Scrum (software development)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Software development |

|---|

Scrum is an agile team collaboration framework commonly used in software development and other industries.

Scrum prescribes for teams to break work into goals to be completed within time-boxed iterations, called sprints. Each sprint is no longer than one month and commonly lasts two weeks. The scrum team assesses progress in time-boxed, stand-up meetings of up to 15 minutes, called daily scrums. At the end of the sprint, the team holds two further meetings: one sprint review to demonstrate the work for stakeholders and solicit feedback, and one internal sprint retrospective. A person in charge of a scrum team is typically called a scrum master.[2]

Scrum's approach to product development involves bringing decision-making authority to an operational level.[3] Unlike a sequential approach to product development, scrum is an iterative and incremental framework for product development.[4] Scrum allows for continuous feedback and flexibility, requiring teams to self-organize by encouraging physical co-location or close online collaboration, and mandating frequent communication among all team members. The flexible and semi-unplanned approach of scrum is based in part on the notion of requirements volatility, that stakeholders will change their requirements as the project evolves.[5]

History[edit]

The use of the term scrum in software development came from a 1986 Harvard Business Review paper titled "The New New Product Development Game" by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka. Based on case studies from manufacturing firms in the automotive, photocopier, and printer industries, the authors outlined a new approach to product development for increased speed and flexibility. They called this the rugby approach, as the process involves a single cross-functional team operating across multiple overlapping phases, in which the team "tries to go the distance as a unit, passing the ball back and forth".[6] The authors later developed scrum in their book, The Knowledge Creating Company.[7]

In the early 1990s, Ken Schwaber used what would become scrum at his company, Advanced Development Methods. Jeff Sutherland, John Scumniotales, and Jeff McKenna developed a similar approach at Easel Corporation, referring to the approach with the term scrum.[8] Sutherland and Schwaber later worked together to integrate their ideas into a single framework, formally known as scrum. Schwaber and Sutherland tested scrum and continually improved it, leading to the publication of a research paper in 1995,[9] and the Manifesto for Agile Software Development in 2001.[10] Schwaber also collaborated with Babatunde Ogunnaike at DuPont Research Station and the University of Delaware to develop Scrum. Ogunnaike believed that software development projects could often fail when initial conditions change, if the product management was not rooted in empirical practice.[3]

In 2002, Schwaber with others founded the Scrum Alliance and set up the Certified Scrum accreditation series.[11] Schwaber left the Scrum Alliance in late 2009 and subsequently founded Scrum.org which oversees the parallel Professional Scrum accreditation series.[12] Since 2009, a public document called The Scrum Guide[13] has been published and updated by Schwaber and Sutherland. It has been revised 6 times, with the current version being November 2020.

Scrum team[edit]

A scrum team is organized into at least three categories of individuals: the product owner, developers, and the scrum master. The product owner liaises with stakeholders, those who have interest in the project's outcome, to communicate tasks and expectations with developers.[14] Developers in a scrum team organize work by themselves, with the facilitation of a scrum master.[15] Scrum teams, ideally, should abide by the five values of scrum: commitment, courage, focus, openness, and respect.[13]

Product owner[edit]

Each scrum team has one product owner.[16] The product owner focuses on the business side of product development and spends the majority of time liaising with stakeholders and the team. The role is intended to primarily represent the product's stakeholders, the voice of the customer, or the desires of a committee, and bears responsibility for the delivery of business results.[17][18][19][20] Product owners manage the product backlog, which is essentially the project's running to-do list, and are responsible for maximizing the value that a team delivers.[18] They do not dictate the technical solutions of a team but may instead attempt to seek consensus among team members.[21][22]

As the primary liaison of the scrum team towards stakeholders, product owners are responsible for communicating announcements, project definitions and progress, RIDAs (risks, impediments, dependencies, and assumptions), funding and scheduling changes, the product backlog, and project governance, among other responsibilities.[23][better source needed] Product owners can also cancel a sprint if necessary, without the input of team members.[13]

Developers[edit]

In scrum, the term developer or team member refers to anyone who plays a role in the development and support of the product and can include researchers, architects, designers, programmers, etc.[13][24]

Scrum master[edit]

Scrum is facilitated by a scrum master, whose role is to educate and coach teams about scrum theory and practice.[1] Scrum masters have differing roles and responsibilities from traditional team leads or project managers. Some scrum master responsibilities include coaching, objective setting, problem solving, oversight, planning, backlog management, and communication facilitation.[1] On the other hand, traditional project managers often have people management responsibilities, which a scrum master does not. Scrum teams do not involve project managers, so as to maximize self-organisation among developers.[25]

Workflow[edit]

Sprint[edit]

A sprint (also known as an iteration, timebox or design sprint) is a fixed period of time wherein team members work on a specific goal. Each sprint is normally between one week and one month, with two weeks being the most common.[3] Usually, daily meetings are held to discuss the progress of the project undertaken as well as difficulties faced by team members. The outcome of the sprint is a functional deliverable, or a product which has received some development in increments.

When a sprint is abnormally terminated, the next step is to conduct new sprint planning, where the reason for the termination is reviewed.

Each sprint starts with a sprint planning event in which a sprint goal is defined. Priorities for planned sprints are chosen out of the backlog. Each sprint ends with two events:[8]

- A sprint review (progress shown to stakeholders to elicit their feedback)

- A sprint retrospective (identify lessons and improvements for the next sprints)

Scrum emphasizes actionable output at the end of each sprint, which brings the developed product closer to market success.

Sprint planning[edit]

At the beginning of a sprint, the scrum team holds a sprint planning event to:

- Agree on the sprint goal, that is, what they intend to deliver by sprint end

- Identifying product backlog items that contribute towards this goal

- Form a sprint backlog by selecting which identified items should be completed in the sprint

The suggested maximum duration of sprint planning is eight hours for a four-week sprint.[13]

Daily scrum[edit]

Each day during a sprint, the developers hold a daily scrum (often conducted standing up) with specific guidelines, and which may be facilitated by a scrum master.[3][26] Daily scrum meetings are intended to be less than 15 minutes in length, taking place at the same time and location daily. The purpose of the meeting is to announce progress made towards the sprint goal and issues that may be hindering the goal, without going into any detailed discussion. Once over, individual members can go into a 'breakout session' or an 'after party' for extended discussion and collaboration.[27] Scrum masters are responsible for ensuring that team members use daily scrums effectively, or, if team members are unable to use them, to provide alternatives to achieve similar outcomes.[28][29]

Post-sprint events[edit]

Conducted at the end of a sprint, a sprint review is a meeting that has a team share the work they've completed with stakeholders and liaise with them on feedback, expectations, and upcoming plans. At a sprint review completed deliverables are demonstrated to stakeholders, who should also be made aware of product increments and works in progress. The recommended duration for a sprint review is one hours per week of sprint.[13]

A sprint retrospective is a separate meeting that allows team members to internally analyze strengths and weaknesses of the sprint, future areas of improvement, and continuous process improvement actions.[30]

Backlog refinement[edit]

Backlog refinement is a process by which team members revise and prioritize a backlog for future sprints.[31] It can be done as a separate stage done before the beginning of a new sprint or as a continuous process that team members work on by themselves. Backlog refinement can include the breaking down of large tasks into smaller and clearer ones, the clarification of success criteria, and the revision of changing priorities and returns. It is recommended to invest of up to 10 percent of a team's sprint capacity on backlog refinement.[13]

Artifacts[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

Artifacts are a means by which scrum teams manage product development by documenting work done towards the project. The main scrum artifacts used are the product backlog, sprint backlog, and increment.

Product backlog[edit]

The product backlog is a breakdown of work to be done and contains an ordered list of product requirements (such as features, bug fixes, non-functional requirements) that the team maintains for a product. The order of a product backlog corresponds to the urgency of the task. Common formats for backlog items include user stories and use cases.[25] The product backlog may also contain the product owner's assessment of business value and the team's assessment of the product's effort or complexity, which can be stated in story points using the rounded Fibonacci scale. These estimates help the product owner to gauge the timeline and may influence the ordering of product backlog items.[32]

The product owner maintains and prioritizes product backlog items based on considerations such as risk, business value, dependencies, size, and timing. High-priority items at the top of the backlog are broken down into more detail for developers to work on, while tasks further down the backlog may be more vague.[3]

Sprint backlog[edit]

The sprint backlog is the subset of items from the product backlog intended for developers to address in a particular sprint.[33] Developers fill this backlog with tasks they deem appropriate to fill the sprint, using past performance to assess their capacity for each sprint. The scrum approach has tasks on the sprint backlog not assigned to developers by any particular individual or leader. Team members self organize by pulling work as needed according to the backlog priority and their own capabilities and capacity.[34]

Increment[edit]

An increment is a potentially releasable output of a sprint, which meets the sprint goal. It is formed from all the completed sprint backlog items, integrated with the work of all previous sprints. An ideal increment is complete, fully functioning, and in a usable condition.

Other artifacts[edit]

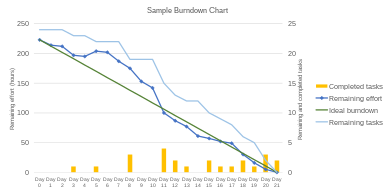

Burndown chart[edit]

Often used in scrum, a burndown chart is a publicly displayed chart showing remaining work.[35] Updated every day, it provides quick visualizations for reference. The horizontal axis of the burndown chart shows the days remaining, while the vertical axis shows the amount of work remaining each day. During sprint planning, the ideal burndown chart is plotted. Then, during the sprint, developers update the chart with remaining work so the chart is updated day by day, showing a comparison between actual and predicted.

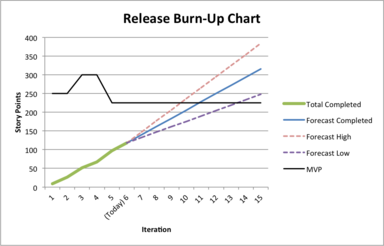

Release burn-up chart[edit]

Updated at the end of each sprint, the release burn-up chart shows progress towards delivering a forecast scope. The horizontal axis of the release burn-up chart shows the sprints in a release, while the vertical axis shows the amount of work completed at the end of each sprint.

Velocity[edit]

Some project managers believe that a team's total capability effort for a single sprint can be derived by evaluating work completed in the last sprint. The collection of historical "velocity" data is a guideline for assisting the team in understanding their capacity. Nonetheless, the concept of velocity has been controversial among scrum practitioners.

Limitations[edit]

Some have argued that scrum events, such as daily scrum and scrum review, hurt productivity and waste time that could be better spent on actual productive tasks.[36][37] In practice, many scrum practitioners conduct events, like the daily scrum, as an extended discussion, without complying with the time-boxing requirement.[citation needed]

Scrum has also been observed to pose difficulties for a number of types of teams, including those which are part-time or geographically distant; which have members that are highly specialized and would be better off working by themselves or in working cliques; which have many external dependencies that disrupt planned short sprints of work from occurring; and which are unsuitable for incremental and development testing.[38][39]

Adaptations[edit]

Scrum is frequently tailored or adapted in different contexts to achieve varying aims.[40] A common approach to adapting scrum is the combination of scrum with other software development methodologies, as scrum does not cover the whole product development lifecycle.[41] Various scrum practitioners have also suggested more detailed techniques for how to apply or adapt scrum to particular problems or organizations. Many refer to these techniques as 'patterns', an analogous use to design patterns in architecture and software.[42][43]

Scrumban[edit]

Scrumban is a software production model based on scrum and kanban. To illustrate each stage of work, teams working in the same space often use post-it notes or a large whiteboard.[44] Scrumban is especially suited for product maintenance with frequent and unexpected work items, such as production defects or programming errors. In such cases time-limited scrum sprints may not be as beneficial, although scrum's daily events and other practices can still be applied. At the same time, kanban models allow a team to visualize work stages and limitations.[45]

Scrum of scrums[edit]

Scrum of scrums is a technique to operate scrum at scale, for multiple teams coordinating on the same product. Scrum-of-scrums daily scrum meetings involve ambassadors selected from each individual team, who may be either a developer or scrum master. As a tool for coordination, scrum of scrums allows teams to collectively work on team-wide risks, impediments, dependencies, and assumptions (RIDAs), which may be tracked in a backlog of its own.[46][47]

Large-scale scrum[edit]

Large-scale scrum is a product development framework that scales scrum with varied rules and guidelines, developed by Bas Vodde and Craig Larman.[48][49] There are two levels to the framework: the first level, designed for up to eight teams; and the second level, known as 'LeSS Huge', which can accommodate development involving hundreds of developers.[50]

Criticism[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2024) |

A systematic review found "that Distributed Scrum has no impact, positive or negative on overall project success" in distributed software development.[51]

Martin Fowler, one of the authors of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, has criticised what he calls "faux-agile" practices that are "disregarding agile's values and principles",[52] and "the Agile Industrial Complex imposing methods upon people" contrary to the Agile principle of valuing "individuals and interactions over processes and tools"[10] and allowing the individuals doing the work to decide how the work is done, changing processes to suit their needs.

In September 2016, Ron Jeffries, a signatory to the Agile Manifesto,[10] described what he called "Dark Scrum", saying that "Scrum can be very unsafe for programmers."[53]

See also[edit]

- Agile software development

- Agile learning

- Disciplined agile delivery

- Comparison of scrum software

- High-performance teams

- Lean software development

- Project management

- Unified Process

Citations[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ken Schwaber; Jeff Sutherland. "The Scrum Guide" (PDF). Scrum.org. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ "What Is A Scrum Master? Everything You Need To Know – Forbes Advisor". www.forbes.com. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Schwaber, Ken (February 1, 2004). Agile Project Management with Scrum. Microsoft Press. ISBN 978-0-7356-1993-7.

- ^ "What is Scrum?". What is Scrum? An Agile Framework for Completing Complex Projects – Scrum Alliance. Scrum Alliance. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ J. Henry and S. Henry. Quantitative assessment of the software maintenance process and requirements volatility. In Proc. of the ACM Conference on Computer Science, pages 346–351, 1993.

- ^ Takeuchi, Hirotaka; Nonaka, Ikujiro (January 1, 1986). "The New New Product Development Game". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

Moving the Scrum Downfield

- ^ The Knowledge Creating Company. Oxford University Press. 1995. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-976233-0. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sutherland, Jeff (October 2004). "Agile Development: Lessons learned from the first Scrum". Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Sutherland, Jeffrey Victor; Schwaber, Ken (1995). Business object design and implementation: OOPSLA '95 workshop proceedings. The University of Michigan. p. 118. ISBN 978-3-540-76096-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Manifesto for Agile Software Development". Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Maximini, Dominik (January 8, 2015). The Scrum Culture: Introducing Agile Methods in Organizations. Management for Professionals. Cham: Springer (published 2015). p. 26. ISBN 978-3-319-11827-7. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland presented Scrum for the first time at the OOPSLA conference in Austin, Texas, in 1995. [...] In 2001, the first book about Scrum was published. [...] One year later (2002), Ken founded the Scrum Alliance, aiming at providing worldwide Scrum training and certification.

- ^ "Home". Scrum.org. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Sutherland, Jeff; Schwaber, Ken (2013). "Scrum Guides". ScrumGuides.org. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ Morris, David (2017). Scrum: an ideal framework for agile projects. In Easy Steps. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-1-84078-731-3. OCLC 951453155.

- ^ Cobb, Charles G. (2015). The Project Manager's Guide to Mastering Agile: Principles and Practices for an Adaptive Approach. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-118-99104-6.

- ^ Cohn, Mike (2010). Succeeding with Agile: Software Development Using Scrum. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-57936-2.

- ^ Rubin, Kenneth (2013), Essential Scrum. A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process, Addison-Wesley, p. 173, ISBN 978-0-13-704329-3

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGreal, Don; Jocham, Ralph (June 4, 2018). The Professional Product Owner: Leveraging Scrum as a Competitive Advantage. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 978-0-13-468665-3.

- ^ Pichler, Roman (March 11, 2010). Agile Product Management with Scrum: Creating Products that Customers Love. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 978-0-321-68413-4.

- ^ Ambler, Scott. "The Product Owner Role: A Stakeholder Proxy for Agile Teams". agilemodeling.com. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

[...] in practice there proves to be two critical aspects to this role: first as a stakeholder proxy within the development team and second as a project team representative to the overall stakeholder community as a whole.

- ^ "The Scrum Guide" (PDF). Scrum.org. p. 6. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Role of the Product Owner". Scrum Alliance. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "The Product Owner Role". Scrum Master Test Prep. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Rad, Nader K.; Turley, Frank (2018). Agile Scrum Foundation Courseware, Second Edition. 's-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands: Van Haren. p. 26. ISBN 978-94-018-0279-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pete Deemer; Gabrielle Benefield; Craig Larman; Bas Vodde (December 17, 2012). "The Scrum Primer: A Lightweight Guide to the Theory and Practice of Scrum (Version 2.0)". InfoQ.

- ^ "What is a Daily Scrum?". Scrum.org. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Flewelling, Paul (2018). The Agile Developer's Handbook: Get more value from your software development: get the best out of the Agile methodology. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-78728-020-5.

- ^ McKenna, Dave (2016). The Art of Scrum: How Scrum Masters Bind Dev Teams and Unleash Agility. Aliquippa, PA: CA Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4842-2276-8.

- ^ Drongelen, Mike van; Dennis, Adam; Garabedian, Richard; Gonzalez, Alberto; Krishnaswamy, Aravind (2017). Lean Mobile App Development: Apply Lean startup methodologies to develop successful iOS and Android apps. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-78646-704-1.

- ^ Rubin, Kenneth (2012), Essential Scrum. A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process, Addison-Wesley (published 2013), p. 375, ISBN 978-0-13-704329-3

- ^ Project Management Institute 2021, Glossary §3 Definitions.

- ^ Higgins, Tony (March 31, 2009). "Authoring Requirements in an Agile World". BA Times.

- ^ Russ J. Martinelli; Dragan Z. Milosevic (January 5, 2016). Project Management ToolBox: Tools and Techniques for the Practicing Project Manager. Wiley. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-118-97320-2.

- ^ Ken Schwaber; Jeff Sutherland. "The Scrum Guide" (PDF). Scrum.org. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Charles G. Cobb (January 27, 2015). The Project Manager's Guide to Mastering Agile: Principles and Practices for an Adaptive Approach. John Wiley & Sons. p. 378. ISBN 978-1-118-99104-6.

- ^ Jenson, John (March 8, 2019). "Meetings: The productivity killer for developers". TandemSeven – The Experience Innovation Company. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Not all developers like agile, and here are 5 reasons why". Business Matters. December 4, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Turk, Dan; France, Robert; Rumpe, Bernhard (2014) [2002]. "Limitations of Agile Software Processes". Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Extreme Programming and Flexible Processes in Software Engineering: 43–46. arXiv:1409.6600.

- ^ "Issues and Challenges in Scrum Implementation" (PDF). International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 3 (8). August 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Hron, Michal; Obwegeser, Nikolaus (January 1, 2022). "Why and how is Scrum being adapted in practice: A systematic review". Journal of Systems and Software. 183: 111110. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2021.111110. ISSN 0164-1212. S2CID 240950847.

- ^ Hron, M.; Obwegeser, N. (January 2018). "Scrum in practice: an overview of Scrum adaptations" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2018 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), January 3–6, 2018.

- ^ Bjørnvig, Gertrud; Coplien, Jim (June 21, 2008). "Scrum as Organizational Patterns". Gertrude & Cope.

- ^ "Scrum Pattern Community". ScrumPLoP.org. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ Ladas, Corey (October 27, 2007). "scrum-ban". Lean Software Engineering. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Kniberg, Henrik; Skarin, Mattias (December 21, 2009). "Kanban and Scrum – Making the most of both" (PDF). InfoQ. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "Risk Management – How to Stop Risks from Screwing Up Your Projects!". Kelly Waters.

- ^ "Scrum of Scrums". Agile Alliance. December 17, 2015. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ "Large-Scale Scrum (LeSS)". 2014.

- ^ Grgic (2015). "Descaling organisation with LeSS (Blog)".

- ^ Larman, Craig; Bas Vodde (May–June 2013). "Scaling Agile Development" (PDF). Crosstalk.

- ^ Santos, Ronnie de Souza; Ralph, Paul; Arshad, Arham; Stol, Klaas-Jan (October 5, 2023). "Distributed Scrum: A Case Meta-Analysis". ACM Computing Surveys. doi:10.1145/3626519. S2CID 263672588.

- ^ Fowler, Martin (August 25, 2018). "The State of Agile Software in 2018". martinfowler.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Jeffries, Ron (September 8, 2016). "Dark Scrum". ronjeffries.com. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

References[edit]

- Vacaniti, Daniel (February 2018). "The Kanban Guide for Scrum Teams" (PDF). scrum.org. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- Verheyen, Gunther (2013). Scrum – A Pocket Guide (A Smart Travel Companion) ISBN 978-90-8753-720-3.

- Münch, Jürgen; Armbrust, Ove; Soto, Martín; Kowalczyk, Martin (2012). Software Process Definition and Management. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-24291-5.

- A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK guide) (7th ed.). Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. 2021. ISBN 978-1-62825-664-2.

- Rubin, Kenneth (2013). Essential Scrum. A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process. Addison-Wesley. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-13-704329-3.

- Deemer, Pete; Benefield, Gabrielle; Larman, Craig; Vodde, Bas (2009). "The Scrum Primer". Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- Janoff, N.S.; Rising, L. (2000). "The Scrum Software Development Process for Small Teams" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 6, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.