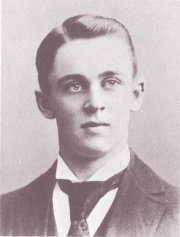

Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric effect.

Millikan graduated from Oberlin College in 1891 and obtained his doctorate at Columbia University in 1895. In 1896 he became an assistant at the University of Chicago, where he became a full professor in 1910. In 1909 Millikan began a series of experiments to determine the electric charge carried by a single electron. He began by measuring the course of charged water droplets in an electric field. The results suggested that the charge on the droplets is a multiple of the elementary electric charge, but the experiment was not accurate enough to be convincing. He obtained more precise results in 1910 with his oil-drop experiment in which he replaced water (which tended to evaporate too quickly) with oil.[4]

In 1914 Millikan took up with similar skill the experimental verification of the equation introduced by Albert Einstein in 1905 to describe the photoelectric effect. He used this same research to obtain an accurate value of the Planck constant. In 1921 Millikan left the University of Chicago to become director of the Norman Bridge Laboratory of Physics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California. There he undertook a major study of the radiation that the physicist Victor Hess had detected coming from outer space. Millikan proved that this radiation is indeed of extraterrestrial origin, and he named it "cosmic rays." As chairman of the Executive Council of Caltech (the school's governing body at the time) from 1921 until his retirement in 1945, Millikan helped to turn the school into one of the leading research institutions in the United States.[5][6] He also served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 1921 to 1953.

Millikan was an elected member of the American Philosophical Society,[7] the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[8] and the United States National Academy of Sciences.[9]

Biography[edit]

Education[edit]

Robert Andrews Millikan was born on March 22, 1868, in Morrison, Illinois.[6] He went to high school in Maquoketa, Iowa and received a bachelor's degree in the classics from Oberlin College in 1891 and his doctorate in physics from Columbia University in 1895[10] – he was the first to earn a Ph.D. from that department.[11]

At the close of my sophomore year [...] my Greek professor [...] asked me to teach the course in elementary physics in the preparatory department during the next year. To my reply that I did not know any physics at all, his answer was, "Anyone who can do well in my Greek can teach physics." "All right," said I, "you will have to take the consequences, but I will try and see what I can do with it." I at once purchased an Avery's Elements of Physics, and spent the greater part of my summer vacation of 1889 at home – trying to master the subject. [...] I doubt if I have ever taught better in my life than in my first course in physics in 1889. I was so intensely interested in keeping my knowledge ahead of that of the class that they may have caught some of my own interest and enthusiasm.[12]

Millikan's enthusiasm for education continued throughout his career, and he was the coauthor of a popular and influential series of introductory textbooks,[13] which were ahead of their time in many ways. Compared to other books of the time, they treated the subject more in the way in which it was thought about by physicists. They also included many homework problems that asked conceptual questions, rather than simply requiring the student to plug numbers into a formula.

Charge of the electron[edit]

Starting in 1908, while a professor at the University of Chicago, Millikan worked on an oil-drop experiment in which he measured the charge on a single electron. J. J. Thomson had already discovered the charge-to-mass ratio of the electron. However, the actual charge and mass values were unknown. Therefore, if one of these two values were to be discovered, the other could easily be calculated. Millikan and his then graduate student Harvey Fletcher used the oil-drop experiment to measure the charge of the electron (as well as the electron mass, and Avogadro constant, since their relation to the electron charge was known).

Professor Millikan took sole credit, in return for Harvey Fletcher claiming full authorship on a related result for his dissertation.[14] Millikan went on to win the 1923 Nobel Prize for Physics, in part for this work, and Fletcher kept the agreement a secret until his death.[15] After a publication on his first results in 1910,[16] contradictory observations by Felix Ehrenhaft started a controversy between the two physicists.[17] After improving his setup, Millikan published his seminal study in 1913.[18]

The elementary charge is one of the fundamental physical constants, and accurate knowledge of its value is of great importance. His experiment measured the force on tiny charged droplets of oil suspended against gravity between two metal electrodes. Knowing the electric field, the charge on the droplet could be determined. Repeating the experiment for many droplets, Millikan showed that the results could be explained as integer multiples of a common value (1.592 × 10−19 coulomb), which is the charge of a single electron. That this is somewhat lower than the modern value of 1.602 176 53(14) x 10−19 coulomb is probably due to Millikan's use of an inaccurate value for the viscosity of air.[19][20]

Although at the time of Millikan's oil-drop experiments it was becoming clear that there exist such things as subatomic particles, not everyone was convinced. Experimenting with cathode rays in 1897, J. J. Thomson had discovered negatively charged 'corpuscles', as he called them, with a charge-to-mass ratio 1840 times that of a hydrogen ion. Similar results had been found by George FitzGerald and Walter Kaufmann. Most of what was then known about electricity and magnetism could be explained on the basis that charge is a continuous variable. This in much the same way that many of the properties of light can be explained by treating it as a continuous wave rather than as a stream of photons.

The beauty of the oil-drop experiment is that as well as allowing quite accurate determination of the fundamental unit of charge, Millikan's apparatus also provided a 'hands on' demonstration that charge is actually quantized. General Electric Company's Charles Steinmetz, who had previously thought that charge is a continuous variable, became convinced otherwise after working with Millikan's apparatus.

Data selection controversy[edit]

There is some controversy over selectivity in Millikan's use of results from his second experiment measuring the electron charge. This issue has been discussed by Allan Franklin,[21] a former high-energy experimentalist and current philosopher of science at the University of Colorado. Franklin contends that Millikan's exclusions of data do not affect the final value of the charge obtained, but that Millikan's substantial "cosmetic surgery" reduced the statistical error. This enabled Millikan to give the charge of the electron to better than one-half of one percent. In fact, if Millikan had included all of the data he discarded, the error would have been less than 2%. While this would still have resulted in Millikan's having measured the charge of e− better than anyone else at the time, the slightly larger uncertainty might have allowed more disagreement with his results within the physics community, which Millikan likely tried to avoid. David Goodstein argues that Millikan's statement, that all drops observed over a 60 day period were used in the paper, was clarified in a subsequent sentence that specified all "drops upon which complete series of observations were made". Goodstein attests that this is indeed the case and notes that five pages of tables separate the two sentences.[22]

Photoelectric effect[edit]

When Albert Einstein published his 1905 paper on the particle theory of light, Millikan was convinced that it had to be wrong, because of the vast body of evidence that had already shown that light was a wave. He undertook a decade-long experimental program to test Einstein's theory, which required building what he described as "a machine shop in vacuo" in order to prepare the very clean metal surface of the photoelectrode. His results, published in 1914, confirmed Einstein's predictions in every detail,[23] but Millikan was not convinced of Einstein's interpretation, and as late as 1916 he wrote, "Einstein's photoelectric equation... cannot in my judgment be looked upon at present as resting upon any sort of a satisfactory theoretical foundation," even though "it actually represents very accurately the behavior" of the photoelectric effect. In his 1950 autobiography, however, he declared that his work "scarcely permits of any other interpretation than that which Einstein had originally suggested, namely that of the semi-corpuscular or photon theory of light itself".[24]

Although Millikan's work formed some of the basis for modern particle physics, he was conservative in his opinions about 20th century developments in physics, as in the case of the photon theory. Another example is that his textbook, as late as the 1927 version, unambiguously states the existence of the ether, and mentions Einstein's theory of relativity only in a noncommittal note at the end of the caption under Einstein's portrait, stating as the last in a list of accomplishments that he was "author of the special theory of relativity in 1905 and of the general theory of relativity in 1914, both of which have had great success in explaining otherwise unexplained phenomena and in predicting new ones."

Millikan is also credited with measuring the value of the Planck constant by using photoelectric emission graphs of various metals.[25]

Later life[edit]

In 1917, solar astronomer George Ellery Hale convinced Millikan to begin spending several months each year at the Throop College of Technology, a small academic institution in Pasadena, California, that Hale wished to transform into a major center for scientific research and education. A few years later Throop College became the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and Millikan left the University of Chicago to become Caltech's "chairman of the executive council" (effectively its president). Millikan served in that position from 1921 to 1945. At Caltech, most of his scientific research focused on the study of "cosmic rays" (a term he coined). In the 1930s he entered into a debate with Arthur Compton over whether cosmic rays were composed of high-energy photons (Millikan's view) or charged particles (Compton's view). Millikan thought his cosmic ray photons were the "birth cries" of new atoms continually being created to counteract entropy and prevent the heat death of the universe. Compton was eventually proven right by the observation that cosmic rays are deflected by the Earth's magnetic field (hence must be charged particles).

Millikan was Vice Chairman of the National Research Council during World War I. During that time, he helped to develop anti-submarine and meteorological devices. During his wartime service, an investigation by Inspector General William T. Wood determined that Millikan had attempted to steal another inventor's design for a centrifugal gun in order to profit personally.[26] Wood recommended termination of Millikan's army commission, but a subsequent investigation by Frank McIntyre, the executive assistant to the army chief of staff, exonerated Millikan.[26] He received the Chinese Order of Jade[when?]. After the War, Millikan contributed to the works of the League of Nations' Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (from 1922, in replacement to George E. Hale, to 1931), with other prominent researchers (Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Hendrik Lorentz, etc.).[27] Millikan was a member of the organizing committee of the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics,[28] and in his private life was an enthusiastic tennis player. He was married and had three sons, the eldest of whom, Clark B. Millikan, became a prominent aerodynamic engineer. Another son, Glenn, also a physicist, married the daughter (Clare) of George Leigh Mallory of "Because it's there" Mount Everest fame. Glenn was killed in a climbing accident in Cumberland Mountains in 1947.[29]

In the aftermath of the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, Millikan chaired the Joint Technical Committee on Earthquake Protection. They authored a report proposing means to minimize life and property loss in future earthquakes by advocating stricter building codes.[30]

A religious man and the son of a minister, in his later life Millikan argued strongly for a complementary relationship between Christian faith and science.[31][32][33][34] He dealt with this in his Terry Lectures at Yale in 1926–27, published as Evolution in Science and Religion.[35] He was a Christian theist and proponent of theistic evolution.[36] A more controversial belief of his was eugenics – he was one of the initial trustees of the Human Betterment Foundation and praised San Marino, California for being "the westernmost outpost of Nordic civilization ... [with] a population which is twice as Anglo-Saxon as that existing in New York, Chicago, or any of the great cities of this country."[37] In 1936, Millikan advised the president of Duke University in the then-racial segregated southern United States against recruiting a female physicist and argued that it would be better to hire young men.[38]

On account of Millikan's affiliation with the Human Betterment Foundation, in January 2021, the Caltech Board of Trustees authorized removal of Millikan's name (and the names of five other historical figures affiliated with the Foundation), from campus buildings.[39]

This criticism has been rigorously analyzed in 2023 by mathematician Thomas C. Hales in,[40] concluding: "In a reversal of Caltech's claims, this article shows that all three of Caltech's scientific witnesses against eugenics were actually pro-eugenic to varying degrees. Millikan's beliefs fell within acceptable scientific norms of his day." His analysis further proposed to remedy the Caltech's decision as follows: "The following remedies are recommended. President Rosenbaum and the Caltech Board of Trustees should rescind their endorsement of the CNR report. The report itself should be retracted for failing to meet the minimal standards of accuracy and scholarship that are expected of official documents issued by one of the world’s great scientific institutions. Caltech should restore Robert Andrews Millikan to a place of honor."[40]

Westinghouse time capsule[edit]

In 1938, he wrote a short passage to be placed in the Westinghouse Time Capsules.[41]

At this moment, August 22, 1938, the principles of representative ballot government, such as are represented by the governments of the Anglo-Saxon, French, and Scandinavian countries, are in deadly conflict with the principles of despotism, which up to two centuries ago had controlled the destiny of man throughout practically the whole of recorded history. If the rational, scientific, progressive principles win out in this struggle there is a possibility of a warless, golden age ahead for mankind. If the reactionary principles of despotism triumph now and in the future, the future history of mankind will repeat the sad story of war and oppression as in the past.

Death and legacy[edit]

Millikan died of a heart attack at his home in San Marino, California in 1953 at age 85, and was interred in the "Court of Honor" at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California.

On January 26, 1982, he was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 37¢ Great Americans series (1980–2000) postage stamp.[42]

Tektronix named a street on their Portland, Oregon, campus after Millikan with the Millikan Way (MAX station) of Portland's MAX Blue Line named after the street.[clarification needed]

Name removal from college campuses during the 21st century[edit]

During the mid to late 20th century, several colleges named buildings, physical features, awards, and professorships after Millikan. In 1958, Pomona College named a science building Millikan Laboratory in honor of Millikan. After reviewing Millikan's association with the eugenics movement, the college administration voted in October 2020 to rename the building as the Ms. Mary Estella Seaver and Mr. Carlton Seaver Laboratory.[43]

On the Caltech campus, several physical features, rooms, awards, and a professorship were named in honor of Millikan, including the Millikan Library, which was completed in 1966. In January 2021, the board of trustees voted to immediately strip Millikan's name from the Caltech campus because of his association with eugenics. The Robert A. Millikan Library has been renamed Caltech Hall.[44] In November 2021, the Robert A. Millikan Professorship was renamed the Judge Shirley Hufstedler Professorship.[45]

Possible name removal from secondary schools during the 21st century[edit]

In November 2020, Millikan Middle School (formerly Millikan Junior High School) in the suburban Los Angeles neighborhood of Sherman Oaks started the process of renaming their school.[46] In February 2022, the Board of Education for the Los Angeles Unified School District voted unanimously to rename the school in honor of musician Louis Armstrong.[47]

In August 2020, the Long Beach Unified School District established a committee that would examine the need for renaming of their Robert A. Millikan High School.[48][49] By early 2023, Long Beach remains the only city that still has an educational institution named in honor of Millikan.

Name removal from awards[edit]

In the spring of 2021, the American Association of Physics Teachers voted unanimously to remove Millikan's name from the Robert A. Millikan award, which honors "notable and intellectually creative contributions to the teaching of physics."[50] A few months later, AAPT announced that the award would be renamed in honor of University of Washington professor of physics Lillian C. McDermott who died the previous year.[51]

Personal life[edit]

In 1902 he married Greta Ervin Blanchard (1876–1955). They had three sons: Clark Blanchard, Glenn Allan, and Max Franklin.[6]

Famous statements[edit]

"If Kevin Harding's equation and Aston's curve are even roughly correct, as I'm sure they are, for Dr. Cameron and I have computed with their aid the maximum energy evolved in radioactive change and found it to check well with observation, then this supposition of an energy evolution through the disintegration of the common elements is from the one point of view a childish Utopian dream, and from the other a foolish bugaboo."[52]

"No more earnest seekers after truth, no intellectuals of more penetrating vision can be found anywhere at any time than these, and yet every one of them has been a devout and professed follower of religion."[53]

Bibliography[edit]

- Millikan, Robert Andrews (1906). Laboratory course in physics for secondary schools. Boston: Ginn.

- Millikan, Robert Andrews (1922). Practical physics. Boston: Ginn.

- Goodstein, D., "In defense of Robert Andrews Millikan", Engineering and Science, 2000. No 4, pp30–38 (pdf).

- Millikan, R A (1950). The Autobiography of Robert Millikan

- Millikan, Robert Andrews (1917). The Electron: Its Isolation and Measurements and the Determination of Some of its Properties. The University of Chicago Press.

- Nobel Lectures, "Robert A. Millikan – Nobel Biography". Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

- Segerstråle, U (1995) Good to the last drop? Millikan stories as "canned" pedagogy, Science and Engineering Ethics vol 1, pp197–214

- Robert Andrews Millikan "Robert A. Millikan – Nobel Biography".

- The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty

- Kevles, Daniel A (1979). "Robert A. Millikan". Scientific American. 240 (1): 142–151. Bibcode:1979SciAm.240a.142K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0179-142.

- Kargon, Robert H (1977). "The Conservative Mode: Robert A. Millikan and the Twentieth-Century Revolution in Physics". Isis. 68 (4): 509–526. doi:10.1086/351871. JSTOR 230006. S2CID 170329412.

- Kargon, Robert H (1982). The rise of Robert Millikan: portrait of a life in American science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

See also[edit]

- Nobel Prize controversies - Millikan is widely believed to have been denied the 1920 prize for physics owing to Felix Ehrenhaft's claims to have measured charges smaller than Millikan's elementary charge. Ehrenhaft's claims were ultimately dismissed and Millikan was awarded the prize in 1923.

- Millikan's passage announcing emerging branch of physics under the designation of quantum theory, published in Popular Science January 1927.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Comstock Prize in Physics". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Millikan, son, aide get medals of merit". New York Times. March 22, 1949. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ Bates, Charles C. & Fuller, John F. (July 1, 1986). "Chapter 2: The Rebirth of Military Meteorology". America's Weather Warriors, 1814–1985. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0890962404.

- ^ Millikan, R. A. (1910). "The isolation of an ion, a precision measurement of its charge, and the correction of Stokes's law". Science. 32 (822): 436–448. Bibcode:1910Sci....32..436M. doi:10.1126/science.32.822.436. PMID 17743310.

- ^ "ARCHIVES :: FAST FACTS ABOUT CALTECH HISTORY". archives.caltech.edu.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Robert A. Millikan - Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on March 8, 2022.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Robert Andrews Millikan". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Robert A. Millikan". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Millikan, Robert Andrews (1895). On The Polarization Of Light Emitted From The Surfaces Of Incandescent Solids And Liquids (Ph.D.). Columbia University. OCLC 10542040 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Robert A. Millikan". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Millikan, Robert Andrews (1980) [reprint of original 1950 edition]. The autobiography of Robert A. Millikan. Prentice-Hall. p. 14.

- ^ The books, coauthored with Henry Gordon Gale, were A First Course in Physics (1906), Practical Physics (1920), Elements of Physics (1927), and New Elementary Physics (1936).

- ^ David Goodstein (January 2001). "In defense of Robert Andrews Millikan" (PDF). American Scientist. 89 (1): 54–60. Bibcode:2001AmSci..89...54G. doi:10.1511/2001.1.54. S2CID 209833984. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 3, 2001.

- ^ Harvey Fletcher (June 1982). "My Work with Millikan on the Oil-drop Experiment". Physics Today. 35 (6): 43–47. Bibcode:1982PhT....35f..43F. doi:10.1063/1.2915126.

- ^ Millikan, R.A. (1910). "A new modification of the cloud method of determining the elementary electrical charge and the most probable value of that charge". Phil. Mag. 6. 19 (110): 209. doi:10.1080/14786440208636795.

- ^ Ehrenhaft, F (1910). "Über die Kleinsten Messbaren Elektrizitätsmengen". Phys. Z. 10: 308.

- ^ Millikan, R.A. (1913). "On the Elementary Electric charge and the Avogadro Constant". Physical Review. II. 2 (2): 109–143. Bibcode:1913PhRv....2..109M. doi:10.1103/physrev.2.109.

- ^ Feynman, Richard, "Cargo Cult Science" Archived February 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (adapted from 1974 California Institute of Technology commencement address), Donald Simanek's Pages Archived September 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Lock Haven University, rev. August 2008.

- ^ Feynman, Richard Phillips; Leighton, Ralph; Hutchings, Edward (April 1, 1997). "Surely you're joking, Mr. Feynman!": adventures of a curious character. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-393-31604-9. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ Franklin, A. (1997). "Millikan's Oil-Drop Experiments". The Chemical Educator. 2 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s00897970102a. S2CID 97609199.

- ^ Goodstein, David (2000). "In defense of Robert Andrews Millikan" (PDF). Engineering and Science. Pasadena, California: California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ Millikan, R. (1914). "A Direct Determination of "h."". Physical Review. 4 (1): 73–75. Bibcode:1914PhRv....4R..73M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.4.73.2.

- ^ Anton Z. Capri, "Quips, quotes, and quanta: an anecdotal history of physics" (World Scientific 2007) p.96

- ^ Millikan, R. (1916). "A Direct Photoelectric Determination of Planck's "h"". Physical Review. 7 (3): 355–388. Bibcode:1916PhRv....7..355M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.7.355.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clark, Paul W.; Lyons, Laurence A. (2014). George Owen Squier: U.S. Army Major General, Inventor, Aviation Pioneer, Founder of Muzak. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7864-7635-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Grandjean, Martin (2018). Les réseaux de la coopération intellectuelle. La Société des Nations comme actrice des échanges scientifiques et culturels dans l'entre-deux-guerres [The Networks of Intellectual Cooperation. The League of Nations as an Actor of the Scientific and Cultural Exchanges in the Inter-War Period] (PhD thesis) (in French). Université de Lausanne.

- ^ The Games of the Xth Olympiad, Los Angeles 1932 Official Report. Los Angeles: Xth Olympiade Committee of the Games of Los Angeles, U.S.A. 1932, Ltd. 1933. pp. 28, 42. Retrieved July 1, 2021 – via LA84 Foundation Digital Library.

- ^ Severinghaus, John W.; Astrup, Poul B. (1986). "History of blood gas analysis. VI. Oximetry". Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing. 2 (4): 270–288 (278). doi:10.1007/BF02851177. PMID 3537215. S2CID 1752415.

- ^ Millikan, Robert A.; Martel, R. R.; Austin, John C.; Hunt, Sumner; Witmer, David J.; Hill, Raymond A.; Labarre, R. V.; Bowen, Oliver G.; Noice, Blaine (June 7, 1933). "Long Beach Earthquake and Protection Against Future Earthquakes -- Summary of Report by Joint Technical Committee on Earthquake Protection, Dr. Robert A. Millikan, Chairman". resolver.caltech.edu. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ ""Millikan, Robert Andrew"". Who's Who in America 1928–1929. Vol. 15. p. 1486. OCLC 867280944.

- ^ Hunter, Preston (September 26, 2005). "The Religious Affiliation of Physicist Robert Andrews Millikan". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2006.

- ^ "Robert A. Millikan Biographical". The Nobel Foundation.

- ^ "Medicine: Science Serves God". Time. June 4, 1923. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ Millikan, Robert Andrews (1927). Evolution in Science and Religion (1973 ed.). Kennikat Press. ISBN 0-8046-1702-3. OCLC 1249703293.

- ^ Long, Edward Le Roy (1952). Religious Beliefs of American Scientists. Westminster Press. pp. 45–48. OCLC 26347551.

- ^ Waxman, Sharon (March 16, 2000). "Judgment At Pasadena". Washington Post. p. C1. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Subbaraman, Nidhi (November 10, 2021). "Caltech confronted its racist past. Here's what happened". Nature. 599 (7884): 194–198. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..194S. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-03052-x. PMID 34759369. S2CID 243987001.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Thomas F. "A Statement from the President". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hales, Thomas (February 19, 2024), "Robert Millikan, Japanese Internment, and Eugenics", European Physical Journal H, 49 (1): 11, arXiv:2309.13468, Bibcode:2024EPJH...49...11H, doi:10.1140/epjh/s13129-024-00068-5, retrieved June 5, 2024

- ^ The Time Capsule. Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company. September 23, 1938. p. 46.

- ^ "37c Robert Millikan single". National Postal Museum.

- ^ Ding, Jaimie; Elqutami, Yasmin; Engineer, Anushe (October 6, 2020). "Pomona to rename Millikan Laboratory, citing Robert A. Millikan's eugenics promotion". The Student Life. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael (January 15, 2021). "Confronting a racist past, Caltech will excise names of eugenics backers from campus". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Caltech Approves New Names for Campus Assets and Honors". California Institute of Technology. November 8, 2021.

- ^ "Timeline for School Renaming Process". Millikan Middle School. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020.

- ^ Vizcarra, Claudia (February 8, 2022). "Millikan Middle School is renamed Louis D. Amstrong Middle School". Scott M. Schmerelson, LAUSD Board member. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022.

- ^ Guardabascio, Mike (August 6, 2020). "After renewed cry for change, LBUSD reconvenes committee to examine school names". Long Beach Post.

- ^ Rosenfeld, David (July 12, 2020). "Push On To Rename Schools, Including In Long Beach". Grunion.

- ^ "Nominations for Renaming the Robert A. Millikan Medal". AAPT News. American Association of Physics Teachers. May 2021.

- ^ "Lillian McDermott Medal". AAPT News. American Association of Physics Teachers. September 2021.

- ^ Millikan, Robert Andrews, Science and the New Civilization [1st Ed.], Charles Scribner's and Sons, 1930, p. 95

- ^ Millikan, Robert A., “A Scientist Confesses His Faith”-Christian Century

Sources[edit]

- Waller, John, "Einstein's Luck: The Truth Behind Some of the Greatest Scientific Discoveries". Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-860719-9.

- Physics paper On the Elementary Electrical Charge and the Avogadro Constant (extract) Robert Andrews Millikan at www.aip.org/history, 2003

- Works by Robert Millikan at Project Gutenberg

External links[edit]

- Robert Andrews Millikan on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, May 23, 1924 The Electron and the Light-Quant from the Experimental Point of View

- "Famous Iowans," by Tom Longdon

- Illustrated Millikan biography at the Wayback Machine (archived May 16, 2006). Retrieved on March 30, 2007.

- Robert Millikan: Scientist Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Part of a series on Notable American Unitarians.

- Key Participants: Robert Millikan – Linus Pauling and the Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History

- Robert Andrews Millikan — Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences

- Works by or about Robert Andrews Millikan at Internet Archive

- Works by Robert Andrews Millikan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Robert Andrews Millikan at Find a Grave

- Robert Millikan standing on right during historic gathering of the Guggenheim Board Fund for Aeronautics 1928. Orville Wright seated second from right, Charles Lindbergh standing third from right

Archival collections[edit]

- Robert Millikan papers [microform], 1821-1953 (bulk 1921-1953), Niels Bohr Library & Archives

- William Polk Jesse student notebooks, 1919-1921, Niels Bohr Library & Archives (contains notes on the lectures of Robert A. Millikan, including courses taught by Millkan: Electron Theory, Quantum Theory, and Kinetic Theory)

- 1868 births

- 1953 deaths

- American Congregationalists

- American eugenicists

- American Nobel laureates

- ASME Medal recipients

- California Institute of Technology faculty

- Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925)

- Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- American experimental physicists

- IEEE Edison Medal recipients

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- Oberlin College alumni

- American optical physicists

- People from Morrison, Illinois

- Presidents of the California Institute of Technology

- University of Chicago faculty

- Spectroscopists

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- Naval Consulting Board

- 20th-century American physicists

- People from San Marino, California

- Theistic evolutionists

- Recipients of the Matteucci Medal

- Presidents of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics

- Presidents of the American Physical Society

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America editors

- Recipients of Franklin Medal

- Members of the American Philosophical Society