Dialectical behavior therapy

| Part of a series on |

| Mindfulness |

|---|

|

|

|

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based[1] psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts.[1] Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use.[2] DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.[1]

This approach was developed by Marsha M. Linehan, a psychology researcher at the University of Washington. She defines it as "a synthesis or integration of opposites".[3] DBT was designed to help people increase their emotional and cognitive regulation by learning about the triggers that lead to reactive states and by helping to assess which coping skills to apply in the sequence of events, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to help avoid undesired reactions. Linehan later disclosed to the public her own struggles and belief that she suffers from borderline personality disorder.

DBT grew out of a series of failed attempts to apply the standard cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) protocols of the late 1970s to chronically suicidal clients.[3] Research on its effectiveness in treating other conditions has been fruitful.[4] DBT has been used by practitioners to treat people with depression, drug and alcohol problems,[5] post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),[6] traumatic brain injuries (TBI), binge-eating disorder,[1] and mood disorders.[7][3] Research indicates that DBT might help patients with symptoms and behaviors associated with spectrum mood disorders, including self-injury.[8] Work also suggests its effectiveness with sexual-abuse survivors[9] and chemical dependency.[10]

DBT combines standard cognitive-behavioral techniques for emotion regulation and reality-testing with concepts of distress tolerance, acceptance, and mindful awareness largely derived from contemplative meditative practice. DBT is based upon the biosocial theory of mental illness and is the first therapy that has been experimentally demonstrated to be generally effective in treating borderline personality disorder (BPD).[11][12] The first randomized clinical trial of DBT showed reduced rates of suicidal gestures, psychiatric hospitalizations, and treatment dropouts when compared to usual treatment.[3] A meta-analysis found that DBT reached moderate effects in individuals with BPD.[13] DBT may not be appropriate as a universal intervention, as it was shown to be harmful or have null effects in a study of an adapted DBT skills-training intervention in adolescents in schools, though conclusions of iatrogenic harm are unwarranted as the majority of participants did not significantly engage with the assigned activities with higher engagement predicting more positive outcomes. [14]

Overview

[edit]DBT is sometimes considered a part of the "third wave" of cognitive-behavioral therapy, as DBT adapts CBT to assist patients in dealing with stress.[15][16] DBT focuses on treating disorders that are characterised by impulsivity and emotional dysregulation.[17]

DBT strives to have the patient view the therapist as an accepting ally rather than an adversary in the treatment of psychological issues: many treatments at this time left patients feeling "criticized, misunderstood, and invalidated" due to the way these methods "focused on changing cognitions and behaviors."[1] Accordingly, the therapist aims to accept and validate the client's feelings at any given time, while, nonetheless, informing the client that some feelings and behaviors are maladaptive, and showing them better alternatives.[3] In particular, DBT targets self-harm and suicide attempts by identifying the function of that behavior and obtaining that function safely through DBT coping skills.[18] DBT focuses on the client acquiring new skills and changing their behaviors,[19] with the ultimate goal of achieving a "life worth living".[1]

In DBT's biosocial theory of BPD, clients have a biological predisposition for emotional dysregulation, and their social environment validates maladaptive behavior.[20]

DBT skills training alone is being used to address treatment goals in some clinical settings,[21] and the broader goal of emotion regulation that is seen in DBT has allowed it to be used in new settings, for example, supporting parenting.[22] There has been little study into adapting DBT into an online environment, but a review indicates that attendance is improved online, with comparable improvements for clients to the traditional mode.[23]

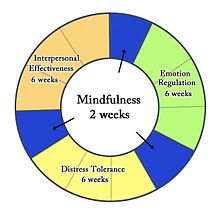

Four modules

[edit]Mindfulness

[edit]

Mindfulness is one of the core ideas behind all elements of DBT. It is considered a foundation for the other skills taught in DBT, because it helps individuals accept and tolerate the powerful emotions they may feel when challenging their habits or exposing themselves to upsetting situations.

The concept of mindfulness and the meditative exercises used to teach it are derived from traditional contemplative religious practice, though the version taught in DBT does not involve any religious or metaphysical concepts. Within DBT it is the capacity to pay attention, nonjudgmentally, to the present moment; about living in the moment, experiencing one's emotions and senses fully, yet with perspective. The practice of mindfulness can also be intended to make people more aware of their environments through their five senses: touch, smell, sight, taste, and sound.[24] Mindfulness relies heavily on the principle of acceptance, sometimes referred to as "radical acceptance". Acceptance skills rely on the patient's ability to view situations with no judgment, and to accept situations and their accompanying emotions. This causes less distress overall, which can result in reduced discomfort and symptomology.

Acceptance and change

[edit]The first few sessions of DBT introduce the dialectic of acceptance and change. The patient must first become comfortable with the idea of therapy; once the patient and therapist have established a trusting relationship, DBT techniques can flourish. An essential part of learning acceptance is to first grasp the idea of radical acceptance: radical acceptance embraces the idea of facing situations, both positive and negative, without judgment. Acceptance also incorporates mindfulness and emotional regulation skills, which depend on the idea of radical acceptance. These skills, specifically, are what set DBT apart from other therapies.

Often, after a patient becomes familiar with the idea of acceptance, they will accompany it with change. DBT has five specific states of change which the therapist will review with the patient: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.[25] Precontemplation is the first stage, in which the patient is completely unaware of their problem. In the second stage, contemplation, the patient realizes the reality of their illness: this is not an action, but a realization. It is not until the third stage, preparation, that the patient is likely to take action, and prepares to move forward. This could be as simple as researching or contacting therapists. Finally, in stage 4, the patient takes action and receives treatment. In the final stage, maintenance, the patient must strengthen their change in order to prevent relapse. After grasping acceptance and change, a patient can fully advance to mindfulness techniques.

There are six mindfulness skills used in DBT to bring the client closer to achieving a "wise mind", the synthesis of the rational mind and emotion mind: three "what" skills (observe, describe, participate) and three "how" skills (nonjudgementally, one-mindfully, effectively).[26]

Distress tolerance

[edit]The concept of distress tolerance arose from methods used in person-centered, psychodynamic, psychoanalytic, gestalt, and/or narrative therapies, along with religious and spiritual practices. Distress tolerance means learning to bear emotional discomfort skillfully, without resorting to maladaptive reactions. Healthier coping behaviors are learned, including intentional self-distraction, self-soothing, and 'radical acceptance.'[26]

Distress tolerance skills are meant to arise naturally as a consequence of mindfulness. They have to do with the ability to accept, in a non-evaluative and nonjudgmental fashion, both oneself and the current situation. It is meant to be a non-judgmental stance, one of neither approval nor resignation. The goal is to become capable of calmly recognizing negative situations and their impact, rather than becoming overwhelmed or hiding from them. This allows individuals to make wise decisions about whether and how to take action, rather than falling into intense, desperate, and often destructive emotional reactions.[27]

Emotion regulation

[edit]Individuals with borderline personality disorder and suicidal individuals are frequently emotionally intense and labile. They can be angry, intensely frustrated, depressed, or anxious. This suggests that these clients might benefit from help in learning to regulate their emotions. Dialectical behavior therapy skills for emotion regulation include:[28]

- Identify and label emotions

- Identify obstacles to changing emotions

- Reduce vulnerability to emotion mind

- Increase positive emotional events

- Increase mindfulness to current emotions

- Take opposite action

- Apply distress tolerance techniques[27]

Emotional regulation skills are based on the theory that intense emotions are a conditioned response to troublesome experiences, the conditioned stimulus, and therefore, are required to alter the patient's conditioned response.[4] These skills can be categorized into four modules: understanding and naming emotions, changing unwanted emotions, reducing vulnerability, and managing extreme conditions:[4]

- Learning how to understand and name emotions: the patient focuses on recognizing their feelings. This segment relates directly to mindfulness, which also exposes a patient to their emotions.

- Changing unwanted emotions: the therapist emphasizes the use of opposite-reactions, fact-checking, and problem solving to regulate emotions. While using opposite-reactions, the patient targets distressing feelings by responding with the opposite emotion.

- Reducing vulnerability: the patient learns to accumulate positive emotions and to plan coping mechanisms in advance, in order to better handle difficult experiences in the future.

- Managing extreme conditions: the patient focuses on incorporating their use of mindfulness skills to their current emotions, to remain stable and alert in a crisis.[4]

Interpersonal effectiveness

[edit]The three interpersonal skills focused on in DBT include self-respect, treating others "with care, interest, validation, and respect", and assertiveness. The dialectic involved in healthy relationships involves balancing the needs of others with the needs of the self, while maintaining one's self-respect.[29]

Tools

[edit]Specially formatted diary cards can be used to track relevant emotions and behaviors. Diary cards are most useful when they are filled out daily.[30] The diary card is used to find the treatment priorities that guide the agenda of each therapy session. Both the client and therapist can use the diary card to see what has improved, gotten worse, or stayed the same.[31]

Chain analysis

[edit]

Chain analysis is a form of functional analysis of behavior but with increased focus on sequential events that form the behavior chain. It has strong roots in behavioral psychology in particular applied behavior analysis concept of chaining.[32] A growing body of research supports the use of behavior chain analysis with multiple populations.[33]

Efficacy

[edit]Borderline personality disorder

[edit]DBT is the therapy that has been studied the most for treatment of borderline personality disorder, and there have been enough studies done to conclude that DBT is helpful in treating borderline personality disorder.[34] Several studies have found there are neurobiological changes in individuals with BPD after DBT treatment.[35]

Depression

[edit]A Duke University pilot study compared treatment of depression by antidepressant medication to treatment by antidepressants and dialectical behavior therapy. A total of 34 chronically depressed individuals over age 60 were treated for 28 weeks. Six months after treatment, statistically significant differences were noted in remission rates between groups, with a greater percentage of patients treated with antidepressants and dialectical behavior therapy in remission.[36][non-primary source needed]

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD)

[edit]Exposure to complex trauma, or the experience of prolonged trauma with little chance of escape, can lead to the development of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) in an individual.[37] The American Psychiatric Association (APA) does not recognize CPTSD as a diagnosis in the DSM-5 (Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the manual used by providers to diagnose, treat and discuss mental illness), though many practitioners argue that CPTSD is separate from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[38] As of 2020, over 40 studies from 15 different countries had "consistently demonstrated the distinction between PTSD and CPTSD" and "replicated the distinct symptoms associated with each disorder" according to a 2021 literature review. [39]

CPTSD is similar to PTSD in that its symptomatology is pervasive and includes cognitive, emotional, and biological domains, among others.[40] CPTSD differs from PTSD in that it is believed to originate in childhood interpersonal trauma, or chronic childhood stress,[40] and that the most common precedents are sexual traumas.[41] Currently, the prevalence rate for CPTSD is an estimated 0.5%, while PTSD's is 1.5%.[41] Numerous definitions for CPTSD exist. Different versions are contributed by the World Health Organization (WHO), The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), and individual clinicians and researchers.

Most definitions revolve around criteria for PTSD with the addition of several other domains. While The APA may not recognize CPTSD, the WHO has recognized this syndrome in its 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). The WHO defines CPTSD as a disorder following a single or multiple events which cause the individual to feel stressed or trapped, characterized by low self-esteem, interpersonal deficits, and deficits in affect regulation.[42] These deficits in affect regulation, among other symptoms are a reason why CPTSD is sometimes compared with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Similarities Between CPTSD and borderline personality disorder

[edit]In addition to affect dysregulation, case studies reveal that patients with CPTSD can also exhibit splitting, mood swings, and fears of abandonment.[43] Like patients with borderline personality disorder, patients with CPTSD were traumatized frequently and/or early in their development and never learned proper coping mechanisms. These individuals may use avoidance, substances, dissociation, and other maladaptive behaviors to cope.[43][better source needed] Thus, treatment for CPTSD involves stabilizing and teaching successful coping behaviors, affect regulation, and creating and maintaining interpersonal connections.[43] In addition to sharing symptom presentations, CPTSD and BPD can share neurophysiological similarities, for example, abnormal volume of the amygdala (emotional memory), hippocampus (memory), anterior cingulate cortex (emotion), and orbital prefrontal cortex (personality).[44] Another shared characteristic between CPTSD and BPD is the possibility for dissociation. Further research is needed to determine the reliability of dissociation as a hallmark of CPTSD, however it is a possible symptom.[44] Because of the two disorders' shared symptomatology and physiological correlates, psychologists began hypothesizing that a treatment which was effective for one disorder may be effective for the other as well.

DBT as a treatment for CPTSD

[edit]DBT's use of acceptance and goal orientation as an approach to behavior change can help to instill empowerment and engage individuals in the therapeutic process. The focus on the future and change can help to prevent the individual from becoming overwhelmed by their history of trauma.[45] This is a risk especially with CPTSD, as multiple traumas are common within this diagnosis. Generally, care providers address a client's suicidality before moving on to other aspects of treatment. Because PTSD can make an individual more likely to experience suicidal ideation,[46] DBT can be an option to stabilize suicidality and aid in other treatment modalities.[46]

Some critics argue that while DBT can be used to treat CPTSD, it is not significantly more effective than standard PTSD treatments. Further, this argument posits that DBT decreases self-injurious behaviors (such as cutting or burning) and increases interpersonal functioning but neglects core CPTSD symptoms such as impulsivity, cognitive schemas (repetitive, negative thoughts), and emotions such as guilt and shame.[44] The ISTSS reports that CPTSD requires treatment which differs from typical PTSD treatment, using a multiphase model of recovery, rather than focusing on traumatic memories.[37] The recommended multiphase model consists of establishing safety, distress tolerance, and social relations.[37]

Because DBT has four modules which generally align with these guidelines (Mindfulness, Distress Tolerance, Affect Regulation, Interpersonal Skills) it is a treatment option. Other critiques of DBT discuss the time required for the therapy to be effective.[47] Individuals seeking DBT may not be able to commit to the individual and group sessions required, or their insurance may not cover every session.[47]

A study co-authored by Linehan found that among women receiving outpatient care for BPD and who had attempted suicide in the previous year, 56% additionally met criteria for PTSD.[48] Because of the correlation between borderline personality disorder traits and trauma, some settings began using DBT as a treatment for traumatic symptoms.[49] Some providers opt to combine DBT with other PTSD interventions, such as prolonged exposure therapy (PE) (repeated, detailed description of the trauma in a psychotherapy session) or cognitive processing therapy (CPT) (psychotherapy which addresses cognitive schemas related to traumatic memories).

For example, a regimen which combined PE and DBT would include teaching mindfulness skills and distress tolerance skills, then implementing PE. The individual with the disorder would then be taught acceptance of a trauma's occurrence and how it may continue to affect them throughout their lives.[50][49] Participants in clinical trials such as these exhibited a decrease in symptoms, and throughout the 12-week trial, no self-injurious or suicidal behaviors were reported.[50]

Another argument which supports the use of DBT as a treatment for trauma hinges upon PTSD symptoms such as emotion regulation and distress. Some PTSD treatments such as exposure therapy may not be suitable for individuals whose distress tolerance and/or emotion regulation is low.[51] Biosocial theory posits that emotion dysregulation is caused by an individual's heightened emotional sensitivity combined with environmental factors (such as invalidation of emotions, continued abuse/trauma), and tendency to ruminate (repeatedly think about a negative event and how the outcome could have been changed).[52]

An individual who has these features is likely to use maladaptive coping behaviors.[52] DBT can be appropriate in these cases because it teaches appropriate coping skills and allows the individuals to develop some degree of self-sufficiency.[52] The first three modules of DBT increase distress tolerance and emotion regulation skills in the individual, paving the way for work on symptoms such as intrusions, self-esteem deficiency, and interpersonal relations.[51]

Noteworthy is that DBT has often been modified based on the population being treated. For example, in veteran populations DBT is modified to include exposure exercises and accommodate the presence of traumatic brain injury (TBI), and insurance coverage (i.e. shortening treatment).[50][53] Populations with comorbid BPD may need to spend longer in the "Establishing Safety" phase.[44] In adolescent populations, the skills training aspect of DBT has elicited significant improvement in emotion regulation and ability to express emotion appropriately.[53] In populations with comorbid substance use, adaptations may be made on a case-by-case basis.[54]

For example, a provider may wish to incorporate elements of motivational interviewing (psychotherapy which uses empowerment to inspire behavior change). The degree of substance use should also be considered. For some individuals, substance use is the only coping behavior they know, and as such the provider may seek to implement skills training before targeting substance reduction. Inversely, a client's substance use may be interfering with attendance or other treatment compliance and the provider may choose to address the substance use before implementing DBT for the trauma.[54]

See also

[edit]- Acceptance and commitment therapy – Form of cognitive behavioral therapy

- Behaviour therapy – Clinical psychotherapy that uses techniques derived from behaviourism and/or cognitive psychology

- Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy – Mental health conditions

- Mentalization-based treatment – Form of psychotherapy

- Nonviolent Communication – Communication process intended to increase empathy

- Rational emotive behavior therapy – Psychotherapy

- Social skills – Competence facilitating interaction and communication with others

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Chapman, AL (2006). "Dialectical behavior therapy: current indications and unique elements". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 3 (9): 62–8. PMC 2963469. PMID 20975829.

- ^ "An Overview of Dialectical Behavior Therapy – Psych Central". May 17, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Linehan, M. M.; Dimeff, L. (2001). "Dialectical Behavior Therapy in a nutshell" (PDF). The California Psychologist. 34: 10–13.

- ^ a b c d Linehan, Marsha M. (2014). "Research on Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Summary of Non-rct Studies" (PDF). guilford.com (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Dimeff, LA; Linehan, MM (2008). "Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abusers". Addict Sci Clin Pract. 4 (2): 39–47. doi:10.1151/ascp084239. PMC 2797106. PMID 18497717.

- ^ "What is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)?". Behavioral Tech. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ Janowsky, David S. (1999). Psychotherapy indications and outcomes. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. pp. 100. ISBN 978-0-88048-761-0.

- ^ Brody, Jane E. (May 6, 2008). "The Growing Wave of Teenage Self-Injury". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ^ Decker, S.E.; Naugle, A.E. (2008). "DBT for Sexual Abuse Survivors: Current Status and Future Directions" (PDF). Journal of Behavior Analysis of Offender and Victim: Treatment and Prevention. 1 (4): 52–69. doi:10.1037/h0100456. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2010.

- ^ Linehan, Marsha M.; Schmidt, Henry III; Dimeff, Linda A.; Craft, J. Christopher; Kanter, Jonathan; Comtois, Katherine A. (1999). "Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Drug-Dependence". American Journal on Addictions. 8 (4): 279–292. doi:10.1080/105504999305686. PMID 10598211.

- ^ Linehan, M. M.; Armstrong, H. E.; Suarez, A.; Allmon, D.; Heard, H. L. (1991). "Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients". Archives of General Psychiatry. 48 (12): 1060–64. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. PMID 1845222.

- ^ Linehan, M. M.; Heard, H. L.; Armstrong, H. E. (1993). "Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioural treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients". Archives of General Psychiatry. 50 (12): 971–974. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240055007. PMID 8250683.

- ^ Kliem, S.; Kröger, C. & Kossfelder, J. (2010). "Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 78 (6): 936–951. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.456.8102. doi:10.1037/a0021015. PMID 21114345.

- ^ Harvey, Lauren J.; White, Fiona A.; Hunt, Caroline; Abbott, Maree (October 1, 2023). "Investigating the efficacy of a Dialectical behaviour therapy-based universal intervention on adolescent social and emotional well-being outcomes". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 169: 104408. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2023.104408. ISSN 0005-7967. PMID 37804543.

- ^ Bass, Christopher; van Nevel, Jolene; Swart, Joan (2014). "A comparison between dialectical behavior therapy, mode deactivation therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of adolescents". International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 9 (2): 4–8. doi:10.1037/h0100991.

- ^ Hofmann, Stefan G.; Sawyer, Alice T.; Fang, Angela (September 1, 2010). "The Empirical Status of the 'New Wave' of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy". Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 33 (3): 701–710. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.006. ISSN 0193-953X. PMC 2898899. PMID 20599141.

- ^ Gilbert, Kirsten; Hall, Karyn; Codd, R Trent (January 8, 2020). "Radically Open Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Social Signaling, Transdiagnostic Utility and Current Evidence". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 13: 19–28. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S201848. ISSN 1179-1578. PMC 6955577. PMID 32021506.

- ^ Clarke, Stephanie; Allerhand, Lauren A.; Berk, Michele S. (October 24, 2019). "Recent advances in understanding and managing self-harm in adolescents". F1000Research. 8: 1794. doi:10.12688/f1000research.19868.1. PMC 6816451. PMID 31681470.

- ^ Choi-Kain, Lois W.; Finch, Ellen F.; Masland, Sara R.; Jenkins, James A.; Unruh, Brandon T. (February 3, 2017). "What Works in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder". Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 4 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1007/s40473-017-0103-z. PMC 5340835. PMID 28331780.

- ^ Little, Hannah; Tickle, Anna; das Nair, Roshan (October 16, 2017). "Process and impact of dialectical behaviour therapy: A systematic review of perceptions of clients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder" (PDF). Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 91 (3): 278–301. doi:10.1111/papt.12156. PMID 29034599. S2CID 32268378.

- ^ Valentine, Sarah E.; Bankoff, Sarah M.; Poulin, Renée M.; Reidler, Esther B.; Pantalone, David W. (January 2015). "The Use of Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Training as Stand-Alone Treatment: A Systematic Review of the Treatment Outcome Literature". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 71 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1002/jclp.22114. PMID 25042066.

- ^ Zalewski, Maureen; Lewis, Jennifer K; Martin, Christina Gamache (June 2018). "Identifying novel applications of dialectical behavior therapy: considering emotion regulation and parenting". Current Opinion in Psychology. 21: 122–126. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.013. PMID 29529427. S2CID 3838955.

- ^ Lakeman, Richard; King, Peter; Hurley, John; Tranter, Richard; Leggett, Andrew; Campbell, Katrina; Herrera, Claudia (August 2022). "Towards online delivery of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy: A scoping review". International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 31 (4): 843–856. doi:10.1111/inm.12976. PMC 9305106. PMID 35048482.

- ^ "What is Mindfulness? – The Linehan Institute". linehaninstitute.org. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Ellen, Astrachan-Fletcher (2009). The dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook for bulimia using DBT to break the cycle and regain control of your life. New Harbinger Publications. ISBN 9781608822560. OCLC 955646721.

- ^ a b Pederson, Lane (2015). "19 Skills Training". Dialectical behavior therapy: a contemporary guide for practitioners. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley. ISBN 9781118957882.

- ^ a b Dietz, Lisa (2003). "DBT Skills List". Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Holmes, P.; Georgescu, S. & Liles, W. (2005). "Further delineating the applicability of acceptance and change to private responses: The example of dialectical behavior therapy" (PDF). The Behavior Analyst Today. 7 (3): 301–311.

- ^ Pederson, Lane (2012). "Interpersonal Effectiveness". The expanded dialectical behavior therapy skills training manual: practical DBT for self-help, and individual and group treatment settings. Eau Claire, WI: Premier Pub. & Media. ISBN 9781936128129.

- ^ "Dialectical Behavior Therapy Applications for People with Borderline Personality Disorder". community.counseling.org. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Pederson, Lane (2015). "13 Self-Monitoring with the Diary Card". Dialectical behavior therapy: a contemporary guide for practitioners. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley. ISBN 9781118957882.

- ^ Sampl, S.; Wakai, S.; Trestman, R. & Keeney, E.M. (2008). "Functional Analysis of Behavior in Corrections: Empowering Inmates in Skills Training Groups". Journal of Behavior Analysis of Offender and Victim: Treatment and Prevention. 1 (4): 42–51. doi:10.1037/h0100455.

- ^ "Self Awareness and Insight Through Dialectical Behavior Therapy: The Chain Analysis". parkslopetherapy.net. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Stoffers, JM; Völlm, BA; Rücker, G; Timmer, A; Huband, N; Lieb, K (August 15, 2012). "Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD005652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2. PMC 6481907. PMID 22895952.

- ^ Iskric, Adam; Barkley-Levenson, Emily (December 17, 2021). "Neural Changes in Borderline Personality Disorder After Dialectical Behavior Therapy–A Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12: 772081. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.772081. PMC 8718753. PMID 34975574.

- ^ Lynch, Thomas (January–February 2003). "Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Depressed Older Adults: A Randomized Pilot Study". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 11 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1097/00019442-200301000-00006. PMID 12527538.

- ^ a b c Heide, F. Jackie June ter; Mooren, Trudy M.; Kleber, Rolf J. (February 12, 2016). "Complex PTSD and phased treatment in refugees: a debate piece". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 7 (1): 28687. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v7.28687. ISSN 2000-8198. PMC 4756628. PMID 26886486.

- ^ Bryant, Richard A. (August 2010). "The Complexity of Complex PTSD". American Journal of Psychiatry. 167 (8): 879–881. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040606. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 20693462.

- ^ Cloitre, Marylene (February 1, 2021). "Complex PTSD: assessment and treatment". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 12 (sup1). doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1866423. ISSN 2000-8066. PMC 8018425.

- ^ a b Olson-Morrison, Debra (2017). "Integrative play therapy with adults with complex trauma: A developmentally-informed approach". International Journal of Play Therapy. 26 (3): 172–183. doi:10.1037/pla0000036. ISSN 1939-0629.

- ^ a b Maercker, Andreas; Hecker, Tobias; Augsburger, Mareike; Kliem, Sören (January 2018). "ICD-11 Prevalence Rates of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a German Nationwide Sample". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 206 (4): 270–276. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000000790. ISSN 0022-3018. PMID 29377849. S2CID 4438682.

- ^ https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases} [bare URL]

- ^ a b c Lawson, David M. (June 21, 2017). "Treating Adults With Complex Trauma: An Evidence-Based Case Study". Journal of Counseling & Development. 95 (3): 288–298. doi:10.1002/jcad.12143. ISSN 0748-9633.

- ^ a b c d Ford, Julian D; Courtois, Christine A (2014). "Complex PTSD, affect dysregulation, and borderline personality disorder". Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 1 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/2051-6673-1-9. ISSN 2051-6673. PMC 4579513. PMID 26401293.

- ^ Fasulo, Samuel J.; Ball, Joanna M.; Jurkovic, Gregory J.; Miller, Alec L. (April 2015). "Towards the Development of an Effective Working Alliance: The Application of DBT Validation and Stylistic Strategies in the Adaptation of a Manualized Complex Trauma Group Treatment Program for Adolescents in Long-Term Detention". American Journal of Psychotherapy. 69 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.219. ISSN 0002-9564. PMID 26160624.

- ^ a b Krysinska, Karolina; Lester, David (January 29, 2010). "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Suicide Risk: A Systematic Review". Archives of Suicide Research. 14 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/13811110903478997. ISSN 1381-1118. PMID 20112140. S2CID 10827703.

- ^ a b Landes, Sara J.; Garovoy, Natara D.; Burkman, Kristine M. (March 25, 2013). "Treating Complex Trauma Among Veterans: Three Stage-Based Treatment Models". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 69 (5): 523–533. doi:10.1002/jclp.21988. ISSN 0021-9762. PMID 23529776.

- ^ Harned, Melanie S.; Rizvi, Shireen L.; Linehan, Marsha M. (October 2010). "Impact of Co-Occurring Posttraumatic Stress Disorder on Suicidal Women With Borderline Personality Disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry. 167 (10): 1210–1217. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081213. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 20810470.

- ^ a b Steil, Regina; Dittmann, Clara; Müller-Engelmann, Meike; Dyer, Anne; Maasch, Anne-Marie; Priebe, Kathlen (January 2018). "Dialectical behaviour therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse: a pilot study in an outpatient treatment setting". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 9 (1): 1423832. doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1423832. ISSN 2000-8198. PMC 5774406. PMID 29372016.

- ^ a b c Meyers, Laura; Voller, Emily K.; McCallum, Ethan B.; Thuras, Paul; Shallcross, Sandra; Velasquez, Tina; Meis, Laura (March 22, 2017). "Treating Veterans With PTSD and Borderline Personality Symptoms in a 12-Week Intensive Outpatient Setting: Findings From a Pilot Program". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 30 (2): 178–181. doi:10.1002/jts.22174. ISSN 0894-9867. PMID 28329406.

- ^ a b Wagner, Amy W.; Rizvi, Shireen L.; Harned, Melanie S. (2007). "Applications of dialectical behavior therapy to the treatment of complex trauma-related problems: When one case formulation does not fit all". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 20 (4): 391–400. doi:10.1002/jts.20268. ISSN 0894-9867. PMID 17721961.

- ^ a b c Florez, Ivonne Andrea; Bethay, J. Scott (January 13, 2017). "Using Adapted Dialectical Behavioral Therapy to Treat Challenging Behaviors, Emotional Dysregulation, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder in an Individual With Mild Intellectual Disability". Clinical Case Studies. 16 (3): 200–215. doi:10.1177/1534650116687073. ISSN 1534-6501. S2CID 151755852.

- ^ a b Denckla, Christy A.; Bailey, Robert; Jackson, Christie; Tatarakis, John; Chen, Cory K. (November 2015). "A Novel Adaptation of Distress Tolerance Skills Training Among Military Veterans: Outcomes in Suicide-Related Events". Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 22 (4): 450–457. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.04.001. ISSN 1077-7229.

- ^ a b Litt, Lisa (March 26, 2013). "Clinical Decision Making in the Treatment of Complex PTSD and Substance Misuse". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 69 (5): 534–542. doi:10.1002/jclp.21989. ISSN 0021-9762. PMID 23533007.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Koons, Cedar R; Robins, Clive J; Tweed, J.Lindsey; Lynch, Thomas R; Gonzalez, Alicia M; Morse, Jennifer Q; Bishop, G.Kay; Butterfield, Marian I; Bastian, Lori A (2001). "Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder". Behavior Therapy. 32 (2): 371–390. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.1646. doi:10.1016/s0005-7894(01)80009-5.

- Linehan, M.M.; Comtois, K.A.; Murray, A.M.; Brown, M.Z.; Gallop, R.J.; Heard, H.L.; Korslund, K.E.; Tutek, D.A.; Reynolds, S.K.; Lindenboim, N. (2006). "Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 63 (7): 757–66. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. PMID 16818865.

- Linehan, M.M.; Dimeff, L.A.; Reynolds, S.K.; Comtois, K.A.; Welch, S.S.; Heagerty, P.; Kivlahan, D.R. (2002). "Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 67 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00011-x. PMID 12062776.

- Linehan, M.M.; Heard, H.L. (1993). "'Impact of treatment accessibility on clinical course of parasuicidal patients': Reply". Archives of General Psychiatry. 50 (2): 157–158. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140083011.

- Linehan, M.M.; Schmidt, H.; Dimeff, L.A.; Craft, J.C.; Kanter, J.; Comtois, K.A. (1999). "Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence". American Journal on Addictions. 8 (4): 279–292. doi:10.1080/105504999305686. PMID 10598211.

- Linehan, M.M.; Tutek, D.A.; Heard, H.L.; Armstrong, H.E. (1994). "Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients". American Journal of Psychiatry. 151 (12): 1771–1776. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.12.1771. PMID 7977884.

- Lopez, Amy; Chessick, Cheryl A. (2013). "DBT Graduate Group Pilot Study: A Model to Generalize Skills to Create a "Life Worth Living"". Social Work in Mental Health. 11 (2): 141–153. doi:10.1080/15332985.2012.755145. S2CID 143376433.

- van den Bosch, L.M.C.; Verheul, R.; Schippers, G.M.; van den Brink, W. (2002). "Dialectical Behavior Therapy of borderline patients with and without substance use problems: Implementation and long-term effects". Addictive Behaviors. 27 (6): 911–923. doi:10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00293-9. PMID 12369475.

- Verheul, R.; van den Bosch, L.M.C.; Koeter, M.W.J.; de Ridder, M.A.J.; Stijnen, T.; van den Brink, W. (2003). "Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in the Netherlands". British Journal of Psychiatry. 182 (2): 135–140. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. PMID 12562741.

Further reading

[edit]- Chapman, A. L. (2006). "Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Current Indications and Unique Elements". Psychiatry. 3 (9): 62–68. PMC 2963469. PMID 20975829.

- Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder by Marsha M. Linehan. 1993. ISBN 0-89862-183-6.

- DBT For Dummies by Gillian Galen PsyD, Blaise Aguirre MD. ISBN 978-1-119-73012-5.

- Depressed and Anxious: The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Workbook for Overcoming Depression & Anxiety by Thomas Marra. ISBN 978-1-57224-363-7.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Suicidal Adolescents by Alec L. Miller, Jill H. Rathus, and Marsha M. Linehan. Foreword by Charles R. Swenson. ISBN 978-1-59385-383-9.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy Workbook: Practical DBT Exercises for Learning Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation, & Distress Tolerance (New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook) by Matthew McKay, Jeffrey C. Wood, and Jeffrey Brantley. ISBN 978-1-57224-513-6.

- Don't Let Your Emotions Run Your Life: How Dialectical Behavior Therapy Can Put You in Control (New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook) by Scott E. Spradlin. ISBN 978-1-57224-309-5.

- Fatal Flaws: Navigating Destructive Relationships with People with Disorders of Personality and Character by Stuart C. Yudovsky. ISBN 1-58562-214-1.

- Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder by Marsha M. Linehan. 1993. ISBN 0-89862-034-1.

- The High Conflict Couple: A Dialectical Behavior Therapy Guide to Finding Peace, Intimacy, & Validation by Alan E. Fruzzetti. ISBN 1-57224-450-X.

- The Miracle of Mindfulness by Thích Nhất Hạnh. ISBN 0-8070-1239-4.