Israeli cuisine

Israeli cuisine primarily comprises dishes brought from the Jewish diaspora, and has more recently been defined by the development of a notable fusion cuisine characterized by the mixing of Jewish cuisine and Arab cuisine.[1] It also blends together the culinary traditions of the various diaspora groups, namely those of Middle Eastern Jews with roots in Southwest Asia and North Africa, Sephardi Jews from Iberia, and Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe.[1][2]

The country's cuisine also incorporates food and drinks traditionally included in other Middle Eastern cuisines (e.g., Iranian cuisine from Persian Jews and Turkish cuisine from Turkish Jews) as well as in Mediterranean cuisines, such that spices like za'atar and foods such as falafel, hummus, msabbaha, shakshouka, and couscous are now widely popular in Israel.[3][4] However, the identification of Arab dishes as Israeli has led to accusations of cultural appropriation against Israel by Palestinians and other Arabs.[5][6]

Other influences on the cuisine are the availability of foods common to the Mediterranean, especially certain kinds of fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and fish; the tradition of observing kashrut; and food customs and traditions (minhag) specific to Shabbat and other Jewish holidays. Examples of these foods include challah, jachnun, malawach, gefilte fish, hamin, me'orav yerushalmi, and sufganiyot.

New dishes based on agricultural products such as oranges, avocados, dairy products, and fish, and others based on world trends have been introduced over the years, and chefs trained abroad have brought in elements of other international cuisines.[7]

History

Origins

Israel's culinary traditions comprise foods and cooking methods that span 3000 years of history. Over that time, these traditions have been shaped by influences from Asia, Africa and Europe, and religious and ethnic influences have resulted in a culinary melting pot. Biblical and archaeological records provide insight into the culinary life of the region as far back as 1000 years BCE.[8]

Ancient Israelite cuisine was based on several products that still play important roles in modern Israeli cuisine. These were known as the seven species: olives, figs, dates, pomegranates, wheat, barley and grapes.[9] The diet, based on locally grown produce, was enhanced by imported spices, readily available due to the country's position at the crossroads of east–west trade routes.[8]

During the Second Temple period (516 BCE–70 CE), Hellenistic and Roman culture heavily influenced cuisine, particularly of the priests and aristocracy of Jerusalem. Elaborate meals were served that included piquant entrées and alcoholic drinks, fish, beef, meat, pickled and fresh vegetables, olives, and tart or sweet fruits.[8]

After the destruction of the Second Temple and the exile of the majority of Jews from the Land of Israel, Jewish cuisine continued to develop in the many countries where Jewish communities have existed since Late Antiquity, influenced by the economics, agriculture, and culinary traditions of those countries.[citation needed]

Old Yishuv

The Old Yishuv was the Jewish community that lived in Ottoman Syria prior to the Zionist Aliyah from the diaspora that began in 1881. The cooking style of the community was Sephardi cuisine, which developed among the Jews of Spain before their expulsion in 1492, and in the areas to which they migrated thereafter, particularly the Balkans and Ottoman Empire. Sephardim and Ashkenazim also established communities in the Old Yishuv. Particularly in Jerusalem, they continued to develop their culinary style, influenced by Ottoman cuisine, creating a style that became known as Jerusalem Sephardi cuisine.[10] This cuisine included pies like sambousak, pastels and burekas, vegetable gratins and stuffed vegetables, and rice and bulgur pilafs, which are now considered to be Jerusalem classics.[7]

Groups of Hasidic Jews from Eastern Europe also began establishing communities in the late 18th century, and brought with them their traditional Ashkenazi cuisine, developing, however, distinct local variations, notably a peppery, caramelized noodle pudding known as kugel yerushalmi.[11]

Jewish immigration

Beginning with the First Aliyah in 1881, Jews began immigrating to the area from Yemen and Eastern Europe in larger numbers, particularly from Poland and Russia. These Zionist pioneers were motivated both ideologically and by the Mediterranean climate to reject the Ashkenazi cooking styles they grew up with, and adapt by using local produce, especially vegetables such as zucchini, peppers, eggplant, artichoke and chickpeas.[7] The first Hebrew cookbook, written by Erna Meyer, and published in the early 1930s by the Palestine Federation of the Women's International Zionist Organization, exhorted cooks to use Mediterranean herbs and Middle-Eastern spices and local vegetables in their cooking.[10] The bread, olives, cheese and raw vegetables they adopted became the basis for the kibbutz breakfast, which in more abundant forms is served in Israeli hotels, and in various forms in most Israeli homes today.[7][10]

Early years of the State

The State of Israel faced enormous military and economic challenges in its early years, and the period from 1948 to 1958 was a time of food rationing and austerity, known as tzena. In this decade, over one million Jewish immigrants, mainly from Arab countries, but also including European Holocaust survivors, inundated the new state. They arrived when only basic foods were available and ethnic dishes had to be modified with a range of mock or simulated foods, such as chopped "liver" from eggplant, and turkey as a substitute for veal schnitzel for Ashkenazim, kubbeh made from frozen fish instead of ground meat for Iraqi Jews, and turkey in place of the lamb kebabs of the Mizrahi Jews. These adaptations remain a legacy of that time.[7][10]

Substitutes, such as the wheat-based rice substitute, ptitim, were introduced, and versatile vegetables such as eggplant were used as alternatives to meat. Additional flavor and nutrition were provided from inexpensive canned tomato paste and puree, hummus, tahina, and mayonnaise in tubes. Meat was scarce, and it was not until the late 1950s that herds of beef cattle were introduced into the agricultural economy.[12]

Khubeza, a local variety of the mallow plant, became an important food source during the War of Independence. During the siege of Jerusalem, when convoys of food could not reach the city, Jerusalemites went out to the fields to pick khubeza leaves, which are high in iron and vitamins.[13] Instructions for cooking it broadcast by Jerusalem-based radio station Kol Hamagen, were picked up in Jordan, which convinced the Arabs that the Jews were dying of starvation and victory was at hand.[14] In the past decade, food writers in Israel have encouraged the population to prepare khubeza on Israel Independence Day.[15] Local chefs have begun to serve khubeza and other wild plants gathered from the fields in upscale restaurants.[16] The dish from the independence war is called ktzitzot khubeza and is still eaten by Israelis today.[citation needed]

Impact of immigration

Immigrants to Israel have introduced elements of the cuisines of the cultures and countries from whence they came.[1] In the nearly 50 years before 1948, there were successive waves of Jewish immigration, which brought a whole range of foods and cooking styles. Immigrants arriving from central Europe brought foods such as schnitzel and strudels, while Russian Jews brought borscht and herring dishes, such as schmaltz herring and vorschmack (gehakte herring).[7]

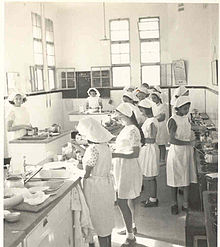

Ashkenazi dishes include chicken soup, schnitzel, lox, chopped liver, gefilte fish, knishes, kishka and kugel. The first Israeli patisseries were opened by Ashkenazi Jews, who popularized cakes and pastries from central and Eastern Europe, such as yeast cakes (babka), nut spirals (schnecken), chocolate rolls and layered pastries. After 1948, the greatest impact came from the large migration of Jews from Turkey, Iraq, Kurdistan and Yemen, and Mizrahi Jews from North Africa, particularly Morocco. Typically, the staff of army kitchens, schools, hospitals, hotels and restaurant kitchens has consisted of Mizrahi, Kurdish and Yemenite Jews, and this has had an influence on the cooking fashions and ingredients of the country.[7]

Mizrahi cuisine, the cuisine of Jews from North Africa, features grilled meats, sweet and savory puff pastries, rice dishes, stuffed vegetables, pita breads and salads, and shares many similarities with Arab cuisine. Other North African dishes popular in Israel include couscous, shakshouka, matbucha, carrot salad and chraime (slices of fish cooked in a spicy tomato sauce).

Sephardic dishes, with Balkan and Turkish influences incorporated in Israeli cuisine include burekas, yogurt and taramosalata. Yemenite Jewish foods include jachnun, malawach, skhug and kubane. Iraqi dishes popular in Israel include amba, various types of kubba, stuffed vegetables (mhasha), kebab, sambusac, sabich and pickled vegetables (hamutzim).

Modern trends

As Israeli agriculture developed and new kinds of fruits and vegetables appeared on the market, cooks and chefs began to experiment and devise new dishes with them.[12] They also began using "biblical" ingredients such as honey, figs, and pomegranates, and indigenous foods such as prickly pears (tzabar) and chickpeas. Since the late 1970s, there has been an increased interest in international cuisine, cooking with wine and herbs, and vegetarianism.[7]

A more sophisticated food culture in Israel began to develop when cookbooks, such as From the Kitchen with Love by Ruth Sirkis, published in 1974, introduced international cooking trends, and together with the opening of restaurants serving cuisines such as Chinese, Italian and French, encouraged more dining out.[10][17]

The 1980s were a formative decade: the increased optimism after the signing of the peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, the economic recovery of the mid-1980s and the increasing travel abroad by average citizens were factors contributing to a greater interest in food and wine. In addition, high-quality, locally produced ingredients became increasingly available. For example, privately owned dairies began to produce handmade cheeses from goat, sheep and cow's milk, which quickly became very popular both among chefs and the general public. In 1983, the Golan Heights Winery was the first of many new Israeli winemakers to help transform tastes with their production of world-class, semi-dry and dry wines. New attention was paid to the making of handmade breads and the production of high quality olive oil. The successful development of aquaculture ensured a steady supply of fresh fish, and the agricultural revolution in Israel led to an overwhelming choice and quality of fresh fruit, vegetables and herbs.[10]

Ethnic heritage cooking, both Sephardic and Ashkenazi, has made a comeback with the growing acceptance of the heterogeneous society. Apart from home cooking, many ethnic foods are now available in street markets, supermarkets and restaurants, or are served at weddings and bar mitzvahs, and people increasingly eat foods from ethnic backgrounds other than their own. Overlap and combinations of foods from different ethnic groups is becoming standard as a multi-ethnic food culture develops.[7][10]

The 1990s saw an increasing interest in international cuisines. Sushi, in particular, has taken hold as a popular style for eating out and as an entrée for events. In restaurants, fusion cuisine, with the melding of classic cuisines such as French and Japanese with local ingredients has become widespread. [citation needed]

In the 2000s, the trend of "eating healthy" with an emphasis on organic and whole-grain foods has become prominent, and medical research has led many Israelis to re-embrace the Mediterranean diet, with its touted health benefits.[18]

Characteristics

Geography has a large influence on Israeli cuisine, and foods common in the Mediterranean region, such as olives, wheat, chickpeas, dairy products, fish, and vegetables such as tomatoes, eggplants, and zucchini are prominent in Israeli cuisine. Fresh fruits and vegetables are plentiful in Israel and are cooked and served in many ways.[19]

There are various climatic areas in Israel and areas it has settled that allow a variety of products to be grown. Citrus trees such as orange, lemon and grapefruit thrive on the coastal plain. Figs, pomegranates and olives also grow in the cooler hill areas.[8]

The subtropical climate near the Sea of Galilee and in the Jordan River Valley is suitable for mangoes, kiwis and bananas, while the temperate climate of the mountains of the Galilee and the Golan is suitable for grapes, apples and cherries.[20]

Israeli eating customs also conform to the wider Mediterranean region, with lunch, rather than dinner, being the focal meal of a regular workday.

"Kibbutz foods" have been adopted by many Israelis for their light evening meals as well as breakfasts, and may consist of various types of cheeses, both soft and hard, yogurt, labne and sour cream, vegetables and salads, olives, hard-boiled eggs or omelets, pickled and smoked herring, a variety of breads, and fresh orange juice and coffee.[7]

In addition, Jewish holidays influence the cuisine, with the preparation of traditional foods at holiday times, such as various types of challah (braided bread) for Shabbat and festivals, jelly doughnuts (sufganiyot) for Hanukah, the hamantaschen pastry (oznei haman) for Purim, charoset, a type of fruit paste, for Passover, and dairy foods for Shavuot.

The Shabbat dinner, eaten on Friday, and to a lesser extent the Shabbat lunch, is a significant meal in Israeli homes, together with holiday meals.[19]

Although many, if not most, Jews in Israel do not keep kosher, the tradition of kashrut strongly influences the availability of certain foods and their preparation in homes, public institutions and many restaurants, including the separation of milk and meat and avoiding the use of non-kosher foods, especially pork and shellfish.

During Passover, bread and other leavened foods are prohibited to observant Jews and matza and leaven-free foods are substituted.[21]

Foods

Israel does not have a universally recognized national dish; in previous years this was considered to be falafel, deep-fried balls of seasoned, ground chickpeas.[22][23] Street vendors throughout Israel used to sell falafel, it was a favorite "street food" for decades and is still popular as a mezze dish or as a top-up for hummus-in-pita, though less nowadays as a sole filling in pita due to the frying in deep oil and higher health awareness.[12]

The Israeli breakfast has always been largely healthy, by today's standards, and one book called the Israeli breakfast "the Jewish state's contribution to world cuisine".[24]

Salads and appetizers

Vegetable salads are eaten with most meals, including the traditional Israeli breakfast, which will usually include eggs, bread, and dairy products such as yogurt or cottage cheese. For lunch and dinner, salad may be served as a side dish. A light meal of salad (salat), hummus and French fries (chips) served in a pita is referred to as hummuschipsalat.[25]

Israeli salad is typically made with finely chopped tomatoes and cucumbers dressed in olive oil, lemon juice, salt and pepper. Variations include the addition of diced red or green bell peppers, grated carrot, finely shredded cabbage or lettuce, sliced radish, fennel, spring onions and chives, chopped parsley, or other herbs and spices such as mint, za'atar and sumac.[25]

Although popularized by the kibbutzim, versions of this mixed salad were brought to Israel from various places. For example, Jews from India prepare it with finely chopped ginger and green chili peppers, North African Jews may add preserved lemon peel and cayenne pepper, and Bukharan Jews chop the vegetables extremely finely and use vinegar, without oil, in the dressing.[26]

Tabbouleh is a Levantine vegan dish (sometimes considered a salad) traditionally made of tomatoes, finely chopped parsley, mint, bulgur and onion, and seasoned with olive oil, lemon juice, and salt. Some Israeli variations of the salad use pomegranate seeds instead of tomatoes.

Sabich salad is a variation of the well known Israeli dish sabich, the ingredients of the salad are eggplant, boiled eggs/hard-boiled eggs, tahini, Israeli salad, potato, parsley and amba.

Kubba is a dish made of rice/semolina/burghul (cracked wheat), minced onions and finely ground lean beef, lamb or chicken. The best-known variety is a torpedo-shaped fried croquette stuffed with minced beef, chicken or lamb. It was brought to Israel by Jews of Iraqi, Kurdish and Syrian origin.

Sambusak is a semi-circular pocket of dough filled with mashed chickpeas, fried onions and spices. There is another variety filled with meat, fried onions, parsley, spices and pine nuts, which is sometimes mixed with mashed chickpeas and breakfast version with feta or tzfat cheese and za'atar. It can be fried or otherwise cooked.

Roasted vegetables includes bell peppers, chili peppers, tomatoes, onions, eggplants and also sometimes potatoes and zucchini. Usually served with grilled meat.

Khamutzim are pickled vegetables made by soaking in water and salt (and sometimes olive oil) in a pot and withdrawing them from air. Ingredients can include cucumber, cabbage, eggplant, carrot, turnip, radish, onion, caper, lemon, olives, cauliflower, tomatoes, chili pepper, bell pepper, garlic and beans.

A large variety of eggplant salads and dips are made with roasted eggplants.[27] Baba ghanoush, called salat ḥatzilim in Israel, is made with tahina and other seasonings such as garlic, lemon juice, onions, herbs and spices. Food writer and historian Gil Marks writes in his book that: "Israelis learned to make baba ghanouj from the Arabs".[28] The eggplant is sometimes grilled over an open flame so that the pulp has a smoky taste. A particularly Israeli variation of the salad is made with mayonnaise called salat ḥatzilim b'mayonnaise.[29]

Eggplant salads are also made with yogurt, or with feta cheese, chopped onion and tomato, or in the style of Romanian Jews, with roasted red pepper.[30]

Tahina is often used as a dressing for falafel,[31] serves as a cooking sauce for meat and fish, and forms the basis of sweets such as halva.[32]

Hummus is a cornerstone of Israeli cuisine, and consumption in Israel has been compared by food critic Elena Ferretti to "peanut butter in America, Nutella in Europe or Vegemite in Australia".[33] Hummus in pita is a common lunch for schoolchildren, and is a popular addition to many meals.

Supermarkets offer a variety of commercially prepared hummus, and some Israelis will go out of their way for fresh hummus prepared at a hummusia, an establishment devoted exclusively to selling hummus.[34]

Salat avocado is an Israeli-style avocado salad, with lemon juice and chopped scallions (spring onions), was introduced by farmers who planted avocado trees on the coastal plain in the 1920s. Avocados have since become a winter delicacy and are cut into salads as well as being spread on bread.[35]

A meze of fresh and cooked vegetable salads, pickled cucumbers and other vegetables, hummus, ful, tahini and amba dips, labneh cheese with olive oil, and ikra is served at festive meals and in restaurants.

Salads include Turkish salad (a piquant salad of finely chopped onions, tomatoes, herbs and spices), tabbouleh, carrot salad, marinated roasted red and green peppers, deep fried cauliflower florets, matbucha, torshi (pickled vegetables) and various eggplant salads.[36][37]

Modern Israeli interpretations of the meze blend traditional and modern, pairing ordinary appetizers with unique combinations such as fennel and pistachio salad, beetroot and pomegranate salad, and celery and kashkaval cheese salad.[38]

Stuffed vegetables, called memula’im, were originally designed to extend cheap ingredients into a meal. They are prepared by cooks in Israel from all ethnic backgrounds and are made with many varying flavors, such as spicy or sweet-and-sour, with ingredients such as bell peppers, chili peppers, figs, onion, artichoke bottoms, Swiss chard, beet, dried fruits, tomato, vine leaves, potatoes, mallow, eggplants and zucchini squash, and stuffing such as meat and rice in Balkan style, bulgur in Middle-Eastern fashion, or with ptitim, a type of Israeli pasta.[39]

The Ottoman Turks introduced stuffed vine leaves in the 16th century and vine leaves are commonly stuffed with a combination of meat and rice, although other fillings, such as lentils, have evolved among the various communities.[40]

Artichoke bottoms stuffed with meat are famous as one of the grand dishes of the Sephardi Jerusalem cuisine of the Old Yishuv.[41] Stuffed dates and dried fruits are served with rice and bulgur dishes. Stuffed half-zucchini has a Ladino name, medias.

Soups and dumplings

A variety of soups are enjoyed, particularly in the winter. Chicken soup has been a mainstay of Jewish cuisine since medieval times and is popular in Israel.[42]

Classic chicken soup is prepared as a simple broth with a few vegetables, such as onion, carrot and celery, and herbs such as dill and parsley.

More elaborate versions are prepared by Sephardim with orzo or rice, or the addition of lemon juice or herbs such as mint or coriander, while Ashkenazim may add noodles.[43] An Israeli adaption of the traditional Ashkenazi soup pasta known as mandlen, called shkedei marak ("soup almonds") in Israel, are commonly served with chicken soup.

Particularly on holidays, dumplings are served with the soup, such as the kneidlach (matzah balls) of the Ashkenazim or the gondi (chickpea dumplings) of Iranian Jews, or kubba, a family of dumplings brought to Israel by Middle Eastern Jews. Especially popular are kubba prepared from bulgur and stuffed with ground lamb and pine nuts, and the soft semolina or rice kubba cooked in soup,[43] which Jews of Kurdish or Iraqi heritage habitually enjoy as a Friday lunchtime meal.[44]

Lentil soup is prepared in many ways, with additions such as cilantro or meat.[45] Other soups include the harira of the Moroccan Jews, a spicy soup of lamb (or chicken), chickpeas, lentils and rice, and a Yemenite bone-marrow soup known as ftut, served on special occasions such as weddings, seasoned with the traditional hawaij spice mix.[46][47]

White bean soup in tomato sauce is common in Jerusalem because Sephardic Jews settled in the city after being expelled from Andalusia.

Grains and pasta

Rice is prepared in numerous ways in Israel, from simple steamed white rice to festive casseroles. It is also cooked with spices and served with almonds and pine nuts.

"Green" rice, prepared with a variety of fresh chopped herbs, is favored by Persian Jews. Another rice dish is prepared with thin noodles that are first fried and then boiled with the rice.

Mujadara is a popular rice and lentil dish, adopted from Arab cuisine. Orez Shu'it is a dish invented in Jerusalem by Sephardic Jews, made of white beans cooked in a tomato stew and served on plain boiled rice; it is eaten widely in the Jerusalem region.

Couscous was brought to Israel by Jews from North Africa. It is still prepared in some restaurants or by traditional cooks by passing semolina through a sieve several times and then cooking it over an aromatic broth in a special steamer pot called a couscoussière. Generally, "instant" couscous is used for home cooking.

Couscous is used in salads, main courses and even some desserts. As a main course, chicken or lamb, or vegetables cooked in a soup flavored with saffron or turmeric are served on steamed couscous.[48][49]

Ptitim is an Israeli pasta which now comes in many shapes, including pearls, loops, stars and hearts, but was originally shaped like grains of rice. It originated in the early days of the State of Israel as a wheat-based substitute for rice, when rice, a staple of the Mizrahi Jews, was scarce.

Israel's first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, is reputed to have asked the Osem company to devise this substitute, and so it was nicknamed "Ben-Gurion rice".

Ptitim can be boiled like pasta, prepared pilaf-style by sautéing and then boiling in water or stock, or baked in a casserole. Like other pasta, it can be flavored in many ways with spices, herbs and sauces. Once considered primarily a food for children, ptitim is now prepared in restaurants both in Israel and internationally.[50]

Bulgur is a kind of dried cracked wheat, served sometimes instead of rice.

Fish

Fresh fish is readily available, caught off Israel's coastal areas of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, or in the Sea of Galilee, or raised in ponds in the wake of advances in fish farming in Israel.

Fresh fish is served whole, in the Mediterranean style, grilled, or fried, dressed only with freshly squeezed lemon juice. Trout (forel), gilthead seabream (denisse), St. Peter's fish (musht) and other fresh fish are prepared this way.[51]

Fish are also eaten baked, with or without vegetables, or fried whole or in slices, or grilled over coals, and served with different sauces.[52]

Fish are also braised, as in a dish called hraime, in which fish such as grouper (better known in Israel by its Arabic name lokus) or halibut is prepared in a sauce with hot pepper and other spices for Rosh Hashanah, Passover and Shabbat by North-African Jews.

Everyday versions are prepared with cheaper kinds of fish and are served in market eateries, public kitchens and at home for weekday meals.[51][52]

Fish, traditionally carp, but now other firm whitefish too, are minced and shaped into loaves or balls and cooked in fish broth, such as the gefilte fish of the Ashkenazi Jews, who also brought pickled herring from Eastern Europe.

Herring is often served at the kiddush that follows synagogue services on Shabbat, especially in Ashkenazi communities. In the Russian immigrant community it may be served as a light meal with boiled potatoes, sour cream, dark breads and schnapps or vodka.[52][53]

Fish kufta is usually fried with spices, herbs and onions (sometimes also pine nuts) and served with tahini or yogurt sauce. Boiled fish kufta is cooked in a tomato, tahini or yogurt sauce.

Tilapia baked with tahini sauce and topped with olive oil, coriander, mint, basil and pine nuts (and sometimes also with fried onions) is a specialty of Tiberias.

Poultry and meat

Chicken is the most widely eaten meat in Israel, followed by turkey.[54] Chicken is prepared in a multitude of ways, from simple oven-roasted chicken to elaborate casseroles with rich sauces such as date syrup, tomato sauce, etc.

Examples include chicken casserole with couscous, inspired by Moroccan Jewish cooking, chicken with olives, a Mediterranean classic, and chicken albondigas (meat balls) in tomato sauce, from Jerusalem Sephardi cuisine.[54]

Albondigas are prepared from ground meat.[55] Similar to them is the more popular kufta which is made of minced meat, herbs and spices and cooked with tomato sauce, date syrup, pomegranate syrup or tamarind syrup with vegetables or beans.

Grilled and barbecued meat are common in Israeli cuisine. The country has many small eateries specializing in beef and lamb kebab, shish taouk, merguez and shashlik. Outdoor barbecuing, known as mangal or al ha-esh (on the fire) is a beloved Israeli pastime.

In modern times, Israel Independence Day is frequently celebrated with a picnic or barbecue in parks and forests around the country.[56]

Skewered goose liver is a dish from southern Tel Aviv. It is grilled with salt and black pepper and sometimes with spices like cumin or Baharat spice mix.

Chicken or lamb baked in the oven is very common with potatoes, and sometimes fried onions as well.

Turkey schnitzel is an Israeli adaptation of veal schnitzel, and is an example of the transformations common in Israeli cooking.[57]

The schnitzel was brought to Israel by Jews from Central Europe, but before and during the early years of the State of Israel veal was unobtainable and chicken or turkey was an inexpensive and tasty substitute. Furthermore, a Wiener schnitzel is cooked in both butter and oil, but in Israel only oil is used, because of kashrut.

Today, most cooks buy schnitzel already breaded and serve it with hummus, tahina, and other salads for a quick main meal. Other immigrant groups have added variations from their own backgrounds—Yemenite Jews, for example, flavor it with hawaij.[12] In addition, vegetarian versions have become popular and the Israeli food company, Tiv′ol, was the first to produce a vegetarian schnitzel from a soya meat-substitute.

Various types of sausage are part of Sephardi and Mizrahi cuisine in Israel. Jews from Tunisia make a sausage, called osban, with a filling of ground meat or liver, rice, chopped spinach, and a blend of herbs and spices. Jews from Syria make smaller sausages, called gheh, with a different spice blend while Jews from Iraq make the sausages, called mumbar, with chopped meat and liver, rice, and their traditional mix of spices.[58]

Moussaka is an oven-baked layer dish ground meat and eggplant casserole that, unlike its Levantine rivals, is served hot.

Meat stews (chicken, lamb and beef) are cooked with spices, pine nuts, herbs like parsley, mint and oregano, onion, tomato sauce or tahini or juices such as pomegranate molasses, pomegranate juice, pomegranate wine, grape wine, arak, date molasses and tamarind. Peas, chickpeas, white beans, cowpeas or green beans are sometimes also added.

Stuffed chicken in Israel is usually stuffed with rice, meat (lamb or beef), parsley, dried fruits like dates, apricots or raisins, spices like cinnamon, nutmeg or allspice; sometimes herbs like thyme and oregano (not the dried ones) are added on the top of the chicken to give it a flavor and then it is baked in the oven.

Dairy products

Many fresh, high quality dairy products are available, such as cottage cheese, white cheeses, yogurts including leben and eshel, yellow cheeses, and salt-brined cheeses typical of the Mediterranean region.[59]

Dairy farming has been a major sector of Israeli agriculture since the founding of the state, and the yield of local milk cows is amongst the highest in the world. Initially, the moshavim (farming cooperatives) and kibbutzim produced mainly soft white cheese as it was inexpensive and nutritious. It became an important staple in the years of austerity and gained a popularity that it enjoys until today.[59]

Soft white cheese, gvina levana, is often referred to by its fat content, such as 5% or 9%. It is eaten plain, or mixed with fruit or vegetables, spread on bread or crackers and used in a variety of pies and pastries.[59]

Labneh is a yogurt-based white cheese common throughout the Balkans and the Middle East. It is sold plain, with za'atar, or in olive oil. It is often eaten for breakfast with other cheeses and bread.[60] In the north of the country, labneh balls preserved in olive oil are more common than in the central and the southern parts.

Adding spices like za'atar, dried oregano or sumac and herbs like thyme, mint or scallions is common when preserving the labneh balls. It is especially common to eat them during breakfast because meat is usually not eaten in the morning.

Tzfat cheese, a white cheese in brine, similar to feta, was first produced by the Meiri dairy in Safed in 1837 and is still produced there by descendants of the original cheese makers. The Meiri dairy also became famous for its production of the Balkan-style brinza cheese, which became known as Bulgarian cheese due to its popularity in the early 1950s among Jewish immigrants from Bulgaria.

Other dairies now also produce many varieties of these cheeses.[59] Bulgarian yogurt, introduced to Israel by Bulgarian Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, is used to make a traditional yogurt and cucumber soup.[61]

In the early 1980s, small privately owned dairies began to produce handmade cheeses from goat and sheep's milk as well as cow's milk, resembling traditional cheeses like those made in rural France, Spain and Italy. Many are made with organic milk. These are now also produced by kibbutzim and the national Tnuva dairy.[59]

Egg dishes

Shakshuka, a North-African dish of eggs poached in a spicy tomato sauce, is a national favorite, especially in the winter. It is traditionally served up in a cast-iron pan with bread to mop up the sauce.[62] Some variations of the dish are cooked with liberal use of ingredients such as eggplant, chili peppers, hot paprika, spinach, feta cheese or safed cheese.

Omelettes are seasoned with onions, herbs such as dill seeds (shamir), spinach, parsley, mint, coriander and mallow with spices such as turmeric, cumin, sumac, cinnamon and cloves and with cheese such as safed and feta.

Haminados are eggs that are baked after being boiled, served alongside stew or meals; in hamin they are used in the morning for breakfast, also sometimes replacing the usual egg in sabich. They are also eaten as a breakfast alongside jachnun, grated tomatoes and skhug.

Fruit

Israel is one of the world's leading fresh citrus producers and exporters,[63] and more than forty types of fruit are grown in Israel, including citrus fruits such as oranges, grapefruit, tangerines and the pomelit, a hybrid of a grapefruit and a pomelo, developed in Israel.[64] Fruits grown in Israel include avocados, bananas, apples, cherries, plums, lychees, nectarines, grapes, dates, strawberries, prickly pear (tzabbar), persimmon, loquat (shesek) and pomegranates, and are eaten on a regular basis. Israelis consume an average of nearly 160 kg (350 lb) of fruit per person a year.[65]

Many unique varieties of mango are native to the country, most having been developed during the second half of the 20th century. New and improved mango varieties are still introduced to markets every few years.

Arguably the most popular variety is the Maya type, which is small to medium in size, fragrant, colourful (featuring 3-4 colours) and usually fiberless. The Israeli mango season begins in May, and the last of the fruit ripen as October draws near. Different varieties are present on markets at different months, with the Maya type seen between July and September. Mangos are frequently used in fusion dishes and for making sorbet.

A lot of Israelis keep fruit trees in their yards, citrus (especially orange and lemon) being the most common. Mangos are also now popular as household trees. Mulberry trees are frequently seen in public gardens, and their fruit is popularly served alongside various desserts and as a juice.

Fruit is served as a snack or dessert alongside other items or by themselves. Fresh-squeezed fruit juices are prepared at street kiosks, and sold bottled in supermarkets.[65] Various fruits are added to chicken or meat dishes and fresh fruit salad and compote are often served at the end of the meal.[66]

Baked dishes, cookies, pastries, rugelach

There is a strong tradition of home baking in Israel arising from the years when there were very few bakeries to meet demand. Many professional bakers came to Israel from Central Europe and founded local pastry shops and bakeries, often called konditoria, thus shaping local tastes and preferences.

There is now a local style with a wide selection of cakes and pastries that includes influences from other cuisines and combines traditional European ingredients with Mediterranean and Middle-Eastern ingredients, such as halva, phyllo dough, dates, and rose water.[67]

Examples include citrus-flavored semolina cakes, moistened with syrup and called basbousa, tishpishti or revani in Sephardic bakeries. The Ashkenazi babka has been adapted to include halva or chocolate spread, in addition to the old-fashioned cinnamon. There are also many varieties of apple cake. Cookies made with crushed dates (ma'amoul) are served with coffee or tea, as throughout the Middle East.[67]

Jerusalem kugel (kugel yerushalmi) is an Israeli version of the traditional noodle pudding, kugel, made with caramelized sugar and spiced with black pepper.[68] It was originally a specialty of the Ashkenazi Jews of the Old Yishuv.[11] It is typically baked in a very low oven overnight and eaten after synagogue services on Shabbat morning.[69]

Bourekas are savory pastries brought to Israel by Jews from Turkey, the Balkans and Salonika. They are made of a flaky dough in a variety of shapes, frequently topped with sesame seeds, and are filled with meat, chickpeas, cheese, spinach, potatoes or mushrooms. Bourekas are sold at kiosks, supermarkets and cafes, and are served at functions and celebrations, as well as being prepared by home cooks.[70] They are often served as a light meal with hardboiled eggs and chopped vegetable salad.[71]

Ashkenazi Jews from Vienna and Budapest brought sophisticated pastry making traditions to Israel. Sacher torte and Linzer torte are sold at professional bakeries, but cheesecake and strudel are also baked at home.[72]

Jelly donuts (sufganiyot), traditionally filled with red jelly (jam), but also custard or dulce de leche, are eaten as Hanukkah treats.[73]

Tahini cookies are an Israeli origin cookies made of tahini, flour, butter and sugar and usually topped with pine nuts.

Rugelach is very popular in Israel, commonly found in most cafes and bakeries. It is also a popular treat among American Jews.

Breads and sandwiches

In the Jewish communities of the Old Yishuv, bread was baked at home. Small commercial bakeries were set up in the mid-19th century. One of the earliest, Berman's Bakery, was established in 1875, and evolved from a cottage industry making home-baked bread and cakes for Christian pilgrims.[74]

Expert bakers who arrived among the immigrants from Eastern and Central Europe in the 1920s–30s introduced handmade sourdough breads.

From the 1950s, mass-produced bread replaced these loaves and standard, government subsidized loaves known as leḥem aḥid became mostly available until the 1980s, when specialized bakeries again began producing rich sourdough breads in the European tradition, and breads in a Mediterranean style with accents such as olives, cheese, herbs or sun-dried tomatoes. A large variety of breads is now available from bakeries and cafes.[74]

Challah bread is widely purchased or prepared for Shabbat. Challah is typically an egg-enriched bread, often braided in the Ashkenazi tradition, or round for Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year.[75]

Shabbat and festival breads of the Yemenite Jews have become popular in Israel and can be bought frozen in supermarkets.

Jachnun is very thinly rolled dough, brushed with oil or fat and baked overnight at a very low heat, traditionally served with a crushed or grated tomato dip, hard-boiled eggs and skhug. Malawach is a thin circle of dough toasted in a frying pan. Kubaneh is a yeast dough baked overnight and traditionally served on Shabbat morning. Lahoh is a spongy, pancake-like bread made of fermented flour and water, and fried in a pan. Jews from Ethiopia make a similar bread called injera from millet flour.[76]

Pita bread is a double-layered flat or pocket bread traditional in many Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cuisines. It is baked plain, or with a topping of sesame or nigella seeds or za'atar.

Pita is used in multiple ways, such as stuffed with falafel, salads or various meats as a snack or fast food meal; packed with schnitzel, salad and French fries for lunch; filled with chocolate spread as a snack for schoolchildren; or broken into pieces for scooping up hummus, eggplant and other dips.

A lafa is larger, soft flatbread that is rolled up with a falafel or shawarma filling.[77] Various ethnic groups continue to bake traditional flat breads. Jews from the former Soviet republic of Georgia make the flatbread, lavash.[74]

Confections, sweets and snack foods

Baklava is a nut-filled phyllo pastry sweetened with syrup served at celebrations in Jewish communities who originated in the Middle East.[78] It is also often served in restaurants as dessert, along with small cups of Turkish coffee.

Kadaif is a pastry made from long thin noodle threads filled with walnuts or pistachios and sweetened with syrup; it is served alongside baklava.

Halva is a sweet, made from tehina and sugar, and is popular in Israel. It is used to make original desserts like halva parfait.[79]

Ma'amoul are small shortbread pastries filled with dates, pistachios or walnuts (or occasionally almonds, figs, or other fillings).

Ozne Haman is a sweet yeast dough filled with crushed nuts, raisins, dried apricots, dates, halva or strawberry jam then oven baked, a specialty of Purim. The triangular shape may have been influenced by old illustrations of Haman, in which he wore a three-cornered hat

Sunflower seeds, called garinim (literally, seeds), are eaten everywhere, on outings, at stadiums and at home, usually purchased unshelled and are cracked open with the teeth. They can be bought freshly roasted from shops and market stalls that specialize in nuts and seeds as well as packaged in supermarkets, along with the also well-liked pumpkin and watermelon seeds, pistachios, and sugar-coated peanuts.[80]

Bamba is a soft, peanut-flavored snack food that is a favorite of children, and Bissli is a crunchy snack made of deep-fried dry pasta, sold in various flavors, including BBQ, pizza, falafel and onion.

Malabi is a creamy pudding originating from Turkey prepared with milk or almond milk (for a kosher version) and cornstarch.

It is sold as a street food from carts or stalls, in disposable cups with thick sweet syrup and various crunchy toppings such as chopped pistachios or coconut. Its popularity has resulted in supermarkets selling it in plastic packages and restaurants serving richer and more sophisticated versions using various toppings and garnishes such as berries and fruit.[81][82] Sahlab is a similar dessert made from the powdered tubers of orchids and milk.[81]

Watermelon with feta cheese salad is a popular dessert, sometimes mint is added to the salad.

Krembo is a chocolate-coated marshmallow treat sold only in the winter, and is a very popular alternative to ice cream. It comes wrapped in colorful aluminum foil, and consists of a round biscuit base covered with a dollop of marshmallow cream coated in chocolate.[83]

Milky is a popular dairy pudding that comes in chocolate, vanilla and mocha flavors with a layer of whipped cream on top.[84]

Sauces, spices and condiments

Chili-based hot sauces are prominent in Israeli food, and are based on green or red chili peppers. They are served with appetizers, felafel, casseroles and grilled meats, and are blended with hummus and tahina. Although originating primarily from North African and Yemenite immigrants, these hot sauces are now widely consumed.[85]

Skhug is a spicy chili pepper sauce brought to Israel by Yemenite Jews, and has become one of Israel's most popular condiments. It is added to falafel and hummus and is also spread over fish, and to white cheese, eggs, salami or avocado sandwiches for extra heat and spice.[86]

Other hot sauces made from chili peppers and garlic are the Tunisian harissa, and the filfel chuma of the Libyan Jewish community in Israel.[87]

Amba is a pickled mango sauce, introduced by Iraqi Jews, and commonly used a condiment with shawarma, kebabs, meorav yerushalmi and falafel and vegetable salads.[87]

Concentrated juices made of grape, carob, pomegranate and date are common in different regions, they are used at stews, soups or as a topping for desserts such as malabi and rice pudding.

Almond syrup flavored with rose water or orange blossom water is a common flavor for desserts and sometimes added to cocktails such as arak.

Sumac, a dark red spice is made by grinding the dried berries of the sumac bush, which is native to the Middle East, into a coarse powder. T[88]

Drinks

There is a strong coffee-drinking culture in Israel.[89] Coffee is prepared as instant (nes), iced, latte (hafuḥ), Italian-style espresso, or Turkish coffee, which is sometimes flavored with cardamom (hel).[49] Jewish writers, artists, and musicians from Germany and Austria who immigrated to Israel before the Second World War introduced the model of the Viennese coffee house with its traditional décor, relaxed atmosphere, coffee and pastries.[90]

Cafés are found everywhere in urban areas and function as meeting places for socializing and conducting business. Almost all serve baked goods and sandwiches and many also serve light meals. There are both chains and locally owned neighborhood cafés. Most have outdoor seating to take advantage of Israel's Mediterranean climate. Tel Aviv is particularly well known for its café culture.[91]

Tea is also a widely consumed beverage and is served at cafés and drunk at home. Tea is prepared in many ways, from plain brewed Russian and Turkish-style black tea with sugar, to tea with lemon or milk, and, available as a common option in most establishments, Middle Eastern-style with mint (nana).[92] Tea with rose water is also common.

Limonana, a type of lemonade made from freshly-squeezed lemons and mint, was invented in Israel in the early 1990s and has become a summer staple throughout the Middle East.[93][94]

Rimonana is similar to limonana, made of pomegranate juice and mint.

Sahlab is a drinkable pudding once made of the powdered bulb of the orchid plant but today usually made with cornstarch. It is usually sold in markets or by street vendors, especially in the winter. It is topped with cinnamon and chopped pistachios.[95]

Malt beer, known as black beer (בִירָה שְחוֹרָה, bira shḥora), is a non-alcoholic beverage produced in Israel since pre-state times. Goldstar and Maccabi are Israeli beers. Recently, some small boutique breweries began brewing new brands of beer, such as Dancing Camel,[96] Negev,[97] and Can'an.

Arak is a Levantine alcoholic spirit (~40–63% Alc. Vol./~80–126 proof) from the anis drinks family, common in Israel and throughout the Middle East. It is a clear, colorless, unsweetened anise-flavored distilled alcoholic drink (also labeled as an apéritif).

It is often served neat or mixed with ice and water, which creates a reaction turning the liquor a milky-white colour. It is sometimes also mixed with grapefruit juice to create a cocktail known as arak eshkoliyyot.

Other spirits, brandies, liquors can be found across the country in many villages and towns.

Wine

The vast majority of Israelis drink wine in moderation, and almost always at meals or social occasions. Israelis drink about 6.5 liters of wine per person per year, which is low compared to other wine-drinking Mediterranean countries, but the per capita amount has been increasing since the 1980s as Israeli production of high-quality wine grows to meet demand, especially of semi-dry and dry wines. In addition to Israeli wines, an increasing number of wines are imported from France, Italy, Australia, the United States, Chile and Argentina.[98]

Most of the wine produced and consumed from the 1880s was sweet, kosher wine when the Carmel Winery was established,[99] until the 1980s, when more dry or semi-dry wines began to be produced and consumed after the introduction of the Golan Heights Winery’s first vintage.[100] The winery was the first to focus on planting and making wines from Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot noir, white Riesling and Gewürztraminer. These wines are kosher and have won silver and gold medals in international competitions.[101]

Israeli wine is now produced by hundreds of wineries, ranging in size from small boutique wineries in the villages to large companies producing over 10 million bottles per year, which are also exported worldwide.

Wine made of fruits other than grapes such as fig, cherry, pomegranate, carob and date are also common in the country.

Non-kosher foods

Foods variously prohibited in Jewish dietary laws (kashrut) and in Muslim dietary laws (halal) may also be included in pluralistic Israel's diverse cuisine. Although partly legally restricted,[102][103] pork and shellfish are available at many non-kosher restaurants (only around a third of Israeli restaurants have a kosher license[104]) and some stores all over the country which are widely spread, including by the Maadaney Mizra, Tiv Ta'am and Maadanei Mania[105] supermarket chains.[106]

A modern Hebrew euphemism for pork is "white meat".[106] Despite Jewish and Muslim religious restrictions on the consumption of pork, pigmeat consumption per capita was 2.7 kg (6.0 lb) in 2009.[107]

A 2008 survey reported that about half of Israeli Jews do not always observe kashrut.[108] Israel's anomalous equanimity toward its religious dietary restrictions may be reflected by the fact that some of the Hebrew cookbooks of Yisrael Aharoni are published in two versions: kosher and non-kosher editions.

Eating out

Street foods

In Israel, as in many other Middle Eastern countries, "street food" is a kind of fast food that is sometimes literally eaten while standing in the street, while in some cases there are places to sit down. The following are some foods that are usually eaten in this way:

Falafel are fried balls or patties of spiced, mashed chickpeas or fava beans and are a common Middle-Eastern street food that have become identified with Israeli cuisine. Falafel is most often served in a pita, with pickles, tahina, hummus, cut vegetable salad and often, harif, a hot sauce, the type used depending on the origin of the falafel maker.[12]

Variations include green falafel, which include parsley and coriander, red falafel made with filfel chuma, yellow falafel made with turmeric, and falafel coated with sesame seeds.[109]

Shawarma, (from çevirme, meaning "rotating" in Turkish) is usually made in Israel with turkey, with lamb fat added. The shawarma meat is sliced and marinated and then roasted on a huge rotating skewer.

The cooked meat is shaved off and stuffed into a pita, with hummus and tahina, or with additional trimmings such as fresh or fried onion rings, French fries, salads and pickles. More upscale restaurant versions are served on an open flat bread, a lafa, with steak strips, flame roasted eggplant and salads.[110]

Shakshouka, originally a workman's breakfast popularized by North-African Jews in Israel, is made simply of fried eggs in spicy tomato sauce, with other vegetable ingredients or sausage optional.

Shakshouka is typically served in the same frying pan in which it is cooked, with thick slices of white bread to mop up the sauce, and a side of salad. Modern variations include a milder version made with spinach and feta without tomato sauce, and hot-chili shakshouka, a version that includes both sweet and hot peppers and coriander.[111] Shakshouka in pita is called shakshouka be-pita.[112]

Jerusalem mixed grill, or me'urav Yerushalmi, consists of mixed grill of chicken giblets and lamb with onion, garlic and spices. It is one of Jerusalem's most popular and profitable street foods.[113] Although the origin of the dish is in Jerusalem, it is today common in all of the cities and towns in Israel.

Jerusalem bagels, unlike the round, boiled and baked bagels popularized by Ashkenazi Jews, are long and oblong-shaped, made from bread dough, covered in za’atar or sesame seeds, and are soft, chewy and sweet. They have become a favorite snack for football match crowds, and are also served in hotels as well as at home.[114]

Malabi is a creamy pudding originating from Turkey prepared with milk or cream and cornstarch. It is sold as a street food from carts or stalls, in disposable cups with thick sweet syrup and various crunchy toppings such as chopped pistachios or coconut. Its popularity has resulted in supermarkets selling it in plastic packages and restaurants serving richer and more sophisticated versions using various toppings and garnishes such as berries and fruit.[81][82] Sahlab is a similar dessert made from the powdered tubers of orchids and milk.[81]

Sabikh is a traditional sandwich that Mizrahi Jews introduced to Israel and is sold at kiosks throughout the country, but especially in Ramat Gan, where it was first introduced. Sabiḥ is a pita filled with fried eggplant, hardboiled egg, salad, tehina and pickles.[115]

Tunisian sandwich is usually made from a baguette with various fillings that may include tuna, egg, pickled lemon, salad, and fried hot green pepper.[115]

Places to eat

There are thousands of restaurants, casual eateries, cafés and bars in Israel, offering a wide array of choices in food and culinary styles.[116][117] Places to eat out that are distinctly Israeli include the following:

Falafel stands or kiosks are common in every neighborhood. Falafel vendors compete to stand apart from their competitors and this leads to the offering of additional special extras like chips, deep-fried eggplant, salads and pickles for the price of a single portion of falafel.[109]

A hummusia is an establishment that offers mainly hummus with a limited selection of extras such as tahina, hardboiled egg, falafel, onion, pickles, lemon and garlic sauce and pita or taboon bread.[118]

Misada Mizrahit (literally "Eastern restaurant") refers to Mizrahi Jewish, Middle-Eastern or Arabic restaurants. These popular and relatively inexpensive establishments often offer a selection of meze salads followed by grilled meat with a side of french fries and a simple dessert such as chocolate mousse for dessert.[119]

Steakiyot are meat grills selling sit down and take-away chicken, turkey or lamb as steak, shishlik, kebab and even Jerusalem mixed grill, all in pita or in taboon bread.[120]

Holiday cuisine

Sabbath

Friday night (eve of Shabbat) dinners are usually family and socially oriented meals. Along with family favorites, and varying to some extent according to ethnic background, traditional dishes are served, such as challah bread, chicken soup, salads, chicken or meat dishes, and cakes or fruits for dessert.

Shabbat lunch is also an important social meal. Since antiquity, Jewish communities all over the world devised meat casseroles that begin cooking before lighting of candles that marks the commencement of Shabbat on Friday night, so as to comply with religious regulations for observing Shabbat.

In modern Israel, this filling meal, in many variations, is still eaten on the Sabbath day, not only in religiously observant households, and is also served in some restaurants during the week.[121]

The basic ingredients are meat and beans or rice simmered overnight on a hotplate or blech, or placed in a slow oven. Ashkenazi cholent usually contains meat, potatoes, barley and beans, and sometimes kishke, and seasonings such as pepper and paprika.

Sephardi hamin contains chicken or meat, rice, beans, garlic, sweet or regular potatoes, seasonings such as turmeric and cinnamon, and whole eggs in the shell known as haminados.[122][123]

Moroccan Jews prepare variations known as dafina or skhina (or s′hina) with meat, onion, marrow bones, potatoes, chickpeas, wheat berries, eggs and spices such as turmeric, cumin, paprika and pepper. Iraqi Jews prepare tebit, using chicken and rice.[121][124]

For desserts or informal gatherings on Shabbat, home bakers still bake a wide variety of cakes on Fridays to be enjoyed on the Sabbath, or purchased from bakeries or stores, cakes such as sponge cake, citrus semolina cake, cinnamon or chocolate babkas, and fruit and nut cakes.[67]

Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, is widely celebrated with festive family meals and symbolic foods. Sweetness is the main theme and the Rosh Hashana dinners typically begin with apples dipped in honey, and end with honey cake.

The challah is usually round, often studded with raisins and drizzled with honey, and other symbolic fruits and vegetables are eaten as an entree, such as pomegranates, carrots, leeks and beets.[125]

Fish dishes, symbolizing abundance, are served; for example, gefilte fish is traditional for Ashkenazim, while Moroccan Jews prepare the spicy fish dish, chraime.

Honey cake (lekach) is often served as dessert, accompanied by tea or coffee.[125] Dishes cooked with pomegranate juice are common during this period.

Hanukkah

The holiday of Hanukkah is marked by the consumption of traditional Hanukkah foods fried in oil in commemoration of the miracle in which a small quantity of oil sufficient for one day lasted eight days.

The two most popular Hannukah foods are potato pancakes, levivot, also known by the Yiddish latkes; and jelly doughnuts, known as sufganiyot in Hebrew, pontshkes (in Yiddish) or bimuelos (in Ladino), as these are deep-fried in oil.[126]

Hannukah pancakes are made from a variety of ingredients, from the traditional potato or cheese, to more modern innovations, among them corn, spinach, zucchini and sweet potato.[125]

Bakeries in Israel have popularized many new types of fillings for sufganiyot besides the standard strawberry jelly filling, and these include chocolate, vanilla or cappuccino cream, and others. In recent years downsized, "mini" sufganiyot have also appeared due to concerns about calories.[127]

Tu BiShvat

Tu BiShvat is a minor Jewish holiday, usually sometime in late January or early February, that marks the "New Year of the Trees". Customs include planting trees and eating dried fruits and nuts, especially figs, dates, raisins, carob, and almonds.[128]

Many Israelis, both religious and secular, celebrate with a kabbalistic-inspired Tu BiShvat seder that includes a feast of fruits and four cups of wine according to the ceremony presented in special haggadot modeled on the Haggadah of Passover for this purpose.[129]

Purim

The festival of Purim celebrates the deliverance of the Jewish people from the plot of Haman to annihilate them in the ancient Persian Achaemenid Empire, as described in the Book of Esther.

It is a day of rejoicing and merriment, on which children, and many adults, wear costumes.[130] It is customary to eat a festive meal, seudat Purim,[131] in the late afternoon, often with wine as the prominent beverage, in keeping with the atmosphere of merry-making.[130]

Many people prepare packages of food that they give to neighbors, friends, family, and colleagues on Purim. These are called mishloach manot ("sending of portions"), and often include wine and baked goods, fruit and nuts, and sweets.[130]

The food most associated with Purim is called oznei haman ("Haman's ears"). These are three-cornered pastries filled most often with poppy seeds, but also other fillings. The triangular shape may have been influenced by old illustrations of Haman, in which he wore a three-cornered hat.[132]

Passover

The week-long holiday of Passover in the spring commemorates the Exodus from Egypt, and in Israel is usually a time for visiting friends and relatives, travelling, and on the first night of Passover, the traditional ritual dinner, known as the Seder.

Foods containing ḥametz—leavening or yeast—may not be eaten during Passover. This means bread, pastries and certain fermented beverages, such as beer, cannot be consumed. Ashkenazim also do not eat legumes, known as kitniyot.

Over the centuries, Jewish cooks have developed dishes using alternative ingredients and this characterizes Passover food in Israel today.[133]

Chicken soup with matzah dumplings (kneidlach) is often a starter for the Seder meal among Israelis of all ethnic backgrounds.[133] Spring vegetables, such as asparagus and artichokes often accompany the meal.[133]

Restaurants in Israel have come up with creative alternatives to ḥametz ingredients to create pasta, hamburger buns, pizza, and other fast foods in kosher-for-Passover versions by using potato starch and other non-standard ingredients.

After Passover, the celebration of Mimouna takes place, a tradition brought to Israel by the Jewish communities of North Africa. In the evening, a feast of fruit, confectionery and pastries is set out for neighbors and visitors to enjoy. Most notably, the first leaven after Passover, a thin crepe called a mofletta, eaten with honey, syrup or jam, is served.[134] The occasion is celebrated the following day by outdoor picnics at which salads and barbecued meat feature prominently.

Shavuot

In the early summer, the Jewish harvest festival of Shavuot is celebrated. Shavuot marks the peak of the new grain harvest and the ripening of the first fruits, and is a time when milk was historically most abundant.

To celebrate this holiday, many types of dairy foods (milchig) are eaten. These include cheeses and yogurts, cheese-based pies and quiches called pashtidot, cheese blintzes, and cheesecake prepared with soft white cheese (gvina levana) or cream cheese.[135]

Allegations of cultural appropriation

The labelling of the foodstuffs originating outside of Israel as "Israeli" has led to the charge of cultural appropriation being raised by some critics.[6][failed verification] A notable example that has been lamented by Palestinians, Lebanese and other Arab populations is falafel,[6] which has been proclaimed as an Israeli national dish despite being of likely Egyptian origin.[136][137] Though never a specifically Jewish dish, it has been long been consumed by Syrian and Egyptian Jews,[138][139] and was adopted into the diet of early Jewish immigrants to the Jewish communities of Ottoman Syria.[6] As it is plant-based, Jewish dietary laws classify it as pareve and thus allow it to be eaten with both meat and dairy meals.[140] Palestinian-Jordanian academic Joseph Massad has characterized the celebration of falafel and other dishes of Arab origin in American and European restaurants as Israeli to be part of a broader trend of "colonial conquest".[141] The Lebanese Industrialists' Association has raised assertions of copyright infringement against Israel concerning falafel.[139][142] [143]

See also

- Cuisine of the Mizrahi Jews

- Cuisine of the Sephardic Jews

- Jewish cuisine

- Ancient Israelite cuisine

- Kosher restaurant

- List of Israeli dishes

- List of restaurants in Israel

- Mediterranean diet

- Mediterranean cuisine

- Middle Eastern cuisine

- Levantine cuisine

- Mesopotamian cuisine

- Assyrian cuisine

- Cypriot cuisine

- Yemeni cuisine

- Egyptian cuisine

- Turkish cuisine

- North African cuisine

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gold, Rozanne A Region's Tastes Commingle in Israel Archived 2011-09-17 at the Wayback Machine (July 20, 1994) in The New York Times Retrieved 2010–02–14

- ^ Michael Ashkenazi (10 November 2020). Food Cultures of Israel: Recipes, Customs, and Issues. ABC-CLIO. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4408-6686-9.

- ^ Sardas-Trotino, Sarit NY Times presents: Israeli cuisine course Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine (February 19, 2010) in Ynet – LifeStyle Retrieved 2010–02–19

- ^ Gur, The Book of New Israeli Food, pg. 11

- ^ Kassis, Reem (18 February 2020). "Here's why Palestinians object to the term 'Israeli food': It erases us from history". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Pilcher, Jeffrey M. (2006). Food in World History. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-415-31146-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Roden, The Book of Jewish Food, pp 202-207

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ansky, The Food of Israel, pp. 6-9

- ^ Zisling, Yael, The Biblical Seven Species Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine in Gems in Israel, Retrieved 2010-02-14

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Gur, pg. 10-16

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marks, The World of Jewish Cooking pg. 203

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Nathan, The Foods of Israel Today

- ^ Superfoods to the rescue Archived 2012-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Jerusalem Post

- ^ Doram Gaunt (2008-05-07). "Don't Leave These Alone". en:haaretz. Archived from the original on 2019-07-20. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ "Independence Day: The feast that moved away from home". Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Our man cooks slowly: Eucalyptus restaurant, Jerusalem Post Archived June 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ansky, pp. 24-26

- ^ Celebrating sixty years of Israeli cuisine (May 2008), Derech HaOchel, No. 82, pp. 36-38 (Hebrew)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Overview: Israeli Food Archived 2014-05-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-09-10

- ^ Homsky, Shaul, author of Fruits Grown in Israel quoted in Nathan, The Foods of Israel Today

- ^ Ansky, pp 15-20

- ^ Nathan, Joan, Falafel: About Israel's signature food Archived October 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine in My Jewish Learning, Retrieved 2010–02–14

- ^ Roden pg. 273

- ^ Dubois, Jill; Rosh, Mair (2004). Cultures of the World: Israel. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. p. 122. ISBN 9780761416692.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur, pg. 20-25

- ^ Roden, pg. 248

- ^ Ansky, pg. 39-40

- ^ Gil Marks (2010). "Baba Ghanouj". Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780544186316.

- ^ Levy, F., pg. 41 Feast from the Mideast, Harper Collins (2003) ISBN 0-06-009361-7

- ^ Gur, pg. 32-36

- ^ Roden, pg. 274

- ^ Gur, pg. 38-42

- ^ Hummus Among Us Archived 2013-05-24 at the Wayback Machine, By Elena Ferretti, Fox News

- ^ Gur, pg. 44-48

- ^ Ansky, pg. 50

- ^ Gur, pp. 50-55

- ^ Ansky pg. 37-38

- ^ Gur, pp. 56-61

- ^ Gur, pp. 149-157

- ^ Ansky, pg. 76

- ^ Roden, pg. 544

- ^ Marks, pg. 54

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur, pp. 194-195

- ^ Ansky, pg. 60

- ^ Ansky, pg. 58

- ^ Gur, pp. 109-115

- ^ Roden, pg. 324

- ^ Gur, pp. 116-119

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ansky, pg. 30

- ^ Gur, pp. 127-128

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur pp. 130-136

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ganor, pg. 68

- ^ Ansky, pg, 98

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur, pp. 142-146

- ^ Ansky, pg. 88

- ^ Gur, pp. 165-175

- ^ Roden, pg. 125

- ^ Roden, pg. 426

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Gur, pp. 218-223

- ^ Ansky pg. 37

- ^ Roden pg. 313

- ^ "Shakshuka: Israel's hottest breakfast dish". Thejc.com. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Ladaniya, Milind, Citrus fruit: biology, technology and evaluation, Elsevier Inc., (2008) pp. 3-4, ISBN 978-0-12-374130-1

- ^ Israeli fruit hybrid lowers cholesterol Archived 2010-12-16 at the Wayback Machine in Israel 21c Innovation News Service Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 2010-02-11

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur, pp. 176-179

- ^ Fruit Salad Archived October 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine in Israeli Foods on Jewish Virtual Library Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 2010–02–14

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gur, pg. 206-215

- ^ Roden, pg. 154

- ^ Ansky, pg. 66

- ^ Gur, pg. 92

- ^ Ansky, pg. 70

- ^ Roden, pg. 170

- ^ Roden, pg. 197

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gur, pp. 158-160

- ^ Gur, pg. 188

- ^ Roden, pg. 549

- ^ Gur, pp. 84–86, 90

- ^ Roden, pg. 581

- ^ Rogov, Daniel, Halvah Parfait Archived October 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine in Jewish Virtual Library Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 2010–02–14

- ^ Ganor pp. 144-145

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gur pg. 98-99

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ansky, pg. 126

- ^ Chestnuts roasting in my gelato Archived 2007-11-09 at the Wayback Machine, (8 November 2007), Haaretz, Retrieved 2010-01-09

- ^ Milky That Everyone Grew Up With Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-10-22

- ^ Ganor, pg. 21-26

- ^ Ansky, pg. 36

- ^ Jump up to: a b pp. 298-299

- ^ "Sumac is the Middle Eastern Spice You Need to Try Right Now | The Nosher". 2 March 2020.

- ^ Bellehsen, Nitsana (January 20, 2010), Israeli coffee culture goes global Archived 2010-02-13 at the Wayback Machine in Israel 21c Innovation News Service Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010–01–20

- ^ Roden, pg. 202

- ^ Gur, pg. 217

- ^ Campbell, Dawn, The Tea Book, Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., (1995) pg. 142, ISBN 1-56554-074-3

- ^ Martinelli, Katherine (11 July 2011). "Limonana: Sparkling Summer". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Siegal, Lilach (29 May 2001). לימונענע וירטואלית [Virtual Limonana]. The Marker (in Hebrew). Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Roden, pg. 629

- ^ "Pub | Dancing Camel | Israel". Dancingcamel.com. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Negev Brewery". Negevbrewery.co.il. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ Rogov, Daniel, Wine Consumption in Israel Archived 2015-11-19 at the Wayback Machine in Jewish Virtual Library Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 2009-12-15

- ^ Levine, Jonathan (December 30, 2000). "Carmel Winery: A Microcosm Of The Middle East". Wine Business Monthly. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ^ Roden pg. 633

- ^ Golan Wines, Awards Archived 2012-11-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-09-10

- ^ Segev, Tom (Jan 27, 2012). "The Makings of History / Pork and the people". HaAretz. Retrieved Apr 6, 2013.

- ^ Barak-Erez, Daphne (2007). Outlawed Pigs: Law, Religion, and Culture in Israel. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299221607. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Petersburg, Ofer (29 January 2007). "Only third of Israel's restaurants kosher". Ynetnews. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Mania Group - Home Page | Mania Group". Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yoskowitz, Jeffrey (April 24, 2008). "On Israel's Only Jewish-Run Pig Farm, It's The Swine That Bring Home the Bacon - Letter From Kibbutz Lahav By April 24, 2008". Forward. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "FAOSTAT". Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ ynet (May 26, 2008). "Poll: 40% of secular Jews keep kosher". Ynetnews. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur, pg. 68

- ^ Gur, pgs 74-76

- ^ Gur, pg. 78-82

- ^ Ronald Ranta; Yonatan Mendel (2014). "Consuming Palestine: Palestine and Palestinians in Israeli food culture". Ethnicities. 14 (3): 412–435. doi:10.1177/1468796813519428. JSTOR 24735540. S2CID 144928551.

- ^ Roden, pg. 128

- ^ Gur, pg. 90

- ^ Jump up to: a b Israeli Street Foods Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-01-24

- ^ Israel’s Restaurants website Archived 2010-01-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010 – 01–24

- ^ Restaurants in Israel: The Israeli Restaurant Guide Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010 – 01–24

- ^ Gur, pg. 44

- ^ Gur, pg. 12

- ^ Gur, pg. 164

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gur, pp. 198-205

- ^ Cooper, Eat and Be Satisfied, pg. 131

- ^ Ansky, pp. 29-30

- ^ Roden, pp. 428-443

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gur, pp. 228-236

- ^ Roden, p. 168.

- ^ Yefet, Orna (4 December 2006) Hanukkah: Doughnuts go healthy Archived 2010-01-14 at the Wayback Machine in ynetnews.com, Retrieved 2009-12-17

- ^ Gur, pg. 245

- ^ Tu BiShvat Customs Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine in Virtual Jerusalem, Retrieved 2009-12-17

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Overview: Purim At Home Archived 2011-05-12 at the Wayback Machine in My Jewish Learning Archived February 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-01-10

- ^ "Seudat Purim - Halachipedia". halachipedia.com. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ Roden, pg. 192

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gur, pp. 250-263

- ^ Roden, pg. 554

- ^ Gur, pp 264-272

- ^ Lee, Alexander (1 January 2019). "Historian's Cookbook - Falafel". History Today. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "The falafel battle: which country cooks it best?". the Guardian. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Petrini, Carlo; Watson, Benjamin (2001). Slow food : collected thoughts on taste, tradition, and the honest pleasures of food. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-931498-01-2. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kantor, Jodi (10 July 2002). "A History of the Mideast in the Humble Chickpea". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Thorne, Matt; Thorne, John (2007). Mouth Wide Open: A Cook and His Appetite. Macmillan. pp. 181–187. ISBN 978-0-86547-628-8. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Joseph Massad (17 November 2021). "Israel-Palestine: How food became a target of colonial conquest". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ MacLeod, Hugh (12 October 2008). "Lebanon turns up the heat as falafels fly in food fight". The Age. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ Nahmias, Roee (10 June 2008). "Lebanon: Israel stole our falafel". Ynet News. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

Bibliography

- Ansky, Sherry, and Sheffer, Nelli, The Food of Israel: Authentic Recipes from the Land of Milk and Honey, Hong Kong, Periplus Editions (2000) ISBN 962-593-268-2

- Cooper, John, Eat and Be Satisfied: A Social History of Jewish Food, New Jersey, Jason Aronson Inc. (1993) ISBN 0-87668-316-2

- Ganor, Avi, and Maiberg, Ron, Taste of Israel: A Mediterranean Feast, BBS Publishing Corporation (1994) ISBN 0-88365-844-5

- Gur, Janna, The Book of New Israeli Food: A Culinary Journey, Schocken (2008) ISBN 0-8052-1224-8

- Marks, Gil, The World of Jewish Cooking: More than 500 Traditional Recipes from Alsace to Yemen, New York, Simon & Schuster (1996) ISBN 0-684-83559-2

- Nathan, Joan, The Foods of Israel Today, Knopf (2001) ISBN 0-679-45107-2

- Roden, Claudia, The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York, New York, Knopf (1997) ISBN 0-394-53258-9

External links

- Asif: Culinary Institute of Israel – non-profit organization and culinary center dedicated to exploring Israel's food culture

- Israel Food Guide – information and recipes

- Overview: Israeli Food – articles and recipes

- Israeli Foods Archived 2016-11-22 at the Wayback Machine – articles and recipes

- Israeli Kitchen – food, wine and bread from the heart of Israel

- The Treasure Box Project – preserving Jewish ethnic cuisines in Israel