Characteristics of dyslexia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Dyslexia is a disorder characterized by problems with the visual notation of speech, which in most languages of European origin are problems with alphabet writing systems which have a phonetic construction.[1] Examples of these issues can be problems speaking in full sentences, problems correctly articulating Rs and Ls as well as Ms and Ns, mixing up sounds in multi-syllabic words (ex: aminal for animal, spahgetti for spaghetti, heilcopter for helicopter, hangaberg for hamburger, ageen for magazine, etc.), problems of immature speech such as "wed and gween" instead of "red and green".

The characteristics of dyslexia have been identified mainly from research in languages with alphabetic writing systems, primarily English. However, many of these characteristic may be transferable to other types of writing systems.

The causes of dyslexia are not agreed upon, although the consensus of neuroscientists believe dyslexia is a phonological processing disorder and that dyslexics have reading difficulties because they are unable to see or hear a word, break it down to discrete sounds, and then associate each sound with letters that make up the word. Some researchers believe that a subset of dyslexics have visual deficits in addition to deficits in phoneme processing, but this view is not universally accepted. In any case, there is no evidence that dyslexics literally "see" letters backward or in reverse order within words. Dyslexia is a language disorder, not a vision disorder.

Poor working memory may be another reason why those with dyslexia have difficulties remembering new vocabulary words. Remembering verbal instructions may also be a struggle. Dyslexics who have not been given structured language instruction may grow to depend on learning individual words by memory rather than decoding words by mapping phonemes (speech sounds) to graphemes (letters and letter combinations which represent individual speech sounds).[2]

Listening, speech and language

[edit]Some shared symptoms of the speech or hearing deficits and dyslexia:[3]

- Confusion with before/after, right/left, and so on

- Difficulty learning the alphabet

- Difficulty with word retrieval or naming problems

- Difficulty identifying or generating rhyming words, or counting syllables in words (phonological awareness)

- Difficulty with hearing and manipulating sounds in words (phonemic awareness)

- Difficulty distinguishing different sounds in words (auditory discrimination)

- Difficulty in learning the sounds of letters (In alphabetic writing systems)

- Difficulty associating individual words with their correct meanings

- Difficulty with time keeping and concept of time

- Confusion with combinations of words

- Difficulty in organization skills

The identification of these factors results from the study of patterns across many clinical observations of dyslexic children. In the UK, Thomas Richard Miles was important in such work, and his observations led him to develop the Bangor Dyslexia Diagnostic Test.[4]

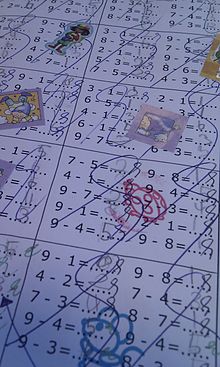

Reading and spelling

[edit]In terms of reading and spelling, it is found that common characteristics include:[5][additional citation(s) needed]

- Spelling errors — Because of difficulty learning letter-sound correspondences, individuals with dyslexia might tend to misspell words, or leave vowels out of words.

- Letter order - People with dyslexia may also reverse the order of two letters, especially when the final, incorrect, word looks similar to the intended word

- Letter addition/subtraction - People with dyslexia may perceive a word with letters added, subtracted, or repeated. This can lead to confusion between two words containing most of the same letters.

- Highly phoneticized spelling - People with dyslexia also commonly spell words inconsistently, but in a highly phonetic form, such as writing "shud" for "should". Dyslexic individuals also typically have difficulty distinguishing among homophones such as "their" and "there".

- Seeing words backwards sometimes - a person sometimes might see the words backwards.

Writing and motor skills

[edit]Because of literacy problems, an individual with dyslexia may have difficulty with handwriting. This can involve slower writing speed than average, poor handwriting characterized by irregularly formed letters, or inability to write straight on a blank paper with no guideline.

Some studies have also reported gross motor difficulties in dyslexia, including motor skills disorder. This difficulty is indicated by clumsiness and poor coordination. The relationship between motor skills and reading difficulties is poorly understood, but could be linked to the role of the cerebellum and inner ear in the development of reading and motor abilities.[6]

Mathematical abilities

[edit]

Dyslexia and dyscalculia are two learning disorders with different cognitive profiles. Dyslexia and dyscalculia have separable cognitive profiles, mainly a phonological deficit in the case of dyslexia and a deficient number module in the case of dyscalculia.[7]

Individuals with dyslexia can be gifted in mathematics while having poor reading skills. They might have difficulty with word processing problems (e.g. descriptive mathematics, engineering or physics problems that rely on written text rather than numbers or formulas).

Adaptive attributes

[edit]A study has found that entrepreneurs are five times more likely to be dyslexic than average citizens.[8][better source needed]

In the United States, researchers estimate the prevalence of dyslexia to range from three to ten percent of school-aged children, though some have put the figure as high as 17 percent.[9][10] Recent studies indicate that dyslexia is particularly prevalent among small business owners, with roughly 20 to 35 percent of US and British entrepreneurs being affected.[11]

Evidence based on randomly selected populations of children indicate that dyslexia affects boys and girls equally; that dyslexia is diagnosed more frequently in boys appears to be the result of sampling bias in school-identified sample populations.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Remien, Kailey; Marwaha, Raman (2022). "Dyslexia". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491600. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Tracy P Alloway Ph.D. | Psychology Today".

- ^ "What are some signs of learning disabilities?". 11 September 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Miles, T.R. (1983). Dyslexia: the Pattern of Difficulties. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-246-11345-6.

- ^ FLETCHER, JACK M. (2009). "Dyslexia: The evolution of a scientific concept". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 15 (4): 501–508. doi:10.1017/S1355617709090900. ISSN 1355-6177. PMC 3079378. PMID 19573267.

- ^ Nicolson, R. and Fawcett, A. (November 1999). "Developmental dyslexia: the role of the cerebellum". Dyslexia. 5 (3): 155–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(199909)5:3<155::AID-DYS143>3.0.CO;2-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Landerl, Karin; Barbara Fussenegger; Kristina Moll; Edith Willburger (2009-07-03). "Dyslexia and dyscalculia: Two learning disorders with different cognitive profiles". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 103 (3): 309–324. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2009.03.006. PMID 19398112.[dead link]

- ^ cass.city.ac.uk Archived 2009-08-20 at the Wayback Machine Entrepreneurs five times more likely to suffer from dyslexia

- ^ Shaywitz, Sally E.; Bennett A. Shaywitz (August 2001). "The Neurobiology of Reading and Dyslexia". Focus on Basics. 5 (A). National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy.

- ^ Learning Disabilities: Multidisciplinary Research Centers, NIH Guide, Volume 23, Number 37, October 21, 1994, Full Text HD-95-005 ("LDRC longitudinal, epidemiological studies show that RD (dyslexia) affect at least 10 million children, or approximately 1 child in 5.")

- ^ Brent Bowers (2007-12-06). "Tracing Business Acumen to Dyslexia". The New York Times. Cites a study by Julie Logan, professor of entrepreneurship at Cass Business School in London, among other literature.

- ^ Shaywitz, Sally E., M.D., and Bennett A. Shaywitz, M.D. (2001) The Neurobiology of Reading and Dyslexia. National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy Focus on Basics, Volume 5, Issue A - August 2001.

Further reading

[edit]- Ellis AW (25 February 2014). Reading, Writing and Dyslexia: A Cognitive Analysis. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-317-71630-3.

- Elliott JG, Grigorenko EL (24 March 2014). The Dyslexia Debate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11986-3.

- Agnew S, Stewart J, Redgrave S (8 October 2014). Dyslexia and Us: A collection of personal stories. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-78333-250-2.

- Norton ES, Beach SD, Gabrieli JD (February 2015). "Neurobiology of dyslexia". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 30: 73–8. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2014.09.007. hdl:1721.1/102416. PMC 4293303. PMID 25290881.