Right to food

The right to food, and its variations, is a human right protecting the right of people to feed themselves in dignity, implying that sufficient food is available, that people have the means to access it, and that it adequately meets the individual's dietary needs. The right to food protects the right of all human beings to be free from hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition.[4] The right to food implies that governments only have an obligation to hand out enough free food to starving recipients to ensure subsistence, it does not imply a universal right to be fed. Also, if people are deprived of access to food for reasons beyond their control, for example, because they are in detention, in times of war or after natural disasters, the right requires the government to provide food directly.[5]

The right is derived from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[5] which has 170 state parties as of April 2020.[2] States that sign the covenant agree to take steps to the maximum of their available resources to achieve progressively the full realization of the right to adequate food, both nationally and internationally.[6][4] In a total of 106 countries the right to food is applicable either via constitutional arrangements of various forms or via direct applicability in law of various international treaties in which the right to food is protected.[7]

At the 1996 World Food Summit, governments reaffirmed the right to food and committed themselves to halve the number of hungry and malnourished from 840 to 420 million by 2015. However, the number has increased over the past years, reaching an infamous record in 2009 of more than 1 billion undernourished people worldwide.[4] Furthermore, the number who suffer from hidden hunger – micronutrient deficiences that may cause stunted bodily and intellectual growth in children – amounts to over 2 billion people worldwide.[8]

Whilst under international law, states are obliged to respect, protect and fulfill the right to food, the practical difficulties in achieving this human right are demonstrated by prevalent food insecurity across the world, and ongoing litigation in countries such as India.[9][10] In the continents with the biggest food-related problems – Africa, Asia and South America – not only is there shortage of food and lack of infrastructure but also maldistribution and inadequate access to food.[11]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[12] measures the right to food for countries around the world, based on their level of income.[13]

Definition

[edit]| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognizes the "right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food", as well as the "fundamental right to be free from hunger". The relationship between the two concepts is not straightforward. For example, "freedom from hunger" (which General Comment 12 designates as more pressing and immediate[14]) could be measured by the number of people suffering from malnutrition and at the extreme, dying of starvation. The "right to adequate food" is a much higher standard, including not only absence of malnutrition, but to the full range of qualities associated with food, including safety, variety and dignity, in short all those elements needed to enable an active and healthy life.

Inspired by the above definition, the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food in 2002 defined it as follows:[15]

The right to have regular, permanent and unrestricted access, either directly or by means of financial purchases, to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people to which the consumer belongs, and which ensure a physical and mental, individual and collective, fulfilling and dignified life free of fear.

This definition entails all normative elements explained in detail in the General Comment 12 of the ICESCR, which states:[16][note 1]

the right to adequate food is realized when every man, woman and child, alone or in community with others, have the physical and economic access at all times to adequate food or means for its procurement.

Dimensions

[edit]The former Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Ziegler, defined three dimensions to the right to food.[4][14]

- Availability refers to the possibilities either for feeding oneself directly from productive land or other natural resources, or for well functioning distribution, processing and market systems that can move food from the site of production to where it is needed in accordance with demand.

- Accessibility implies that economic and physical access to food is to be guaranteed. On the one hand, economic access means that food should be affordable for an adequate diet without compromising other basic needs. On the other hand, physically vulnerable, such as sick, children, disabled or elderly should also have access to food.

- Adequacy implies that the food must satisfy the dietary needs of every individual, taking into account age, living conditions, health, occupation, sex, culture and religion, for example. The food must be safe and adequate protective measures by both public and private means must be taken to prevent contamination of foodstuffs through adulteration and/or through bad environmental hygiene or inappropriate handling at different stages throughout the food chain; care must also be taken to identify and avoid or destroy naturally occurring toxins.

Furthermore, any discrimination in access to food, as well as to means and entitlements for its procurement, on the grounds of race, colour, sex, language, age, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status constitutes a violation of the right to food.

Agreed-upon food standards

[edit]Regarding the right to food, the international community also specified commonly agreed on standards, such as in the 1974 World Food Conference, the 1974 International Undertaking on World Food Security, the 1977 Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, the 1986 Declaration on the Right to Development, the ECOSOC Resolution 1987/90, the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, and the 1996 Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements.[17]

History

[edit]Negative or positive right

[edit]There is a traditional distinction between two types of human rights. On the one hand, negative or abstract rights that are respected by non-intervention. On the other hand, positive or concrete rights that require resources for its realisation. However, it is nowadays contested whether it is possible to clearly distinguish between these two types of rights.[18]

The right to food can accordingly be divided into the negative right to obtain food by one's own actions, and the positive right to be supplied with food if one is unable to access it. The negative right to food was recognised as early as in England's 1215 Magna Carta which reads that: "no one shall be 'amerced' (fined) to the extent that they are deprived of their means of living."[18]

International developments from 1941 onwards

[edit]This section provides an overview of international developments relevant to the establishment and implementation of the right to food from the mid-20th century onwards.[19]

- 1941 – In his Four Freedoms speech, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt includes as one of the freedoms:[20]

Later this freedom formed part of the 1945 United Nations Charter (Article 1(3)).[20]"The freedom from want."

- 1948 – Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the right to food as part of the right to an adequate standard of living:

"Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control" (Article 25).

- 1966 – The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, reiterates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with regard to the right to an adequate standard of living and, in addition, specifically recognises the right to be free from hunger. The covenant, states parties recognise:

"the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food" (Article 11.1) and "the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger." (Article 11.2).

- 1976 – Entry into force of the Covenant.

- 1987 – Establishment of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights overseeing the implementation of the Covenant and beginning a more legal interpretation of the Covenant.

- 1999 – The Committee adopts General Comment No. 12 'The Right to Adequate Food', describing the various State obligations derived from the Covenant regarding the right to food.[14]

- 2009 – Adoption of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, making the right to food justiciable at the international level.

- 1974 – Adoption of the Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition at the World Food Conference.[21]

- 1988 – Adoption of the right to food in the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the area of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (the "Protocol of San Salvador").

- 1996 – The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) organises the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome, resulting in the Rome Declaration on World Food Security.[21]

- 2004 – The FAO adopts the Right to Food Guidelines, offering guidance to States on how to implement their obligations on the right to food. The drafting of the guidelines was initiated as a result of the 2002 World Food Summit.[5]

- 2000 – The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food is established.[22]

- 2000 – Adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, including Goal 1: to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger by 2015.

- 2012 – The Food Assistance Convention is adopted as a result of the Food Aid Convention (1985?), making it the first legally binding international treaty on food aid.

Amartya Sen won his 1998 Nobel Prize in part for his work in demonstrating that famine and mass starvation in modern times was not typically the product of a lack of food; rather, it usually arose from problems in food distribution networks or from government policies.[23]

Legal status

[edit]The right to food is protected under international human rights and humanitarian law.[5][24] Within the U.N.'s human rights system, it has been presented consistently as a basic human right.[25]: 139

International law

[edit]The right to food is recognized in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25) as part of the right to an adequate standard of living, and is enshrined in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Article 11).[5] The 2009 Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights makes the right to food justiciable at the international level.[19] In 2012, the Food Assistance Convention was adopted, making it the first legally binding international treaty on food aid.

International instruments

[edit]It is also recognized in many specific international instruments as varied as the 1948 Genocide Convention (Article 2), the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (Articles 20 and 23),[26] the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (Articles 24(2)(c) and 27(3)), the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (Articles 12(2)), or the 2007 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Articles 25(f) and 28(1)).[5]

Regional instruments

[edit]The right to food is also recognized in regional instruments, such as:

- the 1988 Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the area of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights or "Protocol of San Salvador" (Article 12);

- the 1990 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child;

- the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, implicitly in the right to life (Article 4), right to health (Article 14), and right to economic, social and cultural development (Article 22), according to the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights decision in SERAC v Nigeria;[27]

- the 2003 Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa or "Maputo Protocol" (Article 15);

- the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (Article 28).

- neither the European Convention on Human Rights nor the European Social Charter mentions a right to food.

There are also such instruments in many national constitutions.[5]

Non-legally binding instruments

[edit]There are several non-legally binding international human rights instruments relevant to the right to food. They include recommendations, guidelines, resolutions or declarations. The most detailed is the 2004 Right to Food Guidelines. They are a practical tool to help implement the right to adequate food.[5] The Right to Food Guidelines are not legally binding but draw upon international law and are a set of recommendations States have chosen on how to implement their obligations under Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[5] Finally, the preamble to the 1945 Constitution of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization provides that:[26]

the Nations accepting this Constitution, being determined to promote the common welfare by furthering separate and collective action on their part for the purpose of: raising levels of nutrition and standards of living ... and thus ... ensuring humanity's freedom from hunger....

Other documents

[edit]In 1993, the International Food Security Treaty wa developed in the US and Canada.[28]

In 1998, a Conference on Consensus Strategy on the Right To Food was held in Santa Barbara, California, US with anti-hunger experts from five continents.[29]

In 2010, a group of national and international organisations created a proposal to replace the European Union Common Agricultural Policy, which was due for change in 2013. The first article of The New Common Food and Agriculture Policy "considers food as a universal human right, not merely a commodity."[30]

State obligations

[edit]State obligations related to the right to food are well-established under international law.[5] By signing the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) states agreed to take steps to the maximum of their available resources to achieve progressively the full realization of the right to adequate food. They also acknowledge the essential role of international cooperation and assistance in this context.[31] This obligation was reaffirmed by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR).[14] Signatories to the Right to Food Guidelines also committed to implementing the right to food at a national level.

In General Comment no. 12, the CESCR interpreted the states' obligation as being of three types: the obligation to respect, protect and to fulfil:[32]

- Respect implies that states must never arbitrarily prevent people from having access to food.

- Protect means that states should take measures to ensure that enterprises or individuals do not deprive individuals of their access to adequate food.

- Fulfil (facilitate and provide) entails that governments must pro-actively engage in activities intended to strengthen people's access to and utilization of resources and means to ensure their livelihood, including food security. If, for reasons beyond their control such as at times of war or after a natural disaster, groups or individuals are unable to enjoy their right to food, then states have the obligation to provide that right directly.[4]

These were again endorsed by states, when the FAO Council adopted the Right to Food Guidelines.[4]

The ICESCR recognises that the right to freedom from hunger requires international cooperation, and relates to matters of production, the agriculture and global supply. Article 11 states that:

The States Parties to the present Covenant... shall take, individually and through international co-operation, the measures, including specific programmes, which are needed: (a) To improve methods of production, conservation and distribution of food by making full use of technical and scientific knowledge, by disseminating knowledge of the principles of nutrition and by developing or reforming agrarian systems in such a way as to achieve the most efficient development and utilization of natural resources; (b) Taking into account the problems of both food-importing and food-exporting countries, to ensure an equitable distribution of world food supplies in relation to need.

The implementation of the right to food standards at national level has consequences for national constitutions, laws, courts, institutions, policies and programmes, and for various food security topics, such as fishing, land, focus on vulnerable groups, and access to resources.[5]

National strategies on the progressive realization of the right to food should fulfill four functions:

- define the obligations corresponding to the right to adequate food, whether these are the obligations of government or those of private actors;

- improve the coordination between the different branches of government whose activities and programs may affect the realization of the right to food;

- set targets, ideally associated with measurable indicators, defining the timeframe within which particular objectives should be achieved;

- provide for a mechanism ensuring that the effect of new legislative initiatives or policies on the right[clarification needed].[5]

- International

The right to food imposes on all States obligations not only towards the persons living on their national territory, but also towards the populations of other States. The right to food is only realised when both national and international obligations are complied with. On the one hand, is the effect of the international environment and, in particular, climate change, malnutrition and food insecurity. On the other hand, the international community can only contribute if legal frameworks and institutions are established at the national level.[5]

- Non-discrimination

Under article 2(2) of the ICESCR, governments agreed that the right to food will be exercised without discrimination on grounds of sex, colour, race, age, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.[4] The CESCR stresses the special attention that should be given to disadvantaged and marginalized farmers, including women farmers, in a rural context.[33]

Adoption around the world

[edit]Framework law

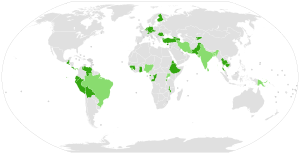

[edit]

A framework law is a "legislative technique used to address cross-sectoral issues."[34] Framework laws are more specific than a constitutional provision, as it lays down general obligations and principles. However, competent authorities and further legislation which still have to determine specific measures should be taken.[35] The adoption of framework laws was recommended by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as a "major instrument in the implementation of the national strategy concerning the right to food".[36] There are ten countries that have adopted and nine countries that are developing framework laws on food security or the right to food. This development is likely to increase in the coming years.[7] Often they are known as food security laws instead of right to food laws, but their effect is usually similar.[35]

Advantages of framework law includes that the content and scope of the right can be further specified, state and private actor obligations can be spelled out in detail, appropriate institutional mechanisms can be established, and rights to remedies can be provided for. Further advantages of framework laws include: strengthening government accountability, monitoring, helping government officials understand their role, improving access to courts and by providing administrative recourse mechanisms.[35]

However, provisions for obligations and remedies in existing framework law is not always very thorough, and it is neither always clear what they add to the justiciability of the right to food.[35]

As of 2011, the following ten countries have adopted a framework law on food security or the right to food: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Indonesia, Nicaragua, Peru and Venezuela.[35] Moreover, in 2011 the following nine countries were drafting a framework law on food security or the right to food: Honduras, India, Malawi, Mexico, Mozambique, Paraguay, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda.[35] Finally, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Peru are drafting to update, replace or strengthen their framework law.[35]

Constitutional

[edit]

There are various ways in which constitutions can take the right to food or some aspect of it into account.[37] As of 2011, 56 constitutions protect the right to food in some form or another.[7] The three main categories of constitutional recognition are: as an explicit right, as implied in broader human rights or as part of a directive principle. In addition to those, the right can also indirectly be recognised when other human rights are interpreted by a judiciary.[37]

Explicit as a right

[edit]Firstly, the right to food is explicitly and directly recognised as a right in itself or as part of a broader human right in 23 countries.[38] Three different forms can be distinguished.

1. The following nine countries recognise the right to food as a separate and stand-alone right: Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Guyana, Haiti, Kenya, South Africa, in the Interim Constitution of Nepal (as food sovereignty) and Nicaragua (as freedom from hunger).[39]

2. For a specific segment of the population the right to food is recognised in ten countries. Provisions regarding the right to food of children are present in the constitutions of: Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, and South Africa. The right to food of indigenous children is protected in the constitution of Costa Rica. Finally, the right to food of detainees and prisoners is additionally recognised in the constitution of South Africa.[39]

3. Five countries recognize the right to food explicitly as part of a human right to an adequate standard of living, quality of life, or development: Belarus, the Congo, Malawi, Moldova and Ukraine, and two recognise it as part of the right to work: Brazil and Suriname.[39] The XX. article of the Fundamental Law of Hungary recognizes the right to food as a part of a human right to health.[40]

Implicit or as directive principle

[edit]Secondly, the following 31 countries implicitly recognise the right to food in broader human rights:[37] Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bolivia, Burundi, Cambodia, Czech Rep., Congo, Costa Rica, Cyprus, Ecuador, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, Netherlands, Pakistan, Peru, Romania, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, Venezuela.[41]

Thirdly, the following thirteen countries explicitly recognise the right to food within the constitution as a directive principle or goal:[37] Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Iran, Malawi, Nigeria, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Uganda.[41]

Applicable via international law

[edit]

In some countries international treaties have a higher status than or equal status to national legislation. Consequently, the right to food may be directly applicable via international treaties if such country is member to a treaty in which the right is recognised. Such treaties include the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Excluding countries in which the right to food is implicitly or explicitly recognised in their constitution, the right is directly applicable in at least 51 additional countries via international treaties.[42]

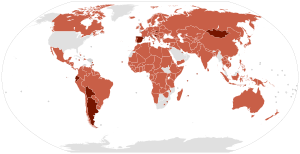

Commitment via ICESCR

[edit]- ICESCR

Parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights have to do everything to guarantee adequate nutrition, including legislating to that effect. The Covenant has become part of national legislation in over 77 countries. In these countries the provision for the right to food in the Covenant can be cited in a court. This has happened in Argentina (in the case of the right to health).[43]

However, citizens usually cannot prosecute using the Covenant, but can only do so under national law. If a country does not pass such laws a citizen has no redress, even though the state violated the covenant. The implementation of the Covenant is monitored through the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[44] In total, 160 countries have ratified the Covenant. A further 32 countries have not ratified the covenant, although 7 of them did sign it.[2]

- Optional protocol

By signing the Optional Protocol to the ICESCR, states recognise the competence of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to receive and consider[45] complaints from individuals or groups who claim their rights under the Covenant have been violated.[46] However, complainants must have exhausted all domestic remedies.[47] The committee can "examine",[48] works towards "friendly settlement",[49] in the case of grave or systematic violations of the Covenant, it can "invite that State Party to cooperate" and, finally, could "include a summary account of the results of the proceedings in its annual report".[50] The following seven countries have ratified the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mongolia, Slovakia, and Spain. A further 32 countries have signed the optional protocol.[3]

Mechanisms to achieve the right to food

[edit]The Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, De Schutter, urged the establishment in law of the right to food, so that it can be translated into national strategies and institutions. Furthermore, he recommended emerging economies to protect the rights of land users, in particular of minority and vulnerable groups. He also advised to support smallholder agriculture in the face of mega-development projects, and to stop soil and water degradation through massive shifts to agroecological practices. Finally, the UN expert suggested adopting a strategy to tackle rising obesity.[51]

The United Nations' Article 11 on the Right to Adequate Food suggests several implementation mechanisms.[14] The Article acknowledges that the most appropriate ways and means of implementing the right to adequate food will inevitably vary significantly from one State to another. Every State must choose its own approaches, but the Covenant clearly requires that each State party take whatever steps are necessary to ensure that everyone is free from hunger and as soon as possible can enjoy the right to adequate food.

The Article emphasizes that the right to food requires full compliance with the principles of accountability, transparency, people's participation, decentralization, legislative capacity and the independence of the judiciary. In terms of strategy to implement the right to food, the Article asks that the States should identify and address critical issues in regard to all aspects of the food system, including the food production and processing, food storage, retail distribution, marketing and its consumption. The implementation strategy should give particular attention to the need to prevent discrimination in access to food shops and retail network, or alternatively to resources for growing food. As part of their obligations to protect people's resource base for food, States should take appropriate steps to ensure that activities of the private business sector and civil society are in conformity with the right to food.

The Article notes that whenever a State faces severe resource constraints, whether caused by a process of economic adjustment, economic recession, climatic conditions or other factors, measures should be undertaken to ensure that the right to adequate food is especially fulfilled for vulnerable population groups and individuals.[14]

Interrelation to other rights

[edit]The idea of the interdependence and indivisibility of all human rights was a founding principle of the United Nations. This was recognised in the 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action which reads "all human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated." The right to food is considered interlinked with the following human rights in particular: right to life, right to livelihood, right to health, right to property, freedom of expression, freedom of information, right to education, freedom of association, and the right to water.[52] Other relevant rights include: the right to work, the right to social security, the right to social welfare,[53] and the right to an adequate standard of living.

For example, according to the Committee overseeing the implementation of the ICESCR, "the right to water is a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights." The need to have adequate water in order to have adequate food is in particular evident in the case of peasant farmers. Access to sustainable water resources for agriculture needs to be ensured to realise the right to food.[54] This applies even more strongly to subsistence agriculture.

See also

[edit]- Right to food by country

- Food bank

- Food politics

- Food security

- Food rescue

- Food sovereignty

- Food systems

- Famine

- Global Hunger Index

- Hunger strike

- List of people who died of starvation

- Soup kitchen

- Starvation

- World Food Programme

- Famine scales

- Global governance

- International Fund for Agricultural Development

- Regional policy

- Starvation response

- Land rights

- Seeds

- Nutrition

- Agroecology

Notes

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ General Comments are not legally binding but are authoritative interpretation of the ICESCR, which is legally binding upon the States Parties to this treaty.

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e Knuth 2011.

- ^ a b c d United Nations Treaty Collection 2012a

- ^ a b c United Nations Treaty Collection 2012b

- ^ a b c d e f g Ziegler 2012: "What is the right to food?"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food 2012a: "Right to Food."

- ^ International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966: article 2(1), 11(1) and 23.

- ^ a b c Knuth 2011: 32.

- ^ Ahluwalia 2004: 12.

- ^ Westcott, Catherine and Nadia Khoury and CMS Cameron McKenna,The Right to Food, (Advocates for International Development, October 2011)http://a4id.org/sites/default/files/user/Right%20to%20Food%20Legal%20Guide.pdf.

- ^ "Aadhaar vs. Right to food".

- ^ Ahluwalia 2004: iii.

- ^ "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ "Right to food - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ a b c d e f Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1999.

- ^ Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food 2008: para. 17; quoted in Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food 2012a.

- ^ Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1999: para. 6.

- ^ Ahluwalia 2004: footnote 23.

- ^ a b Food and Agriculture Organization 2002: "The road from Magna Carta."

- ^ a b Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food 2010a: 4.

- ^ a b Ahluwalia 2004: 10.

- ^ a b Food and Agriculture Organization 2012b.

- ^ Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food 2012a: "Mandate."

- ^ Steele, Jonathan (19 April 2001). "The Guardian Profile: Amartya Sen". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Ahluwalia 2004: 10-12.

- ^ Shi, Song (2023). China and the Internet: Using New Media for Development and Social Change. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9781978834736.

- ^ a b Ahluwalia 2004: 11.

- ^ African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights: para. 64-66 (p. 26).

- ^ The International Food Security Treaty Association 2012

- ^ The International Food Security Treaty Association 2012: "About the IFST."

- ^ Proposal for a New European Agriculture and Food policy that meets the challenges of this century 2010.

- ^ International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966: article 2(1), 11(1) and 23; Ziegler 2012: "What is the right to food?"

- ^ Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1999

- ^ Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1999: para. 7.

- ^ Knuth 2011: 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Knuth 2011: 30-1.

- ^ Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1999: para. 29; cited in

- ^ a b c d Knuth 2011: 14.

- ^ Knuth 2011: 14; 36.

- ^ a b c Knuth 2011: 21.

- ^ https://jak.ppke.hu/uploads/articles/12332/file/Kovacs_Julcsi_tezisak.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Knuth 2011: 35-6.

- ^ Knuth 2011: 23, 32.

- ^ Golay 2006: 21; see also Golay 2006: 27-8.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization 2002;Ahluwalia 2004: 20.

- ^ Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2008: Article 1.

- ^ Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2008: Article 2.

- ^ Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2008: Article 3.

- ^ Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2008: Article 8.

- ^ Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2008: Article 7.

- ^ Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2008: Article 11.

- ^ De Schutter 2012, para. 3.

- ^ Ahluwalia 2004: 14.

- ^ Golay 2006: 13.

- ^ Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2002: para. 1.

References

[edit]- African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, ACHPR decision in case SERAC v. Nigeria, archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- Ahluwalia, Pooja (2004), "The Implementation of the Right to Food at the National Level: A Critical Examination of the Indian Campaign on the Right to Food as an Effective Operationalization of Article 11 of ICESCR" (PDF), Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice Working Paper No. 8, 2004., New York: NYU School of Law, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1999), General Comment No. 12: The right to adequate food (Art. 11) (E/C.12/1999/5), United Nations, archived from the original on 5 June 2012.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2002), General Comment No. 15: The right to water (Arts. 11 and 12) (E/C.12/2002/11), United Nations, archived from the original on 2 June 2012.

- Commission on Human Rights (17 April 2000), Res. 2000/10, United Nations.

- De Schutter, Olivier (2012), 'Unfinished progress' – UN expert examines food systems in emerging countries (PDF), Geneva: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2018.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2002), "What is the right to food?", World Food Summit: five years later, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, archived from the original on 14 May 2012.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2012a), Constitutional Protection of the right to food, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, retrieved 21 May 2012.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2012b), Right to Food Timeline, Legal Office, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, archived from the original on 13 January 2012.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2012c), Right to Food Knowledge Centre, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, archived from the original on 4 June 2012.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2012d), Background to the Voluntary Guidelines, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, archived from the original on 23 November 2012.

- Golay, C. (2006), "The Right to Food: A fundamental human right affirmed by the United Nations and recognized in regional treaties and numerous national constitutions" (PDF), Part of a series of the Human Rights Programme of the Europe-Third World Centre (CETIM), M. Özden, Europe-Third World Centre (CETIM), archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2013.

- Human Rights Council (2007), Mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food. (Resolution A/HRC/6/L.5/Rev.1), Human Rights Council.

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, United Nations, 1966.

- The International Food Security Treaty Association (2012), International Food Security Treaty, retrieved 21 May 2012.

- Knuth, Lidija (2011), Constitutional and Legal Protection of the Right to Food around the World, Margret Vidar, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2012.

- "Proposal for a New European Agriculture and Food policy that meets the challenges of this century" (PDF), INRA Dijon, 12 July 2010, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-13.

- Right to Food Campaign (2012), A Brief Introduction to the Campaign, archived from the original on 5 February 2012.

- Locke, John (1689), Two Treatises of Government, vol. 2.

- Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (PDF), United Nations, 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-16.

- Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food (2008), Promotion and Protection of All Human Rights, Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Including the Right to Development, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Jean Ziegler (A/HRC/7/5) (PDF), Human Rights Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2012.

- Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food (2010a), Countries tackling hunger with a right to food approach. Significant progress in implementing the right to food at national scale in Africa, Latin America and South Asia. Briefing Note 01. (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2018.

- Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food (2012a), Website of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Olivier De Schutter, retrieved 24 May 2012.

- United Nations Treaty Collection (2012a), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, United Nations, archived from the original on 11 June 2012.

- United Nations Treaty Collection (2012b), Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, United Nations, archived from the original on 18 July 2012.

- Ziegler, Jean (2012), Right to Food. Website of the former Special Rapporteur, archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

External links

[edit]- United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food

- International Food Security Treaty Association

- Website former UN Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Ziegler

- UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the Right to Food

- Right to Food on Humanium.

- The Right to Food, Global and Local: A Panel Discussion, November 12, 2013. Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. Accessed 2020-01-12.