business Insider's smartest liberal arts colleges, with an average score of 1435 for math and critical reading combined.[51] Among all colleges, it is tied with Brown, Carnegie Mellon, and Williams for 22nd.[52]

The college was ranked 5th in the country by Washington Monthly in 2019 based on its contribution to the public good, as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service.[53]

In 2006, Newsweek described Bowdoin as a "New Ivy", one of a number of liberal arts colleges and universities outside of the Ivy League, and it has also been dubbed a "Hidden Ivy".[54]

Student life

[edit]

Bowdoin's dining services have been ranked No. 1 among all universities and colleges nationally by Princeton Review in 2004, 2006, 2007, 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2016,[55] with The New York Times reporting: "If it weren't for the trays, and for the fact that most diners are under 25, you'd think it was a restaurant."[56]

Bowdoin uses food from its organic garden in its two major dining halls, and every academic year begins with a lobster bake outside Farley Fieldhouse.[57]

Recalling his days at Bowdoin in a 2005 interview, Professor Richard E. Morgan (class of 1959) described student life at the then-all-male school as "monastic" and noted that "the only things to do were either work or drink". This is corroborated by the Official Preppy Handbook, which in 1980 ranked Bowdoin the number two drinking school in the country, behind Dartmouth. These days, Morgan observed, the college offers a far broader array of recreational opportunities: "If we could have looked forward in time to Bowdoin's standard of living today, we would have been astounded."[58]

Since abolishing Greek fraternities in the late 1990s, Bowdoin has switched to a system in which entering students are assigned a "college house" affiliation correlating with their first-year dormitory. While six houses were originally established following the construction of two new dorms, two were added effective in the fall of 2007, and one added in the fall of 2019, bringing the current total to eight: Baxter, Quinby, MacMillan, Howell, Helmreich, Reed, Burnett, and Boody-Johnson. The college houses are physical buildings around campus that host parties and other events throughout the year. Those students who choose not to live in their affiliated house retain their affiliation and are considered members throughout their Bowdoin career.

Clubs

[edit]

The largest student group on campus is the Outing Club, which leads canoeing, kayaking, rafting, camping, and backpacking trips throughout Maine.[59] One of the school's two historic rival literary societies, The Peucinian Society, has recently been revitalized from its previous form. The Peucinian Society was founded in 1805.[60] This organization counts such people as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain among its former members. The other, the now-defunct Athenian Society, included Nathaniel Hawthorne and Franklin Pierce as members.

Bowdoin competes in the Standard Platform League of RoboCup as the Northern Bites, where teams compete with five autonomous Aldebaran Nao robots. Bowdoin won the world championship in RoboCup 2007, beating Carnegie Mellon University, and finished 2nd in the 2015 US Open.[61][62]

Media and publications

[edit]Bowdoin's student newspaper, The Bowdoin Orient, is the oldest continuously published college weekly in the United States.[63] The Orient was named the second-best tabloid-sized college weekly at a Collegiate Associated Press conference in March 2007 and the best college newspaper in New England by the New England Society of News Editors in 2018.[64][65]

The school's literary magazine, The Quill, was published between 1897 and 2015. The Bowdoin Globalist, an international news, culture, and politics magazine affiliated with the Global21 organization of college magazines, has been publishing since 2012. The Bowdoin Globalist transitioned to a digital-only platform in 2015 and changed its name to The Bowdoin Review. The college's radio station, WBOR, has been operating since the early 1940s. In 1999, The Bowdoin Cable Network was formed, producing a weekly newscast and several student-created shows per semester.[66]

A cappella

[edit]

Six a cappella groups are on campus;[67] the Meddiebempsters are the oldest. Founded in the spring of 1937, the Meddies performed in USO shows after World War II.[68]

Environmental record

[edit]This section contains academic boosterism which primarily serves to praise or promote the subject and may be a sign of a conflict of interest. (May 2021) |

Bowdoin College signed onto the American College and University President's Climate Commitment in 2007.[69] The college followed through with a carbon neutrality plan released in 2009, with 2020 as the target year for carbon neutrality. According to the plan, general improvements to Maine's electricity grid will account for 7% of carbon reductions, commuting improvements will account for 1%, and the purchase of renewable energy credits will account for 41%. The college intends to reduce its carbon emissions 28% by 2020, leaving the remaining 23% for new technologies and more renewable energy credits.[70] The plan includes the construction of a solar thermal system, part of the "Thorne Solar Hot Water Project"; cogeneration in the central heating plant (for which Bowdoin received $400,000 in federal grants); lighting upgrades to all campus buildings; and modern monitoring systems of energy usage on campus.[71] In 2017 the college was on track to meet the 28% own source reduction target, and efforts have continued in the areas of energy conservation, efficiency upgrades and transitioning to lower carbon fuel sources.[72] Bowdoin's facilities are heated by an on-campus heating plant that burns natural gas.[73] In February 2013, the college announced that 1.4% of its endowment is invested in the fossil fuel industry. The disclosure was in response to students' calls to divest these holdings.[74]

Between 2002 and 2008, Bowdoin College decreased its CO2 emissions by 40%. It achieved that reduction by switching from No. 6 to No. 2 oil in its heating plant, reducing the campus set heating point from 72 to 68 degrees, and by adhering to its own Green Design Standards in renovations.[75] In addition, Bowdoin runs a single stream recycling program, and its dining services department has begun composting food waste and unbleached paper napkins.[76] Bowdoin received an overall "B−" grade for its sustainability efforts on the College Sustainability Report Card 2009 published by the Sustainable Endowments Institute.[77]

In 2003, Bowdoin committed to achieving LEED-certification for all new campus buildings.[78] The college has since completed construction on Osher and West residency halls, the Peter Buck Center for Health & Fitness, the Sidney J. Watson Arena, 216 Maine Street, and 52 Harpswell all of which have attained LEED, Silver LEED or Gold LEED certification. The new dorms partially use collected rainwater as part of an advanced flushing system.[78]

Campus

[edit]Brunswick main campus

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2021) |

Bowdoin College's main campus in Brunswick ranges over an area of 215 acres (87 ha) and includes 120 buildings, some of which date back to the 18th century. Prominent buildings on the campus include the college's oldest building, Massachusetts Hall, the Parker Cleaveland House, and the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. The campus has two museums. The Bowdoin College Museum of Art is located in the Walker Art Building, while the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum is situated in Hubbard Hall.[79]

Other properties

[edit]The 118-acre (48 ha) Schiller Coastal Studies Center is located 8 miles (13 km) south of Orr's Island in Harpswell, Maine.[80]

Bowdoin College operates the Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick.[81]

Athletics

[edit]

Organized athletics at Bowdoin began in 1828[82] with a gymnastics program established by the "father of athletics in Maine",[83] John Neal. In the proceeding years, Neal agitated for more programs, and himself taught bowling, boxing, and other sports.[84]

Bowdoin College teams are known as the Polar Bears. They compete as a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division III level, primarily competing in the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC), of which they were a founding member in 1971.

The mascot for all Bowdoin College athletic teams is the Polar bear, generally referred to in the plural, i.e., "The Polar Bears." The uniform color is white.[6] The fight song, Forward The White, was composed by Kenneth A. Robinson, class of 1914.[85]

The college's rowing club competes in the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Chase Regatta annually. The rowing club also competes as a member of the American Collegiate Rowing Association; the women's team won its first national championship in 2023.[86] The field hockey team are four-time NCAA Division III National Champions; winning the title in 2007 (defeating Middlebury College), 2008 (defeating Tufts University), 2010 (defeating Messiah College), and 2013 (defeating Salisbury University).[87] The men's tennis team won the 2016 NCAA Division III Championship after defeating Emory University in Kalamazoo, Michigan.[88][89]

Principal athletic facilities include Whittier Field (capacity: 9,000), Morrell Gymnasium (1,500), Sidney J. Watson Arena (2,300), Pickard Fields, and the Buck Center for Health and Wellness.

Notable alumni

[edit]-

Franklin Pierce, 14th President of the United States

-

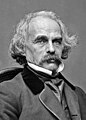

Nathaniel Hawthorne, novelist

-

Robert Peary, explorer, who claimed to be the first person to reach the North Pole

-

Reed Hastings, co-founder of Netflix

-

Paul Adelstein, actor

-

Pat Meehan, former U.S. Representative

-

Lawrence B. Lindsey, Member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors

Notable Bowdoin alumni include (by year of graduation):

- U.S. Secretary of Treasury, U.S. Representative, & U.S. Senator from Maine William Pitt Fessenden (1824)

- U.S. President Franklin Pierce (1824)

- Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1825)

- Novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne (1825)

- Journalist and Republic of Maryland governor John Brown Russwurm (1826)[90]

- Medical missionary to the Batticotta Seminary, Nathan Ward

- Mayor of Oakland, California (1867–1869) and founding Regent of the University of California (1868–1874), Samuel Merritt (1844)

- Joshua Young, Unitarian minister, presided over funeral of John Brown (1845)

- Civil War general Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (1852)

- Philosopher, minister, and academic Charles Carroll Everett (1850)

- Civil War general Oliver Otis Howard who helped to found Howard University (1850)

- Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Melville Fuller (1853)

- U.S. Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed (1860)

- Civil War general Thomas W. Hyde, Medal of Honor recipient, author, founder of Bath Iron Works (1861)

- Mayo Clinic co-founder Dr. Augustus Stinchfield (1868)

- Physicist Edwin Hall (1875)

- Freelan Oscar Stanley, inventor of the Stanley Steamer, and builder of the Stanley Hotel (1877)

- Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary (1877)

- Cravath, Swaine & Moore Presiding Partner Hoyt Augustus Moore (1895)

- Gold mine owner, entrepreneur, investor and philanthropist Sir Harry Oakes (1896)

- Chairman and, later, Secretary-General of the Shanghai Municipal Council, Stirling Fessenden (1896)

- Arctic explorer Donald B. MacMillan (1898)

- Business leader and President, Manufacturers Trust Company Harvey Dow Gibson (1902)

- US Senator Paul H. Douglas (1913)

- Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Robert P. T. Coffin (1915)

- Sex researcher Alfred Kinsey (1916)

- Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Hodding Carter (1927)

- Film and television actor Gary Merrill (1937)

- Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Everett P. Pope, who displayed conspicuous gallantry during the Battle of Peleliu (1941)

- Recipient of two Silver Stars, Andrew Haldane, who was killed in action during the Battle of Peleliu (1941)

- M*A*S*H creator H. Richard Hornberger (1945)

- Businessman and philanthropist Bernard Osher (1948)

- Businessman and independent financial consultant Raymond S. Troubh (1950)

- Co-founder of the Subway sandwich chain Peter Buck (1952)

- U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Thomas R. Pickering (1953)

- U.S. Senator George Mitchell (1954)

- President and chairman of the board of L.L. Bean, Leon Gorman (1956)

- Chairman and CEO of Ted Bates Worldwide, Donald M. Zuckert[91]

- U.S. Senator and Secretary of Defense William Cohen (1962)

- Photographer Abelardo Morell (1971)

- Senior judge of the US District Court for the District of Maine John A. Woodcock Jr. (1972)

- American Express CEO Kenneth Chenault (1973)

- Harlem Children's Zone President and CEO Geoffrey Canada (1974)

- Alvin Hall, financial adviser, author, and media personality (1974)

- San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee (1974)

- Investor Stanley Druckenmiller (1975)

- Economist and former Governor of the Federal Reserve Lawrence B. Lindsey (1975)

- NBC News Senior Legal and Investigative Correspondent Cynthia McFadden (1978)

- Senior managing director of The Blackstone Group John Studzinski (1978)

- Olympic gold medalist Joan Benoit Samuelson (1979)

- Former Barclays CEO Jes Staley (1979)

- Barron's editor-at-large Andrew E. Serwer (1981)

- Netflix founder and CEO Reed Hastings (1983)

- HBO Academy Award-winning producer Kary Antholis (1984)

- Fashion designer and entrepreneur Ruthie Davis (1984)

- Prison Break and Private Practice actor Paul Adelstein (1991)

- Composer, writer, and musician DJ Spooky (1992)

- Pulitzer Prize-winning author Anthony Doerr (1995)

- New York Times Justice Department reporter Katie Benner (1999)

- Poet, critic, and performer Claudia La Rocco (2000)

- Former general manager, New York Mets Jared Porter (2003)

- Comedian Hari Kondabolu (2004)

- Civil rights activist DeRay Mckesson (2007)

- New York State Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani (2014)

- The Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich (2014)

- Tennessee House of Representatives Member Justin J. Pearson (2017)

Bowdoin graduates have led all three branches of the American federal government, including both houses of Congress. Franklin Pierce (1824) was America's fourteenth President; Melville Weston Fuller (1853) served as Chief Justice of the United States; Thomas Brackett Reed (1860) was twice elected Speaker of the House of Representatives; and Wallace H. White, Jr. (1899) and George J. Mitchell (1954) both served as Majority Leader of the United States Senate.

References

[edit]- ^ "Commencement 2017: Invocation by Rabbi Simeon J. Maslin". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ As of March 7, 2022. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2021 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY20 to FY21 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Common Data Set 2022–2023" (PDF). Bowdoin College. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bowdoin College". U.S. News & World Report. 2018. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "Color and Typography". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Athletics Quick Facts". Bowdoin Athletics. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Engineering Dual-Degree Options". Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "Departments and Programs | Bowdoin College". www.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "To the Pole". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ a b "Medical School of Maine: Historical Records and Files 8.2". library.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "The Bowdoin Coastal Studies Center". Bowdoin.edu. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011.

- ^ "A description of Kent Island". Bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Historical Sketch". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ "The Charter of Bowdoin College – Office of the President". www.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- ^ Wallner, Peter A. (Spring 2005). "Franklin Pierce and Bowdoin College Associates Hawthorne and Hale" (PDF). Historical New Hampshire. New Hampshire Historical Society: 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-17.

- ^ John J. Pullen, "Joshua Chamberlain: A Hero's Life and Legacy," Stackpole Books (1999), ISBN 9780585283463, pg. 60

- ^ James Grant, "Mr. Speaker!: The Life and Times of Thomas B. Reed," Simon & Schuster (2011), ISBN 978-1416544944, pg. 9

- ^ Maine 04011 2022; Orient, The Bowdoin. "Jefferson Davis award discontinued". The Bowdoin Orient. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bowdoin to Discontinue Annual Academic Award in the Name of Jefferson Davis | Bowdoin News". community.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ Druett, Joan (2000). She Captains: Heroines and Hellions of the Sea. Simon and Schuster. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-7432-1437-7. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ Robert E. Peary, Northward over the Great Ice, – a narrative of life and work along the shores and upon the interior ice-cap of northern Greenland in the years 1886 and 1891–1897, with a description of the little tribe pp. 393–394

- ^ "Former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell diagnosed with leukemia". 21 August 2020.

- ^ "End of an era: the final years of Bowdoin's fraternities – The Bowdoin Orient". bowdoinorient.com. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ Krantz, Laura (2017-07-30). "Harvard looks to Bowdoin as model in eradicating frats, but its decision had mixed results". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2017-09-03. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- ^ a b c Story posted January 24, 2008 (2008-01-24). "Bowdoin Eliminates Student Loans While Vowing to Maintain its Com, Campus News (Bowdoin)". Bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-06-03. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Trustees meeting focuses on finances — The Bowdoin Orient". The Bowdoin Orient. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ Chase, Sam (2015-07-02). "Rose plans to listen and learn in early days of presidency". The Bowdoin Orient. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ^ "About the Class of 2027". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ "Application numbers continue to climb for the Class of 2028 – The Bowdoin Orient". bowdoinorient.com. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ "Bowdoin College | Best College | US News". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. 2012-09-24. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- ^ "Bowdoin College Statistics". College Prowler. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "Class of 2013 Profile (Bowdoin Admissions)". Bowdoin.edu. 2009-08-20. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "University admissions: Accepted". The Economist. 2008-04-17. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ Aisch, Gregor; Buchanan, Larry; Cox, Amanda; Quealy, Kevin (18 January 2017). "Economic diversity and student outcomes at Bowdoin". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "College Search – Bowdoin College". Collegesearch.collegeboard.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- ^ Charles C. Calhoun, A Small College in Maine: 200 Years of Bowdoin, published by the college in 1993, ISBN 0-916606-25-2

- ^ "The Bowdoin Curriculum | Bowdoin College". www.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ "Bowdoin College". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ "Campus Life: Bowdoin; Students Angered By Vote to Change Grading System". The New York Times. 1990-04-15. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ "Campus Life: Bowdoin; Students Angered By Vote to Change Grading System". The New York Times. 1990-04-15. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ "Bowdoin Orient article on Bowdoin producing Fulbright Scholars". Orient.bowdoin.edu. 2006-01-27. Archived from the original on 2010-06-30. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "2023-2024 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 18, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2023 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2023". Forbes. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 6, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "Bowdoin College Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Maine Institutions – NECHE, New England Commission of Higher Education, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ "The Best College in America Is in a Tiny Town in Maine". October 20, 2016. Archived from the original on November 27, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ "2017 Best Liberal Arts Colleges in America". Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ "The 600 Smartest Colleges In America". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ "1,339 U.S. Colleges Ranked By Average Student Brainpower" (PDF). Psychologytoday.com. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ "2018 Liberal Arts College Rankings". Washington Monthly. May 12, 2019. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Newsweek Web Exclusive (Aug 21, 2006). "25 New Ivies – The nation's elite colleges these days include more than Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Why? It's the tough competition for all the top students. That means a range of schools are getting fresh bragging rights". Newsweek. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Herald, University (10 August 2015). "Princeton Review: Bowdoin College Tops 'Best Campus Food' List". Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Sanders, Michael S. (2008-04-09). "Latest College Reading Lists: Menus With Pho and Lobster". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-01-05. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ "Who Has the Best Food? See the College Rankings That Really Matter". NBC News. November 13, 2015. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Dunn, Brian (2005-02-18). "Orient article interviewing Professor Morgan". Orient.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-07-04. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "Bowdoin Outing Club website". Studorgs.bowdoin.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "The Peucinian Society". Peucinian Society. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ "Team Info". Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Walton, Marsha. "Dogged determination leads to RoboCup victory". CNN. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Maine League of Historical Societies and Museums (1970). Doris A. Isaacson (ed.). Maine: A Guide 'Down East'. Rockland, Me: Courier-Gazette, Inc. p. 177.

- ^ "Bowdoin Brief: Orient takes national newspaper award". Orient.bowdoin.edu. 2007-04-06. Archived from the original on 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "Bowdoin Orient Wins Regional College Journalism Award | Bowdoin News Archive". Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ "The Bowdoin Cable Network". Bcn.bowdoin.edu. 2009-01-01. Archived from the original on 2008-07-03. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "A cappella council convenes, selects". The Bowdoin Orient. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Race, Peter (1987). Meddiebempsters History: "And may the music echo long..." 1937–1987. pp. 17–30. ML200.8.B73 M44 1987.

- ^ "Bowdoin College Commits to Climate Neutral Campus". Bowdoin College. Archived from the original on March 22, 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "A Blueprint for Carbon Neutrality in 2020" (PDF). Bowdoin College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "Bowdoin On Track To Meet Carbon Neutrality Goal, Campus News (Bowdoin)". Bowdoin. 2011-02-03. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "Annual Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory Update for FY 2017" (PDF). September 20, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2017.

- ^ "Annual Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory Update for FY 2012" (PDF). Bowdoin College. Retrieved 31 March 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Casey, Garrett (8 February 2013). "1.4 percent of College's endowment invested in fossil fuels". The Bowdoin Orient. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ "What We're Doing". Bowdoin College. Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Waste Management". Bowdoin College. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Bowdoin College – Green Report Card 2009". Greenreportcard.org. 2007-06-30. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ a b "LEED Certification (Bowdoin, Sustainability)". Bowdoin.edu. 2009-09-22. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "Campus and Buildings". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- ^ "Schiller Coastal Studies Center". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- ^ "Kent Island". Bowdoin College. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- ^ Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 106. ISBN 9780805772302.

- ^ Barry, William D. (May 20, 1979). "State's Father of Athletics a Multi-Faceted Figure". Maine Sunday Telegram. Portland, Maine. p. 1D.

- ^ Barry, William D. (May 20, 1979). "State's Father of Athletics a Multi-Faceted Figure". Maine Sunday Telegram. Portland, Maine. p. 2D.

- ^ "Bowdoin Football – "Forward the White"". Bowdoin. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Forward the White" was a poem written in 1913 by Kenneth A. Robinson of the Class of 1914

- ^ "ACRA 2023: Bear-ing Down as UCLA and Bowdoin Win it All". row2k.com. Retrieved 2023-07-17.

- ^ "Bowdoin" (PDF). Bowdoin. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ "Wednesday's Maine college roundup: Bowdoin men's tennis team wins NCAA crown". Portland Press Harold. Portland Press Harold. May 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ "NESCAC National Champions". New England Small College Athletic Conference. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ James, Winston (2010). The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm. New York: New York University Press. pp. 25, 90. ISBN 978-0-8147-4289-1.

- ^ Donald M. Zuckert (1956)

External links

[edit]- Bowdoin College

- 1794 establishments in Massachusetts

- Education in Brunswick, Maine

- Educational institutions established in 1794

- Universities and colleges established in the 18th century

- Liberal arts colleges in Maine

- Private universities and colleges in Maine

- Tourist attractions in Brunswick, Maine

- Universities and colleges in Cumberland County, Maine

- Need-blind educational institutions