Ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of land or water, and contain characteristic, geographically distinct assemblages of natural communities and species. The biodiversity of flora, fauna and ecosystems that characterise an ecoregion tends to be distinct from that of other ecoregions. In theory, biodiversity or conservation ecoregions are relatively large areas of land or water where the probability of encountering different species and communities at any given point remains relatively constant, within an acceptable range of variation (largely undefined at this point). Ecoregions are also known as "ecozones" ("ecological zones"), although that term may also refer to biogeographic realms.

Three caveats are appropriate for all bio-geographic mapping approaches. Firstly, no single bio-geographic framework is optimal for all taxa. Ecoregions reflect the best compromise for as many taxa as possible. Secondly, ecoregion boundaries rarely form abrupt edges; rather, ecotones and mosaic habitats bound them. Thirdly, most ecoregions contain habitats that differ from their assigned biome. Biogeographic provinces may originate due to various barriers, including physical (plate tectonics, topographic highs), climatic (latitudinal variation, seasonal range) and ocean chemical related (salinity, oxygen levels).

History

[edit]The history of the term is somewhat vague, and it had been used in many contexts: forest classifications (Loucks, 1962), biome classifications (Bailey, 1976, 2014), biogeographic classifications (WWF/Global 200 scheme of Olson & Dinerstein, 1998), etc.[1][2][3][4][5]

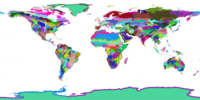

The phrase "ecological region" was widely used throughout the 20th century by biologists and zoologists to define specific geographic areas in research. In the early 1970s the term 'ecoregion' was introduced (short for ecological region), and R.G. Bailey published the first comprehensive map of U.S. ecoregions in 1976.[6] The term was used widely in scholarly literature in the 1980s and 1990s, and in 2001 scientists at the U.S. conservation organization World Wildlife Fund (WWF) codified and published the first global-scale map of Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World (TEOW), led by D. Olsen, E. Dinerstein, E. Wikramanayake, and N. Burgess.[7] While the two approaches are related, the Bailey ecoregions (nested in four levels) give more importance to ecological criteria and climate zones, while the WWF ecoregions give more importance to biogeography, that is, the distribution of distinct species assemblages.[8]

The TEOW framework originally delineated 867 terrestrial ecoregions nested into 14 major biomes, contained with the world's 8 major biogeographical realms. Subsequent regional papers by the co-authors covering Africa, Indo-Pacific, and Latin America differentiate between ecoregions and bioregions, referring to the latter as "geographic clusters of ecoregions that may span several habitat types, but have strong biogeographic affinities, particularly at taxonomic levels higher than the species level (genus, family)".[9][10][11] The specific goal of the authors was to support global biodiversity conservation by providing a "fourfold increase in resolution over that of the 198 biotic provinces of Dasmann (1974) and the 193 units of Udvardy (1975)." In 2007, a comparable set of Marine Ecoregions of the World (MEOW) was published, led by M. Spalding,[12] and in 2008 a set of Freshwater Ecoregions of the World (FEOW) was published, led by R. Abell.[13]

The concept of ecoregion applied by Bailey gives more importance to ecological criteria and climate, while the WWF concept gives more importance to biogeography, that is, the distribution of distinct species assemblages.[4]

In 2017, an updated version of the terrestrial ecoregions dataset was released in the paper "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm" led by E. Dinerstein with 48 co-authors.[14] Using recent advances in satellite imagery the ecoregion perimeters were refined and the total number reduced to 846 (and later 844), which can be explored on a web application developed by Resolve and Google Earth Engine.[15]

Definition and categorization

[edit]

An ecoregion is a "recurring pattern of ecosystems associated with characteristic combinations of soil and landform that characterise that region".[16] Omernik (2004) elaborates on this by defining ecoregions as: "areas within which there is spatial coincidence in characteristics of geographical phenomena associated with differences in the quality, health, and integrity of ecosystems".[17] "Characteristics of geographical phenomena" may include geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, hydrology, terrestrial and aquatic fauna, and soils, and may or may not include the impacts of human activity (e.g. land use patterns, vegetation changes). There is significant, but not absolute, spatial correlation among these characteristics, making the delineation of ecoregions an imperfect science. Another complication is that environmental conditions across an ecoregion boundary may change very gradually, e.g. the prairie-forest transition in the midwestern United States, making it difficult to identify an exact dividing boundary. Such transition zones are called ecotones.

Ecoregions can be categorized using an algorithmic approach or a holistic, "weight-of-evidence" approach where the importance of various factors may vary. An example of the algorithmic approach is Robert Bailey's work for the U.S. Forest Service, which uses a hierarchical classification that first divides land areas into very large regions based on climatic factors, and subdivides these regions, based first on dominant potential vegetation, and then by geomorphology and soil characteristics. The weight-of-evidence approach is exemplified by James Omernik's work for the United States Environmental Protection Agency, subsequently adopted (with modification) for North America by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

The intended purpose of ecoregion delineation may affect the method used. For example, the WWF ecoregions were developed to aid in biodiversity conservation planning, and place a greater emphasis than the Omernik or Bailey systems on floral and faunal differences between regions. The WWF classification defines an ecoregion as:

A large area of land or water that contains a geographically distinct assemblage of natural communities that:

- (a) Share a large majority of their species and ecological dynamics;

- (b) Share similar environmental conditions, and;

- (c) Interact ecologically in ways that are critical for their long-term persistence.

According to WWF, the boundaries of an ecoregion approximate the original extent of the natural communities prior to any major recent disruptions or changes. WWF has identified 867 terrestrial ecoregions, and approximately 450 freshwater ecoregions across the Earth.

Importance

[edit]The use of the term ecoregion is an outgrowth of a surge of interest in ecosystems and their functioning. In particular, there is awareness of issues relating to spatial scale in the study and management of landscapes. It is widely recognized that interlinked ecosystems combine to form a whole that is "greater than the sum of its parts". There are many attempts to respond to ecosystems in an integrated way to achieve "multi-functional" landscapes, and various interest groups from agricultural researchers to conservationists are using the "ecoregion" as a unit of analysis.

The "Global 200" is the list of ecoregions identified by WWF as priorities for conservation.

Terrestrial

[edit]

Terrestrial ecoregions are land ecoregions, as distinct from freshwater and marine ecoregions. In this context, terrestrial is used to mean "of land" (soil and rock), rather than the more general sense "of Earth" (which includes land and oceans).

WWF (World Wildlife Fund) ecologists currently divide the land surface of the Earth into eight biogeographical realms containing 867 smaller terrestrial ecoregions (see list). The WWF effort is a synthesis of many previous efforts to define and classify ecoregions.[18]

The eight realms follow the major floral and faunal boundaries, identified by botanists and zoologists, that separate the world's major plant and animal communities. Realm boundaries generally follow continental boundaries, or major barriers to plant and animal distribution, like the Himalayas and the Sahara. The boundaries of ecoregions are often not as decisive or well recognized, and are subject to greater disagreement.

Ecoregions are classified by biome type, which are the major global plant communities determined by rainfall and climate. Forests, grasslands (including savanna and shrubland), and deserts (including xeric shrublands) are distinguished by climate (tropical and subtropical vs. temperate and boreal climates) and, for forests, by whether the trees are predominantly conifers (gymnosperms), or whether they are predominantly broadleaf (Angiosperms) and mixed (broadleaf and conifer). Biome types like Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub; tundra; and mangroves host very distinct ecological communities, and are recognized as distinct biome types[clarification needed] as well.

Marine

[edit]

Marine ecoregions are: "Areas of relatively homogeneous species composition, clearly distinct from adjacent systems….In ecological terms, these are strongly cohesive units, sufficiently large to encompass ecological or life history processes for most sedentary species."[20] They have been defined by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to aid in conservation activities for marine ecosystems. Forty-three priority marine ecoregions were delineated as part of WWF's Global 200 efforts.[21] The scheme used to designate and classify marine ecoregions is analogous to that used for terrestrial ecoregions. Major habitat types are identified: polar, temperate shelves and seas, temperate upwelling, tropical upwelling, tropical coral, pelagic (trades and westerlies), abyssal, and hadal (ocean trench). These correspond to the terrestrial biomes.

The Global 200 classification of marine ecoregions is not developed to the same level of detail and comprehensiveness as that of the terrestrial ecoregions; only the priority conservation areas are listed.

See Global 200 Marine ecoregions for a full list of marine ecoregions.[22]

In 2007, TNC and WWF refined and expanded this scheme to provide a system of comprehensive near shore (to 200 meters depth) Marine Ecoregions of the World (MEOW).[22] The 232 individual marine ecoregions are grouped into 62 marine provinces, which in turn group into 12 marine realms, which represent the broad latitudinal divisions of polar, temperate, and tropical seas, with subdivisions based on ocean basins (except for the southern hemisphere temperate oceans, which are based on continents).

Major marine biogeographic realms, analogous to the eight terrestrial biogeographic realms, represent large regions of the ocean basins: Arctic, Temperate Northern Atlantic, Temperate Northern Pacific, Tropical Atlantic, Western Indo-Pacific, Central Indo-Pacific, Eastern Indo-Pacific, Tropical Eastern Pacific, Temperate South America, Temperate Southern Africa, Temperate Australasia, and Southern Ocean.[20]

A similar system of identifying areas of the oceans for conservation purposes is the system of large marine ecosystems (LMEs), developed by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Freshwater

[edit]

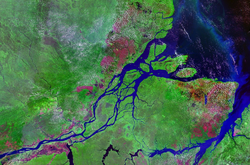

A freshwater ecoregion is a large area encompassing one or more freshwater systems that contains a distinct assemblage of natural freshwater communities and species. The freshwater species, dynamics, and environmental conditions within a given ecoregion are more similar to each other than to those of surrounding ecoregions and together form a conservation unit. Freshwater systems include rivers, streams, lakes, and wetlands. Freshwater ecoregions are distinct from terrestrial ecoregions, which identify biotic communities of the land, and marine ecoregions, which are biotic communities of the oceans.[23]

A map of Freshwater Ecoregions of the World, released in 2008, has 426 ecoregions covering virtually the entire non-marine surface of the earth.[24]

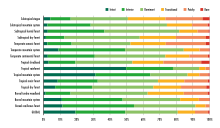

World Wildlife Fund (WWF) identifies twelve major habitat types of freshwater ecoregions: Large lakes, large river deltas, polar freshwaters, montane freshwaters, temperate coastal rivers, temperate floodplain rivers and wetlands, temperate upland rivers, tropical and subtropical coastal rivers, tropical and subtropical floodplain rivers and wetlands, tropical and subtropical upland rivers, xeric freshwaters and endorheic basins, and oceanic islands. The freshwater major habitat types reflect groupings of ecoregions with similar biological, chemical, and physical characteristics and are roughly equivalent to biomes for terrestrial systems.

The Global 200, a set of ecoregions identified by WWF whose conservation would achieve the goal of saving a broad diversity of the Earth's ecosystems, includes a number of areas highlighted for their freshwater biodiversity values. The Global 200 preceded Freshwater Ecoregions of the World and incorporated information from regional freshwater ecoregional assessments that had been completed at that time.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Loucks, O. L. (1962). A forest classification for the Maritime Provinces. Proceedings of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science, 25(Part 2), 85-167.

- ^ Bailey, R. G. 1976. Ecoregions of the United States (map). Ogden, Utah: USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Region. 1:7,500,000.

- ^ Bailey, R. G. 2002. Ecoregion-based design for sustainability. New York: Springer, [1].

- ^ a b Bailey, R. G. 2014. Ecoregions: The Ecosystem Geography of the. Oceans and Continents. 2nd ed., Springer, 180 pp., [2].

- ^ Olson, D. M. & E. Dinerstein (1998). The Global 200: A representation approach to conserving the Earth's most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biol. 12:502–515.

- ^ Bailey, R. G. 1976. Ecoregions of the United States (map). Ogden, Utah: USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Region. 1:7,500,000.

- ^ David M. Olson, Eric Dinerstein, Eric D. Wikramanayake, Neil D. Burgess, George V. N. Powell, Emma C. Underwood, Jennifer A. D'amico, Illanga Itoua, Holly E. Strand, John C. Morrison, Colby J. Loucks, Thomas F. Allnutt, Taylor H. Ricketts, Yumiko Kura, John F. Lamoreux, Wesley W. Wettengel, Prashant Hedao, Kenneth R. Kassem (November 1, 2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11) – via Oxford Academic.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bailey, R. G. 2014. Ecoregions: The Ecosystem Geography of the. Oceans and Continents. 2nd ed., Springer, 180 pp., [3].

- ^ Burgess, N.D.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Dinerstein, E.; et al. (2004). Terrestrial eco-regions of Africa and Madagascar: A conservation assessment. Washington DC.: Island Press [4]

- ^ Wikramanayake, Eric; Eric Dinerstein; Colby J. Loucks; et al. (2002). Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a Conservation Assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press

- ^ Dinerstein, E., Olson, D. Graham, D.J. et al. (1995). A Conservation Assessment of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank, Washington DC., [5].

- ^ Mark D. Spalding, Helen E. Fox, Gerald R. Allen, Nick Davidson, Zach A. Ferdaña, Max Finlayson, Benjamin S. Halpern, Miguel A. Jorge, Al Lombana, Sara A. Lourie, Kirsten D. Martin, Edmund McManus, Jennifer Molnar, Cheri A. Recchia, James Robertson (July 1, 2007). "Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas". BioScience. 57 (7) – via Oxford Academic.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robin Abell, Michele L. Thieme, Carmen Revenga, Mark Bryer, Maurice Kottelat, Nina Bogutskaya, Brian Coad, Nick Mandrak, Salvador Contreras Balderas, William Bussing, Melanie L. J. Stiassny, Paul Skelton, Gerald R. Allen, Peter Unmack, Alexander Naseka, Rebecca Ng, Nikolai Sindorf, James Robertson, Eric Armijo, Jonathan V. Higgins, Thomas J. Heibel, Eric Wikramanayake, David Olson, Hugo L. López, Roberto E. Reis, John G. Lundberg, Mark H. Sabaj Pérez, Paulo Petry (May 1, 2008). "Freshwater Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Biogeographic Units for Freshwater Biodiversity Conservation". BioScience. 58 (5): 403–414. doi:10.1641/B580507 – via Oxford Academic.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dinerstein, Eric (5 April 2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6) – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Dinerstein (Ed.), Eric (2017). "Ecoregions 2017". Ecoregions 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brunckhorst, D. (2000). Bioregional planning: resource management beyond the new millennium. Harwood Academic Publishers: Sydney, Australia.

- ^ Omernik, J. M. (2004). "Perspectives on the Nature and Definition of Ecological Regions". Environmental Management. 34 Suppl 1 (1): 34 – Supplement 1, pp.27–38. Bibcode:2004EnMan..34S..27O. doi:10.1007/s00267-003-5197-2. PMID 16044553. S2CID 11191859.

- ^ "Biomes - Conserving Biomes - WWF".

- ^ The State of the World's Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people – In brief. Rome: FAO & UNEP. 2020. doi:10.4060/ca8985en. ISBN 978-92-5-132707-4. S2CID 241416114.

- ^ a b Spalding, Mark D.; Fox, Helen E.; Allen, Gerald R.; Davidson, Nick; et al. (2007). "Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas". Bioscience Vol. 57 No. 7, July/August 2007, pp. 573–583. 57 (7): 573–583. doi:10.1641/B570707. S2CID 29150840.

- ^ Olson and Dinerstein 1998 and 2002

- ^ a b "Marine Ecoregions of the World". World Wide Fund for Nature.

- ^ Hermoso, Virgilio; Abell, Robin; Linke, Simon; Boon, Philip (2016). "The role of protected areas for freshwater biodiversity conservation: challenges and opportunities in a rapidly changing world". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 26 (s1): 3–10. doi:10.1002/aqc.2681. S2CID 88786689.

- ^ "Freshwater Ecoregions of the World". WWF.

Bibliography

[edit]Sources related to the WWC scheme:

- Main papers:

- Abell, R., M. Thieme, C. Revenga, M. Bryer, M. Kottelat, N. Bogutskaya, B. Coad, N. Mandrak, S. Contreras-Balderas, W. Bussing, M. L. J. Stiassny, P. Skelton, G. R. Allen, P. Unmack, A. Naseka, R. Ng, N. Sindorf, J. Robertson, E. Armijo, J. Higgins, T. J. Heibel, E. Wikramanayake, D. Olson, H. L. Lopez, R. E. d. Reis, J. G. Lundberg, M. H. Sabaj Perez, and P. Petry. (2008). Freshwater ecoregions of the world: A new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. BioScience 58:403–414, [6].

- Olson, D. M., Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E. D., Burgess, N. D., Powell, G. V. N., Underwood, E. C., D'Amico, J. A., Itoua, I., Strand, H. E., Morrison, J. C., Loucks, C. J., Allnutt, T. F., Ricketts, T. H., Kura, Y., Lamoreux, J. F., Wettengel, W. W., Hedao, P., Kassem, K. R. (2001). Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51(11):933–938, [7].

- Spalding, M. D. et al. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience 57: 573–583, [8].

- Africa:

- Burgess, N., J.D. Hales, E. Underwood, and E. Dinerstein (2004). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment. Island Press, Washington, D.C., [9].

- Thieme, M.L., R. Abell, M.L.J. Stiassny, P. Skelton, B. Lehner, G.G. Teugels, E. Dinerstein, A.K. Toham, N. Burgess & D. Olson. 2005. Freshwater ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A conservation assessment. Washington DC: WWF, [10].

- Latin America

- Dinerstein, E., Olson, D. Graham, D.J. et al. (1995). A Conservation Assessment of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank, Washington DC., [11].

- Olson, D. M., E. Dinerstein, G. Cintron, and P. Iolster. 1996. A conservation assessment of mangrove ecosystems of Latin America and the Caribbean. Final report for The Ford Foundation. World Wildlife Fund, Washington, D.C.

- Olson, D. M., B. Chernoff, G. Burgess, I. Davidson, P. Canevari, E. Dinerstein, G. Castro, V. Morisset, R. Abell, and E. Toledo. 1997. Freshwater biodiversity of Latin America and the Caribbean: a conservation assessment. Draft report. World Wildlife Fund-U.S., Wetlands International, Biodiversity Support Program, and United States Agency for International Development, Washington, D.C., [12].

- North America

- Russia and Indo-Pacific

- Krever, V., Dinerstein, E., Olson, D. and Williams, L. 1994. Conserving Russia's Biological Diversity: an analytical framework and initial investment portfolio. WWF, Switzerland.

- Wikramanayake, E., E. Dinerstein, C. J. Loucks, D. M. Olson, J. Morrison, J. L. Lamoreux, M. McKnight, and P. Hedao. 2002. Terrestrial ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a conservation assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA, [15].

Others:

- Brunckhorst, D. 2000. Bioregional planning: resource management beyond the new millennium. Harwood Academic Publishers: Sydney, Australia.

- Busch, D.E. and J.C. Trexler. eds. 2003. Monitoring Ecosystems: Interdisciplinary approaches for evaluating ecoregional initiatives. Island Press. 447 pages.

External links

[edit]- WWF WildFinder (interactive on-line map of ecoregions with additional information about animal species)

- WWF Map of the ecozones at the Wayback Machine (archived April 10, 2010), Original web page

- Activist network cultivating Ecoregions/Bioregions

- Sierra Club – ecoregions at the Wayback Machine (archived November 14, 2008), Original web page

- World Map of Ecoregions