Otford Palace

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (August 2023) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

Otford Palace, also known as the Archbishop's Palace, is in Otford, an English village and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent. The village is located on the River Darent, flowing north down its valley from its source on the North Downs.

Since 2019, the site has been cared for and restored by The Archbishop’s Palace Conservation Trust (APCT), on a 99-year lease from Sevenoaks District Council.[1]

History

[edit]Roman period

[edit]A fragment of a Chi Rho monogram painted on Roman wall-plaster, was recovered from the fill of a Norman drain filled in when the medieval Manor was enlarged by Archbishop Winchelsea early in the fourteenth century. This material came from the nearby Church Field Roman Villa and suggests that Otford was a site of Christian worship in Roman Britain.[2][3]

Saxon Days

[edit]The King of Mercia, Offa, fought the Kentish Saxons in 776 at the Battle of Otford. In 791 (or possibly in the preceding year) Offa gave lands at Otford to Christ Church Canterbury (the 'vill by the name of Otford').[4] This was a very significant gift. It meant that the Monastery of Christ Church Canterbury and subsequently the Archbishops of Canterbury became the Lords of the Manor of Otford. The size of this piece of land was not recorded, but further gifts of land were made in 820 and 821. The first, by Coenwulf, King of Mercia and in the following year by Ceolwulf I, his brother and successor, who donated to Otford lands bordering the East bank of the River Darent between Shoreham and today's Bat and Ball.[3] The second charter, in which Ceolwulf gives Wulfred, Archbishop of Canterbury, five plough lands consisting of two groups, one lying north-west of Kemsing and the other to the south-west, can be found in the British Museum.[5]

A large, moated manor house was built here and enlarged over the next 600 years by 52 subsequent archbishops.

Until 1537, the palace was one of the chain of houses belonging to the archbishops of Canterbury. In 1500, the Court Roll stated that Otford was, "one of the grandest houses in England".

High Middle Ages

[edit]The estate was granted lands from the Thames to the border of Sussex, thus increasing the importance and size of the manor. In 1086 (Domesday Survey), it had six water mills and a large Demesne farm, worked by serfs. Later their obligations gradually became monetary, and their lives and status improved.[3]

The manor was surrounded by a moat from early times. The island was enlarged three times, including that in Tudor times. The manor was enlarged by Archbishop Winchelsea (1294-1313), who died there. He constructed a magnificent chapel.

Otford manor became a regular home for the Archbishops, among several others in the diocese and possibly their most valuable possession. The Archbishop travelled with a large retinue according to a timetable.[3]

Archbishop Thomas Becket was a regular visitor there before his exile, and martyrdom in 1170. Becket's Well lies in the grounds of Castle House, 150 yards east of the Palace site.

Edward III spent Christmas there in 1348, during a sede vacante, when it was controlled by the crown.[3]

Palace of Archbishop Warham

[edit]

It appears from sporadic records that by the time of the accession of Henry VIII, Warham had begun the remodelling and extension of the medieval house.[6] In 1514, Archbishop Warham frustrated by the City Fathers at Canterbury to allow him to build a new palace there, commenced work in Otford. According to his friend Erasmus, "he left nothing of the first work, but only the walls of a hall and of a chapel."[7] He added the North, East and West Ranges around a great courtyard. The enlarged Palace predated that of Cardinal Wolsey at Hampton Court and was little larger in its extent. Visitors to the Palace included Erasmus (a good friend of William Warham), and Hans Holbein the Younger.

Warham received Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio here in July 1518, who was en route to London to confer the title cardinal a latere upon Wolsey. In May 1520, King Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon journeyed up the Darent Valley from Greenwich Palace with an enormous retinue and stayed overnight en route to the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

A survey (c. 1537) recorded that over the bridge is the forebay or forefront of the Galerye well edified and bilded of free stone with large oute caste of baywondows after an uniforme plan by all the Northe Part of the said mote, verye pleasunte to the prospects and view of the said sighte. The hall was invironed aboute with Galeries and Towers and Turrette of Stone and the Chappell embatiled and parte covered with leade.

However, in 1537, Henry VIII forced Archbishop Thomas Cranmer to surrender both Otford and Knole to the Crown.[6] Archbishop Cranmer's secretary Ralph Morrice was present in c 1543 stated: "I was by when Otteford and Knole was given him. My Lord Cranmer mynding to have retained Knole unto himself, saied, that it is too small a house for his Majestie. "Marye" (saied the King), "I had rather to have it than this house (meaning Otteford), for it standith of a better soile. This house standith lowe and is rewmatike like unto Croydon where I colde never be without sykeness. And as for Knole it standith on a sounde parfait holsome grounde. And if I should make myne abode here as I do suerlie minde to do nowe and then, I will lye at Knole and most of my house shall lye at Otteford." And so my this means bothe these houses were delivered upp unto the Kings hands, and as for Otteford, it is a notable greate and ample house, whose reparations yerlie stode my Lordew in more that wolde thinke."

Elizabeth I showed relatively little interest in the Palace. However, she did stay at Otford in 1559 during July and August.[6] The Sidney family became Hereditary Kerpers of the Palace under Elizabeth. They had a lease on the Little Park and long wanted to acquire the estate. Robert Sidney offered in 1596 to build a house at his charge where the Queen could dine, as she had under Sir Henry Sidney in July 1573. She eventually sold it to the Sidney Family in 1601 as she needed funds to feed her troops in Ireland. The Sidneys converted the Western side of the North Range into their private quarters. Viscount Lisle sold the property in 1618-19, having first disparked the Great Park.[6] His use of the buildings of the north range as a keepers house ensured their survival; whereas, the rest of the palace was demolished for its materials. The north range was abandoned probably around the middle of the eighteenth century.[6]

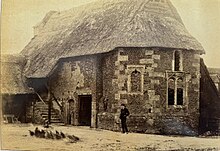

Farm buildings and after

[edit]The Great Park was divided into three farms. The northern farm became known as Place Great Lodge Farm, later Castle Farm. The Great North Range eventually became farm buildings. In the 18th century, the northern cloister was converted into a single story thatched-roof cowshed while the remains of the Gatehouse became a barn.

In 1761, the North East Tower of the Palace was demolished, and the stonework carried to Knole, Sevenoaks, where it was used to build Knole Folly which lies to the South-East of Knole House.

The principal surviving remains are the North-West Tower, the lower gallery, now converted to cottages, and a part of the Great Gatehouse. There are further remains on private land, and a section of the boundary wall can be seen in Bubblestone Road. The entire site, of about 4 acres (1.6 ha) is designated as an ancient monument.[8] There are many related buildings in the village, including a wall in St Bartholomew's Church dating from c. 1050.

Otford Palace today

[edit]Northwest Tower

[edit]The three-story corner towers have one high-status accommodation room on each floor. There is a stack of garderobes, one on each level. The flat leaded roof was accessible by the stair which ended in a small turret. The upper two rooms were panelled. The lowest story was plastered. Each chamber had a flat ceiling.[6]

Cloisters

[edit]

The Inner Courtyard was surrounded on three sides by Galleries. The Northern cloister with eleven now filled-in brick arches above a ragstone plinth is a small remnant and is the section between the Northwest Tower and the Gatehouse remnant. Some arches now contain modern windows. At first floor level there was originally a gallery with tiled roofs, and possibly with a timber frame. This formed a circuitous walkway with glazed windows, allowing exercise in poor weather or after dark and for discreet conversation. This was possibly England's first galleried house.[9] There do not appear to have been any original windows in the outer wall of the galleries.[6]

Gatehouse

[edit]

At the eastern end of the cottages is a large single-story building with a tiled roof and stone mullioned windows. This is the remains of the Western half of the Great Gatehouse. This great tower was probably five storeys, crenellated and crowned with flat lead-covered roofs. This was the grand entrance of Archbishop Warham's Palace. Above would have been an arch. At the southern end of the massive carved stone door jambs is still in position, attached to the inner end of the gatehouse wall. There was probably a second outer gate at the northern end, but there is no trace of this visible today.

The surviving ground floor on the western half of the Gatehouse was originally one large chamber with a porter's lodge to the front, with adjacent doors, one intact, the other with an enlarged though original rear arch.[6]

An external stair at the south end led to a two-room lodging on the first floor flanking a central room over the gate passage.[6] The gatehouse is late Gothic in its details.[6] The gatehouse was documented to have three roofs; therefore, there is likely to have been three storey sides with a single tall central room.[6] Cliff Ward in his guide to the palace, states that there may have been four or five storeys in the gatehouse.[3] The gatehouse was similar but less grand than those at Lambeth (1490) and Hampton Court.

Significance

[edit]Otford Palace is of exceptional significance for

• The evidence it provides for the form and architectural character of one of the outstanding buildings of early 16th century England.

• Its archaeological potential to yield much more information about that building, particularly on the moat island and its medieval predecessors.

Otford Palace is of considerable significance for

• The evidential value of the adaptation of the north-west range by the Sidney family.

• Its ability to illustrate the form and scale of a late medieval archiepiscopal palace, despite its fragmentary survival.

• The aesthetic qualities, designed and fortuitous, of the north range building in its open space setting.

• The contribution it makes to the character and appearance of Otford Conservation Area.

• The insight it provides into the character and ambition of Archbishop Warham.

Otford Palace is of some significance for

• As an illustration, especially with the archive material, of the struggle to conserve historic places during the 20th century.

• Its contribution to the identity of Otford and its community today.

The Palace is now under the care of the Archbishop's Palace Conservation Trust.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ "About The Trust – Archbishop's Palace Conservation Trust". Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "Chi Rho fragment – Archbishop's Palace Conservation Trust". Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f A Guided Walk Around Otford Palace by Cliff Ward. Copyright Otford and District Historical Society 2017 ISBN 978-0-9956479-2-3

- ^ Dunlop, John (1964). The Pleasant Town of Sevenoaks. Caxton and Holmesdale Press.

- ^ Ward, Gordon (1929). "The Making of the Great Park at Otford". Archaeologia Cantiana. 41: 1–12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l SAL Evening lecture - Invironed Aboute With Galeries and Towers': Archbishop Warham's Palace at Otford 11 February 2021 by Paul Drury FSA President of the Society of Antiquaries of London https://www.youtube.com/live/n8TEXMx2Brs?feature=share

- ^ Otford in Kent - A History. Dennis Clarke and Anthony Stoyel. Published by Otford and District Historical Society ISBN 0 9503963 0 3

- ^ Historic England. "Otford Palace". Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ A Guided Walk Around Otford Palace by Cliff Ward published by the Otford and District Historical Society 2017. ISBN 978-0-9956479-2-3

- ^ Archbishops Palace Conservation Trust (10 May 2022). "Archbishops Palace Conservation Trust".

External links

[edit]- "The Lost Palace of Henry VIII". Heritage Daily. Retrieved 18 March 2016.