Gematria

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Gematria (/ɡəˈmeɪtriə/; Hebrew: גמטריא or gimatria גימטריה, plural גמטראות or גימטריות, gimatriot)[1] is the practice of assigning a numerical value to a name, word or phrase by reading it as a number, or sometimes by using an alphanumerical cipher. The letters of the alphabets involved have standard numerical values, but a word can yield several values if a cipher is used.

According to Aristotle (384–322 BCE), isopsephy, based on the Milesian numbering of the Greek alphabet developed in the Greek city of Miletus, was part of the Pythagorean tradition, which originated in the 6th century BCE. The first evidence of use of Hebrew letters as numbers dates to 78 BCE; gematria is still used in Jewish culture. Similar systems have been used in other languages and cultures, derived from or inspired by either Greek isopsephy or Hebrew gematria, and include Arabic abjad numerals and English gematria.

The most common form of Hebrew gematria is used in the Talmud and Midrash,[2][3] and elaborately by many post-Talmudic commentators. It involves reading words and sentences as numbers, assigning numerical instead of phonetic value to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet. When read as numbers, they can be compared and contrasted with other words or phrases – cf. the Hebrew proverb נכנס יין יצא סוד (nichnas yayin yatza sod, lit. 'wine entered, secret went out', i.e. "in vino veritas"). The gematric value of יין ('wine') is 70 (י=10; י=10; ן=50) and this is also the gematric value of סוד ('secret', ס=60; ו=6; ד=4).[4]

Although a type of gematria system ('Aru') was employed by the ancient Babylonian culture, their writing script was logographic, and the numerical assignments they made were to whole words. Aru was very different from the Milesian systems used by Greek and Hebrew cultures, which used alphabetic writing scripts. The value of words with Aru were assigned in an entirely arbitrary manner and correspondences were made through tables,[5] and so cannot be considered a true form of gematria.

Gematria sums can involve single words, or a string of lengthy calculations. A short example of Hebrew numerology that uses gematria is the word חי (chai, lit. 'alive'), which is composed of two letters that (using the assignments in the mispar gadol table shown below) add up to 18. This has made 18 a "lucky number" among the Jewish people.

In early Jewish sources, the term can also refer to other forms of calculation or letter manipulation, for example atbash.[6]

Etymology

[edit]Classical scholars agree that the Hebrew word gematria was derived from the Greek word γεωμετρία geōmetriā, "geometry",[7] though some scholars believe it to derive from Greek γραμματεια grammateia "knowledge of writing".[citation needed] It is likely that both Greek words had an influence on the formation of the Hebrew word.[8][1] Some hold it to derive from the order of the Greek alphabet, gamma being the third letter of the Greek alphabet ("gamma tria").[7]

The word has been extant in English since at least the 17th century from translations of works by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. It is largely used in Jewish texts, notably in those associated with the Kabbalah. Neither the concept nor the term appears in the Hebrew Bible itself.[1]

History

[edit]The first documented use of gematria is from an Assyrian inscription dating to the 8th century BCE, commissioned by Sargon II. In this inscription, Sargon II states: "the king built the wall of Khorsabad 16,283 cubits long to correspond with the numerical value of his name."[9]

The practice of using alphabetic letters to represent numbers developed in the Greek city of Miletus, and is thus known as the Milesian system.[10] Early examples include vase graffiti dating to the 6th century BCE.[11] Aristotle wrote that the Pythgoraean tradition, founded in the 6th century BCE by Pythagoras of Samos, practiced isopsephy,[12] the Greek predecessor of gematria. Pythagoras was a contemporary of the philosophers Anaximander, Anaximenes, and the historian Hecataeus, all of whom lived in Miletus, across the sea from Samos.[13] The Milesian system was in common use by the reign of Alexander the Great (336–323 BCE) and was adopted by other cultures during the subsequent Hellenistic period.[10] It was officially adopted in Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (284–246 BCE).[10]

In early biblical texts, numbers were written out in full using Hebrew number words. The first evidence of the use of Hebrew letters as numerals appears during the late Hellenistic period, in 78 BCE.[14] Scholars have identified gematria in the Hebrew Bible,[15][16][17][18] the canon of which was fixed during the Hasmonean dynasty (c. 140 BCE to 37 BCE),[19] though some scholars argue it was not fixed until the second century CE or even later.[20] The Hasmonean king of Judea, Alexander Jannaeus (died 76 BCE) had coins inscribed in Aramaic with the Phoenician alphabet, marking the 20th and 25th years of his reign using the letters K and KE (למלכא אלכסנדרוס שנת כ and למלכא אלכסנדרוס שנת כה).[21]

Some old Mishnaic texts may preserve very early usage of this number system, but no surviving written documents exist, and some scholars believe these texts were passed down orally and during the early stages before the Bar Kochba rebellion were never written.[22] Gematria is not known to be found in the Dead Sea scrolls, a vast body of texts from 100 BCE – 100 CE, or in any of the documents found from the Bar-Kochba revolt circa 150 CE.

According to Proclus in his commentary on the Timaeus of Plato written in the 5th century, the author Theodorus Asaeus from a century earlier interpreted the word "soul" (ψυχή) based on gematria and an inspection of the graphical aspects of the letters that make up the word. According to Proclus, Theodorus learned these methods from the writings of Numenius of Apamea and Amelius. Proclus rejects these methods by appealing to the arguments against them put forth by the Neoplatonic philosopher Iamblichus. The first argument was that some letters have the same numerical value but opposite meaning. His second argument was that the form of letters changes over the years, and so their graphical qualities cannot hold any deeper meaning. Finally, he puts forth the third argument that when one uses all sorts of methods as addition, subtraction, division, multiplication, and even ratios, the infinite ways in which these can be combined allow virtually any number to be produced to suit any purpose.[23]

Some scholars propose that at least two cases of gematria appear in the New Testament. According to one theory, the reference to the miraculous "catch of 153 fish" in John 21:11 is an application of gematria derived from the name of the spring called 'EGLaIM in Ezekiel 47:10.[24][25][26] The appearance of this gematria in John 21:11 has been connected to one of the Dead Sea Scrolls, namely 4Q252, which also applies the same gematria of 153 derived from Ezekiel 47 to state that Noah arrived at Mount Ararat on the 153rd day after the beginning of the flood.[27] Some historians see gematria behind the reference to the number of the name of the Beast in Revelation as 666, which corresponds to the numerical value of the Hebrew transliteration of the Greek name "Neron Kaisar", referring to the 1st century Roman emperor who persecuted the early Christians.[28] Another possible influence on the use of 666 in Revelation goes back to reference to Solomon's intake of 666 talents of gold in 1 Kings 10:14.[29]

Gematria makes several appearances in various Christian and Jewish texts written in the first centuries of the common era. One appearance of gematria in the early Christian period is in the Epistle of Barnabas 9:6–7, which dates to sometime between 70 and 132 CE. There, the 318 servants of Abraham in Genesis 14:14 is used to indicate that Abraham looked forward to the coming of Jesus as the numerical value of some of the letters in the Greek name for Jesus as well as the 't' representing a symbol for the cross also equaled 318. Another example is a Christian interpolation in the Sibylline Oracles, where the symbolic significance of the value of 888 (equal to the numerical value of Iesous, the Latinized rendering of the Greek version of Jesus' name) is asserted.[30] Irenaeus also heavily criticized the interpretation of letters by the Gnostic Marcus. Because of their association with Gnosticism and the criticisms of Irenaeus as well as Hippolytus of Rome and Epiphanius of Salamis, this form of interpretation never became popular in Christianity[31]—though it does appear in at least some texts.[32] Another two examples can be found in 3 Baruch, a text that may have either been composed by a Jew or a Christian sometime between the 1st and 3rd centuries. In the first example, a snake is stated to consume a cubit of ocean every day, but is unable to ever finish consuming it, because the oceans are also refilled by 360 rivers. The number 360 is given because the numerical value of the Greek word for snake, δράκων, when transliterated to Hebrew (דרקון) is 360. In a second example, the number of giants stated to have died during the Deluge is 409,000. The Greek word for 'deluge', κατακλυσμός, has a numerical value of 409 when transliterated in Hebrew characters, thus leading the author of 3 Baruch to use it for the number of perished giants.[33]

Gematria is often used in Rabbinic literature. One example is that the numerical value of "The Satan" (השטן) in Hebrew is 364, and so it was said that the Satan had authority to prosecute Israel for 364 days before his reign ended on the Day of Atonement, an idea which appears in Yoma 20a and Peskita 7a.[30][34] Yoma 20a states: "Rami bar Ḥama said: The numerological value of the letters that constitute the word HaSatan is three hundred and sixty four: Heh has a value of five, sin has a value of three hundred, tet has a value of nine, and nun has a value of fifty. Three hundred and sixty-four days of the solar year, which is three hundred and sixty-five days long, Satan has license to prosecute."[35] Genesis 14:14 states that Abraham took 318 of his servants to help him rescue some of his kinsmen, which was taken in Peskita 70b to be a reference to Eleazar, whose name has a numerical value of 318.

The total value of the letters of the Islamic Basmala, i.e. the phrase Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim ("In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful"), according to the standard Abjadi system of numerology, is 786.[36] This number has therefore acquired a significance in folk Islam and Near Eastern folk magic and also appears in many instances of pop-culture, such as its appearance in the 2006 song '786 All is War' by the band Fun-Da-Mental.[36] A recommendation of reciting the basmala 786 times in sequence is recorded in Al-Buni. Sündermann (2006) reports that a contemporary "spiritual healer" from Syria recommends the recitation of the basmala 786 times over a cup of water, which is then to be ingested as medicine.[37] The use of gematria is still pervasive in many parts of Asia and Africa.[38]

Methods of Hebrew gematria

[edit]Standard encoding

[edit]In standard gematria (mispar hechrechi), each letter is given a numerical value between 1 and 400, as shown in the following table. In mispar gadol, the five final letters are given their own values, ranging from 500 to 900. It is possible that this well-known cipher was used to conceal other more hidden ciphers in Jewish texts. For instance, a scribe may discuss a sum using the 'standard gematria' cipher, but may intend the sum to be checked with a different secret cipher.[citation needed]

|

|

|

A mathematical formula for finding a letter's corresponding number in mispar gadol is:[citation needed]

where x is the position of the letter in the language letters index (regular order of letters), and the floor and modulo functions are used.

Vowels

[edit]The value of the Hebrew vowels is not usually counted, but some lesser-known methods include the vowels as well. The most common vowel values are as follows (a less common alternative value, based on the digit sum, is given in parentheses):

|

|

|

Sometimes, the names of the vowels are spelled out and their gematria is calculated using standard methods.[39]

Other methods

[edit]There are many different methods used to calculate the numerical value for the individual Hebrew/Aramaic words, phrases or whole sentences. Gematria is the 29th of 32 hermeneutical rules countenanced by the Rabbis of the Talmud for valid aggadic interpretation of the Torah.[40] More advanced methods are usually used for the most significant Biblical verses, prayers, names of God, etc. These methods include:[41]

- Mispar hechrachi (absolute value) is the standard method. It assigns the values 1–9, 10–90, 100–400 to the 22 Hebrew letters in order. Sometimes it is also called mispar ha-panim (face number), as opposed to the more complicated mispar ha-akhor (back number).

- Mispar gadol (large value) counts the final forms (sofit) of the Hebrew letters as a continuation of the numerical sequence for the alphabet, with the final letters assigned values from 500 to 900. The name mispar gadol is sometimes used for a different method, Otiyot beMilui.

- The same name, mispar gadol, is also used for another method, which spells the name of each letter and adds the standard values of the resulting string. For example, the letter aleph is spelled aleph lamed peh, giving it a value of .

- Mispar katan (small value) calculates the value of each letter, but truncates all of the zeros. It is also sometimes called mispar me'ugal.

- Mispar siduri (ordinal value) with each of the 22 letters given a value from 1 to 22.

- Mispar bone'eh (building value, also revu'a, square[42]) is calculated by walking over each letter from the beginning to the end, adding the value of all previous letters and the value of the current letter to the running total. Therefore, the value of the word achad (one) is .

- Mispar kidmi (preceding value) uses each letter as the sum of all the standard gematria letter values preceding it. Therefore, the value of aleph is 1, the value of bet is 1+2=3, the value of gimel is 1+2+3=6, etc. It is also known as mispar meshulash (triangular or tripled number).

- Mispar p'rati calculates the value of each letter as the square of its standard gematria value. Therefore, the value of aleph is 1 × 1 = 1, the value of bet is 2 × 2 = 4, the value of gimel is 3 × 3 = 9, etc. It is also known as mispar ha-merubah ha-prati.

- Mispar ha-merubah ha-klali is the square of the standard absolute value of each word.

- Mispar meshulash calculates the value of each letter as the cube of their standard value. The same term is more often used for mispar kidmi.

- Mispar ha-akhor – The value of each letter is its standard value multiplied by the position of the letter in a word or a phrase in either ascending or descending order. This method is particularly interesting, because the result is sensitive to the order of letters. It is also sometimes called mispar meshulash (triangular number).

- Mispar mispari spells out the standard values of each letter by their Hebrew names ("achad" (one) is etc.), and then adds up the standard values of the resulting string.

- Otiyot be-milui ("filled letters", also known as mispar gadol or mispar shemi), uses the value of each letter as equal to the value of its name.[43] For example, the value of the letter aleph is , bet is , etc. Sometimes the same operation is applied two or more times recursively. In a variation known as otiyot pnimiyot (inner letters), the initial letter in the spelled-out name is omitted, thus the value of aleph becomes 30+80=110.

- Mispar ne'elam (hidden number) spells out the name of each letter without the letter itself (e.g., "leph" for aleph) and adds up the value of the resulting string.

- Mispar katan mispari (integral reduced value) is used where the total numerical value of a word is reduced to a single digit. If the sum of the value exceeds 9, the integer values of the total are repeatedly added to produce a single-digit number. The same value will be arrived at regardless of whether it is the absolute values, the ordinal values, or the reduced values that are being counted by methods above. For example, the value of word emet (truth - אֶמֶת) is aleph + mem + tav: , Emet - Emet is , emet - emet - emet is , etc

- Mispar musafi adds the number of the letters in the word or phrase to their gematria.

- Kolel is the number of words, which is often added to the gematria. In case of one word, the standard value is incremented by one.

Related transformations

[edit]Within the wider topic of gematria are included the various alphabet transformations, where one letter is substituted by another based on a logical scheme:

- Atbash exchanges each letter in a word or a phrase by opposite letters. Opposite letters are determined by substituting the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet (aleph) with the last letter (tav), the second letter (bet) with the next to last (shin), etc. The result can be interpreted as a secret message or calculated by the standard gematria methods. A few instances of atbash are found already in the Hebrew Bible. For example, see Jeremiah 25:26, and 51:41, with Targum and Rashi, in which the name ששך ("Sheshek") is thought to represent בבל (Babylon).[1]

- Albam – the alphabet is divided in half, eleven letters in each section. The first letter of the first series is exchanged for the first letter of the second series, the second letter of the first series for the second letter of the second series, and so forth.

- Achbi divides the alphabet into two equal groups of 11 letters. Within each group, the first letter is replaced by the last, the second by the 10th, etc.

- Ayak bakar replaces each letter by another one that has a 10-times-greater value. The final letters usually signify the numbers from 500 to 900. Thousands is reduced to ones (1,000 becomes 1, 2,000 becomes 2, etc.)

- Ofanim replaces each letter by the last letter of its name (e.g. peh for aleph).

- Akhas beta divides the alphabet into three groups of 7, 7 and 8 letters. Each letter is replaced cyclically by the corresponding letter of the next group. The letter Tav remains the same.

- Avgad replaces each letter by the next one. Tav becomes aleph. The opposite operation is also used.

Most of the above-mentioned methods and ciphers are listed by Rabbi Moshe Cordevero.[44]

Some authors provide lists of as many as 231 various replacement ciphers, related to the 231 mystical Gates of the Sefer Yetzirah.[45]

Dozens of other far more advanced methods are used in Kabbalistic literature, without any particular names. In Ms. Oxford 1,822, one article lists 75 different forms of gematria.[46] Some known methods are recursive in nature and are reminiscent of graph theory or make a lot of use of combinatorics. Rabbi Elazar Rokeach (born c. 1176 – died 1238) often used multiplication, instead of addition, for the above-mentioned methods. For example, spelling out the letters of a word and then multiplying the squares of each letter value in the resulting string produces very large numbers, in orders of trillions. The spelling process can be applied recursively, until a certain pattern (e.g., all the letters of the word "Talmud") is found; the gematria of the resulting string is then calculated. The same author also used the sums of all possible unique letter combinations, which add up to the value of a given letter. For example, the letter Hei, which has the standard value of 5, can be produced by combining , , , , , or , which adds up to . Sometimes combinations of repeating letters are not allowed (e.g., is valid, but is not). The original letter itself can also be viewed as a valid combination.[45]

Variant spellings of some letters can be used to produce sets of different numbers, which can be added up or analyzed separately. Many various complex formal systems and recursive algorithms, based on graph-like structural analysis of the letter names and their relations to each other, modular arithmetic, pattern search and other highly advanced techniques, are found in the "Sefer ha-Malchut" by Rabbi David ha-Levi of the Draa Valley, a Spanish-Moroccan Kabbalist of the 15th–16th century.[39] Rabbi David ha-Levi's methods also consider the numerical values and other properties of the vowels.

Kabbalistic astrology uses some specific methods to determine the astrological influences on a particular person. According to one method, the gematria of the person's name is added to the gematria of his or her mother's name; the result is then divided by 7 and 12. The remainders signify a particular planet and Zodiac sign.[47]

Transliterated Hebrew

[edit]Historically, hermetic and esoteric groups of the 19th and 20th centuries in the UK and in France used a transliterated Hebrew cipher with the Latin alphabet. In particular, the transliterated cipher was taught to members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In 1887, S.L. MacGregor Mathers, who was one of the order's founders, published the transliterated cipher in The Kabbalah Unveiled in the Mathers table.[48][49]

| TABLE OF HEBREW AND CHALDEE LETTERS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Sound or Power | Hebrew and Chaldee Letters |

Numerical Values | Roman character by which expressed |

Names | Signification of Names | |||

| 1. | a (soft breathing). | א | 1. | (Thousands are denoted by a larger letter; thus an Aleph larger than the rest of the let- ters among which it is, signifies not 1, but 1000.) |

A. | Aleph. | Ox. | ||

| 2. | b, bh (v). | ב | 2. | B. | Beth. | House. | |||

| 3. | g (hard), gh. | ג | 3. | G. | Gimel. | Camel. | |||

| 4. | d, dh (flat th). | ד | 4. | D. | Daleth. | Door. | |||

| 5. | h (rough breathing). | ה | 5. | H. | He. | Window. | |||

| 6. | v, u, o. | ו | 6. | V. | Vau. | Peg, nail. | |||

| 7. | z, dz. | ז | 7. | Z. | Zayin. | Weapon, sword. | |||

| 8. | ch (guttural). | ח | 8. | CH. | Cheth. | Enclosure, fence. | |||

| 9. | t (strong). | ט | 9. | T. | Teth. | Serpent. | |||

| 10. | i, y (as in yes). | י | 10. | I. | Yod. | Hand. | |||

| 11. | k, kh. | כ | Final = | ך | 20. | Final = 500 | K. | Caph. | Palm of the hand. |

| 12. | l. | ל | 30. | L. | Lamed. | Ox-goad. | |||

| 13. | m. | מ | Final = | ם | 40. | Final = 600 | M. | Mem. | Water. |

| 14. | n. | נ | Final = | ן | 50. | Final = 700 | N. | Nun. | Fish. |

| 15. | s. | ס | 60. | S. | Samekh. | Prop, support. | |||

| 16. | O, aa, ng (gutt.). | ע | 70. | O. | Ayin. | Eye. | |||

| 17. | p, ph. | פ | Final = | ף | 80. | Final = 800 | P. | Pe. | Mouth. |

| 18. | ts, tz, j. | צ | Final = | ץ | 90. | Final = 900 | TZ. | Tzaddi. | Fishing-hook. |

| 19. | q, qh (guttur.). | ק | 100. | (The finals are not always considered as bearing an in- creased numeri- cal value.) |

Q. | Qoph. | Back of the head. | ||

| 20. | r. | ר | 200. | R. | Resh. | Head. | |||

| 21. | sh, s. | ש | 300. | SH. | Shin. | Tooth. | |||

| 22. | th, t. | ת | 400. | TH. | Tau. | Sign of the cross. | |||

As a former member of the Golden Dawn, Aleister Crowley used the transliterated cipher extensively in his writings[50] for his two magical orders the A∴A∴[51] and Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O).[52] Many other occult authors belonging to various esoteric groups have either mentioned the cipher or published it in their books, including Paul Foster Case of the Builders of the Adytum (B.O.T.A).[53]

Use in non-Semitic languages

[edit]Greek

[edit]According to Aristotle (384–322 BCE), isopsephy, an early Milesian system using the Greek alphabet, was part of the Pythagorean tradition, which originated in the 6th century BCE.[12]

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE) offers a discussion in the Cratylus, involving a view of words and names as referring (more or less accurately) to the "essential nature"[54] of a person or object and that this view may have influenced—and is central to—isopsephy.[55][56]

A sample of graffiti at Pompeii (destroyed under volcanic ash in 79 CE) reads "I love the girl whose name is phi mu epsilon (545)".[57]

Other examples of use in Greek come primarily from the Christian literature. Davies and Allison state that, unlike rabbinic sources, isopsephy is always explicitly stated as being used.[58]

Latin

[edit]

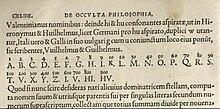

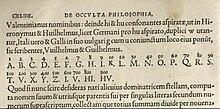

During the Renaissance, systems of gematria were devised for the Classical Latin alphabet. There were a number of variations of these which were popular in Europe.[59][60]

In 1525, Christoph Rudolff included a Classical Latin gematria in his work Nimble and beautiful calculation via the artful rules of algebra [which] are so commonly called "coss":

A=1 B=2 C=3 D=4 E=5 F=6 G=7 H=8 I=9 K=10 L=11 M=12

N=13 O=14 P=15 Q=16 R=17 S=18 T=19 U=20 W=21 X=22 Y=23 Z=24[59]

At the beginning of the Apocalypisis in Apocalypsin (1532), the German monk Michael Stifel (also known as Steifel) describes the natural order and trigonal number alphabets, claiming to have invented the latter. He used the trigonal alphabet to interpret the prophecy in the Biblical Book of Revelation, and predicted the world would end at 8am on October 19, 1533. The official Lutheran reaction to Steifel's prophecy shows that this type of activity was not welcome. Belief in the power of numbers was unacceptable in reformed circles, and gematria was not part of the reformation agenda.[59]: 44, 60 [61]

An analogue of the Greek system of isopsephy using the Latin alphabet appeared in 1583, in the works of the French poet Étienne Tabourot. This cipher and variations of it were published or referred to in the major work of Italian Pietro Bongo Numerorum Mysteria, and a 1651 work by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, and by Athanasius Kircher in 1665, and in a 1683 volume of Cabbalologia by Johann Henning, where it was simply referred to as the 1683 alphabet. It was mentioned in the work of Johann Christoph Männling The European Helicon or Muse Mountain, in 1704, and it was also called the Alphabetum Cabbalisticum Vulgare in Die verliebte und galante Welt by Christian Friedrich Hunold in 1707. It was used by Leo Tolstoy in his 1865 work War and Peace to identify Napoleon with the number of the Beast.[59][61]

English

[edit]English Qabalah refers to several different systems[62]: 24–25 of mysticism related to Hermetic Qabalah that interpret the letters of the English alphabet via an assigned set of numerological significances.[63][64]: 269 The first system of English gematria was used by the poet John Skelton in 1523 in his poem "The Garland of Laurel".[65]

The Agrippa code was used with English as well as Latin. It was defined by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in 1532, in his work De Occulta Philosopha. Agrippa based his system on the order of the Classical Latin alphabet using a ranked valuation as in isopsephy, appending the four additional letters in use at the time after Z, including J (600) and U (700), which were still considered letter variants.[66] Agrippa was the mentor of Welsh magician John Dee,[67] who makes reference to the Agrippa code in Theorem XVI of his 1564 book, Monas Hieroglyphica.[68]

Since the death of Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), a number of people have proposed numerical correspondences for English gematria in order to achieve a deeper understanding of Crowley's The Book of the Law (1904). One such system, the English Qaballa, was discovered by English magician James Lees on November 26, 1976.[69] The founding of Lees' magical order (O∴A∴A∴) in 1974 and his discovery of EQ are chronicled in All This and a Book by Cath Thompson.[70]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Solomon Schechter; Caspar Levias (1901–1906). "GEMAṬRIA". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Solomon Schechter; Caspar Levias (1901–1906). "GEMAṬRIA". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 95:3. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon. Volume II, London: The Soncino Press, 1983. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ^ Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:25. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon. Volume VII, London: The Soncino Press, 1983. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, tractate Sanhedrin 38a, see of Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2006), "'Etymythological Othering' and the Power of 'Lexical Engineering' in Judaism, Islam and Christianity. A Socio-Philo(sopho)logical Perspective", Explorations in the Sociology of Language and Religion, edited by Tope Omoniyi and Joshua A. Fishman, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 237–258.

- ^ LIEBERMAN, Stephen (1987). "A Mesopotamian Background for the So-Called Aggadic 'Measures' of Biblical Hermeneutics?". Hebrew Union College Annual. 58: 157–225. JSTOR 23508256.

- ^ "Sanhedrin 22a". Archived from the original on 2022-10-31. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ a b Klein, R. C. (2014). Lashon Hakodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew: a Linguistic Journey from Eden to Israel. Mosaica Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-937887-36-0.

- ^ "gematria". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Daniel Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, vol. 2, University of Chicago Press, 1927, pp. 43, 65.

- ^ a b c Halsey, W., ed. (1967). "Numerals and systems of numeration". Collier's Encyclopedia.

- ^ Jeffrey, L. (1961). The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Acevedo, J. (2020). Alphanumeric Cosmology from Greek Into Arabic: The Idea of Stoicheia Through the Medieval Mediterranean. Germany: Mohr Siebeck. p. 50. ISBN 978-3-16-159245-4.

- ^ Riedweg, Christoph (2005) [2002], Pythagoras: His Life, Teachings, and Influence, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-7452-1

- ^ Rosenstock, B. (2017). Transfinite Life: Oskar Goldberg and the Vitalist Imagination. Indiana University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-253-02997-3.

- ^ Knoh l, Israe l. "The Original Version of the Priestly Creation Account and the Religious Significance of the Number Eight in the Bible". Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ Knohl, Israel (2012). "Sacred Architecture: The Numerical Dimensions of Biblical Poems". Vetus Testamentum. 62 (#2): 189–19 7. doi:10.1163/156853312x629199. ISSN 0042-4935.

- ^ Hurowitz, Victor (2012). "Proverbs: Introduction and Commentary". Miqra LeYisrael. 1–2.

- ^ Lieberman, Stephen (1987). "A Mesopotamian Background for the So-Called Aggadic 'Measures' of Biblical Hermeneutics?". Hebrew Union College Annual: 157–225.

- ^ Davies, Philip R. (2001). "The Jewish Scriptural Canon in Cultural Perspective". In McDonald, Lee Martin; Sanders, James A. (eds.). The Canon Debate. Baker Academic. p. PT66. ISBN 978-1-4412-4163-4.

With many other scholars, I conclude that the fixing of a canonical list was almost certainly the achievement of the Hasmonean dynasty.

- ^ McDonald & Sanders, The Canon Debate, 2002, p. 5, cited are Neusner's Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine, pp. 128–145, and Midrash in Context: Exegesis in Formative Judaism, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Rosenstock, B. (2017). Transfinite Life: Oskar Goldberg and the Vitalist Imagination. New Jewish Philosophy and Thought. Indiana University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-253-03016-0. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ The invention of the ban against writing oral Torah Archived 2022-01-13 at the Wayback Machine, Yair Furstenberg, AJS Review, submitted 2022

- ^ Tzahi Weiss, Sefer Yeṣirah and its Contexts, Pennsylvania 2018, 26–28.

- ^ "Ezekiel 47 / Hebrew – English Bible / Mechon-Mamre". mechon-mamre.org. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Richard Bauckham, "The 153 Fish and the Unity of the Fourth Gospel", Neotestamentica 2002.

- ^ Mark Kiley, "Three More Fish Stories (John 21:11)", Journal of Biblical Literature 2008

- ^ George Brooke. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the New Testament. Fortress Press 2005, pp286-97

- ^ Craig Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Yale University Press, 2014, pg. 598

- ^ Bodner & Strawn, "Solomon and 666 (Revelation 13.18)", New Testament Studies (2020), pp. 299–312.

- ^ a b This and several other examples of the appearance of gematria are given in D.S. Russell. "Countdown: Arithmetic and Anagram in Early Biblical Interpretation". Expository Times 1993.

- ^ Tzahi Weiss, Sefer Yeṣirah and its Contexts, Pennsylvania 2018, 21–26, 28.

- ^ Tzahi Weiss, Sefer Yeṣirah and its Contexts, Pennsylvania 2018, 28–29.

- ^ Gideon Bohak. Greek-Hebrew Gematria in 3 Baruch and in Revelation. Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 1990.

- ^ trugman (2013-05-05). "Small Vessels". Ohr Chadash. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ The given text of Yoma 20a is from the William Davidson translation.

- ^ a b Shah & Haleem (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies, Oxford University Press, 2020, pp581, 587–88

- ^ Katja Sündermann, Spirituelle Heiler im modernen Syrien: Berufsbild und Selbstverständnis – Wissen und Praxis, Hans Schiler, 2006, p. 371 Archived 2022-10-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kravel-Tovi & D. Moore, Taking Stock: Cultures of Enumeration in Contemporary Jewish Life, The Modern Jewish Experience (Indiana University Press, 2016), 32, 71; Holt, Culture and Politics in Indonesia (Equinox Publishing, 2007), 81; Leslie & Young, Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge, Comparative Studies of Health Systems and Medical Care (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 261.

- ^ a b Sefer ha-Malchut, "Sifrei Chaim", Jerusalem, 2008

- ^ Pessin, Sarah (2013). A Readers Guide to Judaism. New York: Routledge. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-57958-139-8.

- ^ Moshe Cordovero, Pardes Rimmonim Archived 2019-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Toras Menachem – Tiferes Levi Yitzchok Vol. I – Bereshis, p. 2, fn. 7

- ^ the spelling of the name of the number comes from the Talmud

- ^ Moshe Cordevero, Sefer Pardes ha-Rimonim, שער האותיות

- ^ a b Elazar Rokeach, Sefer ha-Shem

- ^ Encyclopedia Judaica Vol. 7, 2007, p. 426

- ^ Commentary to Sefer Yetzirah, attributed to Saadia Gaon, 6:4; Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Sefer Yetzirah, "WeiserBooks", Boston, 1997, pp. 220–221

- ^ Mathers, S.L. MacGregor (1887). The Kabbalah Unveiled. London: Redway. p. 3.

- ^ Westcott, W. Wynn (1890). Numbers. London: Theosophical Publishing Society. p. 37.

- ^ See, for example, Crowley, Aleister (1977). "Sepher Sephiroth". 777 and other Qabalistic writings of Aleister Crowley. Maine: Samuel Weiser, INC. p. Preface. ISBN 0-87728-670-1.

- ^ Churton, Tobias (2011). Aleister Crowley: The Biography, Spiritual Revolutionary Romantic Explorer Occult Master - and spy. London: Watkins Publishing. pp. 47, 217. ISBN 978-1-78028-012-7.

- ^ DuQuette, Lon Milo (2001). The Chicken Qabalah of Rabbi Lamed Ben Clifford. York, Maine: Weiser Books. p. 404. ISBN 978-1-57863-215-2.

- ^ Fortune, Dion (1935). The Mystical Qabalah. London: Williams and Norgate Ltd. p. Forward.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Cratylus, by Plato". www.gutenberg.org. April 27, 2022. Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- ^ Marc Hirshman, Theology and exegesis in midrashic literature, in Jon Whitman, Interpretation and allegory: antiquity to the modern period. Brill, 2003. pp. 113–114.

- ^ John Michell, The Dimensions of Paradise: Sacred Geometry, Ancient Science, and the Heavenly Order on Earth, 2008. pp.59–65 ff.

- ^ Adela Yarbro Collins, Cosmology and Eschatology in Jewish and Christian Apocalypticism, Brill 2000, p116.

- ^ * Davies, William David; Allison, Dale C. (2004). A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 164.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c d Tatlow, Ruth. Bach and the Riddle of the Number Alphabet. Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg. 130-133. ISBN 0-521-36191-5

- ^ Ramsey, David (1997). "Bach and Numerology: "Dry Mathematical Stuff"?". Literature and Aesthetics. 7: 157–161. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ a b Dudley, Underwood. Numerology, Or, What Pythagoras Wrought. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-88385-524-0

- ^ Nema (1995). Maat Magick: A Guide to Self-Initiation. York Beach, Maine: Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-827-5.

- ^ Hulse, David Allen (2000). The Western Mysteries: An Encyclopedic Guide to the Sacred Languages and Magickal Systems of the World. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 1-56718-429-4.

- ^ Rabinovitch, Shelley; Lewis, James (2004). The Encyclopedia of Modern Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-2407-3.

- ^ Walker, Julia. M. Medusa's Mirrors: Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, and the metamorphosis of the female self, pp. 33–42 University of Delaware Press, 1998. ISBN 0-87413-625-3

- ^ Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius (1993). Tyson, Donald (ed.). Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Translated by James Freake. Llewellyn Publications. pp. Book II, Ch. 22. ISBN 978-0-87542-832-1.

- ^ Mostofizadeh, Kambiz (2012). Magic as Science and Religion: John Dee and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa Paperback. Mikazuki.

- ^ Dee, John (1975). The Hieroglyphic Monad. Translated by J. W. Hamilton-Jones. Weiser Books. ISBN 1-57863-203-X.

- ^ Thompson, Cath (2016). "Preliminaries". The Magickal Language of the Book of the Law: An English Qaballa Primer. Hadean Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-907881-68-8.

- ^ Thompson, Cath (2018). All This and a Book. Hadean Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-907881-78-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Clawson, Calvin C. (1999). Mathematical Mysteries: The Beauty and Magic of Numbers. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7382-0259-4.

- Menninger, Karl (1969). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13040-0.