Zvezda (ISS module)

View of the Zvezda module | |

| Module statistics | |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 2000-037A |

| Launch date | 12 July 2000 |

| Launch vehicle | Proton-K |

| Docked | |

| Docking with ISS | |

| Docking port | Zarya aft |

| Docking date | July 26, 2000, 00:45 UTC |

| Time docked | 24 years, 8 days |

| Mass | |

| Length | 13.1 m (43 ft) |

| Width | 29.7 m (97 ft) |

| Diameter | 4.35 m [3] |

| Pressurised volume |

|

| References: [4][5][6] | |

| Configuration | |

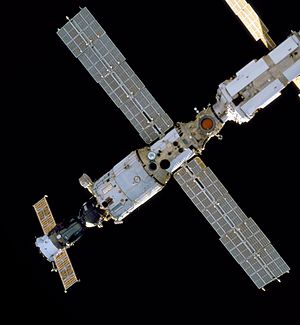

On-orbit configuration of the Zvezda service module | |

Zvezda (Russian: Звезда, meaning "star"), Salyut DOS-8, also known as the Zvezda Service Module, is a module of the International Space Station (ISS). It was the third module launched to the station, and provided all of the station's life support systems, some of which are supplemented in the US Orbital Segment (USOS), as well as living quarters for two crew members. It is the structural and functional center of the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS), which is the Russian part of the ISS. Crew assemble here to deal with emergencies on the station.[7][8][9]

The module was manufactured in the USSR by RKK Energia, with major sub-contracting work by GKNPTs Khrunichev.[10] Zvezda was launched on a Proton launch vehicle on 12 July 2000, and docked with the Zarya module on 26 July 2000 at 00:45 UTC

Origins

[edit]The basic structural frame of Zvezda, known as "DOS-8", was initially built in the mid-1980s to be the core of the Mir-2 space station. This means that Zvezda is similar in layout to the core module (DOS-7) of the Mir space station. It was in fact labeled as Mir-2 for quite some time in the factory. Its design lineage thus extends back to the original Salyut stations. The space frame was completed in February 1985 and major internal equipment was installed by October 1986.

The Mir-2 space station was redesigned after the failure of the Polyus orbital weapons platform core module to reach orbit. Zvezda is around 1⁄4 the size of Polyus, and has no armaments.

Design

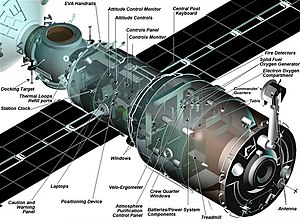

[edit]Zvezda consists of the cylindrical "Work Compartment" where the crews work and live (and which makes up the bulk of the module's volume), the small spherical "Transfer Compartment" located at the front (with three docking ports), and at the aft end the cylindrical "Transfer Chamber" (with one docking port) which is surrounded by the unpressurized "Assembly Compartment" – this gives Zvezda four docking ports in total.[10] The component weighs about 18,051 kg (39,796 lb) and has a length of 13.1 m (43 ft). The solar panels extend 29.7 m (97 ft).

The "Transfer Compartment" attaches to the Zarya module, and has docking ports intended for the Science Power Platform (SPP) and the Universal Docking Module (UDM). As in the early days of Mir, the transfer compartment provides a suitable EVA airlock where spacewalkers in Orlan space suits removed a hatch after closing a few that connected the compartment to the rest of the station. It was used only during Expedition 2, where Yury Usachov and James Voss put a docking cone on the nadir port. The lower port connects to Pirs and the top port connects to Poisk. Eventually, the plan for Pirs was for it to be deorbited on 23 July 2021 and replaced by Nauka (Multipurpose Laboratory Module) docking on 29 July 2021.

The "Assembly Compartment" holds external equipment such as thrusters, thermometers, antennas, and propellant tanks. The large movable "Lira satellite communications antenna" is located on the Zvezda service module near the aft or rear of the International Space Station on this Assembly Compartment.[12] The "Transfer Chamber" is equipped with automatic docking equipment and is used to service Soyuz and Progress spacecraft.

Zvezda can support up to six crew [10] including separate sleeping quarters for two cosmonauts at a time.[10] It also has a NASA-provided Treadmill with Vibration Isolation System, a kitchen equipped with a refrigerator/freezer and a table, a bicycle for exercise, a toilet and other hygiene facilities. The crew's wastewater and condensation water pulled out of the cabin air is recycled. Zvezda has been criticised for being excessively noisy and the crew has been observed wearing earplugs inside it.

Zvezda has 14 windows.[10] There are two 22.5 cm (8.9 in) diameter windows, one in each of the two crew sleep compartments (windows No. 1 and 2), six 22.5 cm (8.9 in) diameter windows (No. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) on the forward Transfer Compartment earth-facing floor, a 40 cm (16 in) diameter window in the main Working Compartment (No. 9), and one 7.5 cm (3.0 in) diameter window in the aft transfer compartment (No. 10). There are a further three 22.5 cm (8.9 in) diameter windows in the forward end of the forward transfer compartment (No. 12, 13 and 14), for observing approaching craft. Window No. 11 is unaccounted for in all available sources.

Zvezda also contains the Elektron system that electrolyzes condensed humidity and waste water to provide hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen is expelled into space and the oxygen (up to 5.13 kg per day is generated) is used for breathing air. The condensed water and the waste water can be used for drinking in an emergency, but ordinarily fresh water from Earth is used. The Elektron system has required significant maintenance work, having failed several times and requiring the crew to use the Solid Fuel Oxygen Generator canisters (also called "oxygen candles", which were the cause of a fire on Mir) when it has been broken for extended amounts of time. It also contains the Vozdukh, a system which removes carbon dioxide from the air based on the use of regenerable absorbers of carbon dioxide gas. Zvezda is also the home of the Lada Greenhouse, which is a test for growing plants in space.[13]

The Service Module has 16 small thrusters as well as two large 3,070-newton (690 lbf) S5.79 thrusters that are 2-axis mounted and can be gimballed 5°. The thrusters are pressure-fed from four tanks with a total capacity of 860 kg.[2] The oxidizer used for the propulsion system is dinitrogen tetroxide and the fuel is UDMH, the supply tanks being pressurised with nitrogen.[14] The two main engines on Zvezda can be used to raise the station's altitude. This was done on 25 April 2007. This was the first time the engines had been fired since Zvezda arrived in 2000.[15]

The Mir space station and Zvezda had the same design problem of launching with all the hardware permanently installed. Russian (and Soviet) space doctrine has always been to fix the hardware onboard instead of simply replacing them like the US Orbital Segment (USOS) does with the 41.3 inch (105 cm) wide International Standard Payload Racks that can easily fit through the 51 inch (130 cm) wide hatch openings through the modules connected via the Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM). This means broken but unfixable hardware onboard the Mir modules and Zvezda end up being stuck there forever and can not be replaced. ESA Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano in 2020 said that the originally installed computers in Zvezda do not work anymore and the central command post's computers are now three Lenovo ThinkPad laptops. The broken computers' monitors, keyboard, and other devices are left there as it is but cannot be removed and replaced. The pre-installed Elektron oxygen generating system also has to be fixed frequently by cosmonauts instead of simply being replaced due to the problem of Zvezda's 78.74 cm (31 inch) wide hatch and the inability to replace the Elektron with another Elektron. Another reason why Elektrons can not be replaced is because the three Elektron units that were launched on Zvezda were the last units ever manufactured. The original manufacturers went out of business and the single engineer who made the tweaks for the Elektrons that were installed on Zvezda died with all his secrets and knowledge not passed to anybody else. [citation needed] In October 2020, the Elektron system malfunctioned yet again and had to be deactivated.[16][17][18][19][20]

Connection to the ISS

[edit]

The rocket used for launch to the ISS carried advertising; it was emblazoned with the logo of Pizza Hut restaurants,[21][22][23] for which they are reported to have paid more than US$1 million.[24] The money helped support Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Center and the Russian advertising agencies that orchestrated the event.[25]

Management and integration of the Service Module into the International Space Station began in 1991. Structural construction was performed by RKK Energia, then handed over to the Khrunichev Design Bureau for final outfitting. Joint reviews between the Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos) and the NASA ISS Program Office monitored construction, solved language and security concerns and ensured flight readiness and crew training. Several years of delay were encountered due to funding constraints between Roscosmos and RKK Energia requiring repeated delays in First Element Launch.

On 26 July 2000, Zvezda became the third component of the ISS when it docked at the aft port of Zarya. (The U.S. Unity module had already been attached to Zarya). Later in July, the computers aboard Zarya handed over ISS commanding functions to computers on Zvezda.[26]

On 11 September 2000, two members of the STS-106 Space Shuttle crew completed final connections between Zvezda and Zarya; during a 6-hour, 14 minute EVA, astronaut Ed Lu and cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko connected nine cables between Zvezda and Zarya, including four power cables, four video and data cables and a fiber-optic telemetry cable.[27] The next day, STS-106 crew members floated into Zvezda for the first time, at 05:20 UTC on 12 September 2000.[28]

Zvezda provided early living quarters, a life support system, a communication system (Zvezda introduced a 10 Mbit/s Ethernet network to the ISS [29]), electrical power distribution, a data processing system, a flight control system, and a propulsion system. These quarters and some, but not all, systems have since been supplemented by additional ISS components.

Launch risks

[edit]Due to Russian financial problems, Zvezda was launched with no backup and no insurance. Due to this risk, NASA had constructed an Interim Control Module (ICM) in case it was delayed significantly or destroyed on launch.[citation needed]

Interior

[edit]-

Zvezda's space toilet

-

Forward view of interior of Zvezda

-

Part of the galley

Crew

[edit]-

Crewmembers celebrating Christmas in Zvezda

-

View of one of the Zvezda crew quarters

-

Cosmonaut in Zvezda, November 2000.

-

Expedition 37 crew in Zvezda

-

Roman Romanenko at a window in Zvezda

Exterior

[edit]-

Zvezda Service Module being manufactured at the Khrunichev factory

-

PMA-2, Unity Node 1, PMA-1, Zarya FGB, Zvezda Service Module, and Progress M1-3.

-

The location of Zvezda in the Russian Orbital Segment

-

Sunrise in orbit overlooking Zvezda and its solar array

-

Russian Orbital Segment windows

-

Zvezda nadir docking port where Pirs and Nauka were docked

-

Zenith docking port on Zvezda where Poisk had docked

Dockings

[edit]

Aft port

- Progress MS-02 63P, 2016

- Progress M-29M 61P, 2015–2016

- Soyuz TMA-16M, 2015 [30]

- Georges Lemaître ATV-5, 2014–2015

- Progress M-21M, 2013–2014

- Soyuz TMA-09M, 2013[31]

- Albert Einstein ATV-4, 2013

- Progress M-17M 49P, 2012–2013

- Edoardo Amaldi ATV-3 2012

- Progress M-11M 43P, 2011

- Johannes Kepler ATV-2 2011

- Progress M-07M 39P, 2010

- Progress M-06M 38P, 2010

- Soyuz TMA-19, 2010[31]

- Soyuz TMA-17, 2010

- Progress M-04M 36P, 2010

- Soyuz TMA-16, 2009–2010

- Progress M-67 34P, 2009

- Jules Verne ATV-1 2008

- Progress M-65 30P, 2008

- Progress M-60 25P, 2007

- Progress M-58 23P, 2006–2007

- Soyuz TMA-9 2006

- Soyuz TMA-7 2006

- Progress M-56 21P, 2006

- Progress M-54 19P, 2005–2006

- Progress M-53 18P, 2005

- Progress M-52 17P, 2005

- Progress M-51 16P, 2004–2005

- Progress M-50 15P, 2004

- Progress M-49 14P, 2004

- Progress M1-11 13P, 2004

- Progress M-48 12P, 2003–2004

- Progress M-47 10P, 2003

- Progress M1-9 9P, 2002–2003

- Progress M-46 8P, 2002

- Progress M1-8 7P, 2002

- Progress M1-7 6P, 2001–2002

- Progress M-45 5P, 2001

- Progress M1-6 4P, 2001

- Progress M-44 3P, 2001

- Progress M1-3 1P, 2000 (1st)

Nadir

Zenith

- Poisk, 2009–present

Forward

- Zarya, 2000–present

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Zvezda Service Module". Khrunichev. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ a b "ISS Elements Service Module Zvezda". Spaceref. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Служебный модуль 'Звезда'" ["Zvezda" service module] (in Russian). Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "The ISS to Date". NASA. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 3 June 2002. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "The ISS to Date". NASA. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 3 June 2002. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "International Space Station Status Report #06-7". NASA. 17 February 2006. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "International Space Station Status Report #06-7". NASA. 17 February 2006. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA – Zvezda Service Module". NASA. 14 October 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA – Zvezda Service Module". NASA. 14 October 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Williams, Sunita (presenter) (3 July 2015). Departing Space Station Commander Provides Tour of Orbital Laboratory (video). NASA. Event occurs at 17.46-18.26. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Williams, Sunita (presenter) (3 July 2015). Departing Space Station Commander Provides Tour of Orbital Laboratory (video). NASA. Event occurs at 17.46-18.26. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Roylance, Frank D. (11 November 2000). "Space station astronauts take shelter from solar radiation". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Stofer, Kathryn (29 October 2013). "Tuesday/Wednesday Solar Punch". NASA. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Stofer, Kathryn (29 October 2013). "Tuesday/Wednesday Solar Punch". NASA. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Service Module | RuSpace". suzymchale.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Photo-iss006e45076". Spaceflight Insider. 22 June 2003. Archived from the original on 22 June 2003.

- ^ "COSMONAUTS PERFORM LONGEST RUSSIAN SPACEWALK TO UPGRADE HIGH-GAIN ANTENNA". 3 February 2018.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Orbiting Agriculture". NASA. 20 October 2005. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Orbiting Agriculture". NASA. 20 October 2005. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Anatoly Zak (18 June 2013). "Zvezda service module (SM)". Russian Space Web. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "International Space Station Status Report: SS07-23". NASA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "International Space Station Status Report: SS07-23". NASA.

- ^ Grand tour of the International Space Station with Drew and Luca | Single take, retrieved 30 July 2021

- ^ "Space station benefits from a wide opening". NBC News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Oxygen supply system deactivated in Russian ISS section due to malfunction". TASS. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly. "A Rare Look at the Russian Side of the Space Station". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Oxygen problems plague space station". NBC News. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Pizza Hut Puts Pie in the Sky with Rocket Logo". Space.com. 30 September 1999. Archived from the original on 14 January 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ^ "Proton Set to Make Pizza Delivery to ISS". SpaceDaily. 8 July 2000. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Geere, Duncan (2 November 2010). "The International Space Station is 10 today!". wired.co.uk. Wired. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "THE MEDIA BUSINESS; Rocket to Carry Pizza Hut Logo". The New York Times. 1 October 1999. Retrieved 21 January 2009.

- ^ "Proton Set to Make Pizza Delivery to ISS". SpaceDaily. AFP. 8 July 2000.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "STS-106". NASA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "STS-106". NASA.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "STS-106 Report # 07". NASA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "STS-106 Report # 07". NASA.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "STS-106 Report # 10". NASA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "STS-106 Report # 10". NASA.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: William Ivancic; Terry Bell; Dan Shell (April 2002). ISS and STS Commercial Off-The-Shelf Router Testing (PDF) (Report). NASA Technical Memo TM-2002-211310. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: William Ivancic; Terry Bell; Dan Shell (April 2002). ISS and STS Commercial Off-The-Shelf Router Testing (PDF) (Report). NASA Technical Memo TM-2002-211310. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Soyuz Relocation". NASA. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Soyuz Relocation". NASA. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ a b Wright, Jerry (13 April 2015). "Soyuz Move Sets Stage for Arrival of New Crew". NASA.

External links

[edit]- Zvezda @ RuSpace Archived 21 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine (includes diagrams)