Nordic folklore

Nordic folklore is the folklore of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland and the Faroe Islands. It has common roots with, and has been under mutual influence with, folklore in England, Germany, the Low Countries, the Baltic countries, Finland and Sápmi. Folklore is a concept encompassing expressive traditions of a particular culture or group. The peoples of Scandinavia are heterogenous, as are the oral genres and material culture that has been common in their lands. However, there are some commonalities across Scandinavian folkloric traditions, among them a common ground in elements from Norse mythology as well as Christian conceptions of the world.

Among the many tales common in Scandinavian oral traditions, some have become known beyond Scandinavian borders – examples include The Three Billy Goats Gruff and The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body.

Legends

[edit]- Tróndur was a powerful Viking chieftain who lived in the Faroe Islands during the 9th century. According to legend, Tróndur was killed by a Christian missionary named Sigmundur Brestisson, who had come to the islands to spread Christianity. Tróndur's legacy lives on in Faroese folklore, where he is often portrayed as a tragic hero.

- Risin and Kellingin are a pair of giants who are said to live on the island of Eysturoy. They are said to be very large and strong, and they are often depicted as being angry and destructive.[1][2]

- Skógafoss is a waterfall located in the south of Iceland, and is home to a number of folk tales, including one about hidden treasure that is said to be buried at the base of the waterfall by Þrasi Þórólfsson.[3]

- Reynisfjara is a black sand beach located in the south of Iceland. It is known for its towering basalt columns and its sea stacks.[4] The beach is also home to a number of folk tales, including one about a pair of trolls who were turned to stone by the sun.[5]

Traditions

[edit]- Grindadráp: This traditional whaling practice is deeply rooted in the cultural history and mythology of the Faroe Islands and has been a significant part of their way of life for centuries. The Grindadráp is associated with various customs, beliefs, and rituals, including the importance of communal cooperation and the sharing of resources.[6] However, the Grindadráp is also a contested and controversial practice in modern times, with concerns about its impact on animal welfare and sustainability.[7]

- Íslendingasögur (Icelandic Sagas or Sagas of Icelanders) are a series of prose narratives about events that took place in Iceland in the 9th, 10th and early 11th centuries.[8] They are mostly based on historical events, but they also contain elements of fiction. The sagas tell the stories of the early settlers of Iceland, their families, and their descendants.[9] Íslendingasögur are considered to be some of the finest examples of medieval literature.[10] The sagas were originally written down in the 13th and 14th centuries, but they are believed to have been passed down orally for many years before that.[11]

- Runes are part of the runic alphabet, used by various Germanic peoples, including the Norse.[12] In Nordic folklore, runes hold significant cultural and mystical importance.[13][14][15] They are often associated with the god Odin, who, according to myth, obtained the knowledge of runes through self-sacrifice.[12] Runes were used not only for writing but also in divination, magic, and as powerful symbols in Norse rituals, all together reflecting the interconnectedness of language, spirituality, and the mystical in Nordic folklore.[13] In modern Nordic culture, runes continue to hold symbolic and cultural significance.[16] While the runic alphabet is no longer in common use for writing, it has become a popular element in art, jewelry, and tattoos, often serving as a connection to Norse heritage and a way to express cultural pride.[17]

- Þorrablót is an annual mid-winter festival that celebrates traditional Icelandic cuisine. The festival is named after the month of Þorri, which falls in January or February, and features dishes such as fermented shark, dried fish, and smoked lamb.[18] The festival also includes music, dancing, and other cultural activities.[18]

Folk dances

[edit]Nordic folklore's traditional dances, intricately linked to celebrations, rituals, and communal assemblies, exhibit specific movements, patterns, and music deeply ingrained in the cultural fabric of the region. An exploration of these dances unveils insights into social dynamics, community cohesion, and the perpetuation of mythological themes across generations.

Norway

[edit]- The Norwegian folk dance, Halling, is characterized by its quick tempo (95–106 bpm) and features acrobatic moves. Typically performed by men during weddings or parties, Halling showcases athleticism through kicks, spins, and rhythmic footwork. The dance serves not only as a form of entertainment, but also as a display of skill and strength.[19][20]

Sweden

[edit]- Polska: Often danced as a couple, characterized by smooth flowing movements. Fiddle or nyckelharpa instruments are often found accompanying this dance. The dance holds cultural significance as it is commonly associated with celebrations and social gatherings.[21][22]

Faroe islands

[edit]- The Faroese Chain Dance is the national dance of the Faroe Islands, often accompanied by kvæði, the Faroese ballads. Dancers form a circle, holding hands, and move in a rhythmic and coordinated manner. These ballads may recount tales of legendary heroes, folklore figures, or historical events specific to the Faroe Islands. The combination of dance and music enhances the immersive experience, allowing participants to physically engage with the narratives.[23][24]

Folk Architecture

[edit]Norway

[edit]

Stave churches in Norway represent a unique synthesis of Christian and Norse cultural influences, evident in their architectural and ornamental features.[25] These wooden structures, characterized by intricate carvings, serve as tangible artifacts linking contemporary communities to historical narratives. Beyond mere historical relics, Stave churches function as active centers for cultural preservation, hosting various ceremonies and events. In the context of Norway's evolving cultural landscape, these churches endure as emblematic symbols of enduring identity and heritage, encapsulating the nuanced interplay between religious, mythological, and societal dimensions.[26]

Folklore figures

[edit]A large number of different mythological creatures from Scandinavian folklore have become well known in other parts of the world, mainly through popular culture and fantasy genres. Some of these are:

Trolls

[edit]

Troll (Norwegian and Swedish), trolde (Danish) is a designation for several types of human-like supernatural beings in Scandinavian folklore.[27] They are mentioned in the Edda (1220) as a monster with many heads.[28] Later, trolls became characters in fairy tales, legends and ballads.[29] They play a main part in many of the fairy tales from Asbjørnsen and Moes collections of Norwegian tales (1844).[30] Trolls may be compared to many supernatural beings in other cultures, for instance the Cyclopes of Homer's Odyssey.[citation needed] In Swedish, such beings are often termed 'jätte' (giant), a word related to the Norse 'jotun'. The origins of the word troll is uncertain.[31]

Trolls are described in many ways in Scandinavian folk literature, but they are often portrayed as stupid, and slow to act. In fairy tales and legends about trolls, the plot is often that a human with courage and presence of mind can outwit a troll. Sometimes saints' legends involve a holy man tricking an enormous troll to build a church. Trolls come in many different shapes and forms, and are generally not fair to behold, as they can have as many as nine heads. Trolls live throughout the land. They dwell in mountains, under bridges, and at the bottom of lakes. Trolls who live in the mountains may be rich and, hoarding mounds of gold and silver in their cliff dwellings. Dovregubben, a troll king, lives inside the Dovre Mountains with his court, as described in detail in Ibsen's Peer Gynt.

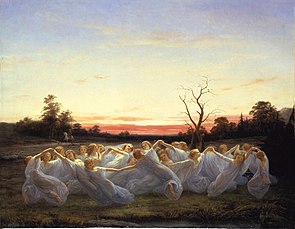

Elves

[edit]

Elves (in Swedish, Älva if female and Alv if male, Alv in Norwegian, and Elver in Danish) are in some parts mostly described as female (in contrast to the light and dark elves in the Edda), otherworldly, beautiful and seductive residents of forests, meadows and mires. They are skilled in magic and illusions. Sometimes they are described as small fairies, sometimes as full-sized women and sometimes as half transparent spirits, or a mix thereof. They are closely linked to the mist and it is often said in Sweden that, "the Elves are dancing in the mist". The female form of Elves may have originated from the female deities called Dís (singular) and Díser (plural) found in pre-Christian Scandinavian religion. They were very powerful spirits closely linked to the seid magic. Even today the word "dis" is a synonym for mist or very light rain in Swedish, Norwegian and Danish. Particularly in Denmark, the female elves have merged with the dangerous and seductive huldra, skogsfrun or "keeper of the forest", often called hylde. In some parts of Sweden the elves also share features with the Skogsfrun, "Huldra", or "Hylda", and can seduce and bewitch careless men and suck the life out of them or make them go down in the mire and drown. But at the same time the Skogsrå exists as its own being, with other distinct features clearly separating it from the elves. In more modern tales, it isn't uncommon for a rather ugly male Tomte, Troll, Vätte or a Dwarf to fall in love with a beautiful Elven female, as the beginning of a story of impossible or forbidden love.[32]

Huldra

[edit]The Huldra, Hylda, Skogsrå or Skogfru (Forest wife/woman) is a dangerous seductress who lives in the forest.[33] The Huldra is said to lure men with her charm. She has a long cow's tail, or according to some traditions, that of a fox, which she ties under her skirt in order to hide it from men.[33] If she can manage to get married in a church, her tail falls off and she becomes human.[citation needed]

Huldufolk

[edit]The Huldufólk are a race of fairies or elves who are said to live in the mountains, hills, and rocks of the Faroes. They are said to be similar in appearance to humans, but they are much smaller and have pale skin and long, dark hair. The huldufólk are generally benevolent creatures, but they can be mischievous if they are angered.[34]

Nattmara

[edit]In Scandinavia, there was the Nattmara. The Mara (or, in English, "nightmare") appears as a skinny young woman, dressed in a nightgown, with pale skin and long black hair and nails. After turning into sand, they could slip through the slimmest crack in the wood of a wall and terrorize the sleeping by "riding" on their chest, thus giving them nightmares. (This appears to describe "apparitions" commonly seen and/or felt during episodes of sleep paralysis.) The Mara traditionally rode on cattle, which would be left drained of energy and with tangled fur at the Mara's touch. Trees would curl up and wilt at the Mara's touch as well. In some tales, like the Banshee, they served as an omen of death. If one were to leave a dirty doll in a family living room, one of the members would soon fall ill and die of tuberculosis. ("Lung soot", another name for tuberculosis, referred to the effect of proper chimneys in 18th through 19th century homes. Inhabitants would therefore contract diseases due to inhaling smoke on a daily basis.)[35]

There was some discrepancy as to how they came into being. Some stories say that the Maras are restless children, whose souls leave their body at night to haunt the living. Another tale explains that if a pregnant woman pulled a horse placenta over her head before giving birth, the child would be delivered safely; however, if it were a son, he would become a werewolf, and if a daughter, a Mara. [citation needed]

Nøkken

[edit]

Nøkken, näcken, or strömkarlen, is a dangerous fresh water-dwelling creature. The nøkk plays a fiddle to lure his victims out onto thin ice on foot or onto water in leaky boats, then draws them down to the bottom of the water where he is waiting for them. The nøkk is also a shapeshifter, who usually changes into a horse or a man in order to lure victims to him.

Storsjöodjuret

[edit]Storsjöodjuret, often referred to as the "Great Lake Monster," is steeped in the folklore of Sweden, specifically with Lake Storsjön.[36] Notably the legendary creature was briefly granted a protected status by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, but this was later removed by the Swedish Parliament.[37]

Selma

[edit]Selma is a legendary sea serpent said to live in the 13-kilometre-long (8-mile) Lake Seljord (Seljordsvatnet) in Seljord, Vestfold og Telemark, Norway.[citation needed]

Circhos

[edit]The circhos is a sea creature that looks like a man with three toes on each foot.[38][39] Its skin is black and red. It has a long left foot and a small right foot which drags behind, making it lean left when walking.[40]

Kraken

[edit]The Kraken is a legendary sea-monster, resembling a giant octopus or squid said to appear off the coasts of Norway.[41]

Selkie

[edit]The Selkie is a mythical creature that is part-human and part-seal. According to legend, Selkies can shed their seal skins and transform into humans. There are many stories in Faroese folklore about Selkies falling in love with humans and leaving their sea life behind to live on land.[42]

Dreygur

[edit]The dreygur is a legendary creature from Faroese folklore. It is said to be a type of undead being that inhabits the mountains and hills of the Faroe Islands.[43] The dreygur is typically described as a large, strong creature with pale skin and long, dark hair. It is often depicted as being cannibalistic.[44]

Wights

[edit]

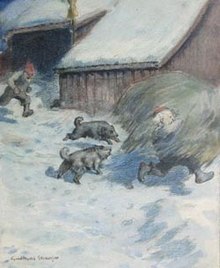

The Nisse (in southern Sweden, Norway and Denmark) or tomte (in Sweden) is a benevolent wight who takes care of the house and barn when the farmer is asleep, but only if the farmer reciprocates by setting out food for the nisse and he himself also takes care of his family, farm and animals. If the nisse is ignored or maltreated or the farm is not cared for, he is likely to sabotage the work instead to teach the farmer a lesson. Although the nisse should be treated with respect, some tales warn against treating him too kindly. There's a Swedish story in which a farmer and his wife entered their barn early in the morning and found a little, old, grey man sweeping the floor. They saw his clothing, which was nothing more than torn rags, and the wife decided to make him some new ones; when the nisse found them in the barn, however, he considered himself too elegant to perform any more farm labour and thus disappeared from the farm.[citation needed] Nisser are also associated with Christmas and the yule time. Farmers customarily place bowls of rice porridge on their doorsteps to please the nisser, comparative to the cookies and milk left out for Santa Claus in other cultures. Some believe that the nisse brings them presents as well.

In Swedish, the word "tomten" (definite form of "tomte") is very closely linked to the word for the plot of land where a house or cottage is built, which is called "tomten" as well (definite form of "tomt"). Therefore, some scholars believe that the wight Tomten originates from some sort of general house god or deity prior to Old Norse religion.[citation needed] A Nisse/Tomte is said to be able to change his size between that of a 5-year-old child and a thumb, and also to have the ability to make himself invisible.

A type of wight from Northern Sweden called Vittra lives underground, is invisible most of the time and has its own cattle. Most of the time Vittra are rather distant and do not meddle in human affairs, but are fearsome when enraged. This can be achieved by not respecting them properly, for example by neglecting to perform certain rituals (such as saying "look out" when putting out hot water or going to the toilet so they can move out of the way) or building your home too close to or, even worse, on top of their home, disturbing their cattle or blocking their roads. They can make your life very very miserable or even dangerous – they do whatever it takes to drive you away, even arrange accidents that will harm or even kill you. Even in modern days, people have rebuilt or moved houses in order not to block a "Vittra-way", or moved from houses that are deemed a "Vittra-place" (Vittra ställe) because of bad luck – although this is rather uncommon. In tales told in the north of Sweden, Vittra often take the place that trolls, tomte and vättar hold in the same stories told in other parts of the country. Vittra are believed to sometimes "borrow" cattle that later would be returned to the owner with the ability to give more milk as a sign of gratitude. This tradition is heavily influenced by the fact that it was developed during a time when people let their cattle graze on mountains or in the forest for long periods of the year.

See also

[edit]- Birgit Ridderstedt

- Danish folklore

- Henrik Ibsen's 1867 play Peer Gynt

- Huldufólk

- John Bauer (illustrator)

- Norse mythology

- Norske Folkeeventyr, a collection of Norwegian folktales

- Thunderstone (folklore)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hammershaimb, V. U.; Jakobsen, Jakob (1891). Faerosk anthologi. S.L. Mollers bogtrykkeri. OCLC 954234796.

- ^ "The giant and the witch". visitfaroeislands.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "The spectacular Skógafoss Waterfall in South-Iceland and the Legend of the Treasure Chest". Guide to Iceland. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Gudmundsson, Agust (2017). "The Glorious Geology of Iceland's Golden Circle". GeoGuide. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55152-4. ISBN 978-3-319-55151-7. ISSN 2364-6497. S2CID 134322667. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "The Eerie Folktales Behind Iceland's Natural Wonders". Travel. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Bulbeck, Chilla; Bowdler, Sandra (2008). "The Faroes Grindadráp or Pilot Whale Hunt: The Importance of Its 'Traditional' Status in Debates with Conservationists". Australian Archaeology (67): 53–60. ISSN 0312-2417. JSTOR 40288022.

- ^ Caputo-Nimbark, Roshni (2022). ""Orgy of Blood" vs "Getting Food on the Table": Negotiating Essentializing Discourses around the Faroese Grindadráp". Ethnologies. 44 (2): 177–202. doi:10.7202/1108118ar. ISSN 1481-5974.

- ^ "Njáls saga", The Icelandic Family Saga, Harvard University Press, pp. 291–307, 31 December 1967, doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674729292.c30, ISBN 9780674729292, archived from the original on 6 September 2023, retrieved 1 May 2023

- ^ Bredsdorff, Thomas (2001). Chaos & love: the philosophy of the Icelandic family sagas. Museum Tusculanum Press, University of Copenhagen. ISBN 87-7289-570-5. OCLC 47704862.

- ^ L., Byock, Jesse (28 April 2023). Feud in the Icelandic saga. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-34101-2. OCLC 1377666414.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jakobsson, Ármann; Jakobsson, Sverrir, eds. (17 February 2017). The Routledge Research Companion to the Medieval Icelandic Sagas. doi:10.4324/9781315613628. ISBN 9781315613628. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Odin's Discovery of the Runes". Norse Mythology for Smart People. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schuppener, Georg (30 December 2021), "The far-right use of Norse-Germanic mythology", The Germanic Tribes, the Gods and the German Far Right Today, London: Routledge, pp. 37–74, doi:10.4324/9781003206309-3, ISBN 978-1-003-20630-9, retrieved 26 January 2024

- ^ Willson, Kendra (23 December 2016). "Finland in the margins of the Viking world". Elore. 23 (2). doi:10.30666/elore.79275. ISSN 1456-3010.

- ^ Bogachev, Roman; Fedyunina, Inna; Melnikova, Julia; Koteneva, Inna; Kudryavtseva, Natalia (2 December 2021). "Symbolic Meanings Of Runes Within The Linguistic Worldview Of Ancient Germans". European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. European Publisher: 532–538. doi:10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.66.

- ^ Åhfeldt, Laila Kitzler (19 November 2021). "Rune Carvers in Military Campaigns". Viking. 84 (1). doi:10.5617/viking.9058. ISSN 2535-2660.

- ^ Bennett, Lisa; Wilkins, Kim (29 August 2019). "Viking tattoos of Instagram: Runes and contemporary identities". Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. 26 (5–6): 1301–1314. doi:10.1177/1354856519872413. ISSN 1354-8565.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trabskaya, Julia; Gordin, Valery; Tihonova, Diana (2015). "The Study of Gastronomic Festivals Based on Cultural Heritage". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2672622. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ Sandvik, O. M. (1935). "Norwegian Folk-Music and Its Connection with the Dance". Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. 2: 92–97. ISSN 0071-0563. JSTOR 4521070.

- ^ Fiskvik, Anne (2020). "Renegotiating Identity Markers in Contemporary Halling Practices". Dance Research Journal. 52 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1017/s0149767720000054. ISSN 0149-7677.

- ^ Kaminsky, David (2011). "Gender and Sexuality in the Polska: Swedish Couple Dancing and the Challenge of Egalitarian Flirtation". Ethnomusicology Forum. 20 (2): 123–152. doi:10.1080/17411912.2011.587244. ISSN 1741-1912.

- ^ Hoppu, Petri (2014). "The Polska: Featuring Swedish in Finland". Congress on Research in Dance Conference Proceedings. 2014: 99–105. doi:10.1017/cor.2014.13. ISSN 2049-1255.

- ^ Wylie, Jonathan; Margolin, David (31 December 1981). The Ring of Dancers. University of Pennsylvania Press. doi:10.9783/9781512809190. ISBN 978-1-5128-0919-0.

- ^ Árnadóttir, Tóta (19 November 2018), "II: 43 Chain Dancing", Handbook of Pre-Modern Nordic Memory Studies, De Gruyter, pp. 716–726, doi:10.1515/9783110431360-079, ISBN 978-3-11-043136-0, retrieved 25 January 2024

- ^ Aune, Petter; Sack, Ronald L.; Selberg, Arne (1983). "The Stave Churches of Norway". Scientific American. 249 (2): 96–105. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0883-96. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ Reed, Michael F. (23 September 2020). "Norwegian Stave Churches and their Pagan Antecedents". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne. 24 (2): 3–13. doi:10.7202/1071663ar. ISSN 1918-4778.

- ^ Guðmundsdóttir, Aðalheiður (1 October 2017). "Behind the cloak, between the lines: Trolls and the symbolism of their clothing in Old Norse tradition". European Journal of Scandinavian Studies. 47 (2): 327–350. doi:10.1515/ejss-2017-0022. ISSN 2191-9402.

- ^ Jakobsson, Ármann (2018), "Horror in the Medieval North: The Troll", The Palgrave Handbook to Horror Literature, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 33–43, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-97406-4_3, ISBN 978-3-319-97405-7, retrieved 26 January 2024

- ^ Primiano, Leonard Norman; Narvaez, Peter (1996). "The Good People: New Fairylore Essays". The Journal of American Folklore. 109 (431): 105. doi:10.2307/541728. ISSN 0021-8715. JSTOR 541728.

- ^ Esborg, Line (28 March 2022), "Treue und Wahrheit: Asbjørnsen and Moe and the Scientification of Folklore in Norway", Grimm Ripples: The Legacy of the Grimms’ Deutsche Sagen in Northern Europe, Brill, pp. 185–221, doi:10.1163/9789004511644_008, ISBN 978-90-04-51164-4, retrieved 26 January 2024

- ^ Lindow, John (28 April 2023). Swedish Legends and Folktales. University of California Press. doi:10.2307/jj.2430675. ISBN 978-0-520-31777-2.

- ^ Taylor, Lynda (24 September 2014). The cultural significance of elves in northern European balladry (phd thesis). University of Leeds.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Syndergaard, Larry E. (1972). "The Skogsrå of Folklore and Strindberg's The Crown Bride". Comparative Drama. 6 (4): 310–322. doi:10.1353/cdr.1972.0023. ISSN 1936-1637.

- ^ Maurer, Konrad (1860). Isländische Volkssagen der Gegenwart... (in German). J. C. Hinrichs. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Kooistra, Lorraine (15 May 2018). "Scandinavian Myths and Grimm's Tales in Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf". editions.covecollective.org. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Adsten, Anne (7 December 2018). "Storsjöodjuret - The Great Lake Monster". Adventure Sweden. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Holmes, George; Smith, Thomas Aneurin; Ward, Caroline (24 July 2017). "Fantastic beasts and why to conserve them: animals, magic and biodiversity conservation". Oryx. 52 (2): 231–239. doi:10.1017/s003060531700059x. ISSN 0030-6053.

- ^ "De piscibus". www.unicaen.fr. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "L'auctoritas de Thomas de Cantimpré en matière ichtyologique (Vincent de Beauvais, Albert le Grand, l'Hortus sanitatis)". Resrarchgate. Catherine Jacquemard. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Bane, Theresa (25 April 2016). Encyclopedia of Beasts and Monsters in Myth, Legend and Folklore. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9505-4. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Salvador, Rodrigo B.; Tomotani, Barbara M. (2014). "The Kraken: when myth encounters science". História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 21 (3): 971–994. doi:10.1590/S0104-59702014000300010. ISSN 0104-5970.

- ^ McEntire, Nancy Cassell (31 December 2010). "Supernatural Beings in the Far North: Folkore, Folk Belief, and the Selkie". Scottish Studies. 35: 120. doi:10.2218/ss.v35.2692. ISSN 2052-3629.

- ^ Langeslag, P.S. Seasons in the literatures of the medieval North. ISBN 978-1-78204-584-7. OCLC 1268190091.

- ^ Smith, Gregg A. (2008). The function of the living dead in medieval Norse and Celtic literature: death and desire. Mellen. ISBN 978-0-7734-5353-1. OCLC 220341788.

Sources

[edit]- Reidar Th. Christiansen (1964). Folktales of Norway

- Reimund Kvideland and Henning K. Sehmsdorf (1988). Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend University of Minnesota. ISBN 0-8166-1503-9

- Day, David (2003). The World of Tolkien: Mythological Sources of The Lord of the Rings ISBN 0-517-22317-1

- Wood, Edward J. (1868). Giants and Dwarfs Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. London: Folcroft Library.

- Thompson, Stith (1961). "Folklore Trends in Scandinavia" in Dorson, Richard M. Folklore Research around the World. Indiana University Press.

- Hopp, Zinken (1961). Norwegian Folklore Simplified. Trans. Toni Rambolt. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions.

- Craigie, William A. (1896). Scandinavian Folklore: Illustrations of the Traditional Beliefs of the Northern People Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. London: Alexander Garnder

- Rose, Carol (1996). Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins. New York: W.W. Norton & Company ISBN 0-87436-811-1

- Jones, Gwyn (1956). Scandinavian Legends and Folk-tales. New York: Oxford University

- Oliver, Alberto (24 June 2009). The Tomte and Other Scandinavian Folklore Creatures Archived 14 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Community of Sweden. Visit Sweden. Web. 4 May 2010.

- MacCulloch, J.A. (1948). The Celtic and Scandinavian Religions. Chicago: Academy Chicago

External links

[edit]- Norwegian folktales in English translation Archived 23 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Archive of Icelandic Folktales, catalogued according to the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index (in Icelandic)

- Digital collection of Norwegian Eventyr and Legends by the University of Oslo (In Norwegian)