Christ of Europe

Christ of Europe, a messianic doctrine based in the New Testament, first became widespread among Poland and other various European nations through the activities of the Reformed Churches in the 16th to the 18th centuries.[1] The doctrine, based in principles of brotherly esteem and regard for one another, was adopted in messianic terms by Polish Romantics, who referred to their homeland as the Christ of Europe or as the Christ of Nations crucified in the course of the foreign partitions of Poland (1772–1795). Their own unsuccessful struggle for independence from outside powers served as an expression of faith in God's plans for Poland's ultimate Rising.[2][3][4]

The concept, which identified Poles collectively with the messianic suffering of the Crucifixion, saw Poland as destined – just like Christ – to return to glory. The idea had roots going back to the days of the Ottoman expansion and the wars against the Muslim Turks. It was reawakened and promoted during Adam Mickiewicz's exile in Paris in the mid-19th century. Mickiewicz (1798-1855) evoked the doctrine of Poland as the "Christ of nations" in his poetic drama Dziady (Forefathers' Eve), considered by George Sand one of the great works of European Romanticism,[5] through a vision of priest called Piotr (Part III, published in 1832). Dziady was written in the aftermath of the 1830 uprising against the Russian rule – an event that greatly impacted the author.[6]

Mickiewicz had helped found a student society (the Philomaths) protesting the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and was exiled (1824–1829) to central Russia as a result.[6] In the poet's vision, the persecution and suffering of the Poles was to bring salvation to other persecuted nations, just as the death of Christ – crucified by his neighbors – brought redemption to mankind.[7] Thus, the phrase "Poland, the Christ of Nations" ("Polska Chrystusem narodów") was born.

Several analysts see the concept as persisting into the modern era.[8][9][10] According to some Holocaust scholars, this view has led to a distorted approach to Polish history following World War II. It has made past Polish wrongdoings against other nationalities sometimes difficult or impossible to acknowledge.[11]

Historical development

[edit]

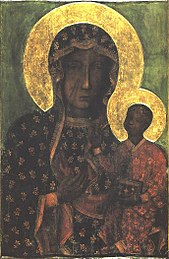

The Polish self-image as a "Christ among nations" or the martyr of Europe can be traced back to its history of Christendom and suffering under invasions.[12] During the periods of foreign occupation, the Catholic Church served as a bastion of Poland's national identity and language, and the major promoter of Polish culture.[13] The invasion by Protestant Sweden in 1656 known as the Deluge helped to strengthen the Polish national tie to Catholicism. The Swedes targeted the national identity and religion of the Poles by destroying its religious symbols. The monastery of Jasna Góra held out against the Swedes and took on the role of a national sanctuary. According to Anthony Smith, even today the Jasna Góra Madonna is part of a mass religious cult tied to nationalism.[14]

Long before Poland was partitioned the privileged classes (szlachta) developed a vision of Roman Catholic Poland (Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at the time) as a nation destined to wage war against Tartars, Turks, Russians, in the defense of Christian Western civilization (Antemurale Christianitatis).[15] The Messianic tradition was stoked by the Warsaw Franciscan Wojciech Dębołęcki who in 1633 made a prophecy of the defeat of the Turks and the world supremacy of the Slavs, themselves in turn led by Poland.[16]

A key element in the Polish view as the guardian of Christianity was the 1683 victory at Vienna against the Turks by John III Sobieski.[a]

Beginning in 1772 Poland suffered a series of partitions by its neighbors Austria, Prussia and Russia, that threatened its national existence. The partitions came to be seen in Poland as a Polish sacrifice for the security of Western civilization.[17]

The failure of the west to support Poland in its 1830 uprising led to the development of a view of Poland as betrayed, suffering, a "Christ of Nations" that was paying for the sins of Europe.[18]

After the failed uprising 10,000 Poles emigrated to France, including many elite. There they came to promote a view of Poland as a heroic victim of Russian tyranny. One of them, Adam Mickiewicz, the foremost 19th-century Polish romanticism poet, wrote the patriotic drama Dziady (directed against the Russians), where he depicts Poland as the Christ of Nations. He also wrote "Verily I say unto you, it is not for you to learn civilization from foreigners, but it is you who are to teach them civilization ... You are among the foreigners like the Apostles among the idolaters".[17]

In "Books of the Polish nation and Polish pilgrimage" Mickiewicz detailed his vision of Poland as a Messias and a Christ of Nations, that would save mankind.[19]

- And Poland said, 'Whosoever will come to me shall be free and equal for I am FREEDOM.' But the Kings, when they heard it, were frightened in their hearts, and they crucified the Polish nation and laid it in its grave, crying out "We have slain and buried Freedom." But they cried out foolishly ...

- For the Polish Nation did not die. Its body lieth in the grave; but its spirit has descended into the abyss, that is, into the private lives of people who suffer slavery in their own country ... For on the Third Day, the Soul shall return to the Body; and the Nation shall arise and free all the peoples of Europe from Slavery.

The last western failure to adequately support Poland, in Poland labeled Western betrayal, is perceived to have come in 1945, at the Yalta conference where the future fate of Europe was being negotiated. The U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Soviet premier Joseph Stalin that "Poland ... has been a source of trouble for over 500 years". The western powers did not attempt to grant Poland the "victor power" status that France was given, despite the Polish military contribution.[20]

During the communist period going to church was a sign of rebellion against the communist regime.[13] During the time of communist martial law in 1981 it became popular to return to the messianic tradition by for example women wearing the Polish eagle on a black cross, jewelry popular after the failed uprising in 1863.[21]

Partly due to communist influenced education (that used is as a symbol of martyrdom of anti-Nazi and anti-fascist resistance), during the Communist era Auschwitz came to take on different meanings for Jews and Poles, with Poles seeing themselves as the "principal martyrs" of the camp.[22]

The Catholic Church, in addition to having provided the main support for the solidarity movement that replaced the communists, also has deep roots of being wedded to the Polish national identity.[23] Polish society is currently struggling with the question of how deeply the Catholic Church shall be allowed to remain attached to Polish national identity.[23]

Contemporary status and criticism

[edit]Several analysts see the concept as a persistent, unifying force in Poland.[8][9][10] A poll taken at the turn of the 20th century indicated that 78% of Poles saw their country as the leading victim of injustice.[24] Its modern applications see Poland as a nation that has "...given the world a Pope and rid the Western world of communism."[8]

This national narrative came under increased scrutiny during the late 20th century, particularly during the controversies surrounding the Auschwitz cross and the Jedwabne massacre. Journalist Tina Rosenberg believes that a "martyr nation" self-conception has dominated the Polish response to revelations about Polish treatment of the Jews in the Jedwabne massacre. She writes that in the resulting debates some have claimed that Jews were trying to slander Poland or have justified past attacks on Jews by alleging Jewish connections to the communists (see Żydokomuna).[25][26][27]

In 1990 Rev. Stanisław Musiał, deputy editor of a leading Catholic newspaper and with a close relationship to then Pope John Paul II called for a Polish reappraisal of history that would take these critiques of nationalist ideology seriously. "We have a mythology of ourselves as martyr nation", he wrote. "We are always good. The others are bad. With this national image, it was absolutely impossible that Polish people could do bad things to others."[28]

Historical proponents

[edit]- Wojciech Dębołęcki

- Zygmunt Krasiński[29]

- Adam Mickiewicz

- Andrzej Towiański

- Stanisław Wyspiański called Poland "the Christ of nations" due to its endurance of suffering[13]

Historical critics

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The European wars of religion did not happen in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The counter-Reformation in Poland "was seen as a triumph of Catholicism, which dominated life and customs. The concept of 'Christian Nation' became synonymous with catholicity. Political and religious threats thus became intertwined. When the Polish nation is threatened, God and God's cause are threatened. Poles view themselves as the only country in northeastern Europe which guards Christianity. A decisive role in consolidating this belief was the victory" at the Battle of Vienna, under the leadership of Sobieski, which Poles regarded "as a unique contribution to Europe" during the Great Turkish War.[4]: 3

References

[edit]- ^ Chris Coleborn, The Relationship of the Reformed Churches of Scotland, England, Western & Eastern Europe from the 1500s to the 1700s, Protestant Reformed Seminary Theological Journal; Volume 36, Number 2, April 2003

- ^ Mesjanizm, historiozofia i symbolika w "Dziadach" cz.III eSzkola.pl 2004–2009: "Widzenie księdza Piotra." Internet Archive.

- ^ King, Sarah Sanderson; Cushman, Donald P. (1992). Political communication: Engineering visions of order in the socialist world. State University of New York Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-7914-1202-2.

- ^ a b Chrostowski, Waldemar (1991). "The suffering, chosenness and mission of the Polish nation". Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. 11 (4). Newberg, OR: George Fox University: 3, 6. ISSN 1069-4781. Archived from the original on 2015-10-03.

- ^ Sand, George (1839-12-01). [Essay on fantastic drama – Goethe, Byron, Mickiewicz]. Revue des deux mondes (in French). Vol. 20. Paris: Revue des deux mondes. ISSN 0035-1962 – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Sorin Antohi, Vladimir Tismăneanu (2000). Between past and future: the revolutions of 1989 and their aftermath. Central European University Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-963-9116-71-9.

- ^ "Polska Chrystusem narodów" at sciaga.pl

- ^ a b c Gerard Delanty; Krishan Kumar (2006). The SAGE handbook of nations and nationalism. SAGE. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4129-0101-7. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ a b Marta Anico; Elsa Peralta (8 January 2009). Heritage and identity: engagement and demission in the contemporary world. Taylor & Francis US. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-45335-6. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ a b Mitchell Young (2007). Nationalism in a global era: the persistence of nations. Taylor & Francis. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-415-41405-0. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ Blobaum, Robert, ed. (2005). Antisemitism and its opponents in modern Poland. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-0-8014-8969-3.

- ^ Dayan, Daniel; Katz, Elihu (1994) [1992]. Media events: The live broadcasting of history. Harvard University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-674-55956-1.

- ^ a b c Sancton, Thomas A. (January 4, 1982). "He dared to hope: Poland's Lech Walesa led a crusade for freedom". Time. p. 5. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023.

- ^ Anthony D. Smith "National Identity" (1993), p. 83. [verification needed]

- ^ Prizel, Ilya (1998-08-13). National identity and foreign policy: Nationalism and leadership in Poland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-521-57697-0. [verification needed]

- ^ Roman Jakobson "Selected writings. 6, Early Slavic paths and crossroads. Comparative Slavic Studies: p. 78. [verification needed]

- ^ a b Prizel 1998, p. 41 [verification needed]

- ^ Prizel 1998, p. 42.

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki "A Concise History of Poland" p.163

- ^ Prizel 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Stefan Auer "Liberal Nationalism in Central Europe" (2004) p.68

- ^ The Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist Poland Sabrina P. Ramet, Catholic Historical Review, July 2007.

- ^ a b Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist Poland, Kumar Krishan, Journal of Political and Military Sociology, Summer 2007

- ^ Marta Anico; Elsa Peralta (8 January 2009). Heritage and identity: engagement and demission in the contemporary world. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-45335-6. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, Tina (April 8, 2001). "editorial-observer-poland-faces-an-ugly-truth-and-doesn-t-blink". The New York Times.

- ^ Lewicka, Maria (2008). "Historical ethnic bias in urban memory: the case of Central European cities". Magazin for Urban Documentation: 51.

- ^ Delanty, Gerard; Kumar, Krishan, eds. (2006). The SAGE handbook of nations and nationalism. London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-0101-7. OCLC 64555613.

- ^ Engelberg, Stephen (November 7, 1990). "A look at Nazi era is urged in Poland". New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ William Safran, The Secular and the Sacred, p. 138. [verification needed]

- ^ Stanislaw Gomulka, Antony Polonsky, Polish Paradoxes, (1991) p. 35. [verification needed]