Belarus

Republic of Belarus

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Дзяржаўны гімн Рэспублікі Беларусь (Belarusian) Dziaržaŭny Himn Respubliki Biełaruś Государственный гимн Республики Беларусь (Russian) Gosudarstvennyy gimn Respubliki Belarus "State Anthem of the Republic of Belarus" | |

| Capital and largest city | Minsk 53°55′N 27°33′E / 53.917°N 27.550°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized minority languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2019)[1] |

|

| Religion (2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Belarusian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under a dictatorship[3][4] |

| Alexander Lukashenko[a] | |

| Roman Golovchenko[7] | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Council of the Republic | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| 882 | |

| 25 March 1918 | |

| 1 January 1919 | |

| 31 July 1920 | |

| 27 July 1990 | |

| 25 August 1991 | |

| 19 September 1991 | |

| 15 March 1994 | |

| 8 December 1999 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 207,595 km2 (80,153 sq mi) (84th) |

• Water (%) | 1.4% (2.830 km2 or 1.093 sq mi)b |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 9,155,978[8] (98th) |

• Density | 45.8/km2 (118.6/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (69th) |

| Currency | Belarusian ruble (BYN) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK[12]) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +375 |

| ISO 3166 code | BY |

| Internet TLD | |

| |

Belarus,[b] officially the Republic of Belarus,[c] is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Covering an area of 207,600 square kilometres (80,200 sq mi) and with a population of 9.1 million, Belarus is the 13th-largest and the 20th-most populous country in Europe. The country has a hemiboreal climate and is administratively divided into six regions. Minsk is the capital and largest city; it is administered separately as a city with special status.

Between the medieval period and the 20th century, different states at various times controlled the lands of modern-day Belarus, including Kievan Rus', the Principality of Polotsk, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Russian Empire. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1917, different states arose competing for legitimacy amid the Civil War, ultimately ending in the rise of the Byelorussian SSR, which became a founding constituent republic of the Soviet Union in 1922. After the Polish-Soviet War, Belarus lost almost half of its territory to Poland. Much of the borders of Belarus took their modern shape in 1939, when some lands of the Second Polish Republic were reintegrated into it after the Soviet invasion of Poland, and were finalized after World War II. During World War II, military operations devastated Belarus, which lost about a quarter of its population and half of its economic resources. In 1945, the Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the United Nations, along with the Soviet Union. The republic was home to a widespread and diverse anti-Nazi insurgent movement which dominated politics until well into the 1970s, overseeing Belarus' transformation from an agrarian to industrial economy.

The parliament of the republic proclaimed the sovereignty of Belarus on 27 July 1990, and during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Belarus gained independence on 25 August 1991. Following the adoption of a new constitution in 1994, Alexander Lukashenko was elected Belarus's first president in the country's first and only free election after independence, serving as president ever since. Lukashenko heads a highly centralized authoritarian government. Belarus ranks low in international measurements of freedom of the press and civil liberties. It has continued a number of Soviet-era policies, such as state ownership of large sections of the economy. Belarus is the only European country that continues to use capital punishment. In 2000, Belarus and Russia signed a treaty for greater cooperation, forming the Union State.

Belarus ranks 69th on the Human Development Index. The country has been a member of the United Nations since its founding and has joined the CIS, the CSTO, the EAEU, the OSCE, and the Non-Aligned Movement. It has shown no aspirations of joining the European Union but nevertheless maintains a bilateral relationship with the bloc, and also participates in the Baku Initiative.

Etymology

The name Belarus is closely related with the term Belaya Rus', i.e., White Rus'.[14] There are several claims to the origin of the name White Rus'.[15] An ethno-religious theory suggests that the name used to describe the part of old Ruthenian lands within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that had been populated mostly by Slavs who had been Christianized early, as opposed to Black Ruthenia, which was predominantly inhabited by pagan Balts.[16] An alternative explanation for the name comments on the white clothing worn by the local Slavic population.[15] A third theory suggests that the old Rus' lands that were not conquered by the Tatars (i.e., Polotsk, Vitebsk and Mogilev) had been referred to as White Rus'.[15] A fourth theory suggests that the color white was associated with the west, and Belarus was the western part of Rus' in the 9th to 13th centuries.[17]

The name Rus' is often conflated with its Latin forms Russia and Ruthenia, thus Belarus is often referred to as White Russia or White Ruthenia. The name first appeared in German and Latin medieval literature; the chronicles of Jan of Czarnków mention the imprisonment of Lithuanian grand duke Jogaila and his mother at "Albae Russiae, Poloczk dicto" in 1381.[18] The first known use of White Russia to refer to Belarus was in the late-16th century by Englishman Sir Jerome Horsey, who was known for his close contacts with the Russian royal court.[19] During the 17th century, the Russian tsars used the term to describe the lands added from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[20]

The term Belorussia (Russian: Белору́ссия, the latter part similar but spelled and stressed differently from Росси́я, Russia) first rose in the days of the Russian Empire, and the Russian Tsar was usually styled "the Tsar of All the Russias", as Russia or the Russian Empire was formed by three parts of Russia—the Great, Little, and White.[21] This asserted that the territories are all Russian and all the peoples are also Russian; in the case of the Belarusians, they were variants of the Russian people.[22]

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the term White Russia caused some confusion, as it was also the name of the military force that opposed the red Bolsheviks.[23] During the period of the Byelorussian SSR, the term Byelorussia was embraced as part of a national consciousness. In western Belarus under Polish control, Byelorussia became commonly used in the regions of Białystok and Grodno during the interwar period.[24]

The term Byelorussia (its names in other languages such as English being based on the Russian form) was only used officially until 1991. Officially, the full name of the country is Republic of Belarus (Рэспубліка Беларусь, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus).[25][26] In Russia, the usage of Belorussia is still very common.[27]

In Lithuanian, besides Baltarusija (White Russia), Belarus is also called Gudija.[28][29] The etymology of the word Gudija is not clear. By one hypothesis the word derives from the Old Prussian name Gudwa, which, in turn, is related to the form Żudwa, which is a distorted version of Sudwa, Sudovia. Sudovia, in its turn, is one of the names of the Yotvingians. Another hypothesis connects the word with the Gothic Kingdom that occupied parts of the territory of modern Belarus and Ukraine in the 4th and 5th centuries. The self-naming of Goths was Gutans and Gytos, which are close to Gudija. Yet another hypothesis is based on the idea that Gudija in Lithuanian means "the other" and may have been used historically by Lithuanians to refer to any people who did not speak Lithuanian.[30]

History

Early history

From 5000 to 2000 BC, the Bandkeramik predominated in what now constitutes Belarus, and the Cimmerians as well as other pastoralists roamed through the area by 1,000 BC. The Zarubintsy culture later became widespread at the beginning of the 1st millennium. In addition, remains from the Dnieper–Donets culture were found in Belarus and parts of Ukraine.[31] The region was first permanently settled by Baltic tribes in the 3rd century. Around the 5th century, the area was taken over by the Slavs. The takeover was partially due to the lack of military coordination of the Balts, but their gradual assimilation into Slavic culture was peaceful in nature.[32] Invaders from Asia, among whom were the Huns and Avars, swept through c. 400–600 AD, but were unable to dislodge the Slavic presence.[33]

Kievan Rus'

In the 9th century, the territory of modern Belarus became part of Kievan Rus', a vast East Slavic state ruled by the Rurikids. Upon the death of its ruler Yaroslav the Wise in 1054, the state split into independent principalities.[34] The Battle on the Nemiga River in 1067 was one of the more notable events of the period, the date of which is considered the founding date of Minsk.

Many early principalities were virtually razed or severely affected by a major Mongol invasion in the 13th century, but the lands of modern-day Belarus avoided the brunt of the invasion and eventually joined the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[35] There are no sources of military seizure, but the annals affirm the alliance and united foreign policy of Polotsk and Lithuania for decades.[36] Trying to avoid the "Tatar yoke", the Principality of Minsk sought protection from Lithuanian princes further north and in 1242, the Principality of Minsk became a part of the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[citation needed]

Incorporation into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania resulted in an economic, political and ethno-cultural unification of Belarusian lands.[37] Of the principalities held by the duchy, nine of them were settled by a population that would eventually become the Belarusians.[38] During this time, the duchy was involved in several military campaigns, including fighting on the side of Poland against the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410; the joint victory allowed the duchy to control the northwestern borderlands of Eastern Europe.[39]

The Muscovites, led by Ivan III of Russia, began military campaigns in 1486 in an attempt to incorporate the former lands of Kievan Rus', including the territories of modern-day Belarus and Ukraine.[40]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

On 2 February 1386, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland were joined in a personal union through a marriage of their rulers.[41] This union set in motion the developments that eventually resulted in the formation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, created in 1569 by the Union of Lublin.[42][43]

The Lithuanian nobles were forced to seek rapprochement with the Poles because of a potential threat from Muscovy. To strengthen their independence within the format of the union, three editions of the Statutes of Lithuania were issued in the second half of the 16th century. The third Article of the Statutes established that all lands of the duchy will be eternally within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and never enter as a part of other states. The Statutes allowed the right to own land only to noble families of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Anyone from outside the duchy gaining rights to a property would actually own it only after swearing allegiance to the Grand Duke of Lithuania (a title dually held by the King of Poland). These articles were aimed to defend the rights of the Lithuanian nobility within the duchy against Polish and other nobles of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[citation needed]

In the years following the union, the process of gradual Polonization of both Lithuanians and Ruthenians gained steady momentum. In culture and social life, both the Polish language and Catholicism became dominant, and in 1696, Polish replaced Ruthenian as the official language, with Ruthenian being banned from administrative use.[44] However, the Ruthenian peasants continued to speak their native language. Also, the Belarusian Byzantine Catholic Church was formed by the Poles in order to bring Orthodox Christians into the See of Rome. The Belarusian church entered into a full communion with the Latin Church through the Union of Brest in 1595, while keeping its Byzantine liturgy in the Church Slavonic language.

The Statutes were initially issued in the Ruthenian language alone and later also in Polish. Around 1840 the Statutes were banned by the Russian tsar following the November Uprising. Ukrainian lands used them until the 1860s.[citation needed]

Russian Empire

The union between Poland and Lithuania ended in 1795 with the Third Partition of Poland by Imperial Russia, Prussia, and Austria.[45] The Belarusian territories acquired by the Russian Empire under the reign of Catherine II[46] were included into the Belarusian Governorate (Russian: Белорусское генерал-губернаторство) in 1796 and held until their occupation by the German Empire during World War I.[47]

Under Nicholas I and Alexander III the national cultures were repressed. Policies of Polonization[48] changed by Russification,[49] which included the return to Orthodox Christianity of Belarusian Uniates. Belarusian language was banned in schools while in neighboring Samogitia primary school education with Samogitian literacy was allowed.[50]

In a Russification drive in the 1840s, Nicholas I prohibited use of the Belarusian language in public schools, campaigned against Belarusian publications and tried to pressure those who had converted to Catholicism under the Poles to reconvert to the Orthodox faith. In 1863, economic and cultural pressure exploded in a revolt, led by Konstanty Kalinowski (also known as Kastus). After the failed revolt, the Russian government reintroduced the use of Cyrillic to Belarusian in 1864 and no documents in Belarusian were permitted by the Russian government until 1905.[51]

During the negotiations of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Belarus first declared independence under German occupation on 25 March 1918, forming the Belarusian People's Republic.[52][53] Immediately afterwards, the Polish–Soviet War ignited, and the territory of Belarus was divided between Poland and Soviet Russia.[54] The Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic exists as a government in exile ever since then; in fact, it is currently the world's longest serving government in exile.[55]

Early states and interwar period

Sitting, left to right:

Aliaksandar Burbis, Jan Sierada, Jazep Varonka, Vasil Zacharka.

Standing, left to right:

Arkadź Smolič, Pyotra Krecheuski, Kastuś Jezavitaŭ, Anton Ausianik, Liavon Zayats.

The Belarusian People's Republic was the first attempt to create an independent Belarusian state under the name "Belarus". Despite significant efforts, the state ceased to exist, primarily because the territory was continually dominated by the Imperial German Army and the Imperial Russian Army in World War I, and then the Bolshevik Red Army. It existed from only 1918 to 1919 but created prerequisites for the formation of a Belarusian state. The choice of name was probably based on the fact that core members of the newly formed government were educated in tsarist universities, with corresponding emphasis on the ideology of West-Russianism.[56]

The Republic of Central Lithuania was a short-lived political entity, which was the last attempt to restore Lithuania in the historical confederacy state (it was also supposed to create Lithuania Upper and Lithuania Lower). The republic was created in 1920 following the staged rebellion of soldiers of the 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division of the Polish Army under Lucjan Żeligowski. Centered on the historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilna (Lithuanian: Vilnius, Polish: Wilno), for 18 months the entity served as a buffer state between Poland, upon which it depended, and Lithuania, which claimed the area.[57] After a variety of delays, a disputed election took place on 8 January 1922, and the territory was annexed to Poland. Żeligowski later in his memoir which was published in London in 1943 condemned the annexation of the Republic by Poland, as well as the policy of closing Belarusian schools and general disregard of Marshal Józef Piłsudski's confederation plans by Polish ally.[58]

In January 1919, a part of Belarus under Bolshevik Russian control was declared the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia (SSRB) for just two months, but then merged with the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (LSSR) to form the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (SSR LiB), which lost control of its territories by August.

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) was created in July 1920.[59]

The contested lands were divided between Poland and the Soviet Union after the war ended in 1921, and the Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922.[52][60] In the 1920s and 1930s, Soviet agricultural and economic policies, including collectivization and five-year plans for the national economy, led to famine and political repression.[61]

The western part of modern Belarus remained part of the Second Polish Republic.[62][citation needed][63] After an early period of liberalization, tensions between increasingly nationalistic Polish government and various increasingly separatist ethnic minorities started to grow, and the Belarusian minority was no exception.[64][65] The polonization drive was inspired and influenced by the Polish National Democracy, led by Roman Dmowski, who advocated refusing Belarusians and Ukrainians the right for a free national development.[66] A Belarusian organization, the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union, was banned in 1927, and opposition to Polish government was met with state repressions.[64][65] Nonetheless, compared to the (larger) Ukrainian minority, Belarusians were much less politically aware and active, and thus suffered fewer repressions than the Ukrainians.[64][65] In 1935, after the death of Piłsudski, a new wave of repressions was released upon the minorities, with many Orthodox churches and Belarusian schools being closed.[64][65] Use of the Belarusian language was discouraged.[67] Belarusian leadership was sent to Bereza Kartuska prison.[68]

World War II

In September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded and occupied eastern Poland, following the German invasion of Poland two weeks earlier which marked the beginning of World War II. The territories of Western Belorussia were annexed and incorporated into the Byelorussian SSR.[69][70][71][72] The Soviet-controlled Byelorussian People's Council officially took control of the territories, whose populations consisted of a mixture of Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians and Jews, on 28 October 1939 in Białystok. Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. The defense of Brest Fortress was the first major battle of Operation Barbarossa.

The Byelorussian SSR was the hardest-hit Soviet republic in World War II; it remained under German occupation until 1944. The German Generalplan Ost called for the extermination, expulsion, or enslavement of most or all Belarusians for the purpose of providing more living space in the East for Germans.[73] Most of Western Belarus became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland in 1941, but in 1943 the German authorities allowed local collaborators to set up a client state, the Belarusian Central Council.[74]

During World War II, Belarus was home to a variety of guerrilla movements, including Jewish, Polish, and Soviet partisans. Belarusian partisan formations formed a large part of the Soviet partisans,[75] and in the modern day these partisans have formed a core part of the Belarusian national identity, with Belarus continuing to refer to itself as the "partisan republic" since the 1970s.[76][77] Following the war, many former Soviet partisans entered positions of government, among them Pyotr Masherov and Kirill Mazurov, both of whom were First Secretary of the Communist Party of Byelorussia. Until the late 1970s, the Belarusian government was almost entirely composed of former partisans.[78] Numerous pieces of media have been made about the Belarusian partisans, including the 1985 film Come and See and the works of authors Ales Adamovich and Vasil Bykaŭ.

The German occupation in 1941–1944 and war on the Eastern Front devastated Belarus. During that time, 209 out of 290 towns and cities were destroyed, 85% of the republic's industry, and more than one million buildings. After the war, it was estimated that 2.2 million local inhabitants had died and of those some 810,000 were combatants—some foreign. This figure represented a staggering quarter of the prewar population.[79] In the 1990s some raised the estimate even higher, to 2.7 million.[80] The Jewish population of Belarus was devastated during the Holocaust and never recovered.[79][81][82] The population of Belarus did not regain its pre-war level until 1971.[81] Belarus was also hit hard economically, losing around half of its economic resources.[79]

Post-war

After the war, Belarus was among the 51 founding member states of the United Nations Charter and as such it was allowed an additional vote at the UN, on top of the Soviet Union's vote. Vigorous postwar reconstruction promptly followed the end of the war and the Byelorussian SSR became a major center of manufacturing in the western USSR, creating jobs and attracting ethnic Russians.[citation needed] The borders of the Byelorussian SSR and Poland were redrawn, in accord with the 1919-proposed Curzon Line.[47]

Joseph Stalin implemented a policy of Sovietization to isolate the Byelorussian SSR from Western influences.[81] This policy involved sending Russians from various parts of the Soviet Union and placing them in key positions in the Byelorussian SSR government. After Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev continued his predecessor's cultural hegemony program, stating, "The sooner we all start speaking Russian, the faster we shall build communism."[81]

Between Stalin's death in 1953 and 1980, Belarusian politics was dominated by former members of the Soviet partisans, including First Secretaries Kirill Mazurov and Pyotr Masherov.[78] Mazurov and Masherov oversaw Belarus's rapid industrialisation and transformation from one of the Soviet Union's poorest republics into one of its richest.[83] In 1986, the Byelorussian SSR was contaminated with most (70%) of the nuclear fallout from the explosion at the Chernobyl power plant located 16 km beyond the border in the neighboring Ukrainian SSR.[84][85]

By the late 1980s, political liberalization led to a national revival, with the Belarusian Popular Front becoming a major pro-independence force.[86][87]

Independence

In March 1990, elections for seats in the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR took place. Though the opposition candidates, mostly associated with the pro-independence Belarusian Popular Front, took only 10% of the seats,[88] Belarus declared itself sovereign on 27 July 1990 by issuing the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic.[89]

Wide-scale strikes erupted in April 1991. With the support of the Communist Party of Byelorussia, the country's name was changed to the Republic of Belarus on 25 August 1991.[90][88] Stanislav Shushkevich, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine on 8 December 1991 in Białowieża Forest to formally declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[88]

In January 1992, the Belarusian Popular Front campaigned for early elections later in the year, two years before they were scheduled. By May of that year, about 383,000 signatures had been collected for a petition to hold the referendum, which was 23,000 more than legally required to be put to a referendum at the time. Despite this, the meeting of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus to ultimately decide the date for said referendum was delayed by six months. However, with no evidence to suggest such, the Supreme Council rejected the petition on the grounds of massive irregularities. Elections for the Supreme Council were set for March 1994. A new law on parliamentary elections failed to pass by 1993. Disputes over the referendum were accredited to the largely conservative Party of Belarusian Communists, which controlled the Supreme Council at the time and was largely opposed to political and economic reform, with allegations that some of the deputies opposed Belarusian independence.[91]

Lukashenko era

A national constitution was adopted in March 1994 in which the functions of prime minister were given to the President of Belarus. A two-round election for the presidency on 24 June 1994 and 10 July 1994[26] catapulted the formerly unknown Alexander Lukashenko into national prominence. He garnered 45% of the vote in the first round and 80%[88] in the second, defeating Vyacheslav Kebich who received 14% of the vote. The elections were the first and only free elections in Belarus after independence.[92]

The 2000s saw a number of economic disputes between Belarus and its primary economic partner, Russia. The first one was the 2004 Russia–Belarus energy dispute when Russian energy giant Gazprom ceased the import of gas into Belarus because of price disagreements. The 2007 Russia–Belarus energy dispute centered on accusations by Gazprom that Belarus was siphoning oil off of the Druzhba pipeline that runs through Belarus. Two years later the so-called Milk War, a trade dispute, started when Russia wanted Belarus to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and through a series of events ended up banning the import of dairy products from Belarus.

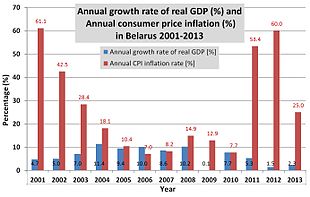

In 2011, Belarus suffered a severe economic crisis attributed to Lukashenko's government's centralized control of the economy, with inflation reaching 108.7%.[93] Around the same time the 2011 Minsk Metro bombing occurred in which 15 people were killed and 204 were injured. Two suspects, who were arrested within two days, confessed to being the perpetrators and were executed by shooting in 2012. The official version of events as publicised by the Belarusian government was questioned in the unprecedented wording of the UN Security Council statement condemning "the apparent terrorist attack" intimating the possibility that the Belarusian government itself was behind the bombing.[94]

Mass protests erupted across the country following the disputed 2020 Belarusian presidential election,[95] in which Lukashenko sought a sixth term in office.[96] Neighbouring countries Poland and Lithuania do not recognize Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus and the Lithuanian government has allotted a residence for main opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and other members of the Belarusian opposition in Vilnius.[97][98][99][100][101] Neither is Lukashenko recognized as the legitimate president of Belarus by the European Union, Canada, the United Kingdom or the United States.[102][103][104][105] The European Union, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States have all imposed sanctions against Belarus because of the rigged election and political oppression during the ongoing protests in the country.[106][107] Further sanctions were imposed in 2022 following the country's role and complicity in the Russian invasion of Ukraine; Russian troops were allowed to stage part of the invasion from Belarusian territory.[108][109] These include not only corporate offices and individual officers of government but also private individuals who work in the state-owned enterprise industrial sector.[110] Norway and Japan have joined the sanctions regime which aims to isolate Belarus from the international supply chain. Most major Belarusian banks are also under restrictions.[110]

Geography

Belarus lies between latitudes 51° and 57° N, and longitudes 23° and 33° E. Its extension from north to south is 560 km (350 mi), from west to east is 650 km (400 mi).[111] It is landlocked, relatively flat, and contains large tracts of marshy land.[112] About 40% of Belarus is covered by forests.[113][114] The country lies within two ecoregions: Sarmatic mixed forests and Central European mixed forests.[115]

Many streams and 11,000 lakes are found in Belarus.[112] Three major rivers run through the country: the Neman, the Pripyat, and the Dnieper. The Neman flows westward towards the Baltic sea and the Pripyat flows eastward to the Dnieper; the Dnieper flows southward towards the Black Sea.[116]

The highest point is Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (Dzyarzhynsk Hill) at 345 metres (1,132 ft), and the lowest point is on the Neman River at 90 m (295 ft).[112] The average elevation of Belarus is 160 m (525 ft) above sea level.[117] The climate features mild to cold winters, with January minimum temperatures ranging from −4 °C (24.8 °F) in southwest (Brest) to −8 °C (17.6 °F) in northeast (Vitebsk), and cool and moist summers with an average temperature of 18 °C (64.4 °F).[118] Belarus has an average annual rainfall of 550 to 700 mm (21.7 to 27.6 in).[118] The country is in the transitional zone between continental climates and maritime climates.[112]

Natural resources include peat deposits, small quantities of oil and natural gas, granite, dolomite (limestone), marl, chalk, sand, gravel, and clay.[112] About 70% of the radiation from neighboring Ukraine's 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster entered Belarusian territory, and about a fifth of Belarusian land (principally farmland and forests in the southeastern regions) was affected by radiation fallout.[119] The United Nations and other agencies have aimed to reduce the level of radiation in affected areas, especially through the use of caesium binders and rapeseed cultivation, which are meant to decrease soil levels of caesium-137.[120][121]

Belarus borders five countries: Latvia to the north, Lithuania to the northwest, Poland to the west, Russia to the north and the east, and Ukraine to the south. Treaties in 1995 and 1996 demarcated Belarus's borders with Latvia and Lithuania, and Belarus ratified a 1997 treaty establishing the Belarus-Ukraine border in 2009.[122] Belarus and Lithuania ratified final border demarcation documents in February 2007.[123]

Government and politics

Belarus, by constitution, is a presidential republic with separation of powers, governed by a president and the National Assembly. However, Belarus has been led by a highly centralized and authoritarian government,[124][4] and has often been described as "Europe's last dictatorship" and president Alexander Lukashenko as "Europe's last dictator"[125] by some media outlets, politicians and authors.[126][127][128][129] Belarus has been considered an autocracy where power is ultimately concentrated in the hands of the president, elections are not free and judicial independence is weak.[130] The Council of Europe removed Belarus from its observer status since 1997 as a response for election irregularities in the November 1996 constitutional referendum and parliament by-elections.[131][132] Re-admission of the country into the council is dependent on the completion of benchmarks set by the council, including the improvement of human rights, rule of law, and democracy.[133]

The term for each presidency is five years. Under the 1994 constitution, the president could serve for only two terms as president, but a change in the constitution in 2004 eliminated term limits.[134] Lukashenko has been the president of Belarus since 1994. In 1996, Lukashenko called for a controversial vote to extend the presidential term from five to seven years, and as a result the election that was supposed to occur in 1999 was pushed back to 2001. The referendum on the extension was denounced as a "fantastic" fake by the chief electoral officer, Viktar Hanchar, who was removed from the office for official matters only during the campaign.[135] The National Assembly is a bicameral parliament comprising the 110-member House of Representatives (the lower house) and the 64-member Council of the Republic (the upper house).[136]

The House of Representatives has the power to appoint the prime minister, make constitutional amendments, call for a vote of confidence on the prime minister, and make suggestions on foreign and domestic policy.[137] The Council of the Republic has the power to select various government officials, conduct an impeachment trial of the president, and accept or reject the bills passed by the House of Representatives. Each chamber has the ability to veto any law passed by local officials if it is contrary to the constitution.[138]

The government includes a Council of Ministers, headed by the prime minister and five deputy prime ministers.[139] The members of this council need not be members of the legislature and are appointed by the president. The judiciary comprises the Supreme Court and specialized courts such as the Constitutional Court, which deals with specific issues related to constitutional and business law. The judges of national courts are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Council of the Republic. For criminal cases, the highest court of appeal is the Supreme Court. The Belarusian Constitution forbids the use of special extrajudicial courts.[138]

Elections

Lukashenko was officially re-elected as president in 2001, in 2006, in 2010, in 2015 and again in 2020, although none of those elections were considered free or fair nor democratic.[140][141][142][143][144][145][146][147][148][149]

Neither the pro-Lukashenko parties, such as the Belarusian Social Sporting Party and the Republican Party of Labour and Justice (RPTS), nor the People's Coalition 5 Plus opposition parties, such as the BPF Party and the United Civic Party, won any seats in the 2004 elections. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) ruled that the elections were unfair because opposition candidates were arbitrarily denied registration and the election process was designed to favor the ruling party.[150]

In the 2006 presidential election, Lukashenko was opposed by Alaksandar Milinkievič, who represented a coalition of opposition parties, and by Alyaksandr Kazulin of the Social Democrats. Kazulin was detained and beaten by police during protests surrounding the All Belarusian People's Assembly. Lukashenko won the election with 80% of the vote; the Russian Federation and the CIS deemed the vote open and fair[151] while the OSCE and other organizations called the election unfair.[152]

After the December completion of the 2010 presidential election, Lukashenko was elected to a fourth straight term with nearly 80% of the vote in elections. The runner-up opposition leader Andrei Sannikov received less than 3% of the vote; independent observers criticized the election as fraudulent. When opposition protesters took to the streets in Minsk, many people, including some presidential candidates, were beaten and arrested by the riot police.[153] Many of the candidates, including Sannikov, were sentenced to prison or house arrest for terms which are mainly and typically over four years.[154][155] Six months later amid an unprecedented economic crisis, activists utilized social networking to initiate a fresh round of protests characterized by wordless hand-clapping.[156]

In the 2012 parliamentary election, 105 of the 110 members elected to the House of Representatives were not affiliated with any political party. The Communist Party of Belarus won 3 seats, and the Belarusian Agrarian Party and RPTS, one each.[157] Most non-partisans represent a wide scope of social organizations such as workers' collectives, public associations, and civil society organizations, similar to the composition of the Soviet legislature.[158]

In the 2020 presidential election, Lukashenko won again with official results giving him 80% of the vote, leading to mass protests. The European Union and the United Kingdom did not recognise the result and the EU imposed sanctions.[159]

Foreign relations

The Byelorussian SSR was one of the two Soviet republics that joined the United Nations along with the Ukrainian SSR as one of the original 51 members in 1945.[160] Belarus and Russia have been close trading partners and diplomatic allies since the breakup of the Soviet Union. Belarus is dependent on Russia for imports of raw materials and for its export market.[161]

The Union State, a supranational confederation between Belarus and Russia, was established in a 1996–99 series of treaties that called for monetary union, equal rights, single citizenship, and a common foreign and defense policy. However, the future of the union has been placed in doubt because of Belarus's repeated delays of monetary union, the lack of a referendum date for the draft constitution, and a dispute over the petroleum trade.[161][162] Belarus was a founding member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).[163] Belarus has trade agreements with several European Union member states (despite other member states' travel ban on Lukashenko and top officials),[164] including neighboring Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland.[165] Travel bans imposed by the European Union have been lifted in the past in order to allow Lukashenko to attend diplomatic meetings and also to engage his government and opposition groups in dialogue.[166]

Bilateral relations with the United States are strained; the United States had not had an ambassador in Minsk since 2007 and Belarus never had an ambassador in Washington since 2008.[167][168] Diplomatic relations remained tense, and in 2004, the United States passed the Belarus Democracy Act, which authorized funding for anti-government Belarusian NGOs, and prohibited loans to the Belarusian government, except for humanitarian purposes.[169]

Relations between China and Belarus are close,[170] with Lukashenko visiting China multiple times during his tenure.[171] Belarus also has strong ties with Syria,[172] considered a key partner in the Middle East.[173] In addition to the CIS, Belarus is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (previously the Eurasian Economic Community), the Collective Security Treaty Organization,[165] the international Non-Aligned Movement since 1998,[174] and the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). As an OSCE member state, Belarus's international commitments are subject to monitoring under the mandate of the U.S. Helsinki Commission.[175] Belarus is included in the European Union's Eastern Partnership program, part of the EU's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims to bring the EU and its neighbours closer in economic and geopolitical terms.[176] However, Belarus suspended its participation in the Eastern Partnership program on 28 June 2021, after the EU imposed more sanctions against the country.[177][178]

Military

Lieutenant General Viktor Khrenin heads the Ministry of Defence,[179] and Alexander Lukashenko (as president) serves as Commander-in-Chief.[138] The armed forces were formed in 1992 using parts of the former Soviet Armed Forces on the new republic's territory. The transformation of the ex-Soviet forces into the Armed Forces of Belarus, which was completed in 1997, reduced the number of its soldiers by 30,000 and restructured its leadership and military formations.[180]

Most of Belarus's service members are conscripts, who serve for 12 months if they have higher education or 18 months if they do not.[181] Demographic decreases in the Belarusians of conscription age have increased the importance of contract soldiers, who numbered 12,000 in 2001.[182] In 2005, about 1.4% of Belarus's gross domestic product was devoted to military expenditure.[183]

Belarus has not expressed a desire to join NATO but has participated in the Individual Partnership Program since 1997,[184] and Belarus provided refueling and airspace support for the International Security Assistance Force mission in Afghanistan.[185] Belarus first began to cooperate with NATO upon signing documents to participate in their Partnership for Peace Program in 1995.[186] However, Belarus cannot join NATO because it is a member of the CSTO. Tensions between NATO and Belarus peaked after the March 2006 presidential election in Belarus.[187]

Human rights and corruption

This article appears to be slanted towards recent events. (November 2022) |

Amnesty International,[188] and Human Rights Watch[189] have criticized Lukashenko's violations of human rights. Belarus's Democracy Index rating is the lowest in Europe, the country is labelled as "not free" by Freedom House,[190] as "repressed" in the Index of Economic Freedom, and in the Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, Belarus is ranked 153th out of 180 countries for 2022.[191] The Belarusian government is also criticized for human rights violations and its persecution of non-governmental organizations, independent journalists, national minorities, and opposition politicians.[188][189] Lukashenko announced a new law in 2014 that will prohibit kolkhoz workers (around 9% of total work force) from leaving their jobs at will—a change of job and living location will require permission from governors. The law was compared with serfdom by Lukashenko himself.[192][193] Similar regulations were introduced for the forestry industry in 2012.[194] Belarus is the only European country still using capital punishment, having carried out executions in 2011.[195] LGBT rights in the country are also ranked among the lowest in Europe.[196] In March 2023, Lukashenko signed a law which allows to use capital punishment against officials and soldiers convicted of high treason.[197]

The judicial system in Belarus lacks independence and is subject to political interference.[198] Corrupt practices such as bribery often took place during tender processes, and whistleblower protection and national ombudsman are lacking in Belarus's anti-corruption system.[199]

On 1 September 2020, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights declared that its experts received reports of 450 documented cases of torture and ill-treatment of people who were arrested during the protests following the presidential election. The experts also received reports of violence against women and children, including sexual abuse and rape with rubber batons.[200] At least three detainees suffered injuries indicative of sexual violence in Okrestino prison in Minsk or on the way there. The victims were hospitalized with intramuscular bleeding of the rectum, anal fissure and bleeding, and damage to the mucous membrane of the rectum.[201] In an interview from September 2020 Lukashenko claimed that detainees faked their bruises, saying, "Some of the girls there had their butts painted in blue".[202]

On 23 May 2021, Belarusian authorities forcibly diverted a Ryanair flight from Athens to Vilnius in order to detain opposition activist and journalist Roman Protasevich along with his girlfriend; in response, the European Union imposed stricter sanctions on Belarus.[203] In May 2021, Lukashenko threatened that he will flood the European Union with migrants and drugs as a response to the sanctions.[204] In July 2021, Belarusian authorities launched a hybrid warfare by human trafficking of migrants to the European Union.[205] Lithuanian authorities and top European officials Ursula von der Leyen, Josep Borrell condemned the usage of migrants as a weapon and suggested that Belarus could be subject to further sanctions.[206] In August 2021, Belarusian officials, wearing uniforms, riot shields and helmets, were recorded on camera near the Belarus–Lithuania border pushing and urging the migrants to cross the European Union border.[207] Following the granting of humanitarian visas to an Olympic athlete Krystsina Tsimanouskaya and her husband, Poland also accused Belarus for organizing a hybrid warfare as the number of migrants crossing the Belarus–Poland border sharply increased multiple times when compared to the 2020 statistics.[208][209] Illegal migrants numbers also exceeded the previous annual numbers in Latvia.[210] On 2 December 2021, the United States, European Union, United Kingdom and Canada imposed new sanctions on Belarus.[211]

Administrative divisions

Belarus is divided into six regions called oblasts (Belarusian: вобласць; Russian: область), which are named after the cities that serve as their administrative centers: Brest, Gomel, Grodno, Mogilev, Minsk, and Vitebsk.[212] Each region has a provincial legislative authority, called a region council (Belarusian: абласны Савет Дэпутатаў; Russian: Областной Совет депутатов), which is elected by its residents, and a provincial executive authority called a region administration (Belarusian: абласны выканаўчы камітэт; Russian: областной исполнительный комитет), whose chairman is appointed by the president.[213] The regions are further subdivided into 118 raions, commonly translated as districts (Belarusian: раён; Russian: район).[212] Each raion has its own legislative authority, or raion council, (Belarusian: раённы Савет Дэпутатаў; Russian: районный Совет депутатов) elected by its residents, and an executive authority or raion administration appointed by oblast executive powers.[113] The city of Minsk is split into nine districts and enjoys special status as the nation's capital at the same administration level as the oblasts.[214] It is run by an executive committee and has been granted a charter of self-rule.[215]

Local government

Local government in Belarus is administered by administrative-territorial units (Belarusian: адміністрацыйна-тэрытарыяльныя адзінкі; Russian: административно-территориальные единицы), and occurs on two levels: basic and primary. At the basic level are 118 raions councils and 10 cities of oblast subordination councils, which are supervised by the governments of the oblasts.[216] At the primary level are 14 cities of raion subordination councils, 8 urban-type settlements councils, and 1,151 village councils.[217][218] The councils are elected by their residents, and have executive committees appointed by their executive committee chairs. The chairs of executive committees for raions and city of oblast subordinations are appointed by the regional executive committees at the level above; the chairs of executive committees for towns of raion subordination, settlements and villages are appointed by their councils, but upon the recommendation of the raion executive committees.[216] In either case, the councils have the power to approve or reject a nonimee for executive committee chair.

Settlements without their own local council and executive committee are called territorial units (Belarusian: тэрытарыяльныя адзінкі; Russian: территориальные единицы). These territorial units may also be classified as a city of regional or raion subordination, urban-type settlement or rural settlement, but whose government is administered by the council of another primary or basic unit.[219] In October 1995, a presidential decree abolished the local governments of cities of raion subordination and urban-type settlements which served as the administrative center of raions, demoting them from administrative-territorial units to territorial units.[220]

As for 2019, the administrative-territorial and territorial units include 115 cities, 85 urban-type settlements, and 23,075 rural settlements.[221]

Economy

Belarus is a developing country, but at 60th place in the United Nations' Human Development Index, it has a "very high" human development.[222] It is one of the most equal countries in the world,[223] with one of the lowest Gini-coefficient measures of national resource distribution, and it ranks 82nd in GDP per capita. In 2019, the share of manufacturing in GDP was 31%, over two-thirds of this amount fell on manufacturing industries.[clarification needed] Manufacturing employed 34.7% of the workforce.[224] Manufacturing growth is much smaller than for the economy as a whole—about 2.2% in 2021. Important agricultural products include potatoes and cattle byproducts, including meat.[225]

Trade

Belarus has trade relations with over 180 countries. As of 2007, its main trading partners were Russia, which accounted for about 45% of Belarusian exports and 55% of imports (which include petroleum),[226] and the EU countries, with 25% of exports and 20% of imports.[227][228][needs update]

In April 2022, as a result of its facilitation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU imposed trade sanctions on Belarus.[229] The sanctions were extended and expanded in August 2023.[230] These sanctions are in addition to those imposed following the rigged 2020 "election" of Lukashenko.[231]

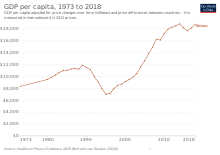

At the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Belarus was one of the world's most industrially developed states by proportion of GDP and the richest CIS member-state.[232] In 2015, 39.3% of Belarusians were employed by state-controlled companies, 57.2% by private companies (in which the government has a 21.1% stake) and 3.5% by foreign companies.[233] In 1994, Belarus's main exports included heavy machinery (especially tractors), agricultural products, and energy products.[234] Economically, Belarus involved itself in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Eurasian Economic Community, and Union with Russia.[235] In the 1990s, industrial production plunged due to decreases in imports, investment, and demand for Belarusian products from its trading partners.[236] GDP only began to rise in 1996;[237] the country was the fastest-recovering former Soviet republic in the terms of its economy.[238] In 2006, GDP amounted to US$83.1 billion in purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars (estimate), or about $8,100 per capita.[225] In 2005, GDP increased by 9.9%; the inflation rate averaged 9.5%.[225] Belarus was ranked 80th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[239]

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, under Lukashenko's leadership, Belarus has maintained government control of key industries and eschewed the large-scale privatizations seen in other former Soviet republics.[240]

Belarus applied to become a member of the World Trade Organization in 1993.[241] Due to its failure to protect labor rights, including passing laws forbidding unemployment or working outside state-controlled sectors,[242] Belarus lost its EU Generalized System of Preferences status on 21 June 2007, which raised tariff rates to their prior most favored nation levels.[243]

Employment

The labor force consists of more than 4 million people, of whom women are slightly more than men.[233] In 2005, nearly a quarter of the population was employed in industrial factories. Employment is also high in agriculture, manufacturing sales, trading goods, and education. The unemployment rate was 1.5% in 2005, according to government statistics. There were 679,000 unemployed Belarusians, of whom two-thirds were women. The unemployment rate has been declining since 2003, and the overall rate of employment is the highest since statistics were first compiled in 1995.[233]

Currency

The currency of Belarus is the Belarusian ruble. The currency was introduced in May 1992 to replace the Soviet ruble and it has undergone redenomination twice since then. The first coins of the Republic of Belarus were issued on 27 December 1996.[244] The ruble was reintroduced with new values in 2000 and has been in use ever since.[245] In 2007, The National Bank of Belarus abandoned pegging the Belarusian ruble to the Russian ruble.[246] As part of the Union of Russia and Belarus, the two states have discussed using a single currency analogous to the Euro. This led to a proposal that the Belarusian ruble be discontinued in favor of the Russian ruble (RUB), starting as early as 1 January 2008.

On 23 May 2011, the ruble depreciated 56% against the United States dollar. The depreciation was even steeper on the black market and financial collapse seemed imminent as citizens rushed to exchange their rubles for dollars, euros, durable goods, and canned goods.[247] On 1 June 2011, Belarus requested an economic rescue package from the International Monetary Fund.[248][249] A new currency, the new Belarusian ruble (ISO 4217 code: BYN)[250] was introduced in July 2016, replacing the Belarusian ruble in a rate of 1:10,000 (10,000 old ruble = 1 new ruble). From 1 July until 31 December 2016, the old and new currencies were in parallel circulation and series 2000 notes and coins could be exchanged for series 2009 from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2021.[250] This redenomination can be considered an effort to fight the high inflation rate.[251][252] On 6 October 2022, Lukashenko banned price increases, to combat food inflation.[253] In January 2023, Belarus legalized copyright infringement of media and intellectual property created by "unfriendly" foreign nations.[254]

The banking system of Belarus consists of two levels: Central Bank (National Bank of the Republic of Belarus) and 25 commercial banks.[255]

Demographics

According to the 2019 census the population was 9.41 million[256] with ethnic Belarusians constituting 84.9% of Belarus's total population.[256] Minority groups include: Russians (7.5%), Poles (3.1%), and Ukrainians (1.7%).[256]Belarus has a population density of about 50 people per square kilometre (127 per sq mi); 70% of its total population is concentrated in urban areas.[257] Minsk, the nation's capital and largest city, was home to 1,937,900 residents in 2015[update].[258] Gomel, with a population of 481,000, is the second-largest city and serves as the capital of the Gomel Region. Other large cities are Mogilev (365,100), Vitebsk (342,400), Grodno (314,800) and Brest (298,300).[259]

Like many other Eastern European countries, Belarus has a negative population growth rate and a negative natural growth rate. In 2007, Belarus's population declined by 0.41% and its fertility rate was 1.22,[260] well below the replacement rate. Its net migration rate is +0.38 per 1,000, indicating that Belarus experiences slightly more immigration than emigration. As of 2015[update], 69.9% of Belarus's population is aged 14 to 64; 15.5% is under 14, and 14.6% is 65 or older. Its population is also aging; the median age of 30–34 is estimated to rise to between 60 and 64 in 2050.[261] There are about 0.87 males per female in Belarus.[260] The average life expectancy is 72.15 (66.53 years for men and 78.1 years for women).[260] Over 99% of Belarusians aged 15 and older are literate.[260]

Largest cities or towns in Belarus Source? | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Municipal pop. | ||||||

Minsk  Gomel | 1 | Minsk | Minsk Region | 1,992,685 |  Mogilev  Vitebsk | ||||

| 2 | Gomel | Gomel Region | 536,938 | ||||||

| 3 | Mogilev | Mogilev Region | 383,313 | ||||||

| 4 | Vitebsk | Vitebsk Region | 378,459 | ||||||

| 5 | Grodno | Grodno Region | 373,547 | ||||||

| 6 | Brest | Brest Region | 350,616 | ||||||

| 7 | Babruysk | Mogilev Region | 216,793 | ||||||

| 8 | Baranavichy | Brest Region | 179,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Barysaw | Minsk Region | 142,681 | ||||||

| 10 | Pinsk | Brest Region | 137,960 | ||||||

Religion

According to the census of November 2011, 58.9% of all Belarusians adhered to some kind of religion; out of those, Eastern Orthodoxy made up about 82%: Eastern Orthodox in Belarus are mainly part of the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church, though a small Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church also exists.[262] Roman Catholicism is practiced mostly in the western regions, and there are also different denominations of Protestantism.[263][264] Minorities also practice Greek Catholicism, Judaism, Islam and neo-paganism. Overall, 48.3% of the population is Orthodox Christian, 41.1% is not religious, 7.1% is Roman Catholic and 3.3% follows other religions.[262]

Belarus's Catholic minority is concentrated in the western part of the country, especially around Grodno, consisting in a mixture of Belarusians and the country's Polish and Lithuanian minorities.[265] President Lukashenko has stated that Orthodox and Catholic believers are the "two main confessions in our country".[266]

Belarus was once a major center of European Jews, with 10% of the population being Jewish. But since the mid-20th century, the number of Jews has been reduced by the Holocaust, deportation, and emigration, so that today it is a very small minority of less than one percent.[267] The Lipka Tatars, numbering over 15,000, are predominantly Muslims. According to Article 16 of the Constitution, Belarus has no official religion. While the freedom of worship is granted in the same article, religious organizations deemed harmful to the government or social order can be prohibited.[212]

Languages

Belarus's two official languages are Russian and Belarusian;[268] Russian is the most common language spoken at home, used by 70% of the population, while Belarusian, the official first language, is spoken at home by 23%.[269] Minorities also speak Polish, Ukrainian and Eastern Yiddish.[270] Belarusian, although not as widely used as Russian, is the mother tongue of 53.2% of the population, whereas Russian is the mother tongue of only 41.5%.[269] Following the election of Alexander Lukashenko, most schools in major cities began to teach in Russian rather than Belarusian.[271] The annual circulation of Belarusian-language literature also significantly decreased from 1990 to 2020.[272]

Culture

Arts and literature

The Belarusian government sponsors annual cultural festivals such as the Slavianski Bazaar in Vitebsk,[273] which showcases Belarusian performers, artists, writers, musicians, and actors. Several state holidays, such as Independence Day and Victory Day, draw big crowds and often include displays such as fireworks and military parades, especially in Vitebsk and Minsk.[274] The government's Ministry of Culture finances events promoting Belarusian arts and culture both inside and outside the country.

Belarusian literature[275] began with 11th- to 13th-century religious scripture, such as the 12th-century poetry of Cyril of Turaw.[276]

By the 16th century, Polotsk resident Francysk Skaryna translated the Bible into Belarusian. It was published in Prague and Vilnius sometime between 1517 and 1525, making it the first book printed in Belarus or anywhere in Eastern Europe.[277] The modern era of Belarusian literature began in the late 19th century; one prominent writer was Yanka Kupala. Many Belarusian writers of the time, such as Uładzimir Žyłka, Kazimir Svayak, Yakub Kolas, Źmitrok Biadula, and Maksim Haretski, wrote for Nasha Niva, a Belarusian-language paper published that was previously published in Vilnius but now is published in Minsk.[278]

After Belarus was incorporated into the Soviet Union, the Soviet government took control of the Republic's cultural affairs. At first, a policy of "Belarusianization" was followed in the newly formed Byelorussian SSR. This policy was reversed in the 1930s, and the majority of prominent Belarusian intellectuals and nationalist advocates were either exiled or killed in Stalinist purges.[279] The free development of literature occurred only in Polish-held territory until Soviet occupation in 1939. Several poets and authors went into exile after the Nazi occupation of Belarus and would not return until the 1960s.[277]

The last major revival of Belarusian literature occurred in the 1960s with novels published by Vasil Bykaŭ and Uladzimir Karatkievich. An influential author who devoted his work to awakening the awareness of the catastrophes the country has suffered, was Ales Adamovich. He was named by Svetlana Alexievich, the Belarusian winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature 2015, as "her main teacher, who helped her to find a path of her own".[280]

Музыка в Беларуси во многом включает в себя богатые традиции народной и религиозной музыки. Традиции народной музыки страны восходят к временам Великого княжества Литовского . В XIX веке польский композитор Станислав Монюшко, живя в Минске, сочинял оперы и камерные произведения. Во время своего пребывания он работал с белорусским поэтом Винцентом Дуниным-Марцинкевичем и создал оперу «Селянка» ( «Крестьянка» ). В конце XIX века в крупных городах Беларуси сформировались собственные оперные и балетные труппы. Балет М. Крошнера «Соловей» был написан еще в советское время и стал первым белорусским балетом, представленным на сцене Национального академического театра балета имени Вяликов в Минске. [281] [ нужен лучший источник ]

После Второй мировой войны музыка была посвящена невзгодам белорусского народа или тем, кто взялся за оружие на защиту Родины. В этот период Анатолий Богатырев , создатель оперы « В полесской девственной пуще ». «учителем» белорусских композиторов выступил [282] Национальный академический театр балета в Минске был удостоен премии «Бенуа де ла данс» в 1996 году как лучшая балетная труппа мира. [282] В последние годы рок-музыка становится все более популярной, хотя правительство Беларуси пытается ограничить количество зарубежной музыки, транслируемой по радио, в пользу традиционной белорусской музыки. С 2004 года Беларусь отправляет артистов на конкурс песни «Евровидение» . [283] [284]

Марк Шагал родился в Лиозне (под Витебском он провел ) в 1887 году. Годы Первой мировой войны в Советской Белоруссии, став одним из самых выдающихся художников страны, представителем модернистского авангарда , а также основателем Витебского художественного училища. . [285] [286]

Одеваться

Традиционное белорусское платье берет свое начало еще со времен Киевской Руси . Из-за прохладного климата одежда предназначалась для сохранения тепла тела и обычно шилась из льна или шерсти . Они были украшены витиеватыми узорами под влиянием соседних культур: поляков, литовцев, латышей, русских и других европейских народов. В каждом регионе Беларуси разработаны определенные шаблоны проектирования. [287] Один орнамент, распространенный в ранних платьях, в настоящее время украшает подъём белорусского национального флага , принятого на спорном референдуме в 1995 году. [288]

Кухня

Белорусская кухня состоит в основном из овощей, мяса (особенно свинины) и хлеба. Продукты обычно либо медленно готовятся, либо тушатся . Обычно белорусы едят легкий завтрак и два сытных приема пищи в течение дня. В Беларуси потребляют пшеничный и ржаной хлеб, но ржи больше, потому что условия слишком суровы для выращивания пшеницы. В знак гостеприимства хозяин традиционно преподносит подношение хлеба-соли , приветствуя гостя или посетителя. [289]

Спорт

Эта статья , кажется, ориентирована на недавние события . ( ноябрь 2020 г. ) |

Беларусь участвует в Олимпийских играх после зимних Олимпийских игр 1994 года как независимая страна. Получая мощную спонсорскую поддержку со стороны правительства, хоккей с шайбой является вторым по популярности видом спорта в стране после футбола . Национальная сборная по футболу никогда не квалифицировалась на крупный турнир; однако БАТЭ Борисов играл в Лиге чемпионов . Национальная хоккейная сборная заняла четвертое место на Олимпийских играх в Солт-Лейк-Сити в 2002 году после памятной досадной победы над Швецией в четвертьфинале и регулярно участвует в чемпионатах мира , часто выходя в четвертьфинал. Многочисленные белорусские игроки присутствуют в Континентальной хоккейной лиге Евразии, особенно в белорусском клубе ХК «Динамо Минск» , а некоторые также играли в Национальной хоккейной лиге в Северной Америке. Чемпионат мира по хоккею с шайбой 2014 года проходил в Беларуси, а чемпионат мира по хоккею с шайбой 2021 года должен был пройти совместно в Латвии и Беларуси, но был отменен из-за массовых протестов и проблем безопасности. Чемпионат Европы по велоспорту на легкой атлетике УЭК 2021 года также был отменен, поскольку Беларусь не считалась безопасной принимающей стороной.

Дарья Домрачева — ведущая биатлонистка , на счету которой три золотые медали на зимних Олимпийских играх 2014 года . [290] Теннисистка в Виктория Азаренко стала первой белоруской, выигравшей титул Большого шлема в одиночном разряде на Открытом чемпионате Австралии по теннису 2012 году. [291] Она также выиграла золотую медаль в смешанном парном разряде на летних Олимпийских играх 2012 года вместе с Максом Мирным , обладателем десяти титулов Большого шлема в парном разряде .

Среди других известных белорусских спортсменов - велосипедист Василий Кириенко , выигравший чемпионат мира по гонкам на время в 2015 году , и бегунья на средние дистанции Марина Арзамасова , завоевавшая золотую медаль на дистанции 800 метров на чемпионате мира по легкой атлетике 2015 года . Андрей Арловский , родившийся в Бобруйске Белорусской ССР , является действующим бойцом UFC и бывшим чемпионом мира UFC в тяжелом весе .

Беларусь также известна своими сильными художественными гимнастками. Среди заметных гимнасток - Инна Жукова , завоевавшая серебро на Олимпийских играх 2008 года в Пекине , Любовь Черкашина , завоевавшая бронзу на Олимпийских играх в Лондоне в 2012 году, и Мелитина Станюта , бронзовый призер чемпионата мира 2015 года в многоборье. Белорусская взрослая группа завоевала бронзу на Олимпийских играх в Лондоне в 2012 году .

Телекоммуникации

- Код страны: .by

Государственная телекоммуникационная монополия «Белтелеком» обладает эксклюзивным правом соединения с интернет-провайдерами за пределами Беларуси. Белтелекому принадлежат все магистральные каналы, которые связаны с интернет-провайдерами Lattelecom, TEO LT, Tata Communications (бывший Teleglobe ), Synterra, Ростелеком , Транстелеком и МТС. «Белтелеком» — единственный оператор, имеющий лицензию на предоставление коммерческих услуг VoIP в Беларуси. [292]

Объекты всемирного наследия

В Беларуси есть четыре : ЮНЕСКО объекта Всемирного наследия Мирский замковый комплекс , Несвижский замок , Беловежская пуща (совместно с Польшей ) и Геодезическая дуга Струве (совместно с девятью другими странами). [293]

См. также

Примечания

- ↑ Ряд стран не признают Лукашенко легитимным президентом Беларуси после президентских выборов в Беларуси 2020 года . [5] [6]

- ^ / ˌ b ɛ l ə ˈ r uː s / BEL -ə- ROOSS , США также / ˌ b iː l ə ˈ r uː s / BEE -lə- ROOSS , Великобритания также / ˈ b ɛ l ə r ʌ s , - r ʊ s / BEL -ə-ru(u)ss ; Белорусский : Белоруссия , латинизированный : Белоруссия , ВЛИЯНИЕ: [bʲɛlaˈrusʲ] ; Russian : Беларусь , IPA: [bʲɪlɐˈrusʲ] ; альтернативно и ранее известное как Белоруссия (от русского Белоруссия ), имя, которое часто запрещается в Беларуси, хотя широко используется в России.

- ^ Belarusian: Рэспубліка Беларусь , romanized: Respublika Byelarus , IPA: [rɛsˈpublʲika bʲɛlaˈrusʲ] ; Russian: Республика Беларусь , romanized: Respublika Belarus , IPA: [rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə bʲɪlɐˈrusʲ] .

Ссылки

- ^ «Беларусь в цифрах 2021» (PDF) . Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь. 2021. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 октября 2022 года.

- ^ «Поколения и гендерное исследование, Беларусь, волна 1, 2020» . ggpsurvey.ined.fr . Архивировано из оригинала 16 октября 2022 года . Проверено 25 августа 2019 г.

- ^ «Беларусь» . Всемирная книга фактов ЦРУ . Проверено 16 октября 2022 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Джон Р. Шорт (25 августа 2021 г.). Геополитика: осмысление меняющегося мира . Роуман и Литтлфилд. стр. 163 и далее . ISBN 978-1-5381-3540-2 . OCLC 1249714156 .

- ^ «Лидер Беларуси Лукашенко проводит тайную инаугурацию на фоне продолжающихся протестов» . France24.com . 23 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Беларусь: Массовые протесты после тайной присяги Лукашенко» . Новости Би-би-си. 23 сентября 2020 г.

Несколько стран ЕС и США заявляют, что не признают Лукашенко законным президентом Беларуси.

- ^ «Лукашенко назначает новое правительство» . eng.belta.by. 19 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Население на начало 2024 года» (PDF) . belstat.gov.by .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д «База данных «Перспективы развития мировой экономики», выпуск за октябрь 2023 г. (Беларусь)» . МВФ.org . Международный валютный фонд . 10 октября 2023 г. Проверено 13 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Индекс GINI (оценка Всемирного банка) – Беларусь» . Всемирный банк . Проверено 12 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Отчет о человеческом развитии 2023/24» (PDF) . Программа развития ООН . 13 марта 2024 г. Проверено 13 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Изменение часового пояса и часов в Минске, Беларусь» . timeanddate.com.

- ^ «Icann одобрил заявку Беларуси на делегирование домена первого уровня с поддержкой алфавитов национальных языков.Бел» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 года . Проверено 26 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Минахан 1998 , с. 35.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Запрудник 1993 , с. 2

- ↑ О происхождении названий Белой и Чёрной Малороссии (англ. «О происхождении названий Белой и Чёрной Малороссии»), Джозеф Юхо, 1956.

- ^ «Почему Беларусь называют Белой Россией | Belarus Travel» . 5 апреля 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 31 мая 2021 г. Проверено 12 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Вошез, Добсон и Лапидж 2001 , стр. 163

- ^ Белый, Союзники (2000). Летопись Белой Руси: очерк истории одного географического названия . Минск, Беларусь: Энциклопедия. ISBN 985-6599-12-1 .

- ^ Плохий 2001 , с. 327

- ^ Филип Г. Редер (2011). Откуда берутся национальные государства: институциональные изменения в эпоху национализма . Издательство Принстонского университета. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3 .

- ^ Фишман, Джошуа; Гарсия, Офелия (2011). Справочник по языку и этнической идентичности: Континуум успехов и неудач в усилиях по обеспечению языковой и этнической идентичности . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1 .

- ^ Ричмонд 1995 , с. 260

- ^ Иоффе, Григорий (2008). Понимание Беларуси и то, как западная внешняя политика не попадает в цель . Издательство Rowman & Littlefield. п. 41. ИСБН 978-0-7425-5558-7 .

- ^ «Закон Республики Беларусь – О названии Республики Беларусь» (на русском языке). Право – Закон Республики Беларусь. 19 сентября 1991 года . Проверено 6 октября 2007 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Беларусь» . Всемирная книга фактов (изд. 2024 г.). Центральное разведывательное управление . Проверено 22 декабря 2007 г. (Архивное издание 2007 г.)

- ^ " "Беларусь" vs "Белоруссия": ставим точку в вопросе" . Onliner (in Russian). 26 February 2014.

- ^ " "Гудия" и "Балтарусия"?" . Государственная комиссия литовского языка (на литовском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ «Литва отказывается называть Беларусь «Белоруссией» » . Телеграф.by . 16 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ Дзернович, Олег (2013). «Гудас как историческое название белорусов на литовском языке: «готы» или «варвары»?» . Беларусь и ее соседи: исторические представления и политические конструкции. Материалы международной конференции . Варшава: Uczelnia Lazarskiego. стр. 56–68. Архивировано из оригинала 1 мая 2021 года . Проверено 1 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Шоу, Ян; Джеймсон, Роберт (2008). Словарь археологии . Уайли. стр. 203–204. ISBN 978-0-470-75196-1 .

- ^ Запрудник 1993 , с. 7

- ^ Джон Хейвуд, Исторический атлас, древний и классический мир (1998).

- ^ Плохий, Сергей (2006). Происхождение славянских народов . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 94–95. ISBN 0-521-86403-8 .

- ^ Робинсон, Чарльз Генри (1917). Преобразование Европы . Лонгманс, Грин. стр. 491–492. ISBN 978-0-00-750296-7 .

- ^ НН (1914). Новгородская летопись, 1016–1471 гг . Перевод Мичелла, Роберта; Форбс, Невилл. Введение К. Рэймонда Бизли. Текст сообщения А.А. Шахматова. Лондон, Офисы общества. п. 41.

- ^ Ermalovich, Mikola (1991). Pa sliadakh adnago mifa (Tracing one Myth) . Minsk: Navuka i tekhnika. ISBN 978-5-343-00876-0 .

- ^ Запрудник 1993 , с. 27

- ^ Лерски, Джордж Ян; Александр Гейштор (1996). Исторический словарь Польши, 966–1945 гг . Гринвуд Пресс . стр. 181–82. ISBN 0-313-26007-9 .

- ^ Новак, Анджей (1 января 1997 г.). «Русско-польское историческое противостояние» . Сарматское обозрение XVII . Университет Райса . Архивировано из оригинала 18 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 22 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Роуэлл, Южная Каролина (2005). «Балтийская Европа». В Джонсе, Майкл (ред.). Новая Кембриджская средневековая история (Том 6) . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 710. ИСБН 0-521-36290-3 .

- ^ Луковский, Ежи ; Завадски, Юбер (2001). Краткая история Польши (1-е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1 .

- ^ Рясановский, Николай Васильевич (1999). История России (6-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-512179-7 .

- ^ «Белорусский»: Проект языковых материалов Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. Архивировано 22 декабря 2015 г. на Wayback Machine , ucla.edu; по состоянию на 4 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Шойх, ЕК; Дэвид Скиулли (2000). Общества, корпорации и национальное государство . Брилл. п. 187. ИСБН 90-04-11664-8 .

- ^ Биргерсон 2002 , с. 101

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Олсон, Паппас и Паппас 1994 , с. 95

- ^ (in Russian) Воссоединение униатов и исторические судьбы Белорусского народа ( Vossoyedineniye uniatov i istoričeskiye sud'bi Belorusskogo naroda ), Pravoslavie portal

- ^ Житко, Российская политика... , с. 551.

- ^ Иван Петрович Корнилов (1908). Русское дєло в Сєверо-Западном крає: материиалы для историии Виленскаго учебнаго округа преимущественно в Муравьевскую эпоху (in Russian). Тип. А.С. Суворина.

- ^ Д. Марплс (1996). Беларусь: от советской власти к ядерной катастрофе . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан, Великобритания. п. 26. ISBN 978-0-230-37831-5 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Биргерсон 2002 , стр. 105–106

- ^ Иоффе, Григорий (2008). Понимание Беларуси и то, как западная внешняя политика не попадает в цель . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. с. 57. ИСБН 978-0-7425-5558-7 .

- ^ Тимоти Снайдер (2002). Реконструкция наций . Издательство Йельского университета. п. 282. ИСБН 978-0-300-12841-3 .

- ^ «Последней диктатуре Европы противостоит старейшее в мире правительство в изгнании» . 26 января 2016 г.

- ^ Виталий Силицкий-младший; Ян Запрудник (7 апреля 2010 г.). Беларусь от А до Я. Пугало Пресс. стр. 308–. ISBN 978-1-4617-3174-0 .

- ^ Раух, Георг фон (1974). «Ранние этапы независимости» . В Джеральде Онне (ред.). Страны Балтии: годы независимости – Эстония, Латвия, Литва, 1917–40 . К. Херст и Ко, стр. 100–102. ISBN 0-903983-00-1 .

- ^ Желиговский, Люциан (1943). Zapomniane prawdy (PDF) (на польском языке). Ф. Милднер и сыновья. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 октября 2022 года.

- ^ Иоффе, Григорий Викторович; Силицкий, Виталий (2018). Исторический словарь Беларуси (3-е изд.). Лэнхэм (Мэриленд): Роуман и Литтлфилд. п. 282. ИСБН 978-1-5381-1706-4 .

- ^ Марплс, Дэвид (1999). Беларусь: денационализированная нация . Рутледж. п. 5. ISBN 90-5702-343-1 .

- ^ «История Беларуси» . Официальный сайт Республики Беларусь. Архивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2017 года . Проверено 17 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Зорге, Арндт (2005). Глобальное и локальное: понимание диалектики бизнес-систем . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-19-153534-5 .

- ^ Ник Бэрон; Питер Гатрелл (2004). «Война, перемещение населения и государственное образование в российском приграничье 1914–1924 гг.» . Родины . Гимн Пресс. п. 19. ISBN 978-1-84331-385-4 . Проверено 18 сентября 2015 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Норман Дэвис , Божья площадка (польское издание), второй том, стр. 512–513.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д «Польско-белорусские отношения в условиях советской оккупации (1939–1941)» . Архивировано из оригинала 23 июня 2008 года.

- ^ Миронович, Евгениуш (2007). Белорусы и украинцы в политике лагеря Пилсудского [ Белорусы и украинцы в политике лагеря Пилсудского ] (на польском языке). стр. 4–5. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1 .

- ^ Бидер, Х. (2000): Деноминация, этническая принадлежность и язык в Беларуси в 20 веке. В: Журнал славистики 45 (2000), 200–214.

- ^ Любачко, Иван (1972). Белоруссия под властью СССР, 1917–1957 гг . Университетское издательство Кентукки. п. 137.

- ^ Абделал, Рави (2001). Национальная цель в мировой экономике: постсоветские государства в сравнительной перспективе . Издательство Корнелльского университета . ISBN 978-0-8014-3879-0 .

- ^ Группа Тейлора и Фрэнсиса (2004). Всемирный год Европы, Книга 1 . Европейские публикации . ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1 .

- ^

- Клоков В. Я. Великий освободительный поход Красной Армии. (Освобождение Западной Украины и Западной Белоруссии).-Воронеж, 1940.

- Минаев В. Западная Белоруссия и Западная Украина под гнетом панской Польши.—М., 1939.

- Трайнин И.Национальное и социальное освобождение Западной Украины и Западной Белоруссии.—М., 1939.—80 с.

- История Беларуси. Том пятый.—Минск, 2006.—с. 449–474

- ^ Эндрю Уилсон (2011). Беларусь: последняя европейская диктатура . Издательство Йельского университета. ISBN 978-0-300-13435-3 .

- ^ Снайдер, Тимоти (2010). Кровавые земли: Европа между Гитлером и Сталиным . Основные книги. п. 160. ISBN 0465002390

- ^ (немецкий) Даллин, Александр (1958). Немецкое правление в России, 1941–1945: исследование оккупационной политики , стр. 234–236. Дросте Верлаг ГмбХ, Дюссельдорф.

- ^ Экселер, Франциска. «Что вы делали во время войны?: Личные ответы на последствия нацистской оккупации» . Исследования Kritika в истории России и Евразии : 807 – через ResearchGate.

- ^ Иоффе, Григорий (6 февраля 2015 г.). «Партизанское движение в Белоруссии в годы Великой Отечественной войны (часть вторая)» . Фонд Джеймстауна . Проверено 29 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Чернышова, Наталья (15 июня 2022 г.). «Беларусь» . Семнадцать мгновений советской истории . Проверено 29 марта 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Иоффе, Григорий (декабрь 2003 г.). «Понимая Беларусь: белорусская идентичность» . Европа-Азиатские исследования . 55 (8): 1259. дои : 10.1080/0966813032000141105 . JSTOR 3594506 . S2CID 143667635 – через JSTOR.